Abstract

This paper addresses the critical challenge of fraud detection in medical insurance claims-a pervasive issue causing significant financial losses in healthcare-using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). Given the intricate nature of healthcare data, traditional fraud detection methods do not inherently capture the complex relationships and patterns among different entities. We explore the potential of GNNs to effectively identify fraudulent claims by modeling the interactions among various entities-such as patients, healthcare providers, diagnoses, and services-as a heterogeneous graph. We employ two state-of-the-art heterogeneous GNN architectures, HINormer (Heterogeneous Information Network Transformer) and HybridGNN, along with a modified homogeneous GNN, RE-GraphSAGE (GraphSAGE “Graph Sample and Aggregate” with relation embeddings), adapted to handle the heterogeneity of healthcare data. The models are evaluated on real-world claims datasets of different sizes, comprising millions of medical activities. For the small-size claims dataset, the HINormer architecture followed by the RE-GraphSAGE architecture achieved the highest F-score (84% and 83%, respectively). For the medium-sized claims dataset, RE-GraphSAGE followed by HINormer achieved the highest F-score (84% and 81%, respectively), and for the large-size claims dataset, HINormer followed by RE-GraphSAGE achieved the highest F-score (82% and 79%, respectively). Additionally, we apply explainability techniques, namely GNNExplainer and PGExplainer, to provide insights into the models’ decision-making processes and to examine their medical significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fraud detection in medical insurance claims is a critical challenge in the healthcare industry, resulting in substantial financial losses and undermining the integrity of healthcare systems globally1. Fraudulent activities in medical claims include billing for services not rendered, falsifying diagnoses, submitting duplicate claims, upcoding (charging for more expensive services than those provided), and unbundling (separating services that should be billed together to increase costs). These deceptive practices create a significant burden on healthcare resources, inflating costs and diverting funds from genuine medical needs. Fraud and abuse contribute significantly to waste, with U.S. estimates ranging from $58 to $84 billion annually, and global reviews suggest 3–10% of health spending may be lost to fraud, undermining payer sustainability and patient trust.2,3

The complexity of medical claims fraud is heightened by the variety of schemes employed by fraudsters. For example, some schemes involve collaboration among multiple parties, such as patients, providers, and pharmacies, to submit false claims4. Manual claims review is time-consuming and inefficient for detecting complex fraud patterns, reinforcing the need for automated analytics5 Furthermore, the continuously evolving nature of fraud tactics requires detection systems to be adaptable and capable of learning from new patterns.

Traditional methods for detecting fraud in medical insurance claims, such as rule-based systems, statistical analyses, and even conventional machine learning and deep learning models, often fall short due to the complexity of healthcare data. Rule-based systems rely on predefined rules and thresholds to flag suspicious claims, but they can be rigid and may miss new or sophisticated fraud patterns that do not fit the existing rules. Statistical analyses, while useful for identifying anomalies, often struggle to capture the intricate relationships and patterns inherent in fraudulent activities. Standard tabular models (e.g., trees, boosting, MLPs) operate on independent records and do not natively capture multi-entity relations (patient–provider–service–diagnosis), whereas graph neural networks are expressly designed to learn from such relational structure, and have shown benefits on health-insurance fraud tasks6 This limitation hinders their ability to effectively detect nuanced fraud patterns. All these methods can result in high false positive rates, where legitimate claims are incorrectly flagged as fraudulent, leading to unnecessary investigations and delays in claim processing.

Moreover, in insurance companies, the reliance on human experts to manually review claims is both time-consuming and costly. Typically, human experts must scrutinize large volumes of incoming claims to identify potential fraud and decide which claims are accepted and which get rejected. This process requires extensive medical and procedural knowledge. Such manual review is not only labor-intensive but also prone to human error and subjectivity. As the volume and complexity of healthcare data continue to grow, the limitations of traditional methods and manual review, especially in capturing and understanding the complex relationships among entities in claims data, become increasingly apparent. This necessitates more efficient and accurate approaches to fraud detection that can effectively model these intricate relationships.

Healthcare claims data is inherently complex, encompassing a vast array of interactions between patients, clinicians, healthcare providers, diagnoses, and medical services. Each claim can involve multiple entities and services, creating a network of interconnected data points. This complexity poses a significant challenge for traditional fraud detection techniques, which cannot often model and analyze such multifaceted relationships effectively7. For instance, a single patient’s data may include interactions with multiple healthcare providers, various diagnoses, and a range of prescribed treatments, each adding layers of complexity to the data.

Consequently, there is a pressing need for more advanced and sophisticated approaches to fraud detection in medical insurance claims. Modern techniques must be capable of understanding and interpreting the intricate web of relationships within healthcare data. They should be able to detect not only overtly fraudulent activities but also subtle patterns and anomalies that might indicate fraud.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are an advanced class of deep learning models adept at analyzing graph-structured data, where they can process complex relationships and dependencies within a dataset by considering both node features and the connections between nodes8. This capability allows GNNs to capture and interpret intricate patterns in data, making them particularly effective for tasks where the relationships between entities are crucial8.

This paper explores the potential of GNNs as a powerful tool for combating medical fraud. In the context of medical fraud detection, a graph can represent a network of entities and their relationships. Nodes in the graph could represent patients, providers, medical services, diagnoses, and medications, while edges connect these entities based on interactions, claims submitted, and prescriptions dispensed.

GNNs are capable of learning representations of individual entities (nodes) by considering their relationships (edges) with other nodes in the graph. This allows GNNs to identify hidden patterns and anomalies in healthcare data networks that traditional methods might overlook. Here are some ways GNNs can contribute to reducing medical fraud:

-

Detecting Fraudulent Billing Rings: GNNs can identify clusters of patients, providers, and services engaged in coordinated fraudulent billing schemes by analyzing their relational structures.

-

Uncovering Abnormal Billing Patterns: Leveraging historical data, GNNs can detect anomalous claim submission patterns, such as excessive services billed for individual patients or repeated diagnoses for similar conditions.

-

Predicting Potential Fraud: By modeling relationships between past fraudulent activities and current claims data, GNNs can anticipate fraud attempts before they occur, enabling proactive mitigation strategies.

Heterogeneous GNNs, on the other hand, handle graphs with multiple types of nodes and edges. This allows them to more accurately model the varied interactions and relationships within the data, making them better suited for complex datasets like those found in healthcare claims. Heterogeneous GNNs can be further divided into metapath-based and metapath-free models. Metapath-based models utilize predefined metapaths to capture meaningful relationships in the heterogeneous graph. A meta path is a sequence of node types and edge types that define a specific schema or pathway through the graph to capture higher-order connectivity patterns between different types of entities. These manually selected metapath schemes often require expertise, and can lead to the loss of important information due to the transformation of complex graph structures into simplified metapaths. Examples of metapath-based models include HetGNN9, HAN10 and MAGNN11. Metapath-free models do not rely on predefined metapaths but instead use mechanisms to learn directly from the heterogeneous structure of the graph. Examples include HetSANN12 and Simple-HGN13.

Homogeneous and heterogeneous GNNs mostly rely on the message-passing paradigm introduced in 201714, where every node uses a function to create a message for each neighbor utilizing their features, then aggregates these messages to update its current representation.

Heterogeneous graphs, which represent entities and relationships of various types, add another layer of complexity to fraud detection. The diversity of node and edge types in healthcare data requires models that can effectively differentiate between different kinds of interactions. Heterogeneous GNNs excel in this task by incorporating the heterogeneity of the data and learning rich representations that highlight potential fraud.

Another critical aspect of employing GNNs for fraud detection is the explainability of their predictions. In the context of healthcare, where decisions can significantly impact patient care and financial outcomes, it is crucial to understand the reasoning behind the model’s decisions. Explainability techniques for GNNs, such as GNNExplainer15 and PGExplainer16, help in interpreting the models by identifying which parts of the graph (nodes, edges, or features) were most influential in the model’s predictions.

Explainability not only aids in validating the model’s decisions but also enhances trust within the healthcare system by providing transparent insights into how fraud is detected. By analyzing the explanations of the model’s prediction, we can understand whether the model is correctly identifying the fraudulent patterns in claims data, such as unusual billing patterns or suspicious relationships between providers and patients. In summary, this paper investigates the potential of utilizing GNNs for fraud detection in real-world medical insurance claims by leveraging their ability to model complex relationships within heterogeneous healthcare data. Our study not only explores the effectiveness of these advanced models but also delves into their interpretability using explainability techniques.

The objective of this study is to investigate the potential of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for fraud detection in real-world large healthcare claims data, where the data can be naturally represented as a heterogeneous graph. Claims data involves multiple entities-patients, providers, diagnoses, services-interacting in complex ways, and GNNs are well-suited to model these interactions. This work also aims to fill the gaps in existing literature by exploring whether GNN explainers (originally designed for homogeneous GNNs) can be used to explain decisions in heterogeneous settings, where multiple node and edge types exist. Moreover, the study is going to assess the practical utility of these explainers in real-world scenarios, focusing on whether they can provide actionable, interpretable insights that enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of fraud detection models. To guide this investigation, the following research questions are posed:

-

Can GNNs be effectively applied to heterogeneous healthcare claims data to classify activities as accepted or rejected?

-

Can GNN explainers, originally designed for homogeneous GNNs, be adapted to explain decisions in heterogeneous settings, where the entities and relationships are more complex?

-

Do these GNN explainers provide valuable insights in real-world healthcare fraud detection scenarios, where interpretability and transparency are crucial for stakeholder trust?

Related works

Recent advances in deep learning have shown significant promise in healthcare applications. For example,17 presents a holistic approach to cardiovascular disease diagnosis by integrating machine learning and deep learning models, demonstrating improved diagnostic accuracy over traditional methods. Similarly, an ensemble deep learning model for predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease is introduced18, leveraging deep learning techniques to achieve high accuracy and robustness in cardiovascular disease prediction.

Recently there has been a surge in using Graph Neural Networks (GNN) to leverage the information residing within the relations between different entities in graph-structured data6. However, the application of GNNs in the context of medical claims data is not yet widely explored. This niche area holds significant potential due to the complex and interconnected nature of healthcare data. In19, researchers proposed a method for medical insurance fraud detection using a spatiotemporal constraint graph neural network (StGNN). The study constructed multiple heterogeneous graphs from medical insurance datasets, capturing spatial and temporal attributes of fraudulent patients. They employed multi-semantic metapaths to sample groups with the same behavioral trajectory and utilized a two-layer attention mechanism to assign weights to neighboring nodes and different behavioral trajectories. The StGNN model integrates these spatiotemporal constraints with graph neural network architecture to detect both gang fraud and individual anomalies effectively. Extensive experiments on real datasets demonstrated that StGNN outperforms existing methods in anomaly detection tasks, showcasing its capability to utilize both feature and topological information for robust fraud detection. MHAMFD model, introduced in20, utilizes an attributed heterogeneous information network (AHIN) along with a hierarchical attention mechanism to improve fraud detection. MHAMFD captures behavioral relationships at different levels of a patient’s visits, enhancing the feature representation of various objects in healthcare scenarios. By aggregating complex semantic information, the model offers interpretability by identifying key factors contributing to fraudulent behaviors.

Additionally, a Hierarchical Multi-modal Fusion Graph Neural Network (HMF-GNN) was introduced in21 for health insurance fraud detection. This model addresses the challenge of integrating longitudinal and multi-modal data from heterogeneous neighbors. Health insurance records are represented as a dynamic heterogeneous graph to capture topological information, longitudinal and multi-modal embeddings. The hierarchical multi-modal fusion strategy within the model aggregates intra-modality, inter-modality, and temporal information to enhance the detection performance.

Hong et al.22 proposed Multi-channel Heterogeneous Graph Structured Learning (MHGSL) method, to capture different information from healthcare data. This approach constructs three types of graphs from the data, each capturing different information: topology graph containing the original graph structure, feature graph capturing similarities between nodes in feature space, and semantic graph with higher-order similarities between nodes. By applying a single GCN to each graph type, and another GCN with shared parameters between graphs, they can learn differences and commonalities between graphs. Despite the advancements these models offer, a common challenge across these studies is the lack of explainability. While they focus on improving detection accuracy, they do not provide clear insights into the reasoning behind model predictions. This gap is particularly problematic in applications like healthcare fraud detection, where transparency and trust in model decisions are crucial for practical deployment.

In recent years, Explainable AI (XAI) has gained significant momentum, driven by the need for transparency and trust in AI models, especially for black-box models like GNNs23,24.

Over time, different methods have been developed to improve the explainability of GNN models. Broadly, they can be divided into two categories: instance-level and model-level explanations. Instance-level methods, such as GNNExplainer and PGExplainer, focus on explaining predictions for individual instances by identifying important nodes, edges, or subgraphs. Model-level methods, like XGNN, aim to provide a general understanding of the model’s behavior by generating representative explanations that summarize the model’s decision-making process across multiple instances25.

The choice of HINormer and HybridGNN as heterogeneous GNN models was guided by their alignment with the unique requirements of our healthcare claims dataset and their state-of-the-art capabilities. Specifically, we prioritized the models that are:

-

Compatible with heterogeneous data, including the ability to handle varying feature sizes for different node types.

-

Demonstrated advantages and were recently published.

-

Publicly available (open-source code) implementation, facilitating integration with PyTorch Geometric.

As for RE-GraphSAGE, a modification of GraphSAGE designed to handle heterogeneous graphs26, we included it to assess whether such adaptations could achieve results comparable to state-of-the-art heterogeneous GNNs on real-world claims data. Initial experiments demonstrated promising performance, suggesting that this approach not only offers a viable alternative with simpler preprocessing requirements but also enables leveraging the extensive research on homogeneous GNNs in heterogeneous settings. Unlike most existing studies that use GNN in healthcare insurance fraud detection, which mainly focus on classifying patients as fraudulent based on their claims history, our work takes a deep look at the activity level within individual claims. This means we classify each activity in a medical claim as either fraudulent or not, recognizing that even within a single claim from the same patient, some activities may be accepted while others are rejected. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to leverage GNN architectures for activity-level fraud detection in healthcare claims, providing a novel approach to identifying fraud patterns at this granularity.

Research gap and study aims:

Existing fraud-detection studies on claims data have largely modeled risk at the provider or patient level, where labels and patterns differ markedly from those at the activity level (each medical service within the claim). Prior graph approaches in health insurance (e.g., spatiotemporal or heterogeneous GNNs) demonstrate promise but typically (i) operate above the activity granularity and (ii) provide limited explainability geared to heterogeneous graphs. As a result, there is little evidence on whether GNNs can (a) classify individual activities within a claim, (b) scale on real-world, multi-million-node heterogeneous claims graphs, and (c) produce clinically meaningful explanations in such settings.

Our approach: Unlike most existing healthcare-insurance fraud studies that use GNNs to flag patients or providers, we operate at the activity level within individual claims. That is, we classify each activity in a medical claim as accepted or rejected, acknowledging that even within a single claim some activities may be accepted while others are rejected. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate GNN architectures for activity-level fraud detection on large, real-world heterogeneous claims data and to assess instance-level explanations for such models with medical expert review. We address the gap above by evaluating heterogeneous and adapted homogeneous GNNs for activity-level detection, and by assessing the plausibility of instance-level explanations on heterogeneous data.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

We explored two state-of-the-art heterogeneous Graph Neural Network (GNN) architectures, namely HINormer and HybridGNN, on real-world healthcare fraud datasets comprising 6 million data points.

-

We compared these natively heterogeneous GNN architectures with homogeneous architectures adapted for heterogeneous settings, specifically RE-GraphSAGE, as proposed in 26.

-

We applied GNNExplainer and PGExplainer to HINormer and RE-GraphSAGE (the best-performing models) to interpret model decisions. To our knowledge, this is the first application of graph explainers on heterogeneous graphs within the medical claims domain.

-

We analyzed specific case studies from the explainers’ results from a medical perspective to evaluate their practical applicability and reliability in fraud detection.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Materials and Methods presents the data preparation, model architectures, and evaluation metrics. Experimental Results and Comparisons describe the performance of the proposed models. Finally, Conclusion summarizes the key findings and future directions.

Material and methods

In this section, we first describe the data used in the study, including its size, features, and the preprocessing steps performed. We then introduce the GNN models we trained on this data, followed by the baseline ML models used for comparison. Next, we provide an overview of the explainer models employed to interpret the decisions of the GNN models. Finally, we discuss the metrics used to evaluate both the GNN models and the explainers.

Dataset description

The data originates from real-world medical insurance claims in the MENA region, initially represented in tabular format, containing multiple claims with associated medical services and diagnoses, along with information about the patients, clinicians, and providers. Each claim may contain multiple medical activities, which can be either accepted or rejected by the insurance company. For our experiments, we used balanced datasets by including an equal number of accepted and rejected activities, with rejections limited to those flagged for medical reasons.

To leverage the relationships between entities within the data, we converted the tabular data into a heterogeneous graph. This graph representation allows GNN models to capture complex relationships and dependencies within the healthcare claims data.

We identify seven types of entities from the data, which serve as the nodes of the heterogeneous graph: patient, clinician, service, diagnosis, claim, provider, and activity, as described in Table 1.

Furthermore, we define nine types of relationships between these nodes, which form the edges of the graph. These edges represent the connections and interactions between different entities within the claims data: activity_for_patient, activity_executedBy_clinician, activity_contains_service, activity_primary_diagnosis, activity_secondary_diagnosis, activity_rfv_diagnosis, activity_partOf_claim, activity_by_provider, and diagnosis_requires_service, as described in Table 2.

Figure 1 illustrates the constructed heterogeneous graph, showing the different nodes and edges with a sample of three activities across two different claims. The primary objective is to classify activity nodes as either fraudulent or normal.

We used three different data sizes: small-sized data containing 490,879 activities, medium-sized data containing 2 million activities, and large-sized data containing 6 million activities. Detailed node counts for each data size are provided in Table 3.

For each data size, we employ a consistent split strategy for training, validation, and testing. Specifically, 80% of the activities (with all other entities related to these activities) are allocated for training, with the remaining 20% for testing. The training data is further divided such that 80% is used for training and 20% for validation. There is no overlap between the training set and test set for all 3 datasets (small, medium, large).

Preprocessing

The raw medical insurance claims data was initially presented in a tabular format. We transformed the tabular data into a heterogeneous graph structure using PyTorch Geometric27 by extracting the nodes with their associated features and edges as outlined in tables 1 and 2 respectively.

The raw medical insurance claims data was initially presented in a tabular format. To effectively apply Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), we transformed this data into a heterogeneous graph structure using PyTorch Geometric27. The transformation involved extracting the nodes and their associated features, as well as defining the edges based on the relationships between the entities, as outlined in Tables 1 and 2.

Feature Engineering:

The node features associated with each entity type in the graph were preprocessed as follows:

We preprocessed the features for each node type in the graph as follows:

-

Numerical Features: Numerical features like age or total claimed amount were subjected to min-max normalization to ensure all values fall within a range of 0 to 1.

-

Categorical Features: Categorical features such as patient gender, service category, or diagnosis group were transformed using one-hot encoding. This approach creates a new binary feature for each unique category within the original feature.

Missing Value Imputation: We adopted different strategies for handling missing values based on the type of feature:

-

Numerical Features: Missing values in numerical columns were imputed using the median value for that specific feature.

-

Categorical Features: Missing values in categorical columns were filled with a separate category labeled “unknown” to differentiate them from existing categories.

Model-Specific Preprocessing:

While the core preprocessing steps mentioned above were common to all models, additional preprocessing specific to the architectures is required: for HINormer, this includes generating target-node context, and for HybridGNN, generating aggregation flows.

While the core preprocessing steps mentioned above were common to all models, additional preprocessing specific to the architectures was required:

-

For HINormer: This includes generating target-node context, which involves sampling neighboring nodes in the graph to form the context for each target node.

-

For HybridGNN: This includes generating aggregation flows (aggregated representations computed along specific paths of neighboring nodes). These flows are derived in two ways: one that follows typical interaction patterns within the same relationship and another that randomly samples connections across different relationship types

GNN architectures

Three Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) architectures were used for representation learning of the nodes. Each node type in the heterogeneous graph is associated with specific features as mentioned in Table1, and these features are transformed into vector representations using GNN. The node embeddings are learned through message passing, where each node’s representation is updated based on its neighbors’ features and the relationships between them. To leverage the inherent relationships and the diverse entities in healthcare claims data, we used two state-of-the-art heterogeneous GNNs architectures. We used two state-of-the-art heterogeneous GNNs architectures. The first one, HINormer28, is a graph transformer-based approach designed to learn both structural and semantic information in heterogeneous graphs. HINormer utilizes two key components: the local-structure encoder, which enhances node embeddings by aggregating information from neighboring nodes to capture local structural patterns, and the relation encoder, which incorporates semantic relationships between the target node and its multi-hop neighbors, acting as positional encodings for the heterogeneous transformer. For each activity node, we sample a fixed number of neighboring nodes to construct its context, and the feature representation of these context nodes is then enhanced through the local-structure and relation encoders. These enriched features are fed into the heterogeneous graph transformer to generate refined representations for the activity nodes.

The first one, HINormer28, is a graph transformer-based approach that learns the graph structure and heterogeneity by using a local-structure encoder to enhance nodes’ embedding based on the local view, and a relation encoder that incorporates semantic relations between the target node and its D-hop node context, and acts as the positional encoding for the heterogeneous transformer.

For each activity node, we sample a fixed number of neighbors to generate its context. The features of each context node are enhanced through the local-structure encoder and the relation encoder to serve as the input to the heterogeneous graph transformer, generating embeddings for activity nodes.

The second heterogeneous GNN we used is HybridGNN29, originally designed for multiplex heterogeneous graphs. It generates metapath-based neighbors and integrates it with randomized exploration to construct multiple aggregation flows that capture different semantics of the heterogeneous graph along with the hierarchical attention mechanism.

HybridGNN decomposes the graph into multiple layers to construct the aggregation flows, where a graph layer is synonymous with the edge type in the data they used. Treating each edge type as a layer in our data will generate sparse layers, limiting HybridGNN ability to extract information from the aggregation flows30. To avoid this, our healthcare claims data can be viewed as a single-layer multiplex heterogeneous graph. It contains multiple node types and multiple edge types, where any two nodes are connected by at most one edge type.

The second heterogeneous GNN we used is HybridGNN29, originally designed for multiplex heterogeneous graphs. HybridGNN effectively captures complex interactions within such networks by integrating metapath-based neighbor sampling with randomized exploration, constructing multiple aggregation flows that capture different semantics of the heterogeneous graph. HybridGNN decomposes the graph into multiple layers to construct the aggregation flows, where a graph layer represents the graph filtered for certain edge type. Treating each edge type as a separate layer in our data will generate sparse layers, limiting the ability of HybridGNN to extract information from the aggregation flows30. To avoid this, our healthcare claims data can be viewed as a single-layer multiplex heterogeneous graph. It contains multiple node types and multiple edge types, where any two nodes are connected by at most by one edge type.

While heterogeneous GNNs are specifically designed to handle diverse node and edge types, some recent studies2613 suggest that homogeneous GNNs can potentially handle heterogeneous graphs without compromising the performance, which enables leveraging the advancement in homogeneous GNNs in heterogeneous settings.

To this end, we have additionally evaluated a homogeneous GNN, namely GraphSAGE31, modified as proposed in26 to handle the heterogeneity in the data. we refer to this modified version as “RE-GraphSAGE” and compare it with the natively heterogeneous GNNs.

GraphSAGE31 is a homogeneous GNN that aggregates the representation of neighboring nodes via a learnable aggregator. when modified according to26, GraphSAGE is capable of encoding the heterogeneity of claims data by incorporating one learnable parameter for each relation type, along with the node-type-specific transformation of node features.

In our data, each node type has a different number of features, so we used node-type-specific linear transformations to project the features of different node types into the same space.

While heterogeneous GNNs are specifically designed to handle diverse node and edge types, some recent studies2613 suggest that homogeneous GNNs can potentially handle heterogeneous graphs without compromising the performance, which enables leveraging the advancement in homogeneous GNNs in heterogeneous settings. To this end, we have additionally evaluated a homogeneous GNN, namely GraphSAGE31, modified as proposed by Wang et al.26 to handle the heterogeneity in the data. We refer to this modified version as “RE-GraphSAGE” and compare it with the natively heterogeneous GNNs. GraphSAGE31 is a homogeneous GNN that aggregates the representation of neighboring nodes via a learnable aggregator. When adapted as described by Wang et al.26, GraphSAGE is capable of encoding the heterogeneity of claims data by incorporating one learnable parameter for each relation type, along with the node-type-specific transformation of node features. Given that each node type in our claims data has a different set of features, we used node-type-specific linear transformations to project the features of different node types into the same space.

Baseline ML models

The last phase of any machine learning approach is classification. Random Forest32 and Support Vector Machines (SVM)33 were selected as baselines for comparison with our GNN based approach. Both models serve as classic benchmarks for machine learning tasks and have been commonly used in the context of Medicare fraud detection34, offering complementary perspectives on the performance of the GNN models. Both are well-suited for handling tabular data with a mix of categorical and numerical features35. Moreover, they are capable of automatically handling categorical features without the need for further preprocessing techniques, such as encoding. This capability is especially beneficial for datasets with high-cardinality categorical features, such as diagnosis and service codes, where traditional encoding methods can lead to an explosion in feature space. Both algorithms serve as classic benchmarks for machine learning tasks and have been commonly used in the context of Medicare fraud detection34, offering complementary perspectives on the performance of the GNN models.

GNN explainers

While GNNs have shown great promise in various applications, their decision-making process is often difficult to interpret, which highlights the importance of designing GNN explainers that can provide insight into the model’s decisions. Since research is still lacking in designing GNN explainers with heterogeneity in mind, we explored the applicability of existing GNN explainers, often used for homogeneous GNNs, in heterogeneous settings by employing two common GNN explainers, namely GNNExplainer15 and PGExplainer16.

Research is still lacking in designing GNN explainers with heterogeneity in mind. To explore the applicability of existing GNN explainers in heterogeneous settings, we employed two common GNN explainers, namely GNNExplainer15 and PGExplainer16.

GNNExplainer15 is a model-agnostic explainer that can learn both the important edges (edge mask) and node features (node features mask) that influenced the model’s decision for a certain target node. The masks are treated as learnable parameters as the explainer optimizes the mutual information between the model’s predictions using the original graph, and its predictions using the masks.

PGExplainer16 takes a probabilistic approach by modeling the graph structure as edge distribution which can be used to sample the explanatory graph. This edge distribution is parametrized by an MLP that takes as input the edge embeddings, constructed by concatenating node representations provided by the GNN and generates the edge distribution parameters.

Implementation environment

We validated HINormer and HybridGNN on two different machines due to the significant time required for preprocessing, especially for medium and large datasets (as detailed in section Classification performance on different data sizes). One machine was used for small and medium datasets, while the other was dedicated to the large dataset. Detailed specifications of the resources and package versions on each machine are provided in Table 4. We used the original implementations of HINormer36 and HybridGNN37 ,with the only modification being incorporating the message-passing API used in torch-geometric (PyG) for subsequent compatibility with PyG’s explainers. which were initially developed using PyTorch. So to integrate PyTorch Geometric (PyG) explainers with the original HINormer and HybridGNN models, we modified the implementation to align the models with PyG’s message-passing framework, which is necessary for passing the models to PyG’s explainers. The original models used manual aggregation of nodes features, but we transitioned to PyG’s MessagePassing class which automates and optimizes this process. We subclassed MessagePassing, defining the message() and update() methods to handle information propagation and node feature aggregation efficiently. Additionally, we adopted PyG’s HeteroData class to represent graphs and ensure the models work seamlessly with PyG’s explainers. We also used the original implementation of RE-GraphSAGE which was implemented using DGL (Deep Graph Library) and compatible with the GNNExplainer and PGExplainer implemented also as part of DGL. We also used the original implementation of RE-GraphSAGE.

Validation criteria

To evaluate the GNN models, we employed the following metrics:

To evaluate the models and explainers, we used three levels of evaluation: first, we quantitatively assessed the performance of the GNN models in detecting fraudulent activities within the healthcare claims data; second, we evaluated the performance of the GNN explainers using quantitative metrics to measure their effectiveness in providing insights into the decision-making process of the models; and third, we conducted a medical expert evaluation of the GNN explainers, seeking feedback to validate the interpretability and practical relevance of the explanations provided by the models.

1- Fraud Detection Performance:

-

Macro-F1: Arithmetic mean of per-class F1 scores The arithmetic mean of the F1 scores across all classes, providing a measure of the model’s ability to classify both fraud and non-fraud activities correctly. It is calculated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} F1 = 2 \times \frac{\text {Precision} \times \text {Recall}}{\text {Precision} + \text {Recall}} \end{aligned}$$$$\begin{aligned} \text {Macro F1} = \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} F1_{i} \end{aligned}$$ -

Accuracy: Measures the overall correctness of the model’s predictions.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN} \end{aligned}$$where “TP” (true positives) refers to the rejected activities that were correctly labeled by the classifier as fraud, while “TN” (true negatives) are the accepted activities that were correctly labeled by the classifier. “FP” (false positives) are the accepted activities that were incorrectly classified as rejected activities, while “FN” (false negatives) are the rejected activities that were misclassified as accepted activities. :Measures the overall correctness of the model’s predictions, calculated as the ratio of correctly predicted activities (true positives and true negatives) to the total number of activities

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN} \end{aligned}$$where:

-

TP (True Positives) are the rejected activities correctly identified as fraud.

-

TN (True Negatives) are the accepted activities correctly identified as non-fraud.

-

FP (False Positives) are the accepted activities incorrectly classified as fraud.

-

FN (False Negatives) are the rejected activities incorrectly classified as non-fraud.

-

-

Preprocessing Time: Includes the time required for all preprocessing steps applied to the training set across all epochs (10 epochs), as well as the time for preprocessing the validation and test sets.

-

Training Time: Measures the time taken by the model to perform the forward pass and backpropagation for all epochs.

-

Inference Time: Represents the time required by the model to make predictions on the test set.

2- GNN Explainer Performance With Quantitative Metrics:

We used the following explainer evaluation metrics from38:

-

Fidelity+: Evaluates the quality of the explainer by removing the explanatory graphs (predicting using the complementary graph only \(G_{\text {comp}}\)). A \(\text {fid+}\) explanation close to 1 indicates necessary explanations (changes model predictions if removed).

$$\begin{aligned} \text {fid+} = 1 - \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \mathbbm {1}(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {comp}}} = \hat{y}_{i}) \end{aligned}$$ -

Fidelity-: Evaluates the quality of the explainer by generating predictions using only the explanatory subgraph \(G_{\text {exp}}\). A \(\text {fid-}\) score close to 0 indicates sufficient explanations.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {fid-} = 1 - \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \mathbbm {1}(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {exp}}} = \hat{y}_{i}) \end{aligned}$$ -

Characterization Score: Combines the \(\text {fid+}\) and \(\text {fid-}\) scores with the ability to balance between necessity and sufficiency using the weights \(w_{+}, w_{-} \in [0,1]\) respectively, where \(w_{+} + w_{-} = 1\).

$$\begin{aligned} \text {charact} = \frac{w_{+} + w_{-}}{\frac{w_{+}}{\text {fid+}} + \frac{w_{-}}{1 - \text {fid-}}} \end{aligned}$$ -

Medical Experts Validation: Aside from fidelity and characterization scores for evaluating the explainers, we have selected some examples to be evaluated by a medical expert.

We evaluated the quality of GNN explainers using the following metrics, as proposed by Amara et al.38:

-

Fidelity+: Assesses the necessity of the explanatory subgraph (the subset of the original graph that significantly influences the prediction on the target node) by measuring the change in model predictions when the subgraph is removed. A higher Fidelity+ score indicates that the explanation is crucial for the model’s decision-making process. It is calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Fidelity+} = 1 - \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \mathbbm {1}(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {comp}}} = \hat{y}_{i}) \end{aligned}$$where \(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {comp}}}\) denotes the model’s prediction using the complementary graph (i.e., the original graph minus the explanatory subgraph), and \(\hat{y}_{i}\) is the original prediction.

-

Fidelity-: Evaluates the sufficiency of the explanatory subgraph by observing the model’s performance when using only the subgraph for predictions. A lower Fidelity- score suggests that the explanation sufficiently captures the necessary information for accurate predictions. It is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Fidelity-} = 1 - \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \mathbbm {1}(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {exp}}} = \hat{y}_{i}) \end{aligned}$$where \(\hat{y}_{i}^{G_{\text {exp}}}\) represents the prediction using only the explanatory subgraph.

-

Characterization Score: Provides a balanced assessment by combining Fidelity+ and Fidelity- scores, allowing for the adjustment of emphasis between necessity and sufficiency through weights \(w_{+}\) and \(w_{-}\), respectively, where \(w_{+} + w_{-} = 1\). A higher Characterization Score indicates a more effective explainer. It is calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Characterization Score} = \frac{w_{+} + w_{-}}{\frac{w_{+}}{\text {Fidelity+}} + \frac{w_{-}}{1 - \text {Fidelity-}}} \end{aligned}$$By adjusting \(w_{+}\) and \(w_{-}\), one can tailor the evaluation to prioritize either the necessity or sufficiency aspects of the explanations.

3- GNN Explainer Performance Based On Medical Experts Validation: Aside from fidelity and characterization scores for evaluating the explainers, we have selected some examples to be evaluated by a medical expert.

Results and discussions

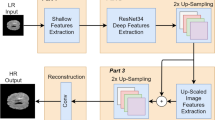

First, we utilized the small-sized data to train the three models (HINormer, HybridGNN, and RE-GraphSAGE) to determine the best hyperparameters. We then used these optimal hyperparameters to train the models on the medium and large-sized data. The organization of the results is shown in Fig. 2.

1- Technical validation

By conducting manual hyperparameter tuning on the small-sized data, we identified the most impactful parameters for each GNN model. Not all identified hyperparameters are common across all GNN models. The node embedding dimension is common between HINormer, HybridGNN and RE-GraphSAGE. Target node context sampling is a parameter for only HINormer. The number of sampled neighbors in aggregation flows is a parameter for only HybridGNN. Regarding the other parameters, for HINormer, we set the number of transformer layers to 1, the sequence length to 20, a dropout rate of 0.3 and Adam optimizer with learning rate of 1e-3. To train HybridGNN, we used Adam optimizer with the learning rate set to 1e-4. As for the metapath schemes that specify how different nodes should be connected and traversed to aggregate information during the learning process, we used the activity-diagnosis, service-diagnosis, and service-activity-diagnosis schemes to model the relationships between the activities, services, and diagnoses, enabling the detection of fraudulent behaviors by identifying misaligned activities with diagnoses, unnecessary services not justified by diagnoses, and inconsistencies in the combination of services, activities, and diagnoses that violate common medical practices. For RE-GraphSAGE, we used 2 layers, with a dropout rate of 0.1. Other hyperparameters were set to their default values.

Node embedding dimension

The node embedding dimension affects the ability to capture complex relationships within the graph data. As shown in Fig. 3, for both HINormer and HybridGNN, the node embedding dimension influenced performance. For HINormer, lower embedding dimensions were sufficient for capturing discriminative information for the nodes. In contrast, HybridGNN’s performance improved with increasing embedding dimension.

Target node context sampling

For graph transformer models like HINormer, the method used to sample the target node’s context can influence the performance. we explored different strategies for context sampling to understand their impact on performance. These methods vary in how they prioritize and sample neighbors around a target node:

-

Sampling from all 2 hops: This method involves aggregating both 1-hop (first neighborhood) and 2-hop (second neighborhood) neighbors of a target node into a single list and randomly sampling 20 nodes from this aggregated list. This approach can potentially mix immediate and extended neighbors without prioritizing their proximity to the target node.

-

1st hop then 2nd Hop sampling: Here, we first attempt to sample 20 nodes from the 1-hop neighbors of the target node. If the target node has fewer than 20 immediate neighbors, the shortfall is compensated by sampling from the 2nd-hop neighbors. This method ensures that closer nodes are prioritized, with more distant nodes only if the target node has small immediate neighborhood.

-

All 1st hop then sample iteratively from 1st hop neighbors: Like the previous method, we prioritize all 1-hop neighbors of the target node. If the total number of these neighbors is less than 20, we then sample additional nodes iteratively from each 1st-hop neighbor’s own neighbors, continuing this way until we reach the desired context of 20 nodes. This method prioritizes immediate neighbors and incrementally explores their neighborhoods.

Based on the results in Table 5, including 1-hop neighbors consistently yielded the best performance regardless of the sampling strategy used for the remaining hops. This suggests that focusing on the immediate neighborhood of the target node provides the most relevant information for HINormer.

Number of sampled neighbors

By changing the number of sampled neighbors at each step for the randomized exploration and metapath-based neighbors in HybridGNN, we observed that the model’s F1-score improved with an increasing number of sampled neighbors as depicted in Fig. 4, indicating that incorporating information from a wider neighborhood provides a more comprehensive view for accurate fraud detection.

This is consistent with the conclusion drawn earlier that the immediate neighborhood provides relevant information, where the inclusion of more neighbors resulted in better performance for HybridGNN. However, a further increase in the number of sample neighbors resulted in a decrease in HybridGNN performance. This might indicate that too large a neighborhood could introduce noise or irrelevant information, especially if the node has fewer neighbors, in which case the node itself is used as padding to reach the fixed number of sampled neighbors according to the original implementation.

Unlike HINormer and HybridGNN, RE-GraphSAGE exhibited minimal performance variations across different hyperparameter settings. This accounts for both the hyperparameters of the original GraphSAGE like the node embedding dimension and dropout probability, as well as the parameters associated with the modification like the gradient scaling factor. This might be due to its simpler homogeneous architecture, where the impact of specific hyperparameters might be less pronounced compared to the more complex HINormer and HybridGNN models. This also indicates that the relation embedding and node-type-specific feature projection were sufficient to capture the patterns in the heterogeneous data.

Classification performance on different data sizes

To evaluate the effectiveness of the GNN models for fraud detection in medical claims, we leveraged the best hyperparameter values we determined (achieved the highest accuracy) to train HINormer, HybridGNN, and RE-GraphSAGE models on the small, medium and large-sized datasets. That is, for the embedding dimension of HINormer and RE-GraphSAGE, we set it to 128, and for HybridGNN to 256. For HINormer we used 1st hop then 2nd hop sampling for the target nodes’ context, and we set the number of sampled neighbors in HybridGNN to be 9.

-

1.

Small-sized Data: As shown in table 6, both HINormer and RE-GraphSAGE show robust performance, achieving high Macro-F1 and accuracy scores of 0.84 and 0.83 respectively. These results highlight their effectiveness in capturing and leveraging the complex relations within the heterogeneous graph. In contrast, HybridGNN shows lower scores, with a Macro-F1 and accuracy of 0.71. This lower performance exhibited by HybridGNN might be due to the single-layer multiplex graph adaptation we made in our data, which blurred the model’s ability to differentiate between various edge types during the randomized exploration. The metapaths we used in HybridGNN to extract methapath-based aggregation flows (activity-diagnosis, service-diagnosis-service, activity-service) might not be optimal. However, identifying more effective metapaths that could potentially enhance HybridGNN’s performance, could be time-consuming and may require extensive experimentation.

-

2.

Medium-size Data: The performance and computational efficiency metrics are presented in Table 7. RE-GraphSAGE achieved the highest Macro-F1 score (0.84), followed by HINormer (0.81), suggesting a good balance between identifying true positives and minimizing false positives, unlike HybridGNN. The drop in HINormer’s performance compared to its performance on the small data might indicate that it requires separate fine-tuning or more epochs.

In terms of computational efficiency, RE-GraphSAGE demonstrated the fastest training and inference times due to its simpler homogeneous architecture. It also doesn’t require preprocessing beyond constructing the graph and basic preprocessing (normalization and one-hot encoding), unlike HINormer which requires context sampling, and HybridGNN which requires constructing the aggregation flows.

To reduce the preprocessing time and also avoid memory limitations, especially with HybridGNN due to the high embedding dimension, we divided the test set and validation set into 10 batches each. This batching however impacts the inference time, as processing the test data in smaller batches involves repeated matrix operations, unlike processing the entire test set at once. This also reduces the preprocessing time since the original implementation of HybridGNN’s preprocessing contains nested loops which would scale poorly having handled the whole test set at once. For HINormer, we parallelize the preprocessing across the available cores in all experiments. with larger data sizes, the parallization overhead became significant. So the preprocessing required for HINormer also benefited from batching the validation and test sets into 10 batches each. On the other hand, RE-GraphSAGE was able to handle the entire dataset without requiring such batching due to the minimal preprocessing required. The number of batches is summarized in table 8.

-

3.

Large-sized Data: The performance and computational efficiency metrics for the large-sized data are presented in Table 9. HINormer achieved a high Macro-F1 score of 0.82 and an accuracy of 0.82, maintaining robust performance even on the large-sized dataset. The increased complexity of the data resulted in a drop in HybridGNN’s performance compared to the medium-sized data. RE-GraphSAGE maintained a relatively high performance with a Macro-F1 score of 0.79 and an accuracy of 0.79 For the large data size, we split the validation and test sets for both HybridGNN and HINormer into 30 batches compared to 10 batches for the medium-sized data, which, along with the change in hardware architecture and pytorch versions, resulted in a significant increase in the total inference time for HybridGNN as shown in Fig. 5. When inspecting how the three different models behave as we scale the data, we notice that HINormer exhibits more performance stability compared to the other models as evident in Figs. 6 and 7, without changing the hyperprameters or requiring an increase in the number of epochs (which is held constant at 10 epochs for all models across different data sizes). It is also evident from Fig. 8 that RE-GraphSAGE requires significantly less preprocessing time compared to HINormer and HybridGNN, across the different data sizes While HybridGNN’s performance decreased as the data complexity increased, it is likely because adapting our data into a single-layer multiplex graph reduced the ability to express different edge types effectively, which introduced more confusion to the model with larger data. For RE-GraphSAGE, likely, the reduction in accuracy and macro-f1 scores for the large dataset was a result of requiring more epochs especially since it scaled well for the medium data size. Figure 9 shows a comparison between the training time (forward pass and backpropagation) for all three models across the different data sizes. We notice that HybridGNN benefits from the change in hardware architecture. This is evident by the significant reduction in training time as well as the inference time shown in Fig. 5 especially when compared to HINormer which shares the same batching strategy.

Comparison with baseline ML models

To assess the performance of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) relative to traditional machine learning models, we compared the results of the GNN architectures-HINormer, HybridGNN, and RE-GraphSAGE-against Random Forest and SVM. This evaluation was conducted on the small-sized dataset. The results are shown in Table 10.

The baseline comparison results reveal that HINormer and RE-GraphSAGE either matched or surpassed traditional models like linear SVM and Random Forest in terms of Macro-F1 and accuracy. Moreover, paired with explainers such as GNNExplainer or PGExplainer, GNNs provide insights that are more actionable and contextually meaningful than those offered by SHAP39 for traditional models. While SHAP focuses on feature-level contributions, GNN explainers can highlight specific relationships in graph-structured data-such as connections between a provider, diagnoses, and services-that drive fraud decisions. For example, GNN explainers can reveal that a provider frequently prescribes expensive services for unrelated minor diagnoses across multiple patients. This level of detail enables investigators to identify suspicious patterns tied to specific providers or claims, leading to targeted interventions and audits.

2- Explainability validation (Performance of GNN Explainers)

Next, we evaluate and validate the capability of the GNNs to explain their prediction results. We focused on explaining the predictions of the best-performing natively heterogeneous model, HINormer. In addition, we compared the explainability results for HINormer with those of the adapted homogeneous GNN, RE-GraphSAGE. We evaluated the explainers on a balanced subset of 10,000 activity nodes sampled from the test set. The explainers were trained to identify only the important edges that influenced the model’s decision.

Fidelity and characterization score metrics

The results in Table 11 show that, for HINormer, GNNExplainer achieves higher \(Fid+\) scores compared to PGExplainer, suggesting it identifies slightly more necessary edges for HINormer’s predictions, and that both explainers exhibit similar characterization scores, indicating a balance between necessity and sufficiency.

For RE-GraphSAGE, both explainers show lower \(Fid+\) and \(Fid-\) scores compared to HINormer. This suggests that RE-GraphSAGE’s predictions might rely less on relationships within the graph compared to HINormer.

These findings offer insights into the explainability of the GNN models. HINormer, with its ability to capture complex relationships in the heterogeneous graph data, appears to rely more on specific relationships to identify fraudulent activities. This is reflected in the higher \(Fid+\) scores achieved by GNNExplainer for HINormer. On the other hand, RE-GraphSAGE, with its simpler homogeneous architecture, might make predictions based on a broader set of features or potentially rely more on inherent node features compared to the relationships within the graph. This could explain the lower \(Fid+\) and \(Fid-\) scores for RE-GraphSAGE. Next, we examined some instances to investigate whether the performance of the explainers could provide insights into the model’s decision process.

Medical experts validation

In this subsection, we present real examples from the claims data, where the model successfully captures cases implying fraud or medical red flags. A medical expert was asked to review these cases based on best medical practices. We present examples of edge masks resulting from the explainers (GNNExplainer and PGExplainer) when applied to the GNN models, HINormer, and RE-GraphSAGE.

In each case, we show the original graph around the target activity node, highlighting the edge masks (important edges) identified by the explainers, while the rest of the graph is shaded. On each important edge, we display the importance score assigned to it by the explainer, ranging from 0 to 1. At the bottom of each figure, we present the following:

- The ground truth \(y\) for the case, - The model’s prediction given the full graph \(\hat{y}\), - The model’s prediction given the explanatory graph (important edges only) \(y_{\text {exp}}\), - The model’s prediction when given only the complementary graph \(y_{\text {comp}}\) (the original graph without the explanatory graph).

If the target activity node is accepted by the model (\(\hat{y} = 0\)), we show it in green. If it is rejected by the model (\(\hat{y} = 1\)), we show it in red.

First, GNNExplainer with HINormer:

Figure 10 shows the edge masks provided by GNNExplainer when applied to explain HINormer’s prediction for the target activity node. In the shown example, the rejected activity (colored in red) by HINormer is associated with the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) test. The explanation mask provided by GNNExplainer suggests that the direct connections to diagnoses R53.1 (Weakness) and R53.81 (Other malaise) were among the top five edges affecting HINormer’s decision for rejection, both with importance scores of 0.555. This conforms with the fact that these diagnoses do not provide sufficient justification for performing the LDH test. This case shows an agreement between the medical expert opinion and the edge mask generated by GNNExplainer.

Second, PGExplainer with HINormer:

The edge mask provided by PGExplainer to explain HINormer’s decision is shown in Fig. 11. The rejected activity by HINormer involves Antibody Rubella testing. Rubella is a viral infection that causes a distinctive rash and poses significant risks to pregnant women. Thus, testing for Rubella antibodies is essential for expectant mothers to protect the health of both the mother and the unborn child. This activity is associated with a patient who is a 30-year-old married female, with an importance score of 0.089, and with a clinician specializing in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, with an importance score of 0.088. Given these facts, the rejection of this activity is unjustified since a 30-year-old married woman could be pregnant. Therefore, the edges that the PGExplainer deemed significant for rejecting this activity are not medically substantial reasons for its rejection. Hence, the explainer results are not consistent with the medical expert’s opinion.

First, GNNExplainer with RE-GraphSAGE:

The edge mask provided by GNNExplainer to explain RE-GraphSAGE’s decision is shown in Fig. 12. The activity is associated with cyanocobalamin (a synthetic form of Vitamin B12). Cyanocobalamin is considered effective for treating or preventing vitamin B12 deficiency. Low levels of vitamin B12 can result from autoimmune diseases, pernicious anemia, certain surgeries, stomach disorders, or malnutrition40. The GNNExplainer identifies the diagnoses as a reason for rejecting this activity, assigning importance scores of 0.815 for R35.0 (Frequency of micturition), 0.777 for R51 (Headache), and 0.774 for M79.2 (Neuralgia and neuritis, unspecified), which do not justify the activity and therefore lead to rejection by RE-GraphSAGE. This shows consistency between the explainer’s decision and the medical expert’s opinion.

Second, PGExplainer with RE-GraphSAGE:

In Fig. 13, we observe that the PGExplainer provided good explanations for the rejection reasons and their significance, regarding the edges with the secondary diagnoses. The target activity (shown in red) involves surgical supplies. The diagnoses R51, described as “headache,” with an importance score of 0.553, and R42, described as “dizziness and giddiness,” also with an importance score of 0.553, are both valid reasons to reject this activity since they do not indicate any surgical-related diagnoses. In this case, the medical expert agrees with the explainer’s decision to highlight the rejection reason based on the connection between these diagnoses and this activity.

We can observe that PGExplainer generally assigns lower importance scores even to the top 5 edges compared to GNNExplainer, indicating less confidence in PGExplainer masks. The weights for edge masks for both explainers are also observed to be lower in HINormer compared to RE-GraphSAGE. This might be due to the complexity of HINormer, making it harder to identify important edges with higher confidence. That explains the results shown in Table 11.

Evaluating whether the models generalize on different datasets for the same task of activity-level fraud detection is currently unavailable due to the lack of publicly available data labeled specifically for this purpose. Despite its value, the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)41 claims data has primarily been utilized for provider-level fraud detection rather than activity-level detection. This distinction is crucial as the patterns and characteristics of fraud can vary significantly between these levels. Several studies35,42, have successfully employed CMS data for provider-level fraud detection. These studies often label CMS data using the List of Excluded Individuals and Entities (LEIE)43 maintained by the Office of Inspector General (OIG), which releases monthly updates listing providers prohibited from participating in Federal healthcare programs. If a provider’s ID appears on the list, it is considered fraudulent. However, there remains a gap in datasets that cater specifically to the granularity required for activity-level fraud detection. For the above reasons, CMS data cannot be applied to the GNN architectures proposed in this paper.

Conclusion

In this paper, we investigated the effectiveness of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for fraud detection in real-world medical claims data. We employed three GNN models – HINormer, HybridGNN, and RE-GraphSAGE – on a heterogeneous graph constructed from real-world medical insurance claims. Our findings showed that HINormer demonstrated robust performance across all dataset sizes. HINormer architecture achieved the highest F-score: 84% and 82%, for both small and large claims datasets, respectively. In contrast, RE-GraphSAGE achieved the highest F-score: 81% for the medium size dataset. While RE-GraphSAGE, a simpler homogeneous architecture with added encodings for the heterogeneity in the graph, achieved promising results for fraud detection compared to HINormer. Its short preprocessing, training, and inference times make it more favorable in practical settings, especially in terms of fine-tuning or training for more epochs. HybridGNN, while innovative in its hybrid aggregation flows and hierarchical attention mechanisms, faced challenges when applied to larger datasets. The model’s design to treat each edge type as a separate layer, and the subsequent decision to simplify the data into a single-layer multiplex heterogeneous graph, impacted its ability to extract nuanced information from the data, especially as the complexity increased. Analysis of the explainability techniques, that were previously designed and used in homogeneous settings, showed comparable performance on real-world heterogeneous data. However, when evaluated medically, it was found that sometimes the explanations provided did not correctly reflect the models’ decisions. The improvement and integration of these explainability tools could further enhance the value of GNNs. Unlike traditional explainability methods, these tools provide interpretable, relationship-level insights into the decision-making process, such as identifying suspicious links between providers, diagnoses, and services, which can enhance trust and transparency making them valuable for real-world applications.

Future research can build on the promising results of the modified GraphSAGE by exploring more complex homogeneous GNN models for fraud detection in heterogeneous healthcare claims data, potentially improving performance and representation learning. Additionally, developing explainers tailored to heterogeneous GNNs is crucial, as existing explainers for homogeneous models may not fully capture the complexities of heterogeneous graphs. This advancement would enhance model interpretability, making GNNs more transparent and effective for real-world applications, particularly in fraud detection.

Data availability

We retrospectively obtained claims data from Tachyhealth partner payer systems under existing data-use agreements. The raw data were extracted from production claim-processing databases and delivered to the research team fully de-identified prior to analysis; all direct identifiers were removed and quasi-identifiers generalized or masked according to HIPAA Privacy Rules44. Ethical oversight: Because this study used secondary, de-identified data collected for operations and analyzed retrospectively, it did not meet the definition of human subjects research under our institutional policies and was exempt from IRB/ethics review. The work was conducted under Tachyhealth’s internal ethics/compliance oversight, which confirmed that use of anonymized data for research complies with relevant standards and partner agreements. Consent: Individual consent was not required, as no identifiable information was used and the data-use agreements explicitly permit research use of anonymized data. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy but a sample will be provided upon request by the first author.

Code availability

Code is available at GitHub: https://github.com/Tachy-Health/GNN, and archived in Zenodo with the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17195566.

References

Hamid, Z. et al. Healthcare insurance fraud detection using data mining. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 24, 112 (2024).

du Preez, A., Bhattacharya, S., Beling, P. & Bowen, E. Fraud detection in healthcare claims using machine learning: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 103061, 856 (2024).

Shrank, W. H., Rogstad, T. L. & Parekh, N. Waste in the us health care system: Estimated costs and potential for savings. Jama 322, 1501–1509 (2019).

Mackey, T. K., Miyachi, K., Fung, D., Qian, S. & Short, J. Combating health care fraud and abuse: Conceptualization and prototyping study of a blockchain antifraud framework. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e18623 (2020).

Nabrawi, E. & Alanazi, A. Fraud detection in healthcare insurance claims using machine learning. Risks 11, 160 (2023).

Khemani, B., Patil, S., Kotecha, K. & Tanwar, S. A review of graph neural networks: Concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. J. Big Data 11, 18 (2024).

Hong, B. et al. Health insurance fraud detection based on multi-channel heterogeneous graph structure learning. Heliyon 10 (2024).

Lu, H., Wang, L., Ma, X., Cheng, J. & Zhou, M. A survey of graph neural networks and their industrial applications. Neurocomputing 128761 (2024).

Zhang, C., Song, D., Huang, C., Swami, A. & Chawla, N. V. Heterogeneous graph neural network. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 793–803 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Heterogeneous graph attention network. In The World Wide Web Conference, 2022–2032 (2019).

Fu, X., Zhang, J., Meng, Z. & King, I. Magnn: Metapath aggregated graph neural network for heterogeneous graph embedding. Proc. Web Conf. 2020, 2331–2341 (2020).

Hong, H. et al. An attention-based graph neural network for heterogeneous structural learning. In Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 34, 4132–4139 (2020).

Lv, Q. et al. Are we really making much progress? revisiting, benchmarking and refining heterogeneous graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 1150–1160 (2021).

Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O. & Dahl, G. E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1263–1272 (PMLR, 2017).

Ying, Z., Bourgeois, D., You, J., Zitnik, M. & Leskovec, J. Gnnexplainer: Generating explanations for graph neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

Luo, D. et al. Parameterized explainer for graph neural network. Adv. Neural Inf. Proc. Syst. 33, 19620–19631 (2020).

Sadr, H., Salari, A., Ashoobi, M. T. & Nazari, M. Cardiovascular disease diagnosis: A holistic approach using the integration of machine learning and deep learning models. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29, 455 (2024).

Saberi, Z. A., Sadr, H. & Yamaghani, M. R. An intelligent diagnosis system for predicting coronary heart disease. In 2024 10th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (QICAR), 131–137 (IEEE, 2024).

Chen, J.-P., Lu, P., Yang, F., Chen, R. & Lin, K. Medical insurance fraud detection using graph neural networks with spatio-temporal constraints. J. Netw. Intell. 7, 480–498 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Health insurance fraud detection by using an attributed heterogeneous information network with a hierarchical attention mechanism. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 62 (2023).

Zhang, J., Yang, F., Lin, K. & Lai, Y. Hierarchical multi-modal fusion on dynamic heterogeneous graph for health insurance fraud detection. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Hong, B. et al. Health insurance fraud detection based on multi-channel heterogeneous graph structure learning. Heliyon 10 (2024).

Clement, T., Kemmerzell, N., Abdelaal, M. & Amberg, M. Xair: A systematic metareview of explainable ai (xai) aligned to the software development process. Mach. Learn. Know. Extr. 5, 78–108 (2023).

Hassija, V. et al. Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cognitive Comput. 16, 45–74 (2024).

Yuan, H., Yu, H., Gui, S. & Ji, S. Explainability in graph neural networks: A taxonomic survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 5782–5799 (2022).

Wang, J., Guo, Y., Yang, L. & Wang, Y. Enabling homogeneous gnns to handle heterogeneous graphs via relation embedding. IEEE Trans. Big Data 9, 1697–1710 (2023).

Fey, M. & Lenssen, J. E. Fast graph representation learning with pytorch geometric. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.02428 (2019).

Mao, Q., Liu, Z., Liu, C. & Sun, J. Hinormer: Representation learning on heterogeneous information networks with graph transformer. Proc. ACM Web Conf. 2023, 599–610 (2023).

Gu, T. et al. Hybridgnn: Learning hybrid representation for recommendation in multiplex heterogeneous networks. In 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 1355–1367 (IEEE, 2022).

Wu, C. et al. Instant representation learning for recommendation over large dynamic graphs. In 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 82–95 (IEEE, 2023).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Proc. Syst. 30, 17 (2017).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 45, 5–32 (2001).

Cortes, C. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning (1995).

Hancock, J. T., Bauder, R. A., Wang, H. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. Explainable machine learning models for medicare fraud detection. J. Big Data 10, 154 (2023).

Hancock, J. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. Medicare fraud detection using catboost. In 2020 IEEE 21st International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), 97–103 (IEEE, 2020).

Ffffffffire. Hinormer. https://github.com/Ffffffffire/HINormer (2023). Accessed: 2025-03-27.

Scofield666. Hybridgnn. https://github.com/Scofield666/HybridGNN (2021). Accessed: 2025-03-27.

Amara, K. et al. Graphframex: Towards systematic evaluation of explainability methods for graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.09677 (2022).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.07874 (2017).

Multum, C. Cyanocobalamin. https://www.drugs.com/mtm/cyanocobalamin.html (2023). Accessed 2024.

Centers For Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: Physician and other supplier. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-charge-data/physician-and-other-supplier.html. Accessed: 2024.

Johnson, J. M. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. Medicare fraud detection using neural networks. J. Big Data 6, 63 (2019).

Office of Inspector General. Leie downloadable databases. https://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/exclusions_list.asp. Accessed: 2024.

Office for Civil Rights, H. Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information. final rule. Federal register 67, 53181–53273 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Zayed University for supporting this study through the Research Incentive Fund (RIF Grant No. 23010), with DT as the principal investigator. They also thank Tachyhealth Inc. for providing essential resources, including research assistance from MA and RM, and scientific direction from ATS. A thank you also goes to Professor Ravi Sharma for his support and guidance.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Incentive Fund (RIF Grant No. 23010) from Zayed University, with DT as the principal investigator. Essential resources were provided by Tachyhealth Inc., including research assistance from MA and RM, and scientific direction from ATS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M. conceived the experiments. R.M., D.T., A.N., and S.Y. conducted the experiments. M.A., M.A.A.E., and A.T.S. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article