Abstract

In this Research Ethics Board-approved retrospective study, we evaluated pre-infusion [18F]FDG PET/CT prognostic value in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients undergoing chimeric antigen T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. A total of 159 Patients treated with CAR-T between 2018 and 2023 were reviewed. Deauville scores 4 and 5 were considered to be a significant residual disease at baseline. Standardized uptake values (SUVs), whole-body metabolic tumour volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) were calculated. Additionally, the furthest distance between tumoral lesions throughout the body (Dmax) and from the spleen (spleen Dmax) were measured. Survival analyses evaluated the predictive value of the clinical and imaging-derived variables for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) prognostication. Of 129 DLBCL patients with pre-infusion [18F]FDG PET/CT, 117/129 (91%) had significant residual disease. The median PFS and OS post-CAR-T were six and nine months, respectively. For PFS, variables that remained significant in the multivariate analysis were serum LDH (HR = 1.68) and TLG (HR = 4.31), being independent predictors of PFS. Considering OS, the only variable which retained its significance in the multivariate analysis was [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived standardized Dmax (HR = 3.28). Pre-infusion [18F]FDG PET/CT can provide valuable prognostic information in CAR-T candidates, enhancing patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of lymphoid cancer, comprising nearly one-third of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients1,2. First-line standard-of-care treatment for DLBCL typically involves chemo-immunotherapy, most commonly the R-CHOP regimen3. However, alternative regimens such as pola-R-CHP for the activated B-cell subtype and DA-EPOCH-R for double-hit lymphomas are partly used based on molecular and clinical risk stratification. Although effective, depending on the initial stage, nearly half of the patients show relapse and have to either undergo new systemic chemotherapy or autologous stem cell transplantation. Furthermore, overall survival (OS) in relapsed/refractory DLBCL can be limited to as low as six months4. Thus, to improve patient outcomes, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy was recently approved to treat DLBCL patients after two or more failed lines of systemic therapy, achieving durable responses in up to 30–40% of relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients2.

Meanwhile, [18F]FDG PET/CT is an established, highly informative/prognostic imaging method for evaluating lymphoma patients. It is the current standard of care for staging and follow-up in a broad range of haemato-oncological clinical scenarios5,6. [18F]FDG PET/CT utility spans from primary staging and follow-up, supporting the determination of appropriate treatment intensity in cases of early relapse and also showing encouraging results regarding prognostication7. In the context of CAR-T therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, there are only a few studies available evaluating [18F]FDG PET/CT as a modality to predict treatment success and probability of possible adverse events, such as cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome4,7,8,9. In terms of patient survival, it was shown that [18F]FDG avidity at the time of decision was independently correlated with OS 4. Moreover, metabolic tumour volume (MTV) was inversely correlated to a complete metabolic response at 1-month follow-up post-therapy, increasing the chance of relapse after treatment7. Additionally, total lesion glycolysis (TLG), MTV, and average standardized uptake value (SUVmean) could predict OS and progression-free survival (PFS)8.

Thus, although the current literature is limited, [18F]FDG PET/CT was shown to be potentially beneficial for CAR-T therapy success prognostication in preliminary investigations. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of pre-treatment [18F]FDG PET/CT in relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients undergoing CAR-T. We focused on relapsed/refractory patients with significant residual disease to investigate the added value of [18F]FDG PET/CT in this high-risk patient population.

Methods

Patient population and studied parameters

In this retrospective study, we reviewed 159 patients referred to our department to undergo imaging prior to receiving CAR-T therapy between January 2018 and May 2023. This study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and institutional guidelines. All methods and protocols were approved by the ethics committee at the University Health Network, University of Toronto. Considering the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived by the institutional review board and ethics committee at the University Health Network.

The inclusion criteria were patients with baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT prior to CAR-T infusion (after T-cell harvesting) who had histopathology-proven diagnosis of DLBCL. All patients had relapsed/refractory DLBCL, meaning they experienced at least treatment failure with two lines of standard therapies. Finally, 129 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and entered the current study. Figure 1 shows the patient selection flowchart. Demographic information (e.g., age, sex, race), clinical data (e.g., serum LDH level, Lugano stage, ECOG score, previous treatments, history of treatment failures), histopathology details and prognostic endpoints (e.g., disease progression, death) of all patients were gathered. Additionally, the International Prognostic Index (IPI), its NCCN version (NCCN-IPI) and the more recently introduced International Metabolic Prognostic Index (IMPI, including age, stage and MTV) were determined for all patients at the time of CAR-T administration10.

[18F]FDG PET/CT imaging protocol

[18F]FDG PET/CT imaging was conducted based on our centre’s standardized institutional protocol. Imaging was performed in 3D mode with a dedicated in-line PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biograph mCT 40 and Siemens Vision, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Patients were instructed to keep at least 6 h fasting before the radiopharmaceutical administration. [18F]FDG, 5 MBq/Kg of body weight, was then injected intravenously. After approximately 60 min, a spiral CT imaging was performed to cover the skull base to the upper thighs (whole-body imaging) unless there was a documented/suspicious involvement of the lower limbs. The scan was performed with the following parameters: 120 kV peak, 40–105 mAs, 3.0 mm slice width, 2.0 mm collimation, an overlap of 2.0 mm, 0.8 s rotation time and 8.4 mm feed/rotation. Following CT, PET images were acquired (for a duration of 2–3 min/bed position in Biograph and 1–1.5 mm/sec bed speed in Vision). A PET scan using data correction (e.g., scatter and decay) was obtained, covering the identical transverse field of view of the CT acquisition. The PET image dimensions were a pixel size of 2.6 × 2.6 mm and a slice thickness of 3.27 mm, filtered with a Gaussian filter (4 mm and 2 mm full width at half maximum in Biograph and Vision, respectively).

[18F]FDG PET/CT interpretation and image analysis

[18F]FDG PET/CT scans were interpreted by two expert physicians in consensus using a standard imaging workstation (Mirada XD Workstation, Mirada Medical). On [18F]FDG PET/CT images, all metabolically active tumoral lesions were identified and located throughout the body. Deauville scores were assigned based on the relative uptake of the hottest tumoral lesion compared to the mediastinal and hepatic backgrounds. Deauville scores 4 and 5 were considered a significant residual disease at baseline and non-complete response in follow-up. From each scan and from all lesions, SUVmax, SUVmean, SUVpeak (1-mm spherical VOI), whole-body MTV and whole-body TLG were calculated. MTV was calculated with 41% SUVmax thresholding11. All these parameters were extracted using a 3D method of segmentation via commercially available software (LIFEx, v.7, Inserm, France)12. Also, hepatic average uptake was considered to calculate tumour-to-background ratios by drawing a 3 cm3 VOI on the uninvolved right hepatic lobe. For evaluation of the distance of tumoral involvement, the furthest distance between tumoral lesions throughout the body (Dmax) and their maximum distance from the spleen (Spleen Dmax) were calculated. These distances were also normalized based on body surface area (\(\:\sqrt{(weight\:x\:height/3600}\)) to generate standardized Dmax and standardized Spleen Dmax13,14.

Patient follow-up

All patients were followed up by inpatient/outpatient visits until October 31, 2023. The date and location of the disease progression were documented. Also, in case of patient death, the date was documented. Time to progression/death was calculated from the CAR-T administration to the documented progression/death or the final follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical parameters were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and frequency (%), respectively. The differences in the clinical and [18F]FDG PET/CT parameters between non-complete and complete response groups were evaluated using the Chi-square test and student t-test for the categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Regarding prognostic evaluation, the continuous variables were converted into dichotomized variables using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and taking the coordinate point with the highest Youden index as the cut-off. For PFS and OS prognostication, univariate analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. PFS was defined as the time from CAR-T infusion until relapse, progression, death, or the last follow-up date. OS was defined as the time from CAR-T infusion until patient death or the last follow-up date. The significance of the difference was investigated using the univariate Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Significant parameters in the univariate analysis entered the multiple Cox regression and were presented with their hazard ratio (HR) along a 95% confidence interval (95%CI). All dichotomized versions of the variables showed better prognostication value compared to their continuous counterparts. Thus, only dichotomized variables were considered to enter multivariate analysis. Moreover, to address high collinearity among PET-derived variables, we performed groupwise pre-selection based on univariate prognostic strength. In this regard, among the three main groups of [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived variables (“SUVs”, “MTV/TLG”, and “Distances”), we selected parameters with the highest prognostication (based on stepwise variable selection). For example, TLG was selected over MTV for PFS due to its higher hazard ratio and prognostic value in univariate analysis. Notably, no missing data was present in the database to need treatment. However, considering patients’ response status at 1-month and 3-month time points after CAR-T (complete vs. non-complete response), these two parameters were not entered into the multivariate analysis because they were not a baseline parameter and also would limit the patient population (to 51 and 66 patients with 1-month and 3-month scans, respectively). All data were analyzed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29, IBM Corp., NY, USA). The statistical significance level was set at a two-sided p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Overall, 129 patients (mean age = 59 years) with pathology-proven DLBCL who underwent pre-CAR-T baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT entered the study. The patient selection flowchart is provided in Fig.1. Detailed characteristics of the study population can be found in Table 1.

Baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT findings

Patients underwent baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT with a mean interval of 12 (± 6; median = 12) days prior to CAR-T infusion. Among the scans, 117/129 (91%) were positive for an [18F]FDG-avid significant residual disease, having Deauville scores of 4 (30/117; 26%) and 5 (87/117; 74%). Table S1 shows [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived measurements of these positive scans (n = 117). Overall, 62/117 (53%) of the patients had extranodal lymphoma manifestations, the most common being bone/bone marrow involvement (29/117; 25%), followed by hepatic (12/117; 10%), muscular (12/117; 10%), and pulmonary (10/117; 9%) lymphomatous involvements.

Early post-treatment follow-up

Among 117 [18F]FDG PET-positive patients at the time of baseline assessment, 51 (44%) and 66 (56%) had 1-month and 3-month post-CAR-T [18F]FDG PET/CT, respectively. The mean intervals from the CAR-T infusion date were 33 (± 8; median = 31) and 89 (± 9; median = 90) days, respectively. The changes of disease burden between the baseline and 1-month [18F]FDG PET/CTs are shown in Fig. 2 (for those 51 patients with 1-month [18F]FDG PET/CT). The changes of disease burden between the baseline, 1-month, and 3-month [18F]FDG PET/CTs are shown in Figure S1 (for those 28 patients who completed all three scans).

Clinical and [18F]FDG PET/CT parameters of the 51/117 patients who had a 1-month [18F]FDG PET/CT were evaluated. Among them, 14/51 (27%) experienced a complete response, while 37/51 (73%) still had Deauville scores of 4 and 5 at one month. Table S2 shows the comparison details. MTV, Dmax and standardized Dmax at baseline were significantly lower in patients who experienced a non-complete response at 1-month (1-month timepoint-specific response and not the overall response). Table S3 shows similar data regarding the differences between complete and non-complete responses at 3-month post-therapy for 66/117 patients. Among them, 36/66 (55%) and 30/66 (45%) patients had complete and non-complete responses, respectively. Contrary to the 1-month-specific status, no difference was detected in baseline scan parameters between patients who experienced complete response three months after CAR-T infusion versus those who did not. Noteworthy, among those 12 aforementioned cases who had negative baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT, five had 1-month, and five had 3-month scans. At both time points, 4/5 cases showed sustained complete response.

Patient survival

In terms of patient survival, the relationships between baseline clinical and [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived factors with PFS and OS were evaluated. The median PFS and OS were 181 and 277 days after CAR-T, respectively. Overall, 49/117 (42%) patients experienced disease progression post-CAR-T therapy with a median of 86 days. Additionally, 35/117 (30%) deaths were documented during follow-up, with a median of 173 days.

Details of the findings in regard to PFS and OS can be found in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Notably, while the 1-month scan status (timepoint-specific complete vs. non-complete response) had no significant prognostication value considering PFS and OS, the 3-month scan response interpretation showed to be of value in both.

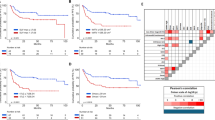

For PFS, variables which remained significant in the multivariate analysis (Table 2) were LDH (HR = 1.68; 95%CI: 1.00–2.82.00.82) and TLG (HR = 4.31; 95%CI: 1.00–18.52.00.52), being independent predictors of PFS. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for these independent prognostic factors. Considering OS, the only variable which retained its significance in the multivariate analysis (Table 3) was [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived standardized Dmax (HR = 3.28; 95%CI: 1.16–9.34), being an independent predictor of OS. The Kaplan-Meier curve for standardized Dmax can be found in Fig. 4.

As sub-groups, we also analyzed the prognostic value of the significant parameters in two groups with particular CAR-T products, Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (axi-cel) and Tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel). Regarding PFS in axi-cel group, LDH (HR = 2.05; 95%CI: 1.12–3.74; p = 0.019) and TLG (HR = 21.04; 95%CI: 2.89–152.94.89.94; p = 0.003) retained their statistical significance. However, in the limited population receiving tisa-cel, both LDH (HR = 2.08; 95%CI: 0.74–5.84; p = 0.166) and TLG (HR = 1.16; 95%CI: 0.26–5.15; p = 0.848) lost their statistical significance. Considering OS, standardized Dmax remained significant for the axi-cel subgroup (HR = 7.56; 95%CI: 2.26–25.31; p = 0.001), however, it lost its statistical significance for the tisa-cel subgroup (HR = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.23–6.18; p = 0.835).

Discussion

We studied DLBCL patients who underwent [18F]FDG PET/CT for pre-treatment assessment prior to CAR-T infusion. Among patients who had significant residual disease in the baseline scan and underwent the follow-up [18F]FDG PET/CT, over one-fourth experienced complete metabolic response to therapy at 1-month post-CAR-T. Our results showed that baseline MTV and Dmax (with/without normalization) significantly differed between response groups. However, reviewing the 3-month PET-based response, no significant prognostic parameter was identified. Noteworthy, the majority of patients who had Deauville scores of 1–3 in the baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT, showed to be in complete remission at the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups.

Regarding patient survival, our study population’s PFS and OS calculated durations (median) were approximately six and nine months, respectively. Less than half of the patients experienced disease progression during our follow-up, and less than one-third were deceased. In the multivariate analysis for PFS prediction, LDH and TLG at baseline scan showed significant prognostic values, being independent predictors of PFS. In the OS multivariate analysis, only standardized Dmax retained its significance. These results can underscore the most prominent independent factors for CAR-T prognostication, which have the potential to be considered in [18F]FDG PET/CT interpretation and clinical reports.

There are only very few studies available in the current literature to compare our results with. The value of MTV in non-refractory DLBCL prognostication has been documented in the literature15,16,17. It has been reported that whole-body/total MTV was an even better prognosticator of PFS and OS than clinical parameters such as LDH level, as well as indices like IPI and NCCN-IPI13,18. Few studies evaluated the prognostic value in the CAR-T therapy context19. Cohen et al. reported that high MTV at baseline could predict shorter OS 4. However, for PFS, it did not reach statistical significance in their small population of 48 patients. In another study, Dean et al. reported that high baseline MTV was associated with both worse PFS and OS in DLBCL patients receiving CAR-T therapy (n = 96)20, in line with our findings. Marchal et al. also recently showed that MTV was a significant predictor of PFS and OS after CAR-T therapy21. Also noteworthy is a study by Sesques et al., in which the authors evaluated MTV at various cut-offs and only found a statistically significant association with patient survival (PFS and OS) at one of the four cut-offs11. This signifies the importance of defining low versus high MTV values.

Furthermore, Dean et al. reported that patients with lower MTV were more likely to experience a complete response to treatment20. Notably, they assessed response to treatment at the last follow-up. In our study, patients who experienced a complete response at 1-month post-treatment had higher baseline MTV (and Dmax) compared to patients with a non-complete response. However, later at 3-month post-treatment, this difference lost its statistical significance in our cohort, meaning baseline MTV was not different between patients who achieved a complete response versus those who did not at 3-month post-treatment. Our results also showed that higher baseline MTV was a significant predictor of worse PFS. These findings at sequential timepoints following CAR-T therapy may indicate the limitations of early PET timing (e.g., 1-month PET), where inflammation and tumour lysis may influence response criteria, i.e., demonstrating pseudo-progression.

Our findings at three months post-therapy, however, showed that [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived parameters were not significantly different. Thus, it seems the timepoint of response assessment (at least in early assessment) is critical and can affect the predictors’ value significantly since parameters may vary during follow-up in such complex diseases. Also, localized resistant lymphoma manifestation (i.e. cases with limited residual disease meaning low volume MTV and short Dmax) may not respond to therapy quickly (at one month), and it takes time to reach the expected outcome for CAR-T therapy. Thus, regular [18F]FDG PET/CT imaging follow-up could therefore be justified in this patient population, based on clinical symptoms6. Our results also showed that patient response at 3-month scan was more associated with PFS and OS than the 1-month scan. It is worth noting that several patients with Deauville score 4 at baseline remained stable or showed some degree of disease progression at 1-month, raising the possibility of pseudo-progression, a phenomenon occasionally observed with immunotherapies, including CAR-T. This may reflect inflammatory responses rather than true disease persistence, necessitating further investigation into this topic and possibly cautious interpretation of early [18F]FDG PET/CT findings. Our results are partly supported by the recent prospective study done by Farolfi et al., investigating the value of both 1-month and 3-month post-treatment [18F]FDG PET/CT22. In their single-centre study of 61 patients treated with CAR-T therapy, semiquantitative [18F]FDG PET/CT-derived parameters (SUVmax, MTV, and TLG) at both 1 month and 3 months post-infusion were significantly associated with OS and PFS. However, their multivariable analysis identified 3-month post-CAR-T [18F]FDG PET/CT as a stronger prognosticator (SUVmax on 3-month [18F]FDG PET/CT in particular), being more robust than the 1-month assessment and outperforming clinical factors such as serum LDH and age.

Regarding serum LDH level, our findings supported previous findings of Cohen et al., who found it to be significant in the post-CAR-T therapy OS prognostication4. Similarly, Dean et al. reported that LDH level was associated with PFS and OS, though it was significant only in one of their two study cohorts20. Dmax (with/without normalization) was also previously proposed as a strong predictor of survival in DLBCL patients, which could combine with other metabolic parameters (e.g., MTV) to be a more robust prognosticator13,23,24. However, we found only one study in this regard in the context of CAR-T therapy, in which standardized Dmax was evaluated21. Marchal et al. evaluated various baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT parameters and reported that standardized Dmax was an independent prognosticator for OS, similar to our findings. Also similar to us, standardized Dmax, although significant, could not retain its significance in their multivariate analysis for PFS prediction. As an advantage, we included four different metrics to measure the distance of tumoral involvement (Dmax and spleen Dmax, both with/without body surface area normalization) and showed that standardized Dmax could significantly stand out over parameters in terms of post-CAR-T therapy prognostication. To our knowledge, there is no similar experience in the literature, making our results novel in this regard and requiring future studies for confirmation.

Another finding in the study of Marchal et al. was that SUVmax was a significant parameter for PFS but not OS 20, similar to our findings. However, in the aforementioned study by Cohen et al., high SUVmax was strongly associated with both shorter PFS and OS 4. Although the value of lesion uptake was shown to be debatable to some extent, we made a robust comparison of different uptake calculations. Thus, based on our results, it seems SUVmax-to-Liver background is a stronger predictor of patient survival (PFS and OS) compared to SUVs (e.g., SUVmax), and future studies should consider taking this ratio into account for their prognostic evaluations. Lastly, we noticed that Cohen et al. was the only study in which TLG was evaluated for CAR-T therapy prognostication. In their study of 48 patients, TLG at baseline could predict OS but not PFS, contrary to our results that showed significant prognostication for both outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. The major one was the number of patients, which could potentially affect our findings. However, we tried to make our study population more homogenous for survival analyses by limiting the patients to DLBCL patients who had significant residual disease (Deauville scores of 4–5) at the time of baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT. The other major limitation of our study was regarding patient follow-up. We could not follow all patients until disease progression/death documentation, and this could have an impact on our survival analyses. Also, some patients underwent earlier reassessment after CAR-T administration (one month), while some others underwent later response assessment (three months). This might result in different timings for disease progression detection in some patients, and consequently, affect the calculation of the PFS intervals by introducing a potential bias in longitudinal assessment. Third, measuring different parameters on [18F]FDG PET/CT images may be operator-dependent to some extent. However, we used well-established, dedicated software for this purpose. Also, all processes were done by expert physicians to minimize the possible errors as much as possible. Fourth, as mentioned, although we utilized a robust analysis to reach the optimal cut-off, the defined cut-offs for the studied parameters could still be dependent on our population characteristics, which may make them subject to change in future studies. Lastly, our patients received different CAR-T products, which potentially could result in different responses to treatment, and consequently, different survival rates. Although we could not investigate the differences precisely due to the limited size of the subgroups, we could show that at least in the main subgroup with the axi-cel product, the prognostic parameters remained statistically significant for both PFS and OS prognostication.

In conclusion, pre-infusion [18F]FDG PET/CT can provide valuable prognostic information concerning response to treatment and survival in DLBCL patients receiving CAR-T therapy. The most significant predictors of patient outcomes would be serum LDH level, extranodal lymphomatous involvement, SUVmax-to-background, MTV, TLG and standardized Dmax. These parameters, as well as the proposed cut-offs, could be further evaluated in prospective studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

28 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36849-9

References

Teras, L. R. et al. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by world health organization subtypes. Cancer J. Clin. 66, 443–459 (2016).

Susanibar-Adaniya, S. & Barta, S. K. Update on diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a review of current data and potential applications on risk stratification and management.. Am. J. Hematol. 96, 617–629 (2021).

Visco, C. et al. Efficacy of R-COMP in comparison to R-CHOP in patients with DLBCL: A systematic review and single-arm metanalysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 163, 103377 (2021).

Cohen, D. et al. [(18)F]FDG PET-CT in patients with DLBCL treated with CAR-T cell therapy: a practical approach of reporting pre- and post-treatment studies. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 49, 953–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-021-05551-5 (2022).

Milgrom, S. A., Rechner, L. & Berthelsen, A. The optimal use of PET/CT in the management of lymphoma patients. Br. J. Radiol. 94, 20210470. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20210470 (2021).

Murad, V., Kohan, A., Ortega, C., Prica, A. & Veit-Haibach, P. Role of FDG PET/CT in Patients With Lymphoma Treated With CAR T-Cell Therapy: Current Concepts. American J. Roentgenology 222(2), e2330301 (2023).

Georgi, T. W. et al. Prognostic value of baseline and early response FDG-PET/CT in patients with refractory and relapsed aggressive B-cell lymphoma undergoing CAR-T cell therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04587-4 (2023).

Hong, R. et al. Tumor burden measured by 18F-FDG PET/CT in predicting efficacy and adverse effects of chimeric antigen receptor T-Cell therapy in Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 713577. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.713577 (2021).

Vercellino, L. et al. Current and future role of medical imaging in guiding the management of patients with relapsed and refractory Non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with CAR T-Cell therapy. Front. Oncol. 11, 664688. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.664688 (2021).

Mikhaeel, N. G. et al. Proposed new dynamic prognostic index for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: international metabolic prognostic index. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 2352 (2022).

Sesques, P. et al. Prognostic impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma treated with anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin. Nucl. Med. 46, 627–634 (2021).

Nioche, C. et al. LIFEx: a freeware for radiomic feature calculation in multimodality imaging to accelerate advances in the characterization of tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 78(16), 4786–6789 (2018).

Cottereau, A. S. et al. Risk stratification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using lesion dissemination and metabolic tumor burden calculated from baseline PET/CT. Ann. Oncol. 32, 404–411 (2021).

Girum, K. B. et al. Tumor location relative to the spleen is a prognostic factor in lymphoma patients: a demonstration from the REMARC trial. J. Nucl. Med. 65, 313–319 (2024).

Mikhaeel, N. G. et al. Combination of baseline metabolic tumour volume and early response on PET/CT improves progression-free survival prediction in DLBCL. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 43, 1209–1219 (2016).

Cottereau, A. S. et al. Molecular profile and FDG-PET/CT total metabolic tumor volume improve risk classification at diagnosis for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 3801–3809 (2016).

Kostakoglu, L. et al. Baseline PET-derived metabolic tumor volume metrics predict progression-free and overall survival in DLBCL after first-line treatment: results from the phase 3 GOYA study. Blood 130, 824 (2017).

Vercellino, L. et al. High total metabolic tumor volume at baseline predicts survival independent of response to therapy. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 135, 1396–1405 (2020).

Vercellino, L. et al. Current and future role of medical imaging in guiding the management of patients with relapsed and refractory non-hodgkin lymphoma treated with CAR T-Cell therapy. Front. Oncol. 11, 664688 (2021).

Dean, E. A. et al. High metabolic tumor volume is associated with decreased efficacy of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 4, 3268–3276 (2020).

Marchal, E. et al. Baseline [18F] FDG PET features are associated with survival and toxicity in patients treated with CAR T cells for large B cell lymphoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 51, 481–489 (2024).

Farolfi, A. et al. Semiquantitative PET parameters refine prognosis in CAR T–treated lymphoma after 1 and 3 months: a prospective single-center study. J. Nucl. Med. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.125.269670 (2025).

Cottereau, A. S. et al. 18F-FDG PET dissemination features in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are predictive of outcome. J. Nucl. Med. 61, 40–45 (2020).

Dang, J. et al. Predictive value of Dmax and% ∆SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET/CT for the prognosis of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Med. Imaging. 23, 173 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Patrick Veit-Haibach proposed the idea of the study and was responsible for conceptualizing and designing the investigation. Seyed Ali Mirshahvalad, Andres Kohan, and Roshini Kulanthaivelu performed the data gathering. Seyed Ali Mirshahvalad did the statistical analyses. Seyed Ali Mirshahvalad and Patrick Veit-Haibach were responsible for writing the first draft of the manuscript. All other co-authors (Andres Kohan, Roshini Kulanthaivelu, Claudia Ortega, Ur Metser, David Hodgson, Robert Kridel, Christine Chen, Sita Bhella) collaborated in the review and revision of the manuscript draft. Patrick Veit-Haibach was responsible for the supervision and project management. All authors read and accepted the final version prepared for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study received institutional review board and ethics committee approval.

Consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, obtaining written informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Methods, under the subheading ‘[18F]FDG PET/CT interpretation and image analysis’, where a reference was omitted. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirshahvalad, S.A., Kohan, A., Kulanthaivelu, R. et al. Added prognostic value of baseline pre-infusion 18F-FDG PET/CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Sci Rep 15, 39540 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23159-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23159-9