Abstract

Rice husk is an agricultural waste from rice milling and nowadays represents an important substitute of silica in synthesis protocols of industrial minerals. Synthesis of monomineralic powders of Analcime by rice husk is here achieved with the conventional hydrothermal method; an improvement in synthesis conditions compared to the past is achieved by lowering rice-husk calcination temperatures, synthesis temperatures, crystallization times and by avoiding aging times. Rice husk is subjected to calcination at the temperature of 550 °C and then mixed with NaOH and NaAlO2. The experiment is performed at environment pressure and 170 ± 0.1 °C for 77 h. Analcime is characterized by X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy, infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Cell parameters and the amount of amorphous phase in the synthesis powders is described with quantitative phase analysis using the combined Rietveld and reference intensity ratio methods. The degree of purity of Analcime is calculated in 97,53% at 12 h. The results show that rice husk waste represents a good alternative silicon source, and it can be used to produce pure analcime crystals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silica is the most abundant free oxide (mainly as quartz) in the earth’s crust, yet despite this abundance, quartz is not extensively used in chemical engineering since amorphous silica is required for easy reaction leading to industrial mineral synthesis. Amorphous silica is mainly produced by synthetic means for its use in technological applications and it is one of the valuable inorganic multipurpose chemical compounds1. Naturally or anthropic amorphous silica can provide an alternative source to replace commercial silica precursor; the sources of silica include fly ash, high-temperature calcined kaolinite, diatomite, tripolaceous rocks, halloysite etc. These silica sources have been widely and successfully used in the synthesis of useful minerals such as zeolites and feldspathoids2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Among silica found in agro waste, rice husk (RH) has been converted into more valuable end product11,12. RH is an agricultural waste from rice milling accounting for ca. one-fifth of the annual gross rice production of the world13 i.e. the world RH production amount is approximately 40 million metric tons per year14. RH is usually composed of organic compounds such as lignin, cellulose, which vary with variety, climate and geographical position15; the most abundant constituent of RH is amorphous silica according to16. The burning of rice husk in air results in the formation of rice ask ash (RHA) with a content in SiO2 that varies from 85% to 98% depending on the burning conditions, the furnace type, the rice variety, the rice husk moisture content etc17. Rice hush ash (RHA) is frequently converted into rice hush ash (RHA) on a local or industrial scale for use as a biofuel; the resulting RHA is an industrial waste that requires management and storage. The large amount of amorphous silica obtained from this source provides an abundant and cheap alternative of silica for many industrial uses18,19,20.

Many applications of RHA concern the synthesis of zeolites21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Zeolites are crystalline, hydrated aluminosilicates constituted by TO4 tetrahedra (Al, Si) where each apical oxygen atom are shared with an adjacent tetrahedron to form regular intracrystalline cavities and channels of atomic dimensions. Analcime, with the ANA framework structure, is the smallest-pore zeolite and it exhibits a compact structure compared to other zeolites with an idealized unit cell of Na16Al16Si32O96 16H2O30.

Analcime is a zeolite which can be used for water retention and as pozzolanic material in cement mortar and concrete31,32. Also, applications in catalysis33, stomatology, i.e. ceramics for dental repair and implants34,35 are demonstrated.

Even if Analcime is not rare in nature, abundant monomineralic supplies of this mineral occur in limited sites of the world. For this reason, recent research is moving towards the synthesis of this mineral by using different sources of silica and alumina9.

Analcime is synthesized under hydrothermal conditions (100–310 °C) by alkaline aluminosilicate gels, or alternatively from cheap materials, i.e. natural glasses36, conformed ashes37, clinker38, quartz syenite powders39, clays40,41,42, silica extracted from stem of sorghum ash43.

As regards the use of Rice husk, Gookhale et al.44 used rice-husk ash, sodium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide and silica gel as starting materials for the initial mix for the synthesis of Na-X and other associated zeolites. Among them also analcime was synthesized but authors only provide the thermal study of the synthesized zeolites; Kongkachiuchay & Lohsoontorn45 synthesized Analcime and Na-P zeolites starting from perlite and rice-husk; the synthesis was carried out hydrothermally with SiO2/Al2O3 molar ratios of 1 to 40, NaOH concentrations of 1 to 4 N, and pressure of 1 atm. Temperature varied between 140° to 170 °C and the solid ratio was fixed at 15 (wt./vol.) for all experiments. The products were characterized by BET, XRD and SEM analyses. Unfortunately, the authors obtain polymineralic products consisting of Na-P, Analcime and Sodalite and in no case do they obtain isolated analcime. Also Pimraksa et al.,46 obtained Analcime as by product in the synthesis of P zeolite from RHA and fly ash.

In 2010 Azizi et al.20 operated the dissolution of RH into a KOH solution; the author indicate that the dissolution of silica is very slow at room temperature, so it was assisted by heating the sample in an oven at 70 °C for 1 week. Then synthesis of analcime is reached through a combination of conventional hydrothermal heating and microwave-assisted method. After 2 h of microwave heating the mixture is conventionally hydrothermally treated at 180 °C for 16 h. These authors stated that the use of the combined hydrothermal-microwave technique improves the kinetics in the synthesis of Analcime, however there is no comparison between the traditional hydrothermal method and the microwave-combined one either in the work or as a comparison to past literature.

In 2012 Atta et al.47, obtained Analcime by mixing metakaolin and RHA after 72 h aging and 24 h reaction time at temperature of 180 °C. More recently Setthaya et al.48 synthesized Faujasite (Linde B2) and Analcime using RHA and metakaolin; in particular, Analcime is obtained at 120 °C in 12 h in coexistence with Linde B2 zeolite. The last attempt in the synthesis of analcime from RHA is done by Ghasemi et al.,49 that obtain the phase at 150 °C after 48 and 96 h by varying the SiO2/Al2O3 from 176 to 40, respectively.

In this work we demonstrate that it is possible to synthesize monomineralic powders of Analcime from RHA with the conventional hydrothermal method by avoiding microwaves, aging times or long-time thermal assisted-dissolution of RH in an alkali medium. Moreover, a more cost-effective synthesis protocol compared to previous attempts is pursued also through by lowering: (i) synthesis temperatures (ii) crystallization times and (iii) rice-husk calcination temperatures.

It must also be said that no one has actually conducted a study aimed at quantifying the purity of the synthetic product, and/or at investigating the possible presence of unreacted and/or amorphous material9. Systematic samplings during the experimental run enable to follow the progress in the crystallization of the mineral and allow to determine the time at which the climax in the crystallization is reached. The degree of purity of the synthesized powders expressed in terms of absence of amorphous phases and impurities coming from rice husk is here defined through a quantitative phase analysis approach using the combined Rietveld and reference intensity ratio methods5.

To summarize: this study aims to demonstrate that Analcime can be produced from RHA at lower RH calcination and synthesis temperatures than those described in the literature and, above all, with much shorter synthesis times, since all these requirements are critical for an industrial transfer of the process in terms of process economics. Furthermore, for the first time the degree of purity of the synthesis products is accurately quantified by XRD, thus avoiding and making unnecessary other more complicated and expensive characterization methods (and, above all, much less common for routine use in an industrial plant) such as TEM, DTA-TGA, etc.

Materials and methods

RH preliminary treatments

RH coming from a rice field in NE Spain was triturated, washed with water and dried at 105 °C for 24 h to eliminate undesirable compounds or substances. Calcination was carried out in a furnace (Gefran Model 1200, Gefran Spa, Brescia, Italy) at 550 °C and 1 atm for 6 h50. Once the calcination temperature was reached, the crucibles were left in the furnace for 2 h and then removed and cooled at room temperature51.

RHA composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF), by means of a WDXRF, Panalytical, Axios PW 4400/40 sequential spectrophotometer. Major element determination was carried out at the Centres Cientifics i Tecnològics de la Universitat de Barcelona (CCiT-UB). For major element determination has been carried out using fused pearls (lithium tetra borate pearls at a dilution of 1/20). Pearls were obtained by triplicate (original, duplicate and clean pearl) in a Pt crucible and collector dishes, using LiI as a viscosity corrector. The Pt crucible and dish was periodically cleaned with nitric acid. The spectrometer was calibrated using a set of more than 60 international standards52,53,54 To analyze an ash with such a high silica content, an ad-hoc procedure was developed consisting of mixing 1:2 and 1:3 proportions of international standards of basaltic composition (kindly provided to DG for Geological Survey of Japan) with the RHA, obtaining results in the calibration range rhyolite-andesite of the instrument. The well-known problem related to the determination of the light element Na by XRF in low contents55 has been solved with an in-house calibration laboratory with inner standards previously also analyzed by AAS56. The NaOH and NaAlO2 used in the synthesis protocol were purchased from Riedel-de Haën (Honeywell Riedel-de Haën, Bucharest, Romania). The purity of the reagent was of 99%.

Analcime synthesis

0.94 g of the so obtained RHA were put in a 30 ml NaOH 8% solution (2 mol/l). 1.39 g NaAlO2 were added as alumina source to 30 ml NaOH 8% solution. After clearness of the solutions were reached, the silicate solution was gradually mixed with aluminate solution in the ratio of 1: 0.35. The initial mixture had the composition: 5 SiO2 – 1.00 Al2O3 – 3.2 Na2O – 666 H2O.

The mixture was homogenized for 2 h with a magnetic stirrer. Then was put inside a stainless-steel hydrothermal reactor and heated at 10 °C/min until the desired temperature (170 °C). Synthesis products were sampled periodically from the reactor, filtered with distilled water and dried in an oven at 40 °C for a day.

The entire synthesis procedure was replicated 5 times, but the results of only one experiment are reported below for indicative purposes.

Characterization of synthesis products

The RHA and products of synthesis were analysed by powder X-ray diffraction (XRPD) using a RIGAKU “MiniFlex II” characterized by a Bragg-Brentano geometry (CuKa = 1.5405 Å, 30 kV, 15 mA, 5–70° 2theta scanning interval, step size 0.02° 2theta, acquisition speed 0.033°/sec). Identification of analcime and relative peak assignment was performed with reference to the following JCPDS code: 00-019-1180. Both the crystalline and amorphous phases in the synthesis powders were estimated using quantitative phase analysis (QPA) applying the combined Rietveld and reference intensity ratio (RIR) methods9; corundum NIST 676a was added to each sample, amounting to 10% (according to the strategy proposed by Novembre et al.9 and the powder mixtures were homogenized by hand-grinding in an agate mortar. Data were acquired in the angular range 5–70° 2theta, steps of 0.02° and 10s step-1, 0.5° of divergence slit and 0.1 mm of receiving slit.

Data were processed with the GSAS software57 and the graphical interface58 starting with the structural model proposed by Gatta et al.59 for Analcime.

Morphological analyses were performed with a scanning electron microscope (Phenom XL SEM-EDX) with operating conditions of 15 kV and 2–15 μm focal-spot diameter.

The specific surface and porosity were obtained by applying the BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) method with N2 using a Micromeritics ASAP2010 instrument (operating from 10 to 127 kPa)3.

IR spectrum was taken with a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1 S FTIR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy) equipped with a sealed and desiccated interferometer, a DLATGS (Deuterated Triglycine Sulphate Doped with L-Alanine) detector and a single reflection diamond ATR crystal (QATR 10, Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy)60. FTIR spectrum was recorded in the range from 4000 to 400 cm− 1 co-adding 45 interferograms at a resolution of 4 cm− 1 with Happ–Genzel apodization60. Measurements were performed in triplicate. Data were processed with the software LabSolution IR version 2.27 (Shimadzu Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy).

Raman spectrum was acquired using an XploRA PLUS Raman spectrometer by HORIBA equipped with deep-cooled CCD detector technology at the following conditions: T = 300 K, range 200–1200 cm − 1 and 1800-line/mm grating. Data were processed with LabSpec 6.6.1.14 (Horiba, Japan) and Origin 8.5.

Results and discussion

XRPD and XRF analyses performed on RHA indicate an amorphous character and a silica content of 98.48%, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 1).

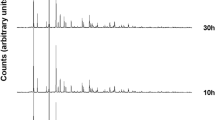

Results of XRPD analyses performed on the synthesis run conducted at 170 °C are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Appearance of Analcime (ANA) zeolite is evident at 8 h. The existence field of the zeolite is very large; in fact, the phase remains isolated for a long time and does not change in other phases; the maximum intensity of peaks is attested at 12 h.

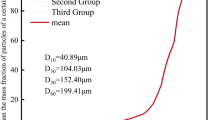

A frequently discussed issue when working with diffractograms of synthesis products is the real meaning of small peaks (which often simply correspond to instrumental noise). A very exhaustive analysis of this type of indications has been made by Steven et al.61, see Fig. 3 and references therein) by authors who have worked with RHA and who describe different products such as anorthite, clays, quartz, which can be found in the XRD of RHA and then remain inert after the reaction. We can summarize that all these products appear to correspond to soil residues from poorly washed RH; temperatures well above 700 °C are required to obtain the synthesis of these phases, a fact that has not always been considered by authors who synthesize from RHA; an ambiguity about the origin of these phases is only admissible in those authors who do not perform an XRD analysis on the raw RHA used, and who then synthesize ceramic or similar products at temperatures above 1000 °C. In our case, the RHA has been perfectly well washed in the agro-industrial process of rice recovery, as is evident in the XRD, and the minimal irregularities in the diffractogram of the synthesized products cannot be attributed with certainty to any newly formed mineral phase. The intensity of the peaks remains unchanged till 77 h; at this moment the experiment was finished. Results of the QPA analyses conducted on samples at 8, 12, 42 and 77 h are illustrated in Table 2. Analcime percentage increases over time at the expense of the amorphous component and reaches its climax at 12 h (97.53%). There is no substantial change in the percentages of the crystalline fraction versus the amorphous one passing from 12 to 77 h.

For the sample at 12 h the observed and calculated profiles and difference plots for ANA and corundum NIST 676a are reported in Fig. 3. Cell parameters of ANA, refined with cubic symmetry space group Ia-3d, remain constant within error as a function of the experimental run time. The results of the Rietveld refinements provide cell values that are in good agreement with the structural model proposed by Gatta et al.56.

Figure 4a-b reports SEM images of ANA crystals at 170 °C (10 h). It results an average maximum length of single crystals observed to be around 10 μm and of agglomerate around 40 μm. Using the BET method, Analcime was found to have a specific surface area of 1.98 m2/g and the average pore volumes of 0.0016 Å.

Further characterizations were carried out on the sample at 12 h. Figure 5 illustrates the infrared spectrum of the sample. The significant broad peak is located at 1623 cm− 1 for O-H bending, respectively. The band at 975 cm− 1 is attributed to the stretching mode of O-Na-O. The bands at 770, 732, 686 and 625 cm− 1 are attributed to Si-O-Si symmetric stretching vibration. Bands at 443 is characteristic of O-Si-O bonding mode. All these data are coherent with those available in the literature10,39,45,62,63.

Figure 6 reports the Raman spectrum for the sample at 12 h (170 °C). It results a peak at 482 cm− 1 related to the vibration mode of Al-O-Al and a peak at 388 cm− 1 associated to the vibration mode of Si-O-Si. These data are coherent with findings by Tsai et al.64 that report the characteristic peaks in the region 379–392 cm− 1 and 475–497 cm− 1 associated to the singly-connected four-cycle chain of Analcime group. The peak at 295 cm− 1 is assignable to the vibration mode of Na-O65.

The use of recycled materials, also called secondary raw materials, has already been widely investigated in the past with reference to the synthesis of zeolitic minerals and fits into the broader framework of the circular economy and processes with low environmental impact. As far as Analcime is concerned, it has already been synthesized in the past from natural materials, one of these is RH20,44,45,46,47,48,49. Table 3 summarizes the attempts by various authors to synthesize analcime from RHA with specification of starting materials, calcination temperatures of RH, experimental conditions and obtained phases. Comparing the bibliographic data with the present work shows an improvement in the synthesis conditions from both an economic and kinetic point of view. The first improvement concerns the lowering of the calcination temperature of RH, with evident economic benefits in the experimental protocol. Azizi et al.20 operate a calcination temperature of RH of 600 °C, while Kongkachiuchay & Lohsoontorn45, Pimraksa et al.46, and Setthaya et al.48 of 700 °C; Atta et al., calcinated at 800 °C. We lowered the calcination temperature to 550 °C; as a general rule we can note that after 700 °C the amorphous silica starts to crystallize (first as cristobalite, then as quartz and/or tridimite), therefore is not a good idea in terms of success of the reaction to operate with RHA calcined close to the upper limit of 700 °C.

As far as synthesis temperature is concerned, the lowest temperatures are reported by Kongkachiuchay & Lohsoontorn45 and Setthaya et al.46, respectively of 140° and 120 °C. However, it must be said that these authors do not obtain analcime as an isolated phase.

Regarding synthesis times, the lowest values are attested at 12 h and reached by the present work and by Setthaya et al.48; unfortunately, and as above stated, the latter get a combination of analcime and Linde B2 zeolite.

Looking at the data in Table 3, a fundamental fact emerges: only in the present study and in that of Azizi et al.20 Atta et al.47 and Ghasemi et al.49 is analcime obtained as an isolated phase. In the other cases, analcime is a by-product.

Given this fact, it is convenient to deepen the comparison further between the present work and those by Azizi et al.20, Atta et al.47 and Ghasemi et al.49. Firstly, and as above stated, both Azizi et al.20 and Atta et al.47 report higher calcination and synthesis temperatures with respect to our work but above all they indicate reactant pretreatment processes in the experimental procedure. Pretreatment processes in analcime synthesis can be extraordinarily complex and delicate66, which goes directly against the possibility of a simple industrial implementation of what is obtained in the laboratory. Azizi et al.20 operate a preliminary thermal treatment at 70 °C to mix RH with NaOH and get analcime after 2 h of microwave irradiation and 16 h hydrothermal at 180 °C. Also Atta et al.47 report a period of 72 h aging followed by 24 h of hydrothermal treatment. On the other hand, our protocol does not involve any preliminary thermal treatment to mix RH with NaOH and no microwave treatment is required to speed up the synthesis process. In the present work Analcime crystallizes via the hydrothermal method at only 8 h at 170 °C, reaching the maximum peak intensities at 12 h. The existence field of Analcime is very large; in fact, no phase replaces it in the time interval 8–77 h.

Let’s finally compare our results with those by Ghasemi et al.49; even if it is true that their experiment is better from the point of view of synthesis temperature (150 °C against our 170 °C), it must be specified that the synthesis times are considerably longer than the 8 h of the present work, reaching 48–96 h. So maybe it isn’t economically worth lowering the temperature if it takes such a long time. Another criticism highlighted in the work by Ghasemi et al.49 lies in the definition of the purity grade of the synthetic powders. The procedure indicated by the authors refers to obsolete methodologies (the use of the ratio of the sum of the areas of all peaks in the whole area of the XRD diffractogram multiplied by 100); in this work, instead a QPA analysis of the phases is conducted using the combined Rietveld-RIR method with an internal standard. This methodology checks for the presence of amorphous residues or even impurities in the starting material; moreover could the desired phase not be isolated, but in coexistence with others and the QPA analysis helps to solve this problem.

But the major criticism found in the work of Ghasemi et al.49 refers to the study of crystal particle size. SEM investigation gives clear evidence of single crystals of analcime with distinguable cristalline faces and edges and the mean diameter of particles is around 6 microns. Despite this the average crystal size of synthesized products is calculated by the authors by the Scherrer equation49:

τ = Kλ/βcosϑ.

where τ is the crystallite size, K is a constant (0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength, β is the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak, and θ is the Bragg angle.

They obtain a value of 25.1 nm for the calculated size of the crystal with this method, obtaining an evident inconsistency with the data obtained from the SEM analysis. Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi67 makes a precise review of the calculation of crystallite size of materials by the use of the Sherrer equation. In fact, even if the mean size of the ordered (crystalline) domains may be smaller or equal to the grain size evidenced by the SEM, the Scherrer formula can be used for crystallite sizes up to 100–200 nm as observed by SEM. Thus the methodology followed by the authors appears conceptually incorrect, i.e. the Sherrer equationn is applicable only in the presence of nanometric agglomerates highlighted by SEM analysis.

Ultimately the present work results in an experimental procedure cheaper and faster with respect to previous bibliography. A reduction of crystallization temperatures and times, the lack of preliminary pre-treatments is testified. Moreover, for the first time compared to the past, here the degree of purity of the synthetic products in a quantitative precise way is defined.

Conclusion

The interesting chemical and physical properties of ANA zeolite have led to its use in numerous industrial fields. Although analcime deposits are known in nature, they are rarely exclusively monomineralic, nor do they typically have the purity that can be achieved through controlled synthesis in an industrial process. While some uses of analcime can currently be met with natural analcime, those with the greatest added value are the fastest growing and require high-purity single-phase products. However, the production of the synthetic zeolite involves the consumption of expensive commercial reagents; for this reason, the use of alternative source of silica has been strongly enhanced over the past decades leading to the lowering of production costs.

In this work, we demonstrate the possibility of direct hydrothermal synthesis of high-purity analcime (97.53%) in just 12 h. The only pretreatment process required is the transformation by combustion of RH into RHA, at a lower temperature (550 °C) than previously reported in the literature. This process involves the utilization of a waste product, which otherwise must be managed and stockpiled, by using it as biofuel (another added gain). The synthesis we performed is perfectly stable over the range of 12 h to 77 h, when the experiment was interrupted, as its extension was of no interest. The used approach of spectroscopic, physical and morphological characterizations confirms the effectiveness of the synthesis protocol. We would like to emphasize here that the quantitative diffractometric characterization of the synthesized products represents an advance over previous work in this synthesis.

Finally, the simplicity of the process and the type of reagents used strongly suggests that the transfer to an industrial process with routine controls under economically viable conditions is feasible; this referred to the current and foreseeable market context, at least in the southern European countries where RH is abundant as waste and how-know is available.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Londeree, D. J. Silica–Titania Composites for Water Treatment. M. Eng., Thesis, University of Florida (2002).

Novembre, D., Di Sabatino, B., Gimeno, D., Garcia Valles, M. & Martinez-Manent, S. Synthesis of Na-X zeolites from tripolaceous deposits (Crotone, Italy) and volcanic zeolitized rocks (Vico Volcano, Italy). Micropor Mesopor Mat. 75, 1–11 (2004).

Novembre, D., Di Sabatino, B. & Gimeno, D. Synthesis of Na-A zeolite from 10 Å Halloysite and a new crystallization kinetic model for the transformation of Na-A into HS zeolite. Clay Clay Min. 53 (1), 28–36 (2005).

Novembre, D., Di Sabatino, B., Gimeno, D. & Pace, C. Synthesis and characterization of Na-X, Na-A and Na-P zeolites and hydroxysodalite from metakaolinite. Clay Min. 46, 336–354 (2011).

Novembre, D., Pace, C. & Gimeno, D. Syntheses and characterization of zeolites K-F and W type using a diatomite precursor. Mineral. Mag. 78, 1209–1225 (2014).

Novembre, D. & Gimeno, D. The solid-state conversion of Kaolin to KAlSiO4 minerals: the effects of time and temperature. Clays Clay Min. 65 (5), 355–366 (2017).

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D., d’Alessandro, N. & Tonucci, L. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of kalsilite by using a kaolinitic rock from Sardinia, Italy, and its application in the production of biodiesel. Mineral. Mag. 82 (4), 961–973 (2018).

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D. & Poe, B. Synthesis and characterization of leucite using a diatomite precursor. Sci. Rep. 9, 10051–10061 (2019).

Novembre, D. & Gimeno, D. Del Vecchio, A. Improvement in the synthesis conditions and studying the physicochemical properties of the zeolite Li-A(BW) obtained from a kaolinitic rock. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 5715–5723 (2020).

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D. & Del Vecchio, A. Synthesis and characterization of Na-P1 (GIS) zeolite using a kaolinitic rock. Sci. Rep. 11, 4872–4883 (2021).

Seung, G. W., Byung, Y. C., Yoon, L., Duck, J. Y. & Hyeun-Jong, B. Enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of rapeseed straw by popping pretreatment for bioethanol production. Bioresour Technol. 102, 5788–5793 (2001).

Ventak, S. M. & Babu, P. V. Studies on the adsorption of brilliant green dye from aqueous solution onto low-cost NaOH treated saw dust. Desalination 273, 321–329 (2011).

Feng, Q., Lin, Q., Gong, F., Sugita, S. & Shoya, M. Adsorption of lead and mercury by rice husk Ash. J. Coll. Interf Sci. 278 (1), 1–8 (2004).

Conradt, R., Pimkhaokham, P. & Leela-Adisorn, U. Nano-structured silica from rice husk. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 145, 75–79 (1992).

Yalçin, N. & Sevinç, V. Studies on silica obtained from rice husk. Ceram. Int. 27 (2), 219–224 (2001).

Chen, J. M. & Chang, F. W. The chlorination kinetics of rice husk. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 30, 2241–2247 (1991).

Azizi, S. N. & Yousefpour, M. Spectroscopic studies of different kind of rice husk samples grown in North of Iran and the extracted silica by using XRD, XRF, IR, AA and NMR techniques. Eurasian J. Anal. Chem. 3, 298–306 (2008).

Della, V. P. & Kühn, I. Hotza. Rice husk Ash as an alternate source for active silica production. Mater. Lett. 57 (4), 818–821 (2002).

Bhagiyalakshmi, M., Ramani, L. J. Y. & Jang, H. T. Utilization of rice husk Ash as silica source for the synthesis of mesoporous silicas and their application to CO2 adsorption through TREN/TEPA grafting. J. Hazard. Mat. 175 (1), 928–938 (2010).

Azizi, S. N. & Maryam, Y. Synthesis of zeolites NaA and analcime using rice husk Ash as silica source without using organic template. J. Mat. Sci. 45 (20), 5692–5697 (2010).

Kongkachuichay, P., Lohsoontorn, P. & and Phase diagram of zeolite synthesized from perlite and rice husk Ash. ScienceAsia 32, 13–16 (2005).

Wittayakun, J., Khemthong, P. & Prayoonkarach, S. Synthesis and characterization of zeolite NaY from rice husk silica. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 25 (4), 861–864 (2008).

Petkowicz, D. I., Rigo, R. T., Radtke, C., Pergher, S. B. & dos Santos J.H.Z. Zeolite NaA from Brazilian Chrysotile and ricehusk. Micropor Mesopor Mat. 116, 548–554 (2008).

Rahman, M. M., Hasnidab, N. & Wan Nik, W. B. Preparation of zeolite Y using local Raw material rice husk as a silica source. J. Sci. Res. 1 (2), 285–291 (2009).

Yusof, A. M., Malek, N. A. N. N. & Rashid, N. A. A. Hydrothermal conversion of rice husk Ash to faujasite-types and NaA-type of zeolites. J. Porous Mater. 17 (1), 39–47 (2010).

Tan, W. C., Yap, S. Y., Matsumoto, A., Othman, R. & Yeoh, F. Y. Synthesis and characterization of zeolites NaA and NaY from rice husk Ash. Adsorption 17, 863–868 (2011).

Ghasemi, Z. & Younesi, H. Preparation of Free-Template Nanometer-Sized Na–A and –X zeolites from rice husk Ash. Waste Biomass Valor. 3, 61–74 (2012).

Mohamed, R. M., Mkhalid, I. A. & Barakat, M. A. Rice husk Ash as a renewable source for the production of zeolite NaY and its characterization. Arab. J. Chem. 8, 48–53 (2015).

Klunk, M. A. et al. Comparative study using different external sources of aluminum on the zeolites synthesis from rice husk Ash. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 015023 (2020).

Meier, W. M. & Olson, D. H. Atlas of Zeolite Structure Types, 4th edn, 405 (Elsevier Science, 1996).

Auerbach, S. M., Carrado, K. A. & Dutta, P. K. Handbook of Zeolite Science and Technology (Marcel Dekker, 2003).

Jana, D. A new look to an old pozzolan: clinoptilolite-a promising pozzolan in concrete. In Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Cement Microscopy, Quebec, Canada (2007).

Liu, B. S., Tang, D. C. & Au, C. T. Fabrication of analcime zeolite fibers by hydrothermal synthesis. Microp Mesop. Mat. 86, 106–111 (2005).

Balandis, A. & Traidaraite, A. The influence of al containing component on synthesis of analcime of various crystallographic systems. Mater. Sci. Pol. 25, 637–647 (2007).

Rasmussen, S. T., Groh, C. L. & O’Brien, W. J. Stress induced phase transformation of a cesium stabilized leucite porcelain and associated properties. Dent. Mater. 14, 202–211 (1998).

Derkowski, A. Experimental transformation of volcanic glass from Streda nad Bodrogom (SE Slovakia). Geol. Carpath. 2002, 53. In Proceedings of the XVII Congress of Carpathian-Balkan Geological Association Bratislava (2002).

Dyer, A., Tangkawanit, S. & Rangsriwatananon, K. Exchange diffusion of Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2 + and Zn2 + into analcime synthesized from perlite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 75 (3), 273–279 (2004).

Tatlier, M., Baris Cigizoglu, K. & Tokay, B. Erdem-Senatalar, A. Microwave vs. conventional synthesis of analcime from clear solutions. J. Cryst. Growth. 306, 146–151 (2007).

Ma, X., Yang, J., Ma., H., Liu, C. & Zhang, P. Synthesis and characterization of analcime using quartz syenite powder by alkali-hydrothermal treatment. Microp Mesop. Mat. 201, 134–140 (2015).

Hegazy, E. Z., El Maksod, A., Abo, E., Enin, R. M. M. & I. H. & Preparation and characterization of Ti and V modified analcime from local Kaolin. Appl. Clay Sci. 49, 149–155 (2010).

Novembre, D. & Gimeno, D. Synthesis and characterization of analcime (ANA) zeolite using a kaolinitic rock. Sci. Rep. 11, 13373–13382 (2021).

Kadhim, R. S., Disher, I. A. & Jabbar, S. M. Synthesis of geopolimer.based phase pure analcime and cancrinite zeolite via simple hydrtothermal method. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 10 (17S), 161–172 (2025).

Azizi, S. N., Ghasemi, S. & Derakhshani-mansoorkuhi, M. The synthesis of analcime zeolite nanoparticles using silica extracted from stem of sorghum halepenesic Ash and their application as support for electrooxidation of formaldehyde. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 21181–21192 (2016).

Gookhale, K. V. G. K., Dalai, A. K. & Rao, M. S. Thermal characteristics of synthetic sodium zeolites prepared with silica from rice-husk Ash. J. Therm. Anal. 31, 33–39 (1986).

Kongkachuichay, P. & Lohsoontorn, P. Phase diagram of zeolite synthesized from perlite and rice husk Ash. ScienceAsia 32, 13–16 (2006).

Pimraksa, K., Chindaprasirt, P. & Setthaya, N. Synthesis of zeolite phases from combustion by-products. Waste Manag Res. 28 (12), 1122–1132 (2010).

Atta, A. Y., Jibril, B. Y., Aderemi, B. O. & Adefila, S. S. Preparation of analcime from local Kaolin and rice husk Ash. App Clay Sci. 61, 8–13 (2012).

Setthaya, N., Pindi, C., Chindaprasirt, P. & Pimraksa, K. Synthesis of Faujasite and analcime using of rice husk Ash and Metakaolin. Adv. Mater. Res. 770, 209–212 (2013).

Ghasemi, Z., Sari, L. V., Younesi, H. & Kazemian, H. Synthesis of nanosized ZSM-5 zeolite using extracted silica from rice husk without adding any alumina source. Appl. Nanosci. 5, 737–745 (2015).

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D., Pasculli, A. & Di Sabatino, B. Synthesis and characterization of sodalite using natural kaolinite: an analytical and mathematical approach to simulate the loss in weight of Chlorine during the synthesis process. Fresen Environ. Bull. 19 (6), 1109–1117 (2010).

Pasculli, A. & Novembre, D. A phenomenological–mathematical approach in simulating the loss in weight of Chlorine during sodalite synthesis. Comput. Geosci. 42, 110–117 (2012).

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D., Cappelletti, P. & Graziano, S. F. A case study of zeolitization process: Tufo Rosso a scorie Nere (Vico volcano, Italy): inferences for a general model. Eur. J. Mineral. 33, 315–328. https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-33-315-2021 (2021).

Aulinas, M. et al. The plinian Mercato eruption of Somma vesuvius: magma chamber processes and eruption dynamics. Bull. Volcanol. 70, 825–840 (2008).

Gisbert, G. & Gimeno, D. Ignimbrite correlation using whole-rock geochemistry: an example from the sulcis (SW Sardinia, Italy). Geol. Mag. 154 (4), 740–756 (2017).

Gimeno, D. & Puges, M. Caracterización química de La vidriera histórica de Sant Pere i Sant Jaume (Monestir de Pedralbes, Barcelona). Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 41 (2), 13–20 (2002).

Aulinas, M. et al. The Plio-Quaternary magmatic feeding system beneath Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain): constraints from thermobarometric studies. J. Geol. Soc. 167 (4), 785–801 (2010).

Larson, A. C. & Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS General Structure Analysis System. Document Laur 86–748 (Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1997).

Toby, B. H. EXPGUI, a graphical user interface for GSAS. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 34, 210–213 (2001).

Gatta, G. D., Nestola, F. & Ballaran, T. B. Elastic behaviour, phase transition, and pressure induced structural evolution of analcime. Am. Mineral. 91, 568–578 (2006).

Ciulla, M. et al. Enhanced CO2 capture by sorption on electrospun Poly (Methyl Methacrylate). Separations 10, 505–521 (2023).

Soen, S., Elvi, R. & Yazid, B. Routes for energy and bio-silica production from rice husk: A comprehensive review and emerging prospect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 149, 111329 (2021).

Yuan, J., Yang, J., Ma, H., Liu, C. & Zhao, C. Hydrothermal synthesis of analcime and hydroxycancrinite from k-feldspar in Na2SiO3 solution: characterization and reaction mechanism. RCS Adv. 6 (59), 54503–54509 (2016).

Atta, A. Y., Jibril, B. Y., Aderemi, B. O. & Adefila, S. S. Preparation of analcime from local Kaolin and rice husk Ash. Appl. Clay Sci. 61, 8–13 (2012).

Tsai, Y. L. et al. Raman spectroscopic characteristics of zeolite group minerals. Minerals 11, 167–181 (2021).

Guiar, A. C. et al. Raman investigation of SUZ-4 zeolite. Micropor Mesopor Mat. 78, 131–137 (2005).

Ait Baha, A. et al. Effect of pre-treatments on analcime synthesis from abundant clay-rich illite. Clays Clay Miner. 73 (e15), 1–14 (2025).

Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi, S. A. Precise calculation of crystallite size of nanomaterials: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 968, 171914 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly acknowledge the technical staff at Universitat of Barcelona(CCiT-UB) and Chieti for their help during the development of the work. M.Menéndez (Biology fac.,UB) helped us with the calcination of RH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N. and D.G.; Data curation, D.N., D.G., L.M., A.C.T., G.R., M.C. and P.d.P.; Investigation, D.N., D.G., L.M., A.C.T., G.R., M.C. and P.d.P.; Methodology, D.N.and D.G.; Supervision, D.N. and D.G.;Writing—original draft, D.N.;Writing—review and editing, D.G., L.M., A.C.T., G.R., M.C. and P.d.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version ofthe manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novembre, D., Gimeno, D., Marinangeli, L. et al. Rice husk as raw material in the synthesis of analcime. Sci Rep 15, 38438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23349-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23349-5