Abstract

It is of great significance to understand and master the influence of stiffness parameters on the projectile configuration structure for the design and evaluation of configuration optimisation. In order to obtain the response characteristics of the configuration structure under dynamic load, this paper constructs a theoretical model of the projectile configuration structure reflecting the basic connection characteristics of the charge and the shell based on the concentrated mass method according to the typical characteristics of the actual projectile structure; numerically solves the problem by using the 4th Runge-Kutta method; analyses the response law of the configuration structure under the change of shell stiffness or contact stiffness. The results show that: there is a “small load, big response” rule of change in the projectile structure; when the shell stiffness reaches a certain amplitude, both the response of the charge and the shell tends to flatten, then raise the shell stiffness on the response of the charge structure does not contribute much; contact stiffness is bigger, the response becomes bigger; the increase of the cladding between the charge and the shell, the charge response can be achieved to reduce. If the cladding layer is added between the charge and the shell, the goal of reducing the response of the charge can be achieved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The structure of a projectile is usually a multi-body system consisting of parts such as the shell, the partition and the charge. In the penetration process of a projectile, the relative motion of various components generates complex dynamic behaviours such as clearances and collisions. The in-depth study of the nonlinear response of the multi-body components in the projectile due to their interaction is of great significance to the structural design and safety assessment of the projectile. This not only helps to understand the dynamic response law of the projectile in the process of penetration, but also provides theoretical support for the optimisation of the projectile structure, puts forward the loading performance index that is more in line with the actual demand, and provides important reference for the improvement of the design of the projectile. The projectile structure is a complex multi-parameter system, and its dynamic response is affected by various factors such as stiffness, damping, mass, excitation load, clearance and boundary conditions of each component1,2,3. Among them, the stiffness is one of the important physical properties of the projectile, and it is also the main parameter of the projectile design, which will have an important impact on the mechanical behaviour and performance of the projectile.

Scholars at home and abroad have carried out in-depth and extensive research in this area. Qi Zhang et al.4 studied the sensitivity of the projectile structure modes to its stiffness distribution, and on this basis for the case of multiple connecting surfaces were analysed, and the results of the study have certain guiding significance for the design and location arrangement of projectile connecting parts. Lei Yang et al.5 used the projectile stiffness test to obtain the deformation data, and iteratively corrected the connection stiffness of the rocket section by combining the test data with the finite element numerical analysis. The analysis results show that the calculated values of the modified intrinsic properties are closer to the measured values of the test. Tongle Lu6 carried out an in-depth analysis of the static stiffness of the projectile wing launching mechanism in the clearance state, and based on the fractal geometry and contact stress theory, modelled and analysed the dynamic stiffness of the mechanism in the clearanceless state, so as to study the relationship between the locking force and the support stiffness. Mingyi Wang et al.7 calculated the heat flow density distribution on the surface of a high-speed flying projectile using Lees’ formula and performed finite element simulations of the modal characteristics. They explored the effects of temperature-induced material softening and thermal stresses on the structural stiffness. Zhiqiang Xu et al.8 analysed the structural force transfer paths based on the principle of static equivalent toughness and applied shape optimisation and free shape optimisation methods to achieve light-weighting of the structure by changing the local structure at the load-bearing location and replacing the high-strength steel with aluminium alloy. Shah et al.9 carried out experiments on granite samples impacted by projectiles with different stiffnesses, and found that the degree of granite damage was closely related to the projectile stiffness; the experimental results were compared with the numerical simulation results of finite element analysis, and found that the two were in good agreement, thus proving that the projectile stiffness is an important factor in the destruction of granite. Burton10 established a model for the dynamic characteristics of the projectile internal cavity, and found that the projectile hole stiffness has a decisive effect on the projectile motion. The results show that maintaining the chamber equivalent contact stiffness of the SLEKE projectile model can minimise the difference in lateral acceleration, which in turn reduces the risk of bursting when the projectile is chambered. Dursun11 carried out a detailed study of the variations in projectile recoil stiffness, support stiffness, muzzle velocity, front and rear chamber diameter manufacturing tolerances, and found that these parameters have a significant effect on the systemic performance and blast with significant effects. Wahrhaftig et al.12 used optimised shape functions in the Rayleigh method to determine the critical buckling load and fundamental natural frequency of non-prismatic reinforced concrete slender columns. The study considered a series of acceptable shape functions that describe the buckling mode shape and the fundamental natural frequency of the columns, and developed an optimisation strategy to obtain the optimal shape functions. Wahrhaftig et al.13 proposed that the concept of spring stiffness is no longer defined as a function induced by displacement but is instead determined by the forces acting on the system. This hypothesis was evaluated using the vibration theory of mechanical systems and validated through a simply supported beam model subjected to axial forces. Both experimental and numerical results demonstrated that the natural frequency of the beam remains constant, even when the system is under axial forces that tend to reduce its structural stiffness and consequently alter the system’s vibration frequency.

From the current research situation at home and abroad, scholars mostly carry out research work from the perspective of impact dynamics, and the research on the nonlinear response mechanism generated by the projectile structure in the process of penetration is very limited. This paper establishes a theoretical model that can be used to describe the multi-body interactions of the projectile configuration structure; based on the theoretical model, the influence law of stiffness on the local response of the projectile configuration structure is obtained by changing the main stiffness parameters of the model. It is of great significance to understand and master the influence of these parameters on the multi-body interaction of the projectile configuration for the design and evaluation optimisation.

Construction of theoretical model

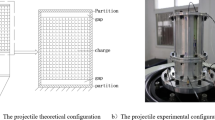

Mechanical vibration system with clearance and collision is a multi-parameter high-dimensional system, and the non-linearity and singularity caused by factors such as collision or impact make the system have strong nonlinear dynamics, but it is very difficult to comprehensively consider all the physical processes in the collision, so it is necessary to reasonably simplify the collision conditions and processes14. The projectile configuration structure for target penetration is mainly composed of the shell, charge and other auxiliary functional parts. The shell and charge are the main structural parts of the shell. The simplified configuration structure of the perojectile adopts a segmented design, simulating a two-layer cylinder shell structure, only the upper cylinder has a charge, and the lower cylinder has no charge. The outer part is composed of the cylinder and partition plate simulating the typical column characteristics. The material is aluminium; the inner part is filled with the column simulating the loading structure. Considering the clearance characteristics of the axial direction of the projectile, the two-layer cylinder containing the clearance loading of the configuration structure as the object, the use of concentrated mass method to establish an analytical model, as shown in Fig. 1.

The lower end of the shell in the initial state is the projectile constraint surface, as the action surface of the load applied. The bottom of the charge is connected with the shell in contact. There is a very small clearance b between the top of the charge and the shell. Assuming that in the process of multi-body motion, the clearance between the lower end of the charge and the shell is b1, and the clearance between the upper end of the charge and the shell is b2. The clearance under the initial state is b1 = 0 and b2 = b. There is a b = b1 + b2 in the process of vibration, when b1 > 0, the lower end of the charge has no contact with the shell; when b2 > 0, the upper end of the charge has no contact with the shell.

In nonlinear dynamical systems, a nonlinear square term usually refers to a term in the equation of motion that is proportional to the square of the displacement. Such square terms are important in describing certain physical processes because they capture the nonlinear behaviour of the system under specific conditions. The addition of a nonlinear square term before the velocity term is also intended to take into account the more nonlinear parameters of the actual model15. Based on the different states of motion between the charge and the shell, the equations of motion for the two-degree-of-freedom dynamics of the multi-body interaction of the charge structure of a typical projectile configuration are established by taking the shell and the charge as the objects, respectively.

Where: m1 is the total mass of the cylinder shells. m2 is the mass of charge in the upper barrel. k1 and c1 are the stiffness and damping coefficients of the shells respectively. k2 and c2 are the collision stiffness and damping coefficients of charge with the upper partition respectively. k3 and c3 are the collision stiffness and damping coefficients of charge with the lower partition respectively. x1 is the displacement of the entire simulated projectile. x2 is the displacement of charge. t is the time. \(\:{\text{f}}_{x}\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},{\dot{x}}_{1},{\dot{x}}_{2}\right)\)is the non-linear force at clearance b. \(\:F\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the excitation load applied to the projectile. \(\:\omega\:\) is the load frequency. \(\:{\upepsilon\:}\) and\(\:{\upsigma\:}\)are nonlinear damping coefficients that can be obtained experimentally or by combining relevant experience.

For the above model, the initial values of the design parameters: k1 = 2.9 × 109N/m, \(\:\:{\text{c}}_{1}=0.002\text{N}/(\text{m}/\text{s})\), \(\:{\text{m}}_{1}=4.85\text{k}\text{g}\), \(\:{\text{m}}_{2}=3.5\text{k}\text{g}\), b=0.01 mm, \(\:{\text{k}}_{2}\)=\(\:{\text{k}}_{3}\)=2.1 × 109N/m, \(\:{\text{c}}_{2}={\text{c}}_{3}=0.48{\text{k}}_{3}{\updelta\:}\), \(\:{\upepsilon\:}=1.02\), \(\:{\upsigma\:}=1.03\), \(\:\text{a}=2\text{g}\), \(\:{\upomega\:}=1544\text{H}\text{z}\). In order to ensure the analysis of the sensitivity of each parameter of the configuration structure, the calculations are carried out using the initial value parameters described above.

The calculation process starts with a normalisation process to convert the data to a uniform scale of displacement, which simplifies the subsequent calculation process. Especially when several variables with different scales or units are involved, the normalised equations are more conducive to numerical solution and programming implementation. Based on the normalised equations of motion, the 4th order Runge-Kutta method is used to discretely solve the established Eqs.16,17,18.

As can be seen through Fig. 2, the theoretical model calculation results due to the response of the charge in the time domain of the first part of the stage is not fully excited to a certain time before being excited and converge to the steady state. In this paper, we take the time domain data after the response tends to the steady state in the later analysis and calculation, and all the analysed time takes the value range of 200ms-300ms.

Influence of stiffness on the structural response of the projectile

Influence of shell stiffness on the structural response of the configuration structure

Keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged, only the value of the shell stiffness k1 is changed. The initial value of k1 is set to 2.9 × 109N/m because the shell material is selected as aluminum alloy. The other two sets of data are obtained by multiplying or dividing 2.9 × 109N/m by a factor of 2, aiming to analyze how the projectile’s response changes within a partial data range when k1 varies, thereby identifying certain patterns. Based on the initial value of k1 = 2.9 × 109N/m, k1 = 1.45 × 109N/m and k1 = 5.8 × 109N/m are considered respectively, and the changes in the response of the shell and charge part of the configuration structure under three different working conditions are calculated. The obtained displacement and acceleration time response of the shell part of the configuration structure under the three operating conditions are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The displacement and acceleration time response of the charge part are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

It can be seen from Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6:

(1) In the case of other parameter conditions remain unchanged, in the given three shell stiffness conditions, with the increase of shell stiffness k1, the displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge are reduced; the smaller the stiffness, the more obvious displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge are amplified with time;

(2) Comparing the three working conditions, it can be seen that in the shell configuration structure, the shell stiffness is too low to induce the response amplification of the shell and charge parts, and when the stiffness reaches a certain value, the amplification of the shell and charge response can be alleviated.

The values of the shell acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration at different shell stiffnesses in Fig. 4. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under different shell stiffnesses are collated, as shown in Table 1. The values of the charge acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration under different shell stiffnesses in Fig. 6. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under different shell stiffnesses are collated, as shown in Table 2. From Tables 1 and 2, it can be seen that, due to the nonlinear effect brought about by the clearance contact between the charge and the shell under different shell stiffness conditions, the magnification of the response, as well as the amplitude of the response of the shell and the charge, all show nonlinear variation characteristics.

From Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10, it can be seen that keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged and only changing the value of the shell stiffness k1. The values of k1 are considered respectively 0.725 × 109N/m, 1.45 × 109N/m, 2.9 × 109N/m, 5.8 × 109N/m, 8.7 × 109N/m, 11.6 × 109N/m, 14.5 × 109N/m, 14.5 × 109N/m, 17.4 × 109N/m, to calculate the change in displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge for the configuration structure. Under the given various shell stiffness conditions, the overall trend of the displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge becomes smaller with the increase of the shell stiffness k1. The smaller the stiffness is, the more obvious the amplification of the displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge is. Therefore, from the perspective of engineering applications, in order to reduce the response amplification phenomenon of the configuration structure, to avoid the occurrence of early ignition, early detonation, improve the shell stiffness of the projectile is an effective way. When the shell stiffness reaches a certain magnitude, both the charge and the shell response tends to flatten out, i.e., and then enhance the shell stiffness of the response of the charge structure is not much to contribute to the response.

Influence of contact stiffness on the response of the configuration structure

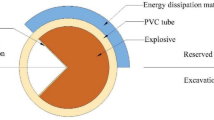

Keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged, only the value of the charge stiffness k2 is changed. The initial value of k2 is set to 2.1 × 109N/m because the energetic material selected is a polymer-bonded explosive (PBX) simulant material (designated as M-material). This M-material is a non-detonating safety analog formulated to replicate actual PBX compositions, fabricated by compacting surrogate particles with binders. Its microstructure, density, modulus, strength, and other mechanical properties closely match those of real explosives while eliminating explosion risks, making it a commonly used explosive substitute in experiments. The other two datasets are generated by multiplying and dividing 2.1 × 109 by a factor of 2 respectively, enabling analysis of projectile response variations within specific parameter ranges to identify underlying patterns when k2 is modified. Based on the initial value of k2 = 2.1 × 109N/m, k2 = 1.05 × 109N/m and k2 = 4.2 × 109N/m are considered respectively, and the changes of the responses of the shell and charge parts of the configuration structure are calculated for three different working conditions. The obtained displacement and acceleration time response of the shell part under the three operating conditions are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. The displacement and acceleration time response of the charge part are shown in Figs. 13 and 14.

It can be seen from Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14:

(1) When other parameters remain unchanged, in the given three contact stiffness parameter variation range, with the charge and shell contact stiffness k2 increases, the displacement and acceleration response of the shell part also becomes larger, which is different from the previous shell stiffness k1 influence change rule;

(2) When other parameters remain unchanged, in the given three contact stiffness parameter change range, with the contact stiffness k2 increase, the displacement and acceleration response of the charge part of the larger, which is different from the previous shell stiffness k1 influence change rule;

(3) Comparing the three working conditions, it can be seen that in the configuration structure, the lower contact stiffness of the shell and charge part can inhibit the amplification of the response of the charge part to a certain extent; When the contact stiffness increases to a certain extent, the amplification of the charge response will be more obvious.

The values of the shell acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration at different contact stiffnesses between the charge and the shell in Fig. 12. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under the contact stiffness between different charges and the shell are collated, as shown in Table 3. From Fig. 14 the amplitude of the charge acceleration under the contact stiffness between different charges and the shell can be obtained from the value of the charge acceleration response. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under the contact stiffness between different charges and shells are collated, as shown in Table 4. From Tables 3 and 4, it can be seen that, due to the nonlinear effect brought about by the clearance contact between the charge and the shell under different conditions of contact stiffness between the charge and the shell. The magnification of the response as well as the amplitude of the response of the shell and the charge show nonlinear variation characteristics.

From Figs. 15, 16, 17 and 18, it can be seen that keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged and only changing the value of the contact stiffness k2. The values of k2 are considered respectively 0.525 × 109N/m, 1.05 × 109N/m, 2.1 × 109N/m, 4.2 × 109N/m, 6.3 × 109N/m, 8.4 × 109N/m, 10.5 × 109N/m, 10.5 × 109N/m, 12.6 × 109N/m, to calculate the change in displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge of the configuration structure. The displacement and acceleration responses of the shell and charge sections become larger as the contact stiffness k2 increases for the given multiple contact stiffness conditions. The contact stiffness responds to the intensity of the collision between the charge and the shell, when the degree of collision is small, the response is small; but when the degree of collision increases, the response becomes large. If the cladding layer is added between the charge and the shell, the goal of reducing the charge response can be achieved. Therefore, from the perspective of engineering applications, in order to reduce the response amplification phenomenon of the configuration structure to avoid the occurrence of early ignition, early detonation, reduce the contact stiffness of the shell and charge is an effective way.

Numerical simulations

Finite element model

Based on the finite element method, the charge clearance b is set to 0.4 mm. A linear analysis model of a typical projectile is established, as shown in Fig. 1919. The simulated projectile of the simplified configuration structure adopts a segmented shell design. The exterior is composed of a shell and partition that simulate the characteristics of a typical column. The interior is filled by a column that simulates the charge structure. The simulated shell has an overall length of 370 mm, the diameter of 120 mm, barrel thickness of 5 mm. The charge has a length of 199 mm, the diameter of 110 mm. The partition is steel. The barrel is aluminium. The column is charge. The present constitutive model uses a linear elastic model, without considering contact effects, so that ρ, E and υ denote density, modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio respectively. Initial partition parameters: ρ = 7.85 g/cm3, E = 200GPa, υ = 0.3. Initial barrel parameters: ρ = 2.7 g/cm3, E = 70GPa, υ = 0.3. Initial charge parameters: ρ = 1.85 g/cm3, E = 10GPa, υ = 0.3. Calculated with finite element software, the whole projectile is divided into 68,821 hexahedral meshes, as shown in Fig. 2019.

Verification of results

Influence of shell stiffness on the structural response of the configuration structure

Keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged, only the value of the shell stiffness k1 is changed. The initial value of k1 is set to 2.9 × 109N/m because the shell material is selected as aluminum alloy. The other two sets of data are obtained by multiplying or dividing 2.9 × 109N/m by a factor of 2, aiming to analyze how the projectile’s response changes within a partial data range when k1 varies, thereby identifying certain patterns. Based on the initial value of k1 = 2.9 × 109N/m, k1 = 1.45 × 109N/m and k1 = 5.8 × 109N/m are considered respectively, and the changes in the response of the shell and charge part of the configuration structure under three different working conditions are calculated. The obtained acceleration time response of the shell part of the configuration structure under the three operating conditions are shown in Fig. 21. The acceleration time response of the charge part are shown in Fig. 22.

It can be seen from Figs. 21 and 22 :

(1) In the case of other parameter conditions remain unchanged, in the given three shell stiffness conditions, with the increase of shell stiffness k1, the displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge are reduced; the smaller the stiffness, the more obvious displacement and acceleration response of the shell and charge are amplified with time;

(2) Comparing the three working conditions, it can be seen that in the shell configuration structure, the shell stiffness is too low to induce the response amplification of the shell and charge parts, and when the stiffness reaches a certain value, the amplification of the shell and charge response can be alleviated.

The values of the shell acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration at different shell stiffnesses in Fig. 21. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under different shell stiffnesses are collated, as shown in Table 5. The values of the charge acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration under different shell stiffnesses in Fig. 22. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under different shell stiffnesses are collated, as shown in Table 6. From Tables 5 and 6, it can be seen that, due to the nonlinear effect brought about by the clearance contact between the charge and the shell under different shell stiffness conditions, the magnification of the response, as well as the amplitude of the response of the shell and the charge, all show nonlinear variation characteristics.

Influence of contact stiffness on the response of the configuration structure

Keeping the other parameters of the configuration structure unchanged, only the value of the charge stiffness k2 is changed. The initial value of k2 is set to 2.1 × 109N/m because the energetic material selected is a polymer-bonded explosive (PBX) simulant material (designated as M-material). This M-material is a non-detonating safety analog formulated to replicate actual PBX compositions, fabricated by compacting surrogate particles with binders. Its microstructure, density, modulus, strength, and other mechanical properties closely match those of real explosives while eliminating explosion risks, making it a commonly used explosive substitute in experiments. The other two datasets are generated by multiplying and dividing 2.1 × 109 by a factor of 2 respectively, enabling analysis of projectile response variations within specific parameter ranges to identify underlying patterns when k2 is modified. Based on the initial value of k2 = 2.1 × 109N/m, k2 = 1.05 × 109N/m and k2 = 4.2 × 109N/m are considered respectively, and the changes of the responses of the shell and charge parts of the configuration structure are calculated for three different working conditions. The obtained acceleration time response of the shell part under the three operating conditions are shown in Fig. 23. The acceleration time response of the charge part are shown in Fig. 24.

It can be seen from Figs. 23 and 24:

(1) When other parameters remain unchanged, in the given three contact stiffness parameter variation range, with the charge and shell contact stiffness k2 increases, the displacement and acceleration response of the shell part also becomes larger, which is different from the previous shell stiffness k1 influence change rule;

(2) When other parameters remain unchanged, in the given three contact stiffness parameter change range, with the contact stiffness k2 increase, the displacement and acceleration response of the charge part of the larger, which is different from the previous shell stiffness k1 influence change rule;

(3) Comparing the three working conditions, it can be seen that in the configuration structure, the lower contact stiffness of the shell and charge part can inhibit the amplification of the response of the charge part to a certain extent; When the contact stiffness increases to a certain extent, the amplification of the charge response will be more obvious.

The values of the shell acceleration response can be obtained from the amplitude of the charge acceleration at different contact stiffnesses between the charge and the shell in Fig. 23. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under the contact stiffness between different charges and the shell are collated, as shown in Table 7. From Fig. 24 the amplitude of the charge acceleration under the contact stiffness between different charges and the shell can be obtained from the value of the charge acceleration response. The peak value and magnification of the acceleration response under the contact stiffness between different charges and shells are collated, as shown in Table 8. From Tables 7 and 8, it can be seen that, due to the nonlinear effect brought about by the clearance contact between the charge and the shell under different conditions of contact stiffness between the charge and the shell. The magnification of the response as well as the amplitude of the response of the shell and the charge show nonlinear variation characteristics.

Conclusions

The relevant research results in this paper show that the theoretical model of the configuration structure established can better simulate and reveal the phenomenon of charge response amplification due to nonlinear factors such as clearance and collision during the interaction between the shell and the charge, which provides a research idea different from that in the field of impact dynamics for the study of the kinetic behaviour of the projectile penetrating a multilayer target. In the case of a typical projectile configuration structure other parameters are unchanged, the shell stiffness, contact stiffness changes on the shell and charge components of the response changes in different laws:

-

(1)

With the increase of shell stiffness, shell and charge displacement and acceleration response will decrease; with the increase of contact stiffness of charge and shell, shell displacement and acceleration response will increase;

-

(2)

As the contact stiffness of the charge and shell increases, both the charge displacement and acceleration response increase.

-

(3)

Due to the nonlinear effect brought about by the clearance contact between the charge and the shell, the response amplification as well as the response amplitude of the shell and the charge show nonlinear change characteristics.

-

(4)

When the shell stiffness reaches a certain amplitude, both the response of the charge and the shell tends to flatten out, further increase the shell stiffness does not contribute much to the response of the charge.

-

(5)

The contact stiffness reacts to the intensity of the collision between the charge and the shell, when the degree of collision is small, the response is small; but when the degree of collision increases, the response becomes large. If the cladding layer is added between the charge and the shell, the goal of reducing the response of the charge can be achieved.

Geometric stiffness is crucial in the study, significantly influencing the dynamic response of the projectile structure. Increasing shell stiffness reduces displacement and acceleration responses, but the improvement plateaus beyond a certain value; reducing contact stiffness also mitigates responses, but with diminishing returns past a threshold.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the research is continuing but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xue, J. F. & Thesis, P. D. Research on the performance of projectile penetration and perforation into concrete target, Nanjing University of science & technology, Nanjing, (2016).

Liu, J. C. et al. Structural response of projectile in reverse ballistic Non-normal penetrating experiment. J. Acta Armamentarii. 40, 1797–1803. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1093.2019.09.005 (2019).

Zheng, Z. Y. et al. Analysis on structural strength, stability and vibration characteristics of slender projectile on penetrating into concrete. J. Shock Vib. 44, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.11809/bqzbfcxb2023.11.001 (2023).

Zhang, Q. & Liu., L. Research on influence of connection stiffness on projectile modes. J. J. Projectile Rockets Projectiles Guidance. 28, 38–40. https://doi.org/10.15892/j.cnki.djzdxb.2008.03.023 (2008).

L.Yang, Z. B. et al. Research on a rocket structure connection stiffness model updating method based on ABAQUS. J. Mach. 48, 43–48 (2021).

Lu, T. L. & Thesis, P. D. Design and analysis of ejection mechanism of projectile wing with high dynamic pressure and high stiffness, Nanjing University of science & technology, Nanjing, (2021).

Wang, M. Y. Study of changes in the structural stiffness of the projectile body due to the phenomenon of aerodynamic heating. J. Sci. Technol. Vis. 17 (3-4). https://doi.org/10.19694/j.cnki.issn2095-2457.2016.17.002 (2016).

Xu, Z. Q. et al. Projectile structure strength analysis and optimization design of aviation ammunition. J. Ordnance Mater. Sci. Eng. 44, 96–100. https://doi.org/10.14024/j.cnki.1004-244x.20210730.001 (2021).

Shah, H. Q. Hamdani.,The damage of unconfined granite edge due to the impact of varying stiffness projectiles. J. Int. J. Impact Eng. 59, 11–17 (2013).

L.W.Burton.,In-bore stiffness considerations for electromagnetic projectile armatures and boreriders, in Proceedings of 11. detonation symposium, Snowmass, CO, United States, 1998, Ed. by Los Alamos National Laboratory, pp. 43–46. (Los Alamos National Laboratory, United States, 1998).

Dursun, T. Effects of projectile and gun parameters on the dispersion. J. Def. Sci. J. 70, 166–174 (2020).

Wahrhaftig, A. D. M. et al. Buckling and free vibration analysis of non-prismatic columns using optimized shape functions and Rayleigh method. J. Eur. J. Mech. Solids. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2022.104543 (2022).

de Macêdo Wahrhaftig, A. et al. Control of the vibration of simply supported beams using springs with proportional stiffness to the axially applied force. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 10, 2163–2177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-022-00502-2 (2022).

Qian, W. C. Armour piercing mechanics. (Defence Industry Press, Beijing, 1984).

Ding, Z. S. & Ou, Y. B. Zhang.,Dynamic modeling and analysis of arresting net based on iumped mass method. J. J. Naval Univ. Eng. 35, 52–60 (2023).

Richard, L. B. Numerical analysis, (Electronic Industry Press, Beijing, 2022).

Timothy, S. Numerical analysis. (Machinery Industry Press, Beijing, 2014).

Nie, Y. F. & Feng, J. H. G.M.Che.,Principles of Numerical Analysis (Science, 2022).

J.Liang, X. H. et al. Response amplification study of the simulated projectile under typical boundary conditions. J. Mech. Solids. 59, 3132–3147 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no.11872059), Platform for wind turbine coupling research and innovation team (CXTD2023LX02), Domestic R&D and Manufacturing of Wind Turbine Couplings(QD2019A11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jun Liang. Xuanhua Fan. and Shifu Xiao wrote the main manuscript text. Liang Zhang and Deming Huang prepared experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, J., Fan, X., Xiao, S. et al. Study on the effect of stiffness parameter on response in dynamic modelling of the projectile. Sci Rep 15, 39478 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22963-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22963-7