Abstract

There is conflicting evidence regarding the association between platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and the prediction of outcomes in bladder cancer (BCa). Due to the rapidly increasing availability of data to explore this issue, this updated meta-analysis investigates how pretreatment PLR influences the outcomes of BCa. Literature was retrieved from Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and PubMed from 2015 to April 2025. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and pooled hazard ratio (HR) have been employed in the exploration of the link across BCa prediction and PLR. The 95% CIs and pooled odds ratios (ORs) examined the connection between PLR and clinicopathological features of BCa. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression were conducted to identify the main sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the robustness of the results. The Egger’s test and “trim and fill” method have been used in evaluating publication bias. This study incorporated 20 studies comprising 5,594 participants. Elevated PLR was conspicuously linked to inferior overall survival (OS) (HR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.23–1.85, P < 0.001) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) (HR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.26–2.24, P < 0.001). A marginally significant association was observed between high PLR and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR = 1.61, 95% CI1.00–2.59, P = 0.052). No strong correlation between PLR and cancer-specific survival (CSS) (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.96–1.35, P = 0.138). Additionally, elevated PLR was significantly associated with tumor stage ≥ T2 (OR = 1.92, 95% CI 1.24–2.97, P = 0.003). The PLR can be regarded as an indicative predictor of the destitution of individuals suffering from BCa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bladder cancer (Bca) presents a type of malignant tumor occurring frequently, and whose elevated morbidity and mortality rates pose a significant healthcare burden1. Annually, it affects 600,000 people, with about 66% experiencing recurrence within five years2. During the early phase, Bca might not show any symptoms or may manifest as minor blood in the urine, which is often unnoticed by patients. At present, the most frequently employed technique for diagnosing Bca is the invasive cystoscopic biopsy3. Of all Bca, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)4 represents 75%, and its prognosis is significantly better than that of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), marking the timely diagnosis of Bca as a hallmark for halting this disease. NMIBC is treated with transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), then a risk-based intravesical therapy (IVe), achieving a 90% overall survival rate5. In contrast, MIBC is characterized by a high risk of progression, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes, often requiring radical cystectomy (RC) and systemic chemotherapy6. However, despite rigorous treatment, they still have a high recurrence rate, making long-term monitoring essential and early detection beneficial for improving prognosis7. Managing the prognosis of Bca continues to be a challenge for clinicians8. Therefore, a feasible instrument for making predictions and diagnoses is required.

Inflammation associated with cancer manifests in the cellular microenvironment surrounding the tumor and occupies a key position in prognosticating disease advancement and survival outcomes across various malignancies9. Systemic inflammation can be evaluated using blood biomarkers, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)10, Lymphocyte-C-reactive protein ratio (LCR)11, and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)12. These serum and tissue biomarkers, indicating systemic inflammatory response, are promising candidates for developing non-invasive immuno-oncology assays13. The PLR is determined by dividing the platelet count by the lymphocyte count.

Studies have revealed PLR’s predictive significance in solid tumors like Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma14, laryngeal, gastric15, and neuroendocrine neoplasms16. The link between PLR and BCa prognosis was initially revealed by a meta-analysis executed by Wang et al.17, however, its findings were constrained by the limited data. In the present study, we updated the evidence base by incorporating 12 additional articles comprising 2,291 more patients and by including progression-free survival as an outcome indicator, thereby strengthening the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

Methods

Study registration

This investigation has been carried out per the regulations of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)18, and it is registered in PROSPERO under the identifier CRD420251071198. The study protocol can be accessed upon reasonable request.

Literature search strategy

The literature was derived from Cochrane Library, Web of Science databases, PubMed, as well as Embase from 2015-April 2025. Bibliographies of incorporated studies were reviewed. The search strategies are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria covered these points: (1) research that included BCa diagnosis was confirmed through pathological analysis; (2) studies whose participants were categorized as elevated and diminished PLR strata; (3) research that provided precise cut-off values for PLR; (4) studies investigating studies that examined a link of PLR, overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), and progression-free survival (PFS); (5) studies that provided adequate information for determining the hazard ratio (HR) as well as 95% confidence intervals (CIs); (6) studies published in the English language. The exclusion criteria comprised: (1) reviews, editorials, conference abstracts without full text, letters, and case reports; (2) duplicate or overlapping cohorts; (3) studies not reporting OS, CSS, RFS, and PFS; (4) studies not providing sufficient data to obtain an effect size.

Data extraction

Two investigators (ZBN and YZY) independently selected the studies for this analysis. Discussions were carried out to resolve any disagreements until a consensus was reached. The following details have been derived from every research: first author, publication year, country, quantity of cases, age, thresholds, study design, study period, therapeutic approach, and survival results. Most HR parameters were extracted directly from the included publications. For studies that did not provide HR explicitly, we digitized the published Kaplan–Meier curves using Engauge Digitizer to extract time-survival coordinates, and individual patient data were subsequently reconstructed with the IPDfromKM algorithm to estimate HR19.We contacted the first and/or corresponding authors to acquire any missing information as necessary.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Considering that the nature of all included studies was retrospective, two reviewers (ZBN and YZY) independently assessed the methodological quality and potential risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) 20. The NOS is a semi-quantitative rating system that utilizes a star-based scale, with a total score ranging from 0 to 9 stars. It evaluates the quality of studies across three domains: selection (up to 4 stars), comparability (up to 2 stars), and outcome assessment (up to 3 stars). Studies achieving a score of 6 stars or more were considered high quality. Scoring discrepancies were reviewed and resolved by the corresponding author (ZZB).

Statistical analyses

Pooled HR for OS, CSS, RFS and PFS were computed for the evaluation of the link between PLR and predictive value among individuals exhibiting BCa. According to Barraclough et al.21, an HR greater than 1 indicates an increased risk of adverse outcome in the exposed group. To explore the link between PLR and clinical traits involving tumor stage and metastasis, OR with 95%CIs were employed. Chen et al.22 suggested that an OR below 1.68 represents a very small effect, values between 1.68 and 3.47 indicate a small effect, 3.47 to 6.71 reflect a moderate effect, and values above 6.71 correspond to a large effect. Furthermore, the Higgins’ I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test have been employed in determine heterogeneity across research; the findings denoted significant heterogeneity. Since the primary studies are inherently heterogeneous in their methodology, a random-effects model should be employed in all analyses23,24. To identify potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis (ethnicity, publication year, sample size, cut-off values, treatment) and meta-regression were conducted. In line with common practice in previous oncological meta-analyses, we adopted 200 cases as threshold for sample size stratification in order to assess the impact of study scale on heterogeneity25,26. The robustness of the results was examined through sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was estimated using funnel plot assessment, Egger’s test and “trim and fill” method. Statistical analyses were executed on Stata 14.0, and findings having two-tailed P < 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

Search outcomes

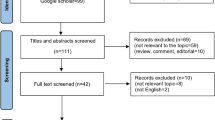

Figure 1 depicts a flowchart of the literature selection processes. The first database search resulted in 336 records and 189 studies after removing the duplicates. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 149 papers were dismissed, resulting in 40 full-text articles sought for retrieval. Of these, 39 were assessed for eligibility, with 27 subsequently excluded (Fig. 1). Ultimately, 20 studies27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 involving 5594 participants were considered for this analysis.

Baseline characteristics and patient demographics

Of the 20 retrospective cohort studies, published between 2015 and 2024, 8 studies were from China30,32,34,39,41,42,43,44, 5 from Turkey36,37,38,40,46, and 1 from Canada27, 2 from Korea28,35, 1 from UK29, 1 from Japan31, 1 from Poland33 and 1 from Iran45. Together, these studies included a total of 5594 patients (4684 males and 910 females), with median ages ranging from 61 to 75 years The threshold of PLR varied between 93 and 218. Table 1 portrays the initial features of the research covered.

Quality assessment of included studies

All 20 retrospective studies included in the analysis achieved NOS scores of six or above, suggesting a generally high methodological quality (Table 2).

Predictive importance of PLR for OS

A total of 13 articles were analyzed to evaluate the relationship between PLR and poor OS in individuals suffering from BCa. Unlike the previous investigation, this updated meta-analysis included data from six additional studies. As illustrated in Table 3 and Fig. 2A, the HR for high PLR was 1.51 (95% CI 1.23–1.85, P < 0.001), displaying a significant link. In addition, a considerable heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 84.5%, P < 0.001). When stratified by year of publication, a significant between-subgroup difference was detected (Pbetween = 0.019). Notably, the heterogeneity within studies published after 2020 markedly decreased (I2 = 13.1%), representing a reduction of 71.4 percentage points compared with the overall analysis, and this subgroup demonstrated a stronger effect size (HR 2.14 vs. 1.21). These findings suggest that publication year may partially account for the observed heterogeneity. In contrast, stratifications by ethnicity, sample size, cut-off value, and treatment did not reveal significant between-subgroup differences, and the heterogeneity within these subgroups remained high, indicating the presence of residual heterogeneity. Strata analyses also portrayed a significant association between high PLR and OS in patients receiving RC. Furthermore, the prognostic value of PLR for OS remained significant in subgroups of Caucasian patients and studies with a sample size of fewer than 200 participants (Table 3).

Predictive importance of PLR for CSS

For the association between PLR and CSS, we incorporated the 6 articles27,28,31,33,35,36. Despite the inclusion of additional literature, no significant association between PLR and CSS was observed. The relevant data can be found in Table 3 and Fig. 2B.

Predictive importance of PLR for RFS

Data from 9 articles27,30,36,39,40,42,43,44,46 were included in the examination of the link across PLR and RFS in participants with BCa. The pooled analysis suggested that PLR has a considerable prognostic impact on RFS, exhibiting HR = 1.68 (95% CI 1.26–2.24, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). Subgroup analyses and meta-regression indicated that ethnicity and cut-off value may contribute to the observed heterogeneity. However, it cannot be conclusively identified as the main source, as shown in Table 3.

Predictive importance of PLR for PFS

A total of 6 studies30,36,40,41,42,46 examined the relationship between PLR and PFS. The pooled analysis indicated a marginally significant association between elevated PLR and poorer PFS (HR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.00–2.59, P = 0.052). Notably, a significant association between PLR and PFS was identified in the subgroup of patients undergoing TURBT (HR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.21–2.99, P = 0.006). It is noteworthy that this subgroup analysis included only five studies, and thus the reliability of its findings may be limited. Detailed results are provided in Table 3 and Fig. 2D.

Relationship between PLR and clinical pathological factors

According to 8 studies29,30,33,34,38,41,44,45, there is a connection between PLR and clinicopathological factors like smoking status, chemotherapy, diabetes, age, distant metastasis, sex, tumor grade, tumor size, and tumor stage. Figure 3 and Table 4 demonstrate a significant link between high PLR and individuals aged ≥ 65 years (OR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.22–2.59, P = 0.003), as well as with tumor stage ≥ T2 (OR = 1.92, 95% CI 1.24–2.97, P = 0.003) and tumor size ≥ 3 cm (OR = 2.26, 95% CI 1.17–4.37, P = 0.016). However, PLR showed no correlation with sex (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.53–1.14, P = 0.135), tumor grade (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 0.62–2.35, P = 0.583), diabetes (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.60–1.60, P = 0.943), distant metastasis (OR = 1.03, 95% CI 0.48–2.21, P = 0.932), smoking status (OR = 1.38, 95% CI 0.44–4.34, P = 0.580), or chemotherapy (OR = 1.29, 95% CI 0.40–4.22, P = 0.672). In our analysis, the ORs for tumor stage, age, and tumor size were all within the range classified as small.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed leave-one-out sensitivity analyses. The sequential exclusion of each individual study did not result in notable changes in the pooled effect estimates, thereby supporting the stability and reliability of the results (Fig. 4).

Publication bias

As shown in Fig. 5, the two sides of the funnel plot appeared slightly asymmetric upon visual inspection. Therefore, we conducted Egger’s tests, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. The P values obtained were 0.002 for OS, 0.093 for RFS. Moreover, we applied “trim and fill” procedure and the results suggested that there were 3 potentially missing studies for the association PLR and OS (Supplementary Fig. 2). The adjusted pooled effect was HR = 1.30 (95% CI 1.08–1.57, P = 0.006), directionally consistent and remained statistically significant, but was attenuated relative to the unadjusted estimate.

Discussion

This updated meta-analysis analyzed 20 studies comprising 5594 BCa patients to determine the prognostic importance of PLR. Compared to the previous meta-analysis, our study incorporated an additional 12 articles encompassing 2291 patients, and further introduced PFS as an outcome measure. Concerning OS, despite the inclusion of a more extensive dataset, our findings replicated those of the previous meta-analysis, indicating that a high PLR is associated with inferior OS, consistent with previous study17. Regarding the correlation between PLR and age, we retained the data consistent with past investigations as well, suggesting that a high PLR is related to BCa patients aged ≥ 65 years. This finding may be attributed to the substantial remodeling and decline of the immune system that occurs with advancing age47. In addition, including more data enabled us to discover a statistically significant link between PLR and bad RFS. Moreover, elevated PLR was significantly correlated with higher tumor stage and increased tumor size, indicating its potential as a marker of tumor burden. Consequently, the serum PLR can function as a convenient and dependable biomarker for prognosing BCa.

The ability of PLR to predict bladder cancer may involve the following mechanisms: PLR is calculated by dividing the number of platelets by the number of lymphocytes, and it primarily involves these two types of blood cells. First, a substantial body of experimental evidence indicates that platelets are integral to various physiological and pathophysiological processes beyond their traditional role of maintaining hemostasis. Mechanistic investigations have identified the platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor P2Y12 as being indispensable for platelet aggregation within canine cancer models48. Additionally, platelets trigger Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) to foster cancer progression and invasiveness49. On the other hand, lymphocytes are widely recognized as indicators of systemic immune status, and their reduction serves as a hallmark of immunosuppression. A decreased lymphocyte count is closely linked to tumor immune evasion and unfavorable changes within the tumor immune microenvironment50. Taken together, PLR, as a composite inflammatory marker, reflects the balance between tumor-promoting and tumor-inhibiting immune mechanisms.

Previous investigations have demonstrated the prognostic value of PLR across diverse types of cancer. A comprehensive meta-analysis encompassing 49 studies entailing 28,929 participants suffering from gastric cancer demonstrated a considerable correlation between high levels of PLR and bad OS (P < 0.001) and DFS (P < 0.001)51. However, there is conflicting evidence regarding the association between PLR and the prediction of BCa. In this meta-analysis, we first found that elevated PLR levels serve as feasible predictive markers for both OS and RFS in adults with BCa. In addition, we observed a significant correlation between PLR and PFS in patients treated with TURBT (P < 0.001), which is consistent with the findings of Hu et al. 52. It should be noted that both the study by Hu et al. and the present analysis included only five studies; hence, the findings should be interpreted with caution. In contrast, no association was found between PLR and PFS among patients undergoing RC, which we attribute to the limited number of available studies in this subgroup. Lastly, this meta-analysis did not find that PLR predicted CSS in BCa. In summary, elevated PLR may indicate the need for more intensive and individualized therapeutic approaches.

Regarding heterogeneity, we prioritized the between-subgroups P value as the primary indicator to determine whether a stratification factor could explain the observed variability, while the extent of I2 reduction and improvements in within-subgroup homogeneity were considered as supporting evidence. For OS, the year of publication satisfied these criteria, whereas ethnicity and cut-off value in RFS showed only borderline trends. For CSS and PFS, certain subgroups demonstrated improved homogeneity; however, in the absence of significant between-subgroups P values, these observations should be interpreted as exploratory. Overall, the limited number of included studies and the uneven distribution of subgroups reduced the statistical power. Therefore, we interpreted these findings with caution and emphasized the need for further validation in future research.

Notably, our findings further suggest that in patients aged ≥ 65 years, with tumor stage ≥ T2, or with tumor size ≥ 3 cm, evaluation of the PLR may be particularly valuable for guiding treatment decisions and improving clinical outcomes. It is noteworthy that their OR were all within the small range. Our study also incorporated additional clinicopathological variables, including diabetes, smoking status and chemotherapy exposure. Although the associations between PLR and these factors did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.943, P = 0.580 and P = 0.672, respectively), their inclusion broadens the clinical context of the analysis and highlights potential directions for future investigations. As more data accumulate, these variables may emerge as significant modifiers of the prognostic value of PLR in BCa.

Finally, we acknowledge that this investigation has constraints. Firstly, ethnic groups in this research are relatively homogeneous, as all the participants were either from Caucasian or Asian backgrounds. Therefore, our conclusions are not generalizable to individuals of other ethnic groups. Second, all studies included in this analysis were retrospective, which inherently subjects the pooled results to selection bias, information bias, and confounding bias. Third, considerable heterogeneity was observed across studies, particularly in the analyses of OS and RFS (I2 > 60%). Although subgroup analysis and meta-regression were performed, the main source of heterogeneity in RFS could not be clearly identified. Forth, we chose the OR as the effect size for clinicopathological characteristics rather than the relative risk (RR). Several studies have noted that when the outcome is common, OR may appear larger than the corresponding RR53, thus potentially exaggerating the results. Therefore, caution is warranted in their interpretation. Lastly, in the OR results of PLR with age and tumor size, only four studies were included in each, which is fewer than five. Therefore, the reliability of these findings remains limited and requires further validation with additional studies. Future investigations are required to address these shortcomings.

Conclusion

In summary, this updated meta-analysis is the first to demonstrate that elevated PLR levels may serve as reliable predictive markers for both OS and RFS. Additionally, we first revealed that high PLR was significantly associated with advanced tumor stage and larger tumor size. This further confirms that PLR is a valuable prognostic tool for individuals suffering from BCa.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

van Hoogstraten, L. M. C. et al. Global trends in the epidemiology of bladder cancer: Challenges for public health and clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20(5), 287–304 (2023).

Ruggero, A., Clark, M., Lewkowski, A., Hurtado, R. & Tirado, C. A. Bladder cancer, a cytogenomic update. J. Assoc. Genet. Technol. 50(3), 114–126 (2024).

Dyrskjøt, L. et al. Bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 9(1), 58 (2023).

Claps, F. et al. BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Current treatment landscape and novel emerging molecular targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(16), 12596 (2023).

Lopez-Beltran, A., Cookson, M. S., Guercio, B. J. & Cheng, L. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 384, e076743 (2024).

Kamat, A. M. et al. Bladder cancer. Lancet 388(10061), 2796–2810 (2016).

Tomiyama, E., Fujita, K., Hashimoto, M., Uemura, H. & Nonomura, N. Urinary markers for bladder cancer diagnosis: A review of current status and future challenges. Int. J. Urol. 31(3), 208–219 (2024).

Tan, Z. et al. Comprehensive analysis of scRNA-Seq and bulk RNA-Seq reveals dynamic changes in the tumor immune microenvironment of bladder cancer and establishes a prognostic model. J. Transl. Med. 21(1), 223 (2023).

Asghar, M. S. et al. Inflammatory mediators as surrogates of malignancy. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 72(11), 2259–2263 (2022).

Cupp, M. A. et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 18(1), 360 (2020).

Yamamoto, T., Kawada, K. & Obama, K. Inflammation-related biomarkers for the prediction of prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(15), 8002 (2021).

Tang, X. et al. Diagnostic value of inflammatory factors in pathology of bladder cancer patients. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7, 575483 (2020).

Desponds, E. et al. immuno-transcriptomic profiling of blood and tumor tissue identifies gene signatures associated with immunotherapy response in metastatic bladder cancer. Cancers 16(2), 433 (2024).

Pawaskar, R. et al. Systematic review of preoperative prognostic biomarkers in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers 16(4), 698 (2024).

Skórzewska, M. et al. Systemic inflammatory response markers for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Cytokine 172, 156389 (2023).

Giannetta, E. et al. Are markers of systemic inflammatory response useful in the management of patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms?. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 672499 (2021).

Wang, X., Ni, X. & Tang, G. Prognostic role of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 9, 757 (2019).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 372, n71 (2021).

Liu, N., Zhou, Y. & Lee, J. J. IPDfromKM: reconstruct individual patient data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 21(1), 111 (2021).

Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M. & Tugwell, P. J. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Res. Inst. 2(1), 1–12 (2011).

Barraclough, H., Simms, L. & Govindan, R. Biostatistics primer: what a clinician ought to know: hazard ratios. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6(6), 978–982 (2011).

Chen, H., Cohen, P. & Chen, S. How big is a big odds ratio? interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 39(4), 860–864 (2010).

Al Khalaf, M. M., Thalib, L. & Doi, S. A. Combining heterogenous studies using the random-effects model is a mistake and leads to inconclusive meta-analyses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64(2), 119–123 (2011).

Zhai, C. & Guyatt, G. Fixed-effect and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Chin. Med. J. 137(1), 1–4 (2024).

Qian, S. et al. Is sCD163 a clinical significant prognostic value in cancers? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 10, 585297 (2020).

Wang, Y., Xu, C. & Zhang, Z. Prognostic value of pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with glioma: A meta-analysis. BMC Med. 21(1), 486 (2023).

Bhindi, B. et al. Identification of the best complete blood count-based predictors for bladder cancer outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Br J. Cancer. 114(2), 207–212 (2016).

Kang, M., Jeong, C. W., Kwak, C., Kim, H. H. & Ku, J. H. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio can significantly predict mortality outcomes in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Oncotarget 8(8), 12891–12901 (2017).

Lee, S. M., Russell, A. & Hellawell, G. Predictive value of pretreatment inflammation-based prognostic scores (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio) for invasive bladder carcinoma. Korean J. Urol. 56(11), 749–755 (2015).

Mao, S. Y. et al. Prognostic value of preoperative systemic inflammatory responses in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 10, 5799–5810 (2017).

Miyake, M. et al. Integrative assessment of pretreatment inflammation-, nutrition-, and muscle-based prognostic markers in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Oncology 93(4), 259–269 (2017).

Peng, D. et al. Prognostic significance of HALP (hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet) in patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 794 (2018).

Rajwa, P., Życzkowski, M., Paradysz, A., Bujak, K. & Bryniarski, P. Evaluation of the prognostic value of LMR, PLR, NLR, and dNLR in urothelial bladder cancer patients treated with radical cystectomy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22(10), 3027–3037 (2018).

Zhang, G. M. et al. Preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of overall survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Tumour Biol. 36(11), 8537–8543 (2015).

Yuk, H. D., Jeong, C. W., Kwak, C., Kim, H. H. & Ku, J. H. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients: initial intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin treatment after transurethral resection of bladder tumor setting. Front. Oncol. 8, 642 (2018).

Caglayan, A. & Horsanali, M. O. Can peripheral blood systemic immune response parameters predict oncological outcomes in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer?. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 26(5), 591–598 (2023).

Kayar, R. et al. Pan-immune-inflammation value as a prognostic tool for overall survival and disease-free survival in non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56(2), 509–518 (2024).

Karan, C. et al. Pretreatment PLR Is preferable to NLR and LMR as a predictor in locally advanced and metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 3(6), 706–715 (2023).

Wang, X., Zhang, S., Sun, Y., Cai, L. & Zhang, J. The prognostic significance of preoperative platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and interleukin-6 level in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 39(3), 255–264 (2024).

Avcı, M. A., Arslan, B., Arslan, O. & Özdemir, E. The role of thrombocyte/lymphocyte ratio and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (De Ritis) ratio in prediction of recurrence and progression in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cureus. 16(4), e59299 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Development of nomograms related to inflammatory biomarkers to estimate the prognosis of bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. Ann. Transl. Med. 9(18), 1440 (2021).

Wu, R. et al. Prognostic value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients: Intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin treatment after transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Front. Surg. 9, 907485 (2022).

Yi, X. et al. The relationship between inflammatory response markers and the prognosis of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and the development of a nomogram model. Front. Oncol. 13, 1189086 (2023).

Wang, C., Jin, W., Ma, X. & Dong, Z. The different predictive value of mean platelet volume-to-lymphocyte ratio for postoperative recurrence between non-muscular invasive bladder cancer patients treated with intravesical chemotherapy and intravesical chemohyperthermia. Front. Oncol. 12, 1101830 (2022).

Salari, A. et al. Prognostic value of NLR, PLR, SII, and dNLR in urothelial bladder cancer following radical cystectomy. Clin. Genitourin Cancer. 22(5), 102144 (2024).

Yilmaz İÖ, Değer M, Akdoğan N, Aridogan I, Bayazıt Y, Urooncology VIJTBo. Prognostic values of inflammatory markers in patients with high-grade lamina propria-invasive bladder cancer. 2024;48.

Müller, L., Di Benedetto, S. & Pawelec, G. The immune system and its dysregulation with aging. Subcell Biochem. 91, 21–43 (2019).

Bulla, S. C., Badial, P. R. & Bulla, C. Canine cancer cells activate platelets via the platelet P2Y12 receptor. J. Comp. Pathol. 192, 41–49 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. The critical role of platelet in cancer progression and metastasis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28(1), 385 (2023).

Paijens, S. T., Vledder, A., de Bruyn, M. & Nijman, H. W. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cell Mol Immunol. 18(4), 842–859 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in gastric cancer: An updated meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 18(1), 191 (2020).

Hu, W. et al. Elevated platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcomes in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 16, 1578069 (2025).

Ranganathan, P., Aggarwal, R. & Pramesh, C. S. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Odds versus risk. Perspect. Clin. Res. 6(4), 222–224 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZZ and YZ designed the research and edited and revised the article. BZ and ZY performed the data extraction. BZ, ZY and ZZ carried out the meta-analysis. BZ and ZY drafted the article. All authors approved the submitted and final versions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Yao, Z., Zhou, Z. et al. The serum platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of outcomes in bladder cancer patients: an updated meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 39502 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23334-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23334-y