Abstracts

In the process of user emotion-oriented product development, emotion perception has become a crucial dimension in evaluating product design. Aiming to address the issues of subjectivity bias and insufficient efficiency in multi-source information fusion in existing methods, this study proposes a hybrid product evaluation framework that integrates a back-propagation (BP) neural network and an improved Dempster-Shafer (D-S) evidence theory. The method constructs input vectors by combining product design features and user features. It utilizes multilayer BP networks to learn the nonlinear mapping relationship between product attributes and user emotions, thereby generating preliminary emotion perception probability assignments (BPA). To further address the issue of conflicting expert opinions, a weighting strategy based on the average distance of the evidence is introduced, and the D-S evidence fusion process is optimized. Ultimately, the improved evidence theory model can effectively unify the judgments of multiple experts and output a unified emotional evaluation result. The empirical study, with the sofa as the research object, shows that the proposed method can effectively identify key design elements and achieve quantitative evaluation in the emotional dimension. Through comparative experiments, this method demonstrates higher stability and adaptability in multi-source data processing and fusion accuracy, as well as good scalability, providing quantitative decision support for user-centered product design practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of the rapid development of modern society, the manufacturing industry is constantly evolving, and user demand is also presenting a trend of diversification and personalization1. Consumers’ expectations of products have long exceeded the single functional dimension and have shifted to the pursuit of integrated experiences that balance function, quality, and emotional value. Whether a product can stimulate the user’s emotional resonance often depends on the emotional imagery it conveys. What users consume is no longer just the practical product itself, but also the entertainment, personality expression, and other emotional added value it contains. Therefore, to guide product design more effectively, there is an urgent need to develop an evaluation strategy that can recognize and quantify users’ emotional responses, thereby understanding the real feedback of the user community on the product at an emotional level.

In the context of complex systems engineering, product design is not only a process of technological innovation, but also an embodiment of the dynamic balance between value synergy and user needs2. As a comprehensive optimization problem oriented to multi-objective and multi-constraints, the product evaluation system directly affects the selection of design solutions and life cycle performance3. However, existing studies have shown that traditional multi-objective decision-making methods have significant shortcomings in addressing complex product evaluations. For example, although the hierarchical analysis method (AHP) proposed by Saaty et al.4 is widely used in structured decision making, it is highly dependent on the subjective judgment of experts. It is susceptible to cognitive bias, particularly when evaluating emotional or subjective aspects. Kendall’s correlation coefficient is generally lower than 0.7, which results in poor stability of the evaluation results. In addition, although objective assignment methods (e.g., entropy weighting or CRITIC method) can overcome some of the subjectivity, their nature relies on numerical structured data, which makes it challenging to capture the implicit emotional needs and semantic information of users, which in turn leads to decision-making bias in multimodal data environments5.

With the development of emerging interdisciplinary disciplines such as Design Anthropology (Design Anthropology) and Kansei Engineering (Kansei Engineering), more and more researchers have tried to incorporate users’ emotions and perceived experiences into the product evaluation system. For example, Liang et al.6 analyzed the styling design of household scales based on hierarchical analysis, aiming to clarify the relationship between emotional intent and design considerations. Hassenzahl et al.7 further proposed that the traditional function-oriented product development paradigm is gradually shifting to an emotional value and experience-driven design framework. At the same time, data-driven research on emotional evaluation is also gradually emerging. Jin et al.8 have based their work on the combination of the Kano model and an emotion word mining product evaluation method, which effectively improves the responsiveness of product design to the potential needs of users. This is even though effective product evaluation methods have been evolving in recent years, and in particular, positive advances have been made in user perception modeling and expert validation. However, the current product evaluation model still faces two core bottlenecks: first, the lack of a scalable fusion framework to systematically integrate user perceptual feedback and expert rational judgment, resulting in a break between subjective and objective emotional evaluation results, and unable to support design decisions effectively. Second, in the face of high-dimensional, unstructured, multi-source heterogeneous data, the existing models generally suffer from insufficient nonlinear modeling capabilities and weak evidence conflict handling mechanisms, which in turn affect the consistency and stability of the evaluation system.

Aiming to address the above challenges, academics have conducted numerous research studies on multi-source information fusion and nonlinear decision modeling in recent years. For example, Li et al.9 introduced deep learning technology to recognize the sentiment of product forms and user evaluation data using a convolutional neural network (CNN), which significantly improves the processing capability of unstructured data. Zhu et al.10, on the other hand, combined Fuzzy AHP and TOPSIS methods to construct a reliable multi-attribute decision-making framework under fuzzy uncertainty. In addition, Zuo and Wang11 comprehensively determined the evaluation indexes based on perceptual engineering (KE). They employed the hierarchical analysis method (AHP) to establish the overall evaluation system for the product, thereby developing a chair evaluation model centered on consumer perception. The Human-Centered Design (HCD) framework proposed by Van and Dorst12, although excellent in improving user experience (resulting in a 19% increase in NPS), lacks sufficient support for multi-objective optimization that includes rational metrics such as cost and performance. From a comprehensive point of view, although existing research has made much progress in emotion-driven, collaborative optimization and AI-assisted evaluation, there is still much room for improvement in how to effectively integrate the perceptual cognition of the user community with the professional judgment of the design experts, and to maintain the consistency of decision-making under a high-uncertainty environment.

In summary, this study has established a ‘dual-layer evaluation integration pathway’ (data-driven learning—uncertainty modelling—conflict-weighted optimisation), achieving a synergistic breakthrough in both theory and practice within the field of product sentiment evaluation. Unlike previous research that relied solely on expert judgment or lacked effective multi-source conflict resolution mechanisms, this study proposes an innovative framework that combines a backpropagation neural network with an enhanced version of De Finis’s evidence theory. BP neural networks possess formidable nonlinear learning capabilities, enabling them to capture intricate mapping relationships between user characteristics and product attributes. The enhanced D-S evidence theory, through its conflict-weighted fusion strategy, elevates the consistency and robustness of expert evaluation outcomes. The integration of these two approaches not only achieves effective synergy between data-driven learning and uncertainty modelling but also establishes a methodological foundation for constructing scalable, adaptive sentiment-oriented product evaluation systems.

The principal contributions of this study are threefold:

-

1.

A multi-source feature product evaluation system integrating BP neural networks with De Finis-Sawyer evidential theory has been proposed. This constructs a probabilistic mapping between user perceptions and expert judgements, forming a dynamic, adaptive sentiment evaluation metric system that enhances the scientific rigour and predictive accuracy of assessments.

-

2.

A closed-loop mechanism has been established, linking user perception to design decisions and translating user emotional responses into design rationale. This approach ensures the rationality and consistency of multi-objective decision-making, effectively preventing the erosion of product value.

-

3.

A three-stage collaborative evaluation model has been constructed, systematically integrating user data with expert knowledge to optimise the emotional mapping process of design elements. This provides actionable methodological support for emotional modelling and decision-making.

It should be noted explicitly that the affective perception framework proposed in this study does not derive directly from traditional psychological affect models (such as the Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance model or affective engineering), but is constructed based on a mature methodological paradigm combining BP neural networks with D-S evidential theory. This combination has been extensively validated in fields such as fault diagnosis, image recognition, and multi-source information fusion. By transferring this modelling paradigm to the domain of product affective evaluation, this research not only overcomes the limitations of traditional affective models in processing high-dimensional heterogeneous data but also expands the application boundaries of the BP–D-S hybrid method within user-centred design research.

Methods

BP neural network

The BP neural network was first proposed by Rumelhart et al.13 in 1986, which systematically elaborated the back-propagation algorithm. It was applied to solve nonlinear classification and learning problems, especially to realize complex pattern mapping through multi-layer neural networks.

Structurally, a BP neural network consists of input, hidden, and output layers, each with nodes. Weights connect the nodes in neighboring layers, but the nodes within each layer are independent of one another. Theoretically, it has been demonstrated that BP neural networks with two hidden layers can approximate arbitrary nonlinear functions with arbitrary accuracy14,15,16,17. In practical applications, the BP neural network with two hidden layers also meets the computational needs well18,19.

BP neural networks have been widely validated in several research areas due to their good adaptive ability in nonlinear modeling and data fitting. For example, Fei et al.20 significantly improved indoor localization accuracy based on WiFi fingerprints by introducing an improved BP neural network. Zhang et al.21 developed a BP neural network model for predicting the heat transfer pressure drop of heat exchangers and optimized it using a genetic algorithm. Chen et al.22 fused a BP neural network with a genetic algorithm in a fabric defect detection task and achieved an average recognition accuracy of 94.57%. Wang et al.23 quantitatively evaluated the impact of the epidemic on carbon emissions based on the fusion method of a BP neural network and an ARIMA model, and the results revealed that the carbon emission reduction effect in developing countries was underestimated by approximately 5%.

Additionally, BP neural networks demonstrate good modeling capabilities in product evaluation. Yi et al.24 proposed a BP neural network model incorporating genetic algorithms to solve the matching problem between parts enhancement and machine testing. Dan et al.25 constructed a color emotion evaluation model by combining eye-movement and electroencephalogram data to quantify users’ color preferences for electric irons accurately. Xu et al.26 developed a T-shirt style evaluation model using BP neural network modeling of users’ perceptual imagery, generating five optimal design solutions to achieve accurate matching of users’ preferences. Cai et al.27 proposed a wheelchair form emotion prediction model that combines the Gray Wolf optimization algorithm and BP neural network, which quantifies the association between design elements and users’ perceptual needs, thereby significantly improving the degree of emotional matching. Liang et al.28 combined the artificial fish swarm algorithm and the BP neural network to propose an aesthetic value assessment model for digital cultural and creative products, which enhances the convergence efficiency of the algorithm while achieving higher precision in emotional assessment.

The operational framework of the BP neural network is shown in Fig. 1. First, the network topology is determined, including the number of nodes in the input, hidden, and output layers, as well as the weights and thresholds, which are then initialized. Subsequently, the network initiates forward propagation, passing information sequentially from the input layer to the output layer, and calculates the current output result. Next, the error between the actual output and the desired output is calculated, and the error information is passed back layer by layer through the back-propagation algorithm, which is used to adjust the weights and thresholds of each layer dynamically. The process continues to loop and iterate until the error meets the preset requirements or reaches the maximum number of iterations, thus obtaining the optimal parameters. Finally, the trained network is used to predict the test samples and output the corresponding results.

The operation mechanism of BP neural networks is divided into two main parts: the forward transfer of network input information and the backward propagation of network computational errors.

The forward transfer of network input information (input layer—output layer) is mathematically expressed as follows:

The output of the ith node of the input layer is: xi.

The output of the jth node of the hidden layer is:

where \(y_{j} = f_{1} (v_{j} )\) denotes the output of the jth node of the implicit layer.

The output of the kth node of the output layer:

where \(y_{k} = f_{2} (v_{k} )\) denotes the output of the kth node of the output layer.

The back-propagation of network computational error information (output layer—input layer) is mathematically expressed as follows:

The BP neural network is more widely used in various fields due to its ability to perform nonlinear mapping, self-learning, generalization, and fault tolerance29,30. It does not need to establish an explicit mathematical model in advance, can automatically extract potential laws by learning from a large number of samples, and has good extrapolation ability for unknown samples, while still maintaining strong robustness when some inputs are abnormal. However, BP neural networks also have certain limitations, such as the lack of effective criteria for the selection of the learning rate, slow convergence speed, susceptible to the influence of the gradient disappearance, and due to the dependence on the gradient decline of the error, it is easy to fall into the local minima, and it is not easy to achieve the global optimum, which affects the fitting accuracy and generalization performance of the model. Therefore, in order to further improve the accuracy and robustness of multi-source information fusion in the process of sentiment evaluation, this paper introduces the “D-S Evidence Theory based on Average Evidence Distance Improvement” to alleviate the decision-making distortion due to the conflict of experts’ opinions, and to enhance the stability and credibility of the evaluation model under the complex evaluation scenarios.

Improving D-S evidence theory based on mean evidence distance

Dempster first proposed d-S evidence theory in 196731, and was systematically extended on this basis by his student Shafer in 1976, forming a more complete set of mathematical theories for dealing with uncertainty problems. The theory has a wide range of applications in the field of multi-source information fusion. In recent years, D-S evidence theory has been applied to several practical scenarios. For example, Feng et al.32 combined D-S evidence theory with various deep learning models to construct an air quality level prediction model, which effectively improved the prediction accuracy. Yang et al.33 proposed a drilling fault diagnosis method that combines pattern decomposition and D-S evidence theory, thereby improving the fault detection ability under complex working conditions. Li et al.34 developed the Multi-Discount Contextual Information Inconsistency Elimination (MDCIE) algorithm, based on the D-S evidence theory, to address the problem of frequent inconsistencies in multi-source information in smart home environments. This approach significantly improves the robustness and reliability of multi-source information fusion. In summary, the D-S evidence theory often shows significant effects in dealing with situations where multi-source information is often inconsistent. Therefore, this paper adopts D-S evidence theory as the primary method for multi-source information fusion in product evaluation to enhance the synergistic consistency between expert evaluations and user perceptions.

In The D-S evidence theory, it is assumed that the space 2Θconsists of all subsets of a nonempty set \({\Theta } = \{ \theta_{1} ,\theta_{2} , \cdots ,\theta_{n} ,\}\), see Eq. (4).

The propositions in the nonempty set Θ are mutually exclusive and form a complete set containing all possible hypotheses for a given problem. The underlying probability distribution defined on Θ is a \(2^{{\Theta }} \,[0,1]\) function m, called the mass function, and satisfies Eq. (5).

where m(A) is the underlying probability assignment for proposition A and indicates the degree of support for the occurrence of proposition A from the evidence.

Let m1, m2, …, mn be the basic probability assignments on the hypothesis space 2Θ, then the Dempster synthesis rule in the D-S evidence theory, see Eq. (6).

where \(K \in [0,1]\) is the conflict factor, which also becomes a normalization constant, and is obtained through Eq. (7).

Through continuous application and practice, the traditional D-S evidence theory gradually reveals its deficiencies in two aspects. First, the method of determining the base probability assignment (BPA) lacks a unified standard across different application scenarios and generally relies on expert experience for assignment, which is susceptible to subjective cognitive bias and thus reduces the objectivity and stability of the model. Second, when there is highly conflicting multi-source evidence, D-S evidence fusion tends to output unreasonable results, leading to decision-making distortion. This problem is particularly prominent in practical applications, which seriously affects the validity and reliability of the model in complex environments.

To address the above problems, BP neural networks are introduced in this study to optimize the basic probability assignment (BPA). BP neural networks, due to their excellent nonlinear mapping ability, can autonomously extract deep associations between input features and affective perceptions by learning from large-scale user evaluation data, thus effectively overcoming the problem of traditional BPA, which is overly reliant on the subjective experience of experts. In addition to alleviating the integration bias caused by the high degree of conflict between evidence bodies, this study employs a weighting method based on the average evidence distance to dynamically adjust each evidence source, thereby enhancing the robustness and rationality of D-S evidence integration. Ultimately, through the improved Dempster-Shafer synthesis rule, the effective integration of expert opinion and user group cognition is achieved, providing more credible and stable decision support for the sentiment evaluation model. The average evidence distance weighting method is shown in Eqs. (8)-(10).

where di denotes the degree of difference in evidence of the ith expert; mi(A) denotes the basic probability assignment of the ith expert to proposition A; m(A) is the average probability assignment computed by all the experts to proposition A; and D represents the similarity matrix between subsets. Equation (9) is used to calculate the average probability assignment of the panel of experts to proposition A, where n is the total number of experts. ∑di denotes the sum of all experts’ evidence variances, which is used for normalization; and c(mi) is the weight calculated based on the average evidence distance, which is mainly used to weight and correct the basic probability assignment of each expert.

Product evaluation construction based on BP neural network-improved D-S evidence theory

Although both BP neural networks and D-S evidential theory have been extensively applied in fields such as fault diagnosis, pattern recognition, and multi-source decision-making, their separate application to product evaluation still exhibit significant limitations. BP neural networks can effectively learn the nonlinear mapping between inputs and emotional responses, yet they lack mechanisms to address the issue of expert disagreement. Conversely, while traditional D-S evidential theory provides a mathematical framework for uncertainty fusion, it often leads to distorted results in high-conflict scenarios due to its reliance on subjective probability distributions.

The theoretical innovation of this study lies in integrating both approaches to construct a unified framework for affective decision-making. Specifically, the BP neural network generates objective basic probability distributions (BPA) by learning from large-scale user data, thereby reducing reliance on expert-assigned values. Building upon this foundation, a weighted refinement of D-S evidential theory based on average evidence distance is introduced. This dynamically adjusts the weighting of expert opinions, thereby mitigating conflict bias and enhancing the stability of the information fusion process. This hybrid approach ensures both the predictive capability of data-driven learning and the reliability of multi-expert consensus—a breakthrough that has not been previously systematically achieved in product evaluation models.

Evaluation process

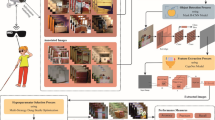

The product evaluation framework, based on a BP neural network-improved D-S evidence theory, is shown in Fig. 2. First, a complete dataset is constructed by collecting information on product features, sentiment evaluation scores of different design elements, and user characteristics. The BP neural network is then trained using this dataset. On this basis, the experts’ emotional evaluation of the product is input into the BP neural network to generate the basic probability distribution function in D-S evidence theory. Subsequently, an improved D-S evidence fusion method based on average evidence distance weighting is employed to integrate evaluation information from multiple experts effectively. Eventually, the model outputs the comprehensive evaluation index of the product’s emotion, or identifies the design elements that need to be optimized and the corresponding improvement priorities.

In this paper, user characteristic information is combined with user evaluation data of products to train BP neural networks, thereby fully considering the influence of user differences on the emotional evaluation of products during the generation of basic probability assignments. By taking the evaluation data of the user group as an objective basis and training the BP neural network, the expert’s emotional evaluation of the product can be transformed into the basic probability assignment function in the D-S evidence theory, realizing the effective integration of the user’s objective cognition and the expert’s subjective judgment. Subsequently, the D-S evidence fusion process is optimized by weighting each base probability distribution function based on the average evidence distance, which improves the rationality and accuracy of information integration. Eventually, the model can output an emotionally comprehensive evaluation index of the product and identify the design elements that need to be optimized, along with the corresponding improvement index. This provides powerful data support and a decision-making basis for the positive design of the product.

Product characteristics and user characteristics construction

In this study, a large dataset of product images and user review data is obtained from mainstream e-commerce platforms and related specialized websites using Python web crawler technology. For the crawled images, Photoshop is used for image optimization processing to enhance the clarity and usability of the samples. In addition, for the text comment data, standardized cleaning, denoising, word splitting, and sentiment label extraction are carried out to ensure that the data has high analysis quality. Subsequently, representative and highly emotionally relevant samples are retained through multiple rounds of screening to provide a solid data foundation for subsequent sentiment evaluation studies.

At the same time, to enhance the scientific rigor and adaptability of feature modeling, this study employs the expert interview method, inviting several industry experts with extensive practical experience. Based on the market research data and the results of the in-depth expert interviews, the user group characteristics of the target products are meticulously categorized, and combined with the expert consensus, the product design elements of the typical samples are systematically deconstructed, and the feature level of each design element is clarified (see Table 1and 2), to provide feature support for the subsequent emotion modeling and analysis.

BP neural network structure and training

Number of network layers and nodes

Given the good nonlinear fitting ability of the BP neural network, according to the universal approximation theory, a three-layer BP neural network can approximate any nonlinear continuous function with arbitrary accuracy and realize the mapping from an n-dimensional space to an m-dimensional space35. However, for the high-dimensional features and complex nonlinear relationships involved in product sentiment evaluation in this study, to further improve the feature extraction ability and expression ability of the model, this paper adopts a four-layer BP neural network structure with two hidden layers (shown in Fig. 3).

Each training sample comprises 14 feature dimensions: five design elements (I1–I5), four user characteristics (X1–X4), and five user sentiment alignment scores. Consequently, the backpropagation neural network used to map user/product features to sentiment probabilities possesses an input layer with 14 nodes.

Regarding the configuration of hidden layer nodes, as no unified theoretical formula currently exists to provide precise guidance, the selection of node count must strike a balance between fitting accuracy, training efficiency, and generalisation capability. An excessive number of hidden layer nodes may enhance the model’s fitting capacity but will significantly increase computational overhead and potentially lead to overfitting. Conversely, an insufficient number of nodes may result in inadequate model fitting capability or even prevent effective convergence. Following multiple rounds of experimental optimisation, the number of nodes in the first hidden layer was ultimately determined to be 10, with the second hidden layer comprising eight nodes. This architecture ensures robust modeling of complex, nonlinear relationships while maintaining favorable performance in terms of training speed, convergence, and generalization capability.

Learning rate selection and initialization of connection weights and thresholds

The learning rate is a crucial hyperparameter that significantly impacts the training performance of BP neural networks. If the learning rate is set too small, although it can ensure the smoothness of the training process, it will lead to slower network convergence and a significant increase in training time. On the contrary, if the learning rate is set too large, although it can accelerate the training speed and improve convergence, it is easy to cause the network to exhibit gradient oscillations during the training process, and even fail to reach the global optimal solution. To address the above problems, a common approach is to use a dynamically adjusted variable learning rate strategy, i.e., a larger learning rate is used at the beginning of training to enhance the convergence speed. Then the learning rate is gradually reduced with the depth of training to ensure the stability of the training process and avoid oscillations. To strike a balance between training speed and model stability, the learning rate of the BP neural network is set to 0.05 in this study.

After hyperparameter tuning, the final BP network architecture consists of two hidden layers with 10 and 8 neurons, respectively (see Table 3 for full settings). Training uses a learning rate of 0.05, with a maximum of 500 iterations, and weight initialization in the interval [0, 1] (consistent with our implementation). Table 3 summarizes all key hyperparameters for reproducibility 3.

D-S theory of evidence evaluation convergence

The results obtained by BP neural cannot be used directly for the synthesis of the evidence theory; it is necessary to normalize the probability vector obtained from the prediction to obtain the basic probability vector, which is the basic probability assignment of the proposition for the evidence.

The prediction results of the BP neural network are normalized, and the results obtained after normalization are synthesized using the improved DS evidence theory. The formula for normalization can be expressed as:

Assuming that the rate vector obtained by the BP neural network after predicting five pieces of data for each object is V. \({\text{V}}_{{\text{i}}} = ({\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}1}} ,{\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}2}} ,{\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}3}} ,{\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}4}} ,{\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}5}} )\), Where \({\text{V}}_{i} = \frac{{{\text{V}}_{i} }}{\sigma }\), such that \({\text{m}}_{{\text{i}}} ({\text{A}}_{{\text{i}}} ) = {\text{a}}_{{{\text{i}}1}}\), \({\text{i}} \in (1,2,3,4,5)\), \({1} \in (1,2,3,4,5)\) denotes the elemental evidence that the product is judged to be in need of improvement.

The synthesized formulas are shown in Eqs. (12) and (13).

The first data will be taken from each object to be predicted by the neural network to get a number between [0, 1]. Then the data obtained from each BP network will be normalized to get the basic probability assignment of that piece of evidence to that proposition.

Experimental results and analysis

As an indispensable piece of furniture within the domestic living space, the sofa has become deeply integrated into the daily routines, leisure activities, and social interactions of the household. With rising living standards and the continuous evolution of aesthetic sensibilities and consumer attitudes within families, users’ demands for sofas are gradually shifting from traditional functional considerations towards a greater emphasis on emotional experience and spatial aesthetics. Design aesthetics, personalised expression, material texture, and harmony with the interior environment are increasingly becoming key factors of concern for consumers. Against this backdrop, there is an urgent need to establish a scientifically sound and rational product evaluation strategy. This will enable a deeper understanding of users’ perceptions and emotional needs regarding sofas, thereby providing adequate support for informed decision-making and optimising positive design and innovation. To this end, this study proposes a product evaluation strategy integrating BP neural networks with D-S evidential theory. Its effectiveness and applicability have been validated through extensive user research and experimentation.

This study selected sofas as the experimental subject based on three primary considerations: Firstly, as a quintessential experiential household consumer product, sofas evoke significant emotional responses during use, encompassing dimensions such as comfort, aesthetics, material texture, and spatial harmony. Consequently, they aptly reflect the core issues of product emotional design. Secondly, sofas possess abundant review data on mainstream e-commerce platforms, facilitating access to high-quality subjective user evaluations and multimodal information to meet the data requirements for affective modelling. Thirdly, the core design elements of sofas—colour, material, texture, form, and dimensions—encompass multidimensional affective factors, enabling comprehensive testing of the model’s applicability and robustness under multi-source input conditions.

Emotional evaluation vocabulary identified

Consumer reviews and evaluations of products have important reference value. Through the sentiment analysis of consumer reviews, the emotional tendency of the product and user satisfaction can be obtained8. Sofas, as one of the home furnishing products, have a large number of user reviews on major e-commerce platforms. Through sentiment analysis of these reviews, the emotional feelings and feedback of consumers on sofas can be understood.

For data collection, this study scraped samples from multiple mainstream e-commerce platforms using the keyword ‘sofa’, with a depth of the first five pages, yielding a total of 3,798 reviews. After cleaning and noise reduction, 3,498 high-quality data points were retained. Image samples underwent three rounds of screening, ultimately yielding 20 representative sofa samples covering different price points, brands, and styles. At the expert level, five specialists with design backgrounds were invited to conduct scoring. At the user level, 478 valid responses were collected through questionnaire surveys, encompassing diverse attributes such as age, gender, usage scenarios, and preference patterns. Through multi-platform collection, multi-round screening, and multi-source integration, the diversity and representativeness of the samples were ensured.

Data pre-processing

Commodity evaluation data often contains a large amount of redundant or non-valuable information, such as default evaluations automatically generated by the system and repetitively pasted content. To improve data quality, it is necessary to thoroughly clean and optimize the acquired commodity evaluation dataset, which primarily involves removing deactivated words and standardizing text (as shown in Table 4).

Word frequency statistics for emotional words

After completing the preprocessing work, including cleaning, denoising, and standardization of the text data, the processed comment data is used as input to call the Gooseeker Sentiment Analysis API for automated analysis of the text sentiment. The API is based on a large-scale natural language processing model, which can effectively identify the sentiment polarity in the comments and extract keywords or phrases with significant sentiment tendencies. Through sentiment analysis, 988 words with significant emotional tendencies were initially extracted from the review data. These words encompass users’ subjective evaluations of sofas in multiple dimensions, including functionality, comfort, aesthetics, material quality, and spatial suitability, which fully reflect users’ emotional feedback during the actual use process.

To extract more representative core emotion words, the K-means clustering algorithm was used to analyze the similarity clustering of these 988 words. During the clustering process, the cosine similarity between word vectors is calculated to group semantically close words into the same category. Through multiple rounds of clustering effect validation, the final number of clusters is determined to be 67, obtaining 67 high-frequency and representative emotion words that are highly relevant to sofa products. These words not only cover users’ rational cognition of the functional attributes of sofas but also reflect users’ subjective evaluation of aesthetics, emotional resonance, and usage experience.

Conduct word frequency statistics on the emotion words obtained through clustering and sort them according to frequency. Some of the word frequency statistics results are shown in Table 5. According to the results of 5, it can be known that “comfort” is the most frequently used emotional word, and “comfort” is also one of the typical emotional need keywords in Kansei Engineering. Therefore, it is considered the target emotional image word for subsequent research on product emotional design.

Sofa product sample construction and user characteristics classification

We utilize a Python web crawler tool to conduct data collection for major e-commerce platforms (e.g., Amazon, Walmart, Wayfair, IKEA) and related furniture design websites. A total of 3798 sample images of sofa products were crawled. During the preliminary screening stage, invalid samples with quality issues, such as duplicates, overexposure, blurred images, shooting angle deviations, and cluttered backgrounds, were removed, and 349 valid images were retained.

To further improve the quality of the samples, image processing software such as Photoshop was used to de-background the screened images, thereby eliminating the interference of the complex background on subsequent analysis. In this process, images with poor preprocessing effects were eliminated, and 96 high-quality couch sample images were finally retained.

To ensure that the selected samples have a high value in product emotional design research, expert interviews were conducted for in-depth screening. Several furniture designers and market experts with extensive experience in the industry were invited to select 20 representative sofa product samples based on multidimensional criteria, including market trends, design styles, and user preferences (see Fig. 4). These representative samples were analyzed by systematic deconstruction of design elements and feature levels (see Table 6 for the analysis results).

In addition, combining market research data and expert interviews, the detailed classification of user characteristics is completed with respect to the consumption needs and behavioral characteristics of current mainstream sofa users. The classification results are presented in Table 7.

Feature coding of sofa samples and BP neural network training

The 20 representative sofa samples screened in the preliminary stage are feature-coded, and the specific coding rules are presented in Table 6. Subsequently, four sofas are randomly selected from them as the objects of subsequent expert sentiment evaluation for probabilistic assignment generation and fusion of D-S evidence theory. The remaining 16 sofa samples serve as the basis for constructing the user perception data training set.

Based on these 16 samples, a questionnaire was designed and distributed on the emotional perception of sofas. The questionnaire is centered on five core design elements (Color (I1), Materials (I2), Textures (I3), Typology (I4), Dimension (I5)) and four user characteristics (Age (X1), Gender (X2), Application (X3), Usage Features (X4)). A total of 478 valid data samples were collected and collated from the questionnaire. To ensure the model’s generalization ability, the dataset is divided into a training set and a testing set in a 4:1 ratio.

Each data sample contains 14 feature dimensions, including five design elements coded for the sofa, four user characteristics coded for the sofa, and the users’ emotional fit scores for these five design elements. The scores are based on a Likert scale from 1 to 10, with one representing "not at all in line with emotional expectations" and 10 representing "fully in line with emotional expectations."

The BP neural network was trained based on user cognitive data collected from the questionnaire, combined with samples labeled by experts. The key setup parameters of the BP neural network are detailed in Table 3. After the construction of the BP neural network structure was completed, the model was trained using the training set to preliminarily obtain a neural network model for generating the Base Probability Assignment (BPA).

Basic probability assignments

The identification framework of sofa design elements that need improvement, constructed in this study, includes a total of six categories: color (I1), texture (I2), material (I3), shape (I4), size (I5), and normal (N). Among them, “Normal (N)” indicates that the current design does not require optimization for that element.

In the experimental stage, four sofa products were randomly selected as evaluation objects. Two furniture product designers with extensive practical experience and three graduate students in the field of product design, totaling five experts, were invited to evaluate the emotional fit of the five core design elements for each sofa. The characteristic information of the five experts and the characteristics of the corresponding design elements of the four sofas were also counted, as shown in Tables 8, 9 and 10.

Subsequently, the emotional evaluations provided by the five experts, based on each design element, are integrated with the design feature information of the corresponding sofa samples in Tables 6 and 7, serving as the input data for the BP neural network. Through model training and forward computation, a total of 20 sets of output results (i.e., four sofas × 5 experts) can be obtained for each sofa under each design element dimension. After normalizing the output results, the Basic Probability Assignment is generated. The specific results are shown in Table 11 and Fig. 5. This process effectively combines the subjective emotional judgment of experts with the objective design attributes of sofa products, and constructs a quantitative channel from “product features—expert evaluation—emotional mapping”, which provides basic data support for the subsequent multi-source information fusion based on the improved D-S evidence theory.

Improving the integration of D-S evidence theory for sentiment appraisal

For the four different sofa samples, the BP neural network outputs the BPAs shown in Table 11, based on the emotional evaluation of the products by five experts. Based on these results, the improved D-S evidence theory is further introduced to fuse the emotional evaluation results of the experts. The fusion process is carried out according to the Following Equations. (6) to (10), which achieves the unified integration of subjective judgments from multiple experts within the framework of objective emotional cognition of user groups, and the final fusion results are presented in Table 12.

In Table 12, the fundamental probability value of each design element reflects the degree of support for improvement of the element on the sentiment dimension, which is defined as the “improvement index”. The higher the probability value, the more urgently the design element needs to be optimized; conversely, it indicates that the design relatively meets the emotional expectations of users. Suppose the probability values of the five design elements are significantly lower than Mass(N). In that case, it can be considered that the overall emotional design of the product does not need significant optimization. Mass(N) represents the comprehensive index of emotional satisfaction, reflecting the overall degree of user emotional identity of the product.

As can be seen from Table 12, the sofas corresponding to Sample 9 and Sample 14 perform well in the emotional dimension of “comfort”, and the evaluation results of the five design elements reach a high level, with the composite indexes of 94% and 95% respectively, which indicates that the overall design of the sofas meets the emotional expectations of users well. In contrast, Sample 20 sofas exhibit a significant lack of performance in the ‘Texture’ design element, with an improvement index of 79.6%, indicating that this is the most important emotional shortcoming to optimize in terms of user perception. Additionally, sofa model 2 underperforms in the “Color” dimension, with an improvement index of 13.2%, indicating that this design element is not practical in conveying the target emotional imagery.

Secondly, the experimental results (Table 12) clearly demonstrate that for the same product, the ‘improvement index’ (Mass value) obtained from different design elements exhibits differences of several orders of magnitude. Taking Sample 20 as an example, its ‘material’ (I₂) element achieved an improvement index of 79.6%, while the indices for other elements were extremely low. This strongly suggests: 1) The priority of sensory channels: For home furnishings like sofas, where ‘rest’ and ‘comfort’ are core functions, ‘haptic’ sensation constitutes the user’s most direct and fundamental experiential channel. Consequently, the emotional weight associated with tactile associations evoked by ‘material’ – such as texture, warmth, and softness – inherently surpasses that of visual impact from “colour” or aesthetic perception from ‘form’. The high improvement index in the model’s output essentially renders explicit the sensory priorities residing in users’ subconscious. 2) Ambiguity and conflict in emotional semantics: Certain design elements (such as “colour”) exhibit greater polysemy and cultural dependency in their emotional connotations (e.g., red may signify both passion and warning). When experts evaluate these elements, significant divergence in opinions (i.e., conflicting evidence) is likely to arise. In contrast, the semantics of ‘material’ are more straightforward (e.g., ‘velvet’ evokes ‘luxury,’ while “linen” suggests ‘naturalness’). Our refined D-S evidence theory effectively captures and reconciles this conflict through weighted average evidence distances. Elements exhibiting greater conflict have their individual evidence weights moderately reduced prior to fusion, thereby allowing the opinions of higher-consensus elements, such as “material”, to be emphasized. This explains why the refined instructions for key elements emerge with such clarity in the fused results.

The model’s output should no longer be a vague assessment of ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but rather a detailed diagnostic report. For instance, the diagnostic conclusion for Sample 20 is: the primary issue to address is ‘material’ (79.6%), followed by minor attention to ‘form’ (5%), while elements such as “colour” and ‘texture’ may be maintained as they are for the time being. This provides the design team with a scientific basis for decision-making, within the constraints of time, budget, and craftsmanship, enabling resources to be concentrated on key points that most effectively enhance user emotional satisfaction, thereby maximizing the return on investment (ROI) of design efforts. Therefore, the value of this model lies not only in "post-event diagnosis" but more significantly in "pre-event prediction". During the initial design phase, designers can construct various virtual proposals (i.e., combinations of different design element characteristics). By employing a trained BP neural network, they can rapidly predict emotional evaluation outcomes and compare the distribution of ‘improvement indices’ across different proposals. This enables designers to anticipate the potential emotional outcomes of diverse design strategies, thereby circumventing emotional shortcomings before production commences. They can proactively select design directions with superior emotional performance, truly achieving data-driven’ forward design’.

Our model utilises a backpropagation neural network to learn the intricate, non-linear interactions between design elements and emotional responses. For instance, a profound interaction exists between “colour” and “material”: pairing a vibrant hue (I₁) with an inexpensive material (I₂) may yield disastrous emotional evaluations. Conversely, the same colour paired with a premium material could produce a positive effect. The model captures this elemental “chemistry”, with its final output—the refinement index—reflecting the element’s overall emotional performance within the current design context, rather than its isolated value. This better aligns with the complexity of real-world user perception.

Model comparison validation

In Chapter 4, this study constructs a multi-source emotion fusion evaluation model based on BP neural network and improved D-S evidence theory, and takes a typical sofa product as the research object, realizes the comprehensive processing of user evaluation data and expert opinions, successfully identifies the design elements to be optimized, and verifies the application value of this method in emotion-driven product design.

However, although the experimental results of a single model can reflect the feasibility of the method, to fully assess the practical applicability and performance advantages of the model, a side-by-side comparison with the traditional fusion strategy is needed to confirm its improved effect in terms of accuracy, stability, and conflict handling. Therefore, this chapter introduces three mainstream D-S evidence fusion methods as the baseline model for comparison, namely: the traditional D-S fusion method, Murphy’s average fusion method, and Yager’s conflict processing method, and conducts a systematic comparison experiment with the “Improved D-S fusion method based on the average evidence distance weighting” proposed in this paper. A comparison experiment program is designed with three core indices: accuracy, conflict degree, and stability. The experimental process and evaluation system are as follows.

Experimental comparison methods

Accuracy evaluation

Accuracy is used to quantify the consistency of the fusion results with the expert consensus. To address the subjective nature of product sentiment evaluation, this study used the mean value of the five experts’ ratings as the baseline label (divided into two categories: “need to optimize” and “satisfied”). The five experts independently rated the five design elements of the sample on a scale of 1 to 10. The scores are normalized and input into a BP neural network to generate the basic probability assignment (BPA) function, and the five BPA vectors of each sample group are fused.

Accuracy (Acc) was calculated as:

where Ncorrect denotes samples matching the expert consensus label (majority vote of ≥ 3/5 experts).

Conflict degree evaluation

The conflict degree characterizes the degree of disagreement between multiple sources of evidence, and its conflict coefficient is calculated using Dempster’s rule of combination to compute the conflict coefficient of expert BPA pairs:

-

Record the average K-value of the four sample groups during the fusion process

-

Compare the performance of different methods in high conflict scenarios (expert score variance > 1.5)

Stability evaluation

Noise Injection Protocol was first performed to stability verify the robustness of the model to input perturbations, Expert scores were perturbed by adding Δs∼U(−0.5, + 0.5) (uniform distribution).

Robustness Quantification was then performed to reconstruct the BPA based on the perturbation data and repeat the fusion 50 times.

and calculate the standard deviation of the dominant decision probability as a stability metric:

where dk is the dominant probability output (e.g., moptimize) in the k-th trial.

Description of experimental prerequisites

To ensure that the comparison experiments are scientifically sound and comparable between methods, the following three prerequisites are set in this paper:

1) Unified data input and BPA construction method.

The input of all fusion methods comes from the output of the BP neural network trained in Chapter 4, which generates basic probability assignments (BPAs) based on product design features and user evaluation information. Each expert’s rating data is mapped into a BPA vector through normalization, and the uncertainty mass m(Θ) is retained according to the D-S theory to ensure the consistency and validity of the input source.

(2) Standardized Reference Evaluation Benchmarks.

Since there is no absolute truth value standard for emotion evaluation, this paper uses the weighted average result of five experts’ ratings as the reference standard, which serves as the basis for judging the accuracy of each fusion method. The evaluation results are categorized as “need to optimize” or “satisfied” to establish a unified classification and labeling system.

3) Consistent Perturbation Model and Implementation Environment.

To test the stability of each method, a perturbation of ± 0.5 was introduced to the expert scores, and the fusion process was repeated to statistically fluctuate the output. All methods are implemented in a Python environment, with fixed random seeds and no post-processing, to ensure repeatable experiments, controllable process, and fair and credible results.

Comparative experimental results and performance analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the “BP neural network fusion to improve D-S evidence fusion method” proposed in this study, we select four groups of previous sofa product samples and compare their accuracy, conflict, and stability performance under four typical fusion strategies. The experimental results are shown in Table 13:

According to Fig. 6, both traditional D-S and Murphy methods exhibit high conflict degrees, which can easily lead to fusion distortion. The Yager method can suppress the conflict to zero, but it sacrifices information resolution. In contrast, the method in this study effectively regulates the impact of conflict through the average evidence distance weighting strategy, which makes the fusion more stable and credible.

In Fig. 7, the output fluctuation of this paper’s method is minimized under a ± 0.5 noise perturbation, with an average standard deviation of 0.042. This significantly outperforms other strategies and demonstrates good robustness for highly subjective evaluation scenarios in emotion cognition tasks.

Through a comprehensive comparison of four fusion strategies—namely, traditional Dempster-Shafer (D-S) theory, Murphy’s averaging, Yager’s rule, and the proposed BP–D-S hybrid method—this study verifies the superior performance of the proposed framework across three critical dimensions: accuracy, conflict resolution, and robustness. Specifically, the proposed method achieves an average accuracy of 86.8%, which is approximately 13.7% higher than that of the traditional D-S method, demonstrating more substantial alignment with expert consensus and enhanced predictive capability. In terms of conflict management, the proposed method achieves a significant reduction in the average conflict degree (K ≈ 0.055), effectively mitigating the information distortion that commonly arises in multi-source expert evaluations. While Yager’s rule achieves zero conflict by shifting uncertainty to the frame of discernment, it sacrifices clarity and interpretability, which limits its practical applicability in design decision-making contexts. Furthermore, stability analysis under perturbation conditions reveals that the proposed method exhibits the lowest output variance (S ≈ 0.042), affirming its robustness against scoring noise and inter-expert subjectivity. Compared to traditional approaches, which either overfit or underweight inconsistent data, the average evidence-distance weighting strategy employed in this model achieves a more balanced and reliable fusion outcome.

In conclusion, the experimental results confirm that the proposed BP–D-S fusion model not only enhances the objectivity and consistency of emotional product evaluations but also exhibits superior adaptability in uncertain, multi-source decision environments. These advantages validate the model’s practical utility and theoretical significance in the field of user-centered product design assessment.

Discussion and outlook

Theoretical contributions and methodological expansion

The “BP neural network fusion with improved D-S evidence theory” product evaluation system proposed in this study offers a structured and adaptable theoretical model for integrating subjective evaluation into product design. In terms of theoretical construction, this paper gets rid of the dependence of traditional methods on experts’ experience, and realizes nonlinear learning from data input to subjective judgment by taking users’ and products’ features as inputs, and taking experts’ evaluation results as training targets, and training an emotion cognition model through BP neural network. This modeling approach, based on cognitive computing, provides new possibilities for perceptual design research, builds a bridge from the understanding of user needs to design optimization recommendations, and provides methodological support for the conversion of “qualitative to quantitative-quantitative modeling” in perceptual engineering.

Compared with traditional approaches, the theoretical innovations of this study are primarily manifested in the following three aspects: Firstly, by employing a data-driven backpropagation (BP) neural network, heterogeneous user and product features are mapped into probabilistic initial evidence (BPA), thereby effectively mitigating the subjectivity and static limitations inherent in expert-assigned values. To this end, we redesigned the input–output structure of the BP network to enable it to learn the nonlinear mapping of user characteristics and product elements onto expert sentiment judgements. Second, we propose a dynamic weighting mechanism based on average evidence distance. During fusion, this mechanism adjusts the basic probability allocation function by incorporating expert score divergence, thereby reducing distortion risks in high-conflict multi-source scenarios and enhancing result robustness and interpretability. Thirdly, we established an extensible ‘triadic collaborative evaluation’ paradigm, creating a closed-loop mechanism from perceptual evaluation to design element identification. This outputs ‘design elements requiring optimisation and their priority levels’, achieving a logical closed loop from sentiment perception to design feedback (see Table 14).

It should be noted that although BP neural networks and the enhanced D-S evidence fusion method have been applied in fields such as mechanical diagnostics and multi-source classification, their introduction into the domain of product sentiment evaluation still demonstrates significant theoretical innovation and methodological extension value. This study pioneers the integration of the BP–D-S fusion strategy with the triadic interaction relationship of ‘user–product–expert’ in product design. It introduces multiple enhancements in structural modelling and fusion mechanisms, offering novel insights for constructing a scientific, dynamic, and adaptive product sentiment evaluation system.

System scalability and potential for cross-domain applications

The evaluation model constructed in this study focuses on the fusion modeling of users’ subjective cognition and experts’ emotional judgment, and enables the analysis of emotional perception for complex product design elements through nonlinear mapping and a multi-source conflict processing mechanism. The model has demonstrated strong structural stability and data adaptability during the validation process, and its evaluation can be applied not only to furniture products but also has good potential for migration and cross-domain applications.

In the product category dimension, the model can be applied to a wide range of user experience-oriented consumer or service product scenarios, such as home appliances, transportation, recreational aids, and interactive interfaces. The evaluation process can be migrated to new domains by simply extending or replacing the input product feature parameters. For example, the model can realize the emotional evaluation modeling of smart devices or mobile terminals by introducing features such as “interface color”, “interaction smoothness”, “tactile feedback”, etc. The system has good multimodal scalability in terms of data sources and perceptual dimensions. Moreover, the system exhibits good multimodal scalability in terms of data sources and perception dimensions. The current model is primarily based on user rating data and expert subjective scoring. In the future, we can introduce user behavioral data (e.g., click rate, dwell time), physiological signals (e.g., facial expression, eye movement, heart rate) and other perceptual data channels, and further enhance the BP neural network’s ability to capture the implied emotional feedback through feature fusion strategies, to enhance the model’s predictive and discriminative abilities in the real use scenarios. In terms of evaluation goals and decision types, the model is not limited to emotional tendency judgment, but can also be adapted to complex attribute evaluation and multi-objective optimization tasks. In the actual design process, the model can be utilized in product concept selection, design plan screening, user group preference modeling, experience diagnosis, and other aspects, forming a closed loop of evaluation from preliminary research to post-feedback, thereby supporting agile iterative design practice.

Thanks to the controllable structure of the D-S evidence fusion module, the model is portable in handling multi-expert evaluation opinions, integrating conflicting viewpoints, and automatically adjusting weights. Regardless of the experimental scenario, whether it is a research experiment, design evaluation, or small-batch user testing, the model can be adapted and migrated to different user types and design tasks by adjusting the input weights or replacing the knowledge source module. The emotion evaluation system constructed in this study is not only limited to the application validation of current furniture products, but also has high model generalization and scalability. By adjusting the input structure, expanding the data dimensions, and reconstructing the evaluation objectives, the model is expected to be developed into an intelligent user experience modeling tool that supports multi-domain, multi-task, and multi-source data fusion. This tool can provide methodological support for product optimization, design decision-making, and human-oriented innovation.

On the hardware implementation potential of emotional decision-making frameworks

With the advancement of neuromorphic computing and edge computing, the proposed affective evaluation framework demonstrates viable implementation potential at the hardware level. Overall, the framework comprises two components: firstly, a BP neural network for affective mapping; secondly, an enhanced D-S evidence theory for multi-source evidence fusion. The former can be mapped onto neuromorphic chips or memristor arrays, leveraging their high parallelism and energy efficiency in matrix–vector operations to accelerate the nonlinear mapping between user characteristics and emotional responses. The latter can be implemented via FPGAs, embedded systems, or dedicated logic circuits to perform computational tasks such as probability distribution, conflict detection, and weighted fusion. Existing research36 provides a reference pathway for the hardware implementation of this framework. At the implementation level, the BP network component may first undergo training and optimisation on the server side, with the quantised or pruned lightweight model subsequently deployed onto NPUs, FPGAs, or resistive memory arrays to reduce inference energy consumption and latency. The D-S fusion module can efficiently compute evidence conflict scores and weighted synthesis using parallelised logic units, while enhancing numerical stability through fixed-point and normalisation design. It should be noted that while analog implementations, such as resistive memory, offer exceptional energy efficiency, they are constrained by device non-idealities (e.g., noise and drift), necessitating supplementary calibration and fault-tolerance mechanisms. In contrast, digital implementations like FPGAs or NPUs demonstrate greater engineering feasibility and reliability, making them preferable for prioritised deployment in practical systems.

In summary, the affective decision-making framework developed in this study demonstrates strong potential for hardware portability. By accelerating BP network inference through neuromorphic chips and integrating enhanced D-S fusion via FPGAs or embedded circuits, an optimal balance between real-time performance and energy efficiency can be achieved. This provides a viable technical pathway for deploying the model in real-time embedded scenarios such as smart home appliances and interactive terminals, while also laying the groundwork for future development of integrated hardware-software affective evaluation systems.

Research limitations and future perspectives

Although the sentiment evaluation model proposed in this study, which combines a BP neural network with an enhanced D-S evidential theory, demonstrated robust stability and effectiveness in experiments, several limitations remain. These limitations also point to directions for future research. Firstly, the samples utilised in this study exhibit constraints in both scale and distribution. The current training data originates from specific channels, with relatively limited user and expert samples. Furthermore, the distribution is concentrated across dimensions such as geography and cultural background. This may constrain the model’s generalisation capability when confronted with broader user groups and product styles. Secondly, the effectiveness of model fusion is constrained by the subjectivity inherent in expert ratings. Although this study mitigates subjective bias to some extent through conflict-weighted strategies, the robustness of information fusion remains at risk of decline in high-conflict scenarios where expert opinions diverge significantly. Precisely quantifying and calibrating expert trust levels is crucial for enhancing the reliability of models. Thirdly, this study constructs models based on static data, which fail to capture and adapt to dynamic changes over time effectively. Current static models lack mechanisms to perceive and respond to long-term shifts in preference triggered by market trends, societal events, or users’ personal experiences. This limitation restricts their application in long-term product iteration and lifecycle management. Concurrently, the proposed model provides a natural foundation for integration with cutting-edge AI paradigms to address the limitations of their current static modelling approaches. Specifically, the challenge of handling dynamic, multi-source user feedback can be tackled by incorporating architectures such as adaptive segmentation37, which is specifically designed for robust analysis of irregularly sampled multivariate time series. This will enable our model to process asynchronous data streams from reviews and social media efficiently.

Furthermore, to realise the envisioned ‘design-evaluate-redesign’ closed loop, a hierarchical reinforcement learning approach based on state relays may be employed38. This approach formalises the design process as a hierarchical game, wherein a meta-controller manages high-level design strategies based on sentiment evaluation states, while directing sub-controllers to execute specific design modifications. This creates a genuinely adaptive and self-improving product development system. Through the exploration of the aforementioned pathways, the affective evaluation framework proposed in this study holds promise for achieving greater universality, robustness, and cross-domain applicability in the future.

Data availability

All data is included in the main text.

References

Wang, Y., Ma, H. S., Yang, J. H. & Wang, K. S. Industry 4.0: A way from mass customization to mass personalization production. Adv. Manuf. 5(4), 311–320 (2017).

Carayannis, E. & Coleman, J. Creative system design methodologies: The case of complex technical systems. Technovation 25(8), 831–840 (2005).

Bénabès, J., Poirson, E., Bennis, F., & Ravaut, Y. (2011, August). Modular optimization strategy for layout problems. In 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 2011).

Saaty, T. L., Peniwati, K. & Shang, J. S. The analytic hierarchy process and human resource allocation: Half the story. Math. Comput. Model. 46(7–8), 1041–1053 (2007).

Poria, S., Cambria, E., Hussain, A. & Huang, G. B. Towards an intelligent framework for multimodal affective data analysis. Neural Netw. 63, 104–116 (2015).

Liang, R. Y. et al. The research on the application of kansei engineering in the product design. Adv. Mater. Res. 690, 3453–3456 (2013).

Hassenzahl, M., Diefenbach, S. & Göritz, A. Needs, affect, and interactive products–Facets of user experience. Interact. Comput. 22(5), 353–362 (2010).

Jin, J., Jia, D. & Chen, K. Mining online reviews with a Kansei-integrated Kano model for innovative product design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 60(22), 6708–6727 (2022).

Li, X., Su, J., Zhang, Z. & Bai, R. Product innovation concept generation based on deep learning and Kansei engineering. J. Eng. Des. 32(10), 559–589 (2021).

Zhu, G. N., Hu, J. & Ren, H. A fuzzy rough number-based AHP-TOPSIS for design concept evaluation under uncertain environments. Appl. Soft Comput. 91, 106228 (2020).

Zuo, Y. & Wang, Z. Subjective product evaluation system based on Kansei Engineering and analytic hierarchy process. Symmetry 12(8), 1340 (2020).

Van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. & Dorst, K. Advancing the strategic impact of human-centred design. Des. Stud. 53, 1–23 (2017).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323(6088), 533–536 (1986).

Guliyev, N. J. & Ismailov, V. E. Approximation capability of two hidden layer feedforward neural networks with fixed weights. Neurocomputing 316, 262–269 (2018).

Maiorov, V. & Pinkus, A. Lower bounds for approximation by MLP neural networks. Neurocomputing 25(1–3), 81–91 (1999).

Yao, J., Goswami, M., & Chen, C. Neural Network Expressive Power Analysis Via Manifold Topology.

Ito, Y. Approximation of functions on a compact set by finite sums of a sigmoid function without scaling. Neural Netw. 4(6), 817–826 (1991).

Han, W. et al. Research on the prediction method of centrifugal pump performance based on a double hidden layer BP neural network. Energies 12(14), 2709 (2019).

Su, X., Jiang, X. H., Zhang, S. M., & He, Y. (2018). Application of Double-Hidden Layer BP Neural Network in Transformer Fault Alarm. In Advances in Smart Vehicular Technology, Transportation, Communication and Applications: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Smart Vehicular Technology, Transportation, Communication and Applications, November 6–8, 2017, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 1 (pp. 161–169). Springer International Publishing.

Fei, R., Guo, Y., Li, J., Hu, B. & Yang, L. An improved BPNN method based on probability density for indoor location. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 106(5), 773–785 (2023).

Zhang, T., Chen, L. & Wang, J. Multi-objective optimization of elliptical tube fin heat exchangers based on neural networks and genetic algorithm. Energy 269, 126729 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Improved faster R-CNN for fabric defect detection based on Gabor filter with Genetic Algorithm optimization. Comput. Ind. 134, 103551 (2022).

Wang, Q., Li, S., Li, R. & Jiang, F. Underestimated impact of the COVID-19 on carbon emission reduction in developing countries–a novel assessment based on scenario analysis. Environ. Res. 204, 111990 (2022).

Yi, X., Wang, Z., Liu, S., Hou, X. & Tang, Q. An accelerated degradation durability evaluation model for the turbine impeller of a turbine based on a genetic algorithms back-propagation neural network. Appl. Sci. 12(18), 9302 (2022).

Man, D. I. N. G., Tingting, D. I. N. G., Meijia, S. O. N. G., Xinxin, Z. H. A. N. G. & Zhen, L. I. U. Product color emotional design method based on implicit measurement and BP neural network. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 29(2), 616 (2023).

Xu, H., Ren, R. & Chen, H. Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks. AUTEX Res. J. 24(1), 20230007 (2023).

Cai, W., Wang, Z., Wang, Y. & Zhou, M. Research on wheelchair form design based on Kansei engineering and GWO-BP neural network. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 10258 (2025).

Liang, D. Aesthetic value evaluation for digital cultural and creative products with artificial intelligence. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022(1), 8318620 (2022).

Zou, M. et al. Identification of the shear parameters for lunar regolith based on a GA-BP neural network. J. Terrramech. 89, 21–29 (2020).

Xiao, R. et al. The Prediction of liquid holdup in horizontal pipe with BP neural network. Energy Sci. Eng. 8(6), 2159–2168 (2020).

Yager, R. R. On the Dempster-Shafer framework and new combination rules. Inf. Sci. 41(2), 93–137 (1987).

Feng, S., Tang, L., Huang, M. & Wu, Y. Integrating D-S evidence theory and multiple deep learning frameworks for time series prediction of air quality. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 5971 (2025).

Yang, A. et al. Decision fusion scheme based on mode decomposition and evidence theory for fault diagnosis of drilling process. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 20(2), 2017–2028 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Inconsistency elimination of multi-source information fusion in smart home using the Dempster-Shafer evidence theory. Inf. Process. Manage. 61(4), 103723 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Guo, Y. & Song, Z. Dynamic curve fitting and bp neural network with feature extraction for mobile specific emitter identification. IEEE Access 9, 33897–33910 (2021).

Sun, J., Gao, P., Liu, P. & Wang, Y. Memristor-Based feature recall neural network circuit with temporal differentiation of emotion and its application in parts inspection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2025.3556069 (2025).

Zhu, E., Wang, S., Liu, C. & Wang, J. Adaptive tokenization transformer: Enhancing irregularly sampled multivariate time series analysis. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2025.3554249 (2025).

Liu, C. et al. Boosting reinforcement learning via hierarchical game playing with state relay. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 36(4), 7077–7089 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kun Wang: Conceptualization Kexiang Li: Writing—original draft Xueqian Jiang: Formal analysis Chaomian Chen: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All research methods strictly adhere to relevant guidelines and regulations. This research protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Quanzhou Normal University. All participants in this study have signed informed consent forms. For participants under the age of 18, informed consent has been obtained from their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Li, K., Jiang, X. et al. An emotion-oriented product evaluation model based on BP neural network and improved dempster–shafer theory. Sci Rep 15, 39324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23138-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23138-0