Abstract

Meteorological factors are of crucial importance in foodborne disease (FBD) outbreaks, and more quantitative research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of meteorological factors on FBD outbreaks in Yantai from 2014 to 2024, using data reported by the Yantai Foodborne Disease Surveillance Network. The distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) was employed to model the exposure-response relationships between temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and FBD outbreaks. Prior to model fitting, multicollinearity among variables was addressed via the variance inflation factor (VIF). Results demonstrated non-linear relationships and complex correlations between these variables. Higher temperatures, greater precipitation, and slower wind speeds were associated with an increased risk of FBD outbreaks. In the lagged time dimension, temperature had an immediate effect that decayed after 2–3 weeks; the maximum lagged risk for precipitation occurred within 1–3 weeks; and wind speed showed subdued fluctuations. The lag patterns of high-value and low-value effects of different elements exhibited symmetry. These findings underline the necessity of integrating meteorological monitoring into FBD surveillance systems in accordance with their respective impact patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Foodborne diseases (FBD), encompassing any illnesses arising from the consumption of spoiled or contaminated food with disease-causing bacteria, viruses, parasites, toxins, pesticides, or drugs, pose a significant challenge to public health, and can also impede socioeconomic development by adversely affecting national economies, tourism, and trade1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that approximately 600 million people globally suffered from FBD each year2. Despite the fact that various countries were vigorously promoting the establishment of FBD surveillance networks, it was estimated that only a small fraction of these cases were currently recorded3. Additionally, the economic burden of FBD cannot be overlooked, because the World Bank estimated that the annual productivity loss due to unsafe food in low- and middle-income countries amounted to around $95 billion per year4.

FBD-inducing factors existed throughout the food chain, from primary production to final consumption, and their transmission routes were complex, involving multiple FBD pathogens as well as chemical and biological toxins3,5. Notably, numerous pathogens exhibited strong environmental persistence, which was especially crucial in the context of climate change. Reports have indicated significant associations between meteorological factors and FBD outbreaks6.

In recent decades, climate change and the rise in extreme weather events may further exacerbate this vulnerability, thus affecting the incidence of diseases such as food- and water-borne diseases5,7,8,9. Temperature, as an important indicator of climate sensitivity, has been incorporated into numerous studies on disease burden analysis10,11. A study in Europe indicated that warmer temperature and longer summer might lead to an increase in FBD outbreaks6. Moreover, the relationship between temperature and FBD, such as Salmonella and Campylobacter, was non-linear8,12,13,14. Besides temperature, altered precipitation conditions have also been associated with the onset of various FBD15,16, especially in some extreme precipitation events17,18. Some studies have proposed that extreme precipitation may be more likely than extreme heat to trigger infections such as Salmonella pathogens19. Alarming is the fact that some pathogens have demonstrated strong environmental adaptations and high stress tolerance to temperature change20,21,22. Compared with temperature and precipitation, the impact of wind speed was more complex and contradictory. Existing studies have shown that high wind speed can reduce the incidence rate23, while some other studies have found that high wind speed may increase the risk24. Such contradictions may result from differences in study areas and climatic conditions. A series of studies kept confirming that changes in climatic conditions may impact the incidence and transmission patterns of FBD outbreaks.

Whilst some researches on single factors or a specific kind of FBD have been carried out25,26, far too little attention has been paid to comprehensive meteorological impact on FBD outbreaks. It has been showed that the spatial and temporal patterns of the effects of climatic conditions on FBD outbreaks varied across different regions15. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the potential mechanisms between meteorological elements and FBD outbreaks, using a multi-year surveillance data reported by the FBD Surveillance Network combined with local meteorological conditions. In this paper, temperature, precipitation and wind speed were selected as representative elements to analyze the response of FBD outbreaks under different levels of exposure, thereby providing a scientific basis for further improving the design and implementation of public health sector interventions to address FBD.

Materials and methods

Study area and data collection

We choses Yantai city as the study region (Fig. 1), a coastal city in the northeastern part of the Shandong Peninsula, East China, with a permanent population of approximately 7.03 million. Yantai has established a surveillance network for FBD that encompassed all 14 counties and municipalities, covering 167 sentinel hospitals, over 1000 community health service stations, and village health offices. Based on this system, it was possible to effectively obtain the status of relevant diseases in the region. In the system, the FBD outbreaks are defined as the occurrence of two or more similar diseases caused by the ingestion of a certain food. And the data used in this study were FBD outbreaks from July 2014 to March 2024.

The meteorological data were collected from the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis data for the global climate and weather (ERA5) at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets. ERA5 can be applied in multiple fields, including climate research, weather analysis, climate model validation, and environmental monitoring27. In this paper, the 2 m-temperature, total precipitation, 10 m-u- and 10 m-v-component of wind speed, and other meteorological data were utilized. The dataset had a temporal resolution of 1 h and a spatial resolution of 0.25 degree. Subsequently, the dataset was processed into weekly data in accordance with the requirements of the assessment calculation. The weekly average method was employed for temperature and wind speed, while the cumulative method was applied for precipitation.

Study area. The left map was generated by Basemap (Version: 1.4.1, https://matplotlib.org/basemap/stable/users/introduction.html), and the right vector data was sourced from the National Geomatics Center of China through Tianditu (approval number GS(2024)0650, https://cloudcenter.tianditu.gov.cn/administrativeDivision).

Methods

Related studies have demonstrated that environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, and vegetation cover usually typically have a non-linear and lagged effect on FBD outbreaks26,28. Therefore, in this paper, the distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) was employed, which is a flexible modeling framework for exploring lagged effects. It has wide applications in many fields, including epidemiology, meteorology, and economic forecasting16,29,30. In the study, we took the Generalized Linear Models (GLM) as a framework and used DLNM to construct cross-basis functions for each meteorological factor. Then the exposure-response associations between FBD outbreaks and each element was explored. And the basic computational model adopted in this study can be written as:

In the Eq. (1), CB(x, lag) denoted the cross-basis function, which captured the effects of a specific exposure variable x across different lag times lag. And ⊗ represented the Kronecker product. For the horizontal feature dimension (B1), a natural cubic spline (NS) model was utilized, while a fourth-order polynomial model was employed for the vertical lag dimension (B2). In the Eq. (2), t represented the time index; y represented the count of FBD outbreaks weekly; α was the intercept (constant term), and x represented certain meteorological element, l was the lag, and L denoted the maximum lag. The function g() was used to eliminate seasonal and long-term trends and can be defined by a spline curve; z represented potential confounders, P was the total number of confounders, and the function v() was used to control the mutation effect of z. In this context, v() is specified as the NS, and its degree of freedom was set to 4. According to related research results26,31,32, the maximum lag length was set to 4 weeks (28 days). Meanwhile, we took the median value of each meteorological data as the baseline reference.

Disparate meteorological elements may be correlated with one another. In regression analysis, if elements with high linear or near-linear correlation were included in the confounding term, the multi-collinearity problem may be triggered. This problem might lead to more unstable estimation results and reduce the explanatory power of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Therefore, we adopt the variance inflation factor (VIF) to detect and measure multi-collinearity:

In the Eq. (3), R2 represented the coefficient of determination of variable j, which measured the degree of linear correlation with others. A larger value of the VIF indicated a stronger linear correlation. Based on research experience, we set a threshold value of 10, and stepwise regression was applied to reduce multi-collinearity in the model for establishing the optimal subset of features. That was, in a dataset composed of multiple variables, if there are variables with VIF exceeding the threshold, the variable with the largest VIF was removed each time until the condition was met. After iterative optimization, precipitation was retained as confounders in the temperature-lag model; temperature was retained as confounders in the precipitation-lag model; and precipitation was retained as confounders in the wind speed-lag model. The above VIF calculations were completed based on the “statsmodels” library in Python software (version 3.9).

In the subsequent part of this paper, we developed DLNMs for different meteorological factors and analyzed the response mechanism between each meteorological factor and FBD outbreaks individually. We used the median value as the reference value, that is, its relative risk (RR) is 1.0. The analysis was completed with the “dlnm” package in R software (version 3.6.3).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Yantai Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Since the aggregated data used in the study were from routine surveillance and did not involve personal information, informed consent for study participation was not required.

Results

Description of FBD outbreaks and meteorological factors

From July 2014 to March 2024, Yantai reported 1,263 FBD outbreaks, with a cumulative 5,715 illnesses, having a weekly average of 11.31. Among the identified causative agents, 41.73% were biological bacteria such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Salmonella, 27.44% were fungi and their toxins like muscarinic toxins, 22.93% were toxic plants and their toxins such as saponins and hemagglutinins, 4.89% were chemical factors like nitrites, 2.63% were toxic animals and their toxins such as histamine and river herring toxins, and 0.38% were biological viruses such as norovirus.

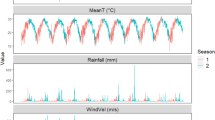

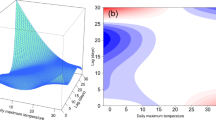

The time-series of diverse meteorological data and the distribution of the reported count of FBD outbreaks in Yantai was presented in Fig. 2. Evidently, temperature, precipitation, and wind speed had distinct seasonal cycles. Based on the data distribution (Fig. 3), temperature exhibited double-peak characteristics, while wind speed and precipitation showed single-peak and prominent trailing characteristics. Figure 3 indicated a certain correlation among the various types of data, and the correlation coefficients in the figure have passed the significance test at α = 0.01. This also indicated the necessity of conducting VIF screening before modeling.

Kernel density distribution (KDE) and correlation coefficients for various meteorological data. The univariate violin plots are on the diagonal, the KDE contours and Pearson correlation coefficients between two-by-two variables are on the lower left, and the upper right individually, where ** denotes highly significant (p < 0.01) and * denotes significant (p < 0.05). Note that logarithmic operations have been applied to FBD outbreaks in the figure to compress the data range for visualization.

Temperature - fbd outbreaks response

What is notable in Fig. 4 is that the cumulative disease risk increased as the mean weekly temperature rose. For an average weekly temperature of 24 °C and 4 °C, the 4-week cumulative lagged RR (Fig. 4e) was 0.25 (95% CI: 0.18–0.33) and 4.08 (95%CI: 3.05–5.44), respectively. However, this increasing trend was non-linear, with different evolutionary patterns in different lag time periods. At lag 0–1 weeks, the outbreak risk increased exponentially with rising exposure temperature. During lag 1–2 weeks, the increasing trend decreased significantly, and it reversed during lag 2–4 weeks. Judging from the overall cumulative RR within 0–4 weeks, when temperature was lower than the reference value (14.35 °C), the RR was less than 1.0, indicating an inhibitory-protective effect; when it was higher than the reference value, the RR continued to rise, meaning that the risk of FBD outbreaks increased rapidly and the temperature had a stimulatory-promotional effect.

Since excessively high or low temperature exposures led to opposite lagged effects, we selected 4 °C and 28 °C as representative values for low- and high-temperature exposures, respectively. The low-temperature effect had an immediate impact on FBD outbreaks in the population; strong low temperature significantly reduced the pathogenicity risk at lag 0 week (RR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.70). However, this effect gradually returned to normal as time passed, forming a local maximum around lag 2.6 weeks (RR: 1.29, 95% CI: 0.74–2.25). High- temperature exposure showed the opposite trend, with the RR reaching a maximum at lag 0 (RR: 2.82, 95% CI: 1.42–5.59), and the heat-induced risk declined rapidly as the lag time increased, reaching a local minimum again around lag 2.6 weeks (RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.45–1.36).

Exposure response between temperature (°C) and FBD outbreaks. The red lines are the mean RR, and the shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. (a-e) Cumulative RR for Lag 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 0–4 weeks. In subfigure e, the scatter points are used to indicate the selected observed values. (f-i) Effect of specific temperature or time lags on the RR.

Precipitation - FBD outbreaks response

A nonlinear relationship between precipitation and FBD outbreaks was also observed in Fig. 5. In contrast to the pathogenic effects of temperature, precipitation exhibited a similar cumulative RR evolutionary pattern over time. Greater precipitation amounts lead to a higher disease risk. The primary difference lies in the rate of increase, which was slower during lag 0–1 weeks and lag 3–4 weeks, and significantly accelerated during lag 1–3 weeks.

Compared with the 4 weeks cumulative RR (Fig. 5e) of median weekly precipitation (8 mm, RR = 1.0), extreme precipitation (155 mm) significantly increased the risk (RR: 126.65, 95% CI: 48.68–329.47.68.47). For the 4 weeks cumulative RR, fewer precipitation events (0 mm) led to a 23% reduction in RR (RR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.73–0.81). Taking the cumulative impact of 155 mm precipitation as an example, the cumulative RR at lags of 0–1, 1–2, 2–3 and 3–4 weeks were 4.97 (95% CI: 2.59–9.54), 10.67 (95% CI: 5.68–20.16), 11.82 (95% CI: 6.28–22.24) and 5.54 (95% CI: 2.79–11.01), respectively, with the lagged maximum of RR occurring during lag 1–3 weeks. Although extreme and sparse precipitation pose different outbreak risks in lag periods, they showed symmetrical characteristics in terms of the overall trend. Specifically, the overall trend of cumulative RR change showed a “low-high-low” or “high-low-high” pattern, peaking near lag 2 weeks at 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90–0.94) and 4.60 (95% CI: 3.05–6.93), respectively.

Exposure response between precipitation (mm) and FBD outbreaks. The red lines are the mean RR, and the shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. (a-e) Cumulative RR for Lag 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 0–4 weeks. In subfigure e, the scatter points are used to indicate the selected observed values. (f-i) Effect of specific precipitation or time lags on the RR.

Wind speed - FBD outbreaks response

The cumulative outbreak risk increased as the weekly mean wind speed increased (Fig. 6). For wind speeds of 3.5 m/s and 8.5 m/s, the 4-week cumulative lagged RR (Fig. 6e) were 3.09 (95% CI: 2.07–4.63) and 0.07 (95% CI: 0.03–0.18). Lower speed led to a higher disease risk, but the inhibitory effect of high wind speed diminished with cumulative time. When exploring the time-lagged effects of wind speed on FBD outbreaks, a remarkable pattern was observed: the cumulative pathogenic risk evolutionary showed high concordance across different lags, in contrast to the cumulative risk changes in temperature and precipitation. This phenomenon indicated a more homogeneous pathogenicity-risk distribution in the time dimension; that is, the wind speed effect was more stable and homogeneous in the short and long term.

Under high or low wind speed conditions, the disease risk evolution process was symmetrical. For example, under low wind speed (3.5 m/s), the RR exhibited a W-shaped evolution with an overall risk increase (RR > 1.0), and the maximum values were obtained near lag 0, lag 2, and lag 4 week, respectively. Under high wind speed (8.5 m/s), the evolution trend was M-shaped, and the overall risk was suppressed (RR < 1.0), with the minimum values also occurring near lag 0, lag 2, and lag 4 week. Despite the more convoluted evolution, the RR fluctuation ranges were relatively low under both wind speed conditions, further indicating that the wind speed induced risk was more stable in the time-lagged dimension.

Exposure response between wind speed (m/s) and FBD outbreaks. The red lines are the mean RR, and the shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. (a-e) Cumulative RR for Lag 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 0–4 weeks. In subfigure e, the scatter points are used to indicate the selected observed values. (f-i) Effect of specific wind speed or time lags on the RR.

Distribution of meteorological factors for different outbreak levels

FBD outbreaks can be grouped into high, medium, and low categories based on the percentile of the number of outbreaks (the percentage split was set at 33%, 66%), for the purpose of studying the distribution of factors at different incidence levels (Fig. 7). A significant stratification phenomenon was captured; that was, outbreaks exhibited hierarchical discrepancy among groups. Principally, higher temperature, more abundant precipitation, and lower wind speed generally corresponded to higher frequencies of FBD outbreaks. The above results highlighted the crucial role of meteorological conditions in FBD outbreaks, providing important early-warning signals for public health authorities to take precautionary measures under extreme risk conditions. Separately, there were significant characteristic in the response mechanisms of FBD outbreaks to different elements, which will be analyzed in the following sections.

Discussion

In exploring the effect of temperature on FBD outbreaks, this study noticed a significant nonlinear relationship, particularly regarding the difference between extreme high or low temperature effects. Taking the weekly average temperatures of 4 °C and 28 °C as extreme values, both of their lagged-risk evolution structures displayed a certain symmetry. Under low temperature, the lagged-risk structure presented a downhill parabola, while under high temperature, it took the form of a parabola in the opposite direction. In both antithetical conditions, the extremum point of the exposure effect was obtained near lag 2–3 weeks. Overall, the 0–4 weeks cumulative RR increased with rising temperature. Specifically, when ranging from − 5 °C to 10 °C, increases in temperature led to a relatively limited increase in the risk of FBD outbreaks; when temperature exceeded the reference value, the risk increased exponentially. This cumulative effect varied across lag periods to some extent, with the greatest cumulative effect occurring at 0–1 weeks, a significant decrease at 1–2 weeks, and a slight reversal of the pathogenic effect at 2–4 weeks. The temperature-induced pathogenicity risk showed complex multimodal dynamics over time, but its main pathogenic effect was concentrated in the lag 0–1 weeks.

This finding highlights the rapid response properties of temperature as a pathogenic factor, indicating that short-term temperature changes can significantly impact the intensity of FBD outbreaks within a week after exposure. One possible explanation is the saturation effect28. After that conditions were sufficient to trigger the growth, multiplication, and spread of wild mushrooms and microorganisms, there may be a spillover consequence of subsequent consecutive temperature effects. This observation was grounded in the fact that temperature changes can directly or indirectly affect the growth, spread, and host susceptibility of pathogens and vectors33,34. In the short term, elevated temperature can accelerate pathogen metabolism and reproduction rates. For instance, the replication cycles of bacteria and microorganisms causing diarrhea had been accelerated in warmer environments35, potentially leading to faster epidemic spreading. Unsuitable temperature may also reduce human resistance to disease9 and even reshape behavior patterns, such as increased consumption of water and reduced attention to hygiene36, thereby increasing the risk of infection and transmission. Additionally, temperature changes can affect food preservation37, facilitating pathogen accumulation and increasing the likelihood of FBD outbreaks.

Our findings are consistent with some previous studies. For example, a study on the relationship between average temperature and gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations in Spain and similarly found that the low or high temperature effects had a symmetrical structure and the same phenomenon of RR fluctuations with longer lag times16. A positive relationship between ambient temperature and FBD outbreaks was also consistent with the results of other studies at the week scale26,31. Given that this study focused on specific temperature ranges and analyzed the cumulative RR over different lag periods in detail, its findings may differ from other studies. In general, given the rapid-response nature of temperature-induced pathogenic risks, public health departments should be highly sensitive to temperature changes and implement more timely and precise public health interventions. Earlier warning mechanisms should be activated when unusual temperature events occur to reduce the temperature-induced disease burden.

In contrast to the immediate effect of heat-induced outbreaks, the pathogenic risk associated related to high precipitation moved more rearward. The results highlight that when assessing the impact of precipitation on FBD, the delayed characteristics and the complex interaction mechanisms should be fully considered. Firstly, the RR had a higher growth rate with increasing precipitation during lag 1–3 weeks. Meanwhile, extreme precipitation also maximized its threat to FBD outbreaks during this period. Subsequently, its pathogenicity decreased significantly within 1 week and after 3 weeks.

The mechanism of delayed effect may be closely associated with the characteristics of precipitation itself. Compared with temperature, although increased precipitation also affects disease transmission, for example, by creating more waterlogged areas for pathogens to colonize38, it may not be as responsive as temperature because temperature can directly stimulate pathogen metabolism and reproduction. Moreover, excessive precipitation may trigger secondary natural disasters such as flooding. These disasters can temporarily disrupt human activities by reducing movement, thereby decreasing the short-term risk. However, this temporary dampening effect cannot fully counteract the long-term impact of precipitation. In the long term, excessive precipitation may cause an increase in bacterial concentrations and turbidity in rivers, thus deteriorating water quality39,40. Meanwhile, large amounts of standing water and damaged infrastructure may provide more favorable conditions for microbial colonization and disease transmission.

When compared with existing studies, a similar finding has been reported in a case study of FBD in Singapore, where Salmonella infection cases increased 2 weeks after increased precipitation but decreased after 5 weeks25. Additionally, a study on Campylobacter incidence in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden also found a link with precipitation in the previous week13. These consistencies across different regions and pathogens reinforce the generalizability of the relationship between precipitation and FBD outbreaks. However, differences may exist in specific details due to variations in local environmental conditions, pathogen types, and study methodologies.

The results of this study revealed a negative correlation between wind speed and FBD outbreaks. The risk was significantly higher under low wind speed. This may be because low wind speeds are more conducive to the localized accumulation of microorganisms and pollutants, thereby increasing the likelihood of transmission. Moreover, the RR had some fluctuations during different lag periods, but the overall effects were similar, indicating that wind speed had an analogous influence pattern in the lag time dimension. One possible explanation is that not all foodborne pathogens can be airborne or form spores. Although viable foodborne microorganisms have been detected in air samples, the pathogenicity and transmission distance of these pathogens remain uncertain41.

Wind speed is a crucial factor influencing the spread of FBD, since it can modulate the dynamics of different vectors and pathogens42. The mechanism connecting wind speed and disease transmission is complex. One manifestation is dilution: faster wind speeds accelerate air movement, diluting the pathogen concentration, and theoretically reducing the chances of pathogen exposure43. Another manifestation is the accelerated transmission effect: suitable wind speeds can simultaneously facilitate the large-range transmission of pathogens, accelerating the spread rate of foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio, and other bacterial agents across spatial scales41. For example, pathogenic bacteria have been detected in the air near landfills, and farms nearby may be contaminated. Additionally, wind speed modulates environmental variables like carbon dioxide and relative humidity42, which are important factors in analyzing disease spread.

Based on aforementioned reversed effects, existing studies have found various relationships between wind speed and diseases, such as inverted U-shape, positive or negative correlation, or even uncorrelated41,44,45. Studies on the effect of wind speed on FBD outbreaks are relatively under-developed. Our finding of a negative correlation was different from some of the previous results24. The differences may be due to differences in study areas, pathogen types, and detection methods. This indicates that when assessing the impact of wind speed, it is necessary to integrate multiple factors such as specific regions, climates, and population characteristics. Relying solely on a single factor analysis result may yield unreliable conclusions.

Conclusion

The research utilized DLNM to combine meteorological factors with FBD outbreaks to uncover potential correlations. The results demonstrated significant nonlinear associations between meteorological conditions (such as temperature, precipitation, and wind speed) and FBD outbreaks. The lagged exposure-response patterns differed among these various meteorological elements, posing substantial challenges for public health interventions. Specifically, higher temperature, greater precipitation, and lower wind speed generally indicated a higher risk of FBD outbreaks. Considering the observed trends of climate change and extreme weather events, understanding the relationship between meteorological conditions and FBD outbreaks holds practical significance. The findings here offer insights into more comprehensively assessing the FBD outbreaks risk, and they also reiterate the importance of the early warning, prevention, and control measures implemented by public health authorities. For example, by establishing a continuous monitoring system for meteorological and environmental conditions, public health departments can release timely warning information to guide all aspects of food handling and storage, thus reducing the risk of FBD outbreaks.

The main weakness of this study was the insufficient consideration of fully confounding factors. The causative factors of FBD are complex and multifaceted, affected by multiple factors such as geographic location, population distribution, age structure, food culture, and customs15,20. Further experimental investigations are required to estimate more meteorological and environmental elements, such as humidity, evapotranspiration, sunshine duration, and vegetation index, which have been demonstrated to impact disease burden28,46. In addition, this research focuses on the overall analysis of the Yantai region. Research on districts and counties at a smaller observational scale and analyses by categories of foodborne pathogens will facilitate a better understanding of the mechanisms of FBD outbreaks.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are generally not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kumar, Y., Kaur, I. & Mishra, S. Foodborne disease Symptoms, Diagnostics, and predictions using artificial Intelligence-Based learning approaches: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 31, 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-023-09991-0 (2024).

WHO. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne diseases burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015, (2015). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/199350/9789241565165_eng.pdf

Finger, J. A. F. F., Baroni, W. S. G. V., Maffei, D. F., Bastos, D. H. M. & Pinto, U. M. Overview of foodborne disease outbreaks in Brazil from 2000 to 2018. Foods 8, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8100434 (2019).

Jaffee, S. H., Unnevehr, S., Grace, L. & Cassou, D. Emilie. The Safe Food Imperative: Accelerating Progress in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, (2019). https://hdl.handle.net/10986/30568

Smith, B. A. & Fazil, A. How will climate change impact microbial foodborne disease in canada? Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 45, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v45i04a05 (2019).

Semenza, J. C. & Paz, S. Climate change and infectious disease in europe: Impact, projection and adaptation. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 9, 100230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100230 (2021).

Mora, C. et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 12, 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01426-1 (2022).

El-Fadel, M., Ghanimeh, S., Maroun, R. & Alameddine, I. Climate change and temperature rise: implications on food- and water-borne diseases. Sci. Total Environ. 437, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.07.041 (2012).

Liu, Q. et al. Changing rapid weather variability increases influenza epidemic risk in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab70bc (2020).

Leigh, J. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Burkart, K. et al. Projecting global mortality due to non-optimal temperature from 2020 to 2100: a global burden of disease forecasting study. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3723614 (2020).

Djennad, A. et al. Seasonality and the effects of weather on Campylobacter infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 19(1), 255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3840-7 (2019).

Kuhn, K. G. et al. Campylobacter infections expected to increase due to climate change in Northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 10, 13874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70593-y (2020).

Akil, L., Ahmad, H. A. & Reddy, R. S. Effects of climate change on Salmonella infections. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 11, 974–980. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2014.1802 (2014).

Lal, A., Fearnley, E. & Wilford, E. Local weather, flooding history and childhood diarrhoea caused by the parasite Cryptosporidium spp.: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 674, 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.365 (2019).

Morral-Puigmal, C., Martínez-Solanas, È., Villanueva, C. M. & Basagaña, X. Weather and Gastrointestinal disease in spain: A retrospective time series regression study. Environ. Int. 121, 649–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.003 (2018).

Squire, S. A. & Ryan, U. M. Cryptosporidium and giardia in africa: current and future challenges. Parasit. Vectors 10 (1), 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2111-y (2017).

Khan, S. J. et al. Extreme weather events: should drinking water quality management systems adapt to changing risk profiles? Water Res. 85, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.08.018 (2015).

Morgado, M. E. et al. Climate change, extreme events, and increased risk of salmonellosis: foodborne diseases active surveillance network (FoodNet), 2004–2014. Environ. Health. 20, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-021-00787-y (2021).

Lake, I. R. Food-borne disease and climate change in the united Kingdom. Environ. Health. 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0327-0 (2017).

Lake, I. R., Barker, G. C. & Climate Change Foodborne pathogens and illness in Higher-Income countries. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 5, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0189-9 (2018).

Antunes, P., Novais, C. & Peixe, L. Food-to-Humans bacterial transmission. Microbiol. Spectr. 8 https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.MTBP-0019-2016 (2020).

Liang, D. et al. Global incidence of diarrheal Diseases-An update using an interpretable predictive model based on XGBoost and SHAP: A systematic analysis. Nutrients 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183217 (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. Meteorological change and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome epidemic in China, 2004–2018. Sci. Rep. 12, 20037. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23945-9 (2022).

Aik, J. et al. Climate variability and salmonellosis in Singapore – A time series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 639, 1261–1267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.254 (2018).

Lal, A., Hales, S., Kirk, M., Baker, M. G. & French, N. P. Spatial and Temporal variation in the association between temperature and salmonellosis in NZ. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 40, 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12413 (2016).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present, (2023). https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview

Okiring, J. et al. Associations between environmental covariates and Temporal changes in malaria incidence in high transmission settings of uganda: a distributed lag nonlinear analysis. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1962. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11949-5 (2021).

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Kenward, M. G. Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat. Med. 29, 2224–2234. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3940 (2010).

Wang, Q., Chen, Z., Huang, W., Kou, B. & Li, J. Short-Term Effect of Moderate Level Air Pollution on Outpatient Visits for Multiple Clinic Departments: A Time-Series Analysis in Xi’an China. Toxics 11, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11020166

Charron, D. F., Holt, J. D. & Maarouf, A. R. A time series analysis of the relationship of ambient temperature and common bacterial enteric infections in two Canadian provinces. Int. J. Biometeorol. 50, 385–391 (2006).

Gao, Y. et al. Climate factors driven typhus group rickettsiosis incidence dynamics in Xishuangbanna Dai autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province in China, 2005–2017. Environ. Health. 19, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0558-3 (2020).

El-Sayed, A. & Kamel, M. Climatic changes and their role in emergence and re-emergence of diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 27, 22336–22352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08896-w (2020).

Checkley, W., Epstein, L. D., Gilman, R. H., Cabrera, L. & Black, R. E. Effects of acute diarrhea on linear growth in Peruvian children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf179 (2003).

Semenza, J. C. et al. Knowledge mapping for climate change and Food- and waterborne diseases. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 378–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2010.518520 (2012).

Chou, W. C. et al. Modeling the impact of climate variability on diarrhea-associated diseases in Taiwan (1996–2007). Sci. Total Environ. 409, 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.09.001 (2010).

Concellón, A., Añón, M. C. & Chaves, A. R. Effect of low temperature storage on physical and physiological characteristics of eggplant fruit (Solanum melongena L). LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 40, 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2006.02.004 (2007).

Dayrit, J. F., Bintanjoyo, L., Andersen, L. K. & Davis, M. D. P. Impact of climate change on dermatological conditions related to flooding: update from the international society of dermatology climate change committee. Int. J. Dermatol. 57, 901–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13901 (2018).

Tornevi, A., Bergstedt, O. & Forsberg, B. Precipitation effects on microbial pollution in a river: lag structures and seasonal effect modification. PloS One. 9, e98546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098546 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Bi, P. & Hiller, J. E. Climate variations and Salmonella infection in Australian subtropical and tropical regions. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.068 (2010).

Hellberg, R. S. & Chu, E. Effects of climate change on the persistence and dispersal of foodborne bacterial pathogens in the outdoor environment: A review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 42, 548–572. https://doi.org/10.3109/1040841x.2014.972335 (2016).

Ellwanger, J. H. & Chies, J. A. B. Wind: a neglected factor in the spread of infectious diseases. Lancet Planet. Health. 2, e475. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30238-9 (2018).

van Leuken, J. P. et al. Climate change effects on airborne pathogenic bioaerosol concentrations: a scenario analysis. Aerobiologia (Bologna). 32, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-016-9435-5 (2016).

Ali, Q., Raza, A., Saghir, S. & Khan, M. T. I. Impact of wind speed and air pollution on COVID-19 transmission in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (Tehran). 18, 1287–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03219-z (2021).

Ward, M. P., Xiao, S. & Zhang, Z. Humidity is a consistent Climatic factor contributing to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 67, 3069–3074. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13766 (2020).

Awad, D. A., Masoud, H. A. & Hamad, A. Climate changes and food-borne pathogens: the impact on human health and mitigation strategy. Clim. Change. 177, 92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03748-9 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by Medical and Health Science and Technology Projects in Shandong Province, Grant number 202312020264; Scientific Research Project of Shandong Provincial School Health Association, Grant number JKZX2023211; Yantai Social Science Planning Project, Grant number YTSK2025-695; 2025 Natural Resources Satellite Remote Sensing Technology System Construction and Application Demonstration Project, Grant number 202501003, and Yantai Key Laboratory of Quality Safety Control and Deep Processing of Seafood Products Open Fund, Grant number QSCDP202307.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., Z.Y. and X.F.: project design., G.W., Y.Z. and G.S.: data collection and management. F.D. and J.W.: data processing and analysis. Y.C. and Z.Y.: manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Yuan, Z., Wang, G. et al. Nonlinear effects of meteorological factors on foodborne disease outbreaks in yantai from 2014 to 2024. Sci Rep 15, 39309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22928-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22928-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spatiotemporal drivers of foodborne disease seasonality pattern in a coastal city of China

BMC Public Health (2025)