Abstract

Patients with hypertension commonly experience metabolic dysfunction and cognitive decline. Previous studies have shown that sedentary behavior can affect metabolism. The weight-adjusted waist circumference index (WWI) has become a new indicator of obesity. This study examines the association between sedentary time and hypertension combined with cognitive decline (HCD), with a focus on assessing the mediating role of WWI. A total of 6098 hypertensive patients from May 2022 to July 2024 were included in this study from the hypertension follow-up system. Various statistical techniques such as logistic regression, subgroup analysis, smoothed curve fitting, and causal mediation analysis were used in the study to analyze the information collected from hypertensive patients. In completely adjusted models, there was a noteworthy statistically positive relationship between sedentary time and HCD with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.50 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (2.37, 5.16). The causal mediation analysis showed that the relationship between sedentary time and HCD was partially influenced by the mediating effect of WWI with a mediation ratio of 3.6%. Based on this study, sedentary time was significantly and positively associated with the prevalence of HCD, with WWI playing a mediating role. This finding provides a new perspective on the prevention and management of HCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a common condition characterized by elevated blood pressure levels that can lead to a variety of complications, including cognitive decline, cognitive impairment, and dementia1,2,3,4. Nowadays, hypertension combined with cognitive decline (HCD) is a growing concern. Studies have shown that up to 30% of hypertensive patients may experience some form of cognitive decline5,6. Patients with hypertension have an approximately 40% increased risk of developing cognitive dysfunction compared to normal subjects4. In the Chinese population, hypertension is associated with a 1.86-fold increased risk of dementia and a 1.62-fold increased risk of mild cognitive impairment7.

In recent years, sedentary behavior has also become more prevalent in modern society due to technological advances and the increase in sedentary occupations8,9, and the relationship between sedentary behavior and obesity and cardiovascular disease has received much attention. Studies have shown that prolonged sedentary behavior increases the risk of obesity and negatively affects cardiovascular health and cognitive function10,11. Studies have shown that sedentary behavior leads to lower metabolic levels in the body12, and has harmful effects on blood glucose control and brain function, which in turn affects the performance of cognitive functions13.

In terms of the relationship between sedentary behavior and obesity, researchers have been working hard to explore this area. The Weight-adjusted Waist Index (WWI), an index originally proposed by Park et al., pointed out that traditional body mass indexes (e.g., BMI) do not reflect the distribution of fat around the waist well14. As a new type of body mass index, WWI is derived by combining waist circumference with body weight, which helps to assess an individual’s fat and muscle mass more accurately and can more accurately determine the degree of obesity and its association with cardiovascular disease risk in an individual14,15. WWI considers waist circumference and the square root of body weight to measure body composition in detail. This method helps to reduce the obesity paradox14,16. By distinguishing fat and muscle mass, WWI can more accurately assess the health risks associated with obesity, especially in cardiovascular diseases. Previous studies have confirmed a significant association between high WWI and a variety of diseases, including hypertension and heart failure17,18,19. In addition, studies have shown that WWI is superior to BMI, waist circumference(WC), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHtR) in predicting cardiovascular mortality20,21,22. One of the concerns of this study is whether WWI mediated the association between sedentary time and HCD. The selection of potential mediators was based on evidence that (1) a prospective cohort study demonstrated that sedentary time contributes to central obesity23; and (2) previous evidence that WWI is an independent risk factor for cognitive decline24.

The novelty of this study is its unique survey of hypertension database data to validate the relationship between HCD and sedentary behavior, and the potential mediating role of WWI in this relationship, in a large sample population. To provide valuable insights into the relationship between HCD, sedentary behavior, and WWI, and suggest more reasonable lifestyle intervention suggestions.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

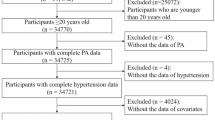

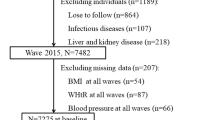

Data for this observational study were obtained from the Hypertension Follow-up System. The study was a large-scale survey conducted by the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, in which nine hospitals in Jinan, Weifang, Yantai, Zibo, Tai ‘an, Dongying, Dezhou and Jining participated, to collect information on the general condition, physical activity level, sleep quality, and cognitive function of hypertensive patients. The total sample size of the analysis was 6098 cases. Among them, the Jinan region contributed 434 samples, Weifang region contributed 1808 samples, Yantai region contributed 2720 samples, Zibo region contributed 353 samples, Tai ‘an region contributed 397 samples, Dongying, Dezhou, and Jining regions contributed 386 samples. We rigorously screen and evaluate these samples to ensure that each step of the sample selection and data collection process follows uniform standards and protocols to ensure the reliability and repeatability of the research results. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine ((2023) Review No. (109) -KY), all study subjects signed an informed consent form. The study population included patients with primary hypertension aged 40 years and above. Also, patients with secondary hypertension, comorbid psychiatric disorders, alcoholism, and psychotropic substance abuse were excluded from the study. The process of screening subjects is shown in (Fig. 1).

Assessment of weight‑adjusted‑waist index

The weight‑adjusted‑waist index (WWI) is a measure of obesity using WC and weight, with higher WWI scores indicating greater obesity. Body weight and waist circumference are measured by a trained healthcare professional, and their proficiency is regularly verified. To ensure accuracy, it is recommended that the subjects wear the minimum amount of clothing when weighed. Waist circumference was measured using a tape at specific anatomical landmarks and recorded in centimeters (cm). Weight measurement also followed a standard procedure and was recorded in kilograms (kg). In this study, WWI = WC / (weight0.5)14,25.

Assessment of sedentary time

The Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire long-form (IPAQ) was used to measure the physical activity level of patients with hypertension26,27.The average sedentary time per day was calculated by multiplying the weekday estimate by five and the weekend estimate by two and dividing by seven28.

Diagnostic criteria

The patients were evaluated by two experienced cardiologists according to the following criteria. The diagnostic criteria for hypertension were the diagnostic criteria mentioned in the ' Chinese Hypertension Prevention and Treatment Guidelines (2018 Revision) '29issued by the Chinese Hypertension Prevention and Treatment Guidelines Revision Committee : SBP ≥ 140mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90mmHg in a quiet state, or antihypertensive drugs (including: ACE inhibitors (ACEI), Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), β-receptor blocker, Calcium channel blockers (CCB), and Diuretics) are currently being used. When measuring blood pressure, repeated measurements should be taken at intervals of 1 ~ 2 minutes, and the average value of the two readings should be recorded. The Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was utilized to assess cognitive function. The cognitive domains evaluated by the MMSE include orientation, memory, attention, naming, repetition, comprehension, writing, and construction30. According to previous studies31,32,33, MMSE scores higher than 18 and lower than 27 were defined as cognitive decline. We assessed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) for sleep quality. The PSQI score above 7 indicates sleep disorders34,35.

Assessment of covariates of interest

To fully examine the possible link between sedentary time and HCD, this study considered a wide range of covariates, such as demographic information, medication history, body measurements, laboratory tests, and questionnaire survey results. The physical examination module includes the measurement of systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), height, weight, WC and other related parameters in patients with hypertension. Biochemical indicators including fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and serum creatinine (SCr) were detected by qualified medical professionals. In addition, experienced echocardiography experts measured the right atrial diameter (RAD), left atrial diameter (LAD), right ventricular diameter (RVD), and left ventricular diameter (LVD), and the level of physical activity was obtained by trained personnel through the IPAQ. In this study, we classified occupation types into three categories: mental labor (professionals, government), both manual and brain labor (skilled workers, service providers, merchants), and manual labor (farmer, factory worker, manufacturing, transportation)36,37.

Statistical analysis

The normality test of continuous variables was performed according to the data characteristics. Normally distributed data is presented as mean ± SD; non-normally distributed data as median (interquartile range). Group comparisons were conducted as follows: Two-group comparisons: Independent t-test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution); multi-group comparisons: One-way ANOVA for homogeneity (normal distribution) or Kruskal-Wallis test (non-normal distribution). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (%) and compared using the Pearson χ² test (expected frequencies ≥ 5). Post-hoc t-tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction to account for multiple pairwise comparisons. Additionally, post hoc analysis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA for k samples, following the Kruskal-Wallis test. Chi-square analysis was also performed with post-hoc Bonferroni adjustment to manage multiple comparisons. Due to the skewed distribution of sedentary time, natural logarithms are used for data conversion before analysis and are analyzed as continuous variables in multivariate models and mediation effect analysis (per 1-SD increment). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the differences in sedentary time by quartile grouping, with quartile 1(Q1) as the reference group. We developed four logical models for the analysis: Model 1 is a univariate analysis without adjustment for any confounding variables. Model 2 was adjusted for the demographic characteristic variables (age, sex, education level, marital status, type of occupation, smoking, drinking). Model 3 added BMI, FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and SCr based on Model 2. Considering the confounding effects of sleep disorders on HCD, model 4 further included sleep disorders6,38. In addition, we conducted a subgroup analysis to test for heterogeneity and interaction in specific populations. To clearly show the linear or nonlinear relationship between HCD and sedentary time, we used the restricted cubic spline (RCS) to fit the curve. The model with the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) value was selected for RCS calculation. Finally, we use the ' mediation ' package in R for causal mediation analysis. In this study, the number of bootstrap simulations was set to 1000 times to ensure stable and reliable estimates of indirect, direct, and total effects. Studies have shown that when the number of Bootstrap iterations reaches 1000, the estimation results of the confidence interval have stabilized and can meet the accuracy requirements of most social science and medical research. Although more iterations (such as 5000 or 10000) can further improve the accuracy, it will also significantly increase the computational time and resource consumption. Considering the large sample size of this study (n = 6098), 1000 iterations ensure the stability of the results while considering the computational efficiency. HCD was treated as a binary outcome, and the mediation model was adjusted for potential confounding variables. Multicollinearity among predictor variables was assessed using the Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF). Since the outcome variable was binary, a linear approximation of the logistic regression model was used to calculate GVIF values. The results showed that most predictors had GVIF values below 5, indicating no severe multicollinearity. Although cholesterol (GVIF = 5.68) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (GVIF = 4.84) showed moderate multicollinearity, neither exceeded the threshold of 10, so they were retained in the model. Data processing and analysis were performed using R version 4.3.3 (2024-02-29), along with Zstats 1.0 (www.zstats.net) and SPSS version 26.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical baseline features of the subjects

Table 1 summarizes the clinical baseline characteristics of hypertensive patients according to their cognitive functioning status. Analyses showed statistically significant differences in the distribution of gender, education level, and type of occupation, with a higher proportion of females, primary and lower education levels, and manual laborers in HCD group (P < 0.001). In addition, the mean age was slightly higher in the HCD group (72.77 versus 64.91 years, P < 0.001). Regarding biochemical indicators, TG, TC, and LDL-C levels were significantly higher in the HNCF group than in the HCD group (P < 0.001), and Scr levels were significantly higher in the HCD group than in the HNCF group (P = 0.009). In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed in FBG (P = 0.136) or HDL-C (P = 0.131) levels between the groups.

Table 2 shows the quartiles of hypertensive patients classified according to sedentary time. As can be seen from the table, the incidence of HCD was significantly higher in group Q4 (27.97%) than in group Q1 (15.35%). Detailed post hoc comparisons are provided in Schedules 1–3.

Logistic regression analysis

Hypertensive patients were classified into two groups based on MMSE scores: Hypertensive patients with normal cognitive function: MMSE score ≥ 27; Hypertensive cognitive decline: MMSE score ≥ 18 and < 27. The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3, which shows the association between sedentary time and HCD. According to the initial model, sedentary time was significantly and positively associated with HCD (OR = 5.71; 95%CI: 3.98 ~ 8.17; P < 0.001). Model 2 (OR = 3.38; 95%CI: 2.32 ~ 4.93; P < 0.001) showed a slight decrease in dominance ratio compared to Model 1 after controlling for age, sex, education level, marital status, type of occupation, smoking, and drinking covariates. Notably, the odds ratios for Model 3 (OR = 3.40; 95%CI: 2.32 ~ 4.99; P < 0.001) were very similar to model 2 after adding covariates such as BMI and biochemical variables (FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, SCr). And interestingly, the odds ratios for Model 4 (OR = 3.50; 95%CI: 2.37 ~ 5.16; P < 0.001) were also like those of Models 2 and 3 after controlling for all variables. This suggests that for each unit increases in sedentary time (converted to natural logarithms), the prevalence of HCD increases by 250%. The positive association between sedentary time and hypertension with cognitive decline persisted when sedentary time was further divided into quartiles. In model 4, patients in the longest sedentary time group (Q4) had a 73% increase in the prevalence of HCD compared with the shortest sedentary time group (Q1).

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis of model 4 was conducted to investigate the potential differences in the relationship between sedentary time and HCD patients in different populations. The results are shown in (Fig. 2). The association between sedentary time and HCD significantly differed in various subgroups. Sedentary time had a significant effect on the risk of HCD in manual workers, both manual and mental workers, women, smokers, people with sleep disorders, and people over 65 years old (all P < 0.05). The interaction P value suggested that occupational type (P < 0.05) significantly regulated the effect of sedentary time on HCD, while other groups (P > 0.05) did not reach statistical significance.

Constrained cubic spline curve fitting

Figure 3 uses Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) to describe the relationship between sedentary time and HCD. Considering the large sample size of this study, to balance the model complexity and goodness of fit, we use the BIC criterion to determine the optimal number and location of RCS nodes39,40,41. Using this approach, a restricted cubic spline (RCS) model with three knots was identified as the most parsimonious representation of the data. Knots were placed at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the exposure distribution (corresponding to values of 1.5, 3.0, and 6.0), enabling a flexible yet interpretable characterization of the nonlinear association.

Subfigures A to D depict the relationship between sedentary time and HCD after adjusting for different covariates, respectively. The results showed that the relationship between sedentary time and HCD consistently showed a significant nonlinear trend, with or without adjustment for covariates(P<0.001). An increase in sedentary time significantly increased the risk of developing HCD, especially in moderately sedentary hypertensive patients, but the risk was moderated in extreme sedentary conditions. This further suggests that controlling moderate sedentary time is important in preventing HCD.

Association between sedentary time and HCD with the RCS function. Subfigure (A) Crude; Subfigure (B) Adjust: age, sex, education level, marital status, type of occupation, smoking, drinking; Subfigure (C) Adjust: age, sex, education level, marital status, type of occupation, smoking, drinking, BMI, FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, SCr; Subfigure (D) Adjust: age, sex, education level, marital status, type of occupation, smoking, drinking, BMI, FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, SCr, sleep disorders.

The intermediary role of WWI

We performed causal mediation analyses to explore the potential mediating role of WWI between sedentary time and the development of HCD. Table 4 presents the results of the mediation analyses, including direct effects, indirect effects, total effects, and mediation ratios. The results showed that WWI played a mediating role in the association between sedentary time and HCD. The total effect was 0.0129 (95% CI: 0.0086, 0.0166, P < 0.001), indicating a 1.29% increase in the risk of HCD for each unit increase in sedentary time. The indirect effect was 0.0005 (95% CI: 0.0001, 0.0009, P < 0.05), indicating a 0.05% effect of sedentary time on HCD through WWI. However, the direct impact was 0.0125 (95% CI: 0.0081, 0.0161, P < 0.001), meaning that sedentary time still influenced HCD after controlling WWI. This suggests that WWI has both direct and indirect effects on sedentary time and the development of HCD, of which approximately 3.6% is mediated by WWI.

Discussion

The present study provides new insights and findings regarding the mediating role of WWI in the association between sedentary time and HCD. By sampling 6098 hypertensive patients, our study found a non-linear relationship between sedentary time and HCD, characterized by a threshold effect. It is worth noting that this phase nonlinear correlation remains stable after gradually adjusting for confounding covariates from Model 1 to Model 4. Subgroup analyses showed that the effect of sedentary time on cognitive function was more pronounced in people over 65 years of age, smokers, and hypertensive patients engaged in manual labor, both manual and brain labor. Overall, sedentary behavior can increase the incidence of HCD to some extent, and this association is mediated to some extent by WWI.

In recent years, more and more scholars have begun to pay attention to lifestyle factors related to cognitive function, and have gradually reported the potential association between cognitive decline and a variety of factors such as physical activity42 and obesity43. Previous studies have reported that physical activity slows normal cognitive decline44. Merchant et al.43. found that central obesity alone or combined with high BMI was associated with lower MMSE scores, which was more pronounced in men. Notably, beyond general obesity metrics, specific behavioral patterns like sedentary time also exhibit complex health impacts. For example, Sugiyama’s study demonstrated that prolonged sitting at work was significantly associated with increased waist circumference only among desk-based workers (especially inactive males), but not in non-desk-based occupations, suggesting that the context and pattern of sedentary behavior critically modify its metabolic consequences45. The above findings highlight the rationale for incorporating multiple metrics when assessing cognitive decline risk and provide a basis for elucidating the complex etiology of cognitive decline. However, the current academic literature lacks insight into the potential association between sedentary time and HCD.

This study is the first to use a hypertension database to examine the relationship between HCD and sedentary time and to explore the potential moderating role of WWI. In previous epidemiological studies, WWI has been intensively investigated in various systemic diseases. Li46 demonstrated a significant correlation between WWI and hyperuricemia, and this correlation remained statistically significant in subgroup analyses stratified by sex, age, and ethnicity. In addition, the study found a significant positive correlation between WWI and serum uric acid in women, but not in men. In another large observational study, Li et al.47 observed a positive correlation between WWI and chronic kidney disease (CKD), consistent across subgroup analyses. The discriminatory power of WWI was superior to other obesity indicators in predicting CKD. Xiong et al.18 conducted a cross-sectional study of 5232 Chinese hypertensive patients and found a significant correlation between WWI and atherosclerosis. For every 1-unit increase in WWI, in a fully adjusted model, Brachia-ankle pulse wave velocity changed to 57.98 mm/s. This result suggests that WWI may be an important intervening factor in the management of hypertensive patients. In addition to blood pressure management, attention should be paid to the effects of body weight and WC on hypertensive patients. More than its association with atherosclerosis, WWI, a new indicator of obesity, has been linked to a variety of systemic diseases48,49.

In previous studies, sedentary behavior has been found to lead to obesity50,51,52,53, as well as elevated WC levels54,55. WC is a predictor of cardiovascular disease and is considered a more accurate indicator of visceral fat accumulation and poor metabolic status than BMI56. In a multicohort study of Hispanic and non-Hispanic overweight/obese postmenopausal women, Chang et al.57. observed a detrimental association between sedentary behaviors and higher levels of cardiometabolic risk biomarkers. The results of the study showed that for each additional hour of sedentary time, WC increased by 1.93%, BMI by 1.64%. WWI is calculated by dividing WC by the square root of body weight and is used as a quantitative indicator to assess body fat distribution in individuals. WWI provides valuable information about the ratio of body weight to abdominal fat and can better reflect the impact of obesity on metabolic risk. However, the mechanisms by which sedentary time affect WWI levels and the mediating role of WWI in increasing the risk of HCD are still incompletely understood and could be explained by a variety of potential mechanisms. Firstly, being sedentary significantly reduces energy expenditure58, which tends to lead to the accumulation of fat, especially abdominal fat59,60, increasing the risk of obesity, and leading to a rise in WWI. Secondly, a sedentary lifestyle is also associated with a low-grade inflammatory response61,62,63, characterized by elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as hs-CRP and IL-664, and the upregulation of inflammation leads to an increase in lipid storage65, which promotes obesity and visceral fat accumulation, leading to metabolic disturbances66 such as increased levels of triglycerides and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein60, further affecting abdominal fat accumulation. In addition, sedentary behavior is closely related to visceral fat accumulation67,68 with longer sedentary time being associated with less efficient fat metabolism and increased visceral fat accumulation69, which directly affects WC expansion and raises the WWI. At the same time, sedentary behavior decreases the contractile activity of skeletal muscle, which reduces the activity of lipoprotein lipase in muscle and leads to oxidative disorders70, contributing to abdominal fat accumulation. Finally, sedentary behavior significantly increases insulin resistance, which can further exacerbate abnormalities in fat metabolism70, leading to a rise in WWI and an increased risk of cognitive decline.

However, although the above biological pathways are theoretically valid, this study found that WWI can only explain a very small part (3.6%) of the association between sedentary behavior and cognitive decline. This seemingly contradictory phenomenon suggests that in addition to obesity itself, there are other key factors that play a leading role. Possible reasons for the small mediating role of WWI in cognitive function research include unmeasured confounding factors and inflammation, which may mask the potential impact of WWI on cognitive function71.First, inflammation may be a significant factor influencing the relationship between WWI and cognitive function. Studies have shown that WWI is positively correlated with systemic inflammatory indicators, such as the systemic immune inflammation index (SII) and the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI)72. This inflammatory state may affect cognitive function through a variety of ways73,74,75, such as by affecting the balance of neurotransmitters or accelerating neurodegenerative diseases76,77. In addition, inflammation may further affect cognitive function by affecting vascular health and cerebral blood flow78,79,80. Second, unmeasured confounding factors may also play an important role in the relationship between WWI and cognitive function. Studies have shown that lifestyle factors such as eating habits and socioeconomic status may affect the relationship between WWI and cognitive function81,82. In addition, genetic factors may also regulate the relationship between WWI and cognitive function by affecting the common pathway of obesity and cognitive function83. Finally, this study is a cross-sectional study and cannot determine the causal relationship. Additionally, the sample size and the representativeness of the research object may also affect the universality of the results. Future prospective studies and larger cohort studies may help to reveal the relationship between WWI and cognitive function more comprehensively.

In this study, we also found that even in hypertensive patients who do not smoke, drink, or sleep disorders, the probability of cognitive decline will increase. First of all, about the relationship between smoking and cognitive function, studies have shown that smoking may have a compensatory or protective effect on the intrinsic brain activity of patients with mild cognitive impairment84. Another study pointed out that smoking is associated with changes in brain functional connectivity in patients with mild cognitive impairment, suggesting that smoking may have a complex effect on cognitive function in some cases85. In addition, there is a correlation between smoking cessation time and dementia risk, and early smoking cessation can reduce dementia risk86. On the relationship between drinking and cognitive function, studies have shown that moderate drinking may have a protective effect on the cognitive function of the elderly. However, this protective effect is weakened in individuals with a history of drinking problems87. One study pointed out that individuals who smoked and drank heavily had a 36% faster decline in cognitive function within ten years than those who did not smoke and drank moderately88. In addition, another study found that moderate to heavy drinking was associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment in young elderly people aged 60 to 69, but heavy drinking was associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment in middle-aged and elderly people aged 70 and over89. These studies have shown that the effect of drinking on cognitive function may vary depending on individual age and drinking history. Regarding the relationship between sleep disorders and cognitive function, studies have shown that sleep disorders, such as insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea, are associated with decreased cognitive function and increased risk of dementia90. A study has shown that sleep fragmentation is associated with the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline91. However, too long or too short sleep time is also related to cognitive decline. Studies have found that individuals with excessively long or short sleep times experience a faster decline in cognitive function92. Although sleep disorders are generally considered to be an important factor in cognitive decline, hypertensive patients still face the risk of cognitive decline even in the absence of obvious sleep disorders. Hypertension, along with other modifiable risk factors such as depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and obesity, together affect the decline in cognitive function93, according to a scientific statement on heart and brain health. In addition, another study pointed out that cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity significantly increased the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in the elderly94. The above results show that the relationship between smoking, drinking, sleep disorders, and cognitive decline is complex, involving the interaction of multiple factors. Although these factors may be related to cognitive decline alone, the combined effects need further research to clarify.

In addition, the type of work is also an important factor affecting HCD. The risk of cognitive decline in intellectually intensive work (such as mental work) is significantly lower than that of people engaged in manual labor. On the contrary, manual labor or high-stress work (such as passive work or occupational stress) may increase the risk of cognitive decline. Specifically, intelligence-intensive work can provide continuous cognitive stimulation, which helps to maintain brain activity and neural plasticity, thereby delaying cognitive decline. Moreover, job complexity has also been shown to be closely related to cognitive function, and high complexity work can reduce the risk of dementia95. Therefore, based on the relationship between job type and cognitive function, we suggest that the following interventions may help to delay the decline of cognitive function: (1) Career transition and training: Encourage people engaged in physical or low-complexity work to shift to more cognitively challenging occupations, or increase the complexity of work through vocational training95. (2) Cognitive training: For people who cannot change the type of work, cognitive training (such as computerized cognitive training) can be used to simulate the cognitive stimulation effect of intelligence-intensive work96. (3) Occupational health management: Reduce occupational exposure (such as electromagnetic fields) and optimize the working environment, reducing the negative impact of occupational stress on cognitive function95. (4) Lifelong learning: Encourage middle-aged and elderly people to make up for the lack of cognitive stimulation caused by work types by continuing education or participating in cognitive activities (such as reading, learning new skills, etc.)97,98. We hope that the above measures can effectively delay the decline of cognitive function in patients and improve the quality of life of patients. Future research should further explore the impact of occupational exposure and personalized intervention strategies to provide more comprehensive support for cognitive health.

Restricted Cubic Spline demonstrates a reduced risk of HCD during prolonged sedentary periods, which may be attributed to a combination of multiple underlying mechanisms. First, the relationship between sedentary behavior and cognitive decline is complex across studies. For example, one study found a significant association between sedentary behavior and cognitive decline, particularly in older populations99. However, another study has shown that moderate cognitive activities, such as reading and writing, performed in a sitting position, are strongly associated with protective effects on cognitive function100. This suggests to us that the effects of sedentary behavior may vary depending on the specific activity type of the individual. Secondly, compensation mechanisms may play an important role in the relationship between sedentary behavior and cognitive function. Hypertension itself is an important risk factor for cognitive decline, especially in sedentary populations101,102. However, hypertensive patients belonging to the extreme sedentary group may improve brain blood circulation and neural function to a certain extent by participating in cognitively stimulating activities, reduce chronic inflammation associated with sedentary behavior, and thus reduce the negative effects of sedentary behavior on cognitive function102,103,104. Finally, the RCS itself reflects a nonlinear relationship and thus could also imply that such “protective” trends emerge only at extreme sedentary levels; however, low to moderate levels may still be associated with an increased risk.

The present findings offer convincing arguments in favor of a relationship between sedentary time and HCD and establish a link with the obesity indicator WWI. Given that weight and WC can be obtained from a standard physical examination, the calculation of WWI is both economical and easy to implement in a clinical setting. In addition, the direct calculation of WWI via the formula eliminates the need for complex laboratory procedures, thereby increasing its utility for early detection of HCD risk. It is therefore recommended that clinical providers consider sedentary time control and WWI as a proven method of HCD prevention.

Conclusion

Based on this study, sedentary time was significantly and non-linearly associated with the incidence of HCD, with WWI playing a mediating role. This finding may provide valuable suggestions for the prevention and treatment of HCD and inspire healthcare professionals to rationalize sedentary time may reduce the risk of HCD by moderating WWI. However, these findings still require longitudinal studies.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of this study are multiple. Primarily, it is the first cross-sectional study to examine the association between sedentary time and HCD risk, and it incorporates obesity indicators for causal mediation analyses, thus providing new perspectives on the prevention and treatment of HCD. Second, although the DSM-V/NIA-AA criteria were not used directly, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and multi-dimensional assessment methods (including screening for comorbidities) were used to ensure the homogeneity of the study sample and to minimize the potential confounding factors such as depression and dementia. The data used in this study came from a comprehensive database containing a large sample of HCD patients, which improved the representation of the findings. Finally, the covariates in the model were statistically rigorously adjusted, enabling more reliable and convincing conclusions to be drawn.

Of course, there are some limitations to this study. The sedentary time was initially assessed through a self-report questionnaire, which may result in recall bias and cannot accurately reflect long-term sedentary behavior. Although self-reporting can reflect specific areas (such as occupational sedentary and recreational sedentary), its inherent subjectivity and reliance on subjects ' memory limit the accuracy of the measurement. Respondents may systematically underestimate long-term sedentary activities (such as screen time) or overestimate physical activity due to social desirability bias105. Secondly, in the current study, the accelerometer is the gold standard for objective measurement of sedentary behavior; however, accelerometers cannot distinguish different types of sedentary behavior, and it is time-consuming and expensive to apply them to large-scale clinical research. Thirdly, although there is a strong correlation between the MMSE score and the likelihood of cognitive decline106,107, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) appears to be more sensitive than MMSE in the diagnosis of early cognitive impairment108. Finally, since this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine the causal relationship between cognitive decline and sedentary behavior in hypertensive patients.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to H.J.

Abbreviations

- HCNF:

-

Hypertensive patients with normal cognitive function

- HCD:

-

Hypertensive patients with cognitive decline

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WWI:

-

Weight-adjusted-waist index

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- LVD:

-

Left ventricular diameter

- RVD:

-

Right ventricular diameter

- LAD:

-

Left atrial diameter

- RAD:

-

Right atrial diameter

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

- PA level:

-

Physical activity level

- ACEI/ARB:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor inhibitor

- CCBs:

-

Calcium channel blockers

References

Zhong, X. et al. A risk prediction model based on machine learning for early cognitive impairment in hypertension: development and validation study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1143019 (2023).

Snyder, E. C., Abdelbary, M., El-Marakby, A. & Sullivan, J. C. Treatment of male and female spontaneously hypertensive rats with TNF-α inhibitor etanercept increases markers of renal injury independent of an effect on blood pressure. Biol. Sex. Differ. 13, 17 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Body mass index mediates the relationship between the frequency of eating away from home and hypertension in rural adults: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional study. Nutrients 14, 1832 (2022).

Zhuo, X., Huang, M. & Wu, M. Analysis of cognitive dysfunction and its risk factors in patients with hypertension. Med. (Baltim). 101, e28934 (2022).

Qin, J. et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in patients with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens. Res. 44, 1251–1260 (2021).

Lv, S. et al. Association between intensity of physical activity and cognitive function in hypertensive patients: a case-control study. Sci. Rep. 14, 10106 (2024).

Jia, L. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in china: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public. Health. 5, e661–e671 (2020).

Nuijten, R. et al. Evaluating the impact of adaptive personalized goal setting on engagement levels of government staff with a gamified mHealth tool: results from a 2-Month randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 10, e28801 (2022).

Owen, N., Sparling, P. B., Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W. & Matthews, C. E. Sedentary behavior: emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85, 1138–1141 (2010).

Nasui, B. A. et al. Comparative study on nutrition and lifestyle of information technology workers from Romania before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 14, 1202 (2022).

Dillon, K. et al. Total sedentary time and cognitive function in Middle-Aged and older adults: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open. 8, 127 (2022).

Arundell, L., Fletcher, E., Salmon, J., Veitch, J. & Hinkley, T. A systematic review of the prevalence of sedentary behavior during the after-school period among children aged 5–18 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 13, 93 (2016).

Wheeler, M. J. et al. Sedentary behavior as a risk factor for cognitive decline? A focus on the influence of glycemic control in brain health. Alzheimers Dement. (N Y). 3, 291–300 (2017).

Park, Y., Kim, N. H., Kwon, T. Y. & Kim, S. G. A novel adiposity index as an integrated predictor of cardiometabolic disease morbidity and mortality. Sci. Rep. 8, 16753 (2018).

Tao, Z., Zuo, P. & Ma, G. Association of weight-adjusted waist index with cardiovascular disease and mortality among metabolic syndrome population. Sci. Rep. 14, 18684 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Association between weight-adjusted waist index with incident stroke in the elderly with hypertension: a cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14, 25614 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Association of weight-adjusted-waist index with incident hypertension: the rural Chinese cohort study. Nutr. Metabolism Cardiovasc. Dis. 30, 1732–1741 (2020).

Xiong, Y. et al. Association between weight-adjusted waist index and arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients: the China H-type hypertension registry study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and heart failure: results from National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2018. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, (2022).

Fang, H., Xie, F., Li, K., Li, M. & Wu, Y. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and risk of cardiovascular diseases in united States adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 435 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Body mass index and waist circumference combined predicts obesity-related hypertension better than either alone in a rural Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6, 31935 (2016).

Zhao, J. et al. J-Shaped relationship between Weight-Adjusted-Waist index and cardiovascular disease risk in hypertensive patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A cohort study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 17, 2671–2681 (2024).

Chae, J., Seo, M. Y., Kim, S. H. & Park, M. J. Trends and risk factors of metabolic syndrome among Korean Adolescents, 2007 to 2018. Diabetes Metab. J. 45, 880–889 (2021).

Qiu, X., Kuang, J., Huang, Y., Wei, C. & Zheng, X. The association between Weight-adjusted-Waist index (WWI) and cognitive function in older adults: a cross-sectional NHANES 2011–2014 study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2152 (2024).

Christakoudi, S. et al. A body shape index (ABSI) achieves better mortality risk stratification than alternative indices of abdominal obesity: results from a large European cohort. Sci. Rep. 10, 14541 (2020).

Du, C., Hsiao, P. Y., Ludy, M. J. & Tucker, R. M. Relationships between dairy and calcium intake and mental health measures of higher education students in the united states: outcomes from moderation analyses. Nutrients 14, 775 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. The association between sleep quality and psychological distress among older Chinese adults: a moderated mediation model. BMC Geriatr. 22, 35 (2022).

Bakker, E. A. et al. Correlates of total and domain-specific sedentary behavior: a cross-sectional study in Dutch adults. BMC Public. Health. 20, 220 (2020).

Hypertension, W. G. et al. of 2018 C. G. for the M. of 2018 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chinese J. Cardiov. Med. 24, 24–56 (2019).

Yu, Q. J. et al. Parkinson disease with constipation: clinical features and relevant factors. Sci. Rep. 8, 567 (2018).

Ji, T. et al. Management of malnutrition based on multidisciplinary team decision-making in Chinese older adults (3 M study): a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study protocol. Front. Nutr. 9, 851590 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. The age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index predicts post-operative delirium in the elderly following thoracic and abdominal surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 979119 (2022).

Brunner, E. J. et al. Midlife risk factors for impaired physical and cognitive functioning at older ages: a cohort study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 237–242 (2017).

Son, K. L. et al. Morning chronotype decreases the risk of Chemotherapy-Induced peripheral neuropathy in women with breast cancer. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37, e34 (2022).

Li, X., Xue, Q., Yi, X. & Liu, J. The interaction of occupational stress, mental health, and cytokine levels on sleep in Xinjiang oil workers: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 924471 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Genetic scores of smoking behaviour in a Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6, 22799 (2016).

Mezey, G. A., Máté, Z. & Paulik, E. Factors influencing pain management of patients with osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 11, 1352 (2022).

Zhang, M., Zhong, X., Jiao, H. & Shunxin, L. Association between sleep quality and cognitive impairment in older adults hypertensive patients in china: a case–control study. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1446781 (2024).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statist 6, (1978).

Frank, E. & HarrellJr Regression Modeling Strategies https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Durrleman, S. & Simon, R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat. Med. 8, 551–561 (1989).

Chang, Y. T. Physical activity and cognitive function in mild cognitive impairment. ASN Neuro. 12, 1759091419901182 (2020).

Merchant, R. A., Kit, M. W. W., Lim, J. Y. & Morley, J. E. Association of central obesity and high body mass index with function and cognition in older adults. Endocr. Connect. 10, 909–917 (2021).

Fonte, C. et al. Comparison between physical and cognitive treatment in patients with MCI and alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Albany NY). 11, 3138–3155 (2019).

Sugiyama, T., Hadgraft, N., Clark, B. K. & Dunstan, D. W. Owen, N. Sitting at work & waist circumference-A cross-sectional study of Australian workers. Prev. Med. 141, 106243 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Association between the Weight-Adjusted waist index and serum uric acid: A Cross-Sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 1–10 (2023).

Li, X., Wang, L., Zhou, H. & Xu, H. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 24, 266 (2023).

Zhou, W. et al. Positive association between weight-adjusted-waist index and dementia in the Chinese population with hypertension: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 519 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. The relationship between obesity associated weight-adjusted waist index and the prevalence of hypertension in US adults aged ≥ 60 years: a brief report. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1210669 (2023).

Geremia, R., Cimadon, H. M. S., de Souza, W. B. & Pellanda, L. C. Childhood overweight and obesity in a region of Italian immigration in Southern brazil: a cross-sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 41, 28 (2015).

Patnaik, L. et al. Effectiveness of mobile application for promotion of physical activity among newly diagnosed patients of type II Diabetes – A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Prev. Med. 13, 54 (2022).

Wang, Y. C., Lin, C. H., Huang, S. P., Chen, M. & Lee, T. S. Risk factors for female breast cancer: A population cohort study. Cancers (Basel). 14, 788 (2022).

Park, E. & Ko, Y. Trends in obesity and obesity-Related risk factors among adolescents in Korea from 2009 to 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 5672 (2022).

Kluding, P. M. et al. Activity for diabetic polyneuropathy (ADAPT): study design and protocol for a 2-Site randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 97, 20–31 (2017).

Ra, J. S. & Kim, H. Combined effects of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors on metabolic syndrome among postmenopausal women. Healthc. (Basel). 9, 848 (2021).

Rinkūnienė, E. et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in Middle-Aged Lithuanian men based on body mass index and waist circumference group results from the 2006–2016 Lithuanian high cardiovascular risk prevention program. Medicina 58, 1718 (2022).

Chang, Y. et al. Total sitting time and sitting pattern in postmenopausal women differ by Hispanic ethnicity and are associated with cardiometabolic risk biomarkers. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e013403 (2020).

You, Y. et al. The association between sedentary behavior, exercise, and sleep disturbance: A mediation analysis of inflammatory biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 13, 1080782 (2022).

Whitaker, K. M., Pereira, M. A., Jacobs, D. R., Sidney, S. & Odegaard, A. O. Sedentary Behavior, physical Activity, and abdominal adipose tissue deposition. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 450–458 (2017).

Huang, Z., Liu, Y. & Zhou, Y. Sedentary behaviors and health outcomes among young adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Healthc. (Basel). 10, 1480 (2022).

Lee, W., Kang, M. Y., Kim, J., Lim, S. S. & Yoon, J. H. Cancer risk in road transportation workers: a National representative cohort study with 600,000 person-years of follow-up. Sci. Rep. 10, 11331 (2020).

Allison, M. A., Jensky, N. E., Marshall, S. J., Bertoni, A. G. & Cushman, M. Sedentary behavior and adiposity-associated inflammation: the Multi-Ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 42, 8–13 (2012).

Farhadnejad, H. et al. High dietary and lifestyle inflammatory scores are associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease in Iranian adults. Nutr. J. 22, 1 (2023).

Fischer, C. P., Berntsen, A., Perstrup, L. B., Eskildsen, P. & Pedersen, B. K. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein are associated with physical inactivity independent of obesity. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 17, 580–587 (2007).

Lindheim, L. et al. Alterations in gut Microbiome composition and barrier function are associated with reproductive and metabolic defects in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A pilot study. PLoS One. 12, e0168390 (2017).

Jobira, B. et al. Obese adolescents with PCOS have altered biodiversity and relative abundance in Gastrointestinal microbiota. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e2134–e2144 (2020).

Davies, K. B. et al. Physical activity and sedentary time: association with metabolic health and liver fat. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 51, 1169 (2019).

Ando, S., Koyama, T., Kuriyama, N., Ozaki, E. & Uehara, R. The association of daily physical activity behaviors with visceral fat. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 14, 531–535 (2020).

Vaara, J. P. et al. Accelerometer-Based sedentary Time, physical Activity, and serum metabolome in young men. Metabolites 12, 700 (2022).

Li, D. et al. Sedentary lifestyle and body composition in type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 8 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Waist-to-weight index and cognitive impairment: Understanding the link through depression mediation in the NHANES. J. Affect. Disord. 365, 313–320 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Joint association of weight-adjusted waist index and serum cotinine levels with systemic inflammatory index in adults. BMC Public. Health. 25, 2051 (2025).

Xu, W., Yue, S., Wang, P., Wen, B. & Zhang, X. Systemic inflammation in traumatic brain injury predicts poor cognitive function. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 10, e577 (2022).

Marsland, A. L. et al. Brain morphology links systemic inflammation to cognitive function in midlife adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 48, 195–204 (2015).

Shetty, A. K. et al. Monosodium luminol reinstates redox homeostasis, improves cognition, mood and neurogenesis, and alleviates neuro- and systemic inflammation in a model of Gulf war illness. Redox Biol. 28, 101389 (2020).

Perry, V. H., Nicoll, J. A. R. & Holmes, C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 193–201 (2010).

Huang, D. et al. Evaluation on monoamine neurotransmitters changes in depression rats given with sertraline, meloxicam or/and caffeic acid. Genes Dis. 6, 167–175 (2019).

Zhenyukh, O. et al. Branched-chain amino acids promote endothelial dysfunction through increased reactive oxygen species generation and inflammation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22, 4948–4962 (2018).

George, A. K. et al. Exercise mitigates alcohol induced Endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated cognitive impairment through ATF6-Herp signaling. Sci. Rep. 8, 5158 (2018).

Murray, K. N. et al. Systemic inflammation impairs tissue reperfusion through endothelin-dependent mechanisms in cerebral ischemia. Stroke 45, 3412–3419 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Association between healthy lifestyle and frailty in adults and mediating role of weight-adjusted waist index: results from NHANES. BMC Geriatr. 24, 757 (2024).

Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Caille, P. & Terracciano, A. An examination of potential mediators of the relationship between polygenic scores of BMI and waist circumference and phenotypic adiposity. Psychol. Health. 35, 1151–1161 (2020).

Gill, D. et al. Risk factors mediating the effect of body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio on cardiovascular outcomes: Mendelian randomization analysis. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 45, 1428–1438 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Effects of smoking on regional homogeneity in mild cognitive impairment: A Resting-State functional MRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 572732 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Smoking alters effective connectivity of resting-state brain networks in mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 105, 893–903 (2025).

Deal, J. A. et al. Relationship of cigarette smoking and time of quitting with incident dementia and cognitive decline. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68, 337–345 (2020).

Brennan, P. L., Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H. & Schutte, K. K. History of drinking problems diminishes the protective effects of within-guideline drinking on 18-year risk of dementia and CIND. BMC Public. Health. 21, 2319 (2021).

Hagger-Johnson, G. et al. Combined impact of smoking and heavy alcohol use on cognitive decline in early old age: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 203, 120–125 (2013).

Yen, F. S., Wang, S. I., Lin, S. Y., Chao, Y. H. & Wei, J. C.-C. The impact of heavy alcohol consumption on cognitive impairment in young old and middle old persons. J. Transl Med. 20, 155 (2022).

Ungvari, Z. et al. Sleep disorders increase the risk of dementia, alzheimer’s disease, and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis. Geroscience 47, 4899–4920 (2025).

Lim, A. S. P., Kowgier, M., Yu, L., Buchman, A. S. & Bennett, D. A. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep 36, 1027–1032 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Association between sleep duration and cognitive decline. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2013573 (2020).

Lazar, R. M. et al. A primary care agenda for brain health: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Stroke 52, e295–e308 (2021).

Desideri, G. & Bocale, R. Correlation between cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 23, E73–E76 (2021).

Huang, L. Y. et al. Association of occupational factors and dementia or cognitive impairment: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 78, 217–227 (2020).

Maeir, T. et al. Cognitive retraining and functional treatment (CRAFT) for adults with cancer related cognitive impairment: a preliminary efficacy study. Support Care Cancer. 31, 152 (2023).

Vemuri, P. et al. Association of lifetime intellectual enrichment with cognitive decline in the older population. JAMA Neurol. 71, 1017–1024 (2014).

Fallahpour, M., Borell, L., Luborsky, M. & Nygård, L. Leisure-activity participation to prevent later-life cognitive decline: a systematic review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 23, 162–197 (2016).

Liang, H. et al. Excessive sedentary time is associated with cognitive decline in older patients with minor ischemic stroke. J. Alzheimers Dis. 96, 173–181 (2023).

Kurita, S. et al. Cognitive activity in a sitting position is protectively associated with cognitive impairment among older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19, 98–102 (2019).

Hassani, S. & Gorelick, P. B. What have observational studies taught Us about brain health? An exploration of select cardiovascular risks and cognitive function. Cereb. Circ. Cogn. Behav. 7, 100367 (2024).

Ravichandran, S. et al. Age-dependent nonlinear relationship between hypertension and hippocampal volume in sedentary women with lower educational attainment. J. Educ. Health Promot. 14, 183 (2025).

Saklıca, D., Vardar-Yağlı, N., Ateş, A. H. & Yorgun, H. Does cognitive function affect functional capacity and perceived fatigue severity after exercise in patients with coronary artery disease? Physiother Res. Int. 29, e2139 (2024).

Sartori, A. C., Vance, D. E., Slater, L. Z. & Crowe, M. The impact of inflammation on cognitive function in older adults: implications for healthcare practice and research. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 44, 206–217 (2012).

Healy, G. N. et al. Measurement of adults’ sedentary time in Population-Based studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 41, 216–227 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Hearing impairment with cognitive decline increases All-Cause mortality risk in Chinese adults aged 65 years or older: A Population-Based longitudinal study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 865821 (2022).

Fraser, G. E., Singh, P. N. & Bennett, H. Variables associated with cognitive function in elderly California Seventh-day Adventists. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 1181–1190 (1996).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal cognitive Assessment, moca: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the participants in this study for their help with this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82474422).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ and DL were the main coordinators of the project and were responsible for the design of the study. The manuscript of this article was written by MZ. SL supervised data collection. MZ and CW were involved in data collation and analysis. H.J was responsible for critical revision of the article, final approval of the article, and collection of funds. All authors contributed intellectually to this manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Ethics Committee has granted ethical approval. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods have been carried out according to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Liu, D., Lv, S. et al. Relationship between sedentary time and cognitive decline in hypertensive patients-mediating role of the weight-adjusted waist circumference index. Sci Rep 15, 39531 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23395-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23395-z