Abstract

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) as a symptom of COVID-19 has received significant attention in research due to its high prevalence. While it is transient in the majority of individuals, post-COVID OD persists in a notable subset of patients even months to years after the acute infection. A deeper understanding of the underlying factors driving this phenomenon is essential. There is increasing evidence for an involvement of the central nervous system in this deficit. The objective of this study was to investigate the structural connectivity and integrity of white matter pathways in brain regions associated with olfactory processing using MRI with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in patients with persistent post-COVID OD. The study involved 61 patients, divided into two groups: 31 participants with post-COVID OD (PC-OlfDys) and 30 post-COVID normosmic controls (PC-N). For MRI analyses, a region of interest (ROI)-based approach and voxelwise statistical comparisons between the groups with age as a covariate was used. Fractional anisotropy (FA) in the left amygdala was higher in the PC-OlfDys than in the PC-N group, and radial diffusivity (RD) in the right amygdala was higher in the PC-OlfDys group than in PC-N. The PC-OlfDys group exhibited higher depression and anxiety scores, as measured by the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 questionnaire, respectively. This study shows that post-COVID OD is associated with significant changes in the myelination or axonal diameter of olfactory-related brain regions. As the amygdala, putamen and piriform cortex (all involved in olfactory function and emotional well-being) showed associations with depression and anxiety scores, we hypothesise that post-COVID OD and depression and anxiety are interrelated, although the direction of this relationship remains to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The olfactory aspect of COVID-19, often presented as reduced smell sensitivity (hyposmia) or complete loss of smell (anosmia), has received much attention in research1. While the acute symptoms of viral infection may subside after a few weeks for many individuals, a significant proportion continues to struggle with a range of persistent health issues including persistent olfactory dysfunction (OD) long after the initial infection has cleared2,3. Different terms for these long-term effects of COVID-19 have been established. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), post COVID-19 condition is defined as the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation4. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) differentiates between long COVID, which sums up all symptoms persisting after four weeks past infection, and post-COVID-19 syndrome, defined by persistence over 12 weeks5. Understanding the underlying factors driving this phenomenon is crucial to developing effective management strategies and providing appropriate support to those affected.

A recent article outlined the impact these persistent symptoms have on patients who are not hospitalised6. Since many of the symptoms of long COVID patients, including fatigue and OD, involve brain function, it is obvious to look for cerebral changes that might explain them. It has been well documented that limbic system alterations are associated with COVID-197. Research has shown reduction in recognition of emotional stimuli after 6–9 months post infection with COVID-198. Apart from limbic system involvement in COVID-19, numerous cerebral alterations have been reported. A recent study revealed gray matter reduction in thalamus, internal capsule, cerebellum, and brainstem as well as a OD9. In addition, the olfactory bulb, the first relay centre in the brain for olfactory perception, has often been shown to have a reduced volume in long COVID, although perhaps not as much as in OD of other etiologies10. Parosmia, a distorted odor perception, is common after COVID-19, and associated with reduced functional connectivity in key olfactory brain areas such as the primary olfactory cortex (piriform cortex and amygdala), and decision-making areas in the brain (prefrontal cortex)11. Given that there is significant cerebral change, it becomes relevant to examine changes in structural connectivity associated with post-COVID OD.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), an advanced MRI technique, offers a unique window into the structural connectivity and microstructural integrity of the brain’s white matter pathways12. By mapping the diffusion of water molecules along neural tracts, it is possible to discern subtle alterations in axonal organization, myelination, and overall connectivity, providing valuable insights into the neurological sequelae of COVID-19. In the context of post-COVID OD, diffusion imaging holds promise for uncovering the underlying neural correlates of persistent OD and related symptoms13,14. Preliminary findings from diffusion imaging studies have highlighted alterations in white matter integrity and connectivity patterns within olfactory circuits, mainly left amygdala, insula, and parahippocampal gyrus, among individuals with persistent OD post-COVID-1915. These alterations may reflect direct viral-induced damage, secondary inflammatory processes, or neuroplastic changes in response to sensory deprivation. Moreover, diffusion imaging offers a non-invasive means of tracking changes in brain structure and connectivity over time, enabling researchers to monitor the progression or resolution of neurobiological abnormalities in long COVID patients. Such longitudinal studies are essential for unravelling the trajectory of neurological recovery and identifying potential predictors of persistent OD and other neurological sequelae. Diffusion metrics, such as fractional anisotropy (FA) reflecting overall white matter integrity, mean diffusivity (MD) indicating tissue damage, and axial (AD) and radial diffusivity (RD) reflecting myelination strength and microstructural integrity, respectively, provide insight into microstructure integrity. However, a disadvantage of many of the studies that have been conducted to date is that they have examined very heterogeneous patient cohorts1,14. These studies included patients with mild courses, as well as those hospitalised or in intensive care units. This ultimately distorts the evaluations, making it impossible to determine whether the integrity of the white matter was affected by the SARS-CoV-2 infection or by complications arising from treatment. This calls into question the validity of some previous studies.

Our aim was to investigate if there are differences between two groups of people diagnosed with mild, non-hospitalised cases of COVID-19: a group experiencing ongoing olfactory dysfunction (OD), hereafter referred to as the post-COVID OD group (PC-OlfDys), and a control group consisting of individuals who have recovered, hereafter referred to as the post-COVID normosmic group (PC-N). The main question was how OD affects diffusion metrics and whether these alterations can elucidate the long-term effects of olfactory loss based on a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than complications in the treatment process. The specific hypothesis was that individuals in the PC-OlfDys group would show structural changes in areas previously implicated in reduced functional connectivity.

Methods

Patient demographics

This study included 61 participants who had participated in the interdisciplinary COVIDOM study at a university hospital on average 8.56 (± 2.34) months after their infection with SARS-CoV-2. The experiments were conducted according to the Helsinki declaration. COVIDOM aimed to investigate the long-term effects of COVID-19 and was conducted on behalf of the National Pandemic Cohort Network (NAPKON)16. The COVIDOM study protocol and procedures were approved by the local ethics committees (Kiel: D537/ 20; Würzburg: 236/20_z; Berlin: according to the coordinating study centre Kiel). Local data protection officers have been informed as required. All participants gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in NAPKON-POP COVIDOM-study. All participants had a PCR-confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2 at least 6 months ago and were at least 18 years old at inclusion. Exclusion criteria were claustrophobia, current pregnancy, and medical implants incompatible with MRI. During the initial visit and directly around the MRI assessment, olfactory function was assessed using the Sniffin’ Sticks test (Burghart Messtechnik GmbH, Holm, Germany) as described previously17. We used the n-butanol version with the wide step method to examine the threshold (T) and summed it up with the discrimination (D) and identification (I) scores for the Threshold-Discrimination-Identification (TDI) score18,19. To classify the outcome clinically, terms ‘normosmia’ and ‘dysomsia’ were used in line with the relevant literature19. For the PC-OlfDys group, 31 individuals were recruited, who had persistent OD after their infection with SARS-CoV-2, defined by a TDI score < 31. The PC-N control group consisted of 30 participants who had also been infected with SARS-CoV-2 but were normosmic, defined by a TDI-Score ≥ 31.

Clinical data

All participants completed extensive questionnaires covering demographic data, smoking status, general medical history, and the course of their acute COVID-19. In the questionnaires, the participants were asked to rate their sense of smell on a ten-point Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from 0 (= no sense of smell) to 10 (= extremely good sense of smell). They rated it retrospectively for the time before and during their infection with SARS-CoV-2, and at the time of the study, i.e. after their infection. Asked about changes in their olfaction, participants also selected answers to the question ‘Since my infection, I perceive odors…’: ‘…same as before.’, ‘…less intensively than before.’, ‘I don’t know’, and ‘…differently than before (changed quality of smell).’ The last option was interpreted as an indicator of parosmia. To examine neuropsychological changes after the infection, participants were also asked to complete the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression (PHQ-8) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) questionnaire. The PHQ-8 is a validated screening tool for severity of depressive symptoms with a score ranging from 0 to 2420. The cut-off values for mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depressive symptoms are ≥ 5, 10, 15, and 20. GAD-7 screens for severity of anxiety symptoms, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 21 with scores of ≥ 5, 10, and 15 as cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety21. At the onsite visit of the COVIDOM-study, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test (MoCA) was administered to test for cognitive impairment. It assesses different dimensions of cognitive functions resulting in a total score of up to 30 points. Scores ≥ 26 are considered normal22.

MRI protocol

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was carried out using a 3 Tesla MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Vida; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), employing a 32-channel receiver head coil for image data acquisition. DTI data was acquired using echo planar imaging with GRAPPA having the following parameters: TR (repetition time) = 13,200 ms, TE (echo time) = 101 ms, slice thickness = 1,6.mm, field of view (FoV) = 210 × 210, repetitions = 1, flip angle = 180°. Diffusion scans were obtained at b = 0 and b = 1000 s/mm2, utilising 30 diffusion directions. A 3D T1-MPRAGE sequence with iso voxel resolution (1 × 1 × 1) was also acquired with a TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.27 ms, having a distance factor of 50% and layer oversampling of 45.5%.

Tract based spatial statistics (TBSS)

Voxelwise statistical analysis of the FA data was carried out using the Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS)23 part of FMRIB software library (FSL)24. First, FA images were created by fitting a tensor model to the raw diffusion data using FSL diffusion toolkit (FDT), and then brain-extracted using brain extraction toolbox (BET)25. All subjects’ FA data were then aligned into a common space using the nonlinear registration tool FNIRT, which uses a b-spline representation of the registration warp field (Rueckert et al. 1999). Next, the mean FA image was created and thinned to create a mean FA skeleton, which represents the centres of all tracts common to the group. Each subject’s aligned FA data were then projected onto this skeleton, and the resulting data fed into voxelwise cross-subject statistics. The same procedure was repeated to obtain images for mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD). To compare the voxelwise statistics, we employed t-test with age as a variable. Further, ROI based analyses were run as previously described26. In addition, a few other ROI involved in olfaction were identified based on literature13, namely the amygdala, hippocampus, and thalamus. The reason for using specified ROIs is due to their role in olfaction, which has been well documented27,28. Recent articles have also used our previous work, specifically for defining primary olfactory regions29,30. We extracted the FA, MD, AD and RD values from each ROI using fslmeants, a FSL based utility tool (fslmeants -i all_FA.nii.gz -o ROI.txt -m ROI.nii.gz) and compared the values between two groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism (version 8 for Windows GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, www.graphpad.com) and IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 29.0.1.1 for Windows, IBM, 2023, www.ibm.com). Mean and standard deviation (± SD) were calculated for metric variables and inter-group comparisons were done using the Mann–Whitney U-test (non-parametric). Independent samples t-test was performed to compare FA, MD, RD and AD values from the ROI between cohorts. Whole-brain TBSS voxelwise analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using family-wise error (FWE) correction at p < 0.05. A two-tailed bivariate using Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis was further performed between diffusion values and questionnaires of interest, with multiple comparisons adjusted using Bonferroni correction where applicable. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics

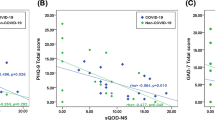

All participants were examined between April and October 2022 and study demographics are listed in Table 1. The participants in the PC-OlfDys group rated their sense of smell significantly lower during and after infection than the PC-N group (p = 0.007 and < 0.001, respectively). When asked about changes in their smell perception, 10 out of 26 persons (38%) in the PC-OlfDys group and 0 out of 28 (0%) in the PC-N group answered, ‘Since my infection, I perceive odors… differently than before (changed quality of smell)’, indicating parosmia. In the Sniffin’ Sticks test, as intended by the study design, the groups showed a significant difference for all three sub scores and the TDI (p < 0.001), with the PC-N group performing better (Table 2). The mean PHQ-8 score was 9 ± 5 in the PC-OlfDys group and 2 ± 2 in the PC-N group (p < 0.001). The mean GAD-7 score was 6 ± 5 in the PC-OlfDys group and 1 ± 2 in the PC-N group (p < 0.001, Fig. 1). The MoCA was not significantly different between the groups (27 ± 3 in the PC-OlfDys group vs. 27 ± 2 in the PC-N group, p = 0.5).

TBSS analysis

Whole-brain TBSS did not show significant group differences after FWE correction (p < 0.05) ran using randomise with 5000 permutations.

ROI analysis

Independent samples t-test showed that FA values in the left amygdala were significantly higher in PC-OlfDys than in PC-N group (mean ± SD, 0.25 ± 0.02 vs. 0.24 ± 0.01, F = 5.417; p = 0.014) and RD values in the right amygdala were higher in PC-OlfDys than in PC-N group (7.1 × 10− 4 ± 3.6 × 10− 4 vs. 6.8 × 10− 4 ± 4.7 × 10− 4, F = 1.152, p = 0.03) (Fig. 2). All other ROI did not differ significantly in any of the diffusion values.

Correlations

A bivariate correlation analysis was performed for each group with all diffusion values (FA, MD, RD and AD) from each ROI and PHQ-8, GAD-7, MoCA, and TDI and sub scores.

Olfactory function

In the PC-OlfDys group, the TDI score did not correlate with any of the diffusion values. However, in the anterior piriform cortex, the identification score was negatively correlated with AD values (r = − 0.367, p = 0.04). In the left amygdala, the discrimination score was negatively correlated with MD (r = − 0.389, p = 0.03) and RD values (r = − 0.491, p = 0.005). In the right putamen, the threshold score was negatively correlated with RD values (r = 0.375, p = 0.03).

Looking at the PC-N group, in the right putamen, the TDI score was positively correlated with MD values (r = 0.432, p = 0.01). Additionally, in the left amygdala, the identification score was negatively correlated with RD values (r = − 0.435, p = 0.01).

Duration of OD

In the PC-OlfDys group, the duration of OD showed a positive correlation with MD values in the left amygdala (r = 0.504, p = 0.004) and the left posterior piriform cortex (r = 0.385, p = 0.03). A positive correlation was also observed between duration of OD and AD values in the left amygdala (r = 0.532, p = 0.002).

PHQ-8

A negative correlation of PHQ-8 with FA values in the left amygdala (r = − 0.414, p = 0.02) was seen in the PC-OlfDys group. There was also a negative correlation between PHQ-8 and AD values in the left putamen (r = − 0.381, p = 0.03). No correlation was seen in the PC-N group.

GAD-7

A negative correlation with FA values in left amygdala was seen in the PC-OlfDys group (r = − 0.377, p = 0.03). No correlation was seen in the PC-N group.

Discussion

Persistent OD may induce significant alterations in olfactory-related brain regions. Although whole-brain TBSS did not reveal significant between-group differences after FWE correction, the ROI-based approach proved more sensitive in detecting alterations within regions strongly implicated in olfactory processing. This suggests that targeted, hypothesis-driven analyses may provide greater power to uncover subtle yet biologically meaningful effects. Increased FA and RD values within the amygdala region in post-COVID patients with OD, compared to normosmic controls. This may indicate changes of myelination or changes in axonal diameter in the white matter pathways adjacent to the amygdala. Duration of loss was positively correlated with MD and AD values in the left amygdala and posterior piriform cortex. This result suggests that the longer the OD lasts, the more likely it is that these structures will be affected. In addition, people in the PC-OlfDys group had higher scores on the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 questionnaires. It remains to be investigated whether these symptoms are a “behavioural” consequence of persistent OD or whether the symptoms are a consequence of structural changes caused by (post-)COVID (and could be triggered, for example, by an olfactory deficit).

Increased FA in the left amygdala indicates increased myelination, which in turn depicts white matter strength or integrity31. This increased myelination can be interpreted as better communication between the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which, for example, predicts more favourable outcomes in terms of anxiety32. This is supported by the present analyses, which show negative correlations between PHQ-8 and GAD-7 scores and FA values in the left amygdala. This essentially means that as FA levels increase, indicating better myelination, anxiety and depression decrease, mediated by information flow between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. However, FA provides an overall measure of white matter integrity, which may not essentially be true. Microscopic diffusion values, like RD could better explain local structural changes. Increased RD values are generally interpreted as a sign of myelin sheath disruption and neurodegeneration, however, in our study, based on strict inclusion criteria, this does not hold true, in terms of neurodegeneration.

Increased RD values in the right amygdala in the PC-OlfDys group could indicate changes in myelin structure. Discrimination scores were negatively correlated with RD values in the left amygdala. Potential disruptions in myelin sheath integrity may lead to reduced information flow between key brain regions, mainly amygdala and prefrontal cortex. This could lead to reduced discrimination scores, as discrimination is cognitively demanding33,34. The increased RD values in the right amygdala may indicate disruptions in white matter integrity, potentially related to demyelination or axonal damage in pathways associated with olfactory processing. Conversely, the increased FA values in the left amygdala could reflect improved white matter integrity or organization, possibly indicating compensatory mechanisms or adaptations to olfactory deficits.

The association between the duration of olfactory loss and the observed increases in MD and AD values within the left amygdala, as well as with increased MD values in the left posterior piriform cortex, is a point of considerable interest. These regions, recognized as primary olfactory cortex areas, are pivotal in olfactory processing, and any adverse changes within them could indicate persistent OD35. MD and AD values, serving as microscopic indicators of local white matter organization, offer valuable insights into the structural integrity of these brain regions. In the context of PC-OlfDys participants, where prolonged olfactory loss was prevalent, this finding is not only corroborated by existing research, including our own36, but also highlights the potential significance of these structural alterations. It is captivating to speculate that such changes may serve as fundamental drivers behind the persistent symptoms of PC-OlfDys and may potentially manifest as permanent changes.

The PHQ-8 and GAD-7 questionnaires, commonly used as diagnostic tools to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms, showed divergency in these mental health domains in PC-OlfDys. Although not direct measures of depression and anxiety, it is noteworthy that a negative correlation emerged between these markers and diffusion values in the left amygdala and putamen. Previous research has highlighted reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and putamen in individuals with major depressive disorder with anxiety component, a prevalent subtype of major depressive disorder37. Similarly, changes in the amygdala and putamen were observed in the PC-OlfDys group, with a negative correlation detected between olfactory threshold scores and putamen RD, and between olfactory discrimination and identification scores and amygdala RD. Given that olfactory function, depression, and anxiety are interrelated, with cognitive processes playing an important role, structural changes in the white matter areas surrounding the amygdala are likely to have a considerable influence on both olfactory function and mental health outcomes. This suggests a bidirectional relationship between olfactory function and depression and anxiety, with the absence of feedback, as indicated by a decrease in structural connectivity, potentially perpetuating a vicious cycle. Our results are in line with considerable work in the past suggesting a causal relationship between olfaction, anxiety, and depression38,39.

To gain a deeper understanding of the structural consequences of depression, anxiety and OD, a longitudinal study is needed. This will allow to track the progression of the disease and its possible link to depression and anxiety. At this point, a comparison with a post-COVID cohort with depression without OD would also be interesting to see which changes are due to the olfactory deficit and which are due to depression. One of the main limitations of diffusion-based or even functional studies is sample size. Although there is no ideal sample size per se, a sample size of more than 20 participants per group has considerable statistical power for functional or diffusion-based studies40.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights significant brain changes associated with persistent olfactory dysfunction (OD) following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using DTI, we identified alterations in key olfactory-related brain regions, particularly in the amygdala, putamen and piriform cortex, where increased fractional anisotropy and radial diffusivity values suggest both enhanced myelination and potential disruptions in white matter integrity. Our findings also suggest that the longer the OD persists after the infection, the greater the DTI changes within critical olfactory circuits. This may have implications for both olfactory function and mental health outcomes. The observed correlations between diffusion metrics, olfactory scores, and depression/anxiety assessments (PHQ-8 and GAD-7) underscore the complex relationship between prolonged OD and its psychological impact.

Our results add to the growing body of evidence that links post COVID-19 condition with cerebral changes, particularly in olfactory processing regions, and suggests that these alterations may be drivers of persistent symptoms. Future longitudinal studies with larger cohorts and potentially further subcohorts are necessary to further elucidate the trajectory of recovery and the potential for structural and functional brain changes to serve as biomarkers for persistent OD and associated mental health conditions.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from NAPKON but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with permission of NAPKON.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Axial diffusivity

- BET:

-

Brain extraction toolbox

- DTI:

-

Diffusion tensor imaging

- FA:

-

Fractional anisotropy

- FDT:

-

FSL diffusion toolkit

- FSL:

-

FMRIB software library

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7

- MD:

-

Mean diffusivity

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment test

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NAPKON:

-

National Pandemic Cohort Network

- OD:

-

Olfactory dysfunction

- PC-N:

-

Post-COVID normosmic

- PC-OlfDys:

-

Post-COVID olfactory dysfunction

- PHQ-8:

-

Eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire-depression

- RD:

-

Radial diffusivity

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- TBSS:

-

Tract-based spatial statistics

- TDI:

-

Threshold-Discrimination-Identification score

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ellul, M. A. et al. Sep., Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 19(9), 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0 (2020).

Park, J. W., Wang, X. & Xu, R. H. Revealing the mystery of persistent smell loss in long COVID patients. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18 (12), 4795–4808. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.73485 (2022).

Alkanat, H. Ö. & Arslan, S. Long-term smell loss experiences after COVID-19: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 27(2), e14018. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.14018 (2024).

Organization, W. H. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021, Art. no. WHO/2019-nCoV/Post_COVID-19_condition/Clinical_case_definition/2021.1, 2021. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/345824 (accessed 19 Sep 2024).

COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567261/ (accessed 19 Sep 2024).

Stanley, H. B. et al. Identification of the needs of individuals affected by COVID-19. Commun. Med. 4 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00510-1 (2024).

Thomasson, M. et al. Jun., Markers of limbic system damage following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain Commun. 5(4), fcad177. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcad177 (2023).

Voruz, P. et al. Dec., Brain functional connectivity alterations associated with neuropsychological performance 6–9 months following SARS-CoV-2 infection, Human Brain Mapp. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.26163 (2022).

Hosp, J. A. et al. Cerebral microstructural alterations in Post-COVID-condition are related to cognitive impairment, olfactory dysfunction and fatigue. Nat. Commun. 15, 4256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48651-0 (2024).

Yildirim, D. et al. DTI and fMRI study of COVID-19 related anosmia and post viral olfactory dysfunction. Acad. Radiol. 29 (1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2021.10.019 (2022).

Thaploo, D. et al. Functional connectivity patterns in parosmia. Behav. Brain Funct. 19 (1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12993-023-00225-8 (2023).

Mueller, B. A., Lim, K. O., Hemmy, L. & Camchong, J. Diffusion MRI and its role in neuropsychology. Neuropsychol. Rev. 25 (3), 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-015-9291-z (2015).

Muccioli, L. et al. Cognitive and functional connectivity impairment in post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Neuroimage Clin. 38, 103410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103410 (2023).

Mishra, S. S. et al. Tracts in the limbic system show microstructural alterations post COVID-19 recovery. Brain Commun. 6 (3), fcae139. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcae139 (2024).

Campabadal, A. et al. Structural brain changes in post-acute COVID‐19 patients with persistent olfactory dysfunction. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 10(2), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51710 (2022).

Horn, A. et al. Long-term health sequelae and quality of life at least 6 months after infection with SARS-CoV-2: design and rationale of the COVIDOM-study as part of the NAPKON population-based cohort platform (POP). Infection. 49(6), 1277–1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01707-5 (2021).

Hummel, T., Sekinger, B., Wolf, S. R., Pauli, E. & Kobal, G. ‘Sniffin’ sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem. Senses 22(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/22.1.39 (1997).

Croy, I. et al. Comparison between odor thresholds for phenyl ethyl alcohol and butanol. Chem. Senses 34(6), 523–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjp029 (2009).

Oleszkiewicz, A., Schriever, V. A., Croy, I., Hähner, A. & Hummel, T. Updated Sniffin’ Sticks normative data based on an extended sample of 9139 subjects. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 276(3), 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5248-1 (2019).

Kroenke, K. et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 114(1–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026 (2009).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166 (10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal cognitive Assessment, moca: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53 (4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x (2005).

Smith, S. M. et al. Jul., Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 31(4), 1487–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 (2006).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 Suppl 1, S208–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 (2004).

Smith, S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction, Hum. Brain Mapp. 17(3), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.10062 (2002).

Thaploo, D., Georgiopoulos, C., Haehner, A. & Hummel, T. Subtle differences in brain architecture in patients with congenital anosmia. Brain Topogr. 35 (3), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-022-00895-z (2022).

Strauch, C., Hoang, T. H., Angenstein, F. & Manahan-Vaughan, D. Olfactory information storage engages subcortical and cortical brain regions that support valence determination. Cereb Cortex 32(4), 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab226 (2022).

Georgiopoulos, C. et al. A study of neural activity and functional connectivity within the olfactory brain network in parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 23, 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101946 (2019).

Heller, C. et al. Modulating salience network connectivity through olfactory nerve stimulation. Transl. Psychiatry. 15 (1), 303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03500-6 (2025).

Chao, Y. T., Liao, Y. C., Hsu, P. S. & Thaploo, D. Altered white matter architecture in patients with isolated congenital anosmia. Brain Struct. Funct. 230 (5), 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-025-02942-4 (2025).

Beaulieu, C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system—a technical review. NMR Biomed. 15, 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.782 (2002).

Kim, M. J. & Whalen, P. J. The structural integrity of an Amygdala–Prefrontal pathway predicts trait anxiety. J. Neurosci. 29 (37), 11614–11618. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2335-09.2009 (2009).

Audronyte, E., Pakulaite-Kazliene, G., Sutnikiene, V. & Kaubrys, G. Odor discrimination as a marker of early Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 94(3), 1169. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-230077 (2023).

Hedner, M., Larsson, M., Arnold, N., Zucco, G. M. & Hummel, T. Cognitive factors in odor detection, odor discrimination, and odor identification tasks, J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 32(10), 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803391003683070 (2010).

Patin, A. & Pause, B. M. Human amygdala activations during nasal chemoreception. Neuropsychologia. 78, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.009 (2015).

Hummel, T. et al. Advancement of PD is reflected by white matter changes in olfactory areas: A pilot study. Med. (Kaunas). 57 (11), 1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111183 (2021).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Common and specific alterations of amygdala subregions in major depressive disorder with and without anxiety: A combined structural and Resting-State functional MRI study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 634113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.634113 (2021).

Herrmann, T., Koeppel, C., Linn, J., Croy, I. & Hummel, T. Olfactory brain activations in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 10072. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36783-0 (2023).

Croy, I., Nordin, S. & Hummel, T. Olfactory disorders and quality of life–an updated review. Chem. Senses 39(3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjt072 (2014).

Hanspach, J. et al. Sample size estimation: current practice and considerations for original investigations in MRI technical development studies. Magn. Reson. Med. 85 (4), 2109–2116. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28550 (2021).

Acknowledgements

It was a great pleasure to collaborate with Thomas Hummel, Smell & Taste Clinic, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, TU Dresden, Germany, to whom we are most grateful for useful discussions and constant support! We gratefully thank all NAPKON sites that contributed patient data and/or biosamples for this analysis. The representatives of the NAPKON sites who contributed at least 5 per mille to this analysis are (in alphabetical order): University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein Kiel, Kiel (Franzpoetter K, Hermes A, Lehmann I, Meier S, Pape D, Poick S, Reinke L, Tamminga T). We gratefully thank all participating NAPKON and NUKLEUS infrastructures that contributed to this analysis. The representatives of these NAPKON and NUKLEUS infrastructures are (in alphabetical order): Charite - Universitaetsmedizin Berlin, Berlin (Fricke J, Krist L, Lorbeer R, Schaller J), Helmholtz Center Munich, Munich (Kraus M, Lorenz-Depiereux B), University Hospital Cologne, Cologne (Brechtel M, Fiedler K, Hopff SM, Laugwitz M, Lee C, Nunes de Miranda S, Schulze N, Seibel K, Wagner P), University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt (Appel K, Geisler R, Hagen M, Schneider J, Weirauch T, Weismantel C, Wolf L), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel (Hermes A, Tamminga T), University Hospital Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg (Guenther K, Haug F, Haug J, Horn A, Kohls M), University Hospital Wuerzburg and University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg (Fiessler C, Heuschmann PU, Miljukov O, Nuernberger C, Reese JP, Schmidbauer L), University Medicine Goettingen, Goettingen (Chaplinskaya I, Hanss S, Krefting D, Pape C, Rainers M, Schoneberg A), University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald (Bahls T, Hoffmann W, Nauck M, Schaefer C, Schattschneider M, Stahl D, Valentin H), University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg (Jiru-Hillmann S). We gratefully thank the NAPKON Steering Committee: University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Giessen (Herold S), University of Würzburg, Würzburg (Heuschmann P), Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin (Heyder R), University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald (Hoffmann W), Hannover Unified Biobank, Hannover Medical School, Hannover (Illig T), University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel (Schreiber S), University Hospital Cologne and University Hospital Frankfurt, Cologne and Frankfurt (Vehreschild JJ), Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin (Witzenrath M).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. NAPKON is part of the NUM, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (FKZ: 01KX2121).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T., L.S., N.B., S.G., S.A., M.L., Contributed equally to the manuscript data analysis, writing, editing, reviewing. M.L., Conceptualization, review, writing and editing C.F., A.R., W.L., S.S., W.M., C.M., M.K., N.W., T.B., S.S., K.F., J.J.V., O.J., C.M. Editing and reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thaploo, D., Schmill, LP., Behrend, N. et al. Alterations of the amygdala in post-COVID olfactory dysfunction. Sci Rep 15, 36104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23015-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23015-w