Abstract

Levonorgestrel intrauterine-releasing system (LNG-IUS), an intrauterine device, is recommended for patients with adenomyosis; however, it often shows poor outcomes in these patients because of their large uterine size. This prospective study evaluated the feasibility, short-term therapeutic effectiveness and safety of hysteroscopic suture fixation to secure the LNG-IUS in patients with adenomyosis. Forty-seven patients diagnosed with adenomyosis underwent hysteroscopic LNG-IUS suture fixation between October 2022 and January 2024, with postoperative follow-up for assessing IUD expulsion, treatment outcomes, and adverse events. Postoperative follow-up was conducted for all patients for at least 1 year. In one patient, LNG-IUS expulsion occurred at 3 months post-procedure, while in 2 patients, device displacement was detected through transvaginal sonography. Median visual analog scale scores and pictorial blood loss assessment chart scores for dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), respectively, were significantly decreased post-insertion. Irregular uterine bleeding emerged as the most frequent adverse event (42.6%). Two patients discontinued the therapy due to persistent dysmenorrhea or HMB. This pilot study demonstrates the technical feasibility and preliminary efficacy of hysteroscopic LNG-IUS suture fixation, with the lower short-term risk of device expulsion supporting further comparative trials. The absence of a control group is the primary limitation, necessitating cautious interpretation of outcomes as preliminary. Standardizing patient selection criteria and a comparative study with larger trials and longer-term follow-up (up to 5 years) is needed to confirm the superiority of this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a benign gynecological condition characterized by the ectopic presence of stroma and endometrial glands within the myometrium1; it has a prevalence rate of 20.9–34% in reproductive-aged women2,3. While asymptomatic cases are often incidentally diagnosed during post-hysterectomy histopathological evaluation4, symptomatic presentations typically include abnormal uterine bleeding, secondary dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia (potentially inducing severe anemia), and infertility, which substantially compromise the quality of life of women. Currently, the pathogenetic mechanisms of adenomyosis are unclear5,6,7,8. One of the more recent theories is that genetic and epigenetic changes affect intracellular aromatase activity, leading to intracellular production of estrogen and formation of an inflammatory fibrotic endometrioid tissue exterior to the endometrium9. Though hysterectomy is the sole effective treatment option according to the recent researches, but the latest clinical guidelines still indicate that medical treatment remains the first-line treatment for uterine adenomyosis10,11,12. Commonly used medications included combined oral contraceptives (COCs), progesterone pills, dienogest, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), levonorgestrel intrauterine-releasing system (LNG-IUS), danazol and non-hormonal medications can be utilized to alleviate the symptoms of adenomyosis and control its progression10,13. The LNG-IUS is among the most extensively researched therapeutic interventions for symptomatic adenomyosis. The LNG-IUS is a highly safe and effective reversible contraceptive with long-acting efficacy up to 5 years. LNG-IUS can treat chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and excessive menstruation in adenomyosis patients for up to five years. Dienogest and LNG-IUS both have considerable efficacy in alleviating the pain levels of patients with uterine adenomyosis and improving their quality of life. However, LNG-IUS is more effective in reducing the menstrual flow of patients14. LNG-IUS was found to be more effective than COCs in alleviating symptoms of ademomyosis15. However, because of the large uterine size of patients with adenomyosis, the high expulsion rate after LNG-IUS placement has affected patients’ satisfaction16. In 2021, Professor Tong introduced hysteroscopic suture fixation of LNG-IUS in patients with adenomyosis to prevent expulsion risk17. Since 2022, our department gradually began to adopt this approach in clinical practice. In the present study, we evaluated postoperative outcomes (device expulsion/displacement, treatment outcomes, and adverse events) in 47 consecutive patients who underwent this procedure up to January 1, 2024.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study recruited women patients diagnosed to have adenomyosis who received hysteroscopic LNG-IUS suture fixation between October 2022 and January 2024. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) premenopausal women aged between 25 and 50 years old; (2) diagnosis of adenomyosis confirmed through transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS); and (3) strong desire for uterine preservation. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) inconclusive TVUS-based diagnosis of adenomyosis; (2) pregnancy or lactation; (3) endometrial atypical hyperplasia or malignancy on biopsy; (4) the depth of the uterine cavity exceeds 12 cm; (5) received GnRHa treatment within 4 weeks prior to the surgery; (6) contraindications to LNG-IUS placement; (7) Using anticoagulant drugs (such as warfarin, aspirin, etc.) before the operation, or (8) contraindications to hysteroscopic surgery. As this is a single-center study aiming to assess feasibility and generate preliminary data for future study, the sample size was based on pragmatic constraints and pilot study recommendations18,19. Patient follow-up was continued through December 2024.

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Second Hospital of Shandong University (Approval Number: KYLL-2022P301; Approval Date: September 29th, 2022). It was performed by strictly following the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). All patients provided their written informed consent after they were comprehensively explained about surgical risks and research objectives.

Surgical operation of hysteroscopic suture fixation of the LNG-IUS

The LNG-IUS (Mirena®, Bayer), containing 52 mg levonorgestrel, was utilized in this study. All procedures were performed using a 26-Fr hysteroscopy endo-operative system (Sopro-Comeg, France) equipped with a 13-Fr working channel. The irrigation system maintained intrauterine pressure at 80–100 mmHg using warmed normal saline (0.9% NaCl), monitored in real-time by an integrated pressure sensor. Intravenous infusion of 80 mg of phloroglucinol was administered for cervical ripening 15 min before surgery20,21. Patients were placed in the dorsal lithotomy position under general anesthesia. The depth of the uterine cavity was measured after surgical field sterilization, and hysteroscopy was initiated. If endometrial thickening or polyps impeded visualization, diagnostic curettage or transcervical resection of polyps was performed before LNG-IUS fixation.

The tail wire of the LNG-IUS and one end of a 2 − 0 braided non-absorbable suture with two 26 mm 1/2-circle tapercut needles (Ethibond EXCEL™ W6977M, Ethicon) were trimmed. The suture midpoint was secured at the junction of the LNG-IUS arms. A 3-mm needle holder clamped the suture at 2–3 cm distance from the needle; subsequently, under hysteroscopic guidance, the suture was inserted into the uterine cavity. The suture was anchored to the anterior or posterior uterine wall near the fundal midline, penetrating the superficial myometrium (Fig. 1a). The transverse arm of the device was aligned parallel to the uterine fundus, and the suture was incrementally withdrawn under hysteroscopic visualization to ensure snug apposition (Fig. 1b). The knot was tied outside the body and pushed to the knotting site through a knot pusher. Each knot placement was confirmed hysteroscopically; adjustments were made with the needle holder as required. A total of 5 to 6 knots were tied during the operation. Next, after cutting the suture was excised at 1 cm from the final knot, and the procedure was completed by hysteroscopic re-evaluation to confirm the proper positioning of the LNG-IUS (Fig. 1c). All surgeries were performed by two designated gynecological surgeons in our department. All patient identifiers (e.g., medical device serial numbers) were removed from the images using Gaussian blurring and pixelation techniques.

Perioperative safety check

Before the operation, accurately examine the position and size of the uterus. Pre-treat the cervix, and slowly dilate during the operation. Adopt the hydraulic dilation mode of opening the inflow valve and closing the outflow valve to ensure direct access into the uterine cavity. Perform the operation under clear vision to avoid the occurrence of uterine perforation. If necessary, synchronous monitoring with a gynecological ultrasound during the operation can be performed. If there is a sudden loss of vision during the operation, be alert for uterine perforation. Pay attention to the bleeding in the uterine cavity during the operation. If necessary, perform bipolar electrocoagulation hemostasis or use oxytocin to promote uterine contraction and reduce bleeding21. Before the operation, administer 1.5 g of cefuroxime intravenously to prevent infection (if allergic to cephalosporin drugs, then administer 300 mg of etimicin intravenously).

After the operation, if the patient is conscious, with stable respiratory and circulatory functions, has little vaginal bleeding, and can move around freely, they can be prepared for discharge. Before discharge, the patient was assessed using the Postanesthesia Discharge Score (PADS). They could be discharged only if the score was above 822.

Follow-up

Patients were monitored for a minimum of 1 year postoperatively through follow-up visits at the outpatient clinic of the Second Hospital of Shandong University. Evaluations were conducted at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months following the placement of the device. Baseline and follow-up assessments included measurements of height, body weight, body mass index, ultrasound-derived uterine volume, visual analog scale (VAS) scores, menstrual bleeding scores, and serum hemoglobin (Hb) levels.

Evaluation methods

TVUS diagnosed adenomyosis based on the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) criteria established by the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis Group23. Direct features include intramyometrial cysts, hyperechogenic islands and echogenic subendometrial lines and buds. Indirect features include asymmetrical thickening, globular uterus, fan-shaped shadowing, translesional vascularity, irregular junctional zone and interrupted junctional zone. A diagnosis can be confirmed when at least one direct sign is found. If there are no direct signs, at least two indirect signs must be present, excluding fibroids or endometrial lesions, and reviewed by a gynecological ultrasound expert. Examinations were performed with standardized commercial probes to obtain images in the orthogonal plane, prioritizing the identification of ill-defined lesions or regions of abnormal echogenicity.

Dysmenorrhea severity was assessed based on the VAS score as follows: 0 (no pain), 1–3 (mild), 4–6 (moderate), and 7–10 (severe).

The Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) was used to quantify menstrual blood loss24. Scoring criteria were as follows: (1) mild [1 point]: the blood-stained area is one-third of the entire sanitary napkin area; (2) moderate [5 points]: the blood-stained area is one-third to three-fifth of the entire sanitary napkin area; and (3) severe [20 points]: the entire sanitary napkin is stained with blood. Blood clots were classified as follows: (1) small (1 point) - clots with diameter < 2.5 cm (approximating the size of a 1 yuan coin); (2) large (5 points) - clots with diameter ≥ 2.5 cm. The total PBAC score was derived by summing the sanitary napkin score and the clot score, with a threshold of ≥ 100 points indicating menorrhagia (corresponding to > 80 mL blood loss). Hb levels were used as an adjunctive efficacy measure, with anemia defined as an Hb level of < 110 g/L.

The uterine size was evaluated through standardized imaging protocols. Two ultrasound imaging specialists measured uterine dimensions through TVUS. The uterine volume was calculated as follows: 0.5233 × longitudinal diameter × anteroposterior diameter × transversal diameter.

Adverse reactions were categorized as follows: irregular bleeding (e.g., breakthrough bleeding); menstrual pattern changes (including frequent menstruation, oligomenorrhea, prolonged menstruation, or cycle shortening); and other systemic reactions (lower abdominal pain, breast tenderness, headache, acne, lower limb edema, hirsutism, mood fluctuations, ovarian cyst formation, weight gain ≥ 5 kg/year, and increased vaginal discharge). Amenorrhea and a shortened menstruation cycle were excluded from adverse reactions because of their potential therapeutic benefits.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint was defined as the expulsion rate of LNG-IUS at 12 months. The secondary endpoints included the clinically meaningful improvement of VAS/PBAC/Hb, incidence of adverse events (irregular bleeding, menstrual pattern changes, and other systemic reactions).

Clinically meaningful improvement was prospectively defined as meeting both:

-

1.

≥ 50% reduction in either VAS pain score or PBAC score, consistent with the effective standard established in the Expert Consensus of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis25.

-

2.

Anemia correction is defined as hemoglobin ≥ 120 g/L.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 23.0 was utilized for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) when normally distributed, or median (interquartile range, IQR) otherwise. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages [n (%)] and were compared through χ² test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests on model residuals (α = 0.10 threshold for skewness detection). For the results that conform to the assumption of normal distribution, repeated measures analysis of variance is used. For outcomes violating normality assumptions, non-parametric Friedman tests with Bonferroni-adjusted Wilcoxon signed-rank post hoc tests were applied. All primary outcomes are reported with exact p-values and 95% confidence intervals derived from bias-corrected bootstrap (10,000 iterations) for non-normal data. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

This study enrolled 47 patients with TVUS-based confirmed diagnosis of adenomyosis and treated with LNG-IUS suture fixation between October 2022 and January 2024. No patients were lost to follow-up. The mean age of the patients was 42.3 ± 5.3 years, and 16 patients (27.7%) reported prior LNG-IUS displacement or expulsion. In pretreatment metrics, the median of baseline VAS pain score (non-normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk p < 0.001) was 4 (IQR:2–6). The median of baseline PBAC scores (non-normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk p = 0.002) was 143 (IQR: 97–193). The mean Hb before surgery (normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk p = 0.36) was 104.63 ± 27.03 g/L. The mean follow-up duration was 18 months (range: 12–23 months). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients.

By December 2024, 1 patient (2.1%) experienced LNG-IUS expulsion at 3 months post-insertion. TVUS identified intrauterine device displacement in 2 patients (4.3%). Repeat hysteroscopy revealed the LNG-IUS tip was positioned 0.5–1 cm below the uterine fundus, with the lower edge not reaching the cervical internal os. The LNG-IUS remained in situ in these 2 patients.

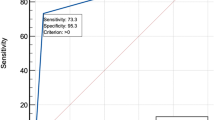

The severity of dysmenorrhea determined according to the VAS score. Before the treatment, 36 patients experienced dysmenorrhea. The VAS score at the first month (median [IQR]: 2 [1-4] ) after the operation was significantly lower than that before the operation (4 [2-6] adjusted p < 0.001). Furthermore, the VAS scores at the 3-month (2 [0–2]; adjusted < 0.001), 6-month (1 [0–1]; adjusted < 0.001) and 12-month (0 [0–1]; adjusted < 0.001) postoperative visits were all lower than those at the previous visit (Table 2; Fig. 2). Six months after the surgery, the VAS scores of the 35 patients (35/36, 97.2%) decreased by more than 50%.

Bonferroni-adjusted Wilcoxon tests indicated the PBAC score for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) at the 1st month after the surgery (median [IQR]: 105 [80–140] ) was lower than that before the surgery (143 [97–193]; adjusted p < 0.001). At the 3-month (95 [73–110]; adjusted p < 0.001) the 6-month (80 [62–95]; adjusted p < 0.001), and the 1-year (67 [54–80]; adjusted p < 0.001) follow-up after surgery, the PBAC scores were both lower than those in the previous assessment (Table 2; Fig. 3). Six months after the surgery, 29.8% of the patients experienced a decrease in PBAC of more than 50%. Twelve months after the surgery, the proportion of patients with a decrease in PBAC of more than 50% reached 55.3%.

Hb levels improved from 104.63 ± 27.03 g/L (95% CI: 96.79-112.49) at pre-treatment to 126.15 ± 9.95 g/L (95% CI: 123.26-129.04) at 12 months post-treatment (p < 0.001).

Adverse event profiles are comprehensively detailed in Table 3. Irregular bleeding was the most common adverse event (42.6%, 20/47), which led to clinical revisits in nearly 50% of the cases affected. Secondary side effects included prolonged menstrual bleeding (10.6%, 5/47), increased vaginal discharge (10.6%, 5/47), and weight gain of 5 kg or more (2.1%, 1/47). For patients experiencing irregular bleeding following surgery, we helped alleviate their anxiety by clearly explaining that such bleeding within 3 to 6 months post-surgery is a normal occurrence, which tends to decrease over time. For the five patients with increased bleeding, we provided some Chinese patent medicines such as Yunnanbaiyao capsules or tranexamic acid for hemostasis treatment. Additionally, we initially administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (like naproxen) to reduce uterine contractions and assess their response, thereby indirectly lessening the bleeding26. If symptoms remained unresponsive, we prescribed COCs for patients under 40 years old to help regulate hormonal levels, assist in endometrial repair, restore the shedding pattern, and control bleeding.

Two patients discontinued LNG-IUS therapy during follow-up: one patient due to persistent HMB (device removed at 8 months post-insertion) and the other patient due to unresolved dysmenorrhea and HMB (device removed at 10 months post-insertion). Both patients subsequently received GnRH-a therapy in outpatient care.

Discussion

Adenomyosis, a structural disorder involving benign infiltration of stroma and endometrial glands into the myometrium, substantially affects the health of reproductive-aged women. Symptoms such as dysmenorrhea and HMB profoundly impair patients’ quality of life. While total or subtotal hysterectomy remains the gold standard curative intervention according to international guidelines, it leads to permanent loss of fertility. Recent advancements in fertility-preserving therapies have prompted the development of novel pharmacological agents, surgical techniques, and therapeutic paradigms. Implementing customized conservative strategies—prioritizing uterine preservation and fertility protection based on patients’ clinical profiles—is critical for optimizing adjunct assisted reproductive technologies and long-term disease management27.

Clinically, the LNG-IUS is utilized for managing adenomyosis-associated pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding. The therapeutic benefits of the dual action of LNG include direct targeting of ectopic endometrial implants and modulation of inflammatory mediators and angiogenic factors within the uterine microenvironment. At the cellular level, the elevated local LNG concentration suppresses estrogen receptor expression, inhibiting estrogen-dependent endometrial proliferation and inducing glandular atrophy. Concurrently, progesterone receptor (PR)-mediated activation of the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway promotes fibrotic remodeling of lesions and apoptosis of aberrant cells. Furthermore, LNG attenuates adenomyosis-related pain and restricts lesion progression by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, thereby altering the inflammatory milieu28,29,30,31.

The LNG-IUS demonstrates clinical efficacy in alleviating adenomyosis-related symptoms, with studies reporting improved quality of life outcomes (relief from symptoms and less incidence of adverse effects) comparable to those achieved with surgical interventions. However, adenomyosis frequently coexists with uterine enlargement or structural distortion, which may compromise its retention and therapeutic performance. Reported expulsion rates range from 8.7% to 37.5%32,33,34,35. Adenomyosis, previous cesarean delivery, HMB, dysmenorrhea, pre-insertion receipt of GnRH-A therapy, and uterine volume ≥ 200 cm3 are high-risk factors for LNG-IUS expulsion32,36,37.

Novel fixation techniques have been explored to address expulsion risks. Gu et al. modified the LNG-IUS by using a frameless fixed intrauterine device (GyneFix®). The 5-year LNG-IUS expulsion rate of the modified group was only 4.3% compared to 17% in the original system placement followed by the GnRH-a treatment group38. Tong fixed the LNG-IUS by a hysteroscopic suture, and the expulsion rate was 2.6% during 1 year of follow-up, which was lower than that previously reported39. In previous studies on the routine placement of LNG-IUS, the expulsion of LNG-IUS usually occurred within 1 year after implantation33,34. The follow-up period of our study was at least 1 year, up to 24 months, with an average of 18 months, covering the peak period of IUD detachment to a large extent. In our study involving 47 patients who underwent hysteroscopic suturing with follow-up of more than 1 year, one patient experienced the LNG-IUS expulsion three months after the operation, which could be potentially attributed to insufficient suture depth. After adjusting for age and parity, we compared our research to matched historical control groups and found that the expulsion rate of LNG-IUS after suturing fixation was 2.1% (95% CI: 0.3% − 11.1%), lower than that reported in previous literature (2.1% vs. 13.4%, p = 0.04)32,33,34,35. This indicates that suturing fixation may reduce the expulsion rate of LNG-IUS within a short period compared with that reported before. But this single-arm study cannot isolate the effect of suturing from confounding variables.

Notably, 94% (44/47) of the patients reported satisfaction, which correlated with a marked reduction in the incidence of dysmenorrhea and HMB. The most frequently reported adverse event during follow-up was irregular uterine bleeding, occurring in 42.6% of the patients. Post-insertion spotting incidence aligned with prior findings16,33, with the hysteroscopic sutured LNG-IUS and conventional placement groups showing no significant difference in this parameter. Notably, spotting constituted the primary rationale for LNG-IUS removal. While most patients presenting with breakthrough bleeding reported symptom acceptance after counseling, 5 patients required pharmacological intervention (e.g., tranexamic acid) to mitigate bleeding severity. Additionally, 2 patients (4.3%) exhibited persistent HMB or dysmenorrhea refractory to LNG-IUS therapy, prompting device removal and subsequent GnRH-a therapy. Although the majority of patients showed favorable treatment results, a few patients still suffered from dysmenorrhea and excessive menstrual flow, which affected their satisfaction with LNG-IUS treatment.

Due to the presence of patients with a history of intrauterine device (IUD) expulsion in the research group, this factor affected the establishment of a control group for this study. This study’s single-arm design limits our ability to attribute reduced expulsion rates solely to the suturing technique. Unmeasured confounders, such as operator experience or patient anatomy, may influence outcomes. Besides, the convenience sampling design and limited sample size may reduce generalizability.

Although our follow-up period has covered the peak period of IUD expulsion, the effective release period of LNG is 5 years. Further follow-up observations are needed to determine whether other patients will experience IUD expulsion or other adverse reactions during the subsequent treatment process.

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that in the future, it is very necessary to verify the effectiveness of this surgery through a larger sample size, longer follow-up (up to 5 years), and reasonable patient grouping.

Although prior research has predominantly focused on expulsion rates and therapeutic efficacy of the LNG-IUS, the potential influence of uterine cavity depth on clinical outcomes remains unexamined. Further investigation is required to elucidate whether excessive uterine cavity depth or uterine volume adversely influences treatment success. Additionally, future studies must establish standardized eligibility criteria for this procedure, including defining the optimal uterine size threshold and cavity depth parameters. Notably, systematic clinical data analyses should be conducted to determine whether the efficacy of LNG-IUS suture fixation depends on specific uterine dimensions (e.g., maximum cavity depth) and to identify evidence-based volumetric limits for patient selection.

Data availability

The datasets utilized in this study are currently unavailable in the public domain as they are part of an ongoing research study. De-identified individual data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Gordts, S., Grimbizis, G. & Campo, R. Symptoms and classification of uterine adenomyosis, including the place of hysteroscopy in diagnosis. Fertil. Steril. 109 (3), 380–388e1 (2018).

Naftalin, J. et al. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum. Reprod. 27 (12), 3432–3439 (2012).

Puente, J. M. et al. Adenomyosis in infertile women: prevalence and the role of 3D ultrasound as a marker of severity of the disease. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 14 (1), 60 (2016).

Upson, K. & Missmer, S. A. Epidemiology of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod. Med. 38 (2–03), 89–107 (2020).

Bulun, S. E., Yildiz, S., Adli, M. & Wei, J. J. Adenomyosis pathogenesis: insights from next-generation sequencing. Hum. Reprod. Update. 27 (6), 1086–1097 (2021).

Habiba, M., Benagiano, G. & Guo, S. W. An appraisal of the tissue injury and repair (TIAR) theory on the pathogenesis of endometriosis and adenomyosis. Biomolecules, 13(6). (2023).

Kobayashi, H. Endometrial inflammation and impaired spontaneous decidualization: insights into the pathogenesis of adenomyosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, 20(4). (2023).

Li, Q. et al. The pathogenesis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: insights from single-cell RNA Sequencingdagger. Biol. Reprod. 110 (5), 854–865 (2024).

Bulun, S. E. et al. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: shared pathophysiology. Fertil. Steril. 119 (5), 746–750 (2023).

Dason, E. S. et al. Guideline 437: diagnosis and management of adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 45 (6), 417–429e1 (2023).

Harada, T. et al. The Asian society of endometriosis and adenomyosis guidelines for managing adenomyosis. Reprod. Med. Biol. 22 (1), e12535 (2023).

Brun, J. L. et al. Management of women with abnormal uterine bleeding: clinical practice guidelines of the French National college of gynaecologists and obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 288, 90–107 (2023).

Pontis, A. et al. Adenomyosis: a systematic review of medical treatment. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 32 (9), 696–700 (2016).

Choudhury, S., Jena, S. K., Mitra, S., Padhy, B. M. & Mohakud, S. Comparison of efficacy between levonorgestrel intrauterine system and dienogest in adenomyosis: a randomized clinical trial. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health. 18, 26334941241227401 (2024).

Etrusco, A. et al. Current medical therapy for adenomyosis: from bench to bedside. Drugs 83 (17), 1595–1611 (2023).

Li, L. et al. [A prospective cohort study on the impact of placement timing of LNG-IUS for adenomyosis]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 96 (30), 2415–2420 (2016).

Zhu, L., Yang, X., Cao, B., Tang, S. & Tong, J. The suture fixation of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device using the hysteroscopic cold-knife surgery system: an original method in treatment of adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 116 (4), 1191–1193 (2021).

Browne, R. H. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat. Med. 14 (17), 1933–1940 (1995).

Lancaster, G. A., Dodd, S. & Williamson, P. R. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J. Eval Clin. Pract. 10 (2), 307–312 (2004).

Xu, D., Zhang, X. & He, J. Randomized comparison of intramuscular phloroglucinol versus oral Misoprostol for cervix pretreatment before diagnostic hysteroscopy. Int. Surg. 100 (7–8), 1207–1211 (2015). A Prospective.

Chinese Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy & C.S.o.O. and C.M.A. Gynecology. Chinese clinical practice guideline for hysteroscopic diagnosis and surgery (2023 update). Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 58 (4), 241–251 (2023).

Tong, J. L. et al. [Consensus of Chinese experts on hysteroscopy day surgery center set-up and management process]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi, 57(12): pp. 891–899. (2022).

Harmsen, M. J. et al. Consensus on revised definitions of morphological uterus sonographic assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: results of modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 60 (1), 118–131 (2022).

Halimeh, S., Rott, H. & Kappert, G. PBAC score: an easy-to-use tool to predict coagulation disorders in women with idiopathic heavy menstrual bleeding. Haemophilia 22 (3), e217–e220 (2016).

Lang, J. H., Chen, C. L. & Xiang, Y. Expert consensus of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids and adenomysis]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 53 (5), 289–293 (2018).

Madden, T., Proehl, S., Allsworth, J. E., Secura, G. M. & Peipert, J. F. Naproxen or estradiol for bleeding and spotting with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 206 (2), 129e1–129e8 (2012).

Han, L. et al. Individualized Conservative therapeutic strategies for adenomyosis with the aim of preserving fertility. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1133042 (2023).

Maruo, T. et al. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on proliferation and apoptosis in the endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 16 (10), 2103–2108 (2001).

Laoag-Fernandez, J. B., Maruo, T., Pakarinen, P., Spitz, I. M. & Johansson, E. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and adrenomedullin in the endometrium in adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. 18 (4), 694–699 (2003).

Gomes, M. K. et al. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on cell proliferation, Fas expression and steroid receptors in endometriosis lesions and normal endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 24 (11), 2736–2745 (2009).

Yun, B. H. et al. Effects of a Levonorgestrel-Releasing intrauterine system on the expression of steroid receptor coregulators in adenomyosis. Reprod. Sci. 22 (12), 1539–1548 (2015).

Harada, T. et al. Real-world outcomes of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for heavy menstrual bleeding or dysmenorrhea in Japanese patients: A prospective observational study (J-MIRAI). Contraception 116, 22–28 (2022).

Park, D. S. et al. Clinical experiences of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in patients with large symptomatic adenomyosis. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 54 (4), 412–415 (2015).

Zhang, L., Yang, H., Zhang, X. & Chen, Z. Efficacy and adverse effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in treatment of adenomyosis]. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 48 (2), 130–135 (2019).

Sheng, J., Zhang, W. Y., Zhang, J. P. & Lu, D. The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up study on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis. Contraception 79 (3), 189–193 (2009).

Magalhaes, J., Ferreira-Filho, E. S., Soares-Junior, J. M. & Baracat, E. C. Uterine volume, menstrual patterns, and contraceptive outcomes in users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: A cohort study with a five-year follow-up. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 276, 56–62 (2022).

Youm, J., Lee, H. J., Kim, S. K., Kim, H. & Jee, B. C. Factors affecting the spontaneous expulsion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 126 (2), 165–169 (2014).

Yang, H., Wang, S., Fu, X., Lan, R. & Gong, H. Effect of modified levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in human adenomyosis with heavy menstrual bleeding. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 48 (1), 161–168 (2022).

Lv, N. et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of hysteroscopic suture fixation of the Levonorgestrel-Releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 31 (1), 57–63 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients who participated in this clinical study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen C conducted statistical analysis and wrote the article; Liu Z and Liang Z performed the surgery and patient follow-up; Zhang P was the technical supervisor and reviewed the article; Dong Y conceptualized the clinical study design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Liu, Z., Liang, Z. et al. Hysteroscopic suture fixation for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in adenomyosis feasibility and therapeutic outcomes. Sci Rep 15, 39240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22880-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22880-9