Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects of removable prostheses on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), the effects of removable prostheses on chewing ability and the effects of prosthesis type (Removable partial denture RPD versus complete denture CD) and sociodemographic factors on both chewing ability and OHRQoL. Data from 90 participants were collected using a questionnaire. Chewing ability and OHRQoL were assessed before and after treatment through questionnaires. A two-tailed α of 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals were applied to identify statistically significant results in this survey. Differences between the RPD and CD treatment groups in terms of demographic variables (gender, age, income, education level, smoking status, medical history, and social connections) and previous denture experience were analysed using the Mann‒Whitney U test. Participants with RPD or CD demonstrated significant improvements in chewing ability and OHRQoL post-treatment (p < 0.05), except for females in the RPD group, who showed no significant changes. Compared with the CD group, the RPD group had significantly better chewing ability both before (p < 0.001) and after (p = 0.027) treatment. The RPD group also reported better outcomes in many aspects, including less jaw pain, greater comfort while eating, and improved denture stability (p < 0.05). Stepwise regression revealed that higher income and smoking were associated with better pre-treatment outcomes, whereas having multiple dentures and smoking predicted worse post-treatment chewing scores. Notably, higher post-treatment chewing scores were associated with improved OHRQoL. Both the RPD and CD groups reported improved chewing ability and OHRQoL, with RPD resulting in superior functional outcomes. Sociodemographic factors such as income, sex, age, and smoking habits influenced the results both before and after treatment. These findings highlight the importance of individualised patient assessment and support the clinical value of RPDs in partially edentulous patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Edentulism (total or partial) is an irreversible oral health condition and a public health concern due to its economic burden and its impact on general and oral health1. The perceptions of tooth loss may vary between individuals on the basis of their personal, cultural, and social beliefs; age; gender; socioeconomic status; and educational level2,3,4.

Tooth loss refers to the absence of one or more natural teeth caused by dental caries, periodontal disease, trauma, or congenital conditions5. It negatively impacts aesthetics, quality of life, and the patient’s ability to chew and speak confidently1. Factors such as attending dental appointments, healthcare systems, educational levels, income, and oral hygiene habits influence tooth loss2,3,4. The loss of chewing ability and the aesthetic effects of missing teeth are linked to nutritional difficulties and reduced social interaction, which further impair the psychological and functional well-being of those affected6,7. The consequences of tooth loss go beyond oral health, significantly affecting a person’s self-esteem, social life, and overall functioning4.

For partially edentulous patients, treatment options include fixed dental prostheses (FDPs), removable dental prostheses (RDPs), implant-supported fixed prostheses (ISFPs), and combined fixed-removable restorations (COMBs)8. Rehabilitation with removable prostheses, either complete or partial, is particularly concerned with replacing teeth and soft tissues9. It is suitable when fixed dental prostheses are not feasible due to factors such as insufficient supporting teeth, anatomical limitations, or financial constraints10,11.

Prosthodontic treatments are known to affect patients’ perceptions of their oral health status, which is generally characterised using the concept of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)12. OHRQoL is a measure of how oral health impacts an individual’s quality of life, encompassing factors such as comfort, functionality, social interaction, and psychological well-being13,14. The patient’s OHRQoL, which is treated with partial or complete dentures, is widely affected by the patient’s educational level, socio-economic status, medical conditions, and smoking habits15. This concept is crucial for healthcare providers, as it helps guide patient-centred care and tailor treatments to improve oral health9.

Patient satisfaction and quality of life are the main priorities when deciding prosthetic treatment options16,17. Patient satisfaction can vary significantly from clinician assessment, as patients often emphasize aspects such as social, psychological, and cost-effectiveness factors that could be more influential on patient satisfaction than clinical measures18.

Removable prostheses, including removable partial dentures (RPDs) and complete dentures (CDs), play an important role in restoring masticatory function in edentulous and partially edentulous patients. Tooth loss compromises chewing efficiency, which can negatively affect nutritional intake, digestion, and general health and well-being19. By replacing missing teeth, removable prostheses help restore a degree of functional ability, enabling patients to chew a wider variety of foods than they could manage without any prosthetic support. Although they are not as effective as natural dentition or implant-supported prostheses, removable dentures can still lead to significant improvements in masticatory efficiency and patient-reported chewing satisfaction20.

This study aimed to (I) investigate how removable prostheses affect oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL); (II) to explore their impact on chewing ability; and (III) to assess the effect of prosthesis type (RPD versus CD) and sociodemographic factors on both chewing ability and OHRQoL. The null hypotheses were: i) there is no difference in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) or chewing ability before and after treatment with removable prostheses. ii) There is no difference in OHRQoL or chewing ability between patients treated with removable partial dentures (RPD) and those treated with complete dentures (CD), either before or after treatment. iii) Sociodemographic factors do not influence chewing ability or OHRQoL, before or after treatment.

Methodology

Ethical approval

This is a cross-sectional analytical study that was conducted at the dental student clinics of the University of Jordan from February to June 2024. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board/Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan (Reference: 10/2024/10,673), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research process and objectives were explained to the participants, and written informed consent was signed by the participants. No personal information of patients was exposed or traced back to individuals, and the participants were assured of the confidentiality of the data.

Study design

This study was designed as a prospective observational study conducted in a dental students’ teaching clinic. Participants were not randomly assigned to treatment groups; however, the type of removable prosthesis—either a complete denture (CD) or a removable partial denture (RPD)—was determined based on each patient’s clinical condition (i.e., the presence of complete or partial edentulism) following standard diagnostic and treatment protocols. The primary objective was to assess changes in chewing ability and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) before and after prosthetic treatment and to explore how these outcomes were influenced by socio-demographic factors such as sex, employment status, and smoking habits.

Participants’ information

This study included patients who visited removable prosthodontics students’ clinics for the construction of complete or partial dentures from February to June 2024. Eligible participants were those who were partially or completely edentulous and needed tooth replacement with removable partial or complete dentures. Patients who visited clinics for check-ups only and who required further evaluation and needed more advanced treatment, or who had severe medical illness and mental retardation that might affect their ability to complete/understand the questionnaires or to cooperate with the investigator, were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire development

The study focused on patients’ experiences with removable partial dentures (RPDs) and complete dentures (CDs) before and after delivery. The data were collected with a self-administered questionnaire that was adapted from previously validated questionnaires commonly used in prosthodontic and oral health research8,21,22,23,24,25,26. These tools have been shown to reliably measure both chewing ability and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in denture wearers. The validation process included a comprehensive translation procedure, where the original English version of the questionnaire was translated into Arabic using the forward and back translation methods. Bilingual experts were involved to ensure linguistic accuracy and the preservation of conceptual meaning. In addition, the translated version underwent expert review by dental academic specialists to confirm its relevance, clarity, and cultural appropriateness. Patient-based assessments of denture satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) are naturally subjective and may be influenced by individual expectations, previous dental experiences, and cultural perceptions of oral health. Furthermore, social desirability bias and social bias can affect the accuracy of self-reported data, as participants may overstate or understate their satisfaction levels to align with perceived norms or expectations. To improve the validity and reliability of the findings, the study utilized structured questionnaires with clearly defined response categories and standardized scoring systems such as Likert scales.

The responses to certain questions were categorized using a frequency scale: Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, and Never. For questions related specifically to chewing ability, the responses were classified into three categories: “I have the ability,” “I have difficulty,” and “I don’t have the ability.” Chewing ability responses were scored using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 2. The total chewing satisfaction score was calculated by summing the scores of 10 individual items (Pickles, fresh fruits, dried fruits, meat and chicken, fish, nuts, sweets, cooked vegetables, bread and biscuits, and fresh vegetables), resulting in a possible total score ranging from 0 to 20. Similarly, responses to the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) questions were rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The total OHRQoL score was obtained by summing the scores of 9 individual items, yielding a total score ranging between 9 and 45. The 9 OHRQol were as follows: do you feel embarrassed because of missing teeth in your mouth; are you generally worried about your dental problems; do you have difficulty speaking or pronouncing certain letters?

Do you feel shy when talking to others; do you avoid leaving the house because of your dental issues; do you currently feel less tolerant or patient with your spouse or family members due to your dental condition; do you feel easily annoyed by other people; do you avoid being around others socially; and finally, do you feel less satisfied with life in general.

The study has two parts. The first part addresses demographic information and the personal characteristics of individuals. The demographic variables included age, sex, educational level, income, smoking status, job status, social interaction status and medical history.

The second part of the questionnaire includes functional and psychological questions to assess oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) and patient satisfaction. Data were gathered in two stages: Stage 1 (before delivery) and Stage 2 (after delivery). Stage 1 covered questions about problems caused by tooth loss, such as difficulty speaking and chewing, bad breath, anxiety due to tooth loss, self-esteem, confidence, and oral health care. It also addressed patients’ expectations and preferences when choosing dentures as a treatment option. These questions were repeated in Stage 2, along with evaluations of comfort, pain, and denture stability during eating and talking, to measure satisfaction levels and identify any changes in the patient’s experience after treatment.

Statistical analysis

For this survey, the SPSS software was used to perform the statistical analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics v20.0; IBM Corp., USA). Percentages and frequencies were employed to describe the categorical variables (demographic variables and responses for individual items). Continuous variables (total scores for OHRQoL satisfaction with chewing) were normally distributed based on the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test. Total scores for OHRQoL satisfaction with chewing were summarised using means, standard deviations, standard errors, 95% confidence intervals, medians, and ranges. A two-tailed α level of 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals were applied to determine statistically significant findings in this survey.

All comparisons between RPD and CD, recorded as categorical variables, were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Similarly, categorical variables representing before-and-after responses were tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Comparisons of continuous variables were analysed using the paired samples t-test and the independent samples t-test.

Stepwise regression analysis was conducted to predict the pre-treatment chewing and OHRQoL scores using demographic variables (age, sex, education level, income, smoking status, medical history, and social connection), previous RPD history, duration of previous RPD, type of arch, and the number of arches. Additionally, stepwise regression was performed to predict post-treatment chewing and OHRQoL scores based on demographic variables, prosthesis type, number of prostheses, and prosthesis position. Furthermore, separate regressions were conducted for each treatment group using the same prediction variables, with the addition of the Kennedy classification, number of modifications, and presence of prosthetic crowns when analysing the RPD group.

A priori power analysis via the G*Power computer software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich-Heine University) employed the linear multiple regression test of the F test family with a statistical power (1 – β) of 0.8, an effect size of 0.2, and a two-tailed α probability error of 0.05 to estimate the sample size for this survey. The total OHRQoL score was considered the primary outcome measure for this estimation. Consequently, the estimated sample size was 84 participants. Additional participants were included to guarantee the required sample size.

Results

Ninety-four participants were invited to take part in the study, and four declined (95.7% response rate). In total, ninety participants (36 females and 54 males) were included, and their data were analysed. Additionally, no participants were excluded during the study. The demographic details of the participants are presented for the entire sample as well as for each group (RPD group and CD group) in Table 1. Participants with CDs tended to be older, had lower incomes, were more likely to be non-workers or retired, practiced more smoking and less Hookah—“A traditional waterpipe device used for smoking tobacco or other substances, commonly known in other regions as shisha”, had more GIT disease, and reported better social connections than the RPD participants (p < 0.05, Table 1).

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for chewing scores and OHRQoL scores before and after treatment with RPD and CD prostheses within the study population. Participants showed improved chewing experience (i.e., higher chewing scores) and better OHRQoL (i.e., lower scores) following treatment with RPD or CD across the entire sample and its subgroups (p < 0.05, Table 3), except that females with RPD exhibited no significant differences in chewing scores (p = 0.751) or OHRQoL scores (p = 0.508) before and after RPD treatment (Table 3). Frequencies and percentages of responses to individual OHRQoL and chewing ability items before and after treatment with complete and removable partial dentures are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Table 4 presents a comparison between treatment groups (RPD and CD) as well as between sexes regarding chewing and OHRQoL scores before and after treatment. No significant differences between treatment groups or between genders were observed (p > 0.05, Table 4), except that participants with RPD treatment had better chewing experience than did participants with CD both before (p < 0.001, Table 4) and after (p = 0.027, Table 4) treatment.

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics for participants’ responses to the remaining survey items (31 items, including items regarding denture rating, problems, care, and usage) and gender and treatment group differences in this regard. Also, it presents the difference between before and after responses for some items. The participants with RPD reported more that they chose denture treatment out of conviction (p = 0.047), preferred other treatment over denture treatment (p = 0.010), felt less jaw pain after dentures (p < 0.001), were more comfortable eating with the dentures (p = 0.030), and had fewer food interruptions due to dentures (p = 0.009) than did the participants with CD (Table 5). Additionally, participants with RPD reported that their dentures were more stable during eating and talking (p < 0.001), had higher ratings of lower denture stability (p < 0.001), had higher ratings of the chewing mechanism in general (p = 0.006), cared more about their mouth (p = 0.035), and cleaned their dentures more frequently (p = 0.019) than did participants with CD (Table 5). Additionally, they reported less jaw pain after denture treatment. However, no significant sex differences were found in this regard, except that males reported sleeping more often with dentures than females did (p = 0.026, Table 5).

Additionally, Table 5 presents the difference between before and after responses for some items (bad breath and treatment preference, selection, concerns, and expectation). No significant differences were found in this regard (p > 0.05, Table 5).

Considering the entire sample, stepwise regression analysis revealed that having a higher income was associated with higher chewing scores before treatment (p = 0.020, Table 6). Additionally, being female (p = 0.002) and being a smoker (p = 0.017) were associated with better OHRQoL (lower OHRQoL scores) before treatment (Table 6).

In addition, stepwise regression analysis revealed that having more than one denture (p = 0.017) and being a smoker (p = 0.016) were associated with lower chewing scores after treatment (Table 6). Additionally, higher chewing scores after treatment were associated with better OHRQoL (lower OHRQoL scores) after treatment (p = 0.001, Table 6).

Considering the RPD treatment group alone, being female (p = 0.021) or older (p = 0.007) was associated with higher chewing scores before treatment (Table 6). Additionally, having a greater number of Kennedy modifications for a lower RPD was associated with higher OHRQoL scores (worse OHRQoL) after treatment (p = 0.020, Table 6).

Considering the CD treatment group alone, being a smoker was associated with lower OHRQoL scores (better OHRQoL) before treatment (p = 0.034, Table 6). Additionally, being a smoker (p 0.028) and having higher chewing scores after treatment (p < 0.001) were associated with lower OHRQoL scores (better OHRQoL) after treatment (Table 6).

Discussion

This study examined the effects of complete dentures (CD) and removable partial dentures (RPD) prostheses and evaluated the influence of prosthesis type and sociodemographic factors on both chewing satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in patients with partial or complete edentulism attending prosthodontic clinics. The results showed that treatment with removable partial dentures (RPD) or complete dentures (CD) resulted in significant improvements in both chewing ability and OHRQoL across the overall sample; hence, the first null hypothesis was rejected. Furthermore, significant differences were observed between the RPD and CD groups, with the RPD group having better chewing performance, denture stability, comfort, and fewer functional limitations, both before and after treatment; therefore, the second null hypothesis was rejected. Finally, sociodemographic factors such as income, sex, age, and smoking status significantly influenced chewing ability or OHRQoL, before or after treatment and the third null hypothesis was rejected accordingly.

The effects of CD and RPD on chewing ability and OHRQoL

The results revealed significant improvements in chewing satisfaction and OHRQoL scores after treatment with either CD or RPD. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating that prosthodontic interventions improve masticatory efficiency and oral comfort, which in turn enhances OHRQoL, with a close relationship between masticatory performance and OHRQoL12,24,27. Female participants with RPD showed no significant improvement in these scores, which can be attributed to sex-related differences in treatment outcomes10. Furthermore, psychosocial factors, including higher aesthetic expectations and variations in chewing patterns between sexes, could also explain this finding28. The results indicated a greater improvement in OHRQoL in both groups, which suggests that edentulous patients gain social and psychological benefits after prosthetic treatment1. Thus, they can engage more socially and have better self-esteem1. Nonetheless, in females, RPD did not significantly enhance chewing function or OHRQoL, although their functional outcomes are similar. This may be due to females being more self-conscious28, suggesting that women’s prosthetic satisfaction is influenced more by a mix of physiological, psychological, and social factors than by functional factors29.

Comparisons between treatment groups (RPD and CD) and sexes regarding chewing and OHRQoL scores before and after treatment. No significant differences between treatment groups or sexes were observed, which is in line with the findings of similar studies10,30. However, participants treated with RPD generally reported better chewing satisfaction than did those with CD, both before and after treatment. The OHRQoL of partial denture wearers was greater than that of complete denture wearers11. Tooth loss is associated with unfavorable OHRQoL scores, independent of study location31. The natural teeth in removable partial dentures (RPDs) maintain masticatory function by preserving periodontal proprioception and improving occlusal stability, whereas those in complete dentures (CDs) rely on mucosal support and thus have a less efficient force distribution32. One study reported the functional advantage of RPDs, particularly in terms of chewing ability, speech, and ease of adaptation10. Additionally, the presence of abutment teeth also contributes to better denture retention and patient satisfaction33. Although patients generally adapt to both types of prostheses over time, routine dental follow-up visits remain essential for the early detection and management of oral health issues, especially given the reactive dental-seeking behavior observed among many denture wearers11,34.

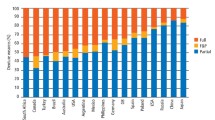

Lifestyle and sociodemographic aspects

Low socioeconomic status is associated with decreased oral health-related quality of life and a higher prevalence of edentulism due to limited access to dental care. Conversely, higher income correlates with improved chewing scores before treatment, possibly reflecting better access to dental care and preventive services among individuals with higher income2,3,28. These results revealed that lower-income individuals were more likely to receive CD rather than RPD, which is a pattern already encountered in several investigations on socioeconomic issues accompanying edentulism and the provision of dentures2.

Employment status was significantly associated with the type of prosthesis used, with a higher proportion of unemployed patients receiving complete dentures (P = 0.029). Although the clinical indication for complete or partial dentures is primarily based on the extent of edentulism, this relationship may be influenced by socioeconomic status, which affects oral health outcomes. Patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may experience higher rates of complete tooth loss due to limited access to dental care, thus increasing their need for complete dentures as a treatment option2,3,28.

Age was found to be a significant factor influencing prosthesis choice, with complete denture (CD) users being predominantly older (60–80 years), whereas removable partial denture (RPD) users were in the younger age group of 40–60 years (P = 0.006). Age is the most important determinant of the number of healthy teeth in adulthood2. Older patients are more likely to experience total tooth loss, thus requiring complete dentures as the primary prosthetic option. The age effect can be explained by the fact that the number of missing teeth increases with age, and the chances of using a complete denture increase35,36.

Educational level was also associated with prosthesis type, as a higher educational level was associated with a preference for fixed dentures. On the other hand, a lower educational level is associated with low oral health literacy and poor access to oral health1, which leads to a higher prevalence of complete denture use and objectively lower chewing efficiency and OHRQoL.

OHRQoL was also found to be affected by smoking status; smokers in the CD group had higher OHRQoL before treatment, whereas the general population had lower chewing scores after treatment. This paradoxical conclusion may be linked to how tobacco use alters sensory perceptions and how smokers adapt to mouth discomfort. Since smoking patients’ chewing performance declined after treatment (p = 0.017) and their OHRQoL results were poor, smoking was considered a significant factor in treatment outcomes37. Smoking damages the health of soft tissues, leading to xerostomia and subsequent pain and discomfort that hinder chewing ability38.

These findings indicate that the majority of denture wearers have limited knowledge concerning appropriate denture hygiene and maintenance practices. Even though male and female participants exhibited comparable outcomes in most domains, males were significantly more likely to sleep with their dentures—a behavior that has been consistently associated with poor oral hygiene and an increased risk of denture-related stomatitis. These findings underscore the necessity for targeted educational programs that consider gender-specific behaviours and preferences to promote optimal denture care and oral health outcomes39.

In addition, the proportion of participants who reported having halitosis decreased from 18.9% pre-treatment to 15.6% post-treatment. This decrease may indicate marginal clinical improvement, even though it did not approach statistical significance. Significantly, gastrointestinal disturbances were significantly more prevalent among complete denture (CD) users (P = 0.038). Loss of teeth can impair masticatory function, which can adversely impact dietary intake and lead to systemic conditions, including gastrointestinal disorders. These findings underscore the fundamental connection between oral and general health, emphasizing that the loss of functional dentition may have far-reaching implications for overall well-being40,41.

Patient satisfaction and stability of prostheses

Patient satisfaction is one of the most crucial determinants of prosthetic success. In this study, compared with CD users, RPD users felt more comfortable, had better denture retention, and had less jaw discomfort10,30. Additionally, RPD wearers demonstrated greater care in cleaning and maintaining their dentures (p = 0.019), which is consistent with the increased usability and comfort of RPDs10.

Stepwise regression analysis revealed that factors such as the number and position of prostheses and smoking status significantly influenced posttreatment chewing and OHRQoL scores. Specifically, having more than one denture and being a smoker were associated with poorer outcomes, likely due to the increased complexity of treatment and the adverse effects of smoking on oral tissues. Additionally, the presence of multiple Kennedy modifications was linked to OHRQoL in the RPD group, underscoring the challenges of rehabilitating patients with extensive dental arch defects, which is in line with the findings of similar studies10,42.

Patient attitudes toward denture treatment: balancing conviction, concerns, and expectations

The study results revealed that patients’ preferences and concerns regarding denture treatment were not statistically significant. No differences in participants’ selection of other treatment options as opposed to dentures were observed when patient preferences were compared before and after treatment. In addition, concerns regarding the selection of dentures as a treatment option were not significantly different when compared before and after treatment. This reflects a general level of satisfaction among denture patients30. The expectation regarding dentures changing lives remained stable, with 58.9% of participants expecting a positive impact pre-treatment and slightly increasing to 60.0% post-treatment. This finding aligns with the fact that psychological factors are considered significant factors influencing denture satisfaction43.

Strengths and limitations

This study offers a meaningful comparison between removable partial dentures (RPDs) and complete dentures (CDs), looking beyond clinical performance to consider how patients experience these treatments. The presence of some natural teeth probably improves stability and comfort, which is why patients with RPDs typically report better chewing performance and an enhanced quality of life related to oral health. This study offers a more accurate and comprehensive picture of the variables influencing denture performance by considering factors such as income, occupation, smoking habits, and general lifestyle.

There are, however, several limitations. The short follow-up period does not reveal how well people adapt to their dentures in the long term. Further, this study did not account for the type of material used in the fabrication of removable prostheses, which may influence patient comfort, function, and satisfaction.” However, it is recommended to investigate the impact of different prosthesis materials, such as cobalt-chromium, acrylic, Valplast, and PEEK, on patient-reported outcomes, including chewing ability and oral health-related quality of life, in future studies.

One of the limitations is the inclusion and pooling of diverse patient groups with various classifications of partial tooth loss without differentiating between them. Further, new denture wearers may experience more severe problems compared to experienced denture users. Nevertheless, these factors were not analysed in the present study, as they were considered beyond the scope of this study, which compares complete dentures to partial dentures. Although the chewing and OHRQoL scales were validated through a comprehensive translation process, formal validation for the specific cultural and linguistic context of this study was not conducted, which is also considered a limitation due to differences in values, traditions, and economic conditions in the population.

These findings are highly applicable to dental professionals. When possible, preserving natural teeth and offering RPDs would lead to better outcomes for patients. It is also obvious that preparing patients with practical expectations, encouraging good oral hygiene, and supporting healthier lifestyle choices, such as quitting smoking, could improve patient satisfaction with treatment.

From a broader perspective, this study emphasizes the need to make high-quality prosthetic care more accessible, especially for those with limited resources. Future studies should compare implant overdentures to traditional dentures and examine patient adaptation over time. In addition, understanding the psychological and gender-based factors that influence how people adjust to and feel about their prostheses would also be valuable.

Conclusions

Both the RPD and CD groups reported improved chewing ability and OHRQoL, with RPD resulting in superior functional outcomes. Sociodemographic factors such as income, sex, age, and smoking habits influenced the results both before and after treatment. These findings highlight the importance of individualized patient assessment and support the clinical value of RPDs in partially edentulous patients.

Data availability

The data included in this study are available upon request.

References

Rodrigues, A., Dhanania, S. & Rodrigues, R. “If I have teeth, I can smile.” Experiences with tooth loss and the use of a removable dental prosthesis among people who are partially and completely edentulous in Karnataka. India. BDJ Open 7(1), 34 (2021).

Donaldson, A. et al. The effects of social class and dental attendance on oral health. J. Dent. Res. 87, 60–64 (2008).

Cunha-Cruz, J., Hujoel, P. P. & Nadanovsky, P. Secular trends in socio-economic disparities in edentulism: USA, 1972–2001. J. Dent. Res. 86(2), 131–136 (2007).

Hashmat, S. et al. Relationship between lifestyle and oral health. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 522 (2023).

Haworth, S. et al. Tooth loss is a complex measure of oral disease: Determinants and methodological considerations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 46(6), 555–562 (2018).

Batista, M. J., Lawrence, H. P. & de Sousa, M. D. L. R. Impact of tooth loss related to number and position on oral health quality of life among adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 12(1), 1–10 (2014).

Gerritsen, A. E. et al. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 8(1), 126 (2010).

Swelem, A. A. et al. Oral health-related quality of life in partially edentulous patients treated with removable, fixed, fixed-removable, and implant-supported prostheses. Int. J. Prosthodont 27(4), 338–347 (2014).

Kavita, K. et al. Factors affecting patient satisfaction among patients undergone removable prosthodontic rehabilitation. J. Family Med. Prim Care 9(7), 3544–3548 (2020).

Awawdeh, M. et al. A systematic review of patient satisfaction with removable partial dentures (RPDs). Cureus 16(1), e51793 (2024).

Tosun, B. & Uysal, N. Examination of oral health quality of life and patient satisfaction in removable denture wearers with OHIP-14 scale and visual analog scale: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 24(1), 1353 (2024).

Komagamine, Y. et al. Association between self-assessment of complete dentures and oral health-related quality of life. J Oral Rehabil 39(11), 847–857 (2012).

Sischo, L. & Broder, H. L. Oral health-related quality of life: What, why, how, and future implications. J. Dent. Res. 90(11), 1264–1270 (2011).

Manfredini, M. et al. Oral health-related quality of life in implant-supported rehabilitations: A prospective single-center observational cohort study. BMC Oral Health 24(1), 531 (2024).

Tariq, S. et al. Impact of complete dentures treatment on Oral health-related quality of Life (OHRQoL) in edentulous patients: A descriptive case series study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 40(9), 2130–2135 (2024).

Elsyad, M., Altonbary, G. & Askar, O. Patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of conventional denture, fixed prosthesis and milled bar overdenture for All-on-4 implant rehabilitation. A crossover study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 11, 1107–1117 (2019).

Epifania, E. et al. Evaluation of satisfaction perceived by prosthetic patients compared to clinical and technical variables. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 8(3), 252–258 (2018).

Wang, Y., Liu, C. & Wang, P. Patient satisfaction impact indicators from a psychosocial perspective. Front Public Health 11, 1103819 (2023).

Ikebe, K. et al. Association of masticatory performance with age, posterior occlusal contacts, occlusal force, and salivary flow in older adults. Int. J. Prosthodont 19(5), 475–481 (2006).

Awad, M. A. et al. Oral health status and treatment satisfaction with mandibular implant overdentures and conventional dentures: A randomized clinical trial in a senior population. Int. J. Prosthodont 16(4), 390–396 (2003).

Aljabri, M. K., Ibrahim, T. O. & Sharka, R. M. Removable partial dentures: Patient satisfaction and complaints in Makkah City. KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 12(6), 561–564 (2017).

Mamdouh, R., Nader El-sherbini, N. & Mady, Y. Treatment outcomes based on patient’s oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) after receiving conventional clasp or precision attachment removable partial dentures in distal extension cases: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Brazilian Dental Sci. 22, 528–537 (2019).

Shaghaghian, S. et al. Oral health-related quality of life of removable partial denture wearers and related factors. J Oral Rehabil 42(1), 40–48 (2015).

Yamamoto, S. & Shiga, H. Masticatory performance and oral health-related quality of life before and after complete denture treatment. J. Prosthodont Res 62(3), 370–374 (2018).

Berniyanti, T. et al. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) analysis in partially edentulous patients with and without denture therapy. Clin. Cosmet Investig Dent 15, 89–98 (2023).

Hsu, K. J. et al. Relationship between remaining teeth and self-rated chewing ability among population aged 45 years or older in Kaohsiung City. Taiwan. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 27(10), 457–465 (2011).

Miranda, S. B. et al. Relationship between masticatory function impairment and oral health-related quality of life of edentulous patients: an interventional study. J. Prosthodont 28(6), 634–642 (2019).

Al-Omiri, M. K. et al. Relationship between impacts of removable prosthodontic rehabilitation on daily living, satisfaction and personality profiles. J. Dent. 42(3), 366–372 (2014).

Krausch-Hofmann, S. et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with removable denture renewal: A pilot study. J. Prosthodont 27(6), 509–516 (2018).

Čelebić, A. & Knezović-Zlatarić, D. A comparison of Patient’s satisfaction between complete and partial removable denture wearers. J. Dentistry. 31(7), 445–451 (2003).

Gerritsen, A. E. et al. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 8, 126 (2010).

Lopez-Cordon, M. A., Khoury-Ribas, L., Rovira-Lastra, B., Ayuso-Montero, R. & Martinez-Gomis, J. Improved masticatory performance in the partially edentulous rehabilitated with conventional dental prostheses. Medicina 60(11), 1790 (2024).

Leong, J. Z., Beh, Y. H. & Ho, T. K. Tooth-supported overdentures revisited. Cureus 16(1), e53184 (2024).

Jar, A. A. et al. The effect of dentures on oral health and the quality of life. Int. J. Community Med Public Health. 10(12), 5067–5071 (2023).

Hatch, J. et al. Determinants of masticatory performance in dentate adults. Arch Oral Biol 46, 641–648 (2001).

Atanda, A. J. et al. Tooth retention, health, and quality of life in older adults: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health 22(1), 185 (2022).

Sagtani, R. A., Thapa, S. & Sagtani, A. Smoking, general and oral health related quality of life–a comparative study from Nepal. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1), 257 (2020).

Al-Dwairi, Z. & Lynch, E. Xerostomia in complete denture wearers: prevalence, clinical findings and impact on oral functions. Gerodontology 31(1), 49–55 (2014).

Shankar, T. et al. Denture hygiene knowledge and practices among complete denture wearers attending a postgraduate dental institute. J Contemp Dent Pract 18(8), 714–721 (2017).

Newman, K. L. & Kamada, N. Pathogenic associations between oral and gastrointestinal diseases. Trends Mol Med 28(12), 1030–1039 (2022).

Ikebe, K. et al. Discrepancy between satisfaction with mastication, food acceptability, and masticatory performance in older adults. Int. J. Prosthodont. 20, 161–167 (2007).

Choong, E. et al. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) after rehabilitation with removable partial dentures (RPDs): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 127, 104351 (2022).

Al Quran, F. et al. Influence of psychological factors on the acceptance of complete dentures. Gerodontology 18(1), 35–40 (2001).

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Rasha A. Alamoush Methodology: Rasha A. Alamoush, Hebatullah N. Abu-Mahfouz, Rasha J. Rahhal Data Curation: Rasha A. Alamoush, Rasha J. Rahhal, Omar M. Alakhras, Renad S. Thaher Formal analysis: Mahmoud K. AL-Omiri, Julfikar Haider Validation: Mahmoud K. AL-Omiri, Julfikar Haider Writing—Original Draft: Rasha A. Alamoush, Hebatullah N. Abu-Mahfouz, Rasha J. Rahhal, Marwa M. Alnsour, Omar M. Alakhras, Renad S. Thaher, Writing—Review & Editing: Julfikar Haider, Mahmoud K. AL-Omiri.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alamoush, R.A., Abu-Mahfouz, H.N., Rahhal, R.J. et al. Impact of a removable prosthesis on chewing ability, quality of life, and patient satisfaction. Sci Rep 15, 39038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23340-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23340-0