Abstract

Selective adsorption of anions from aqueous solutions is essential to many industrial and remediation applications. A novel anion sorbent was developed using hybrid glycoboehmite (GB) synthesized from 1,4-butanediol and potassium hydroxide mineralizer. GB materials were further functionalized through Ni2+ adsorption from aqueous solutions. The adsorption capacity of GB for Ni2+ was found to be 2 to 5 times greater than that for Mg2+ or Ca2+, and 12 times higher than that of simple boehmite normalized to the surface area. Relative to GB, nickel-functionalized GB (Ni-GB) exhibits favorable adsorption properties for arsenate and iodide with much improved partitioning coefficient values (KD) of ~ 6400 and 43 mL/g respectively. Experimental characterization along with classical and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations offers insight into the ion adsorption mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contaminant capture is a critical function for agricultural protection, water purification, industrial site remediation, and radiological materials processing1,2. Sorbent materials—including a large variety of metal oxides—are employed for the specific capture of ionic contaminants. Metal oxides (e.g., iron oxides, rutile, and perovskites), natural or synthesized clays, and nanomaterial sorbents have long been a research focus to remove or isolate aqueous contaminants3,4,5. Nuclear waste disposal concepts utilize engineered barrier systems containing bentonite clays, where the low permeability and high sorption capacity are ideal for immobilizing radionuclides released from nuclear waste6,7,8. The negative charge on bentonite particles reduces their effectiveness at sorbing anions such as I−, which contributes significantly to the total dose release from a deep geologic repository9. 129I, with a half-life of 15.7 million years, is a particular concern for spent nuclear fuel disposal due to its high aqueous solubility, mobility, and toxicity10. Performance assessment calculations show that even a small retention capability for iodine can make a substantial difference in total dose predictions11,12. Removal of anionic pollutants including arsenic from the environment is difficult and expensive1. Arsenic concentrations increase in the surface and groundwater due to the presence of mine and refinery wastes, wastewater sludge, agrochemicals, ceramic industries, and coal fly ash. In 2012 arsenic was found to be one of the six world’s worst contaminants; exposure symptoms include skin lesions and cardiovascular disease13.

The sorption behavior of metal oxides is broadly related to an ion’s propensity to form surface complexes, to exchange with other ions, or to bind to organically functionalized surfaces5,14. Boehmite (AlOOH) is a layered aluminum oxyhydroxide mineral that is earth abundant and easily synthesized15,16. The layer structure is based on edge linked Al-O6 octahedra with an interlayer structure normal to the unit cell b direction composed of hydroxyl groups that exhibit a particularly strong zig-zag H-bonding structure17,18,19. Boehmite cation adsorption behavior is related to the surface charge of the material and the resulting electrostatic effects. The surface of boehmite is amphoteric with an isoelectric point of 8.620. Boehmite has served as a regenerable adsorbent for divalent cations including Mg2+, Cu2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, and Co2+.21 For transition metals, the mechanism of adsorption was proposed via exchange with the hydronium component of the surface hydroxyl groups. 21 Most ions have a removal rate below 20%, with the exception of Pb2+, and Cu2+, which are between 20 and 30% in acidic conditions21. The positive surface charge of boehmite below the isoelectric point of 8.6 inhibits cationic adsorption through electrostatic repulsion, where the removal rate for Ni2+ is less than 1%22.

Organically modified, hybrid derivatives of boehmite can be synthesized with glycol solvent methods to form a series of glycoboehmite (GB) nanoparticle materials23,24,25. In these phases, the interlayer zig-zag hydrogen bonding structure of boehmite is altered through the covalent substitution of glycol molecules for a fraction of the interlayer hydroxyl groups. Layer expansion was previously reported for a range of glycol chain lengths (C2-C6)24,25. Recent work shows that layer expansion of 1,4-butanediol intercalated material can be up to 18 Å, greater than that previously reported26,27. The colloidal surface charging behavior of these materials was only reported recently by Bell et al.26, showing a shift in the isoelectric point from 8.6 in aqueous boehmite to ≈6 in GB. The origin for the altered surface charging properties remains a key question, as glycol molecules are neutral species with protonation behavior similar to alcohols. The interlayer structure of GB materials was modeled using density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) methods, finding that the intercalated glycol interlayers can develop a hydrophilic bilayer-type structure under favorable conditions28.

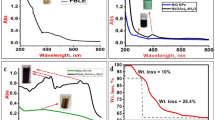

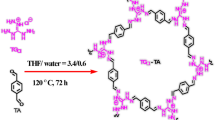

Ion adsorption behavior of these GB materials have not been reported to our knowledge. Here, the specific adsorption behavior of Mg2+, Ca2+, and Ni2+ cations on 1,4-butanediol GB is presented. Metal uptake by GB was measured by liquid and solid quantification techniques, shown in Fig. 1 along with the reaction scheme. Ni2+ showed specific functionalization in contrast to the behavior of Mg2+ and Ca2+ which have low uptake activity. Surface chemical and structural characterization of the Ni2+ modified GB (Ni-GB) is presented, as well as digestion and solution analysis of the Ni2+ adsorption capacity. Classical and ab initio molecular dynamics (CMD and AIMD, respectively) modeling of the GB structure is used to investigate the factors responsible for the altered surface charging and ionic adsorption behavior of Ni-GB. The properties of Ni-GB materials are reported with regard to the modification process for the particulate material and its application for capture of I− and AsO43− from solution. Surprisingly, the Ni-GB material is found to be a novel anionic getter material suitable for incorporation into an engineered barrier system (EBS) design in nuclear waste disposal or as an environmental contaminant adsorbent.

Results

The GB material shows a shift in isoelectric point from aqueous synthesized boehmite20,26, indicating that anomalous surface chemistry may arise from the glycol functionalization of the surface and the layer structure expansion28. In Part 1, measurements are presented to improve the understanding of the surface structure in GB through XPS and cation uptake by total acid digestion of the treated GB along with surface area measurements. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy are used to characterize physical changes in surface area and molecular structures, and surface charge is characterized with pH titration using zeta potential measurements. In Part 2, the results of batch sorption experiments on the capture of anionic contaminants are presented. Finally, MD simulations are described to model the uptake of cations (Ni2+, Ca2+, and K+) by GB and subsequent anion (Cl−, I−) uptake by the cation-modified materials.

MD simulations are described to model the uptake of Ni2+ by GB and subsequent anion uptake.

Part 1. Adsorption of divalent cations by GB

GB composition

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Figure S1) and carbon content from combustion analysis (Galbraith Laboratories, Inc.) were used to measure the surface composition of GB materials and the electron configuration of the organic materials. The analysis interpreted the composition of GB as related to the Al, O, K, and C within the sample. Table 1 shows that GB is dominated by the presence of Al and O as would be expected from the base structure of AlOOH. Significant C content is related to the intercalated glycol. Further breakdown of the carbon and oxygen composition is provided in Table S1 as the degree of CH2 and C-O bonds, with C-O relating to covalent bonding of glycols with the Al-O structures or as terminal -OH groups (the glycols are not bonded across the interlayer distance).

The C content of 16.46% in Table 1 represents the substitution of interlayer -OH groups with glycols, as previously discussed by Inoue, et al.24,29 That characterization stated a maximum degree of substitution by glycol at 33%, and a measured fraction of 0.31 site substitution24. Based on a comparison of atom ratios from XPS with hypothetical diol loadings (Table 1), a site substitution of approximately 0.15 is the best match to the XPS data and C content from combustion analysis. Including 0.01 K per AlOOH formula unit yields a mol% K in agreement with XPS. The presence of K is a result of the use of KOH as a mineralizer in the glycothermal synthesis and indicates that residual KOH could be present in the interlayer region.

Divalent metal cation adsorption

GB materials were examined for their adsorption behavior with divalent cations Mg2+, Ca2+, and Ni2+ as a novel property of these hybrid materials (Fig. 1). ICP-OES was used to measure the cation concentration in MgCl2, CaCl2, and NiCl2 solutions after reaction with GB shown in Table S2. The solid materials were then analyzed by ICP-OES following total acid digestion. XRF was also used to characterize compositional variations in the initial and ion-exposed materials (Table S3). It is shown that Ni2+ has a specific adsorption above that of Mg2+ and Ca2+ in contrast to an electrostatic mechanism, and that K+ trace material is present in the product based on the synthesis approach.

The uptake of Mg2+, Ca2+, and Ni2+ was characterized by full compositional analysis of the solid phase using acid digestion with HF. Table 2 shows the compositional analysis by ICP-OES after material digestion. Similar to the cation exchange experiments (Table S2), more Ni2+ reacted with GB than Mg2+ or Ca2+. Digestion analysis also indicates a similar amount of K+ remaining regardless of divalent metal reaction, which is significantly less than the amount of K+ in unreacted GB. Solution depletion measurements for GB in divalent metal cation solutions are summarized in Table S2, along with Ni2+ uptake for boehmite.

Boehmite is not known to be highly active for Ni2+ adsorption. Strathmann and Myneni22 examined Ni2+ adsorption on boehmite, finding that Ni2+ adsorbs as an inner-sphere, bidentate mononuclear complex with surface aluminol groups. Their calculation of adsorption coverage over the boehmite material was stated to be low, at 0.031 mmol/m2 in 10 mM Ni2+ solution and 0.14 mmol/m2 in 100 mM Ni2+ solution as the highest case22. Both values are far below monolayer coverage, suggesting that Ni2+ adsorption is not highly favored thermodynamically. The relatively higher Ni2+ uptake in GB (9.10 mg/g) compared to boehmite (0.32 mg/g) suggests that organic modification of the material structure or the presence of altered surface sites plays a role in this behavior. XRF material composition in mole percent is shown in Table S3 and further supports the metal uptake and material digestion analysis and release of K+.

Overall, there is a clear trend in adsorbed cation behavior: Ni2+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. Divalent cation uptake by GB is not a simple cation exchange process since the amount of K+ released is constant regardless of the divalent cation. Further characterization of the adsorption process through kinetic evaluation of uptake will be the focus of subsequent work.

Surface area

The surface areas of boehmite and the GB materials were measured to determine if exfoliation affects anion sorption capability. The similarity in BET surface areas between unreacted and metal-functionalized GB (Table 2) indicate that K+ release and divalent cation adsorption do not affect the particle surface area. The unreacted boehmite material has a higher surface area (297.5 m2/g) yet it has a lower Ni2+ uptake when compared to GB materials. We conclude that the microstructure of the materials does not contribute to ion uptake.

X-ray diffraction

Previous work on GB shows a significant expansion of the interlayer spacing over that of the boehmite precursor phase, thereby requiring low 2θ angle XRD measurements in order to obtain accurate observation of the largest d-spacings in the unit cell which are typically related to the interlayer distance between the AlOOH layers26. Fig. 2 presents the powder XRD patterns of GB materials, showing a broad, low-angle reflection at ~ 7.5º 2θ. The unintended benefit of this residual boehmite phase is that it underscores the significant shift of the (020)b peak at 14.5° to that of (020)GB at 7.5°, reflecting the significant impact of the intercalated glycol into the GB structure. The main observation of the XRD analysis for the stacked series of GB samples is that there is little change in the (020)GB peak location, characterized by a d-spacing of 11.7 Å for the metal-functionalized materials relative to the unreacted GB baseline material. Table S4 shows average d-spacing values, which reveal nearly identical outcomes in all functionalized materials as compared to baseline GB. While this result appears inconclusive in that there is not an evident change in the interlayer spacing during metal functionalization, it should be noted that these samples were run as dry powders, and any impact of hydration to the interlayer distance would not be reflected in this result. In prior work by Inoue et al.24, the interlayer spacing is lower than in the work of Bell et al.26 and shows variance among reported studies. Water may play an important role in the additional expansion of the interlayer and the overall value of the interlayer distance may be impacted. Coupling this result with the previous observations for composition of unreacted and functionalized GB, the XRD results suggest that the interlayer spacing for dry GB powders is dictated primarily by the incorporation of the organic glycol molecule regardless of cation species present.

FT-IR

FT-IR data on the GB and Ni-GB were taken to compare differences in IR spectra with K+ (initial) and Ni2+ as the predominant cations (Fig. 3). A detailed discussion of peak assignments in boehmite and GB can be found elsewhere28. The majority of the characteristic peaks between the initial GB and Ni-GB materials appear unchanged in both peak location and intensity. The greatest difference between the two materials lies in the broad peak centered at 3300 cm− 1, and the peak at 1640 cm− 1. These peaks are typical of hydrogen bonding within -OH groups. Surface hydroxyl groups are characterized in boehmite at 1635 cm− 1, whereas the GB material has a weak peak at 1637 cm− 1. The adsorption of Ni2+ thus appears to relate to the H-bonding character of the GB material.

Siahpoosh et al. examined Ni2+ adsorption on gamma alumina and suggested that surface hydroxyl bands at 2104, 1084 and 789.8 cm− 1 disappear when Ni2+ adsorbs and coordinates with these surface -OH species30. Siahpoosh et al. also observed a weak red shift for the predominant –OH stretch at 3473 to 3469 cm− 130. In GB, there are no characteristic bands for surface –OH that show a significant shift or disappear between the two samples. Our work shows the greatest change at 3250 cm− 1 and above, where the hydrogen bonding peak increases with Ni2+ adsorption. The intensity of the band at 1640 cm− 1 also increases. The greater intensity of the bands related to hydrogen bonding among –OH groups may indicate that there is more vibrational mobility in those groups, or that the hydration sphere of the Ni2+ cations is involved with this adsorption mode. This suggests that adsorption of Ni2+ is based on hydrogen bonding in these materials. The presence of the glycol groups within and at the surface appears to alter the formation of coordination groups for Ni2+ adsorption without the formation of normal inner sphere model complexes30.

Zeta potential

Metal oxide adsorption of divalent ions as inner or outer sphere species is characterized by shifts in electrostatic charge as a function of pH and can be characterized with zeta potential measurements. Zeta potential titrations were taken of unreacted GB and Ni-GB. The pH vs. zeta potential titrations are plotted in Fig. 4, presenting the average results of 4–5 sample measurements with standard deviations. These results show the significant variation in surface charging with Ni2+ functionalization. Our results contrast with that of aqueous phase synthesized boehmite materials. Reported results for boehmite formed under aqueous and hydrothermal approaches, find isoelectric point (IEP) values of 8.5 to 9.2 as typical ranges for these materials20,31,32.

GB was recently investigated for its colloidal charging behavior, finding that there is a significant shift in charge development contrasted to boehmite. GB exhibits an isoelectric point (IEP) of 5.5 with a relatively linear slope in its amphoteric charging behavior, which is believed to occur due to the presence of bound butanediols on the particle surface26. The isoelectric point is shifted to a pH of 6.5 in Ni-GB. The shape of the curve is also altered from the linear charging profile in GB. Above the IEP, there is a more rapid development of negative surface charge between pH 7 to 8.5, with a higher magnitude of negative charging up to pH 10. It follows that the addition of Ni2+ cations raises the IEP as would be expected for surface adsorption22. Islam et al.33 studied Ni2+ adsorption on boehmite, finding pH dependence that increased above pH 8, where Ni2+ species begin to hydrolyze to NiOH+ solution species. Islam et al. conclude that surface complexation can be modeled with two inner sphere complexes and an outer sphere complex33. In the Ni-GB pH profile, the additional positive surface charge relative to GB reflects the presence of Ni2+ cations at the surface. At approximately pH 8, Ni2+ in solution begins to form the hydrolysis products Ni(OH)+ and ultimately the hydroxide Ni(OH)2. The more rapid development of a negative zeta potential value as pH increases reflects the formation of the Ni hydrolysis species on the adsorbed surfaces.

Part 2. Arsenate and iodide sorption

The ability of Ni-GB to sorb anionic contaminants such as I− and AsO43− was also evaluated. Without pH adjustment, significant increase in I− and AsO43− sorption was seen for Ni-GB compared with unreacted GB, as shown in Table 3. Arsenate KD in Table 3 is significantly larger than typical values for soils and sediments34, suggesting that Ni-GB would preferentially bind arsenate in subsurface environments. While the sorption capacity for I− is not as high as AsO43−, there is still a significant increase in I− uptake between GB and Ni-GB. Table 3 also shows a significant increase in I− sorption in Ni-GB compared to Ca-GB and Mg-GB, along with a significant drop in pH for Ni-GB. These materials have a similar structure based on XRD and FTIR results, so we conclude that anion adsorption in GB is controlled by the type of cation present and solution pH. Additionally, the significant increase for Ni-GB suggests that these anions interact directly with occupied d orbitals in Ni2+.

Table 4 shows I− sorption values for reactions that were pH adjusted to 7 (+/-1.0) and includes a comparison with reported KD values by other materials. As shown in Figure S2, the pH was adjusted to neutral using KOH and HNO3, once after water addition and again 24 h later before they were spiked with the I− standard. The reactions were then allowed to equilibrate, and a final pH was measured of the solution after centrifugation (Figure S2). After the pH adjustment, solution pH values varied from 6.42 for Ni-GB to 7.96 for unreacted GB. Notably, unreacted GB showed modest I− uptake at lower pH (7.96) compared to no measured uptake at higher pH (9.67). For Ni-GB, pH adjustment resulted in a 41% increase in I− sorption even though the final pH readings were similar (6.42 vs. 6.28). The similarity in I− uptake in unreacted and Ni-boehmite might suggest that a different anion adsorption mechanism controls uptake in these materials. Ni2+ and I− can only adsorb to external boehmite surfaces and edges, while these ions could adsorb to GB at interlayer sites.

The iodide KD values in Tables 3 and 4 are significantly larger than those reported for bentonite35, which is expected based on the permanent negative layer change in smectite clays found in the majority of bentonites. However, iodide uptake is significantly larger in surfactant-modified clays36. Anionic clays (layered double hydroxides or LDHs) in their calcined form have shown iodide uptake similar to or greater than our results37. However, the presence of carbonate anions in the LDH interlayers significantly diminishes iodide uptake38. A comprehensive study was done on I− uptake by various LDH phases via coprecipitation, anion exchange and reconstruction tested for various Ca, Mg, Al, and Fe LDHs with different metal ratios and anions37. Iodide was incorporated into the material less than iodate, probably due to differences in the charge density, size and configuration of the IO3− and I− ions. This work concluded that LDHs could be considered as iodine sorbents for remediation or short-term storage, but they are not suitable for long term storage of radioactive iodine due to their low thermal stability and easy iodide release on contact with Milli-Q water and brine39. We postulate that the high KD value of Ni-GB for iodide can probably be attributed to the formation of LDH-like molecular clusters on material surfaces or interlayers.

MD simulations

The synthesized materials have an approximate loading of 0.66 diols/u.c. (based on XPS results, Table 1) and a layer spacing of 11.7 Å for both the as-synthesized (containing K+) and Ni-functionalized samples (based on XRD results, Fig. 2). As seen in Table S5, layer spacings of the simulated materials at 0.5 diols/u.c. loading are slightly larger than the experimental value with water present (12.7 for K+, 12.6 Å for Ni2+), but in good agreement with the dry NiCl2 model (12.2 Å). Based on these comparisons, it seems that the experimental samples do not contain water in the interlayer, but this is difficult to verify experimentally. Accompanying snapshots from CMD simulations (Figures S3-S5) illustrate the trends in layer spacings seen in Table S5, and ion pairing between Ni2+ and Cl− ions is shown in Figure S6.

Figure 5 shows representative snapshots of equilibrated 3D-periodic supercells from canonical ensemble AIMD simulations at 25 °C of GB including CaCl2 and KCl, water molecules, as well as NiCl2 and NiI2, in the interlayer space. Simulations show that the metal ions are initially immobilized in the interlayer by forming covalent bounds with neighboring oxygen atoms from butanediols (and water molecules), without significantly altering the structure (simulated XRD patterns are shown in Figure S7). This finding appears consistent with XRD characterization of Ni-functionalized GB, which shows little change compared to butanediol-functionalized GB without Ni. Cl− and I− anions also appear to form covalent bonds with Ca and Ni in the GB-CaCl2, GB-NiCl2, and GB-NiI2 simulations.

Snapshots from AIMD simulations at 25 °C of 3D-periodic supercells of butanediol-functionalized GB including (a) CaCl2, (b) KCl, (c) NiCl2 and (d) NiI2, and water molecules in the interlayer space. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. Color legend: Al, cyan; C, brown; Ca, magenta; Cl, green; H, white; I, yellow; K, blue; Ni, grey; O, red.

Conclusions

This work demonstrates the novel Ni2+ ion adsorption behavior of organically modified GB. In contrast to boehmite minerals, which have a low thermodynamic driving force for adsorption of Ni2+, these hybrid materials demonstrate unique surface charging and adsorption behavior22. Normalizing for surface area, GB has 12 times higher sorption affinity for Ni2+ compared to boehmite. GB shows a release of K+ used in the synthesis process into aqueous environments in a non-specific manner and specifically adsorbs Ni2+ over that of Group II cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+).

Structural and spectroscopic property measurements of Ni-GB do not show changes between the unreacted and functionalized GB materials. Surface charging characteristics are shifted from the initial materials proving that electrostatic attraction is not the sole factor in modification and does not appear to consist of specific ion adsorption on surface sites. The anion adsorption process is theorized to be related to the uptake of solvent and cations within the diol-intercalated structural layers. Based on atomic ratios obtained from XPS data, the degree of diol site substitution is approximately 0.15 per AlOOH formula unit. Molecular modeling was applied to simulate the interlayer structure of functionalized GB for a range of diol loadings. Both the arrangement of diols and local structure of interlayer ions depends on the degree of diol substitution.

Importantly, Ni-GB demonstrates strong affinity to capture aqueous anionic species including I− and AsO43−, at a relatively low pH (less than 7). Differences in the partitioning coefficient (KD) between GB and Ni-GB show a significant increase for both anionic contaminants, proving a strong capacity for solution applications. This trend is evident in both the unadjusted and adjusted pH experiments; when Ni-GB is present, the pH decreases to about 6.4, regardless of whether it was initially adjusted to 7 or not. Additionally, although the final pH values are comparable, Ni-GB exhibited a higher I− sorption KD when the pH was initially adjusted to 7, compared to the unadjusted tests. GB also showed an increase in sorption when the pH was adjusted. Boehmite has appreciable I− sorption during the pH adjusted batch experiments; actually, it removed more I− than the GB alone. However, there was only a small increase in I− sorption when boehmite was Ni-functionalized compared with the much larger increase in I− sorption when GB was Ni-functionalized. Arsenate uptake is also enhanced at lower pH. Unreacted GB at pH 9.4 shows very little arsenate uptake. For Ni-GB, the pH is lowered to 7.1 when immersed in water, resulting in exceptional uptake (KD > 6400). While boehmite has a much higher surface area than GB; when surface area is factored in Ni-GB has a significantly higher KD than boehmite or Ni-boehmite. We conclude that both Ni-modification and lower pH contribute to increased anion sorption, and these factors may be related. This work demonstrates the anion sorption properties of a new high surface area sorbent material. Future studies will evaluate adsorption reversibility, pH effects, and material interaction with clay minerals.

Methods

GB synthesis

A Parr Instruments stainless steel reaction vessel (600 mL capacity) was loaded with 10 g of gibbsite (Al(OH)3, Micral Corporation) and 0.31 g KOH with 200 mL of 1,4 butanediol. The vessel was sealed and vacuum applied to the exhaust port for over 20 min to remove entrapped air. Next N2 gas (UHP) was bubbled through the chamber using the sampling tube for > 20 min to create an inert atmosphere. The sealed vessel was heated under stirring using a 2-hour ramp to 250 °C, followed by a hold of 24 h at 250 °C before cooling to ambient temperature. The white precipitate was recovered using four cycles of centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 5 min, with resuspension in isopropyl alcohol.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization of surface species

Flake based coatings were prepared by dispersion of the GB sample in 2-butanol under ultrasonic mixing and disaggregation, using an ultrasonic bath for 1 h. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 30 min to remove large aggregates and provide a stable turbid suspension of nanosheet materials. A Si wafer was cut to a size of 1 cm by 10 cm and placed in a Teflon beaker at an angle of 25°. The GB suspension was added to the beaker to coat the wafer and allow for film formation by ambient drying of the suspension in the Teflon tube. Drying occurred over 3 days to provide a uniform film over the Si wafer sample. The sample was then utilized for surface measurement in the XPS instrument. XPS was performed using a Kratos Axis Supra XPS system with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. A survey spectrum and high resolution of certain elements were taken over 5 points on one sample, with the data being averaged together. The size of the analyzed area was 950 μm x 450 μm. Base pressure during analysis was 2.3 × 10− 9 torr and the electron emission angle was at 54.7° with an active charge neutralizer. XPS data was analyzed using CasaXPS software (version 2.3.26, http://www.casaxps.com/) with the Kratos relative sensitivity factors set to F 1s at 1. The C 1s signal at 285 eV was used as an internal reference for peak positions for all points.

M(II)-functionalized boehmite and GB

GB and boehmite were heated to 100 °C for 2 h before any treatments to remove any excess liquid. After heating, the dehydrated material underwent surface modification using 0.01 M NiCl2 (Sigma Aldrich, 98%), MgCl2 (Thermo Scientific, 99.0-102.05), or CaCl2 (Sigma Aldrich, 97%). The dehydrated material was added to a NiCl2, MgCl2, or CaCl2 solution at a concentration of 0.016 g/mL in centrifuge tubes. After 24 h on a shaker table the modified material was centrifuged and excess NiCl2, MgCl2, and CaCl2 was decanted, yielding functionalized GB, which was then dried in a 60 ºC oven. The Ni-GB material resulted in a color change from white to a pale green (Fig. 1).

Nickel, magnesium, and calcium uptake and cation exchange were determined by collecting the decanted solution after reaction with GB as described above. The liquids were diluted and acidified for analysis using a Perkin Elmer Optima 8000 Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) and measured along with standard elemental reference material (SPEX CertiPrep- Assurance standard 23).

Compositional analysis

For compositional analysis, 0.5 g of various GB materials were digested in 5 mL concentrated hydrofluoric acid (Fisher, 47–51%). Depending on material, samples took several days to a week to digest fully. Digestions were brought to 50 mL with DI water without further dilution to keep solvation optimal. Elemental concentrations were then measured using a Perkin Elmer Avio 500 ICP-OES. ICP-OES background-corrected emission lines were chosen for evaluation by their optimal performance for each element. Samples were analyzed along with standard elemental reference materials (Inorganic Ventures).

Braunauer–Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area

Surface area measurements by N2 adsorption were completed on the GB materials using a Tristar 3000 surface area and porosimetry analyzer (Micromeritics). To remove excess CO2 the samples were first degassed with a 30 °C hold for 10 min and additional 60 °C soak for 24 h.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

XRF measurements were performed using a Bruker M4 micro-XRF system employing a Rh X-ray source, a polycapillary focusing optic (25 mm spot size) and a Silicon Drift X-ray detector. XRF spectra were collected for 30 s and quantification was performed within the Bruker Esprit M4 software (version 2017, https://www.bruker.com) for determination of wt% and mol% values.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

XRD patterns were collected using a Siemens q-q θ-θ D500 diffractometer equipped with a sealed-tube Cu anode X-ray source, a diffracted-beam graphite monochromator, and a scintillation detector. Small slits (0.3º) were employed to enable low angle measurements (4º to 60º 2θ) with a step-size of 0.04º and count time of 30 s per step.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Spectra were obtained of dried GB powders using a Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) using a Smart iTR ATR sample accessory. Dried powder was fixed in the measurement accessory per instrument operation procedures. IR spectra were obtained from 128 scans of the background and of the sample.

Zeta potential measurements

A Stabino Particle Charge analyzer instrument (Particle Metrix) was used to measure the zeta potential of GB suspensions, with a 400-micron piston element for measurement. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich USA and used as received. Solutions of 10− 3 M KNO3 were used as background electrolyte, with titrants of 0.025 M concentration for pH adjustment, using HNO3 and KOH (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS grade). Small quantities of powder (0.05 g) were added to 20 mL of electrolyte solution and dispersed using treatment for five minutes in an ultrasonic bath, to create a weakly opaque suspension. The pH sensor in the Stabino instrument was calibrated against standard pH solutions (pH 4, 7, and 10) and the zeta potential was calibrated using the Stabino zeta standard prior to sample measurements (+ 50 mV). Samples were first adjusted to pH 9 using 0.025 N KOH titrant. Zeta potential vs. pH data were taken by the addition of aliquots of 0.025 N HNO3 titrant. The pH titration was performed using a dynamic program with 15–25 s timesteps and 10–50 uL aliquots per adjustment to control pH with 0.1 pH unit or less variation per datapoint. Three or more repetitions of stock solutions were conducted in which particle materials were dispersed in solution using 10 min mixing in an ultrasonic bath.

Arsenate and iodide sorption

Arsenic sorption reactors were prepared by adding 0.1 g of solid material to 19.9 mL 18.2 Megaohm-cm deionized water and left on a shaker table for 24 h. After overnight equilibration, the reactors were spiked with 0.1 mL 0.01 M sodium arsenate (Sigma Aldrich, 98%); giving a total arsenic concentration of 3.75 ppm. Reactors were then allowed to shake for 24 h, then centrifuged and the supernatant was collected and acidified using optima grade concentrated nitric acid (Fisher 67–70%). Arsenic concentrations were measured using ICP-OES at the 193 nm wavelength against prepared standards.

Batch iodide sorption experiments were prepared by adding 0.1 g of material to 7.425 mL of 18.2 Megaohm-cm deionized water. After 24 h on the shaker table the samples were spiked with 75 µL of 1000 ppm iodide ion chromatography standard (Fluka Analytical), giving the final iodide concentration in each reactor 10 ppm. After another 24 h on the shaker table the samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. The iodide concentration in the supernatant was measured using a Dionex ICS 1100; ion chromatograph, along with reference standards. The solid-liquid partitioning coefficients (KD values (mL/g) were then calculated using Eq. (1)

where Ci is the initial aqueous anion concentration (mg/L), Cf is the final aqueous anion concentration (mg/L), and S is the solid to solution ratio (g/mL)40.

Computational methods

CMD simulations

The CMD simulation methodology follows from our recent study of pure GB, in which each butanediol molecule is dissociatively adsorbed on the surface (i.e., selected surface hydroxyl groups were replaced with singly deprotonated butanediol molecules)28. An 8 × 1 × 6 supercell of boehmite41 was created consisting of two AlOOH layers and two interlayer regions with initial ac dimensions 23.0 Å × 22.3 Å. Each interlayer was expanded to 15 Å, and the number of inserted butanediol molecules varied from 12 diols per interlayer (0.5 diols per unit cell) to 48 diols per interlayer (2.00 diols/u.c.). Next, 20 water molecules and the ions (2 K+ and 2 Cl−, or 1 Ni2+ and 2 Cl−) were randomly inserted into each interlayer. Force field (FF) energy terms involving AlOOH layers and diol molecules were taken from Clayff42,43 and the All-Atom Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS-AA)44, as described previously28. The flexible Simple Point Charge (SPC) water model45 was used, along with ion-water parameters for K+, Ni2+, and Cl−46,47,48. Except for diol-diol interactions, arithmetic mixing rules were used for all Lennard-Jones interactions involving unlike atom pairs. As implemented in OPLS44, geometric mixing rules were used for Lennard-Jones interactions between diol molecules, along with 50% Coulomb subtraction for 1–4 interactions. All CMD simulations were performed at 300 K using three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions with the LAMMPS code49. As described in detail previously28, atomic positions and layer spacings were equilibrated using a series of short constant-volume and constant-pressure simulations, followed by a 2-ns production simulation.

Ab initio molecular dynamic (AIMD) simulations

AIMD simulations were conducted with Mermin’s generalization to finite temperature using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package50,51 (VASP). The exchange-correlation energy was calculated using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), with the parameterization of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof52 (PBE). The projector-augmented wave (PAW) method53was used to describe the interaction between valence electrons and ionic cores, with core electrons together with the nuclei represented by PAW pseudopotentials. The Al(3s,3p), C(2s,2p), Ca(3s,3p,4s), Cl(3s,3p), I(5s,5p), K(4s), Ni(4s,3d) and O(2s,2p) electrons were treated explicitly as valence electrons in the Kohn-Sham (KS) or Mermin-Kohn-Sham (MKS) equations and the remaining core electrons together with the nuclei were represented by PAW pseudopotentials. The plane-wave cutoff energy for the electronic wavefunctions was set to 500 eV, ensuring the total energy of the system to be converged to within 1 meV/atom, with partial occupancies for all bands controlled by Fermi-Dirac smearing.

A 3D-periodic cell approach was used in AIMD simulations at 298 K. Supercells pre-optimized with LAMMPS were used as initial guess structures in AIMD simulations of butanediol-functionalized GB including CaCl2 or KCl in the interlayer space, as well as water molecules; initial structures of Ni-functionalized GB were built by substituting Ni for Ca and I for Cl in supercells containing NiCl2 or NiI2. AIMD simulations were performed at 25 °C in the canonical ensemble (NVT), with fixed number of particles, volume, and temperature. The Monkhorst–Pack special k-point scheme was used for properties averaging in the Brillouin zone. The time step for ion motion was set to 0.7 fs, with velocities scaled at each simulation step to the temperature, and each AIMD simulation was typically run for over 10 ps. A similar computational approach was successfully used in previous study of pristine and functionalized GB28.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files or can be made available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author to request data.

References

Morales, K. H., Ryan, L., Kuo, T. L., Wu, M. M. & Chen, C. J. Risk of internal cancers from arsenic in drinking water. Environ. Health Persp. 108, 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.00108655 (2000).

Bonano, E. Vol. 1 (Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM, (2014).

Rivas, B. L., Urbano, B. F., Sanchez, J., Water-Soluble, Polymers, I. & and Nanoparticles, nanocomposites and hybrids with ability to remove hazardous inorganic pollutants in water. Front. Chem. 6, 320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00320 (2018).

Warner, C. L. et al. High-performance, superparamagnetic, nanoparticle-based heavy metal sorbents for removal of contaminants from natural waters. ChemSusChem 3, 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201000027 (2010).

Ma, J. et al. Removal of radionuclides from aqueous solution by manganese Dioxide-Based nanomaterials and mechanism research: A review. ACS ES&T Eng. 1, 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestengg.0c00268 (2021).

Sellin, P. & Leupin, O. X. The use of clay as an engineered barrier in Radioactive-Waste Management — A review. Clays Clay Min. 61, 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1346/ccmn.2013.0610601 (2024).

Grambow, B. Geological disposal of radioactive waste in clay. Elements 12, 239–245 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.12.4.239

Mills, M. M. et al. Understanding smectite to illite transformation at elevated (> 100°C) temperature: effects of liquid/solid ratio, interlayer cation, solution chemistry and reaction time. Chem. Geol. 615, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2022.121214 (2023).

Tournassat, C. & Appelo, C. A. J. Modelling approaches for anion-exclusion in compacted Na-bentonite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 75, 3698–3710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.001 (2011).

Moore, R. C. et al. Iodine immobilization by materials through sorption and redox-driven processes: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 716, 132820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.166 (2020).

Mariner, P. et al. Advances in Geologic Disposal System Modeling and Application to Crystalline Rock. (SAND2016-9610 R, 2016).

Sevougian, S. et al. Status of progress made toward safety analysis and technical site evaluations for DOE managed HLW and SNF (SAND2016-11232R, 2016).

Neisan, R. S. et al. Arsenic removal by adsorbents from water for small communities’ decentralized systems: Performance, Characterization, and effective parameters. Clean. Technol. 5, 352–402. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol5010019 (2023).

Muhire, C., Tesfay Reda, A., Zhang, D., Xu, X. & Cui, C. An overview on metal Oxide-based materials for iodine capture and storage. Chem. Eng. J. 431 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.133816 (2022).

Vatanpour, V., Madaeni, S. S., Rajabi, L., Zinadini, S. & Derakhshan, A. A. Boehmite nanoparticles as a new nanofiller for Preparation of antifouling mixed matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 401, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2012.01.040 (2012).

Wang, Y., Luo, G., Xu, X. & Xia, J. Preparation of supported skeletal Ni catalyst and its catalytic performance on dicyclopentadiene hydrogenation. Catal. Commun. 53, 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2014.04.011 (2014).

Holm, C. H., Adams, C. R. & Ibers, J. A. The hydrogen bond in boehmite. J. Phys. Chem. 62, 992–994doiDOI. https://doi.org/10.1021/j150566a027 (1958).

Alphonse, P. & Courty, M. Structure and thermal behavior of nanocrystalline boehmite. Thermochim Acta. 425, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2004.06.009 (2005).

Conroy, M. et al. Importance of interlayer H bonding structure to the stability of layered minerals. Sci. Rep. 7, 13274. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13452-7 (2017).

Kosmulski, M. A literature survey of the differences between the reported isoelectric points and their discussion. Colloids Surf. A. 222, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0927-7757(03)00240-1 (2003).

Sugiyama, S., Kanda, Y., Ishizuka, H. & Sotowa, K. Removal and regeneration of aqueous divalent cations by boehmite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 320, 535–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2008.01.037 (2008).

Strathmann, T. J. & Myneni, S. C. Effect of soil fulvic acid on nickel(II) sorption and bonding at the aqueous-boehmite (gamma-AIOOH) interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 4027–4034. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0481629 (2005).

Inoue, M., Kitamura, K., Tanino, H., Nakayama, H. & Inui, T. Alcohothermal treatments of gibbsite - mechanisms for the formation of boehmite. Clays Clay Min. 37, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1346/ccmn.1989.0370109 (1989).

Inoue, M., Kominami, H. & Inui, T. Reaction of aluminium alkoxides with various glycols and the layer structure of their products. J Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans, 3331–3336 (1991).

Inoue, M., Kondo, Y. & Inui, T. An Ethylene-Glycol derivative of boehmite. Inorg. Chem. 27, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1021/Ic00275a001 (1988).

Bell, N. S. et al. Polymer intercalation synthesis of glycoboehmite nanosheets. Appl. Clay Sci. 214 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2021.106273 (2021).

Inoue, M., Kominami, H., Kondo, Y. & Inui, T. Organic derivatives of layered inorganics having the second stage structure. Chem. Mat. 9, 1614–1619. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm970018h (1997).

Greathouse, J. A., Weck, P. F., Bell, N. S., Kruichak, J. N. & Matteo, E. N. Structural and spectroscopic properties of Butanediol-Modified boehmite materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 3533–3542. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.3c07838 (2024).

Inoue, M. Glycothermal synthesis of metal oxides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 16, S1291–S1303. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/16/14/042 (2004).

Siahpoosh, S. M., Salahi, E., Hessari, F. A. & Mobasherpour, I. Synthesis of γ-Alumina nanoparticles with High-Surface-Area via Sol-Gel method and their performance for the removal of nickel from aqueous solution. Bull. Soc. R Sci. Liege. 812–934. https://doi.org/10.25518/0037-9565.5748 (2016).

Hiemstra, T., Yong, H. & Van Riemsdijk, W. H. Interfacial charging phenomena of aluminum (hydr)oxides. Langmuir 15, 5942–5955 (1999).

Jolivet, J. P. et al. Size tailoring of oxide nanoparticles by precipitation in aqueous Medium. A Semi-Quantitative modelling. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 3281–3288. https://doi.org/10.1039/b407086k (2004).

Islam, M. A., Angove, M. J. & Morton, D. W. Macroscopic and modeling evidence for nickel(II) adsorption onto selected manganese oxides and boehmite. J. Water Proc. Eng. 32, 100964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100964 (2019).

Chabi, D., Seidou, T. W., Espoire, M. M. R. B., Dai, Y. & Zuo, Y. A Review of the Distribution Coefficient (Kd) of Some Selected Heavy Metals over the Last Decade (2012–2021). GEP 10, 199–242, (2022). https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2022.108014

Miller, A. W. & Wang, Y. F. Radionuclide interaction with clays in dilute and heavily compacted systems: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1981–1994. https://doi.org/10.1021/es203025q (2012).

Choung, S., Kim, M., Yang, J. S., Kim, M. G. & Um, W. Effects of radiation and temperature on iodide sorption by Surfactant-Modified bentonite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9684–9691. https://doi.org/10.1021/es501661z (2014).

Liang, L. & Li, L. Adsorption behavior of calcined layered double hydroxides towards removal of iodide contaminants. J. Radioanal Nucl. Chem. 273, 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-007-0740-x (2007).

Miyata, S. Anion-Exchange properties of Hydrotalcite-Like compounds. Clays Clay Min. 31, 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1346/ccmn.1983.0310409 (1983).

Iglesias, L. et al. A comprehensive study on iodine uptake by selected LDH phases via coprecipitation, anionic exchange and reconstruction. J. Radioanal Nucl. Chem. 307, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4285-0 (2016).

Miller, A. W., Kruichak, J. N., Mills, M. M. & Wang, Y. Iodide uptake by negatively charged clay interlayers? J. Environ. Radioact. 147, 108–114 (2015).

Hill, R. J. Hydrogen atoms in boehmite: A single crystal X-Ray diffraction and molecular orbital study. Clays Clay Min. 29, 435–445. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.1981.0290604 (1981).

Cygan, R. T., Liang, J. J. & Kalinichev, A. G. Molecular models of Hydroxide, Oxyhydroxide, and clay phases and the development of a general force field. J. Phys. Chem. B. 108, 1255–1266. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0363287 (2004).

Pouvreau, M., Greathouse, J. A., Cygan, R. T. & Kalinichev, A. G. Structure of hydrated gibbsite and brucite edge surfaces: DFT results and further development of the clayff classical force field with Metal–O–H angle bending terms. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 14757–14771. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b05362 (2017).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja9621760 (1996).

Teleman, O., Jonsson, B. & Engstrom, S. A. Molecular dynamics simulation of a water model with intramolecular degrees of freedom. Mol. Phys. 60, 193–203 (1987).

Koneshan, S., Rasaiah, J. C., Lynden-Bell, R. M. & Lee, S. H. Solvent Structure, Dynamics, and ion mobility in aqueous solutions at 25 degrees C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 4193–4204. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp980642x (1998).

Babu, C. S. & Lim, C. Empirical force fields for biologically active divalent metal cations in water. J. Phys. Chem. A. 110, 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp054177x (2006).

Smith, D. R. & Dang, L. X. Computer simulations of NaCl association in polarizable water. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 3757–3766. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.466363 (1994).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comp. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2021.108171 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169–11186. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Abinitio Molecular-Dynamics for Liquid-Metals. Phys. Rev. B. 47, 558–561. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Molecules, Solids, and Surfaces- applications of generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B. 48, 4978–4978. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.48.4978.2 (1993). Atome.

Choung, S., Um, W., Kim, M. & Kim, M. G. Uptake mechanism for iodine species to black carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 10349–10355. https://doi.org/10.1021/es401570a (2013).

Xu, C. et al. Molecular environment of stable iodine and radioiodine (129I) in natural organic matter: evidence inferred from NMR and binding experiments at environmentally relevant concentrations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 97, 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.08.030 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Nuclear Energy, through the Office of Spent Fuel and Waste Science and Technology (SFWST) Research and Development Campaign. Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-mission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC (NTESS), a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (DOE/NNSA) under contract DE-NA0003525. This work is authored and owned by an employee of NTESS and is responsible for its contents. Any subjective views or opinions expressed in the written work do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Government. The publisher acknowledges the U.S. Government license to provide public access under the DOE Public Access Plan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S.B. synthesized the GB material and J.N.K modified the material with divalent cations. J.N.K carried out the arsenate and iodide sorption studies. N.S.B., J.N.K, M.A.R, S.G.R, B.J., M.N.L, collected and analyzed the data for the various material characterization techniques. J.A.G, and P.F.W performed classical and *ab initio* molecular dynamics simulations of GB. J.N.K, N.B., J.A.G, Y.W, P.F.W, and E.N.M were involved with writing the manuscript and discussing results and providing comments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kruichak, J.N., Bell, N.S., Greathouse, J.A. et al. Novel nickel-functionalized glycoboehmite materials for iodide and arsenate capture. Sci Rep 15, 39761 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23429-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23429-6