Abstract

Anthropogenic activities have led to severe environmental degradation, posing a significant threat to global sustainability. Among these pollutants, synthetic dyes are of particular concern due to their contribution to water contamination and detrimental effects on ecosystems. Herein, we present an eco-friendly approach to remove toxic dyes from wastewater using silver nanoparticle-decorated chitosan-coated cotton fabric (Ag/Chi-CF) as a heterogeneous nano-catalyst. A 1 wt% Chi solution was applied to cotton fabric to enhance surface functionality and improve metal ion uptake capacity. The functionalized fabric was then treated with silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solutions at concentrations of 100, 200, and 300 μg/mL. Next, the subsequent reduction with 0.1 M NaBH4 hydrate facilitates the in situ formation of silver nanoparticles, which is confirmed by a visible color change. The untreated cotton fabric (CF), chitosan-coated cotton (Chi-CF), and Ag/Chi-CF were characterized by SEM, XRD, EDX, and FTIR for their surface morphology, crystal structure, elemental analysis, and functional groups, respectively. Catalytic degradation studies were conducted with UV–Vis spectroscopy using Congo red dye as a model pollutant. The Ag3/Chi-CF nano-catalyst demonstrated excellent catalytic performance, achieving approximately 90% degradation of 50 ppm dye within 20 min (k_obs = 0.1 min⁻1), following a second-order kinetic model, while showing a poor fit to zero-order and first-order models. The reusability of the Ag3/Chi-CF catalyst was demonstrated through three cycles, with minimal loss in performance to approximately 77%, highlighting its potential for sustainable wastewater treatment applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental pollution has become a primary global concern due to the excessive release of organic and inorganic contaminants, as well as pathogenic microorganisms1. Anthropogenic activities, including intensive agricultural practices, domestic waste discharge, and unsustainable industrial operations, are the main contributors to the introduction of these pollutants into the environment2. In particular, the rapid proliferation of high-emission industries such as textiles, tanning, food and beverages, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals has led to the accumulation of toxic, persistent, and bio-refractory chemicals in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems3,4. Concurrently, the growing global population and the overexploitation of natural resources have further strained efforts toward environmental sustainability5,6.

Among the various forms of pollution, water contamination remains one of the most pressing challenges, with synthetic dyes in industrial effluents posing significant risks to both ecosystems and human health7,8. Industries such as textile manufacturing, leather processing, paper production, and dye synthesis discharge large volumes of dye-laden wastewater into aquatic environments9. Every year, more than 70 million tons of synthetic dyes are produced globally, with more than 10,000 tons of these dyes consumed by the textile industry. Among these, azo dyes account for nearly 50% of all dyes used worldwide10. According to an estimate, about 15–50% of azo dyes used in the textile industry are not bonded to fibers and fabrics, resulting in their discharge into wastewater due to inefficient textile dyeing procedures11,12,13.

Synthetic dyes are generally classified into three main types: anionic (including direct, acid, and reactive dyes), cationic (e.g., basic dyes), and nonionic (e.g., disperse dyes)9. Among these, Congo red (CR), a water-soluble anionic diazo dye, is widely used in various industrial applications such as textiles, paper, printing, and plastics. However, its structural stability, high solubility, and resistance to biodegradation hinder effective removal via conventional wastewater treatment techniques14. Furthermore, CR is known to exhibit carcinogenic and mutagenic effects, necessitating the development of more effective and environmentally sustainable removal methods15.

Although conventional dye removal technologies such as adsorption, coagulation-flocculation, membrane filtration, and advanced oxidation processes have been widely adopted, they often suffer from several limitations. These include high operational costs, secondary pollutant generation, incomplete degradation of dyes, and complex operational procedures. In contrast, catalytic reduction methods using metal nanoparticles have shown significant promise due to their ability to achieve complete mineralization of dyes and facilitate catalyst reusability16.

Among catalytic materials, metallic nanoparticles, particularly silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), have attracted considerable attention for their remarkable catalytic efficiency, which is attributed to their high surface area-to-volume ratio17,18. For instance, Bharathi et al. synthesized AgNPs using Merremia quinquefolia leaf extract, and the as-synthesized NPs were subsequently used for the inhibition of bacteria (Inhibitory zone 14 ± 0.23 mm), antioxidant activity (IC50 values, DPPH = 145.7 μg/mL and ABTS = 112.09 μg/mL), and photocatalytic degradation of dye (98% in 240 min)19. In another report, Segun et al. biosynthesized AgNPs using Peltophorum pterocarpum leaf extract at 80 °C. The as-synthesized NPs exhibited good catalytic activity using NaBH4 as a reducing agent and enhanced antibacterial activity against selected pathogens20. Furthermore, AgNPs were also synthesized by Baraa et al. using Saussurea costus extract, and the activity was evaluated in the degradation of dyes and bacterial decontamination21.

However, their practical deployment of AgNPs is often hindered by challenges such as particle agglomeration and difficulties in recovering the nanoparticles post-treatment22. To mitigate these limitations, recent research has focused on the immobilization of nanoparticles onto solid support to enhance stability and reusability23,24,25. For example, Debnath et al. generated in situ AgNPs in MBA crosslinked sodium alginate grafted poly (acrylonitrile-co-sodium acrylate-co-acrylic acid) for the adsorption cum photo-degradation of MB with 98% efficiency in 80 min26. Additionally, in another report, Azhar et al. degraded RB, MO, Bb, MB, and CR dyes using poly(chitosan-N-isopropylmethacrylamide-acrylic acid) microgel particles embedded with AgNPs27.

Chitosan, a naturally derived biopolymer obtained via deacetylation of chitin, possesses unique properties such as film-forming capability, biocompatibility, and functional groups that facilitate metal ion binding28,29,30. When integrated with cellulose, a polysaccharide abundantly found in cotton fibers, the resulting Chi-cellulose composite exhibits improved mechanical properties, increased surface area, and enhanced support characteristics suitable for nanoparticle immobilization31,32.

In this study, a Chi-CF was synthesized and subsequently impregnated with AgNPs through a chemical reduction process using NaBH4 as a reducing agent. The resulting Ag/Chi-CF was extensively characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR). The synthesized Ag/Chi-CF nano catalyst was then utilized for the catalytic degradation of CR dye in water. A systematic study was conducted to assess the impact of different dye concentrations and catalyst amounts on degradation efficiency, highlighting the potential of Ag/Chi-CF as an effective and environmentally friendly nano-catalyst for dye removal in wastewater treatment.

Experimental

Materials

Congo red (C3₂ H₂₂N₆Na₂O₆S₂), with ≥ 85% dye content certified by the Biological Stain Commission, was used in this study. Congo red was purchased from British Drug House Ltd. Poole, England. Acetic acid was purchased from Merck, Germany. Chitosan, with medium molecular weight and a degree of deacetylation between 80 and 95%, was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., China. Cotton cloth was purchased from a local market and manufactured by a local textile industry. According to the manufacturer, the cotton cloth fibers consist of 91% cellulose, 8% hemicellulose, 1% wax, and trace amounts of dye. Sodium borohydride was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany, and silver nitrate was purchased from Panreac Quimica S.A., Barcelona, Spain. All chemicals were used without further purification. All the solutions were prepared using deionized water.

Preparation of cotton cloth surface

The surface of cotton fabrics (CF) was modified using chitosan (Chi). An aqueous solution of Chi was prepared with a concentration of 1% wt. Chi powder was added to a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution prepared with deionized water. The solution was stirred overnight to produce a clear Chi solution. Next, a 2 × 2 cm2 strip of CF was dipped in the Chi solution and left for 4 h to ensure complete coating with Chi. Finally, the Chi-coated CF was dried in an oven at 50 °C for further analysis.

Synthesis of Ag/Chi-CF

A silver nitrate solution was prepared at three different concentrations: 100 ppm, 200 ppm, and 300 ppm. Chi-CF strips were immersed in these solutions, allowing Ag⁺ ions to be absorbed via interactions with the –OH and –NH functional groups on the Chi polymer chain. After an appropriate deposition period, the Chi-CF strips were removed and dried overnight at 50 °C. Next, the dried Ag/Chi-CF strips were immersed in a 0.1 M sodium borohydride solution to convert the adsorbed ions into nanoparticles. The resulting strips were labeled as Ag1/Chi-CF, Ag2/Chi-CF, and Ag3/Chi-CF, corresponding to 100 ppm, 200 ppm, and 300 ppm silver concentrations, respectively. A control strip without silver nanoparticles, referred to as Chi-CF, was also prepared for comparison.

Catalytic experiment

The catalytic performance of Ag/Chi-CF was assessed based on its ability to degrade CR dye. In a typical experiment, 2 mL of a 50 ppm CR solution was added to a quartz cuvette, and its UV–visible spectrum was recorded using an Ultraviolet–Visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer. Then, 2 mL of CR solution was mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 N sodium borohydride to initiate the reduction reaction. A 2 × 2 cm2 piece of Ag/Chi-CF catalyst was subsequently added to the cuvette, ensuring it was positioned to avoid obstructing the UV–Vis radiation. Absorbance measurements were taken at regular intervals to monitor CR dye degradation. Upon complete degradation, the Ag/Chi-CF catalyst was removed, oven-dried, and reused in three consecutive catalytic cycles (n = 3) to assess its recyclability and stability. All experiments were performed sequentially to minimize oxidation of AgNPs. Dye degradation kinetics were analysed using zero-order, first-order, and second-order models.

The Zero-order kinetic model is represented by Eqs. (1)–(2).

where C₀ and Cₜ are the initial and time-dependent dye concentrations, respectively, k is the zero-order rate constant, and the plot is obtained by Cₜ vs. time. The first-order kinetic model is shown in Eqs. (3)–(5).

where k is the first-order rate constant, and the plot is obtained by ln(C₀/Cₜ) vs. time. The second-order kinetic model is expressed by Eqs. (6)–(7):

where k is the second-order rate constant, and the plot is obtained by 1/Cₜ–1/C₀ vs. time.

Characterization

Morphological characteristics of the untreated CF, Chi-CF, and Ag/Chi-CF were investigated using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM; JSM5910, JEOL, Japan). Particle sizes were estimated using the ImageJ software. For elemental analysis, Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX), integrated with SEM (JSM-5910, Oxford Instruments, U.K.), was used to confirm the presence of AgNPs on the surface of Chi-CF. The crystallinity and phase composition of the samples were analyzed using X-ray Diffraction (XRD; JEOL JDX-3532, Japan), operated at 40 mA, 40 kV, and a scan range of 5°–80°, with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Surface functional groups were examined using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with a scan rate of 10 scans per second over a range of 4000–600 cm⁻1. UV–Vis spectroscopy, with a measurement range of 200–800 nm, was used to evaluate the absorbance properties of the samples.

Results and discussions

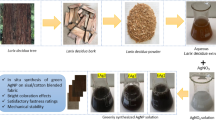

Figure 1 shows the main steps involved in the preparation of Ag/Chi-CF catalytic strips. Coating CF with Chi produced Chi-CF, which exhibited enhanced mechanical strength but became slightly more brittle compared to pristine CF, due to the interconnection of individual cellulose microfibers by the Chi polymer. A distinct mustard–golden color appeared when Ag/Chi-CF strips were immersed in aqueous NaBH₄ solution, confirming the uptake of Ag⁺ ions by –NH₂ and –OH groups within the Chi layers and their subsequent reduction to AgNPs. The color change occurred within a few seconds, indicating that the reaction between NaBH₄ and metal ions was rapid. The chemical reaction involved in this process is presented in Eq. 8.

(a) Schematic representation of the synthesis of AgNPs-loaded catalytic strips (created using BioRender software under license). (b) Digital images of hexane-washed CF, Chi-CF (showing a color change to light grey), and AgNPs-loaded Chi-CF (showing a color change to mustard), demonstrating the successful adsorption of Ag+ and its reduction to AgNPs upon treatment with NaBH4.

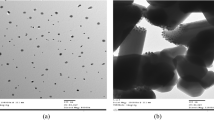

SEM images of the bare CF, Chi-CF, and Ag/Chi-CF are presented in Fig. 2. The surface of the untreated cotton fabric (Fig. 2a) appeared to be rough, with small aggregations likely arising from fiber entanglement. Furthermore, it was observed that upon modifying CF with Chi, the original morphology of CF remains largely unchanged, and the coating appeared uniform across the surface, with no evidence of microphase separation, indicating good compatibility between the cellulose matrix and Chi (Fig. 2b). These observations suggest that Chi was absorbed as a thin layer around the CF microfibers, facilitated by hydrogen bonding between –OH groups of cellulose and −NH2 groups of Chi.

SEM images showing the surface morphology of (a) uncoated cotton fabric (CF), (b) Chi-CF), (c) AgNP-loaded Chi-CF (Ag3/Chi-CF) at lower magnification, and (d) Ag3/Chi-CF at higher magnification, clearly displaying embedded AgNPs. (e) Representative EDX spectrum of the Ag3/Chi-CF sample deposited on a silicon water. The signals for Si and O in (e) originate from standard SiO₂, while C and O are attributed to CaCO₃ and Na-albite standards, respectively. The inset table in (e) shows the elemental composition ratios.

In the case of Ag/Chi-CF, notable morphological changes were observed at the micrometer scale. Figure 2d shows numerous small spots on the microfibers, indicating that AgNPs (129 ± 8 nm; see Fig. 3) were successfully formed on the surface of Chi-CF, as further confirmed by XRD analysis (Fig. 4a). The successful synthesis of AgNPs on the Chi layer over CF microfibers was also validated by EDX analysis (Fig. 2e). The element Ag was clearly detected in the EDX spectrum of Ag3/Chi-CF, whereas the other detected elements corresponded primarily to functional groups in Chi and CF. In addition, the EDX spectrum displayed a small peak corresponding to Ag, confirming the successful impregnation of AgNPs onto the Chi-CF surface.

XRD spectra of CF, Chi-CF, and Ag3/Chi-CF are shown in Fig. 4a. The pattern of pristine CF exhibited diffraction peaks at 14.09°, 16.02°, 20.2°, 22.37°, and 33.93° corresponding to (110), (110), (110), (200), and (004) planes of cellulose 1, respectively33,34. The pattern of Chi-CF is almost similar to CF, however, some new peaks were observed at 8.2°, 12°, and 24°, corresponding to the semicrystalline nature of Chi35. Furthermore, the XRD pattern of Ag3/Chi-CF, as a representative of all the AgNPs-loaded strips, showed distinctive peaks at 44.35°, 64.7°, and 77.8°, corresponding to the (200), (220), and (311) planes, respectively, according to JCPDS no. 96-901-3049, in agreement with previous reports36. These results indicate that coating CF with Chi and loading with AgNPs did not alter the inherent crystallinity of cellulose.

Figure 4b shows FTIR spectra of the samples, all of which exhibited characteristic cellulose peaks, consistent with previous literature37. Chi possesses three types of reactive functional groups: a primary amino group at C2, a secondary hydroxyl group at C3, and a primary hydroxyl group at C6. These functional groups facilitate the adsorption of metal cations through electrostatic interaction38. However, due to the relatively low AgNPs content in the samples, as evidenced by EDX analysis (Fig. 2e), FTIR results suggest no significant interaction between the oxygenated functional groups of CF, the amino groups of Chi, and AgNPs. This is supported by the observation that all FTIR peaks remained at the same positions across the spectra14.

The reduction of CR dye was investigated by a UV–vis spectrophotometer using AgNPs-loaded strips as a catalytic material. Figure 5 presents the UV–Vis spectra of CR dye degradation catalysed by Ag/Chi-CF. Typically, the Ag/Chi-CF strip was introduced into 2 mL of a 50 ppm CR solution, followed by the addition of 1 mL of 0.1 M NaBH4. The reaction mixture was monitored at 2-min intervals using the spectrophotometer. Figure 5a shows the UV–Vis absorbance spectra of CR during its reduction by NaBH4 in the presence of Ag3/Chi-CF. A progressive decrease in absorption peak intensity was observed, attributed to the catalytic activity of AgNPs in promoting CR reduction, thereby demonstrating catalyst efficiency.

(a) UV–Vis absorbance spectra of CR dye solution during reduction with NaBH4 using a Ag3/Chi-CF as the catalyst over time. (b) Temporal changes in CR concentration with and without Ag/Chi-CF strips (NaBH4 only as control). (c, d) Recyclability of Ag3/Chi-CF, showing a gradual decline in catalytic activity over three cycles, indicating good stability and reusability. (e) Percentage degradation of CR at 20 min for Ag1/Chi-CF, Ag2/Chi-CF, and Ag3/Chi-CF.

The highest degradation efficiency was achieved with Ag3/Chi-CF, reaching 88.08% within 20 min, followed by 82.97% and 75.41% for Ag2/Chi-CF and Ag1/Chi-CF, respectively (Fig. 5b, e). Recyclability analysis of Ag3/Chi-CF (Fig. 5c, d, and Table 1) revealed a slight decline in degradation efficiency over three cycles, decreasing from 88.08% to 76.89% in the third cycle. This reduction may be attributed to the loss of surface-bound nanoparticles, which in turn diminishes overall catalytic performance. To provide a comparative analysis of our catalytic system’s efficiency (Ag/Chi-CF) against other recently reported AgNPs-based catalytic systems for wastewater treatment, we have compiled data from recent studies in Table 2.

The degradation kinetics were analyzed using zero-order, first-order, and second-order models, and the coefficients of determination R2 were calculated (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Among the models studied, the second-order kinetic model exhibited the best linear fit, suggesting that the degradation of CR is strongly influenced by the concentrations of both the dye and the reactive species.

Fig. 7 Illustrates the proposed mechanism of the electron transfer reaction between CR dye and NaBH₄, in which NaBH₄ acts as the electron donor, CR as the electron acceptor, and AgNPs as the electron transfer mediator45. The presence of the catalyst plays a critical role in facilitating the degradation reaction via the electron relay effect. Moreover, the incorporation of AgNPs, which possess intermediate redox potential between the donor and acceptor, enhances the efficiency and kinetics of electron transfer. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that the degradation mechanism involves the adsorption of CR (acceptor) and NaBH₄ (donor) onto the surface of the Ag/Chi-CF catalytic strip, where AgNPs mediate the electron transfer process, thereby accelerating the reduction reaction.

Conclusion

In the current study, a simple and cost-effective method was developed for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) immobilized on cotton fabric strips for efficient azo dye degradation. Due to the presence of hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and hydrophobic interactions between Chi and cellulose, a uniform Chi coating was achieved. Moreover, Chi contains three types of reactive functional groups: a primary amino group at C2, a secondary hydroxyl group at C3, and a primary hydroxyl group at C6, which facilitate the adsorption of silver ions (Ag⁺) via electrostatic interactions. The synthesized AgNPs exhibited notable catalytic performance in the reduction of Congo red (CR) dye. The catalytic activity increased from 75.4 to 88.08% as the Ag⁺ concentration increased from 100 to 300 ppm. The reduction of CR dye followed second-order kinetics, with a calculated rate constant of 0.1 min−1 for Ag3/Chi-CF. Thus, this study demonstrates an effective and environmentally friendly approach for the preparation of AgNP-based catalysts suitable for industrial dye wastewater treatment. Furthermore, the proposed method is simple, robust, economical, and free from toxic solvents, making it highly promising for scalable applications. However, several limitations should be addressed in future work. For instance, long-term stability and reusability of Ag/Chi-CF under real-world conditions should be investigated to ensure sustained performance. Additionally, toxicity assessments of immobilized AgNPs through in vivo studies are necessary to evaluate the safety and environmental impact of Ag/Chi-CF for practical applications.13

Data availability

We would like to clarify that the raw data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zeleke, M. A., Khan, A. A., Lavrenčič Štangar, U., Mequanint, K. & Kwapinski, W. Garlic (Allium sativum) extract mediated synthesis of self-redox SnO2 nanomaterials for reduction of Cr(VI) under dark condition. Surf. Interfaces 71, 106869 (2025).

Sharma, K., Rajan, S. & Nayak, S. K. Water pollution: Primary sources and associated human health hazards with special emphasis on rural areas. Water Resour. Manag. Rural Dev. Chall. Mitig. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18778-0.00014-3 (2024).

Nishmitha, P. S. et al. Understanding emerging contaminants in water and wastewater: A comprehensive review on detection, impacts, and solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 18, 100755 (2025).

Benhadria, Eh. et al. Copper oxide nanoparticles-decorated cellulose acetate: Eco-friendly catalysts for reduction of toxic organic dyes in aqueous media. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 284, 137982 (2025).

Wang, J. & Azam, W. Natural resource scarcity, fossil fuel energy consumption, and total greenhouse gas emissions in top emitting countries. Geosci. Front. 15, 101757 (2024).

Awais, et al. Catalytic degradation of dyes using gold nanoparticles supported over chitosan coated cotton cloth composite. Mater. Res. Express. 12, 015008 (2025).

Ullah, S. et al. Enhanced photoactivity of BiVO4/Ag/Ag2O Z-scheme photocatalyst for efficient environmental remediation under natural sunlight and low-cost LED illumination. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 600, 124946 (2020).

Al-Tohamy, R. et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 231, 113160 (2022).

Parida, V. K. et al. Insights into the synthetic dye contamination in textile wastewater: Impacts on aquatic ecosystems and human health, and eco-friendly remediation strategies for environmental sustainability. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIEC.2025.04.019 (2025).

Chandanshive, V. et al. In situ textile wastewater treatment in high rate transpiration system furrows planted with aquatic macrophytes and floating phytobeds. Chemosphere 252, 126513 (2020).

Nahar, N., Haque, M. S. & Haque, S. E. Groundwater conservation, and recycling and reuse of textile wastewater in a denim industry of Bangladesh. Water Resour. Ind. 31, 100249 (2024).

Dutta, P., Razaya Rabbi, M., Sufian, M. A. & Mahjebin, S. Effects of textile dyeing effluent on the environment and its treatment: A review. Eng. Appl. Sci. Lett. (EASL) 5, 1–17 (2022).

Singha, K., Pandit, P., Maity, S. & Sharma, S. R. Harmful Environmental Effects for Textile Chemical Dyeing Practice (Elsevier, 2021).

Awais Ali, N., Khan, A., Asiri, A. M. & Kamal, T. Potential application of in-situ synthesized cobalt nanoparticles on chitosan-coated cotton cloth substrate as catalyst for the reduction of pollutants. Environ. Technol. Innov. 23, 101675 (2021).

Jamil, I. et al. A review of the gold nanoparticles’ synthesis and application in dye degradation. Clean. Chem. Eng. 10, 100126 (2024).

Naeem, H., Ajmal, M., Muntha, S., Ambreen, J. & Siddiq, M. Synthesis and characterization of graphene oxide sheets integrated with gold nanoparticles and their applications to adsorptive removal and catalytic reduction of water contaminants. RSC Adv. 8, 3599–3610 (2018).

Kodasi, B. et al. Novel jointured green synthesis of chitosan-silver nanocomposite: An approach towards reduction of nitroarenes, anti-proliferative, wound healing and antioxidant applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 246, 125578 (2023).

Soto, K. M. et al. Rapid and facile synthesis of gold nanoparticles with two Mexican medicinal plants and a comparison with traditional chemical synthesis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 295, 127109 (2023).

Bharathi, A. et al. Microscopic characterization based synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Merremia quinquefolia (L.) Hallier f. leaf extract: their biological approaches and degradation of methylene blue dye. Microsc. Res. Tech. 88, 1664–1680 (2025).

Ogundare, S. A. et al. Catalytic degradation of methylene blue dye and antibacterial activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Peltophorum pterocarpum (DC.) leaves. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2, 247–256 (2023).

Hijazi, B. U., Faraj, M., Mhanna, R. & El-Dakdouki, M. H. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles as a reliable alternative for the catalytic degradation of organic dyes and antibacterial applications. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 8, 100408 (2024).

Ali, N. et al. Chitosan-coated cotton cloth supported copper nanoparticles for toxic dye reduction. Int J Biol Macromol 111, 832–838 (2018).

Benhadria, Eh. et al. Eco-friendly Cu₂O/Cu nanoparticles encapsulated in cellulose acetate: A sustainable catalyst for 4-nitrophenol reduction and antibacterial applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13, 115077 (2025).

Garg, N., Bera, S., Rastogi, L., Ballal, A. & Balaramakrishna, M. V. Synthesis and characterization of L-asparagine stabilised gold nanoparticles: Catalyst for degradation of organic dyes. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 232, 118126 (2020).

Benhadria, Eh. et al. Cellulose acetate-stabilized Cu2O nanoparticles for enhanced catalytic reduction of organic pollutants. J. Inorg Organomet Polym Mater 35, 3325–3343 (2025).

Debnath, P. & Ray, S. K. Synthesis of sodium alginate grafted and silver nanoparticles filled anionic copolymer polyelectrolytes for adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of a cationic dye from water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 285, 138228 (2025).

Ahmad, A. et al. Catalytic degradation of various dyes using silver nanoparticles fabricated within chitosan based microgels. Int. J. Biol Macromol 283, 137965 (2024).

Ul-Islam, M. et al. Chitosan-based nanostructured biomaterials: Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. search 7, 79–99 (2024).

Yadav, H., Malviya, R. & Kaushik, N. Chitosan in biomedicine: A comprehensive review of recent developments. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. and Appl. 8, 100551 (2024).

Jiménez-Gómez, C. P., Cecilia, J. A., Guidotti, M. & Soengas, R. Chitosan: A natural biopolymer with a wide and varied range of applications. Molecules 25, 3981 (2020).

Strnad, S. & Zemljič, L. F. Cellulose—Chitosan functional biocomposites. Polymers 15, 425 (2023).

Joseph, B., Sagarika, V. K., Sabu, C., Kalarikkal, N. & Thomas, S. Cellulose nanocomposites: Fabrication and biomedical applications. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 5, 223–237 (2020).

Ali, F. et al. Chitosan coated cotton cloth supported zero-valent nanoparticles: Simple but economically viable, efficient and easily retrievable catalysts. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–16 (2017).

Klemm, D., Heublein, B., Fink, H. P. & Bohn, A. Cellulose: Fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angewandte Chemie—Int. Ed. 44, 3358–3393 (2005).

Kumar, M. S., Selvam, V. & Vadivel, M. Synthesis and characterization of silane modified iron (III) oxide nanoparticles reinforced chitosan nanocomposites. Eng. Sci. Adv. Tech. 2, 1258–1263 (2012).

Faghihi, K. & Shabanian, M. Thermal and optical properties of silver-polyimide nanocomposite based on diphenyl sulfone moieties in the main chain. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 56, 665–667 (2011).

Abidi, N., Cabrales, L. & Haigler, C. H. Changes in the cell wall and cellulose content of developing cotton fibers investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohyd. Polym. 16(100), 9–16 (2014).

Piotrowska-Kirschling, A. & Brzeska, J. Review of chitosan nanomaterials for metal cation adsorption. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin Deriv. 25, 51–62 (2020).

Vinayagam, R. et al. Peltophorum pterocarpum flower mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its catalytic degradation of acid blue 113 dye. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–11 (2025).

Ali, S. et al. Photocatalytic removal of textile wastewater-originated methylene blue and malachite green dyes using spent black tea extract-coated silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–17 (2025).

Varadavenkatesan, T., Nagendran, V., Vinayagam, R., Goveas, L. C. & Selvaraj, R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Lagerstroemia speciosa fruit extract: Catalytic efficiency in dye degradation. Mater. Technol. 40, 2463955 (2025).

Narváez-Muñoz, C. et al. Polyacrylonitrile/silver nanoparticles composite for catalytic dye reduction and real-time monitoring. Polymers 17, 1762 (2025).

Maity, A., Bhaumik, D. M. & Brink, H. G. Effective degradation of congo red dye in aqueous solution using highly recyclable silver nanoparticles decorated polyaniline nanowires. (2025) https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.5334775

Selvaraj, R. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles from rubber fig leaves and their application in the catalytic degradation of Congo Red dye. Mater. Technol. 40, 2498585 (2025).

Pal, T. et al. Organized media as redox catalysts. Langmuir 14, 4724–4730 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) under the 2023 Translational Research Program for the Energy Sustainability Focus Area (Project ID: MMUE/240001), the 2024 ASEAN IVO (Project ID: 2024-02), and Multimedia University, Malaysia

Funding

Dr. It Ee Lee has provided funding for the manuscript title: Chitosan Coated Cotton Fabric Embedded with Silver Nanoparticles for Azo Dye Degradation in Aqueous Solutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hajra Bibi: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization and Writing original draft. Abrar Ali khan: Data curation, Conceptualization. It Ee Lee, and Qamar Wali: Resources, Supervision, & Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bibi, H., Khan, A.A., Lee, I.E. et al. Chitosan coated cotton fabric embedded with silver nanoparticles for azo dye degradation in aqueous solutions. Sci Rep 15, 39644 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23222-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23222-5