Abstract

Senegalia macrostachya is a multipurpose native shrub in West Africa that faces challenges in natural regeneration due to pests and overharvesting. This study evaluates seed germination and early seedling growth according to provenance, maturity stage, and the number of seeds in the fruit. Fruits were collected from four sites in two climate zones, considering two maturity stages (full and medium maturity) and four fruit types (containing 2 to 5 seeds). Seeds were weighed and their water content was measured before germination trials in alluvial sand and composite soil substrates. Germination was recorded every two days. Starting 65 days after sowing, seedling growth was measured biweekly over a period of 145 days. Data were analyzed using ANOVA. The weight of the seeds ranged from 0.27 ± 0.02 g to 0.45 ± 0.02 g and varied significantly (p < 0.001) between the provenances and between the types of fruit. Seeds with lower water content (6.93 ± 0.33%) exhibited the highest germination rates. Germination rates varied significantly (p < 0.001) according to substrate type, maturity stage, and number of seeds in the fruit. Seeds from mature fruits, from the Sissili provenance in the Sudanian zone, and 2-seeded fruits showed the highest mean germination rates (73 ± 15.45%, 73 ± 5.79%, and 90 ± 9.52%, respectively). At 145 days post-emergence, seedlings had reached a collar diameter of 6.93 mm and a height of 60.8 cm, with significant growth increases observed every two weeks (p< 0.001). Mature fruits, the fruits from Sissili provenance, and the 5-seeded fruits produced the most vigorous seedlings. The number of leaves and branches did not vary significantly among treatments within each study factor. Root biomass allocation was lower than above-ground biomass and did not differ significantly across treatments. These findings provide valuable insights for promoting the cultivation of Senegalia macrostachya through optimal seed selection in natural stands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the Sahel, forest resources play a crucial role in meeting the socioeconomic needs of people1. They provide both timber and non-timber forest products (NTFPs), notably food, traditional medicine, fuelwood, construction materials, and handicrafts2,3. However, climate change and increasing demographic pressure are degrading natural forests4,5 and contributing to the growing scarcity of these essential resources.

In this context, domestication and cultivation offer promising strategies to reverse the decline of wild woody plant species and improve their contribution to food security. Many edible wild fruit tree species have the potential to enhance the nutritional quality of local diets6. From an ecological standpoint, some of these species also contribute to soil restoration7,8. Senegalia macrostachya (Rchb. ex DC) Kyal. & Boatwr., an indigenous woody species in the Fabaceae family, exemplifies such a multipurpose species. All parts of this species are used by local populations for various purposes3,9. Common uses include household consumption and the sale of seeds5,10,11,12. Despite its significant utilitarian value, the seeds of S. macrostachya are still harvested from the wild. The populations of the species are threatened by the high infestation of their mature seeds by bruchid insects, namely Bruchidius silaceus and Caryedon furcatus, as well as wildfires and overharvesting12,13. Pest infestation, coupled with overharvesting, significantly reduces the natural regeneration capacities of the plant11,12. For sustainable resource management, it is important to evaluate the reproductive potential of this species to inform appropriate conservation strategies. Among these strategies, domestication and cultivation may be promising approaches to mitigate human pressure on wild stands and improve their yields. Domestication techniques developed for other species emphasize the importance of multiple influential factors such as climate, soil, water availability, thermal stress, seed pretreatments, provenance, and seed trait variation14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

For effective domestication and cultivation, it is essential to identify the main reproductive factors. These factors involve both the reproductive material and the environmental context in which the plants are grown. In the case of S. macrostachya, these determinants remain poorly documented. By testing the effects of provenance, fruit maturity stage, number of seeds in the fruit, and substrate type on seed germination and early seedling growth, this knowledge gap can be addressed. Seed provenance has a significant impact on seedling development and should be considered when selecting the most suitable sources for reproduction17,20,21. In terms of the physiological characteristics of seeds, the maturity stage of fruits is an important factor for seed germination16,19,23. Choosing the right substrate is an important step in ensuring successful seed germination and seedling growth15,16. Understanding these germination determinants is crucial for developing effective S. macrostachya cultivation practices, particularly since its natural regeneration is limited by pest infestations and overharvesting of mature fruits11,12. The study aims to identify the optimal provenance, maturity stage, and number of seeds in the fruit to achieve the best seed germination and early seedling growth of S. macrostachya.

Materials and methods

Seed collection area and experimental site

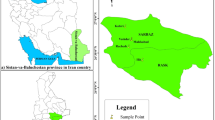

The fruits of Senegalia macrostachya were collected from four provinces in Burkina Faso, representing two distinct climate zones: Sudano-Sahelian zone (Passoré and Boulkiemdé) and Sudanian zone (Sissili and Tuy) (Fig. 1). The contrasting seasonal patterns and environmental conditions of these zones are described in Table 1. The experiments were conducted at the Centre National de Semences Forestières (CNSF), a forest seed research institute located in Ouagadougou, within the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone.

Location of the study area. Legend: The climate zones of the country were classified according to annual rainfall and thermal regimes24. Spatial data was obtained from the Geographical Institute of Burkina Faso (IGB). The map of the study area was processed using the ArcGIS Desktop version 10.8 software (http://www.esri.com).

Study species

Senegalia macrostachya is a thorny shrub species belonging to the Fabaceae family. Its natural distribution extends from Senegal to Chad. The species is relatively common and often forms gregarious populations in natural habitats. In Burkina Faso, it is evenly distributed across the three climate zones of the country25. Mature individuals generally reach heights of 2 to 4 m (Fig. 2) and have cracked bark covering the trunk. The leaves are alternate and bipinnate, bearing asymmetric pinnules and follicles. The inflorescence is terminal and multiflorous, consisting of elongated spike-shaped peduncles that bear numerous monoecious flowers. Flowering occurs from May to August, followed by fruiting beginning in July. The fruits are oblong pods that contain 2 to 8 seeds9, which mature and turn dry and reddish-brown by November.

All parts of S. macrostachya are used by people for various purposes3,9. The seeds are edible, rich in vitamins and proteins26,27, and are widely traded and consumed as food supplements. The bark and roots have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties28,29. In addition, the leaves are used in both human and veterinary medicine9.

Sampling design and data collection

Plant material of Senegalia macrostachya (Rchb. ex DC) Kyal. & Boatwr. (branches with leaves, pods, and flowers) was collected from the study areas for formal identification. The species was formally identified by Prof. Ouédraogo Amadé, a botanist and taxonomist at the Laboratory of Plant Biology and Ecology. A specimen was deposited in the OUA herbarium at the Université Joseph KI-ZERBO under the reference number Ouédraogo, A. 180 (OUA).

The fruits were randomly collected from all parts of the crown of healthy shrubs located 100 m apart from each other18,30,31. A total of 60 shrubs were sampled in two climate zones, with 30 shrubs per climate zone distributed equitably among four provinces. Within each province (provenance), fruits were harvested according to their maturity stage (mid-maturity and mature fruits) and their number of seeds in the fruit (2, 3, 4, or 5 seeds), which determines the morphology of the fruit. The three factors considered explanatory variables were provenance (4 treatments), maturity stage (2 treatments), and number of seeds in the fruit (4 treatments).

Fruits in the mid-maturity stage were harvested between November 1 and 15, 2022, while fully mature fruits were collected between December 1, 2022, and January 31, 2023. At each collection period, fruits containing 2, 3, 4, and 5 seeds were harvested separately. Manual harvesting was carried out using shears and poles. The fruits harvested in the mid-maturity stage were shade-dried in the laboratory. The seeds were manually extracted by splitting the fruits, followed by careful cleaning and sorting to ensure high seed quality. A total of 3,600 seeds were used in the study: 200 seeds were used to assess seed weight and moisture content, while the remaining 3,400 seeds were used for germination tests.

Experiment design

The biomass and moisture content of the seeds were determined following the protocol of the International Seed Testing Association31 using the oven-drying method. For each level of treatment, four replications of five seeds were used. The empty drying cups were first weighed using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.001 g. The seeds were then weighed to determine their initial fresh weight (M₀), placed in the cups, and dried in an oven at 103° C for 17 h. After drying, the cups were transferred to a desiccator for 45 min to allow the seeds to cool before measuring the final dry weight (M₁).

Three complete randomized block designs were implemented based on study factors, using alluvial sand and composite soil separately (Fig. 3). In the laboratory, 40 transparent plastic boxes were filled with moistened alluvial sand, previously sieved through a 3.75 mm sieve, and sterilized in an oven at 103° C for one hour. For each experimental factor, the design consisted of four replicates per treatment (Fig. 3a, b, c). In each box, 25 seeds were seeded on the seedbeds and lightly covered with a thin layer of dry sand before being closed with box lids. After sowing, the boxes were placed on the laboratory bench. Watering was performed as needed using droppers filled with tap water.

In the nursery, a completely randomized block design was used with four replicates per treatment. Black perforated polyethylene bags (30 cm high x 10 cm wide), filled with a substrate mixture of three parts soil, one part sand, and one part manure, served as germination pots. A total of 160 pots were used for the maturity stage factor (Fig. 3f). For the provenance of the fruit and the number of seeds in the fruit factors, 640 pots were used in total, with 320 pots allocated to each factor (Fig. 3d, e). Before sowing, the pots were watered for 48 h to thoroughly moisten the substrate. Then three seeds were sown in each pot at a depth of 1–2 cm. Daily watering was carried out between 8:00 and 9:00 am after sowing.

The number of germinated seeds was recorded every two days15,32. A seed was considered germinated when the stem emerged above the substrate. At 45 days after emergence, the seedlings were thinned to retain one per pot. Seedlings derived from the provenance of the fruit, the maturity stage, and the number of seeds in the fruit experiment were used to conduct three separate trials in a completely randomized block design. Each design, established in a greenhouse, included three replicates per treatment. A total of 450 seedlings were used, with 15 seedlings per treatment per replication.

At 65 days after sowing, when the seedlings had become lignified, the height of the stem and the diameter of the collar were measured using a ruler and a digital caliper with a precision of 0.01 mm. The number of leaves and branches was also counted. These measurements were repeated every two weeks over a period of 90 days. For biomass evaluation, three seedlings per treatment were dug up 65 days after sowing. The biomass of the fresh shoots and roots was weighed immediately after digging. Dry biomass was obtained by oven-drying the plant material at 103° C for 72 h.

Data analysis

The weight and water content of the seeds from each treatment were determined to evaluate their viability, using the ISTA32 method according to the following formulas: \(\:\text{B}\text{i}\text{o}\text{m}\text{a}\text{s}\text{s}\:\left(\text{g}\right)=({\sum\:}_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{m}}_{i})/\text{n}\); (1) where n is the total number of samples and mi is the mass of sample i. \(\:\text{M}\text{o}\text{i}\text{s}\text{t}\text{u}\text{r}\text{e}\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{t}\text{e}\text{n}\text{t}\:\left(\text{\%}\right)=\left(\right({\text{M}}_{0}-{\text{M}}_{1})/{\text{M}}_{0})\text{x}100\), (2) where: M0 is the initial seed mass before drying and M1 is the dry seed mass after oven drying. The germination rate was calculated using the following formula: \(\:\text{G}\:\left(\text{\%}\right)=(\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\:\text{g}\text{e}\text{r}\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{d}\:\text{s}\text{e}\text{e}\text{d}\text{s}/\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\:\text{s}\text{e}\text{e}\text{d}\text{s}\:\text{s}\text{o}\text{w}\text{n}\:)\text{x}100\) (3). Latency time (in days), defined as the time between the sowing date t0 and the first germination date t1, was calculated as: \(\:\text{L}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{n}\text{c}\text{y}\:\text{t}\text{i}\text{m}\text{e}\:=\:{\text{t}}_{1}-{\text{t}}_{0}\), (4). To evaluate the effect of the climate zone on seed biomass, moisture content, and germination rate, these variables were analyzed by climate zone. The following formulas were used to calculate mean growth parameters per treatment: \(\:\text{C}\text{o}\text{l}\text{l}\text{a}\text{r}\:\text{d}\text{i}\text{a}\text{m}\text{e}\text{t}\text{e}\text{r}\:\left(\text{m}\text{m}\right)=({\sum\:}_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{d}}_{i})/\text{n}\) (5), where n is the number of individuals and di is the stem diameter of individual i. \(\:\text{H}\text{e}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{t}\:\left(\text{c}\text{m}\right)=({\sum\:}_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{h}}_{i})/\text{n}\) (6), where n is the total number of individuals in the treatment and hi is the height of the individual i. \(\:\text{N}\text{u}\text{m}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{l}\text{e}\text{a}\text{v}\text{e}\text{s}=\left({\sum\:}_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{l}}_{i}\right)/\text{n}\) (7), where n is the total number of individuals of the treatment and li the number of leaves of individual i. \(\:\text{N}\text{u}\text{m}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{b}\text{r}\text{a}\text{n}\text{c}\text{h}\text{e}\text{s}=\left({\sum\:}_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{b}\text{r}}_{i}\right)/\text{n}\) (8), where n is the total number of individuals of the treatment and bri the number of branches of individual i.

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA at 5% significance level with R 4.3.2 software33. The interaction effects between the substrate and other factors (fruit provenance, maturity stage, and seed number in the fruit) on the germination rate were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. A Tukey post hoc test was applied to separate the means when the ANOVA was significant.

Results

Effects of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in the fruit on seed germination across substrate types

The biomass of the seeds ranged between 0.27 ± 0.02 g and 0.45 ± 0.02 g per seed. Their moisture content ranged between 6.20 ± 0.22% and 8.63 ± 0.71% (Table 2). No significant differences were found between maturity stages. Weights varied significantly between the provenances and between the number of seeds in the fruit. Seed water content of the Tuy provenance was significantly higher than that of the other provenances. It did not vary significantly between the number of seeds in the fruit. The standard error was low (Table 2) and showed that the weight and the seed water content of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in fruit factors were evenly distributed.

The latency time, which ranged from 4.00 ± 1.15 days to 8.00 ± 1.15 days, did not differ significantly between the treatments of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in fruit factors. S. macrostachya seeds germination rates ranged from 34 ± 5.16% to 90 ± 9.52% in the sand and from 15.00 ± 6.53% to 52.92 ± 21.82% in the composite soil. The germination rate of the mature seeds was significantly higher than that of the middle mature seeds in both types of substrates (Table 2). Germination rates did not show significant variation between climate zones (Table 2). The seeds of the 2-seeded fruits had the highest germination rate (p = 0.0078) both in the sand (90 ± 9.52%) and in the composite soil (52.92 ± 21.82%). The highest germination rates were observed in seeds from mature fruits, Sissili provenance, and those with low water content, and from 2-seeded fruits.

Substrate had a significant effect on the mean latency time of the seed germination of the provenances (p = 0.0054) and the types of fruit (p = 0.0182). Alluvial sand (53.5 ± 23.51%) had a significantly greater effect (p = 0.0116) on the seed germination rate compared to composite soil (25.0 ± 14.77%) for the maturity factor. The rate for all provenances was significantly (p < 0.001) higher in sand (66.00 ± 11.78%) than in composite soil (28.65 ± 11.90%). For the factor number of seeds in the fruit, the same trend of significance (p < 0.001) was observed with a higher germination rate in sand (76.50 ± 13.77%) than in composite soil (38.33 ± 17.89%).

The seed germination rate was exponential for the first 10 days after sowing in both the laboratory and the nursery for the maturity stage, provenance, and the number of seeds in fruit factors (Figs. 4a to f). In the sand, the mean germination time was 40 days for the mature seeds as well as for the Boulkiemdé and Sissili seeds (Fig. 4a, c). It was less than 20 days for the number of seeds in the fruit factor (Fig. 4e). In the composite soil, the mean germination time was 20 days after sowing (Figs. 4b, d, f).

Cumulative seed germination rates in alluvial sand and composite soil. Legend: (a) and (b) maturity stage; (c) and (d) provenances; (e) and (f) number of seeds in the fruit; Boul = Boulkiemdé and Pa = Passoré from the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone; Si = Sissili and Tuy = Tuy from the Sudanian climate zone.

Effect of maturity stage, provenance, and seed number of fruit on early seedling growth

The highest collar diameter values of the seedlings were recorded from mature fruit seeds (6.06 mm), the Sissili provenance in the Sudanian zone (6.93 mm), and from 5-seeded fruits (6.01 mm), corresponding to maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in fruit factors. In contrast, the seedlings of the middle mature fruits (2.85 mm), Boulkiemdé provenance of the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone (2.58 mm), and the 3-seeded fruits (2.6 mm) recorded the lowest values. The cumulative growth in the collar diameter was continuous for all seedlings of the different study factors. The growth trend was highly significant (p ˂ 0.001) between the measurement periods for each treatment of maturity stage, provenance, and seed number in the fruit (Fig. 5a, c, e).

The seedlings with the highest height values and the best growth performance were those of middle maturity fruit (60.8 cm), Sissili provenance (60.4 cm) from the Sudanian zone, and 5-seeded fruit (48.8 cm). The lowest seedling heights were observed for mature fruits (20.3 cm), Boulkiemdé in the Sudano-Sahelian zone (17 cm), and 4-seeded fruits (19.8 cm). The height growth across the different factors remained continuous and statistically significant (p˂ 0.001) between the measurement periods for 100 days, where the growth trend plateaued (Fig. 5b, d, f).

Effect of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in the fruit on the development of the seedling leaf and branch

The mean number of leaves per seedling 145 days after sowing was more than 10 and did not vary significantly between maturity stages (Fig. 6a). The first ramifications were observed in the mature fruit seedlings, which had more branches than the mid-mature fruit seedlings (Fig. 6b). The Boulkiemdé and Sissili provenances had the highest number of leaves compared to the Passoré and Tuy provenances (Fig. 6c). The number of branches was significantly (p = 0.012) higher in Tuy provenance seedlings than in other provenances (Fig. 6d). The number of leaves did not vary significantly with the number of seeds in the fruit seedlings (Fig. 6e). The seedlings of the 2-seeded fruits had the lowest number of branches compared to the seedlings from other fruit types. (Fig. 6f).

Biomass partitioning in seedlings according to maturity stage, provenances, and number of seeds in the fruit

The fresh and dry biomass aboveground was generally higher than that of the root (Fig. 7a, b, c). They showed no significant variation among maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in the fruit. The mature fruit seedlings had the highest mean value of fresh biomass (5.52 ± 1.96 g) compared to those of the middle mature (3.00 ± 1.48 g). Seedlings from Boulkiemdé provenance of the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone had the highest mean value of fresh biomass (3.79 ± 2.37 g), while those from Passoré in the same climate zone had the lowest value (3.27 ± 1.15 g). Regarding the number of seeds in the fruit, fresh biomass was highest (4.84 ± 2.49 g) in seedlings of 3-seeded fruits and lowest (2.75 ± 1.86 g) in 4-seeded fruits. No significant variation (P > 0.05) was observed in fresh and dry biomass between the different numbers of seeds in the fruit seedlings for all the measured parameters.

Biomass parameters of seedlings according to maturity stage, type, and provenance of fruits. Legend: BioMFT = total fresh biomass, BioMAF = ground biomass, BioMAS = dry ground biomass, BioMSF = fresh, BioMSS = dry underground biomass, RBf = fresh biomass ratio, BA = aboveground biomass, BS = underground biomass; Boul = Boulkiemdé and Pa = Passoré from the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone; Si = Sissili and Tuy = Tuy from the Sudanian climate zone.

Discussion

Influence of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in the fruit on Senegalia macrostachya seed biomass and moisture content

The seed biomass and moisture content are important factors in maintaining viability and germination capacities during seed storage15,34. The weight of the seed is more influenced by the provenance and type of fruit than by the stage of maturity of the fruit. The biomass of Senegalia macrostachya seeds varied significantly between provenances, corroborating the findings of Drabo et al.23. However, these authors also reported that the weight of 100 seeds of Senegalia macrostachya varied according to maturity stage. The weight of the seed was influenced by the annual rainfall. Regions with intermediate precipitation levels exhibited the highest seed weights, while both high-rainfall regions (Tuy) and low-rainfall regions (Passoré) recorded lower values. This suggests that S. macrostachya has an ecological preference for moderate rainfall for its seed biomass accumulation. The weight value also varied according to the size of the fruit in terms of the number of seeds in the fruit. An increase in pod size may lead to both higher seed weight and a greater number of seeds. Senegalia macrostachya seeds may exhibit a water tolerance threshold for biomass accumulation. Their tolerance to desiccation is reflected in the high germination rate observed even at a very low seed moisture content. This characteristic is typical of orthodox seeds35. These results are in line with those of Dadlani and Yadava35, who reported that orthodox seeds can maintain viability with moisture content as low as 5% without damage to the embryo. Senegalia macrostachya seeds can then be stored for a long period without losing their viability when other threats, such as bruchid insects, are removed. Coefficients of variation below 19% indicate a homogeneous distribution of seed moisture content values around the mean. A negative correlation was observed between seed water content and germination rate. Indeed, higher moisture content was associated with lower germination rates, and vice versa. This trend is opposite to the pattern observed in Carapa procera, for which seeds with higher moisture content exhibit the highest germination rate15. In Senegalia macrostachya, seed moisture content varied in parallel with regional rainfall patterns, increasing or decreasing accordingly. Indeed, seeds from the Sudanian climate zone, which receives the highest annual rainfall, exhibited the highest water content compared to those from the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone.

Seed germination performance according to maturity stage, provenances, number of seeds in the fruit, and substrate

Breaking seed dormancy is the first requirement for germination in the plant life cycle18,36. The results indicate that the seeds of Senegalia macrostachya should be harvested at full maturity to achieve a higher germination rate. Drabo et al.23 reported that mature seeds of S. macrostachya accumulate substantial amounts of proteins during late embryogenesis. This accumulation likely contributes positively to increasing the germination rate of mature seeds, unlike seeds from fruits of the mid-maturity stage, where protein deposition remains incomplete23. Similar findings have been reported by Murrinie et al.37 for Feronia limonia and by Adebisi et al.38 for Gmelina arborea, both of whom observed higher germination rates in fully mature seeds compared to those of the middle maturity stage. High seed moisture content inhibits germination rate. The physical maturity of the fruit is therefore a critical factor in ensuring the physiological maturity of the seeds, which ultimately determines seed quality and germination performance38. The results demonstrated that the seeds of fully mature fruits exhibit the highest germination performance. This suggests that seeds from fully mature fruits are physiologically developed and possess the necessary reserves and structural integrity to support successful germination. In contrast, earlier studies have shown that seeds in intermediate stages of maturity often lack sufficient nutrient reserves to sustain high germination rates39. Fully ripe seeds have accumulated the metabolic energy required for germination. This makes mature dried fruits the most suitable source for collecting Senegalia macrostachya seeds intended for seedling production. The rapid germination of Senegalia macrostachya seeds may be attributed to the absence of true dormancy imposed by the seed coat18. This trait confers an ecological advantage, as it allows seeds to germinate rapidly with the onset of the first rains, facilitating early seedling establishment and vigorous growth before the end of the rainy season14,18,40.

Increasing the weight of the seeds improves the germination rate, while the highest moisture content of the seeds reduces it. The contrasting effect of seed weight and water content on germination leads to the conclusion that organic and mineral substances are the main intrinsic determinants of germination. The higher cumulative germination rate in the Sudano-Sahelian climate zone than in the Sudanian climate zone could be explained by the better ability of the seeds to germinate in their environment of origin. Indeed, the experiments were carried out at a site in the Sudano-Sahelian zone. The high germination observed in the Sissili provenances could be related to intrinsic seed factors. The results of this study differed from those of Schelin et al.11 on Senegalia macrostachya, which reported higher germination rates after using different scarification and boiling pretreatments. This difference could be the effect of pretreatments that stimulated dormancy break and seed germination17,18,41,42.

The significantly high germination rate observed in seeds from 2-seeded fruits, both in the laboratory and the nursery, shows that this type of fruit provides seeds with a high germination capacity. According to Padonou et al.16, the morphotype and size of the seeds, similar to the number of seeds in the fruit, are considered important aspects of the reproductive strategy of the plant. These seeds are said to contain all physiological, genetic, and functional nutrients that are likely to induce the development of radicles and plumules. Sanogo et al.15 showed that sandy substrates significantly reduced germination time, but also contributed to lower germination rates in Carapa procera.

The results showed that all treatments had a higher germination rate in sand than in composite soil. Alluvial sand provides good aeration of sown seeds and favours their germination compared to composite soil in which seeds are less aerated. Sand is a very water-permeable and well-aired substrate, allowing good circulation of oxygen and water, which are essential for germination. The composite substrate appears to be heavy and compact, creating a kind of cement against seed emergence. Substrate porosity facilitates adequate aeration for the sown seeds, thereby enhancing their germination43,44,45. The work of Silue et al.46 on Khaya senegalensis confirms that sandy soils give the best results in terms of germination.

Effect of maturity stage, provenance, and number of seeds in the fruit on seedling growth

Seedling growth parameters such as height, collar diameter, number of leaves and branches, and ratio of aboveground to belowground biomass are important factors when assessing the quality and performance of seedlings intended for planting47,48,49. The initial kinetic growth in the collar diameter and height of Senegalia macrostachya seedlings was continuous.

The seeds of mature fruits stimulate the initial growth of the collar diameter, the number of leaves, and the number of branches. The mid-maturity seeds promoted height growth. Since weight and water content do not vary significantly between maturity stages, growth variations were related to phylogenetic traits acquired at each maturity stage. At mid-maturity, S. macrostachya seeds are rich in total carotenoids and chlorophylls, while during maturation these substances are degraded and the seeds accumulate abundant proteins from late embryogenesis23.

The origin of seeds can also be a source of variability in seedling growth parameters34. Seedlings whose seeds originated outside the experiment site (Sissili and Tuy in the Sudanian climate zone) showed the best growth performance in the Sudano-Sahelian zone. These results can be explained by the xerophytic nature of the species and its ability to adapt under harsh climate conditions of drought and high temperature17. The environment of each climate zone likely influenced the biological traits of the fruits and seeds of the species. The environmental conditions induced in each phytogeographic zone affected the fruits during their formation20.

Seedlings from 2 and 5-seeded fruits exhibited superior growth compared to others. Idohou et al.50 showed that seedling growth varied according to seed size50. The 2- and 5-seeded fruits of S. macrostachya would contain the most energetic and physiological resources to stimulate seedling growth. According to Abasse et al.34, the size of the fruit and seed and their nutrient content are positively correlated with the initial growth of the seedlings. There are several sources of variation in seedling growth according to morphotypes51. Morphological and physiological seed characteristics determine seedling vigour and survival52,53. The size and biomass of the seeds can determine the vigour of the seedling and the initial growth50,53. Depending on their nutrient or resource reserves and, as in 5-seeded fruit, large seeds would produce the most vigorous and long-lived seedlings53.

Although S. macrostachya seedlings can be transplanted to the real environment after three to four months of breeding in the nursery54, the values of the collar diameter, height, and leaf number parameters show that initial growth is relatively slow. This slow growth may be related to intrinsic factors of the species, such as deciduousness and shrubbery. In a greenhouse nursery, the growth of seedlings is influenced by several factors, including substrate, greenhouse size and spacing between seedlings, watering, and gradual leaching of substrate fertility55,56. Zida et al.49 had similar results, reporting that there were no significant differences in crown diameter and height values between 3-month and 6-month seedlings of S. macrostachya, and between 6-month and 9-month seedlings.

Biomass partitioning in Senegalia macrostachya seedlings

The partition of biomass between roots and aerial parts determines the development of seedlings57. The variation in biomass among factors would be explained by the weight of the seed and the water content. The initial seed reserves play an important role in the accumulation of nutrients by seedlings57. The almost proportional allocation of aboveground and belowground biomass could pose a risk to seedling survival during even mild drought. High levels of aboveground biomass indicate strong competition for light58. Several authors showed that when the environment is rich in nutrients and there is competition for light, the allocation of aboveground biomass is important57,59. Although root biomass first occurred, it was relatively low compared to aboveground biomass in most treatments of the study factors after 3 months of growth. Indeed, its allocation in seedlings changes over time and is influenced by environmental conditions57,60. At the provenance level, the accumulation of total seedling biomass and its distribution between roots and aerial parts are proportional to the seed weight. Similar results reported by Mašková and Herben57 showed that the distribution of seedling biomass varies with seed size.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the key factors influencing seed germination and early seedling growth of Senegalia macrostachya. The provenance and number of seeds in the fruit were the driving factors for seed germination capacity and early growth performance of the seedlings. The maturity stage of the fruit determines the germination rate. Senegalia macrostachya seeds germinated successfully without pretreatment under normal germination conditions. Sowing in a sand substrate increased the germination rate. The seeds of fully mature fruits with low water content exhibited the highest germination rates. Seeds from Sissili province, in the Sudanian climate zone, showed the highest germination rate and seedling growth performance. Seeds of 2-seed fruits had the highest germination rate, while seedlings of mature fruits and 5-seed fruits had the highest growth performance. Seedling growth and biomass partitioning were not influenced by the tested factors. These insights contribute to the optimization of Senegalia macrostachya cultivation and provide valuable seed selection guidance for conservation and sustainable management efforts to enhance its regeneration and resilience. The insights from this study represent progress toward the domestication and cultivation of Senegalia macrostachya. These findings guide the selection of fruits for optimal plant production.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sawadogo, Y., Ganaba, S., Tindano, E. & Some, A. N. Caractérisation des populations naturelles d’une légumineuse alimentaire sauvage, Senegalia macrostachya (Reichenb. Ex DC. Kyal & Boatwr) Dans Le secteur Nord-soudanien du Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 11, 2408. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v11i5.36 (2017).

Kouyaté, A. M., Van Damme, P. & Diawara, H. Évaluation de La production En fruits de Detarium microcarpum Guill. Perr Au Mali Fruits. 61, 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits:2006024 (2006).

Thiombiano, A. et al. Catalogue des Plantes vasculaires du Burkina Faso. Code Barre Boissiera. 65, 1–391 (2012).

Mouamfon, M. et al. Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth. Dans La forêt communautaire de payo (Est-Cameroun): inventaire, productivité et commercialisation. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 9, 200. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v9i1.18 (2015).

Ouédraogo, H., Kabré, B., Lankoandé, B., Lykke, A. M. & Ouédraogo, A. Impact of land use on the regeneration of Senegalia macrostachya in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Global Ecol. Conserv. 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03432 (2025).

Gaisberger, H. et al. Spatially explicit multi-threat assessment of food tree species in Burkina faso: A fine-scale approach. Plos One. 12, e0184457. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184457 (2017).

Finch-Savage, W. E. & Bassel, G. W. Seed vigour and crop establishment: extending performance beyond adaptation. J. Exp. Bot. 67 https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv490 (2016). 567 – 91.

Baatuuwie, B. N., Nasare, L. I., Smaila, A., Issifu, H. & Asante, W. J. Effect of seed pre-treatment And its duration on germination of Detarium microcarpum (Guill. And Perr). Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13, 317–323. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajest2019.2706 (2019).

Arbonnier, M. & Arbres arbustes et lianes des zones sèches d’Afrique de l’Ouest. (Editions Quae) (2019).

Ganaba, S. Le zamne, un mets très apprécié. In Echo de la recherche, Eureka n˚20-Publication Trimestrielle du CNRST, Burkina Faso, 10–11 (1997).

Schelin, M., Tigabu, M., Eriksson, I., Sawadogo, L. & Christer, O. N. P. Predispersal seed predation in Acacia macrostachya, its impact on seed viability, and germination responses to scarification and dry heat treatments. New Forest. 27, 251–267 (2004).

Yamkoulga, M., Waongo, A., Ilboudo, Z., Traoré, F. & Sanon, A. Effectiveness of hermetic storage using PICS bags and plastic jars for post-harvest preservation of Acacia macrostachya seeds. Adv. Entomol. 09, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.4236/ae.2021.91002 (2021).

Ouédraogo, P. et al. Uses and vulnerability of ligneous species exploited by local population of Northern Burkina Faso in their adaptation strategies to changing environments. Agric. Food Secur. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0090-z (2017). 6.

Ouédraogo, A. & Thiombiano, A. Regeneration pattern of four threatened tree species in Sudanian savannas of Burkina Faso. Agroforest Syst. 86, 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-012-9505-9 (2012).

Sanogo, S., Sacandé, M., Van Damme, P. & Ndiaye, I. Caractérisation, germination et conservation des graines de Carapa procera DC. (Meliaceae), Une espèce utile En santé Humaine et Animale. Biotechnol. Agronomie Société Et Environ. 17, 321–331 (2013).

Padonou, E. A. et al. Differences in germination capacity and seedling growth between different seed morphotypes of Afzelia Africana Sm. in Benin (West Africa). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 88, 679–684 (2013).

Bio Yandou, I., Soumana, I., Rabiou, H. & Mahamane, A. Effect of treatments on germination of Acacia tortilis subsp. Raddiana (Savi) Brenan in Niger, Sahel. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 13, 776–790. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v13i2.16 (2019).

Diawara, S., Zida, D., Dayamba, S. D., Savadogo, P. & Ouédraogo, A. Viability and germination capacities of Saba senegalensis (A. DC.) Pichon seeds, a multi-purpose agroforestry species in West Africa. Tropicultura 38, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.25518/2295-8010.1565 (2020).

Imorou, L. et al. Morphological variability of Euphorbia sepium N.E. Br. across the Sudanian and Sudano-Guinean zones of Benin Republic (West Africa): implications for conservation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromatic Plants. 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2022.100424 (2022).

Houénon, G. H. A., Fandy, H., Adomou, A. C. & Yédomonhan, H. Influence of morphological characteristics of fruits And provenances on seedling emergence And early growth in Detarium microcarpum Guill. & Perr. And Detarium Senegalense J.F. Gmel. (Fabaceae) in Benin. Heliyon 8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10945 (2022).

Kabré, B., Lankoandé, B., Zon, A. O., Ouédraogo, H. & Ouédraogo, A. Influence of fruit traits and seed provenance on the seed germination of Saba senegalensis (A. DC.) Pichon in Burkina Faso: implications for the domestication. Genet Resour Crop Evol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-024-02238-2

Kolawole, M. A. et al. Provenance and tree-to-tree differences in germination performance of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) delile: insights for domestication and selection. Heliyon 11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42279 (2025).

Drabo, M. S., Shumoy, H., Koala, J., Savadogo, A. & Raes, K. Ecological niche, genetic variation in natural populations, and harvest maturity of Senegalia macrostachya (Rchb. Ex DC) Kayl. & Boatwr., a promising wild and perennial edible-seeded crop. Agroforest Syst. 97, 1233–1247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-022-00772-5 (2022).

Dipama, J. M. Climate. In Biodiversity atlas of West Africa. (eds A. Thiombiano & D. Kampmann) 122–149, Ouagadougou & Frankfurt/Main. (2010).

Wittig, R., Schmidt, M. & Thiombiano, A. Cartes de distribution des espèces du genre acacia L. au Burkina Faso. Etudes Flore Végétation Burkina Faso. 8, 19–26 (2004).

Guissou, A. W., Parkouda, C., Ganaba, S. & Savadogo, A. Technology and biochemical changes associated with the production of zamne: A traditional food of Senegalia macrostachya seeds from Western Africa. J. Experimental Food Chem. 03, 131. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-0542.1000131 (2017).

Drabo, M. S. et al. Mapping the variability in physical, cooking, and nutritional properties of Zamnè, a wild food in Burkina Faso. Food Res. Int. 138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109810 (2020).

Ganamé, H. T. et al. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant and cytotoxic effects of Acacia macrostachya. Plants 10, 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10071353 (2021).

Zongo, A. W. S. et al. Senegalia macrostachya seed polysaccharides attenuate inflammation-induced intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in a Caco-2 and RAW264.7 macrophage co-culture model by inhibiting the NF-κB/MLCK pathway. Food Function. 5, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2fo02377f (2022).

Nafan, D., Silue, S. & Philips, S. E. Genetic variation of Saba senegalensis Pichon (Apocynaceae) and few nutritional values. Int. J. Biotechnol. Allied Fields. 1, 121–135 (2013).

Kabré, B., Lankoandé, B., Belem-Ouédraogo, M., Zon, A. O. & Ouédraogo, A. Predicting fruit production of Ziziphus Mauritiana Lam. According to phytogeographic zones in Burkina faso: implications for promoting the uses potentials and the sustainable management of the species. South. Afr. J. Bot. 147, 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2022.02.013 (2022).

International Seed Testing Associations Introduction to the ISTA rules. Int. Rules Seed Test. I-I-6 https://doi.org/10.15258/istarules.2023.I (2024).

RCore Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2024). https://www.R-project.org/

Abasse, T. et al. Morphological variation in Balanites aegyptiaca fruits and seeds within and among parkland agroforests in Eastern Niger. Agroforest Syst. 81, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-010-9323-x (2011).

Dadlani, M. & Yadava, D. K. Seed science and technology: Biology, Production, Quality. In seed science and technology. Springer Nat. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5888-5 (2023).

Simão, E. & Takaki, M. Effect of light and temperature on seed germination in Tibouchina mutabilis (Vell.) Cogn. (Melastomataceae). Biota Neotropica 8, 63–68. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032008000200006

Murrinie, E. D., Yudono, P., Purwantoro, A. & Sulistyaningsih, E. Effect of fruit age and post-harvest maturation storage on germination and seedling Vigor of wood Apple (Feronia limonia L. Swingle). Asian J. Agric. Biol. 7 (Special Issue), 196–204 (2019).

Adebisi, M. A., Abdul-Rafiu, A. M. & Ewuzie, C. O. The use of multiple seed vigour tests to predict field emergence and potential longevity in three capsicum species. Seed Sci. Biotechnol. 5, 25–26 (2011).

Neya, T., Daboue, E., Neya, O., Ouédraogo, I. & SenaK. Y. Tolérance à La dessiccation des semences de parinari curatellifolia planch. Ex benth, Vitex doniana sweet et Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides (lam) Watermann Au Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 11 (2730). https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v11i6.14 (2017).

Daws, M. I., Garwood, N. C. & Pritchard, H. W. Prediction of desiccation sensitivity in seeds of Woody species: A probabilistic model based on two seed traits and 104 species. Ann. Botany. 97, 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcl022 (2006).

Jaouadi, W., Hamrouni, L., Souayeh, N. & L Khouja, M. Étude de La germination des graines d’Acacia tortilis Sous différentes contraintes abiotiques. Biotechnol. Agronomie Société Et Environ. 14, 643–652 (2010).

Sina, A. K. S., Motou, B., Saley, K., Garba, A. & Mahamane, A. Suivi de La germination des graines et de La croissance de Acacia Senegal En pépinière: proposition pour Une amélioration de La production des plants Au Sahel. Afrique Sci. 17, 166–176 (2020).

Zerbo, P., Belem, B., Mllogo-Rasolodimby, J. & Damme, P. V. Short communication agronomy germination sexuée et croissance précoce d’Ozoroa insignis Del., Une espèce médicinale du Burkina Faso. Cameroon J. Experimental Biology. 6, 74–80 (2010).

Ouédraogo, A., Thiombiano, A., Hahn-Hadjali, K. & Guinko, S. Régénération sexuée de Boswelia dalzielii Hutch., Un Arbre médicinal de Grande Valeur Au Burkina Faso. Bois Et Forêts des. Tropiques. 289, 41–48 (2006).

Ado, A. et al. Effet de prétraitements, de substrats et de stress hydriques Sur La germination et La croissance initiale de Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. Eur. Sci. J. 13, 1857–7881. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n21p251 (2017). Ex A.DC.

Silue, P. A., Koffi, K. A. D., Koffi, A. B. & Kouassi, K. E. Essais de germination et suivi des performances de croissance des plants de Khaya senegalensis (Desv.) A. Juss., en zone soudanienne (Côte d’Ivoire). J. Anim. Plant Sci. 48, 8673–8685. https://doi.org/10.35759/janmplsci.v48-2.4 (2021).

Jacobs, D. F., Salifu, K. F. & Seifert, J. R. Relative contribution of initial root and shoot morphology in predicting field performance of hardwood seedlings. New Forest. 30, 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-005-5419-y (2005).

Grossnickle, S. C. Importance of root growth in overcoming planting stress. New Forest. 30, 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-004-8303-2 (2005).

Zida, D., Tigabu, M., Sawadogo, L. & Odén, P. C. Initial seedling morphological characteristics and field performance of two Sudanian savanna species in relation to nursery production period and watering regimes. For. Ecol. Manag. 255, 2151–2162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.12.029 (2008).

Idohou, R., Assogbadjo, A. E., Houehanou, T., Glèlè Kakaï, R. & Agbangla, C. Variation in Hyphaene Thebaica mart. Fruit: physical characteristics and factors affecting seed germination and seedling growth in Benin (West Africa). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 90, 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2015.11513185 (2015).

Salako, V. K. et al. Potential for domestication of Borassus aethiopum Mart., a wild multipurpose palm species in Sub-Saharan Africa. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 66, 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-019-00777-7 (2019).

Baskin, C. C. & Baskin, J. M. Seeds ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. 2nd edn. 1589 p. (Academic Press Inc., USA, 2014).

Goudégnon, E. O. A. et al. Effect of seed maturity and morphotype traits on seed germination of Lannea microcarpa in the dry Sudanian region of Benin. Bois Et Forêts Des. Tropiques. 352, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.19182/bft2022.352.a36925 (2022).

Zida, D. et al. Transplanted seedling age and watering effects on the field performance of Senegalia macrostachya (Rchb. Ex DC.) Kyal. & Boatwr., a high-valued Indigenous fruit tree species in Burkina Faso. Trees Forests People. 14 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2023.100461 (2023).

Wightman, K. E., Shear, T., Goldfarb, B. & Haggar, J. Nursery and field establishment techniques to improve seedling growth of three Costa Rican hardwoods. New Forest. 22, 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012020023446 (2001).

Aphalo, P. & Rikala, R. Field performance of silver-birch planting-stock grown at different spacing and in containers of different volume. New Forest. 25, 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022618810937 (2003).

Mašková, T. & Herben, T. Root:shoot ratio in developing seedlings: how seedlings change their allocation in response to seed mass and ambient nutrient supply. Ecol. Evol. 8, 7143–7150. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4238 (2018).

Kobe, R. K., Iyer, M. & Walters, M. B. Optimal partitioning theory revisited: nonstructural carbohydrates dominate root mass responses to nitrogen. Ecology 91, 166–179 (2010).

McCarthy, M. C. & Enquist, B. J. Consistency between an allometric approach and optimal partitioning theory in global patterns of plant biomass allocation. Funct. Ecol. 21, 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01276.x (2007).

Nadeem, M. et al. Maize seedling phosphorus nutrition: allocation of remobilized seed phosphorus reserves and external phosphorus uptake to seedling roots and shoots during early growth stages. Plant. Soil. 371, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1689-x (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to DANIDA for financing this study through CRES (Climate change Resilience of Ecosystem Services) project (20-13-GHA). They express their gratitude to Salamata Ouédraogo for her contribution to the data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by DANIDA through CRES (Climate change Resilience of Ecosystem Services) project (20-13-GHA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.O., B.K., A.M.L. and A.O. contributed to conceptualisation and methodology. H.O., and B.K. contributed to investigation, formal analysis and original writing. H.O., A.M.L., H.T.G., A.A.A., and B.L. contributed to structure, revision and editing. A.M.L., and A.O. contributed to critical revision and editing of the final version. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Approval for experiments and collection of plant material

Burkina Faso’s forestry code, under law no. 003-2011/AN, authorises the collection of plant specimens for research purposes in all climate zones. All farmers consented to the collection of fruit from their land. Forest officers consented to data collection in protected areas.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouédraogo, H., Kabré, B., Lykke, A.M. et al. Effect of provenance and traits of fruit on the seed germination of Senegalia macrostachya in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Sci Rep 15, 39709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23328-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23328-w