Abstract

Pavement performance assessment and prediction are crucial for efficient infrastructure management and strategic planning of maintenance activities. Conventional techniques are insufficient and lack the efficiency and flexibility required for modern transportation networks. This study proposes a groundbreaking integrated approach that merges machine learning (ML) classification techniques with Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to evaluate road conditions using the Pavement Condition Index (PCI) and the International Roughness Index (IRI). Given that IRI data collection is more straightforward and cost-effective than gathering pavement distress data, this study aims to classify the IRI of flexible pavements to estimate PCI models using advanced ML algorithms (Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Trees (DT), and Random Forest (RF)) and accurately determine pavement conditions. This research gathered 1042 data points using a smartphone application, TotalPave, to measure the IRI values for the (Nizwa–Muscat) and (Muscat–Nizwa) routes in the Sultanate of Oman. It meticulously applied feature selection techniques to identify the pavement parameters significantly impacting pavement performance. The research then spatially visualized and analyzed the results to determine the critical pavement sections. Among the ML models, RF demonstrated outstanding performance with an accuracy rate of 99.9% and an F1-score of 99. SVM has the lowest accuracy of 85.8% and an F1-score of 40.3. A comprehensive assessment comprising a confusion matrix, uncertainty analysis, box and whisker plot, and noise sensitivity provides in-depth insights into the reliability and consistency of predictions. The ML and GIS methods revolutionized the way transportation agencies interpret and implement their findings. The proposed framework is not merely a tool, but a transformative solution that facilitates the formulation of proactive maintenance strategies and optimizes resource utilization by providing a scalable and intelligent decision-support tool designed specifically for pavement management systems (PMS).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reliable pavement data is essential in designing an effective pavement management system (PMS), ensuring accurate assessment, timely maintenance and rehabilitation (M&R), and efficient resource allocation1,2. Inadequate data undermines infrastructure performance and increases costs. Automated data collection is critical in ensuring sustainable and cost-effective roadway management3,4. Numerous programs are available globally for predicting road conditions, planning investments, and selecting suitable maintenance strategies5,6. PMS is critical in supporting these decisions by providing data-driven insights7. Regular preventive maintenance helps delay pavement deterioration and ensure long-term serviceability8. Investment in M&R enhances safety, reduces costs, and improves driving comfort9. Table 1 presents the Pavement Condition Index (PCI), which ranges from 0 to 100, for evaluating surface damage and roughness based on distress type, severity, and extent.

Numerous studies employed PCI to develop and refine pavement preservation strategies10,11,12. For instance, a comprehensive research in South Korea found that micro-surfacing as a preservation treatment emphasized the importance of matching techniques with functional and structural pavement conditions13. The evaluations revealed that distresses like rutting, alligator cracking, and longitudinal cracking have a significant impact on PCI calculations. Loprencipe et al.14 developed a PCI-based PMS to enhance urban pavement network management. Instead of employing traditional manual surveys to collect PCI data, recent studies investigated the effectiveness of automated data collection methods. While efficient, these methods may not be able to capture emergency or subtle distress features, potentially leading to overestimated PCI values. Ahmed et al.15 explored utilizing multiple linear regression (MLR) models to estimate PCI by supervising the IRI dataset, which was a quantitative measure of pavement surface smoothness and ride quality. They established the riding quality under the World Bank’s auspices in 1986 and calculated the IRI by measuring the cumulative vertical displacements over a given distance, typically using a laser profiler16. IRI (expressed in meters per kilometer (m/km)) is a measure of road roughness, and lower values indicate smoother pavements. The US Federal Highway Administration classifies pavements for high-speed roadways with an IRI exceeding 2.7 m/km as being in poor condition8. The open-ended IRI scale in Table 2 and Fig. 1 presents the IRI-based classification system for pavement ride quality.

Adapted IRI roughness scale18.

Researchers have highlighted the significance of IRI as a critical indicator of serviceability, linking it to user comfort and traffic safety11,19. Several studies exploring the correlations between IRI and pavement distress types emphasized its role as a critical performance indicator throughout the pavement lifecycle20,21,22,23,24. Both PCI and IRI offer valuable insights into pavement performance. While PCI helps identify the severity of surface distress, IRI is an indicator of ride quality and smoothness.

Researchers often used these indices in tandem within PMS to support informed decision-making, from routine maintenance to rehabilitation planning. For instance, Mousa et al.25 utilized a multilayer elastic analysis tool, KENLAYER, to assess structural responses, for example, tensile and vertical stress, in pavements containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). In summary, integrating PCI and IRI metrics provides a holistic view of pavement condition, thus ensuring more effective management strategies that balance both adequacy and ride comfort.

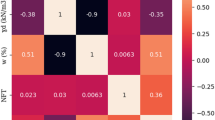

This study investigates the distinct roles and correlation between PCI and IRI in pavement performance assessments26. PCI allows a detailed evaluation of structural and functional distress, making it a reliable benchmark for pavement health27. In contrast, although IRI lacks the depth of PCI, it provides a quick measure of ride quality based on surface smoothness28. Despite IRI’s variability due to measurement techniques and vehicle type, combining both indicators enhances understanding and supports better maintenance planning29,30,31,32. Table 3 provides an overview of studies employing these models to evaluate pavement performance.

Machine learning (ML) models are automated data analysis tools utilized to identify patterns within datasets, which help predict future data or facilitate decision-making in uncertain situations40. There are two primary ML techniques, supervised and unsupervised learning41. There has been increasing interest in employing ML to predict pavement conditions in recent years to improve the accuracy and reliability of maintenance planning and assess the conditions of transportation infrastructure42,43,44.

Park et al.33 verified that IRI is a valid predictor variable for PCI and can explain most variations in PCI. Pantha et al.45 utilized GIS to develop a maintenance model that considers pavement conditions and the stability of roadside slopes, where IRI serves as an indicator of pavement conditions. Heyns et al.46 formulated a strategy for prioritizing the construction of rural roads in Nepal’s Karnali province, demonstrating superior results in terms of accessibility, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness compared to those chosen by the provincial authorities.

Mallika et al.47 investigated the performance of an ANN model compared to IRI models in predicting ionospheric Total Electron Content (TEC) values. Gong et al.48 found that the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Locally Weighted Polynomials (LWP) models outperformed other techniques, such as PSO-ANFIS and PSO-ANN, in accurately predicting IRI. Pandit et al.49 obtained promising results by employing an ANN and XGB-Regressor to predict IRI for Indian road conditions50. Pandit et al.49 utilized SVR, RF, ANN, GPR, Extra-trees, and GB to forecast IRI.

Hoang and Nguyen51 employed seven ML methods (SVM, RF, ANN, Classification Tree (CT), Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN), and Naïve Bayesian Classifier (NBC)) to examine pavement deterioration. Nabipour et al.52 utilized GEP and SVM techniques to predict the remaining service life of pavements. Kirbas and Karasahin53 investigated an ANN and MLR that used PCI to calculate pavement performance models.

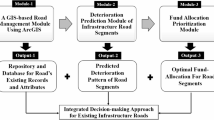

The literature review revealed that few researchers have explored combining ML classification techniques with GIS to evaluate IRI and PCI. The integration of ML classification with GIS techniques has significantly enhanced the approaches for assessing pavement conditions. However, the combination of ML and GIS facilitated spatial representation and examination of pavement conditions, thus supporting decision-making in maintenance planning54. Elshaboury et al.55 employed GIS spatial analysis tools to predict PCI values by utilizing nine Bayesian-optimized models and demonstrated the advantages of spatial analysis in identifying areas requiring urgent repairs. Additionally, GIS data enhanced the capabilities of an integrated ML and GIS. Mohamed et al.54 developed a framework combining genetic algorithms with GIS for large-scale pavement condition monitoring. Integrating ML classification techniques with GIS provided a robust framework for pavement condition assessment56. It improved accuracy, enabled automation, and facilitated better-informed maintenance decisions through spatial analysis and visualization.

The primary focus of this study is to use ArcGIS Pro 3.3 software to integrate ML classification techniques with geospatial analysis to develop dependable pavement performance indices. Utilizing a case study approach, the research will identify the critical factors affecting pavement conditions, classify various levels of pavement performance, and create spatially informed performance maps that facilitate data-driven decision-making in the maintenance and management of pavements.

This study advances PMS by combining ML classification with geospatial analysis in ArcGIS Pro 3.3 to create a scalable, data-driven framework for pavement evaluation. It selects Ad Dakhiliyah, Oman, as the study area to address the impact of traffic and climate on road durability. The approach enhances assessment accuracy, supports proactive maintenance, and informs policy and resource planning. It also offers a transferable model for other regions facing similar challenges, thus benefiting planners, engineers, and researchers in smart infrastructural development.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the location of the study area, data collection and processing, the Natural Breaks (Jenks) classification for PCI, and the IRI distribution mapping. It also presents a detailed description of the ML models.

Location of the study area

The study area is the Ad Dakhiliyah Governorate in the northeastern part of the Sultanate of Oman. It has strategic significance as a crucial transportation corridor connecting interior cities with the capital region, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The pavement stationing spans from 35 + 885 to 134 + 040, encompassing a section of the national highway road network. Geographically, the study area is approximately at latitude 22°50′N and longitude 57°30′E. It has arid climatic conditions, diverse topography, and varying traffic volumes.

The study area, showing the elevation details and highways (marked in black), Esri ArcGIS Pro 2025 (https://www.esri.com/).

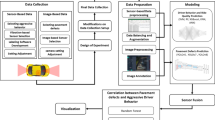

Data collection and processing

This study developed a simple, cost-effective method for estimating PCI using the IRI. The proposed approach emphasizes an efficient and accurate collection of IRI data across the study area to establish a reliable correlation with PCI57. Such a cost-effective methodology is especially beneficial in scenarios where traditional pavement assessment techniques are financially or logistically unfeasible. The investigation focused on a system of flexible national highways spanning 98.155 km.

The data collection comprises a desk study and fieldwork. The desk study phase examined the existing data and classification systems along the Nizwa–Muscat and Muscat–Nizwa routes, followed by a detailed field survey to document the surface distresses in asphalt pavements and estimate the PCI values. Utilizing a mobile device application (TotalPave) to make IRI measurements ensured a practical and cost-effective data acquisition. The test vehicle was driven at standard arterial speeds (20–80 km/h) within the traffic lane while maintaining a central alignment along the left wheel path32. Upon reaching a steady speed, the TotalPave application was activated to begin data recording. The data was uploaded to the TotalPave web service after completing the survey of each section to generate the IRI values for every 100-m segment. The web platform provides downloadable Excel files containing IRI data at 100-m intervals. Each section underwent three surveys to ensure the reliability of the measurements, and the average IRI value was employed. The variation between the maximum and minimum IRI readings was less than 2%, indicating consistency and reliability of the data. The next step involved considering the mathematical forms used in the prediction models in the current literature to develop a classification model for identifying the relationship between the IRI and the PCI.

Natural breaks (Jenks) classification for the PCI and IRI distribution mapping

The Jenks optimization technique, also known as the Natural Breaks method, was employed to classify and visualize the distribution of PCI and IRI data along the Nizwa–Muscat and Muscat–Nizwa routes. The method determines the breakpoints by reducing the variance within groups and increasing the variance between them58. Natural Breaks are notably advantageous for environmental datasets with skewed distributions since they emphasize the inherent patterns in the data59.

This study established five categories based on the distribution of the predicted values. Figure 3 illustrates the detailed methodological framework employed in this study. The process commences with data collection and preprocessing, followed by model training and validation. It then used the Natural Breaks method to segment the continuous probability surface into distinct suitability categories and generate the predicted outputs. This classification facilitates the creation of the final thematic maps for interpretation and decision-making. The workflow ensures a transparent and reproducible approach to modeling and visualization. This classification approach enabled more meaningful comparisons between the directions of the routes and facilitated the identification of the critical segments requiring maintenance based on their natural grouping within the overall condition assessment60.

Machine learning models

The increasing popularity of ML in pavement engineering applications is due to its efficiency in solving complex engineering problems61. PMS research often integrates predictive models to assess pavement performance and optimize M&R strategies. In this study, a MATLAB application used to develop ML techniques, including artificial neural networks (ANN), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees (DT), and Random Forests (RF), are popular for developing classification and regression models. Moreover, In this study, Bayesian hyperparameter optimization with 20-fold cross-validation was employed for rigorous and efficient model tuning. This approach uses probabilistic surrogate models, typically Gaussian processes, to approximate the objective function and iteratively select hyperparameter configurations that maximize expected improvement, reducing evaluations compared to exhaustive search. The process began by defining the hyperparameter search space and creating an objective function to return the maximum based on metrics for classifier performance such as accuracy and F1-score62. A Gaussian process model was initialized with a small set of random configurations, and the dataset was split into 20 folds, with 19 used for training and 1 for testing in each iteration. This ensured all folds served as validation data, allowed performance variation assessment, and minimized overfitting risk. Averaging results across folds provided a stable and reliable performance estimate. Figure 3 presents the model framework.

Hyperparameter optimization for ML models

In this study, Bayesian optimization (BO) was utilized to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the ML models. ML includes a range of algorithms, such as discriminator analysis, ANN, AdaBoost, SVM, DT, and RF, to assess classifier performance for an ML repository involves utilizing various metrics to understand how well a classification model performs62,63. The RF algorithm was found to deliver the best classification results. Consequently, BO was initially applied to adjust the RF algorithm’s hyperparameters. It was then used to optimize ANNs, as well as SVM, DT, and AdaBoost. Table 4 provides a summary of the hyperparameters and their default values for the models in this study. For the ANN, the hyperparameters consist of one hidden layer, ten neurons per layer, a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, a learning rate of 0.01, a Stochastic Gradient Descent SGD optimizer, 100 epochs, and a batch size of 32. AdaBoost is set up with 50 estimators, a learning rate of 1.0, and a decision stump as the base estimator. The SVM defaults include an RBF kernel, C = 1.0, gamma set to “scale,” and a polynomial kernel degree of 3. The DT model employs a maximum depth of None, a minimum of one sample per leaf, and the Gini index as the splitting criterion. The RF algorithm is configured with 100 trees, no maximum depth, and a minimum of two samples per split. These initial hyperparameter settings serve as the foundation for BO, which is systematically applied to enhance model performance.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

ANNs are sophisticated analytical models inspired by the architecture and operations of the human brain, developed to handle data and identify patterns through layers of interconnected nodes, or neurons64. These networks are extensively employed in tasks such as classification, regression, and pattern recognition. Figure 4 shows the diagram of the ANN algorithm.

An ANN generally comprises an input layer that receives raw data, one or more hidden layers where computations and feature extraction occur, and an output layer that delivers the final prediction or classification outcome. The weights and biases are adjusted throughout the network during training to minimize error and improve accuracy. Additionally, activation functions such as ReLU or sigmoid are applied to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to model complex relationships in the data. Equation (1) is the single-layer ANN perceptron for classification.

where \(\acute{y}\) is the predicted output (probability for classification), \({x}_{i}\) is the input features, \({w}_{i}\) is the weights, \(b\) is the bias, and \(\sigma\) is the activation function (for instance, sigmoid: \(\sigma (z)=\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-z}}\)).

Adaptive boosting (AdaBoost)

AdaBoost is an ensemble learning method used for classification (and sometimes regression) in ML65. The idea behind AdaBoost is to combine multiple weak classifiers, usually decision stumps, a one-level DT, to form a strong classifier. Figure 5 presents the structure of the AdaBoost algorithm.

Diagram of the AdaBoost algorithm40.

AdaBoost works by iteratively training classifiers, each focusing more on the instances that the previous ones misclassified66. Equations (2) and (3) give the final prediction \(H(x)\) for input \(x.\)

where \(T\) is the number of weak classifiers, \({h}_{t}(x)\) is the prediction of the \({t}^{th}\) weak classifier, and \({\alpha }_{t}\) is the weight of the \({t}^{th}\) classifier, calculated as:

\({\varepsilon }_{t}\) is the error rate of \({h}_{t}\) on the weighted training data, and \(sign(\cdot )\) returns + 1 or -1 based on the sign of the result.

Support vector machine (SVM)

SVM is a superior supervised ML algorithm used primarily for classification tasks, although it is also suitable for regression67. The main goal of SVM is to find the optimal hyperplane that best separates the data points of different classes in a feature space. Figure 6 shows the diagram of the SVM algorithm.

Furthermore, SVM aims to maximize the margin between the two classes, the distance between the hyperplane, and the nearest data points from each class (called support vectors)68. Equation (4) of SVM for Binary Classification, which leads to the decision boundary (hyperplane) in an n-dimensional space, is given by:

where \(w\) is the weight vector (normal to the hyperplane), \(x\) is the input feature vector, \(b\) is the bias (offset from the origin), and the dot product \(w\cdot x\) measures the projection of \(x\) onto \(w\). Classification Rule: For a new input \(x\), the predicted class \(y\) is

-

If \(w\cdot x+b>0\), then \(y=+1\)

-

If \(w\cdot x+b<0\), then \(y=-1\)

Decision trees (DT)

Decision Trees (DTs) are a supervised ML algorithm employed for classification and regression tasks69. They function by partitioning the data into subsets based on feature values, thereby creating a tree-like model of decisions. Each internal node signifies a decision based on a feature, each branch represents the outcome of the decision, and each leaf node denotes a class label in the context of classification. The features of Decision Trees include ease of interpretation and visualization, the ability to handle numerical and categorical data, and the capability to model non-linear decision boundaries. Figure 7 is the algorithm for a Decision Tree.

Diagram for the DT algorithm70.

Unlike linear models that use Eqs. 6, 7, and 8, DT employs a recursive method to divide the dataset based on a specific criterion. The most common splitting criteria are the Gini Impurity (used in CART Classification and Regression Trees).

where \(D\) is the dataset, \(C\) is the number of classes, \({p}_{i}\) is the probability of class \(i\) in dataset \(D\)

Entropy (used in ID3 algorithm):

The Information Gain is computed to identify the best feature to split.

where \(A\) is the attribute, and \({D}_{v}\) is a subset of \(D\) for which attribute \(A\) has value \(v\).

Random forest (RF)

Breiman71 established an RF, a superior ensemble ML method for classification and regression tasks[NO_PRINTED_FORM]. RF improves prediction accuracy and reduces the overfitting problem commonly associated with DT. It combines predictions from multiple DTs to produce a more accurate and stable prediction. Figure 8 presents the algorithm for an RF.

Diagram for the RF algorithm40.

A critical component in RF’s functionality is the evaluation of feature significance assessed using the Gini impurity metric. Equation (9) employs class and probability to determine the Gini impurity for each branch of a node and identify the branches with a higher likelihood of occurrence72. The Gini impurity is expressed as follows:

where C is the number of distinct classes, and pi is the probability of encountering class i within a specific node and quantifies the purity of a node. The objective of minimizing the Gini impurity in the tree construction process underpins the RF algorithm’s capability to enhance the homogeneity of the nodes, thereby enhancing the overall precision and robustness of the predictive model.

Evaluation of model performance

The confusion matrix is a practical tool for assessing the performance of an ML algorithm. It provides a comprehensive overview of how a classification model’s actual and predicted results align against each other73. The confusion matrix is three-dimensional and comprises the sample’s actual and expected indices. Based on the classification prediction results, this research utilized six indicators to evaluate the performance of the ML model. The true positive rate (TPR), also known as sensitivity or recall, measures the proportion of actual positive cases that the model correctly identifies as positive. The true negative rate (TNR) (or specificity) calculates the fraction of negative instances that the model accurately identifies as negative. Conversely, the positive predictive value (PPV) (or precision) determines the percentage of predicted positive instances that were indeed positive. Finally, the negative predictive value (NPV) assesses the percentage of predicted negative instances that were negative74. The overall accuracy of an ML model can be evaluated using the accuracy and F-measure, where the F-measure represents the harmonic mean of recall and precision75. Equations (10)–(15) are as follows.

where TP and TN are the number of correctly predicted positive (true positive) and negative class (true negative), respectively, while FP and FN represent the number of incorrectly predicted positive (false positive) and negative class (false negative), respectively.

Result and discussion

Spatial distribution maps of IRI and PCI

This research employed the Jenks algorithm in ArcGIS Pro 3.3 software (Esri, 2024) to map and classify the spatial distribution of IRI and PCI in the study area because of its efficiency in segmenting values into distinct categories by reducing the variance within each category and enhancing the variance between them. Figure 9a,b show the spatial distribution of IRI and Fig. 10a,b present the spatial distribution of PCI in the study area. This method is particularly advantageous for the pavement condition analysis in this study because it produces statistically significant categories, avoids reliance on arbitrary intervals, identifies inherent groupings within the data, and emphasizes notable differences between route segments76.

Spatial layout of the IRI. (a) The IRI along the Muscat–Nizwa route, and (b) The IRI along the Nizwa–Muscat route, ArcGIS Pro 3.3. (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

Spatial distribution of PCI. (a) The PCI along the Muscat–Nizwa route, and (b) The IRI along the Nizwa–Muscat route, ArcGIS Pro 3.3 (https://pro.arcgis.com/).

IRI offers a definitive analysis of ride quality and surface smoothness. The analysis in this research revealed that the average IRI was 1.849 m/km for the Nizwa–Muscat route and 1.874 m/km for the Muscat–Nizwa route (Fig. 11a). IRI values of under 2 m/km indicate a good to excellent ride quality, which provides road users with acceptable comfort levels. The comparable median IRI values of 1.587 m/km and 1.691 m/km support the conclusion that both routes provide smooth riding conditions. Interestingly, the minimum IRI was significantly lower for the Nizwa–Muscat route (0.376) than for Muscat–Nizwa (0.732), indicating sections with exceptionally smooth surfaces.

On the other hand, the maximum IRI for Nizwa–Muscat (4.973) was higher than the 4.402 IRI for Muscat–Nizwa. The higher readings indicate localized roughness exceeding 4 m/km, a threshold commonly associated with poor ride quality and increased vehicle wear. The higher standard deviation for the Nizwa–Muscat route (0.771) compared to the Muscat–Nizwa route (0.661) suggests more variability in surface conditions (Fig. 11a). This variability indicates that while many segments meet high standards, isolated sections of rough pavement could negatively impact user experience and safety.

The PCI analysis revealed that the Nizwa–Muscat and Muscat–Nizwa routes have favorable pavement conditions. The mean PCI was 78.49 for the Nizwa–Muscat and 78.08 for the Muscat–Nizwa routes (Fig. 11b). PCI values ranging from 70 to 85 are typically classified as good, signifying that the pavements are in sound structural condition with only minor surface distress requiring routine maintenance. The median PCI values were also closely aligned (80.85 for Nizwa–Muscat and 79.72 for Muscat–Nizwa), confirming the overall consistency in pavement performance along the corridor (Fig. 11b).

There are disparities in the distribution of PCI values for the two routes. The Nizwa–Muscat route had a lower minimum PCI of 51.36 compared to 55.44 for the Muscat–Nizwa route, indicating that some localized pavement segments are approaching a fair condition. The sections with PCI within this range typically display moderate distress and require more intensive maintenance to prevent further deterioration. The higher maximum PCI of 95.08 for the Nizwa–Muscat route suggests that some segments have benefited from recent rehabilitation or resurfacing efforts. The standard deviation for the Nizwa–Muscat route (7.64) was higher than in the Muscat–Nizwa route (6.56), indicating greater variability in pavement condition. Although much of the corridor is in satisfactory condition, maintenance practices and surface performance were not consistent throughout the Nizwa–Muscat route. From a management perspective, this variability necessitates targeted inspections and focused preventive maintenance to manage the weaker sections and maintain overall serviceability.

IRI classification and validation

IRI classification

The IRI classification analysis evaluated the models using six metrics (AUC, CA, F1-score, Precision, Recall, and MCC), and the results provided significant insights into the performance of ML models. Ensemble approaches, particularly Adaboost and RF, provided exceptional results across all metrics. The scores for Adaboost were 99.99% for AUC, 99.99% for CA, and 99.99% for MCC, and those for FR were 100% for AUC, 99.9% for CA, and 99.9% for MCC. These models consistently outperformed others, as depicted by the bold blue lines in the Sankey diagram (Fig. 12a). The Tree model showed strong performance, with scores of 99.7% for AUC, 99.6% for CA, and 99.5% for MCC.

While Adaboost and RF may perform slightly better, DT stands as a robust and reliable choice for IRI classification tasks. The ANN, with an impressive AUC of 99.9%, demonstrated its potential to provide opportunities to enhance the balance between precision and recall, as indicated by its MCC of 96.2%. On the other hand, SVM underperformed with a dismal MCC of 13.5% and an F1-score of 40.3%. The thin red links in the Sankey diagram (Fig. 12b) illustrate its inadequacies for IRI classification and emphasize the need for more robust alternatives.

In classification, ensemble methods proved to be the best choice with their unparalleled ability to adeptly manage the complexities of intricate IRI datasets while consistently delivering outstanding accuracy across all metrics. The subpar performance of SVM unmistakably highlights its inadequacy for IRI tasks that demand a harmonious balance of metrics, such as Precision and Recall. Conversely, DT was a reliable alternative, while ANN failed to achieve the metric equilibrium demonstrated by the leading ensemble methods. The evidence is compelling: ensemble methods are unequivocally the superior option for those seeking to excel in IRI classification tasks.

IRI validation

The validation results substantiated the superiority of ensemble methods, particularly Adaboost and DT, in IRI analysis. Both models achieved perfect scores across all metrics, including AUC (100%), CA (100%), F1-score (100%), Precision (100%), Recall (100%), and MCC (100%). The prominent green links connecting these models to all metrics in the Sankey diagram underscore their exceptional reliability during validation (Fig. 12a).

The RF model exhibited extraordinary performance, achieving near-perfect scores of 99.9% AUC, 99.9% CA, and 99.9% MCC (Fig. 12b). The remarkable consistency between classification and validation unequivocally highlights the unparalleled robustness of RF for high-stakes IRI analysis tasks. In stark contrast, while ANN showed a slight improvement during validation, with an AUC of 100%, it demonstrated a notable decline in MCC to 96.5%. This inconsistency reveals a concerning sensitivity to dataset variations, most notably balancing precision and recall. Similarly, the validation of SVM revealed poor performance, with scores of 19.2% MCC and 45.3% Precision, underscoring its inadequacy for such critical tasks.

Even though CA achieved a slightly higher score of 74.9%, its consistently poor performance across most metrics strongly indicates its unsuitability for IRI datasets that require balanced contributions (Fig. 12b). The comparison of classification and validation results highlights the superiority of ensemble methods, such as Adaboost and DT, which consistently excelled in both phases. These models maintained their performance during validation, affirming their robustness for IRI analysis tasks. RF also demonstrated remarkable stability between classification and validation, thus establishing itself as a reliable choice for near-perfect outcomes.

Although ANN showed moderate consistency, it did not match the performance of the ensemble methods because of its lower scores in critical metrics, such as MCC, in both phases. SVM’s consistent underperformance across the classification and validation phases revealed its inadequacies in managing complex IRI datasets that require balanced contributions to key metrics.

PCI classification and validation

PCI validation

The validation results confirmed the dominance of ensemble methods (Adaboost and RF) in PCI analysis. Both models achieved perfect scores across all metrics, including AUC (100%), CA (100%), F1-score (100%), Precision (100%), Recall (100%), and MCC (100%). The thick green links connecting these models to all metrics in the Sankey diagram underscored their exceptional reliability during validation (Fig. 13a).

The DT method achieved a near-perfect performance during validation, with scores of 99.9% AUC and 99.5% MCC. The consistency between the classification and the validation phases highlights DT stability as a reliable model for PCI analysis. ANN showed slight improvement during validation compared to classification results, achieving scores of 99.5% AUC and 93% MCC (Fig. 13b). However, it remained behind Adaboost, RF, and DT in overall performance.

SVM showed the worst performance during validation, with scores of 0% MCC and 56.2% Precision. Despite achieving a slightly higher score for CA (74.9%), its persistently poor performance across most metrics underscores its incompatibility with PCI datasets requiring balanced metric contributions (Fig. 13b). The comparison of classification and validation results revealed a consistent dominance of ensemble methods (Adaboost and RF) across both phases. These models did not experience reduced performance during validation, thus confirming their robustness for PCI analysis tasks. The DT model also maintained stable performance between classification and validation phases, making it a viable alternative when prioritizing interpretability.

ANN exhibited moderate consistency but lagged behind the ensemble methods due to lower scores for metrics, such as MCC, during both phases. SVM consistently underperformed across both classification and validation phases, highlighting its limitations in handling complex PCI datasets that require balanced contributions to metrics like Precision and Recall.

PCI classification and validation based on IRI

PCI classification based on IRI

This study employed RF, ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM to develop predictive models for PCI using IRI data. It evaluated the model performance based on six classification metrics: AUC, CA, F1-score, precision, recall, and MCC. Table 5 summarizes the metrics for the five models. The DT model demonstrated robust performance, achieving an AUC of 96.2% and consistent scores of 89.8% and 88.9% across CA, F1-score, precision, and recall.

The MCC of 85% confirmed a strong alignment between the predicted and the actual outcomes. Similarly, the ANN model achieved an AUC of 96.1% and matched the DT model in all other evaluation metrics, including an MCC of 85%, indicating balanced and reliable predictive capability. The AdaBoost model produced comparable results, yielding an AUC of 96.1% and identical values for CA, F1-score, precision, recall, and MCC. Therefore, ANN and AdaBoost are equally reliable and consistent with the DT approach. The RF model stood out with the highest AUC of 96.7% and the best precision score of 92.1%, suggesting strong discriminatory power and fewer false positives. However, its CA and recall (81%) are slightly lower than those of the best-performing models.

Therefore, while RF has a good potential in specific classification tasks, its overall MCC of 73.5% suggests moderately proficient but not leading performance. On the other hand, the SVM model underperformed across most metrics. Despite achieving an AUC of 94.4%, its CA and recall of 78.7% mean limited effectiveness with a 65.4% MCC. The DT, ANN, and AdaBoost models delivered superior results across metrics. RF demonstrated a high precision and AUC, while SVM lagged, especially in recall and MCC, making it less suitable for PCI prediction using IRI data.

PCI validation based on IRI

This research gathered 1042 data points and utilized five ML techniques to conduct investigations, using 70% of the dataset for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for network validation. Table 6 presents validation results for the model. The evaluation of model performance used six classification metrics: AUC, CA, F1-score, precision, recall, and MCC. The models demonstrated the ability of the five techniques to accurately predict PCI models based on IRI, where all models performed well, achieving an AUC of 95.5% and consistent scores of 84.2%, 87.1%, 80.8%, 84.2%, and 76.5% in F1-score, precision, recall, and MCC, respectively.

Performance evaluation of the PCI classification models

The performance evaluation of the PCI prediction models involved multiple methods (confusion matrix, uncertainty analysis, box and whisker plot, and noise sensitivity) to gain insight into various aspects of the model behavior, from overall accuracy to sensitivity under input variation. Each method evaluates a particular facet of the model. Collectively, they constitute a comprehensive approach for assessing the accuracy of the PCI prediction model based on IRI data.

Confusion matrix

In the classification exercise, the confusion matrix is a performance assessment tool aggregating the numbers of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). The columns represent the expected counts, and the rows are the real instances from a class. The off-diagonal elements suggest misclassifications, while the diagonal elements represent accurate predictions. The confusion matrix provides the F1 score, recall, and precision for each class, indicating the strengths and weaknesses of the classifier. Recall assesses whether the model can identify all pertinent events, and precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions by a model. Analysis of model performance requires these fundamental statistics, as demonstrated in Fig. 14a–d.

Figure 14 presents the respective confusion matrix for RF, ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM. The AdaBoost model demonstrates a high accuracy, particularly in classifying Fair conditions, by correctly identifying 247 of 248 cases. Although its accuracy is lower for Good pavement conditions (466/536), it excels in precisely identifying Very Good conditions (223/223). The SVM model performs better in identifying Good pavements but is less accurate in classifying Poor pavement conditions. The task of evaluating Poor pavement is particularly challenging for the SVM model because it misclassified Poor pavement conditions as Very Good in 159 instances. However, it correctly identified several Good pavement conditions. Although AdaBoost is an excellent model, the SVM model might be more suitable for precisely identifying Good pavement conditions. AdaBoost generally performs well and excels in the Fair and Very Good categories. Although the RF model might have faced challenges with underrepresented classes (Poor and Very Poor conditions), it was effective for adequately represented classes (Fair and Good conditions). The ANN performed well and excelled in the Fair and Good categories. The SVM often failed to classify Good conditions and misclassified Poor conditions as Very Good. Techniques for managing imbalance could enhance performance standards. The DT performed well in adequately represented classes.

Uncertainty analysis

The confusion matrices for the RF, ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM models revealed common challenges in accurately classifying pavement conditions due to uncertainty. All models had difficulties in reasonably classifying Poor pavement conditions. ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM encountered challenges in distinguishing between Good and Very Good conditions. SVM often misclassified Very Good conditions as Poor, while RF occasionally misclassified Poor conditions as Very Poor. It is essential to explore feature engineering, model tuning, and address data imbalance to enhance classification accuracy. Figure 15 illustrates the uncertainty in the confusion matrices for all ML algorithms.

The RF model demonstrated proficiency in accurately classifying Failed cases and correctly labeled all instances. It also succeeded in classifying 213 instances as Very Poor, although some were incorrectly labeled as Fair, Good, or Very Good. A significant issue observed in the Poor category is that only 19 cases were correctly identified, while most (213 cases) were misclassified as Very Poor, highlighting a considerable challenge in distinguishing between Poor and Very Poor conditions. Furthermore, while the RF model correctly identified 133 Fair cases, it confused others with Failed, Good, and even Very Good, indicating ambiguity in mid-range condition boundaries. Although it correctly classified 425 Good conditions, some were mislabeled as Fair, Poor, or Very Good, underscoring the model’s difficulty in differentiating between Good and adjacent classes. Besides often misclassifying Poor conditions as Very Poor, the RF model also had problems distinguishing between Good and Poor conditions. The ANN model exhibits excellent accuracy in classifying Failed and Very Poor conditions. However, it underperformed in identifying Poor pavement conditions, with most cases assigned as Fair or Very Good and only one correct classification.

For Fair conditions, ANN accurately classified 236 instances and misclassified several others into adjacent categories. Although it also correctly identified 449 Good conditions, the model often misclassified them as Very Good, indicating a tendency to overestimate the quality of the condition. Similarly, ANN correctly identified 210 Very Good conditions but incorrectly assigned a few to lower categories. In summary, the ANN model had difficulty accurately identifying Poor conditions and often confused Good with Very Good conditions.

The DT model accurately labeled Failed and Very Poor conditions. However, it had difficulties identifying Poor conditions, with only one correct Poor classification and misclassifying the remaining as Fair or Very Good. It accurately classified 236 Fair conditions but confused some Fair conditions with adjacent categories. While the model performed well in labeling 449 Good conditions, it also misclassified many as Very Good, indicating a recurring issue. Similarly, the DT model performed well in classifying the Very Good conditions, although it made some misclassifications. Generally, the DT model faced similar difficulties as the ANN model, especially in distinguishing Good and Very Good conditions and identifying Poor conditions. However, the AdaBoost model correctly classified Failed and Very Poor conditions. Nonetheless, it is similar to DT and ANN in facing difficulty with identifying Poor conditions, where it correctly labeled only one instance and confused the remaining Poor conditions with Fair or Very Good. It accurately identified 236 Fair conditions and made comparable misclassifications. The model performed well in correctly classifying 449 Good conditions, although it misclassified some as Very Good. It correctly recognized Very Good conditions in most cases and mislabeled some as lower grades. In summary, AdaBoost faced particular challenges with classifying Poor conditions and often overestimates Good conditions as Very Good.

The SVM model achieved perfect accuracy in classifying Failed and Very Poor conditions, although it had moderate success in classifying the Poor conditions, with only six accurate identifications, while labeling others as Fair or worse. For the Fair condition, the model performed relatively well, with 242 correct classifications and a few errors. Additionally, SVM accurately identified 487 Good conditions but confused some with Very Good conditions. The primary problem was identifying Very Good conditions, where the model correctly classified only 154 instances while classifying many as Poor conditions or other lower categories. This model exhibited a notable flaw in misclassifying Very Good condition as Poor, indicating a reversal in identifying actual conditions. Generally, the consistent challenges for all models are in accurately classifying Poor pavement conditions. ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM had difficulties distinguishing Good and Very Good conditions, and RF often misclassified Poor conditions as Very Poor. SVM erroneously classified Very Good conditions as Poor conditions. These patterns suggest the need to refine the models to enhance identification of mid-level and boundary conditions.

Box and whisker plot

A box and whisker plot, or a box plot, is a standardized graphical method for visualizing data distribution based on five essential summary statistics: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median (Q2), third quartile (Q3), and maximum. The minimum and maximum values (excluding outliers) are represented by the ends of the whiskers, indicating the range of the data. Q1, or the 25th percentile, and Q3, or the 75th percentile, form the lower and upper edges of the box, respectively. The median, or Q2, represents the 50th percentile and is shown as a line inside the box. The data points that fall far from the general trend are considered outliers and displayed as isolated points beyond the whiskers.

This study evaluated the performance of the RF, ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM models using box and whisker plots (Fig. 16). The RF model had a median accuracy of approximately 0.76 and a narrow interquartile range of 0.75–0.79, indicating consistent performance. Similarly, SVM had a median accuracy of 0.76 and a slightly narrower range of 0.74–0.77, reflecting stable results. The DT model achieved a median accuracy of about 0.85, spanning from 0.83 to 0.87, while AdaBoost had a slightly higher median of 0.86, with a similar range of 0.84–0.89. Notably, the ANN model outperformed the other models with a median accuracy of 0.87 and a span between 0.84 and 0.89. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that ANN and AdaBoost have superior median accuracy and consistency compared to the other models. In contrast, RF and SVM, while stable, have relatively lower accuracy.

Noise sensitivity

A noise sensitivity plot shows how the performance of an ML model degrades with increasing data noise. On this basis, noise refers to random or irrelevant data that may obscure the meaningful patterns the model is designed to learn. Hence, these plots are valuable tools for assessing a model’s robustness to noisy inputs.

Figure 17a–e show the uncertainty in noise sensitivity of RF, ANN, DT, AdaBoost, and SVM. The RF model had an initial accuracy of 0.89 at zero noise, which gradually decreased to 0.82 as the noise reached 0.1 (Fig. 17a). Similarly, the initial accuracy of 0.90 for ANN (Fig. 17b), DT (Fig. 17c), and AdaBoost (Fig. 17d) declines gradually to 0.82 under the same noise conditions. All four models exhibit smooth curves, indicating a gradual and consistent declining performance. However, SVM (Fig. 17e) had a low initial accuracy of 0.78, which decreased to 0.72 as the noise level reached 0.1. While SVM exhibits lower overall performance, its performance degrades more gradually, suggesting its higher resilience to noise. Therefore, while ANN, DT, and AdaBoost demonstrate superior initial accuracy, SVM is the most noise-tolerant model. Noise sensitivity plots provide crucial insight into how ML models respond to data imperfections. All models exhibited reduced accuracy with higher noise levels, although the rate and extent of decline vary. Therefore, model selection should consider the baseline accuracy and robustness to noise, depending on the application’s requirements.

Conclusion and future work

This research has demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating ML classification techniques with GIS to assess and predict pavement performance by using IRI values as a proxy for estimating the PCI. Using 1042 data points from flexible pavement segments of the Nizwa–Muscat highway in Oman, the analysis confirmed that ML algorithms, particularly RF, can classify pavement conditions with high accuracy. Integration with GIS facilitated spatial visualization of pavement performance, thus providing a practical and intuitive decision-support tool for road maintenance and planning. This approach enhanced infrastructure management by enabling data-driven, proactive strategies and reducing reliance on traditional, often costly, pavement distress surveys. Future research can expand this framework by incorporating larger and more diverse datasets from different regions and pavement types to improve model generalizability. Including variables, such as traffic loads, environmental conditions, and subgrade characteristics, could further enhance the model’s performance. It is possible to improve prediction robustness by exploring deep learning models and ensemble hybrid techniques. Furthermore, employing IoT-based sensors for real-time data acquisition with continuous integration into cloud-based GIS platforms could pave the way for a dynamic, real-time PMS. Finally, collaboration with local transportation agencies will be vital for validating the models in real-world settings and ensuring their long-term adoption and practical impact.

Data availability

The corresponding author in this research will be a responsible for providing these data.

References

Chang, C. M., Cheng, D., Smith, R. E., Tan, S. G. & Hossain, A. SMART quality control analysis of pavement condition data for pavement management applications. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtst.2024.06.007 (2024).

Milad, A., Ali, A. A. & Izzi Md Yusoff, N. Multi-classification machine learning algorithm for predicting pavement maintenance treatments. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control and Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS) 30–34 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/I2CACIS61270.2024.10649874.

Tamagusko, T. & Ferreira, A. Machine learning for prediction of the international roughness index on flexible pavements: A review, challenges, and future directions. Infrastructures (Basel) 8, 170 (2023).

Ali, A. A., Milad, A., Al-Sabaeei, A. M., Babalghaith, A. M. & Yusoff, N. I. M. Utilizing machine learning algorithms and regression techniques to develop pavement performance indices for dry freeze climate regions. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. (2025) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-025-01933-z.

Xi, L., Luo, R. & Liu, H. Effect of relative humidity on the linear viscoelastic properties of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 307, 124956 (2021).

Chen, W. & Zheng, M. Multi-objective optimization for pavement maintenance and rehabilitation decision-making: A critical review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 130, 103840 (2021).

Ali, A. A., Milad, A., ALMufargi, H. & Yusoff, N. I. Pavement deterioration modeling of the international roughness index based on fuzzy logic approach. J. Soft Comput. Civ. Eng. 9, 1–19 (2025).

ASTM D6433-23. Practice for roads and parking lots pavement condition index surveys. ASTM 1–3 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1520/D6433-23 (2023).

Imam, R., Murad, Y., Asi, I. & Shatnawi, A. Predicting pavement condition index from international roughness index using gene expression programming. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 6, 1–12 (2021).

Michels, D. J. Pavement condition index and cost of ownership analysis on preventative maintenance projects in Kentucky. (2017).

Kavianipour, O., Montazeri-Gh, M. & Moazamizadeh, M. Road profile measurement using the two degrees of freedom response-type mechanism. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 229, 1074–1087 (2015).

Albitres, C. M. C., Smith, R. E. & Pendleton, O. J. Comparison of automated pavement distress data collection procedures for local agencies in San Francisco Bay Area, California. Transp Res Rec 1990, 119–126 (2007).

Lee, S.-Y., Choi, J.-S. & Le Minh, T. H. Unraveling the optimal strategies for asphalt pavement longevity through preventive maintenance: A case study in South Korea. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03464 (2024).

Loprencipe, G., Pantuso, A. & Di Mascio, P. Sustainable pavement management system in urban areas considering the vehicle operating costs. Sustainability 9, 453 (2017).

Ahmed, N. G., Awda, G. J. & Saleh, S. E. Development of pavement condition index model for flexible pavement in Baghdad City. J. Eng. 14, 2120–2135 (2008).

Sayers, M. W. On the calculation of international roughness index from longitudinal road profile. Transp. Res. Rec. (1995).

Buttlar, W. & Islam, S. Integration of smart-phone-based pavement roughness data collection tool with asset management system. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272355273 (2014).

Chen, S.-L., Lin, C.-H., Tang, C.-W., Chu, L.-P. & Cheng, C.-K. Research on the international roughness index threshold of road rehabilitation in metropolitan areas: A case study in Taipei City. Sustainability 12, 10536 (2020).

Guerra, K., Raymundo, C., Silvera, M., Zapata, G. & Moguerza, J. M. Pothole detection and International Roughness Index (IRI) calculation using ATVs for road monitoring. Sci. Rep. 14, 19761 (2024).

Madanat, S. M., Nakat, Z. El & Sathaye, N. Development of empirical-mechanistic pavement performance models using data from the Washington State PMS database. (2005).

Perera, R. W. & Kohn, S. D. LTPP data analysis: Factors affecting pavement smoothness. (Transportation Research Board, National Research Council Washington, DC, 2001).

Wen, H. Design factors affecting the initial roughness of asphalt pavements. Int. J. Pav. Res. Technol. 4, 268 (2011).

Chandra, S., Sekhar, C. R., Bharti, A. K. & Kangadurai, B. Relationship between pavement roughness and distress parameters for Indian highways. J Transp Eng 139, 467–475 (2013).

Karballaeezadeh, N., Danial Mohammadzadeh, S., Mudabbiruddin, M. & Rad, A. H. Modeling road roughness through vibration analysis for driving quality and extended discussion on AI potential. In 2023 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI) 000045–000052 (IEEE, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/SACI58269.2023.10158586.

Mousa, E., El-Badawy, S. & Azam, A. Effect of reclaimed asphalt pavement in granular base layers on predicted pavement performance in Egypt. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 5, 57 (2020).

Piryonesi, S. M. & El-Diraby, T. E. Examining the relationship between two road performance indicators: Pavement condition index and international roughness index. Transp. Geotech. 26, 100441 (2021).

Siswoyo, D. P. & Setyawan, A. The evaluation of functional performance of national roadway using three types of pavement assessments methods. Procedia Eng. 171, 1435–1442 (2017).

Hettiarachchi, C., Yuan, J., Amirkhanian, S. & Xiao, F. Measurement of pavement unevenness and evaluation through the IRI parameter—An overview. Measurement 206, 112284 (2023).

Almubarok, F. S., Mudiyono, R. & Soedarsono, S. Road pavement condition index as a method to analyze the level of road damage. JACEE (J. Adv. Civ. Environ. Eng.) 5, 84–93 (2022).

Luo, Z. et al. Research on influencing factors of asphalt pavement International Roughness Index (IRI) based on ensemble learning. Intell. Transp. Infrastruct. 1, liac014 (2022).

Ali, A. A., Esekbi, M. I. & Sreh, M. M. Predicting pavement condition index using machine learning algorithms and conventional techniques. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 21, 304–309 (2022).

Ali, A. A., Milad, A., Hussein, A., MdYusoff, N. I. & Heneash, U. Predicting pavement condition index based on the utilization of machine learning techniques: A case study. J. Road Eng. 3, 266–278 (2023).

Park, K., Thomas, N. E. & Wayne Lee, K. Applicability of the international roughness index as a predictor of asphalt pavement condition. J Transp. Eng. 133, 706–709 (2007).

Arhin, S. A., Williams, L. N., Ribbiso, A. & Anderson, M. F. Predicting pavement condition index using international roughness index in a dense urban area. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 5, 10–17 (2015).

Elhadidy, A. A., El-Badawy, S. M. & Elbeltagi, E. E. A simplified pavement condition index regression model for pavement evaluation. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 22, 643–652 (2021).

Hasibuan, R. P. & Surbakti, M. S. Study of pavement condition index (PCI) relationship with international roughness index (IRI) on flexible pavement. In MATEC web of conferences vol. 258 03019 (EDP Sciences, 2019).

Ali, A. et al. Towards development of PCI and IRI models for road networks in the City of St. John’s. In International Airfield and Highway Pavements Conference 2019 335–342 (American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA, 2019).

Abed, M. S. Development of regression models for predicting pavement condition index from the international roughness index. J. Eng. 26, 81–94 (2020).

Ali, A., Dhasmana, H., Hossain, K. & Hussein, A. Modeling pavement performance indices in harsh climate regions. J. Transp.Eng. Part B: Pavements 147, (2021).

Tangga, A. A. et al. Utilising machine learning algorithms to predict the Marshall characteristics of asphalt pavement layers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 9, 381 (2024).

Alloghani, M., Al-Jumeily, D., Mustafina, J., Hussain, A. & Aljaaf, A. J. A Systematic review on supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms for data science. 3–21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22475-2_1.

Alnaqbi, A., Zeiada, W. & Al-Khateeb, G. G. Machine learning modeling of pavement performance and IRI prediction in flexible pavement. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 9, 385 (2024).

AL-Jarazi, R., Rahman, A., Aisd, C., Lixs, C. & Al-Huda, Z. Evaluation and prediction of interface fatigue performance between asphalt pavement layers: Application of supervised machine learning techniques. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 25: 2370551 (2024).

Chung, F. et al. Ensemble machine learning classification models for predicting pavement condition. Transp. Res. Record: J. Transp. Res. Board 2678, 216–224 (2024).

Pantha, B. R., Yatabe, R. & Bhandary, N. P. GIS-based highway maintenance prioritization model: an integrated approach for highway maintenance in Nepal mountains. J. Transp. Geogr. 18, 426–433 (2010).

Heyns, A., Banick, R. & Regmi, S. Roads development optimization for all-season service accessibility improvement in rural Nepal using a novel cost-time model and evolutionary algorithm. (2021).

Mallika, I. L., Ratnam, D. V., Raman, S. & Sivavaraprasad, G. Performance analysis of neural networks with IRI-2016 and IRI-2012 models over Indian low-latitude GPS stations. Astrophys. Space Sci. 365, 1–14 (2020).

Gong, H., Sun, Y., Shu, X. & Huang, B. Use of random forests regression for predicting IRI of asphalt pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 189, 890–897 (2018).

Pandit, W. H., Sharma, K. P., Sharma, N., Tomar, P. & Khan, S. International roughness index prediction using various machine learning techniques on flexible pavements. In Big Data Analytics in Intelligent IoT and Cyber-Physical Systems 209–235 (Springer, 2023).

Qiao, Y., Chen, S., Alinizzi, M., Alamaniotis, M. & Labi, S. Estimating IRI based on pavement distress type, density, and severity: Insights from machine learning techniques. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.05413 (2021).

Hoang, N.-D. & Nguyen, Q.-L. A novel method for asphalt pavement crack classification based on image processing and machine learning. Eng. Comput. 35, 487–498 (2019).

Nabipour, N. et al. Comparative analysis of machine learning models for prediction of remaining service life of flexible pavement. Mathematics 7, 1198 (2019).

Kırbaş, U. & Karaşahin, M. Performance models for hot mix asphalt pavements in urban roads. Constr. Build. Mater 116, 281–288 (2016).

Mohamed, A. G., Alqahtani, F. K., Ismail, E. R. & Nabawy, M. Synergizing GIS and genetic algorithms to enhance road management and fund allocation with a comprehensive case study approach. Sci. Rep. 15, 4634 (2025).

Elshaboury, N., Yamany, M. S., Labi, S. & Smadi, O. Enhancing local road pavement condition prediction using Bayesian-optimized ensemble machine learning and adaptive synthetic sampling technique. Int. J. Pav. Eng. 25, 2365957 (2024).

Syukri, M. et al. Applying geographic information systems (GIS) for data base district road pavement condition: A case study. In 2024 18th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems, Services, and Applications (TSSA) 1–5 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TSSA63730.2024.10864221.

Radwan, M. M., Mousa, A. & Zahran, E. M. M. Enhancing pavement sustainability: prediction of the pavement condition index in arid urban climates using the international roughness index. Sustainability 16, 3158 (2024).

Karimzadeh, S., Ghasemi, M., Matsuoka, M., Yagi, K. & Zulfikar, A. C. A deep learning model for road damage detection after an earthquake based on synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and field datasets. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 15, 5753–5765 (2022).

Slocum-Gori, S. L., Zumbo, B. D., Michalos, A. C. & Diener, E. A Note on the dimensionality of quality of life scales: An illustration with the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS). Soc. Indic. Res. 92, 489–496 (2009).

Abdelaty, A., Jeong, H. D. & Smadi, O. Barriers to implementing data-driven pavement treatment performance evaluation process. J. Transp. Eng. Part B: Pavem. 144, 4017022 (2018).

Milad, A. A. et al. Development of a hybrid machine learning model for asphalt pavement temperature prediction. IEEE Access 9, 158041–158056 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models based on Bayesian optimization. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 17, 26–40 (2019).

Al-Kindi, K. M. & Janizadeh, S. Machine learning and hyperparameters algorithms for identifying groundwater Aflaj potential mapping in semi-arid ecosystems using LiDAR, sentinel-2, GIS data, and analysis. Remote. Sens. (Basel) 14, 5425 (2022).

Abdolrasol, M. G. M. et al. Artificial neural networks based optimization techniques: A review. Electronics (Basel) 10, 2689 (2021).

Wang, R. AdaBoost for feature selection, classification and its relation with SVM: A review. Phys. Procedia 25, 800–807 (2012).

Taherkhani, A., Cosma, G. & McGinnity, T. M. AdaBoost-CNN: An adaptive boosting algorithm for convolutional neural networks to classify multi-class imbalanced datasets using transfer learning. Neurocomputing 404, 351–366 (2020).

Salcedo-Sanz, S., Rojo-Álvarez, J. L., Martínez-Ramón, M. & Camps-Valls, G. Support vector machines in engineering: An overview. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 4, 234–267 (2014).

Noble, W. S. What is a support vector machine?. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1565–1567 (2006).

Costa, V. G. & Pedreira, C. E. Recent advances in decision trees: an updated survey. Artif Intell Rev 56, 4765–4800 (2023).

Meng, Y. et al. Classification of tree species using point cloud features from terrestrial laser scanning. Forests 15, 2110 (2024).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Nguyen, H. T., Nguyen, L. T. & Sidorov, D. N. A robust approach for road pavement defects detection and classification. J. Comput. Eng. Math. 3, 40–52 (2016).

Boozary, P., Sheykhan, S., GhorbanTanhaei, H. & Magazzino, C. Enhancing customer retention with machine learning: A comparative analysis of ensemble models for accurate churn prediction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 5, 100331 (2025).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) should replace the ROC AUC as the standard metric for assessing binary classification. BioData Min. 16, 4 (2023).

Canbek, G., TaskayaTemizel, T. & Sagiroglu, S. PToPI: A comprehensive review, analysis, and knowledge representation of binary classification performance measures/metrics. SN Comput. Sci. 4, 13 (2022).

Scheer, J., Tomaškovičová, S. & Ingeman-Nielsen, T. Thaw settlement susceptibility mapping for roads on permafrost-Towards climate-resilient and cost-efficient infrastructure in the Arctic. Cold Reg. Sc.i Technol. 220, 104136 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM, AA, ZA, and KA were involved in the conception and design of the study. The preparation of materials was carried out by AM, AA, ZA, and KA. AM, AA, and KA conducted the data collection, analysis, and evaluation for this research. AM and KA undertook the critical review of the data. The initial draft of the manuscript was composed by AM and KA, with all authors providing feedback on earlier versions. Every author reviewed and gave their approval for the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milad, A., Ali, A.A., Al-Sulaimi, Z.S. et al. Utilizing spatial artificial intelligence to develop pavement performance indices: a case study. Sci Rep 15, 39603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23290-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23290-7