Abstract

To evaluate the feasibility of an AI system for identifying active tuberculosis (ATB) in TB-specialized hospitals in high-prevalence settings. An AI system designed to identify ATB was retrospectively validated using a multi-center dataset of 1741 CT images from three TB-specialized hospitals. The dataset included ATB, pneumonia, pulmonary nodules and normal cases. The system’s utility and generalizability were assessed across four application scenarios, and pairwise comparisons of the system’s performance were conducted among the three hospitals. The system demonstrated good generalizability across three settings. It achieved an AUC over 0.9 for distinguishing between abnormal and normal, over 0.95 for distinguishing between ATB and normal, over 0.8 for distinguishing between ATB and non-ATB, and an AUC ranging from 0.762 to 0.906 for distinguishing between ATB and other abnormalities (pneumonia and pulmonary nodules). For all evaluation matrices, at least one pairwise comparison showed no significant difference in performance among the three hospitals across different scenarios. Using an AI system to identify ATB in CT images is feasible in TB-specialized hospitals. This evaluation provides valuable insights for those looking to implement AI to support clinical decision-making and optimize resource utilization in hospitals overwhelmed by TB cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the single most deadly infectious disease, and active TB (ATB) is the main contributor to the disease spread1. Early detection and timely treatment of ATB are critical moves in interrupting TB transmission and reducing life-threatening consequences. Chest X-ray radiographs (CXR) and computed tomography (CT) are considered as fast and convenient methodologies for ATB screening and further improved diagnosis, respectively2,3,4. Chest X-ray is useful but not specific for diagnosing active TB, which could lead to missed diagnosis5, while CT is superior to Chest X-ray in identifying parenchymal lesions and showing active features of TB such as cavitation, consolidation and nodular pattern. Therefore, CT is an effective method for clarifying ambiguous findings. When a chest X-ray result is inconclusive, CT should be considered as an additional role in aiding aspiration and biopsy for active TB confirmation6,7. However, it is not easy for radiologists to accurately interpret ATB because of the heterogeneity and complexity in the pattern of the TB lesion8,9. Active tuberculosis often presents with heterogeneous and complex CT findings such as consolidation, a nodular pattern, cavitation, miliary, and pleural effusion, making it difficult to differentiate among ATB and other pulmonary diseases4,10,11,12,13, especially for doctors with limited experience. Therefore, a more accurate diagnostic tool is required. In addition, imaging interpretation can be highly dependent on radiologist expertise, and interobserver variability has often been reported in the interpretation analysis14,15,16, especially when there are co-occurrences of multiple diseases or abnormalities, such as pneumonia and pulmonary nodules.

In high-prevalence and resource-limited TB settings, radiologist shortages and heavy workloads often lead to diagnostic delays or missed diagnoses. Therefore, an AI system based on CT has the potential to support radiologists by improving efficiency, reducing diagnostic delays, and providing timely guidance for patient management. TB specialized hospital is designated by local authority to conduct the TB diagnosis and treatment, and the population it caters is TB suspected patients who are transferred from the primary or community healthcare institutions and need to get a further examination for confirmation. In the specialized hospitals, the patients who are confirmed with TB usually experience a two-stage diagnostic process: initial consultation followed by admission to TB specialized hospitals. The initial consultation is always conducted in the primary or community healthcare institutions where the patients undergo chest X-ray examinations, and if the patient is considered suspected of TB, they are then referred to TB specialized hospitals for confirmation, with both biopsy and CT imaging performed. On the other hand, as patients referred from primary care centers are usually more complex, CT examination is needed to make differentiations among active TB and other pulmonary abnormalities. Therefore, doing CT examination is the routine for TB diagnosis in specialized hospitals.

Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems have demonstrated potential in detecting TB on CXR and CT images. They can quantify the lesion features and identify the complex lesion pattern to make an automatic diagnosis7,17,18,19,20. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that radiologists’ performance can be improved if the interpretation is conducted concurrently with artificial intelligence (AI)21,22. Though AI systems have been successfully developed and validated to screen TB on CXR18,23,24,25,26, few studies have developed AI systems based on CT images to detect ATB from some main pulmonary abnormalities, nevertheless validated the algorithm independently in multiple unseen datasets. Furthermore, the performance of the AI system in a high-prevalence setting remains unknown, and the concerns about the application of AI tools in different high-prevalence settings require more evidence.

In the study, we aim to explore the potential of a proposed AI system to detect major abnormalities, including ATB, pneumonia and pulmonary nodules from normal, and to validate its power to make the differential diagnosis of ATB across three unseen CT datasets. All three datasets were collected from TB-specialized hospitals with a relatively high prevalence of TB. Specifically, the AI system is evaluated under four application scenarios. The primary scenario is finding abnormality of ATB, pneumonia and pulmonary nodules from the normal, the second scenario is detecting ATB from normal, the third scenario is detecting ATB from non-ATB (pneumonia, pulmonary nodules and normal), and the final scenario is detecting ATB from non-ATB abnormality (pneumonia and pulmonary nodules).

Methods

This study aims to perform independent validation of a well-trained AI system (I-Sight, version 2.0, Shenzhen Zhiying Medical Imaging) to detect ATB and other major pulmonary abnormalities in three CT datasets collected from TB-specialized hospitals. The system was previously developed based on a CT image dataset of 846 patients with multiple pulmonary disease/abnormality from multi-center hospitals, and in the training process, U-net was first applied to detect and segment ATB lesions, image processing methods of clustering were then applied to CT layers diagnosed as ATB lesions by U-Net to convert 2D ATB lesions at each slice into 3D lesions17. In the study, none of the three CT datasets were involved in the model development, nor had they been reported before.

Data collection

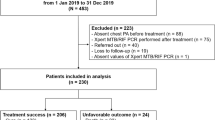

At each specialized hospital, approximately 30,000 chest CT scans were performed, of which 2% were randomly selected for subsequent inclusion and exclusion screening. The inclusion criteria were: (1) bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis; (2) complete clinical and imaging data; and (3) presence of typical imaging features. The exclusion criteria includes: (1) image artifacts; and (2) co-occurrence of multiple diseases. Finally, a total of 1741 pulmonary CT scans of ATB, pneumonia, pulmonary nodules, and normal cases were retrospectively collected from three independent hospitals (Hospital A, Hospital B, and Hospital C) during the period from January to December 2023 (Fig. 1). The study was approved by the institutional review board of Shandong Public Health Clinical Center. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of Shandong Public Health Clinical Center (Approval No. [2024-01]) owing to the retrospective nature of the study. As ATB, pneumonia, and nodules ranked in the top three kinds of pulmonary abnormalities in each hospital, roughly having a percentage of over 80% of all abnormalities, they were selected as major pulmonary abnormalities in the study. The three datasets are composed of (1) Hospital A, comprising 125 normal CT cases and 493 abnormal CT cases; (2) Hospital B, comprising 120 normal CT cases and 448 abnormal CT cases; (3) Hospital C, comprising 111 normal CT cases and 444 abnormal CT cases. More information about the distribution of abnormality is presented in Table 1.

Reference standards

In the study, the ATB patients were all bacteriologically confirmed (via positive Xpert MTB/RIF or culture-growing M. tuberculosis evidence). For pneumonia, pulmonary nodules and normal cases, two readers were involved in producing the reference standard; the first reader is the original radiological report, along with clinical symptoms and laboratory test results (if available), and the second reader is the interpretation by an intermediate radiologist (with 10 years of experience) who is blinded to the radiological reports, the consensus of two readers was considered as the reference standard. If there is a discrepancy between two readers, a senior radiologist (with 30 years of experience) would join and make the final decision.

Deployment of AI system

The proposed AI system was applied in three TB-specialized hospitals to detect ATB and other major pulmonary abnormalities and evaluate its performance as a diagnostic tool in high-prevalence settings. This clinical deployment of the AI system adhered to relevant data protection laws through de-identification of patient information and was conducted in accordance with applicable regulatory approvals and healthcare AI usage guidelines. For the CT input, the system automatically analyzes the images to identify the location of the lesion. It then produces a probability score and a predicted label for the lesion based on a predetermined operating point, where a probability score higher than the operating point is considered positive. In the current study, all cutoff points are determined based on the optimal threshold identified from the ROC curve using the Euclidean distance method, which selects the point closest to the top-left corner of the curve (0,1) in the sensitivity–specificity space. The distinct characteristic of the system is its ability to detect ATB and major multiple pulmonary abnormalities on CT scans and to differentiate between ATB and other conditions, providing clear delineation of the lesions, which enhances the interpretability of the system.

Evaluation of AI system

The AI system was evaluated in three independent TB-specialized hospitals under four application scenarios to validate its effectiveness and robustness. Each abnormal case contained only one radiological finding of three target abnormalities. The four scenarios include (1) major pulmonary abnormality (ATB, pneumonia, and pulmonary nodules) versus normal; (2) ATB versus normal; (3) ATB versus non-ATB (pneumonia, pulmonary nodules and normal); (4) ATB versus pneumonia and pulmonary nodules. In the study, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) were used to evaluate the system’s classification performance, and the comparison of the ROC curve was performed using the DeLong method (two-sided). In addition, the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score were calculated, and the two-to-two comparison of those metrics among three hospitals was performed using Pearson’s chi-square tests. Besides, for each dataset, an operation point and a range of high sensitivity thresholds (80%-90% sensitivity) were selected to observe the system’s corresponding performances in specificity. The statistical analyses were performed in R 4.3.2 and SPSS 20 software tools, and the results with P < 0.05 indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographics of the three study cohorts

The main characteristics of patients in different TB-specialized hospitals are presented in Table 1. Hospital A comprised a total of 618 patients, with 65.8% male and an average age of 57.93 ± 18.03 years. Hospital B and Hospital C have 568 (50.61 ± 19.59 years) and 555 patients (50.61 ± 19.59 years), and the male takes a percentage of 62.0% and 62.9%, respectively. The results show that there is a significant difference in age among the three settings (P < 0.001, Table 1), but their gender difference is not significant (P > 0.05, Table 1). Four types of patients in three settings are balanced in the study without any significant difference indicated. The proportion of ATB was the highest in all datasets, which was 35.0%, 38.7% and 36.2% for Hospital A, Hospital B and Hospital C, respectively. Pneumonia, pulmonary nodules and normal have a similar proportion of approximately 20% in three settings.

System effectiveness across four application scenarios

To validate the AI system’s effectiveness in TB-specialized hospitals, we validated it under four application scenarios, and the results are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Scenario I: Detecting major pulmonary abnormalities from normal. This scenario was designed as a triage step to distinguish abnormal cases from normal ones, this scenario helps prioritize critical cases requiring immediate attention while excluding a large proportion of normal cases. In clinical workflows, the AI system could serve as a first reader, reducing radiologists’ workload by rapidly filtering out normal scans. In the study, the system obtained good performance from three datasets. Hospital A differentiated abnormal and normal cases with an AUC of 0.943 (95% CI = 0.921–0.974), a sensitivity of 0.959 and a specificity of 0.832 (Figs. 2a, 3a). Hospital B and Hospital C had a comparable performance in the AUC, which is 0.923 (95% CI = 0.921–0.974) and 0.950 (95% CI = 0.921–0.974). However, compared to Hospital A, the sensitivity and specificity of the two hospitals were a little lower; they were 0.859 and 0.883 for Hospital B, and 0.946 and 0.864 for Hospital C (Figs. 2a, 3a). In each hospital, abnormal cases account for roughly 80% of the dataset. Therefore, given the imbalance between abnormal and normal cases, AUC would serve as a more objective evaluation metric than sensitivity and specificity. AUC reflects the behavior across different thresholds and focuses on the model’s ranking ability rather than absolute values, so even when there is a large disparity between positive and negative class proportions, AUC still provides a relatively stable evaluation, avoiding bias from overemphasis on one class.

Scenario II: Detecting ATB from normal. This scenario was intended for targeted ATB screening, especially in high-prevalence regions. This scenario enables early identification of suspected ATB cases from the general population to prevent potential transmission, and is also valuable for screening close contacts of confirmed ATB patients. The system’s performance improved across all datasets when the positive cases included only ATB, achieving AUCs above 0.95 in three datasets. For sensitivity and specificity, three hospitals also achieved comparable performance. The sensitivity of Hospitals A, B and C were 0.981, 0.977 and 0.925, while the specificity was 0.992, 0.992 and 0.955 (Figs. 2b, 3b). Compared to Scenario I, Scenario II shows improved specificity, indicating that the system could distinguish ATB from normal cases more accurately than it could distinguish pneumonia or nodules from normal. Consequently, more normal cases were misdiagnosed as positive in Scenario I.

Scenario III: Detecting ATB from non-ATB. This scenario simulates a broader differential diagnosis situation in which ATB needs to be distinguished from other common non-TB abnormalities and normal findings. It reflects real-world diagnostic complexity in TB-specialized hospitals. When the negative cases included not only normal but also other non-ATB abnormal, there was a decrease in the system’s classification performance compared to Scenario I and Scenario II. As shown in Fig. 2c, the AUC of Hospitals A and B remained above 0.9, while Hospital C dropped to 0.829. Similarly, we observed a decrease in both sensitivity and specificity. The system achieved sensitivities of 0.861, 0.932, and 0.786, with corresponding specificities of 0.888, 0.787, and 0.759 for Hospitals A, B and C, respectively (Fig. 3c). This may be because ATB, pneumonia, and nodules exhibit similar radiological features in CT images, and these overlapping features increase classification difficulty. Additionally, the proportion of negative cases was higher than that of positive ones, which may have caused the system to become biased towards predicting the negative class.

Scenario IV: Differentiating ATB from other abnormalities. This scenario focused on differentiating ATB from other lung abnormalities in the absence of normal cases. This scenario reflects situations where patients suspected of TB based on initial imaging in primary or community healthcare settings are referred to TB-specialized hospitals for confirmation. In this context, the AI system could serve as a second reader, providing radiologists with additional diagnostic support to refine and validate their assessments. The system’s ability to reduce such clinically significant misdiagnoses between ATB and other abnormalities can directly impact both individual patient outcomes and broader public health efforts. Pneumonia and nodules were used as negative cases in the test, as shown in Figs. 2d and 3d. Compared to Scenario III, we observed a further drop in the system’s performance when the normal cases were excluded, especially in terms of AUC (0.762–0.906) and specificity (0.650–0.863). However, sensitivity remained consistent; they were 0.838, 0.932 and 0.786 for Hospitals A, B and C. These results showed that the composition of negative cases did not affect the system’s ability to identify ATB. Nonetheless, the absence of normal cases in the negative class weakened the distinction between positive and negative features, decreasing AUC and specificity. From the analysis of positives and false negatives, we found that when false positives were nodules, they were often due to the presence of nodular lesions within tuberculosis foci, leading nodules to be misclassified as tuberculosis. Conversely, when false negatives were nodules, they were usually caused by the presence of tuberculous granulomas. In addition, mutual misclassification between tuberculosis and pneumonia was typically attributable to patchy opacities and tree-in-bud patterns. From a clinical perspective, false positives may lead to unnecessary anti-tuberculosis treatment and delay appropriate management of nodules or pneumonia, while false negatives may postpone timely anti-tuberculosis treatment and increase the risk of ongoing transmission.

System robustness across four application scenarios

To test the generalization of the AI system across multiple clinical settings, we conducted independent validations at three hospitals and compared the results between any two of them. Figure 4a and b show that when the system was used to identify abnormalities (Scenario I) or ATB (Scenario II) from normal cases, there was no significant difference in AUC and specificity across the three hospitals. Additionally, the differences in accuracy, sensitivity and F1 score were not significant between Hospitals A and C in Scenario I, nor between Hospitals B and C in Scenario II.

When the system was applied to differentiate between ATB and other conditions, including common abnormalities with (Scenario III) and without (Scenario IV) normal cases, we observed a similar trend in the significance of the five evaluation metrics across any two hospitals (Fig. 4c and d). Specifically, there were no significant differences in AUC, accuracy, and F1 score between Hospitals A and B, no significant difference in sensitivity between Hospitals A and C, and no significant difference in specificity between Hospitals B and C. However, the system showed a more significant performance drop at Hospital C compared to Hospitals A and B, which ultimately impacted the system’s overall robustness. This may be because ATB cases from Hospitals A and B exhibited more typical and consistent radiological features of ATB (Fig. 5a and b), while images from Hospital C presented more complicated and ambiguous findings that confused the system (Fig. 5c).

Matching performance to high sensitivity targets

In the TB-specialized hospital, we prioritize high sensitivity to minimize missed diagnoses and help prevent the spread of TB. However, increasing sensitivity may lead to more false positive cases, potentially increasing radiologists’ workload as they re-evaluate the system-labeled “positive cases.” Therefore, increasing sensitivity without a significant drop in specificity is desirable. In the study, we applied a high sensitivity ranging from 0.8 to 0.9 to diagnose and observe the changes in specificity. As shown in Table 2, the results indicated that the system achieved comparable, or even better, specificity across a range of high sensitivities compared to the operating point. Even when sensitivity was set to 0.9, the system maintained good specificity, except for Hospital C in Scenario III and Scenario IV. This may be explained by the more complicated and ambiguous radiological findings observed in the images from Hospital C, as previously noted.

Discussion

We validated a well-trained AI system on three TB-specialized hospitals to test its clinical utility in detecting ATB from major pulmonary abnormalities of pneumonia and nodules on CT images. Quickly distinguishing ATB from inactive or healed TB in areas with a high TB burden is essential. This helps prevent TB transmission and ensures that further examination and medication are applied where necessary, thus avoiding resource waste, as inactive and healed TB cases require no additional examination24. In the study, the AI system correctly identified ATB patients, achieving AUCs ranging from 0.762 to 0.996, with negative cases being single-class or multi-class. This performance is comparable to recently reported CT-based ATB detection27, in which only a single class of inactive TB was considered negative. Another feasibility study developed a CT-based system for the binary classification of ATB and non-ATB, with results showing AUCs ranging from 0.908 to 0.961 in the internal test, and 0.884 to 0.946 in the external test19. Other studies have focused on differentiating ATB from normal conditions28 and community-acquired pneumonia29, both of which achieved good performance with accuracy or AUC values around 0.9. It may be easier for an AI system to distinguish TB from a single type of abnormality, as it reduces the complexity of the classification task. However, our study included a broader range of radiological findings, both typical and atypical, of pneumonia and pulmonary nodules, resulting in a more challenging dataset for the system’s evaluation. As a result, our system may be more applicable than similar ATB detection tools that focus on a single differentiation task19,29.

Generalizability to different populations is vitally important for AI system evaluation. Understanding AI performance on unseen datasets is essential for further application in real clinical settings. In this work, to evaluate the AI system’s robustness, we tested it on three independent hospitals, which have never been reported or used for training before. The results showed that the AI system generalized well across these three unseen clinical settings, demonstrating acceptable performance. At least one pairwise comparison for each evaluation matrix showed no significant difference when the system was applied in different scenarios. Especially in Scenario I and Scenario II, no significant difference was indicated in AUC and specificity between any two hospitals. When the system was applied in Scenario III and Scenario IV, we observed a more significant drop in Hospital C compared to Hospitals A and B, which impacted the system’s overall robustness. CT images may explain this with more complex radiological findings.

It is important for implementers to select the threshold abnormality score specific to their setting30. In the study, we applied a high sensitivity threshold for the system to identify ATB in specialized hospitals to minimize the risk of missing any potential ATB cases. The results showed that the system maintained good specificity at a high sensitivity range of 0.8–0.9, allowing it to identify high-risk ATB individuals for further examination while maintaining the overall specificity of the program.

Based on the fact that the diagnostic performance of the AI system may be affected by TB prevalence31, we prepared three datasets that are balanced among each other in the proportion of normal and abnormal CT images. In TB-specialized hospitals, approximately half of the abnormalities were ATB; therefore, we collected ATB images at a ratio of 2:1:1 relative to pneumonia and pulmonary nodules, respectively. This approach simulates the diagnostic challenges AI systems face in realistic and complex clinical settings, where the system must differentiate between ATB and other pulmonary conditions, especially high TB prevalence in specialized hospitals. This work may be the first attempt to explore the usefulness of the AI system in identifying ATB in areas with high TB burden. Previous studies have mostly evaluated the performance of AI systems for TB detection in the screening scenario where TB prevalence is low, and most of the population is healthy18,32. The results showed an AUC of over 0.9 in Scenarios I and II, and around 0.8 in Scenarios III and IV, for three specialized hospitals. It suggests the AI system may have great potential for ATB detection in CT images in TB high-burden settings.

Several deep learning (DL) approaches have achieved great performance in detecting ATB from chest X-ray radiographs, and multiple independent validation and wide applications in external datasets have been performed. Choi et al.24 developed a DL model to classify the ATB and inactive tuberculosis in internal and external datasets. The result showed that the proposed model performed well in the internal test, and a slight decrease was observed in the external test (AUC, 0.98 vs. 0.81–0.88). In Sahar et al.33, A DL system has been proposed and tested on five datasets, including countries with low and high TB burdens (TB positive proportion range of 10–48%), and the system consistently performed well across all datasets. Moreover, the AI-based model for ATB detection was reported to outperform most physicians in both image-wise classification and lesion-wise localization21,25 and obtained a comparable performance to the expert readers31. Although there have been some works that explored the potential of AI for detecting ATB in chest X-ray radiographs, fewer studies have been conducted on CT images34; this may be due to the limited availability of public ATB CT datasets compared to chest X-ray radiographs datasets, and it is generally a challenge for the model development without sufficient large and well-annotated datasets. The study validated the effectiveness and robustness of an AI system in identifying ATB in CT images, and the results demonstrated the system achieved an acceptable performance compared to similar models proposed for chest X-ray radiographs. This suggests that the AI system can effectively detect ATB in CT images, providing a reliable tool for settings where CT imaging is more readily available or preferred for diagnosing complex cases of ATB.

There are several limitations in the study. First, individuals with healed TB were not included. Differentiating ATB from healed TB could help prevent unnecessary medication use in non-infectious individuals, and further investigation is warranted for the task. Second, the AI system was used to classify ATB from other abnormalities and normal conditions, without assessing disease severity, and detailed image acquisition protocols were not uniformly available across centers. Further training will be conducted for the system to incorporate disease severity assessment with complete acquisition information. Third, since the dataset was retrospectively collected, the included cases may not fully represent the real-time and broader patient population, potentially introducing possible spectrum bias and selection bias. Additionally, the reference standards were established by consensus of radiologists based on radiology or pathology reports, and in some cases, incomplete laboratory information may have influenced the reference standard. Fourth, external validation beyond the three participating centers was not conducted, limiting generalizability to primary care settings; moreover, comparative analysis with radiologists or existing CAD tools and cost-effectiveness evaluation were not performed, and these aspects warrant investigation in future research.

Future work will involve prospective validation in more representative populations, integration of the AI system into radiologists’ routine workflows, and evaluation in community and low-resource settings. Furthermore, assessing the impact of AI-assisted decision-making on patient management and outcomes will be an important direction to demonstrate its clinical utility.

In conclusion, an AI system was validated across three independent hospitals to evaluate its utility and generalizability for identifying ATB. The results showed that AI can effectively identify ATB in CT images within TB-specialized hospitals. Integrating AI into specialized TB hospital workflows can follow different strategies to enhance diagnostic accuracy and streamline patient management. One approach is using AI as a first reader, where the system pre-diagnoses CT scans immediately upon imaging acquisition. Alternatively, AI can function as a second reader, providing radiologists with an additional layer of analysis. After a radiologist’s initial interpretation, AI can highlight suspicious areas, acting as a safeguard against missed diagnoses and reducing inter-reader variability. This evaluation provides valuable insights for those looking to implement AI to support clinical decision-making and optimize resource utilization in hospitals overwhelmed by TB cases.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Millington, K. A. et al. The 2023 UN high-level meeting on tuberculosis: renewing hope, momentum, and commitment to end tuberculosis. Lancet Resp. Med. 12, 10–13 (2024).

Bommart, S. et al. Differentiating between active and latent tuberculosis with chest computed tomography. Diagn. Interv. Imag. 102, 605–610 (2021).

He, W. et al. Use of low-dose computed tomography to assess pulmonary tuberculosis among healthcare workers in a tuberculosis hospital. Infect. Dis. Poverty 6, 68 (2017).

Nachiappan, A. C. et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis: Role of radiology in diagnosis and management. Radiographics 37, 52–72 (2017).

Ryu, Y. J. Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: recent advances and diagnostic algorithms. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. (Seoul) 78, 64–71 (2015).

Kim, W. S. et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in infants: radiographic and CT findings. Am. J. Roentgenol. 187, 1024–1033 (2006).

Yan, C. et al. A fully automatic artificial intelligence-based CT image analysis system for accurate detection, diagnosis, and quantitative severity evaluation of pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur. Radiol. 32, 2188–2199 (2022).

Cadena, A. M., Fortune, S. M. & Flynn, J. L. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 691–702 (2017).

Urbanowski, M. E., Ordonez, A. A., Ruiz-Bedoya, C. A., Jain, S. K. & Bishai, W. R. Cavitary tuberculosis: The gateway of disease transmission. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, e117–e128 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Radiologic features of small pulmonary nodules and lung cancer risk in the national lung screening trial: A nested case-control study. Radiology 286, 298–306 (2018).

Light, R. W. Update on tuberculous pleural effusion. Respirology 15, 451–458 (2010).

Zhang, K. et al. Content-based image retrieval with a convolutional siamese neural network: Distinguishing lung cancer and tuberculosis in CT images. Comput. Biol. Med 140, 105096 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Establishment of a CT image radiomics-based prediction model for the differential diagnosis of silicosis and tuberculosis nodules (in Chinese). Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 37, 707–710 (2019).

Yoon, S. H. et al. Interobserver variability in lung CT screening reporting and data system categorisation in subsolid nodule-enriched lung cancer screening CTs. Eur. Radiol. 31, 7184–7191 (2021).

Çallı, E., Sogancioglu, E., van Ginneken, B., van Leeuwen, K. G. & Murphy, K. Deep learning for chest X-ray analysis: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 72, 102125 (2021).

Johnson, J. & Kline, J. A. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of the interpretation of pediatric chest radiographs. Emerg. Radiol. 17, 285–290 (2010).

Ma, L. et al. Developing and verifying automatic detection of active pulmonary tuberculosis from multi-slice spiral CT images based on deep learning. J. Xray Sci. Technol. 28, 939–951 (2020).

Zhou, W. et al. Deep learning-based pulmonary tuberculosis automated detection on chest radiography: Large-scale independent testing. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 12, 2344–2355 (2022).

Nijiati, M. et al. Deep learning based CT images automatic analysis model for active/non-active pulmonary tuberculosis differential diagnosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1086047 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Distinguishing infectivity in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis using deep learning. Front. Public Health 11, 1247141 (2023).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e191095 (2019).

Lin, G. et al. in Proc. SPIE. 124670D.

Bista, R. et al. Advancing tuberculosis detection in chest X-rays: A YOLOv7-based approach. Information 14, 655 (2023).

Choi, Y. R. et al. Chest radiography of tuberculosis: Determination of activity using deep learning algorithm. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. (Seoul) 86, 226–233 (2023).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based automatic detection algorithm for active pulmonary tuberculosis on chest radiographs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, 739–747 (2019).

Kim, S. et al. Deep learning in multi-class lung diseases’ classification on chest X-ray images. Diagnostics (Basel) 12, 915 (2022).

Bai, Q. et al. Representative slice selection and multi-view projection learning for pulmonary tuberculosis infectiousness identification using CT volume. IEEE Access 12, 1374–1385 (2024).

Wang, S.-H., Govindaraj, V., Gorriz, J. M., Zhang, X. & Zhang, Y.-D. Explainable diagnosis of secondary pulmonary tuberculosis by graph rank-based average pooling neural network. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-021-02998-0 (2021).

Han, D. et al. Development and validation of a 3D-convolutional neural network model based on chest CT for differentiating active pulmonary tuberculosis from community-acquired pneumonia. Radiol. Med. (Torino) 128, 68–80 (2023).

Qin, Z. Z. et al. Tuberculosis detection from chest x-rays for triaging in a high tuberculosis-burden setting: An evaluation of five artificial intelligence algorithms. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e543–e554 (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Deep learning to determine the activity of pulmonary tuberculosis on chest radiographs. Radiology 301, 435–442 (2021).

Lee, J. H. et al. Deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for active pulmonary tuberculosis on chest radiographs: diagnostic performance in systematic screening of asymptomatic individuals. Eur. Radiol. 31, 1069–1080 (2021).

Kazemzadeh, S. et al. Deep learning detection of active pulmonary tuberculosis at chest radiography matched the clinical performance of radiologists. Radiology 306, 124–137 (2023).

Li, X. et al. A deep learning system that generates quantitative CT reports for diagnosing pulmonary Tuberculosis. Appl. Intell. 51, 4082–4093 (2021).

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Shenzhen Science and Technology Program [Grant No.: KQTD2017033110081833; JCYJ20220531093817040], the Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project [Grant No.: 2023A03J0536; 2024A03J0583; 2024A03J0795], the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Program Project [Grant No.: 2024SGGZ059], and the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province [Grant No.: 2021SFGC0504].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W., Z.Z. and G.L. conceptualized and designed the study and methodology. Q.W. performed the experiments and wrote the main manuscript text. L.X., X.G. and Q.X. collected samples and analyzed the research data. G.L. and H.G. provided work supervision. All authors reviewed and validated the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Xia, L. et al. Using AI system to detect active tuberculosis in a high-prevalence setting on CT scans: a multi-center study. Sci Rep 15, 39546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23172-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23172-y