Abstract

Chromium (Cr) critically enhances interfacial compatibility and mechanical properties of titanium (Ti) -based coatings, however, the specific effects of Cr content on microstructural evolution remain underexplored. In this study, Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (x = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings were fabricated on Ti-6Al-4V (TC4) titanium alloy via laser cladding. The phase composition of the coating/annealed TC4 was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The microstructure was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the grain orientation was analyzed by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) attached to the SEM. The effects of Cr content on the microstructural evolution and grain characteristics of the coatings were investigated, and the resultant variations in mechanical properties were further analyzed. Results indicate that increasing Cr content promotes Ti4Cr/Cr2AlC precipitation, reduces Ti8C5 and increases Ti5Si3. Notably, the orientation strength of Ti5Si3 is enhanced, and the grain size of the coating is refined. Both the TC4 substrate and the laser-cladding coatings exhibit strain rate strengthening behavior. Crucially, yield strength, peak stress, and microhardness positively correlate with Cr content. At identical indentation depth, maximum load, indentation hardness, and Young’s modulus progressively increase with Cr content, exceeding TC4 substrate values. Although friction coefficients rise with Cr content, the coating with 5 wt% Cr (Cr5) demonstrates minimal wear weight loss. This study highlights the potential of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx coatings for aerospace applications, offering a unique combination of refined microstructure and superior mechanical performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Titanium and its alloys, renowned for their exceptional specific strength, superior impact toughness, and excellent corrosion resistance, serve as the primary structural materials for cold-end components, particularly compressor blades, in aero-engines1,2,3. Despite these advantages, titanium and its alloys are hindered by several limitations, including low surface hardness, low work-hardening rate, and inadequate wear resistance4,5,6. To ensure the operational safety of these components and mitigate the risk of failure, titanium-based coatings are frequently employed in engineering applications to enhance the overall mechanical properties of titanium alloy surfaces7,8. Given the pronounced sensitivity of TC4 titanium alloy to heat input, laser cladding emerges as an optimal surface enhancement strategy. This technique affords a higher energy density and cooling rate compared to electric arc or plasma cladding, leading to a finer microstructure, a narrower heat-affected zone, and minimal substrate deformation. Moreover, whereas electron beam cladding necessitates a vacuum chamber, laser cladding operates in a non-vacuum environment, granting superior flexibility for the in-situ treatment of complex geometries9,10,11.

To mitigate the impact of heterogeneous interfaces, laser cladding was employed to fabricate Ti-Al based coatings on TC4 titanium alloy substrates, with the objective of enhancing surface hardness and wear resistance12. The influence of ceramic powder content on the microstructure, hardness, and wear resistance of the coatings was systematically investigated by varying the ceramic powder concentration within the Ti-Al mixed powder system. For instance, the addition of SiC facilitated the precipitation of reinforcing phases, namely Ti5Si3 and TiC, within the coatings, thereby enhancing material hardness and reducing the friction coefficient13,14. Within the range of 0–6%, the progressive increase in TiC content promoted the formation of Ti3AlC2, where TiC served as a reinforcing phase, consequently improving the coating’s hardness and wear resistance15.

Chromium (Cr) is a widely utilized alloying element in wear-resistant steels due to its significant role in carbide formation and modification. Extensive research has demonstrated that Cr not only promotes carbide formation but also alters the microstructure, morphology, and properties of these carbides, thereby enhancing the wear resistance of coatings. To systematically evaluate the influence of Cr content on coating performance, Fe-Crx-B coatings were fabricated using laser cladding technology, and experimental results revealed a positive correlation between Cr content and coating hardness, with the optimal performance achieved at 12 wt% Cr content16. The enhancement of wear resistance through Cr addition has been well-documented in the literature. Particularly, Cr-containing intermetallic compound coatings have demonstrated exceptional properties, including high hardness, refined microstructure, and robust intermetallic atomic bonding, which collectively contribute to their excellent wear resistance under dry sliding wear test conditions17,18.

To further elucidate the influence of Cr on the comprehensive performance of laser additive manufactured components, the strategic design of V/Cr transition layers effectively suppresses the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds at the interface between titanium alloy substrates (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V) and nickel-based coatings, elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of transition layers on interfacial microstructure evolution and mechanical performance enhancement19. In Ni-Cr-Ti-B4C composite coatings fabricated on Ti-Al intermetallic and Q235 steel substrates, laser-specific energy (Es) demonstrates precise control over ceramic phase distribution, resulting in a 40–60% improvement in coating hardness and significantly enhanced wear resistance20. Cr exhibits dual-phase modulation capabilities: In Ti-xCr graded systems, β-solution heat treatment induces multi-phase transformations (e.g., α→β→α’ martensite), enabling tailored adjustment of Young’s modulus21, while in Ni-Ti-xCr coatings, increased Cr content drives a transition from columnar to equiaxed grain structures and promotes the formation of continuous Cr-rich intermetallic strengthening phases (e.g., Cr2Ti and Cr3Ni2)22. For nickel-based superalloys, optimized Cr/Mo ratios combined with solution-aging treatments regulate γ-dendritic morphology and facilitate homogeneous precipitation of γ”-strengthening phases (volume fraction > 35%), offering innovative strategies for high-temperature component optimization23. These findings establish a theoretical foundation for laser additive manufacturing of high-performance metal matrix composites, emphasizing the critical synergy among compositional design, process parameters, and post-processing strategies in achieving tailorable material properties.

In summary, Cr plays a pivotal role in enhancing the mechanical properties of titanium-based coatings. To clarify the influence of Cr on the mechanical properties and wear resistance of coatings, and to reveal the strengthening and toughening mechanism of coatings, laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings were taken as objects to comprehensively examines the influence of Cr content on microstructural evolution, microhardness, dynamic mechanical properties, and wear resistance characteristics. These findings provide substantial experimental data and theoretical insights for optimizing surface hardness, strength, and wear resistance in titanium alloy applications.

Materials and methods

Materials preparation

Ti, Al, SiC and Cr powders (Chengdu Huayin Powder Technology Co., Ltd.) were selected as the raw materials for laser cladding of titanium-based coatings, and the microscopic morphology of the powders was shown in Fig. 1a–d. Ti and Al powders exhibited a spherical morphology, with high fluidity, while SiC and Cr powders exhibited an irregular block shape, with poor flowability. In order to minimize the effect of powder fluidity on the laser cladding process, the pre-powder method was used for cladding. A particle size analyzer (Hydro 2000SM, Malvern Panalytical) was employed to measure the particle sizes of the powders. The particle size distributions for Ti, SiC, and Cr powders were presented in Fig. 1e–g, respectively. The Ti powder demonstrated D10, D50, and D90 values of 19.26 μm, 36.22 μm, and 63.05 μm, respectively. The SiC powder exhibited corresponding values of 70.65 μm, 101.06 μm, and 137.78 μm, respectively, and D10, D50, and D90 values of the Cr powder were 20.03 μm, 38.37 μm, and 65.65 μm, respectively. All powder particle sizes conform to a lognormal distribution. Additionally, the Al powder exhibits a particle size range of 50 to 100 μm and possesses a purity level of 99.9%. Since Al is a highly reactive metal and may react with ions dissolved in water to produce hydrogen. Due to experimental constraints, its particle size distribution was not tested.

TC4 titanium alloy (with dimensions of 60 mm × 60 mm × 20 mm) was used as the cladding substrate. The laser cladding powders were prepared using Ti, Al, SiC, and Cr as raw materials according to the compositions listed in Table 1. As shown in the table, the relative proportions of Ti, Al, and SiC were maintained constant, while the Cr content in the powder mixture was varied at 0 wt%, 5 wt%, 10 wt%, and 15 wt%. These compositions were designated as Cr0, Cr5, Cr10, and Cr15, respectively. This approach ensured that any effects observed could be attributed solely to the variation in Cr content, thereby eliminating potential uncertainties arising from changes in the proportions among Ti, Al, and SiC. The metal powder was homogenized using a mixer (JHX100L, Zhengzhou Jinhe Equipment Manufacturing Co., Ltd.) before cladding, and the mixing parameters were set at a speed of 20 r/min for a duration of 1 h. After the powder was thoroughly mixed, it was placed in an atmospheric furnace (HMX 1600-30, manufactured by Shanghai Haoyue Electric Furnace Technology Co., Ltd.) and dried at 100 °C for 2 h.

The substrate surface was sequentially polished with sandpaper of 300, 600, 1200, and 2000 grit sizes and subsequently cleansed with anhydrous ethanol to remove impurities. Fiber laser cladding equipment (RFL-C6000, Wuhan Raycus Fiber Laser Technology Co., Ltd.) was used for laser cladding, S-type reciprocating scan pattern and preset powder feeding method were adopted. (Fig. 2a,b). Four different powder ratios were utilized to prepare four coatings with a thickness of 1 mm and another set of four coatings with a thickness of 5 mm (multiple powder claddings). 1-mm-thick coatings were produced by single-layer cladding, while 5-mm-thick coatings were fabricated in three layers with an inter-track overlap ratio of 50%. The laser power, scanning speed, and spot diameter during cladding were set to 1800 W, 10 mm/s, and 3 mm, respectively. In order to inhibit oxidation of the material, 99% pure argon gas was used as a protective gas. To facilitate subsequent microstructure characterization and mechanical property evaluations, the coatings were precisely cut by wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM) according to the size of the test specimens, as illustrated in Fig. 2c, d. The square-shaped specimens were used for XRD, SEM, EBSD, nanoindentation, friction and wear tests, and the cylindrical specimens were used for dynamic mechanical property tests.

Characterization and testing methods

The coating materials with four powder ratios were characterized by XRD, SEM and EBSD to analyze the influence of Cr content on the microstructure and crystal characteristics of the materials. Then the mechanical property tests were conducted on four types of coating materials to investigate the effect of microstructure changes on the mechanical properties of the coatings. The specific characterization and testing methods are as follows:

The coatings were polished with argon ions. After polishing, the specimen surfaces were etched with a solution of HF: HNO3: H2O in a ratio of 3:6:91 (Volume ratio). An X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker) was used for the physical phase analysis of the coating, and the test was performed in continuous scanning mode with a voltage of 40 KV, a current of 15 mA, a diffraction angle of 10–90°, a scanning speed of 8°/min, and a step size of 0.2°. The surface micromorphology of the coatings was observed using a scanning electron microscope (Sigma 300, ZEISS), and the elemental distribution of the coatings was analyzed using its equipped energy disperse spectrometer (EDS). The crystal structure of the coating was characterized by the electron backscatter diffraction method and EBSD probe (C-Nano EBSD, Oxford).

The mechanical properties of the coatings were tested by Vickers hardness tester (402 MVD, Vickers), nanoindentation tester (U9820A Nano Indenter G200, Agilent), split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) device (Leway Technology Φ14.5, Luoyang Leway Technology Co., Ltd.), and friction testing machine (UMT 2MT, USA-CETR). The surface morphology of the wear scars on the coatings was observed by three-dimensional profile tester (VR 3200, Keyence). Vickers hardness test parameters included a load of 200 g and a duration of 10 s. Nanoindentation test parameters included static displacement mode, a maximum indentation depth of 1 μm, and a maximum load duration of 10 s. Dynamic compression mechanical properties test parameters included loading strain rates of 120 s−1, 180 s−1, and 300 s−1. Friction and wear test parameters included a ball-block type friction pair, a Si3N4 ball with a diameter of 6 mm as the friction counterpart.

Results and discussion

Phase identification

Figure 3 illustrates the XRD patterns of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. As shown in the figure, the cladding coating phases mainly include ceramic phase compounds such as Ti5Si3, TiC, Ti8C5 and Cr2AlC, as well as intermetallic compounds such as Ti3Al and Ti4Cr. Ti5Si3, Ti3Al, TiC and Ti8C5 characteristic peaks are present in the Cr0 coating, and intermetallic compounds Al2Cr, Ti4Cr and ceramic compound Cr2AlC characteristic peaks are newly appeared in the Cr5 coating. Compared to the Cr5 coating, the characteristic peaks of the intermetallic compound Al2Cr disappear in the Cr10 coating, and the characteristic peaks of the intermetallic compounds Ti4Cr and Al2Cr disappear in the Cr15 coating. The characteristic peaks of SiC were not seen in any of the Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings, which may be due to the in-situ formation of C and Ti that are dissociated from SiC. In addition, due to the lowest Gibbs free energy of the Ti5Si3 hard phase during laser cladding24, the Ti element reacts preferentially with the Si element to form ceramic phase compounds. The chemical reaction formulas involving Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) cladding coatings during the melt pool reaction are as follows:

Microstructural characterization

Metallographic analysis

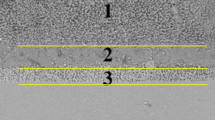

Figure 4 illustrates the macroscopic cross-sectional morphology of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. As shown in Fig. 4a–d, the thicknesses of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings are 1188 μm, 1186 μm, 1175 μm, and 1158 μm, respectively, the cross-section of cladding coating do not show obvious defects. However, the high energy in the laser cladding process leads to sublimation of a small portion of Ti, Al and SiC powders, and the sublimated gases fail to completely evaporate from the molten metal, so that pores would be formed inside the coatings as the molten metal solidified. Additionally, with a laser power of 1800 W, the peak temperature of the melt pool can reach 2000–2500 ℃. Under this high-energy input, partial decomposition of SiC occurs, accompanied by localized ablation that generates pores in the coating structure. By observing the interfacial position between the coating and the TC4 substrate, a good metallurgical bond exists between the two.

Figure 5a-h illustrates the surface micromorphology of laser cladding coated Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. Table 2 shows the EDS analysis results corresponding to the labelled regions in Fig. 5e-h. Taking Fig. 5e as an example, points A1, B1, and C1 mark EDS analysis locations. All points are situated at the center of single-phase regions (away from grain or phase boundaries) to ensure that the EDS data reflect solely the composition of the target phase. A1 corresponds to the dendritic/blocky hard phase, B1 to the continuous matrix phase (i.e., the network-like phase), and C1 to the ellipsoidal phase. The phase types were determined by combining the microchemical composition obtained via EDS point analysis with phase identification results from XRD. For instance, at point C3 in the dendritic-blocky region of Cr10 coating, the Ti/Cr atomic ratio was 4.86:1. Cross-referencing with Ti₄Cr peaks in Fig. 3 confirmed this phase as Ti₄Cr intermetallic. On this basis, combining Fig. 5a–d; Table 2, it can be seen that the microstructure of the coatings mainly consists of ellipsoidal and long block phases, and Cr5 and Cr10 show similar microstructures including ellipsoidal dendritic phase (Ti8C5), long block phase (Ti5Si3), and matrix phase (Ti3Al)25. From Fig. 5a, it can be seen that the size of ellipsoidal Ti8C5 is about 2–4 μm with a relatively uniform distribution, while the Ti3Al matrix phase exhibits a reticular structure. Ellipsoidal Ti8C5 with a size of about 3–5 μm is observed in Fig. 5b, and the size of the ellipsoidal particles is obviously increased compared to that in Fig. 5a. More long block phases Ti5Si3 are also observed in the coating, and Ti4Cr appears in the Ti3Al matrix. Compared with Fig. 5b, the size of long block Ti5Si3 in Fig. 5c increases, the proportion of ellipsoidal Ti8C5 decreases, and Ti8C5 aggregates around the Ti5Si3 structure to form a dendritic structure. In Fig. 5d, the ellipsoidal Ti8C5 is unevenly distributed, the size of Ti5Si3 in the long block phase decreases, and a continuous layered Cr2AlC phase is also observed. TiC agglomerates with a size of about 15 μm are observed in all four coatings.

EBSD analysis

Figure 6 illustrates the crystal orientation and both pole figures and inverse pole figures of Ti-Al-SiC-Cr5 and Ti-Al-SiC-Cr15 coatings. The phase identification shows that the Cr5 coating consists of 47.3% Ti8C5 and 37% Ti5Si3, the Cr15 coating contains 27.3% Ti8C5 and 52.7% Ti5Si3, and the content of Ti8C5 and Ti5Si3 varies greatly between the two coatings. Figure 6a, b illustrate the Ti8C5, Ti5Si3 and Cr2AlC orientations in Cr5 and Cr15, with colours distinguishing grain orientations. Comparing the two figures, it is found that the intergrain boundaries of the Cr5 and Cr15 coatings are clearly defined. The Cr content significantly influences the crystal orientation within these coatings, and the Cr5 coating exhibits a widely dispersed crystal orientation across the observation area. In contrast, the Cr15 coating demonstrates a more uniform orientation among adjacent grains, with obvious texture characteristics.

Figure 6c, d illustrate the pole figure and inverse pole figure of Ti8C5 in Cr5 and Cr15 coatings, similarly, Fig. 6e, f show the pole figure and inverse pole figure of Ti5Si3 in Cr5 and Cr15 coatings. Table 3 shows the values of the crystal orientation and pole density values of Ti8C5 and Ti5Si3 in Cr5 and Cr15 coatings. The phase identification process for Ti₈C₅ is exemplified as follows. Initially, non-stoichiometric titanium carbide Ti₈C₅ (tetragonal crystal system, space group P4/mbm) was preliminarily identified in the coating via XRD (Fig. 3) as a candidate phase. Subsequently, based on SEM morphological observations (Fig. 5), typical blocky structural regions were identified to avoid interference from phase boundaries, and EBSD analysis was conducted within these selected areas. The phase was identified as Ti8C through geometric matching of the acquired Kikuchi diffraction patterns with crystallographic databases. A positive identification was confirmed when the confidence index (CI) exceeded 0.2 and the geometric characteristics were distinctly different from those of similar phases such as cubic TiC. As shown in Fig. 6; Table 3, compared to the Cr5 coatings, the values of the orientation strength of Ti8C5 in the Cr15 coating slightly decreases, but the value of the orientation strength of Ti5Si3 is significantly increases, indicating that the strength of crystal orientation increases with the increase of Cr content. Attributed to the orderliness and orientation of the grain arrangement, the material is able to exhibit higher strength and hardness when the strength of the preferential orientation is high.

Figure 7a illustrates the statistics of low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs) and high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs) of Cr5 and Cr15 coatings. As shown in the figure, the proportion of HAGBs and LAGBs in Cr5 coating is 92.37% and 7.63%, respectively, and the Cr15 coating exhibits a marked rise in the proportion of LAGBs to 16.59%. This observation indicates that as the Cr content increases, there is a corresponding increase in the proportion of LAGBs.

Figure 7b shows the grain size statistics of Cr5 and Cr15 coatings. The statistical results indicate that the average grain size decreased from 3.3 μm for the Cr5 coating to 1.4 μm for the Cr15 coating. Compared with the Cr5 coating, the percentage of grains with grain size less than 2 μm increased from 50.96% to 65.13% for the Cr15 coating, the percentage of grains with size 2–3 μm remains relatively unchanged, and the percentage of grains with size 3–10 μm decreased. The gradual refinement of the coating grains with increasing Cr content may be due to the fact that a large amount of Cr in the Cr15 coating can increase the number of nucleation sites and improve the nucleation rate. In addition, the carbides formed by Cr and C provides more heterogeneous nucleation sites for the generation of other phases. In general, the refined grains can lead to a further increase in material strength and hardness26.

Laser cladding pool model

The evolution of material phases in the molten pool during the laser cladding process was mapped through the combination of material phase identification, surface morphology analysis and crystal structure characterization, as shown in Fig. 8. During the laser cladding process, Ti, Al, SiC and Cr powders are transformed into Ti, Al, Si, C and Cr active elements under the high temperature of the high-energy laser beam, as the laser heat input increases, the molten pool is gradually formed, and the elements in the molten pool are recombined under the effect of Marangoni convection induced by the interfacial tension gradient27. Ti preferentially combines with Si to form compounds, with the first precipitated Ti5Si3 serving as heterogeneous nucleation points in the subsequent nucleation process28. The remaining active elements react to generate carbides such as TiC and Ti8C5 and intermetallic compounds like Ti3Al. Due to the relatively simple combination of Ti and C element, the reaction of intermetallic elements will be slightly delayed. As the temperature decreases, the material will further solidify, aggregation phenomenon will occur between some of the phases to form dendritic crystals, while in other regions of the molten pool, ellipsoidal and spherical equiaxial crystals will form later.

Microhardness

Figure 9 illustrates the microhardness of the cross-section of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings and the variation of hardness along the depth direction of the coatings. Figure 9a shows that the average microhardness of Cr0, Cr5, Cr10 and Cr15 coatings are 841.0HV0.2, 903.3HV0.2, 926.0HV0.2 and 989.5HV0.2, which are 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.7 times higher than that of TC4 (370.8HV0.2), respectively. A monotonic increase in average microhardness was observed with increasing Cr content. This is due to the precipitation of hard phases, such as TiC, Ti8C5, Ti5Si3 and Cr2AlC in the process of laser cladding. The gradual increase of hard phases and grain refinement result in a gradual increase in the microhardness of the coatings.

Figure 9b shows the trend of microhardness of the coating along the depth of the laser cladding layer. The microhardness of the cladding layer is significantly higher than that of the substrate and decreases gradually in the heat-affected zone. This is due to the fact that the closer to the bottom of the melt pool, the smaller the thermal influence of laser cladding, the larger the grain size, and the lower the proportion of hard phase, resulting in a decrease in microhardness. In addition, the hardness in the heat-affected zone is still higher than that of the TC4 substrate due to the phase hardening and grain refinement of the material in the heat-affected zone. Data analysis confirms that variations in average values are consistent with theoretical predictions of Cr-induced microstructural changes. Given the monotonic increase in hardness and inter-group differences significantly exceeding typical instrument measurement errors, these variations are statistically significant and practically significant.

Indentation hardness and Young’s modulus

Figure 10a illustrates the load-displacement curves for nanoindentation experiment of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. During indentation testing, owing to the difficulty in isolating individual phases, a grid indentation array (spacing: 2 mm) was employed to determine the indentation locations. Seven indentations were performed on each coating and the results were averaged to obtain the overall mechanical properties of the region. The curves show that the load-displacement curves are continuous and smooth from the time the indenter is pressed into the coating to the end of the indentation experiments. Notably, no significant step features are observed within these curves, which indicates that the coatings are free from cracking and crushing during the loading process29.

The maximum load, indentation hardness and Young’s modulus of the four coatings are given in Fig. 10b. At an indentation depth of 1000 nm, the maximum load required for the four coatings increased by 47, 61, 86 and 129 mN and the indentation hardness increased by 2.387, 3.758, 6.319 and 7.599 GPa, respectively, relative to TC4 (88 mN, 4.174 GPa). It can be seen that with the increase of Cr content, Cr2AlC hard phase was precipitated in the coating, and the proportion of Ti5Si3 hard phase increased, which led to a gradual increase in the indentation hardness of the coating.

The Young’s modulus of the four coatings are 167.445, 164.377, 194.231, and 231.972 GPa, respectively, which are also substantially improved compared with that of TC4 (135.101 GPa). The difference in Young’s modulus between Cr0 and Cr5 coatings is only 3.068 GPa, indicating that the intermetallic compounds Al2Cr and Ti4Cr exert minimal influence on the Young’s modulus.

Dynamic compressive mechanical properties

To investigate the effect of Cr content on the dynamic compression mechanical properties of composite coatings, dynamic compression experiments were performed on TC4 titanium alloy and Ti-Al-SiC-Crx composite coatings using a split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) device with a bar diameter of 14.5 mm at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. The experimental setup and testing principle refer to reference30. The bar system utilized steel bars fabricated from 55CrSi spring steel, with an elastic modulus (E) of 210 GPa, a density of 7.85 g/cm³, and an approximate stress wave velocity of 5100 m/s. The striker bar measured 300 mm in length, while both the incident and transmission bars were 1000 mm long. The absorber bar length was 600 mm. During testing, the signal gain for both the incident and transmission bars in the ultra-high dynamic strain acquisition system was set to 500.

Cylindrical specimens are conventionally employed in Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) experiments. To ensure the validity of axial true strain measurements even under significant plastic deformation, the specimen diameter is typically maintained within 80% of the bar diameter (Ø 14.5 mm). Accordingly, specimens with a diameter of 5 mm and a thickness (length) of 4 mm were designed based on the existing bar diameter. To ensure data reliability, each experiment was repeated in triplicate.

Figure 11 illustrates the stress-strain curve derived from dynamic compression tests on laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. Subfigures (a), (b), (c) and (d) illustrate the stress-strain responses for Cr0, Cr5, Cr10, and Cr15 coatings, respectively. As observed in the figure, the peak stress of the coating increases with the increase of strain rate, demonstrating a distinct strain rate strengthening effect.

The yield strengths of the Cr15 coating at 300 s−1, as well as the peak stresses and peak strains of all four coatings at 120 s−1, 180 s−1, and 300 s−1, have been extracted from Fig. 11 and are presented in Fig. 12. Since no distinct yielding phase is observed in the stress-strain curves, the stress value corresponding to 0.2% plastic strain is taken as the yield strength.

As shown in Fig. 12a, the yield strength of the four coatings increases from 720 MPa for Cr0 to 945 MPa for Cr15 at a strain rate of 300 s−1. The yield strength of the coating exhibits a gradual increase with rising Cr content. As illustrated in Fig. 12b, the peak stresses of the four coatings are similar at each loading strain rate. The peak strains of four coatings at identical peak stresses decrease gradually with increasing Cr content. For example, at a strain rate of 300 s−1, the strains of the four coatings are 0.0313, 0.298, 0.276 and 0.261, respectively, indicating that the strength and plastic deformation resistance of the coatings increase with increasing Cr content under high strain rate loading. The above phenomenon is attributed to the precipitation of the Cr2AlC phase and the increase of the Ti5Si3 phase content as the Cr content increases, which leads to an increase in the hardness of the coating. On the other hand, grain refinement leads to an increase in the total area of grain boundaries and an increase in dislocation barriers. This means that an increase in the number of grains with different orientations needs to be coordinated, thereby giving the coating greater plastic deformation resistance.

Wear resistance

To evaluate the tribological properties of the laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (x = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings, sliding wear tests were conducted at room temperature. The tests were performed under a load of 10 N, a reciprocating frequency of 5 Hz, a wear track diameter of 6 mm, and a duration of 30 min. All tests were repeated three times, and the average values were reported as the final results. The friction curves and schematic diagram of the coatings are presented in Fig. 13a-d. During the initial stage of the friction experiments, the relative friction between the friction pair and the coating is unstable, resulting in some fluctuations in the initial stage of the curves31. The coefficient of friction (COF) curves of different coatings exhibit a typical sawtooth fluctuation patter due to the periodic accumulation and elimination of wear debris on the worn surface32. As illustrated in Fig. 13a, the friction coefficients of the four coatings are 0.43, 0.46, 0.5, and 0.56 respectively, and the results indicate that the friction coefficients of the coatings increase gradually with the increase of Cr content. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that as Cr content increases, the presence of Cr2AlC and Ti5Si3 hard phases within the coating increases, subsequently enhancing the surface hardness of the coating. In contrast, for TC4 and coatings with a lower Cr content, the soft phases within the coating act as lubricants during the friction and wear process, thereby reducing the coefficient of friction. On the other hand, the contact state and contact area of the friction pair also have an effect on the friction coefficient. As the hardness of the coating increases, fragments of the hard phase are prone to adhering to the friction pair, which leads to an increase in the contact area between the friction pair and the coating, thereby resulting in an increase of coating friction coefficient33,34.

Figure 13b compares the wear volume and wear rate of the four coatings. The wear loss of all four coatings is lower than that of TC4 (1.73 mg), with the Cr5 coating exhibiting the lowest wear loss of 1.44 mg. The wear rate of the coating is calculated based on the wear volume using Archard’s wear rate equation W = V/(L×S), where V is the wear volume in mm3, L is the normal force in N, and S is the total sliding distance in m35. The wear rates of the four laser cladding coatings are as follows: 2.25 mm3 N−1m−1 for Ti-Al-SiC-Cr0, 0.75 mm3 N−1m−1 for Ti-Al-SiC-Cr5, 1.75 mm3 N−1m−1 for Ti-Al-SiC-Cr10, and 1.37 mm3 N−1m−1 for Ti-Al-SiC-Cr15. In general, material hardness positively correlates with wear resistance. However, experimental results indicate that the wear amount and rate of Cr10 and Cr15 coatings are greater than those of the Cr5 coating. This anomaly can be attributed to the increased presence of hard phases in the Cr10 and Cr15 coatings. During the wear process, generated wear debris tends to adhere to the coating surface, resulting in friction between the wear debris and the friction pair, which leads to an increase in the wear amount and wear rate.

Figure 13c shows the depth-width curves of the friction scars, as shown in the Ti-Al-SiC-Crx coatings, the widths of the wear scars of the Cr0, Cr5, Cr10, and Cr15 coatings are 1657 μm, 1253 μm, 1558 μm, and 1465 μm. The Cr5 coating presents the smallest depth and width of the wear scars. The Cr10 and Cr15 coatings exhibit similar wear depth and width, while the Cr0 coating exhibits the largest wear depth and width. The results show that the Cr5 coating have better wear resistance while the Cr0 coating have poorer wear resistance. In the Cr5 coating, Ti₃Al (a soft phase) and hard particles (Ti₄Cr, TiC, and Ti₅Si₃) co-form an optimized “soft-hard composite” structure. During the friction process, the soft Ti₃Al phase undergoes selective plastic deformation, forming a continuous, dense lubricating film on the worn surface. Simultaneously, finely dispersed spherical TiC and Ti₅Si₃ particles resist abrasive wear plowing. EBSD analysis revealed a larger average grain size (3.3 μm) and higher proportion of HAGBs (92.37%) in the Cr5 coating. This microstructure deflects and blunts microcracks, inhibits propagation along brittle phases, and suppresses macroscopic brittle delamination.

Figure 14a-d illustrates the 3D morphology of wear scars for laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings. The wear area is denoted by the blue region, and the darker the color, the more severe the wear.

As illustrated in the figure, the wear scars in the Cr10 and Cr15 coatings exhibit a fluctuating groove pattern. This can be attributed to the presence of harder phases such as TiC, Ti8C5, Ti5Si3, and Cr2AlC in the wear debris of these coatings during the wear process. The wear debris predominantly exhibits a granular morphology, accompanied by a small amount of clumps. The hard phases are torn and agglomerated on the coating surface under the action of the Si3N4 ceramic balls, forming granular debris that undergoes abrasive wear with the Si3N4 ceramic balls and the coating surface. However, the wear scars of the Cr5 coating show slight grooves. This is due to the existence of Al2Cr, Ti3Al and Ti4Cr soft phases in the Cr5 coating, which produce flake wear debris for lubrication. Furthermore, The Cr5 coating exhibits a lower hard phase content compared to the Cr10 and Cr15 coatings, resulting in relatively less granular debris.

Conclusion

-

1.

The laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC-Crx (X = 0, 5, 10, 15) coatings primarily consist of TiC, Ti3Al, Ti8C5, and Ti5Si3 phases. As the Cr content increases, the Ti4Cr and Cr2AlC phases gradually precipitate, accompanied by a reduction in the proportion of the ellipsoidal Ti8C5 phase and an increase in the long block-like Ti5Si3 phase within the microstructure. Concurrently, the grain size is refined, and the fraction of low-angle grain boundaries progressively rises.

-

2.

The surface microhardness of the coatings enhances with increasing Cr content, although it diminishes gradually from the heat-affected zone toward the substrate. During nanoindentation experiments, the coatings exhibit no signs of cracking or crushing. Furthermore, the maximum load, indentation hardness, and Young’s modulus of the coatings consistently improve with higher Cr content.

-

3.

Under dynamic compressive loading, the stresses of the cladding coatings increase with increasing strain. Both the yield strength and peak stress of the coatings rise with higher strain rates, demonstrating a pronounced strain rate strengthening effect. At a constant strain rate, the yield strength of the coatings increases, while the peak strain decreases as the Cr content increases.

-

4.

During the friction and wear process, the soft Ti4Cr phase acts as a lubricant, while the hard Ti5Si3 and Cr2AlC phases, which increase in proportion with higher Cr content, contribute to an elevated friction coefficient. Among the coatings, Cr5 exhibits the lowest wear rate. Compared to Cr0, Cr10, and Cr15 coatings, Cr5 demonstrates superior plasticity while maintaining high strength and hardness, showcasing the best overall performance.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.L.

References

Gao, K. et al. Overview of surface modification techniques for titanium alloys in modern material science: A comprehensive analysis. Coatings 14, 148 (2024).

Li, Y., Zhou, Z. & He, Y. Tribocorrosion and surface protection technology of titanium alloys: A review. Materials 17, 65 (2023).

Han, X. et al. Surface modification techniques of titanium and titanium alloys for biomedical orthopaedics applications: A review. Colloids Surf., B. 227, 113339 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Application of ultrasonic nanocrystal surface modification (UNSM) technique for surface strengthening of titanium and titanium alloys: A mini review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 11, 351–377 (2021).

Wang, Z., Tan, Y. & Li, N. Powder metallurgy of titanium alloys: A brief review. J. Alloys Compd. 965, 171030 (2023).

Genc, O. & Unal, R. Development of gamma titanium aluminide (γ-TiAl) alloys: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 929, 167262 (2022).

Ye, C. et al. Dynamic response and microstructure evolution of titanium alloy plates under low-velocity impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 180, 109888 (2022).

Zeng, S. & Li, F. Research status of aluminum base coating on titanium alloy. Coatings 13, 1525 (2023).

Ullah, Z. A. et al. A review on laser cladding of high-entropy alloys, their recent trends and potential applications. J. Manuf. Process. 68, 225–273 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Research and progress of laser cladding on engineering alloys: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 66, 341–363 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Recent research and development status of laser cladding: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 138, 106915 (2021).

Pan, C. et al. Synthesis and properties of Ti-Al coating by high-frequency induction heated combustion. J. Alloys Compd. 939, 168739 (2023).

Zhang, H. X. et al. Effect of Y2O3 on microstructures and wear resistance of tic reinforced Ti-Al-Si coating by laser cladding on TC4 alloy. Surf. Rev. Lett. 26, 1950077 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Effect of SiC content on microstructural evolution and tribology properties of laser-clad TiC-reinforced Ti-Al-Si composite coatings. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 106019 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. The wear behavior of the laser cladded Ti-Al-Si composite coatings on Ti-6Al-4V alloy with additional tic. Materials 14, 4567 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. Effect of chromium content on microstructure, hardness, and wear resistance of as-cast Fe-Cr-B alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 28, 6428–6437 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of Cr2O3 on the microstructure and wear resistance of coatings prepared from Cr2O3-SiC-Al composite powders. Mater. Chem. Phys. 304, 127860 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Investigation into corrosion and wear behaviors of laser-clad coatings on Ti6Al4V. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 016587 (2020).

Aghili, S. E. et al. Microstructure and oxidation behavior of NiCr-chromium carbides coating prepared by powder-fed laser cladding on titanium aluminide substrate. Ceram. Int. 46, 1668–1679 (2020).

Lu, S. et al. Effect of V and cr transition layers on microstructure and mechanical properties of Ni-based coating on titanium alloy fabricated by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 405, 126734 (2021).

Thomas, J. et al. Additive manufacturing of compositionally graded laser deposited titanium-chromium alloys. Additive Manuf. 33, 101132 (2020).

Han, T. et al. Effect of cr content on microstructure and properties of Ni-Ti-xCr coatings by laser cladding. Optik 179, 1042–1048 (2019).

Yu, Q. et al. Influence of Cr/Mo ratio on microstructure and mechanical properties of the Ni-based superalloys fabricated by laser additive manufacturing. J. Alloys Compd. 894, 162484 (2022).

Huang, K. & Huang, W. Microstructure and wear resistance of Ti5Si3/Ti3Al composite coatings prepared by laser cladding on TA2 titanium alloy. Lubricants 11, 213 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. Microstructure and wear resistance of laser cladding Ti-Al-Ni-Si composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 445, 128727 (2022).

Sui, X., Lu, J. & Zhang, W. Morphology: Microstructure and improved mechanical properties of TiB2/TiB/TiN reinforced Ti3Al matrix composite coating with ZrO2 addition. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 29, 510–519 (2020).

Bagheri-Sadeghi, N. & Helenbrook, B. T. Buoyancy and Marangoni effects on horizontal ribbon growth. J. Cryst. Growth. 596, 126822 (2022).

Watanabe, Y. et al. Grain refinement of stainless steel by strontium oxide heterogeneous nucleation site particles during laser-based powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 308, 117700 (2022).

Falodun, O. E. et al. The effect of TiN-TiB2 on the microstructure, wear, and nanoindentation behavior of Ti6Al4V-Ni-Cr matrix composites. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 32, 5566–5575 (2023).

Duan, F. et al. Mechanical behavior and dynamic damage constitutive model of glass fiber-reinforced vinyl ester with different fiber contents. J. Sci. Progress. 103, 1–24 (2020).

Feng, Z. C. et al. Microstructure and high temperature reciprocating sliding wear properties of MoSi2/TiC/γ-Ni composite coating in-situ synthesized by co-axial powder feeding plasma transferred Arc cladding. Tribol. Int. 129, 82–91 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. On the enhanced wear resistance of laser-clad CoCrCuFeNiTix high-entropy alloy coatings at elevated temperature. Tribol. Int. 174, 107767 (2022).

Lifan, S. & Dejun, K. Microstructure and friction–wear performance of laser cladded Cu10Al–Ti–MoS2 coatings under oil lubrication condition. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 75, 57–67 (2022).

Bao, Y. et al. Wear resistance of TiB/Ti composite coating fabricated by TIG cladding using Ti-TiB2 cored wire. Surf. Coat. Technol. 474, 130086 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. High power Arc ion plating of Thick Cr2N hard coating on Ti-based alloys: oxidation and wear behaviors. Surf. Coat. Technol. 448, 128924 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Hefei Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. HZR2432), the University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province (No. GXXT-2023-025), University Natural Science Research Program of Anhui Province (No. 2023AH040036), and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Anhui Jianzhu University (No. 2024QDHZ07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L.: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Y.G.: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. J.L.: Formal analysis, Resources, Funding acquisition. L.C.: Investigation, Supervision, Resources. L.W.: Investigation, Supervision, Project administration. H.S.: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation. P.W.: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Guo, Y., Lei, J. et al. Effect of chromium addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of laser cladding Ti-Al-SiC composite coatings. Sci Rep 15, 39481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23071-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23071-2