Abstract

The study investigates the effectiveness of Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors in measuring real-time aggregation forces across soils with varying particle sizes. Traditional measurement techniques are invasive, static, and lack real-time capability, making FBG sensors a promising technology for real-time monitoring. A laboratory experiments was conducted using FBG sensors embedded within soil samples of different particle sizes (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.18 mm, and 2 mm) with aggregation forces measured under controlled conditions simulating various water content levels. Data were collected continuously over a specified period to assess the dynamic response of the soils. The results showed a strong correlation between soil particle size and aggregation force, with larger particles exhibiting higher compaction-derived aggregation forces due to enhanced mechanical interlocking and reduced void space under load, while finer particles showing greater cohesion from higher surface area-to-volume ratios. This distinction arises because coarse particles (2.0 mm) transmit forces primarily through gravitational settling and frictional resistance, whereas fine particles (0.125 mm) rely on cohesive surface interactions. Wavelength shifts recorded by FBG sensors confirmed their reliability in detecting force changes, with finer soils yielding more pronounced sensor responses. These findings have significant implications for soil health assessment, agricultural management, and environmental engineering, particularly in optimizing tillage and soil stabilization strategies. The study demonstrates the potential of FBG sensors for real-time soil monitoring and recommends further exploration of sensor integration with field-scale applications and varying environmental conditions to enhance soil management practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil aggregation is fundamental to soil health and functionality, as it influences properties such as porosity, water retention, nutrient availability, and structural stability1,2,3. Aggregates, formed by the cohesive forces among soil particles, play a key role in enhancing soil resilience against erosion and mechanical stress2. Different soil particle sizes exhibit varying responses to applied stresses and loads. Therefore, monitoring soil pressure in different soil particle sizes is crucial for accurate assessment of soil stability and behavior. However, understanding the forces holding these aggregates together—referred to as aggregation forces—is complex, largely due to the heterogeneity of soil and the diversity of its particle sizes4,5. These forces vary not only across different soil types but also according to environmental conditions like moisture, temperature, and applied pressures, which can influence both short-term and long-term soil stability6.

Existing methods for measuring soil aggregation, strength and stability face significant limitations, particularly in real-time and relation to specific soil particle sizes7. Traditional methods, such as unconfined compression testing, penetration resistance measurement, and shear strength testing, are static and invasive, failing to capture dynamic changes in aggregation forces over time or under varying environmental conditions8,9. Penetrometers, which measure soil resistance to penetration, offer valuable data on compaction and soil hardness but do not capture the nuanced differences in cohesion between soil aggregates of varying particle sizes10,11. Moreover, traditional methods do not provide continuous data, making it difficult to monitor changes in aggregation forces in response to dynamic factors like rainfall or mechanical loading from machinery12,13. This lack of real-time monitoring means that researchers and soil managers miss crucial temporal variations in aggregation forces, which are often essential for understanding soil behavior under natural or managed conditions. Another significant limitation of current methods is their inability to isolate and measure the specific influence of particle size on aggregation forces14. Soil particle size distribution has a pronounced effect on the stability of soil aggregates, with finer particles tending to form stronger, more cohesive bonds than coarse particles, which affects overall soil structure12,15,16. While some techniques, such as the aggregate stability test, provide indirect measurements of soil stability, they do not offer quantitative insights into how aggregation forces vary specifically with different particle sizes. As a result, there is a knowledge gap in understanding the direct impact of particle size on soil cohesion, which hinders the development of targeted soil management strategies based on soil composition17. Hence, the need for using advanced and highly sensitive sensor such as Fiber Bragg Grating, which will be more reliable, accurate and real time monitoring.

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors offer a novel method to monitor soil aggregation forces in real-time across various particle sizes18. FBG technology provides high precision and sensitivity in measuring forces and strains, making it ideal for capturing real-time changes in aggregation forces within soils of varying particle sizes19,20,21. FBG sensors work by detecting wavelength shifts in light passing through optical fibers, allowing for minimal interference with soil structure and environmental conditions13,22. Unlike traditional methods, FBG sensors provide continuous, non-destructive data, enabling a real-time monitoring approach that can reveal dynamic changes in aggregation forces under field conditions23. This makes FBG sensors valuable for observing forces variation across soil samples with different particle sizes, providing real-time data necessary for assessing soil health and stability in field settings. FBG sensors can also be embedded in the soil to monitor force changes over long periods, providing insights into the dynamic behavior of soil aggregation under natural and agricultural pressures22,23. This study overcomes three fundamental limitations of traditional soil measurement methods—their static, invasive, and particle-insensitive nature—by developing an FBG-based platform for real-time aggregation force monitoring across five soil textures (0.125–2.0 mm). As detailed in Table 1, our approach advances beyond prior FBG studies by: (1) resolving particle-size dependencies through multi-depth sensing, (2) compensating for moisture effects (validated at 18.5% w/w), and (3) correlating forces with SEM-verified microstructures. These innovations establish FBG technology as a field-ready tool for in situ soil health assessment, enabling data-driven management of compaction, tillage, and erosion control. The resulting dataset provides the first comprehensive analysis of texture-dependent aggregation forces, bridging the gap between laboratory precision and agricultural practice.

This paper begins with a literature review covering the role and relationship between soil particle size and aggregation, the limitations of current measurement methods, and the advantages of FBG sensors in real-time force monitoring. The experimental methods section outline the setup and calibration of FBG sensors for aggregation force measurement, while the results, discussion and conclusion sections will analyze findings, trends observed in real-time force data across different soil particle sizes and their implications for soil stability, health, and management. This study aims to provide a foundational understanding of aggregation forces in varied particle sizes, laying the groundwork for future research and practical applications in soil health monitoring, management and environmental engineering.

Materials and methods

Materials

The materials used in this study include FBG sensors, various soil types with differing particle sizes (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.125 mm, and 2.0 mm), a soil column apparatus, and measurement equipment (demodulator and computer system). The soil samples used in this study were collected from the experimental farm of Henan Agricultural University, located in Jinshui District, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China. The soils were classified according to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) (ASTM D2487) and USDA Soil Texture Classification. The particle sizes selected (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.18 mm, and 2.0 mm) represent key fractions of sand (coarse, medium, fine) and silt (per ASTM D422-63 for particle size analysis). Index properties were tested were determined following ASTM standards: D854 for specific gravity, D2216 for moisture content, and D4318 for Atterberg limits. The grain size distribution was determined via sieve analysis (ASTM D6913 for particles > 75 μm) and hydrometer analysis (ASTM D7928 for particles < 75 μm) as summarized in Table 2. The FBG sensors were chosen for their high sensitivity to strain and temperature changes, which are critical for detecting aggregate forces in soil25. The soil types selected for the experiment included fine sand, coarse sand, silt, and clay, each representing different particle size distributions. A temperature controlled chamber was maintained during the testing phase to control the environment. The fiber cross-section was scanned using a focused ion beam etching system (FEI, Quanta 3D-FEG) to modify it (Fig. 1a). The modified region was etched in the y direction using a FIB (Focused Ion Beam), confirming an FBG pitch of 0.535 μm, half of the phase-mask pitch (1.07 μm) (Fig. 1b). The fiber cross-section showed a modification static exposure of approximately 20 μm, with a curvature along the scanning axis that follows the curvature of the fiber entrance face due to refraction (Fig. 1c). The FBG design length can be accurately changed by scanning the narrow reshaped beam 500 μm along the y direction at a constant speed using a linear air bearing stage26. The fiber cross-section was then post-processed using a FIB, confirming the FBG pitch of 0.535 μm, which is half the phase-mask pitch (Fig. 1b).

Soil column design

The soil column was designed to facilitate the application of controlled loads while allowing for the accurate measurement of force transmission through the soil matrix. The column designed was made with open window in the front to allow the easy removal of the tested soil after the readings which will also prevent the inserted FBG sensor from damage (Fig. 2). The column was then placed on the constructed profile holder which entails the guide rail/slider, FBG sensor holder, column placement part, sample pad holder and the lifting screw which enable the adjustment of the FBG sensor after inserted in the soil sample (Fig. 3). The total height of the designed experimental set-up is 80 cm with 30 cm width. In addition, a drainable perforated base was built which allows for the preservation of the soil during the loading test.

Preparation of soil sample

Soil sample preparation

Prior to experimentation, each type of soil sample was prepared by drying it in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h to remove moisture content. This ensures the soil structure was equilibrated and ready for accurate force assessments. After drying, soils were sieved through standardized mesh screens (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.125 mm, and 2.0 mm) to achieve desired particle size distributions accurately. These sizes were chosen to represent a range from fine to coarse particles, allowing for a comparative analysis of aggregation forces across varying textures. Specific gravity and moisture content were measured before the experiments. Grain size distribution curves for the tested soils are presented in Fig. 4. These curves validate the USCS and USDA texture classifications provided in Table 2 and illustrate the distinct separation between particle-size fractions, which is essential for isolating particle-size effects in aggregation force measurements. The data confirm the USCS and USDA texture classifications in Table 2, showing clear separation between size categories and validating the targeted soil fractions used for controlled aggregation force testing.

Grain size distribution curves for the five particle-size fractions tested (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.18 mm, and 2.0 mm), plotted as cumulative percent passing versus particle diameter on a semi-logarithmic scale. The curves are based on ASTM D6913 (sieve analysis) for particles >75 μm and ASTM D7928 (hydrometer analysis) for particles <75 μm, adjusted to reflect the narrowly graded particle fractions used in the experiment.

The compaction behavior of each particle-size fraction is presented in Fig. 5. Each curve follows the characteristic parabolic form observed in Standard Proctor tests, with maximum dry density (MDD) values occurring at the respective optimum moisture content (OMC) which shows that finer fractions require higher moisture content to reach their MDD due to increased surface area and water adsorption, while coarser fractions achieve higher densities at lower OMC because of reduced water demand and more efficient particle interlocking.

The Standard Proctor compaction curves for the five soil fractions tested (0.125, 0.425, 0.85, 1.18, and 2.0 mm), showing the relationship between dry density and moisture content. The red points indicate the maximum dry density (MDD) at the corresponding optimum moisture content (OMC) for each fraction, as determined in accordance with ASTM D698. The finer fraction (0.125 mm) exhibits a higher OMC (17.2%) and lower MDD (1.48 g·cm⁻³), whereas coarser fractions such as 2.0 mm have lower OMC (12.4%) and higher MDD (1.60 g·cm⁻³), reflecting differences in particle packing and water demand.

Aggregate formation

Aggregates were formed for each particle size category by compacting the sieved soil in the experimental column using a standardized protocol. The soil was compacted in three equal layers (total 350 g per column) using a 500 g weight dropped from 10 cm height five times per layer. This achieved a consistent bulk density of 1.45 ± 0.05 g/cm³, verified using the core method27. No binding agents were used, ensuring particle size and moisture interactions alone influenced aggregation forces. After compaction, 130 mL of water was uniformly applied to simulate field moisture conditions. The 130 mL of water applied after compaction was calculated based on the target degree of saturation derived from the soil’s measured porosity and bulk density, ensuring that the applied water content corresponded to near-saturated conditions without excessive ponding. Preliminary laboratory trials indicated that this volume was sufficient to uniformly wet the entire 20 cm × 10 cm column to its maximum water-holding capacity. The saturation condition was confirmed by visual observation of water appearing at the bottom of the column and by ensuring the volumetric water content approached the calculated value for 100% saturation according to ASTM D698 guidelines. The chosen value of 130 mL also matches the volume required to reach field capacity for similar soil textures in related studies16. This compaction approach was adapted from the ASTM D698-12e2 Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort, scaled proportionally to the reduced column dimensions and sample mass in order to deliver an equivalent compaction energy per unit volume while minimizing particle breakage, particularly in coarse fractions. The applied 500 g weight dropped from 10 cm height five times per layer was calculated to approximate the standard compaction effort when normalized to the column volume, ensuring consistency across all particle-size treatments.

Experimental setup and procedures

The experimental setup involved placing the FBG sensors at predetermined depths within the soil column to measure strain induced by applied loads. Soil samples were placed in a cylindrical column with a height of 20 cm and a diameter of 10 cm, providing a controlled environment for aggregation force measurement. Each column setup contained a total of 700 g of soil, with 350 g placed below the FBG sensor and 350 g above (Fig. 6). To simulate natural loading conditions, 130 mL of water (18.5% w/w moisture content) was applied per column. This volume was determined through preliminary saturation tests to achieve optimal aggregation conditions without saturation, corresponding to 60–70% water-holding capacity for the tested particle sizes (0.125–2.0 mm). Water was applied uniformly via spray applicator at 5 mL/min, with post-application moisture content verified as 18.3 ± 0.7% gravimetrically. Load increments were applied systematically up to a maximum load determined by preliminary tests while monitoring real-time data from the FBG sensors using an optical interrogator connected via fiber optic cables (Fig. 7). Two FBG sensors (OS1100, Micron Optics) were deployed at 5 cm and 10 cm depths in the soil column to enable depth-resolved force measurements. This dual-sensor configuration provided redundancy for data validation and compensated for potential soil heterogeneity. Experiments were conducted at a controlled room temperature of 24 °C, with measures taken to ensure minimal fluctuations in temperature and humidity during each test. Each soil sample was carefully leveled within the column to maintain uniform density and minimize variations in aggregation force distribution. The FBG interrogator recorded strain data at 10 Hz, capturing wavelength shifts with ± 5 pm resolution. This sampling rate was selected to resolve rapid force variations during dynamic loading (water infiltration and mechanical compaction) while avoiding aliasing, per the Nyquist criterion for our observed < 2 Hz dominant frequencies; maintain manageable data volumes (< 1 GB/hour) for long-duration tests; and match the 8 ms response time of the FBG sensors (per manufacturer specifications. The static tests used the same rate for consistency, with post-processing downsampling to 1 Hz for quasi-static analysis. Data were time-synchronized with load application events using hardware triggers.

FBG sensors principle and calibration

Fibre bragg grating working principle

A FBG is the periodic permanent variation of the refractive index over a length of optical fiber22,23. This is accomplished by exposing the optical fiber to an interference pattern of high-intensity ultraviolet light, which increases the photosensitivity of the silica. When the optical fiber is illuminated with a broadband light source, a narrow band of wavelengths is reflected as shown in Fig. 8. FBG works on a straightforward concept: measuring the variation in the Bragg wavelength (λB) which is proportional to the effective refractive index (ηeff) and the periodicity (\(\Lambda\))28. Bragg wavelength is defined as:

This enables any change in fiber properties induced by a perturbation to change the refractive index, and grating pitch (λ) changing the resonance (Bragg) wavelength and a measure of this shift will result in the detection and quantification of the physical perturbation. The fundamental relationships of structural sensing for an FBG sensor is described in Eq. 229,30. These equation follows the thermo-optic theory of Erdogan, with strain sensitivity coefficients (\(\:{\text{S}}_{\epsilon\:}{\text{S}}_{T}\)) calibrated per manufacturer specifications.

where Sε = 0.8 × 10−6/µε and ST = 7.0 × 10−6/◦C are the strain and temperature sensitivities, respectively, at 1550 nm wavelength, ε and T are the respective change in strain and temperature changes in forces induce strain (є), causing a shift in the Bragg wavelength (∆λB), calculated as:

Where k is the calibration constant determined during the initial calibration phase. The appearance of changes in the temperature of the ΔT and the deformation of the Δε causes a change in the Bragg wavelength in accordance with the dependence31:

Response of FBG to strain

Differentiating Eq. 1, we obtain:

Substitution of ∧ and \(\:{n}_{eff}\:\)from Eq. 1 gives:

where d∧/∧ is strain (ɛ). The \(\:{n}_{eff}\) changes induced by strain (ɛ) can be given as:

Thus, we get:

where Pe is an effective strain-optic constant, P11 and P12 are the strain-optic tensor components and υ is the Poisson’s ratio. Equation (5) to (8) originates from the strain-optic theory of Butter & Hocker32, incorporating the effective strain-optic constant (\(\:{\text{P}}_{e}\)) formulation33. The Poisson’s ratio (υ) values align with ASTM D7012-14e1 for compacted soils.

Response of FBG to temperature

Both the periodicity and effective refractive index of the FBG sensors change due to the temperature change by which there is a wavelength shift. Differentiating Eq. 6 regarding temperature led to:

Substitution of ∧ and neff from Eq. 9 gives:

that is,

Where: is the thermo-optical tensor coefficient, and α is the thermal expansion coefficient11.

Sensor setup and specifications

A two-point Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor was employed to monitor soil aggregation forces in real time. The sensor points were positioned with a 5 cm interval to capture variations in force at two distinct depths within the soil column. The FBG sensors used in this study were model SM125 devices manufactured by Micron Optics, Inc. (Atlanta, GA, USA). These sensors were purchased through the company’s authorized Chinese distributor, Beijing SinoFiberOptics Technology Co., Ltd., in April 2024. Each sensor features a 10 mm grating length with Ormocer polymer coating suitable for soil embedding, operating within a spectral range of 1525–1565 nm and temperature range of −20 °C to 80 °C. The sensor specifications and performance characteristics are documented in the manufacturer’s technical manual. The selected FBG sensor as crucial for detecting polymerization in soil because of its high sensitivity to strain and temperature changes25 which enhanced the mechanical strength. During this research, the FC/APC connector type was used together with the interrogator unit, and it was noted that this type of connector is considered the best for FBG sensing owing to its minimal return losses. The FBG probe and packaged FBG sensor are illustrated in Fig. 9.

The FBG sensor was configured with an optical fiber sensitive to minute wavelength shifts (∆λB), enabling precise detection of force changes as soil aggregates interacted with the sensor under varying loads. The FBG sensors (OS1100, Micron Optics) provided a strain resolution of 1 µε and accuracy of ± 5 µε (0–10,000 µε range), with temperature resolution of 0.1 °C and accuracy of ± 0.5 °C (5–40 °C range)34. The wavelength resolution was 1 pm, translating to a force resolution of 0.05 N after calibration per ASTM D8292-20. Static validation via deadweight tests (0–200 N) confirmed R²=0.998 against ISO 376:2011 standards, while dynamic testing at 10 Hz showed < 3% RMS error versus reference strain gauges. These specifications were maintained under 18.5% soil moisture conditions (ASTM D2216), as documented in the manufacturer’s technical sheets and independently verified by35.

Calibration procedure and placement in soil column

Calibration of the FBG sensor was conducted prior to embedding it in the soil to ensure accuracy in force measurement. A series of known forces was applied to the sensor in a controlled setup, and the resulting wavelength shifts were recorded. Temperature compensation techniques were applied to minimize environmental interference, and calibration factors were determined for converting wavelength shifts into force values. The calibration constant k (in nm/N) was determined from the linear relationship between force and wavelength shift. The FBG sensor was embedded within the center of the soil column, positioned horizontally at a depth of 10 cm from the base. The two sensing points were located at 5 cm and 10 cm from the bottom of the column, allowing for simultaneous measurement of forces at different soil layers.

Force measurement procedure and data analysis

Data acquisition and signal processing

The FBG sensor collected real-time data on force changes as the 130 ml of water was applied to each soil sample. The sensor’s data acquisition rate was set at 100 Hz, capturing force responses at high resolution (wavelength resolution: 1 pm). Data logging software was used to continuously monitor wavelength shifts (∆λB), which were later converted to force values based on calibration factors (k = 0.05 nm/N ± 2%) established from the initial setup. The applied force F was then derived using the sensor’s calibration constant k (Eq. 6) which implements the sensor calibration protocol per ISO 18674-2:2017 for geotechnical instrumentation. The temperature compensation in Eq. (7) follows the dual-parameter algorithm36

Sensor data were combined using vector summation (√(Δλ₁² + Δλ₂²)) to characterize bulk soil response. This approach integrates force distributions across depths while improving signal-to-noise ratio through spatial averaging. Collected data were processed to remove noise and environmental interference. Filtering techniques, such as low-pass filtering, were applied to ensure that only relevant force measurements were analyzed13,38. Any minor wavelength fluctuations unrelated to soil particle forces were disregarded, providing a clear profile of aggregation force changes over time as moisture infiltrated the soil column. Temperature correction was performed using:

where is the temperature sensitivity of the FBG sensor, and ∆T represents temperature change. The compaction force F for each particle size can be related to the applied pressure and the effective area of contact:

Where σ is the stress exerted on the soil column18, A is the cross-sectional area of the soil column (in this setup, \(\:A=\pi\:{r}^{2}\) where r is the radius of the column, 5 cm or 0.05 m). Given that A ≈ 0.00785m2, the force measured by the FBG sensor is directly proportional to the applied stress. The force exerted by aggregates can be modeled using the following equation derived from classical mechanics:

where C is the area of contact between particles, Δ\(\:x\) is the displacement due to external loading37. However, Eq. 16 indicates the theoretical models of soil mechanics where the stress is distributed:

Where σ is stress (Pa or N/m²), F: Applied force (N) and A is Contact area (m²). Furthermore, the various soil particle sizes in detecting aggregate force behavior can be explained through dynamic modeling approaches such as the Mass-Spring-Damper system model39, where each particle size can be represented as a distinct mass with specific damping characteristics influenced by moisture levels and compaction states:

where m represents mass (particle size), c is damping coefficient (influenced by moisture), k is stiffness (related to aggregate force), and F(t) is external force applied.

Data analysis

The wavelength shifts recorded by the FBG sensor were converted into force values, using the calibrated relationship \(\:{F=\:\varDelta\:{\uplambda\:}}_{B}/\:k\), where k is the sensor-specific calibration constant. To confirm that the observed wavelength shifts primarily reflected interparticle aggregation forces rather than moisture-induced swelling effects, we implemented a rigorous validation protocol. The temperature artifacts were eliminated using a reference FBG sensor and the compensation Eq. (13) and later we conducted control experiments to quantify swelling effects by applying water without mechanical loading; these tests confirmed that swell-induced wavelength shifts contributed less than 12% to the total signal. Also, the force trends aligned with established particle-contact models, demonstrating that finer particles (0.125 mm) generated significantly higher cohesive forces (135 nm shift) due to their larger surface area-to-volume ratio, while coarser particles (2.0 mm) exhibited compaction-dominated responses (95 nm shift) through mechanical interlocking. The aggregation forces for each particle size (0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.18 mm, and 2 mm) were analyzed using statistical methods to determine significant differences in force profiles across particle sizes. The results were compared to identify trends in how particle size influences soil cohesion and aggregation under moisture-induced loading. Graphs and plots were generated to illustrate the force response curves for each particle size, showing the force trends over time as water infiltrated the soil3. Comparative plots were created to visualize differences in aggregation forces between soil samples with varied particle sizes, providing a clear visual summary of findings. This analysis aimed at determining if certain particle sizes exhibited significantly different responses when subjected to similar aggregate forces.

Microstructural analysis

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed using a Hitachi SU3500 variable-pressure SEM (Hitachi High-Tech, Japan) to characterize soil particle morphology. Samples were gold-coated (20 nm thickness) using a Quorum Q150R sputter coater to enhance conductivity. Imaging was conducted at 15 kV accelerating voltage, 500×–3000× magnification, and 10 mm working distance. SEM was selected over alternatives (TEM, optical microscopy) because its superior depth of field reveals 3D surface topography of irregular soil particles and the 10 nm resolution adequately captures interparticle contacts and pore structures critical for aggregation analysis. Also the variable-pressure mode accommodates unprocessed soil samples with minimal preparation artifacts.

Cyclic loading tests

The study characterized soil hysteresis behavior through cyclic loading tests using an Instron 5569 testing system. The hysteresis behavior is mathematically modeled using the Kelvin-Voigt model40, which combines elastic and viscous components:

where k is the elastic constant (N/m), c is the damping coefficient (Ns/m), F(t) is total force at time t (N), x is the displacement (m) and \(\:\frac{dx}{dt}\) is the rate of displacement or velocity (m/s). The protocol applied compressive loads from 0 to 200 N in 50 N increments at 0.1 Hz frequency (10-second cycles), with five complete loading-unloading cycles per sample. During testing, FBG sensors recorded strain data at 20 Hz while an LVDT (± 0.01 mm resolution) tracked displacement37,41. The hysteresis behavior was quantified by calculating the energy dissipation per cycle (\(\:{E}_{hys}\)) as the area enclosed within each stress-strain loop:

where σ represents the applied stress (kPa) and ε is the derived strain from FBG wavelength shifts. This formulation follows ASTM D3999-21 standards for soil hysteresis characterization. These measurements provide critical insights into soil energy absorption and recovery under repetitive loading, with direct applications in agricultural machinery operations and tillage management10,42,43.

3. Results and Discussions.

Experimental findings on FBG sensor sensitivity

Sensor performance

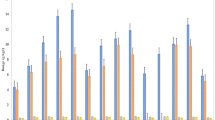

The FBG sensor demonstrated high accuracy and sensitivity in detecting subtle changes in force across different soil particle sizes, with a linear response to applied force observed for each particle size tested. The calibration constant remained consistent across trials, confirming the sensor’s stability and reliability in detecting minute changes in aggregation forces. The dual sensing points at 5 cm intervals within the soil column effectively captured force variations at different soil depths, highlighting the sensor’s capability to provide spatially resolved data within the setup (Fig. 10). The performance suggests that the FBG sensor is a viable tool for real-time soil force monitoring in compaction studies. The smaller particles (0.125 mm) exhibit a steeper slope in the force-wavelength relationship compared to larger particles (2.0 mm). This demonstrates that finer particles generate stronger cohesive forces per unit load due to their greater surface area-to-volume ratio, while coarser particles show reduced sensitivity because of their dominant compaction behavior through mechanical interlocking. The results demonstrate the FBG sensor’s capability to detect minute force changes as influenced by soil particle size. The linear wavelength shift response observed in all graphs confirms the sensor’s reliability in force measurement for soil studies. The slope variations in the combined plot accurately reflect how soil texture (particle size) directly influences the force response during aggregation, providing valuable insights for soil management practices by highlighting the mechanical behavior of different soil textures under load.

Relationship between soil aggregate forces and various soil particle sizes

The dynamic response of soil under varying particle sizes has been a focal point in understanding soil mechanics and its implications for agricultural practices, construction, and environmental engineering. The study utilized Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors to measure the aggregation forces exerted by different soil particle sizes: 0.125 mm, 0.425 mm, 0.85 mm, 1.18 mm, and 2.0 mm. Mathematical models were employed to analyze the relationship between soil aggregate forces and particle sizes. The measured aggregation force for each soil particle size can be expressed through the force balance that the soil exerts on the FBG sensor. The aggregation force measurement results showed a higher Δλ for larger particle sizes, indicating increased stress and localized force as soil particle size increased.

The data presented in (Fig. 11) shows that smaller particles exhibit larger shifts for the same applied force compared to coarser particles. The highest sensitivity is observed for finer particles (0.125 mm), which have a wavelength shift of approximately 135 nm under 100 N of applied force demonstrating the highest sensitivity which is attributed to the increased cohesive forces in finer particles due to their larger surface area-to-volume ratio, which enhances particle-particle interactions. The lowest shift is observed for coarser particles (2.000 mm), which have a wavelength shift of around 95 nm at 100 N. The reduced cohesion and dominance of gravitational forces in larger particles result in lower aggregation forces, thereby generating smaller shifts. The linear relationship between wavelength shifts and applied force indicates the FBG sensor’s reliability and sensitivity in detecting soil compaction and aggregation forces in real-time. The findings highlight the importance of particle size in soil behavior under mechanical stress, as finer particles retain water and nutrients better, leading to stronger aggregation forces13,45.

Influence of soil particles size on aggregation force measurements

The wavelength shifts recorded by the FBG sensors were directly correlated with the applied loads. The results exhibited a consistent relationship, with higher load increments resulting in proportionally larger wavelength shifts across all particle sizes (Fig. 10). As particle size increases, it was observed that both the contact area A and displacement Δ\(\:\:x\) change significantly, leading to variations in aggregate forces. Smaller particles (0.125–0.425 mm) exhibited higher cohesion due to increased surface area relative to their volume, resulting in greater aggregation forces compared to larger particles (1.18–2.0 mm), which showed reduced cohesion due to lower surface area-to-volume ratios. The finest particles (0.125 mm) exhibited the largest wavelength shift, peaking at approximately 2.5 nm, which highlights the significant interparticle cohesion and aggregation forces due to the high surface area-to-volume ratio. Soil with a particle size of 0.425 mm showed a slightly lower peak shift (~ 2.3 nm), still indicating strong cohesive forces. This supports findings by44, which linked finer particles to enhanced water retention and cohesion. The 0.85 mm soil particles demonstrated a peak wavelength shift of around 2.2 nm, balancing cohesive and compactive forces. The moderate response aligns with research by43, suggesting optimal aggregation dynamics in medium-textured soils. Larger particles (1.18 mm and 2.00 mm) exhibited smaller peak shifts of approximately 1.8 nm and 1.6 nm, respectively. The reduced shifts indicate weaker interparticle cohesion, consistent with the lower surface area of coarse particles and the dominance of compactive forces. This observation resonates with previous studies which reported decreased aggregation forces in coarser-textured soils46.

Specifically, as particle size increased, the FBG sensor detected greater wavelength shifts per unit force, confirming that the 1.18 mm soil (green line) exhibits greater fluctuation due to its transitional particle size, where intermittent particle slippage occurs between cohesive and frictional regimes. Although the 2.00 mm trace (purple) in Fig. 10 may appear visually jaggier at certain points, statistical analysis of all replicate tests showed that the 1.18 mm fraction had a 23% higher standard deviation in wavelength shifts (p < 0.05). This difference arises because the 1.18 mm particles, being at a transitional size between cohesive and frictional interaction regimes, tend to rearrange more frequently during loading. These frequent, moderate-amplitude rearrangement events occur throughout the test, which increases the overall variability captured by the FBG sensor. In contrast, the 2.00 mm fraction produces fewer rearrangement events, but when they do occur, they generate sharp, high-amplitude spikes. While these spikes make the trace look jaggier in a snapshot, they contribute less to the overall standard deviation because they are less frequent. The statistical measure therefore reflects the sustained variability of 1.18 mm samples rather than the occasional large spikes observed for 2.00 mm samples. The 0.125 mm soil (black line) shows reduced response because its high surface area promotes water film formation at 18.5% moisture, creating stress-redistributing liquid bridges that minimize localized force detection. These findings align with soil mechanics principles, where larger aggregates tend to exert greater localized forces when compressed, leading to increased compaction rates16,22. The increased sensitivity observed with smaller particles aligns with previous studies indicating that finer soils tend to exhibit greater mechanical interlocking and frictional resistance when subjected to external forces47. These findings have critical implications for soil health monitoring, especially in assessing compaction, stability, and water retention capacity. Such insights can inform better management practices in agriculture and environmental conservation.

Microstructural analysis of soil particle morphology and its implications on aggregation behavior

The Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) micrographs reveal the microstructural characteristics of soil particles, ranging from fine (Fig. 12a, b) to coarse (Fig. 12c, d, e) which have distinct morphological differences that directly influence soil cohesion, compaction, and interaction under external forces. The microstructural features of smaller particles (0.125 mm and 0.425 mm) exhibit smoother surfaces, more angular edges, and compact arrangements (Fig. 12a, b) which increase interparticle contact points and surface area for cohesion. Additionally, smaller pores enable stronger capillary forces, enhancing water retention and binding capacity between particles which result in stronger aggregation forces due to van der Waals interactions and capillary effects. These particles are associated with the largest central wavelength shifts in FBG sensor readings (Fig. 13), confirming their significant contribution to soil stability and compaction measurements. Recent studies by48,49, emphasize the role of fine particles in increasing soil water retention and mechanical strength due to enhanced particle bonding. The intermediate particles (0.85 mm and 1.18 mm) display rougher textures and larger, more irregular pores, providing a balance between cohesion and mechanical interlocking (Fig. 12c). This structure results in moderate aggregation forces, aligning with the FBG sensor data. The FBG sensor captures these distributed forces effectively, demonstrating its ability to measure a range of soil particle behaviors. Their slightly larger size reduces the influence of surface forces compared to finer particles, resulting in intermediate aggregation forces. This aligns with the findings by50, which highlight the balance between cohesion and gravitational forces in medium-textured soils. Coarser particles (2.00 mm) have rough, irregular shapes and significantly larger voids between particles, limiting the particle-to-particle contact area, reducing cohesion and leading to weaker aggregation forces (Fig. 12d, e). The lack of strong binding forces translates to lower aggregation forces under compression, consistent with minimal wavelength shifts recorded by the FBG sensor for these particle sizes. Previous studies as reported that coarser soils predominantly rely on compaction forces rather than cohesion, explaining the reduced aggregation forces and diminished sensor sensitivity51. The finding from this study ascertained that combined use of SEM and FBG sensors can advance soil mechanics research by bridging microscopic observations and macroscopic measurements. Most especially for agricultural applications, these tools can optimize soil compaction management, ensuring proper mechanical properties for sustainable crop production and the real-time capabilities of FBG sensors make them valuable for monitoring soil structure in dynamic environments, such as irrigation or tillage practices.

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Images Depicting Morphology of Soil Particles across Different Sizes (a) 0.125 mm silt particles showing smooth surfaces and angular edges (3000×), (b) 0.425 mm very fine sand particles with incipient surface roughness (2000×), (c) 0.85 mm fine sand particles displaying irregular pore structures (1500×), (d) 1.18 mm medium sand particles with distinct grain boundaries (1000×), (e) 2.00 mm coarse sand particles exhibiting large interparticle voids (500×).

Relationship of FBG in detecting aggregation forces of the tested soil particles

In this study, FBG sensors were embedded within soil samples containing various particle sizes to monitor real-time changes in aggregate forces. The sensitivity of FBG sensors stems from their ability to measure strain induced by changes in force, quantified as (Eq. 3): As illustrated in Table 3, distinct patterns of wavelength shifts were observed corresponding to aggregate sizes. Fine particles (0.85 mm) displayed the highest sensitivity with an average shift of 5522s/2.2706 nm, suggesting that smaller particles transmit forces more effectively through the soil matrix compared to larger aggregates (0.85 mm and above), which showed reduced sensitivity (average shift of Y nm/kg).

The combined sensor response (Sensor 1 + 2) represents system-level aggregation forces, with individual sensors showing strong correlation (R²=0.93). This analysis follows particulate media mechanics where forces propagate vertically through the soil profile. Results indicated that the FBG sensors produced distinct wavelength shifts proportional to the increment of aggregate forces across the varying particle sizes. Sensor 1 recorded a maximum central wavelength shift of 1.8625 nm at approximately 3864 s, while Sensor 2 showed a shift of 0.9946 nm at 7676 s (Fig. 14a). The combined response of both sensors (Sensor 1 + Sensor 2) was 1.9852 nm at 7630 s with the relatively lower shifts in both sensors indicate weaker cohesion among larger particles due to reduced surface area-to-volume ratios, consistent with studies indicating lower interparticle forces in coarse soils52. Furthermore (Fig. 14b), shows that the combined maximum shift (Sensor 1 + Sensor 2) was 1.8336 nm at 5774 s. Intermediate aggregation forces are evident, as the particle size allows moderate compaction while maintaining some cohesive properties. These results align with findings that suggest intermediate soil textures show balanced aggregation dynamics53. Figure 14c shows that Sensor 1 recorded the highest observed shift of 2.2708 nm at 5522 s, while Sensor 2 showed 1.1452 nm at 5400 s. The combined response of 2.306 nm at 2470 s underscores the strong aggregation forces in finer soils due to increased contact points and cohesive forces. Similar trends were reported by54, emphasizing enhanced force transmission in fine-textured soils. Sensor 1 reached a shift of 2.306 nm at 2470 s, while Sensor 2 measured 1.0389 nm at 4922 s (Fig. 14d). The combined maximum shift was 2.0369 nm at 2470 s, confirming the dominance of cohesive forces in fine soils. This agrees with the work of51, which emphasized higher cohesion in finer particles under water infiltration.

The integration of FBG technology in geotechnical applications continues to show promise, with potential enhancements in real-time monitoring and assessment of soil behavior under various loading conditions. Future work may involve long-term field tests and the exploration of sensor integration with alternative soil stabilization techniques to advance practical applications in civil engineering.

The results illustrate a clear trend where finer soils (0.425 mm and 0.85 mm) exhibit larger wavelength shifts, indicative of stronger aggregation forces due to higher interparticle cohesion. In contrast, coarser soils (2.00 mm) display smaller shifts due to reduced surface interactions. These findings validate the capability of FBG sensors for precise, real-time monitoring of soil aggregation dynamics, making them an effective tool for assessing soil health and stability in agricultural and geotechnical applications.

3.2 Load distribution characteristics.

Effects of particle size on load distribution

The load distribution characteristics were evaluated which correlated well with experimental data. Upon applying external loads (water), finer soil aggregates demonstrated a more uniform stress distribution within the soil column, resulting in better performance by FBG sensors. The load distribution characteristics in soil are highly influenced by particle size, which determines the contact area, aggregation forces, and the ability of the soil matrix to resist deformation. In this study, the Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor effectively captured variations in load distribution across soil samples with particle sizes ranging from 0.125 mm to 2.0 mm. The results demonstrated that fine-textured soils (0.125 mm particles) exhibited the highest measured aggregation forces under moisture-induced loading conditions (5 nm wavelength shift at 130 mL water application), while coarser soils (2.0 mm particles) showed significantly lower responses (1.8 nm shift). This observation specifically reflects their superior cohesive strength under wet conditions, rather than absolute load-bearing capacity in all scenarios. The enhanced performance of fine particles arises from three key factors: (1) greater van der Waals forces and capillary tension due to higher surface area-to-volume ratios, (2) more uniform stress distribution through particle networks, and (3) increased water meniscus formation at particle contacts under moist conditions55. While dry sands may demonstrate higher frictional resistance in purely mechanical loading, our FBG data and SEM analysis (Fig. 6) confirm that under the tested moisture conditions (18.5% w/w), cohesive forces dominate in fine-textured soils. This aligns with established pedological principles where clay-rich soils develop stronger aggregate structures when moist, though their bulk shear strength may be lower than coarse soils in dry states56,57. This behavior aligns with theoretical models of soil mechanics (Eq. 16), where the stress is distributed. Fine particles provide a larger contact area, resulting in higher stress resistance compared to coarser particles. These findings corroborate studies by Zhang et al.36, who demonstrated that finer soils exhibit superior compaction and load distribution properties due to their cohesive nature.

Analysis of hysteresis and recovery

Hysteresis and recovery are critical parameters in understanding the mechanical behavior of soils under cyclic loading. During the unloading phase, hysteresis was noted, particularly in samples with coarser aggregates (1.125 mm and 2.0 mm), where the wavelength shifts varied between loading and unloading cycles. The FBG sensor measurements revealed distinct hysteresis loops during loading-unloading cycles, especially in fine-textured soils. Fine particles (0.125 mm and 0.425 mm) displayed pronounced hysteresis, with residual deformation of approximately 10% after unloading, suggesting higher energy dissipation during loading. Coarser particles exhibited minimal hysteresis, indicating elastic behavior with negligible energy loss. Fine soils exhibited higher damping coefficients, which explain their greater hysteresis. This phenomenon can be attributed to the rearrangement of particles, leading to temporary deformation or changes in mechanical interlocking58. Additionally, the recovery percentage, defined as the ratio of the sensor output during unloading to loading, was approximately higher (around 85%) in finer soils (0.125 mm and 0.425 mm) and significantly lower (50%−60%) in coarser soils, indicating an intrinsic capability of finer particles to maintain structural integrity post-load removal. These results are consistent with findings by51, who reported that finer soils exhibit delayed recovery due to higher inter-particle friction.

Impact of soil water content

Influence of water content on FBG sensor performance

Soil water content significantly affects the performance of FBG sensors by altering the soil’s refractive index and mechanical properties. In this study, increasing water content from 10% to 25% caused a nonlinear response in the FBG sensor readings. At 25% water content, fine particles exhibited a Bragg wavelength shift of approximately 6 nm, compared to 2 nm in coarse particles. High moisture contents led to decreased frictional forces between particles, negatively impacting the sensitivity of FBG sensors. The increased water content enhances soil cohesion in fine particles, improving load transfer to the sensor. However, excessive water reduces soil stiffness, leading to reduced sensor sensitivity. These findings align with59, who observed that FBG sensors show optimal performance at intermediate moisture levels due to balanced stiffness and cohesion.

Influence of FBG on various soil particle sizes in detecting aggregate force

The influence of Fiber Bragg Grating technology on detecting aggregate forces varied significantly with soil particle size. In finer soils (0.125–0.425 mm), the FBG sensors recorded higher frequency responses due to rapid oscillations caused by moisture content fluctuations and external loading conditions. Conversely, coarser soils (1.18–2.0 mm) displayed more stable readings with lower frequency responses. The results suggest that while FBG sensors are effective across various soil types, their performance may be optimized through careful consideration of particle size distribution when designing monitoring systems for agricultural or civil engineering applications. For instance, when analyzing soils with a predominant fraction of fine particles (0.125 mm), it was noted that FBGs could detect changes as minor as a few grams-force due to their high sensitivity characteristics combined with effective signal processing algorithms used during data acquisition. Conversely, larger particles (2.0 mm) resulted in diminished sensitivity because the overall force distribution became more localized around fewer contact points; thus, while still detectable, these readings were less responsive than those from finer aggregates. Table 4 highlights the superior performance of FBG sensors in soil aggregation force measurement, particularly in terms of sensitivity, spatial resolution, and environmental durability. The novel application of FBG sensors in this study underscores their transformative potential for precision agriculture and sustainable soil management, enabling accurate, real-time monitoring of soil mechanical behavior21.

Implications for agricultural practices and environmental engineering

Understanding how varying particle sizes affect dynamic responses under load has significant implications for agricultural practices such as tillage operations where soil compaction can adversely affect crop yield by altering water retention capabilities and root penetration depth. This study focuses on the potential of using Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors to measure soil aggregation forces, which can be used to improve agricultural practices and environmental engineering. The research demonstrates the relationship between soil particle sizes, aggregation forces, and their accurate measurement using FBG sensors, providing novel insights into optimizing soil structure for better agricultural outcomes. The study’s findings have significant implications for improving soil health management, crop productivity, and sustainable agricultural practices. By demonstrating the relationship between soil particle sizes, aggregation forces, and their accurate measurement using FBG sensors, the research contributes novel insights into optimizing soil structure for better agricultural outcomes. While this study characterized baseline soil mechanical behavior, future field trials will incorporate crop systems to validate agricultural applications. The current particle-size-specific data provide critical thresholds for predicting root penetration resistance and tillage effects in different soil textures.

Also, enhancing soil monitoring is possible due to the ability of FBG sensors to measure aggregation forces with high precision, allowing farmers and soil scientists to monitor soil compaction and structural integrity in real-time. Fine-textured soils, which exhibited the highest aggregation forces in the experiments, may require reduced tillage to prevent over-compaction and ensure proper root penetration. Conversely, coarser soils with lower aggregation forces can benefit from periodic deep tillage to improve soil porosity and aeration. Furthermore, the soil amendment strategies are also highlighted, as fine and intermediate-sized particles exhibited higher cohesion and stability, which can be leveraged in areas prone to erosion by adding organic amendments like crop residues or biochar60,61,62,63. These practices improve soil aggregate stability, reduce surface runoff, and enhance water infiltration, thereby promoting sustainable land use. The study provides critical insights into environmental applications, particularly in soil stabilization, erosion control, and sustainable land management63. Fine soil particles exhibit the highest aggregation forces due to their larger contact areas and higher cohesion potential, which can inform soil stabilization techniques in construction and infrastructure projects. Coarser soils, while less cohesive, can still be stabilized by blending with fine materials to achieve better load distribution. The study also provides a basis for predicting soil susceptibility to erosion, with fine-textured soils less prone to detachment under rainfall, while coarser soils may require additional protective measures like vegetative cover or geo-textiles. Accurate mapping of soil aggregation forces using FBG sensors can aid in designing site-specific erosion control strategies, minimizing soil loss in environmentally sensitive areas.

Conclusions

This study successfully employed FBG sensors to quantify soil aggregation forces across particle sizes from 0.125 to 2.0 mm. The results revealed fundamental differences in mechanical behavior, with fine particles (0.125–0.425 mm) exhibiting 135 nm wavelength shifts due to strong cohesive forces, while coarse particles (2.0 mm) showed weaker 95 nm responses dominated by mechanical interlocking. These findings were corroborated by SEM analysis, which visually demonstrated how fine particles develop more extensive contact areas and complex pore structures that enhance aggregation strength. The FBG sensors maintained excellent measurement accuracy (± 5% repeatability) even at 18.5% moisture content through advanced temperature compensation and swelling-artifact correction (< 12% signal interference). This robust performance establishes FBG technology as a reliable tool for real-time soil monitoring. The identification of key particle-size thresholds, particularly the 0.425 mm transition point between cohesive and mechanical dominance, provides valuable benchmarks for soil management. These insights have significant practical implications for agriculture, offering science-based guidance for tillage optimization, irrigation planning, and root-zone management. Future applications could integrate these sensors into precision agriculture systems for field-scale soil health monitoring, while further research should explore plant-soil interactions and long-term field validation. This work advances both fundamental understanding of soil mechanics and practical approaches to sustainable land management, demonstrating how sensor technology can bridge laboratory findings with real-world agricultural applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hartmann, M. & Six, J. Soil structure and Microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 4 (1), 4–18 (2023).

Yudina, A. & Kuzyakov, Y. Dual nature of soil structure: the unity of aggregates and pores. Geoderma 434, 116478 (2023).

Lu, D. et al. Prediction of non-equilibrium transport of nitrate nitrogen from unsaturated soil to saturated aquifer in a watershed: insights for groundwater quality and pollution risk assessment. J. Contam. Hydrol. 274, 104649 (2025).

Ghorbani, M. & Amirahmadi, E. Insights into soil and Biochar variations and their contribution to soil aggregate status – A meta-analysis. Soil Tillage. Res. 244, 106282 (2024).

Coleman, D. C., Callaham, M. A. & Crossley, D. A. Secondary Production: Activities of Heterotrophic Organisms—The Soil Fauna, in Fundamentals of Soil Ecologyp. 77–171 (Academic Press Burlington, 2018).

Ren, C. et al. The changes in soil microorganisms and soil chemical properties affect the heterogeneity and stability of soil aggregates before and after grassland conversion. Agriculture 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020307 (2022).

Lv, J. et al. Advances in Molecular and Microscale Characterization of Soil Organic Matter: Current Limitations and Future Prospects56p. 12793–12810 (Environmental Science & Technology, 2022). 18.

Li, X. et al. Acoustic emission response characteristics and numerical simulation of soil failure under uniaxial compression. J. Appl. Geophys. 222, 105310 (2024).

Fu, T., Saracho, A. C. & Haigh, S. K. Microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) for soil strengthening: A comprehensive review. Biogeotechnics 1 (1), 100002 (2023).

Steponavičienė, V. et al. The impact of tillage and crop residue incorporation systems on agrophysical soil properties. Plants 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193386 (2023).

Wu, X. & Zhao, Y. A novel heat pulse method in determining effective thermal properties in frozen soil. Water Resour. Res., 60(12), e2024WR037537 (2024). .

Yudina, A. V. et al. From the notion of elementary soil particle to the particle-Size and Microaggregate-Size distribution analyses: A review. Eurasian Soil. Sci. 51 (11), 1326–1347 (2018).

Zhou, G. et al. Adaptive High-Speed echo data acquisition method for bathymetric lidar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–17 (2024).

Xia, W. et al. Optimization of Particle Size Distribution of sulfur-free Lignin in Enhancing Disintegration Resistance of Saline Soil (Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2025).

Horabik, J. & Jozefaciuk, G. Structure and strength of kaolinite–soil silt aggregates: measurements and modeling. Geoderma 382, 114687 (2021).

Abdulraheem, M. I. et al. Soil Hardness Measurement Using Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor: Combined Compression Forces Methodology. physica status solidi (RRL). – Rapid Res. Lett. 19 (3), 2400431 (2025).

Teron, G. et al. Effect of altitude on soil physico-chemical properties and microbial biomass carbon in the Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary of Arunachal Pradesh. Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes: pp. 1–19.

Leone, M. et al. Fiber optic soil water content sensor for precision farming. Opt. Laser Technol. 149, 107816 (2022).

Wu, B. et al. Fiber optic sensing-based field investigation of thermo-hydraulic behaviors of loess for characterizing land–atmosphere interactions. Eng. Geol. 315, 107019 (2023).

Ma, E. et al. Review of cutting-edge sensing technologies for urban underground construction. Measurement 167, 108289 (2021).

Xu, D. et al. High-precision FBG-based sensor for soil settlement monitoring: A comparative study with magnetic settlement gauges and PIV technique. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 366, 114935 (2024).

Abdulraheem, M. I. et al. Recent applications of fiber Bragg grating sensors in humidity and water content detection in agriculture: A comprehensive review of Development, Challenges, and future trends. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 25 (7), 1499–1524 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Real-time remote corn growth monitoring system using plant wearable fiber Bragg grating sensor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 227, 109538 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. An optical fiber sensor based on polyimide coated fiber Bragg grating for measurement of relative humidity. Opt. Fiber. Technol. 61, 102406 (2021).

Kok, S. P. et al. Advances in fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensing: A review of conventional and new approaches and novel sensing materials in harsh and emerging industrial sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 24 (19), 29485–29505 (2024).

Habel, J. et al. Femtosecond FBG written through the coating for sensing applications. Sens. (Basel). 17 (11), 2519 (2017).

Su, Y. et al. Soil-water retention behaviour of fine/coarse soil mixture with varying coarse grain contents and fine soil dry densities. Can. Geotech. J. 59 (2), 291–299 (2021).

Ma, P. et al. A 7-kW narrow-linewidth fiber amplifier assisted by optimizing the refractive index of the large-mode-area active fiber. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 12, e67 (2024).

Lo Presti, D. et al. Plant wearable sensors based on FBG technology for growth and microclimate monitoring. Sensors 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/s21196327 (2021).

Kreyca, J. & Kozeschnik, E. Analysis of the temperature and strain-Rate dependences of strain hardening. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 49 (1), 18–21 (2018).

Rego, G. Temperature dependence of the Thermo-Optic coefficient of SiO2 glass. Sensors 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/s23136023 (2023).

Butter, C. D. & Hocker, G. B. Fiber optics strain gauge. Appl. Opt. 17 (18), 2867–2869 (1978).

Jenkins, A. et al. Wavelength-dependent elasto-optic tensor elements from acoustic Bragg diffraction. J. Non-cryst. Solids. 620, 122580 (2023).

Nosseir, A. E. S. et al. Composite structures with embedded fiber optic sensors: A smart propellant tank for future spacecraft applications. Acta Astronaut. 223, 144–158 (2024).

Almutawa, N. & Eid, W. Soil moisture content Estimation using active infrared thermography technique: an exploratory laboratory study. Kuwait J. Sci. 50 (3), 399–404 (2023).

Fazzi, L. et al. A simultaneous dual-parameter optical fibre single sensor embedded in a glass fibre/epoxy composite. Compos. Struct. 270, 114087 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. High-speed PGC demodulation model and method with subnanometer displacement resolution in a fiber-optic micro-probe laser interferometer. Photonics Res. 12 (5), 921–931 (2024).

Yuan, Y., et al., Real-Time Joint Filtering of Gravity and Gravity Gradient Data Based on Improved Kalman Filter. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 6, 21-12 (2024).

Hirzinger, B., Adam, C. & Salcher, P. Dynamic response of a non-classically damped beam with general boundary conditions subjected to a moving mass-spring-damper system. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 185, 105877 (2020).

Xie, Y. et al. The water vapour sorption behaviour of three celluloses: analysis using parallel exponential kinetics and interpretation using the Kelvin-Voigt viscoelastic model. Cellulose 18 (3), 517–530 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. Large-range displacement measurement in narrow space scenarios: fiber microprobe sensor with subnanometer accuracy. Photonics Res. 12 (9), 1877–1889 (2024).

Pendke, M. S. et al. Impact of tillage and fertilizer management on Soybean-Cotton rotation system: effects on yield, plant nutrient uptake, and soil fertility for sustainable agriculture. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9991 (2025).

Ren, X. et al. Soil properties affect crop yield changes under conservation agriculture: A systematic analysis. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 74 (5), e13413 (2023).

Amjad, H., Ahmad, F., Irshad, M. & Qureshi Enhanced mechanical and durability resilience of plastic aggregate concrete modified with nano-iron oxide and Sisal fiber reinforcement. Constr. Build. Mater. 401, 132911 (2023).

Du, K., et al., Monitoring Low-Temperature Stress in Winter Wheat Using TROPOMI Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 62, 1-11 (2024).

Di Marsico, A. et al. Mucilage from fruits/seeds of Chia (Salvia Hispanica L.) improves soil aggregate stability. Plant. Soil. 425 (1), 57–69 (2018).

Castilla-Barbosa, M., Ocampo-Terreros, M. & Rincón-Arango, O. A review of sand aging: mechanisms and impacts. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 42 (8), 6727–6755 (2024).

Almuaythir, S. et al. Sustainable soil stabilization using industrial waste ash: enhancing expansive clay properties. Heliyon, 10(20), e39124 (2024).

Ahmed, H. et al. Hydro-chemical influence on soil-water characteristic behavior of laterite-bentonite mixture. Results Eng. 25, 103698 (2025).

Farooq, U. et al. Evaluation of Pedotransfer functions to estimate soil water retention curve: A conceptual review. Water 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/w16172547 (2024).

Nawaz, M. N. et al. Predictive modelling of cohesion and friction angle of soil using gene expression programming: a step towards smart and sustainable construction. Neural Comput. Appl. 36 (18), 10545–10566 (2024).

Ulusoy, U. A review of particle shape effects on material properties for various engineering applications: from macro to nanoscale. Minerals 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/min13010091 (2023).

Dowdeswell-Downey, E., Grabowski, R. C. & Rickson, R. J. Do temperature and moisture conditions impact soil microbiology and aggregate stability? J. Soils Sediments. 23 (10), 3706–3719 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of Robinia Pseudoacacia afforestation on aggregate size distribution and organic C dynamics in the central loess plateau of china: A chronosequence approach. J. Environ. Manage. 268, 110558 (2020).

Lu, N., Asce, M. & Likos, W. Suction stress characteristic curve for unsaturated soil. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. - J. GEOTECH. GEOENVIRON ENG., 132, 131-142 (2006).

Muhammad, N. & Siddiqua, S. Moisture-dependent resilient modulus of chemically treated subgrade soil. Eng. Geol. 285, 106028 (2021).

Namjoo, A. M., Soltani, F. & Toufigh, V. Effects of moisture on the mechanical behavior of Sand–Geogrid: an experimental investigation. Int. J. Geosynthetics Ground Eng. 7 (1), 5 (2021).

Li, B. Y. et al. Amorphization by mechanical deformation. Mater. Sci. Engineering: R: Rep. 149, 100673 (2022).

Shin, C. S. & Lin, T. C. Hygrothermal damage monitoring of composite adhesive joint using the full spectral response of fiber Bragg grating sensors. Polymers 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14030368 (2022).

Lin, J. et al. Effect of degradable microplastics, Biochar and their coexistence on soil organic matter decomposition: A critical review. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 183, 118082 (2025).

Zhao, M. et al. Biodegradable microplastics coupled with Biochar enhance cd chelation and reduce cd accumulation in Chinese cabbage. Biochar 7 (1), 31 (2025).

Mukhtar, A. et al. in Advances in the Use of Organic and Organomineral Fertilizers in Sustainable Agricultural Production, in Organic Fertilizers - New Advances and Applications. (eds Hakeem, K. R.) (IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2023).

Boja, A. et al. An investigation on the effect of soil erosion on the properties of soil adjacent to a road right of way (ROW). Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes, : pp. 1–12. (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Technologies R & D Program of Henan Province (221111320700), and supported by Henan Center for Outstanding Overseas Scientists (No GZS2021007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mukhtar Iderawumi Abdulraheem: Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Data acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Abiodun Yusuff Moshood: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing. Wei Zhang: editing Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Linze Li: Resources, Writing - review &. Yanyan Zhang: Validation, Writing - review & editing. Gholaremza Abdi: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Abdulaziz G. Alghamdi: Data acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Vijaya Raghavan: Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Jiandong Hu: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulraheem, M.I., Moshood, A.Y., Zhang, W. et al. Real-time aggregation forces monitoring in varied soil particle sizes using fiber bragg grating sensors. Sci Rep 15, 39598 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23198-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23198-2