Abstract

This work utilized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) capped with both tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) and quaternized tetraethylenepentamine (Q-TEPA) as stabilizer and selective recognition element for Hg2+ over competing metal ions (Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, La3+). The performance of Q-TEPA-AgNPs was compared to TEPA-AgNPs, demonstrating significantly higher selectivity for Hg2+ detection. The effect of Q-TEPA concentration (1 mM, 2 mM, and 4 mM) during the preparation of Q-TEPA-AgNPs on Hg2+ selectivity, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) was investigated. LOD and LOQ values of Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs were ~ 10 µM and ~ 31 µM, respectively. However, the linear detection range was wider for Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs (spanning 20–150 µM) compared to Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs (20–100 µM). LOD and LOQ of Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs increased to ~ 20 µM and ~ 60 µM, respectively, with linear range between 20 and 100 µM. Higher concentration of Q-TEPA enhanced Hg2+ selectivity but adversely increased LOD and LOQ, and narrowed the linear detection range. The response is rapid: after Hg2+ addition the plasmon band disappears within ≤ 12 s, enabling near-real-time visual readout. The nanosensor enabled highly selective Hg2+ sensing and functions effectively under real-world conditions, with performance remaining consistent when tested using Hg2+ spiked into tap water, confirming robustness against matrix interferences. This optimized Q-TEPA-AgNPs nanosensor offers a promising, selective, and practical approach for mercury detection in complex aqueous environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mercury (Hg) is a toxic heavy metal that is harmful to both the environment and humans. Due to increasing human activity, mercury pollution has emerged as a serious global problem, and its prevalence continues to rise1. Recent studies suggest that even low concentrations of mercury can have significant ecological and physiological impacts, underscoring the need for early detection and robust regulatory measures2. Mercury continuously enters ecosystems through mining, industrial emissions, atmospheric deposition, and improper waste disposal3. In industrial and environmental contexts with higher Hg2+ concentrations, such as mining effluents or chlor-alkali wastewater, levels typically ranged between 5 and 500 µM4. In aquatic systems, microorganisms convert mercury into methylmercury, a highly toxic compound that bioaccumulates through marine food webs, ultimately reaching humans via consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish5.

It adversely affects reproductive success and disrupts ecological distribution and balance6,7. Mercury exposure also impairs neurological functions in diverse species. Empirical studies demonstrate that mercury-induced behavioral alterations can reduce reproductive success and cause population-level mortality8. Considering marine ecosystems, mercury pollution disrupts their biodiversity and ecological balance7,8,9. Mercury pollution poses significant threats to human health, particularly neurological and developmental impairments10. Chronic exposure is associated with cognitive deficits, cardiovascular disorders, and immune system dysfunction11,12. It can cause cognitive impairment, lack of attention, and learning difficulties in fetuses and children13,14.

Dietary consumption of contaminated seafood represents a primary route of human mercury exposure15, as well as activities like metal mining (especially gold and silver), coal burning, and industrial waste disposal16. Despite international regulatory frameworks like the Minamata Convention, mercury pollution continues to present significant challenges requiring sustained mitigation efforts17. To enable rapid response to mercury pollution, mitigate environmental damage, and reduce associated health risks, it is critical to establish baseline contamination levels. However, conventional analytical techniques such as atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) present limitations due to their high cost, operational complexity, and extensive sample preparation requirements. This underscores the need for developing simpler, faster, and more accessible methods for mercury (Hg) detection and quantification18. Nanosensors have been used due to their low cost and ease of use compared to traditional detection methods.

Nanosensors are capable of quickly and accurately detecting small quantities of target substances, even at very low concentrations that may reach fractions of a trillion19,20,21. Nanosensors based silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exploit the property of localized surface plasmons, which are collective electron oscillations in metallic nanoparticles resulting from the interaction between light and their surfaces22,23. Many published studies have reported on the use of nanosensors based AgNPs for the detection and quantification of mercury ions. Cao et al. reported the synthesis of AgNPs with sizes ranging from 16 to 22 nm and modified with the natural compound “lignosulfonate”. Such nanosensor was used to detect mercury with a detection range of 0–68 µM24. Samuel et al. reported a novel colorimetric method with a LOD of 1 nM of mercury ions using polyallylamine (PAH)-capped silver nanoparticles25. Pandey et al.26 developed a colorimetric selective Hg2+ sensor using polyvinyl pyrrolidone-capped silver nanoparticles and O-phenylenediamine with LOD of 3.29 µM. A simple colorimetric nanosensor based on the surface’s modification of AgNPs with the Schiff base of 2-aminobenzohydrazide with triazole substituted vanillin27. The LOD of mercury was 0.04 µM. Yılmaz et al.28 developed a colorimetric detection method using chlorophyll functionalized AgNPs with LOD of 2.7 µM. The synthesis of calixarene-functionalized silver nanoparticles that exhibit selective colorimetric detection of mercury ions with a detection limit of 0.5 nmol was reported by Vyas et al.29.

Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) is a polyamine compound used in various applications due to its chelating and crosslinking properties30. Dong and co-workers demonstrated a high-performance CO2 sorbent by immobilizing 75 wt% TEPA on KOH-modified CNTs, exhibiting enhanced in surface area, and cost-effective regeneration, making it promising for industrial CO2 capture from flue gas 31. Zhou et al. reported the synthesis of CO2 capture material made of SBA-15@MIL-101(Cr) composite modified with TEPA, enhancing thermal stability, and superior CO2 uptake (298K, 100 kPa) with low-energy regeneration and reusability32. TEPA-functionalized ATA@AC composite via one-pot synthesis was fabricated as adsorbent, achieving 432.8 mg/g capacity Pb(II) removal through combined physisorption/chemisorption, with excellent reusability33.

In this study, tetraethylenepentamine was first quaternized using iodomethane to produce Q-TEPA. AgNPs were then synthesized via the chemical reduction method and then stabilized separately using TEPA and Q-TEPA. The fabricated nanosensors were tested for sensitive and selective detection of Hg2+ against Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pd2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, and La3+ ions, see Fig. 1. The LOD and LOQ of the nanosensors were determined. The Q-TEPA and fabricated nanosystems were characterized using FT-IR, NMR, TEM, EDX, DLS and UV–vis.

Experimental methods

Materials

Sodium borohydride (NaBH4, ≥ 99%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Silver nitrate (AgNO3, ≥ 98.0%) was obtained from Riedel-de Haën (Paris, France). Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA, ≥ 99%) and iodomethane (CH3I, ≥ 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aluminum(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O, 99%), lead(II) nitrate (Pb(NO3)2, ≥ 99%), copper(II) nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, ≥ 99.9%), chromium(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Cr(NO3)3·9H2O, ≥ 99.9%), cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate (Cd(NO3)2·4H2O, ≥ 98%), zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, ≥ 98%), and tetrahydrofuran (C4H₈O, 99%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).Ferric chloride anhydrous (FeCl3, 96%) was sourced from Qualikems (Vadodara, India). Ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O, ≥ 99%) was obtained from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India). Manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2·4H2O, ≥ 99%) was purchased from CDH (New Delhi, India). Cobalt(II) acetate tetrahydrate ((CH3COO)2Co·4H2O, 98%) and nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 98%) were acquired from BDH (Poole, UK). Lanthanum chloride heptahydrate (LaCl3·7H2O, ≥ 98%) was obtained from BDH (Poole, UK). Sodium arsenate heptahydrate (Na2HAsO4·7H2O, ≥ 97%) was purchased from Koch-light Laboratories Ltd (Colnbrook, England). Mercury(II) chloride (HgCl2, ≥ 99%) was acquired from Avonchem (Macclesfield, England).

Instruments

UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a U-2910 Hitachi spectrophotometer (Japan). Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed on L1600300 PerkinElmer FT-IR spectrometer (UK) over the range of 400–4000 cm−1. Zeta potential and hydrodynamic size measurements were conducted using a ZEN3600 Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS series (UK). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging was carried out on a JEM-1011 JEOL microscope. Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) was performed using a JEOL JSM-6380 LA scanning electron microscope. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were acquired using a JNM-ECA600II spectrometer (Japan). ICP-MS analysis was performed using a PerkinElmer NexION 300 spectrometer.

Synthesis of Q-TEPA

The Menshutkin reaction was used to synthesize Q-TEPA34. First, 2 ml of TEPA was dissolved in 200 ml Tetrahydrofuran (THF) in a separatory funnel. Additionally, 9 ml of iodomethane was dissolved in 200 ml of THF in a round bottom flask and cooled in an ice bath. The TEPA solution was added dropwise onto the Iodomethane solution. A light-yellow precipitate was formed. The solid was filtered and washed several times with THF solvent and dried under vacuum. Finally, the collected product was characterized using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and, 1H and 23C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Synthesis of TEPA-AgNPs and Q-TEPA-AgNPs

Prior to synthesis, all glassware was rigorously cleaned with aqua regia (3:1 HCl:HNO3) and rinsed with deionized water to minimize contamination. According to the following description in given literature35, with minor adjustments, AgNPs were synthesized via chemical reduction using NaBH4. A 1 mM solution of silver nitrate (AgNO3) was made in deionized water to a final volume of 100 mL and transferred to a 250 mL round bottom flask. The solution was stirred at 800 rpm at room temperature. While stirring, 1 mg of NaBH4 was added to the solution. After a minute, a characteristic pale-yellow color appeared. Subsequently, 2 mL of a freshly prepared 1 mM (or 2 mM) TEPA mixture was introduced into the AgNPs solution at a speed of 800 rpm and room temperature. The stirring continues in the dark for 1 h. Over this period, the color changed from pale yellow to light brown. The resulting materials were referred to as TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs.

Similar synthesis protocol was performed for the preparation of Q-TEPA-stabilized AgNPs. Freshly prepared AgNPs dispersions were treated with three Q-TEPA concentrations (1, 2, or 4 mM) at 800 rpm and room temperature. The resulting materials were referred to as Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs. Notably, the 1 mM and 2 mM Q-TEPA solution yielded a deep green color, while higher concentrations of 4 mM produced yellow hues.

Colorimetric detection of Hg2+ ions

Briefly, the sensing experiments was conducted by adding 1 mL of selected heavy metal ion solutions (Hg2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pd2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, and La3+) to 2 mL aliquots of TEPA-AgNPs or Q-TEPA-AgNPs solutions. The heavy metal solutions were prepared as 1 mM solutions in deionized water with pH adjusted to 4.5. Color changes were then monitored, and the LSPR response was analyzed using UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy for the solutions.

Colorimetric detection of Hg2+ among heavy metals using real tap water

Two multicomponent solutions were prepared in tap water for selectivity assessment. Each solution contained the following heavy metal ions at 1 mM concentration: Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, and La3+. The first solution served as a mercury-free control, while the second solution was supplemented with Hg2+ (1 mM). These heavy metal ion solutions (1 mL each) were introduced into 2 mL aliquots of a Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs solution. The resulting mixtures were then analyzed using UV–Vis spectrometry.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of Q-TEPA

The success of the quaternization process for TEPA was confirmed through the 1H NMR spectra. Peaks were found around ~ 2.2 ppm which corresponding to methylene protons adjacent to free amine groups (–CH2–NH2), have completely disappeared in the spectrum of Q-TEPA. A new peak appears in the Q-TEPA spectrum at 1.4 ppm, related to methyl protons on the quaternized nitrogen (Fig. 1S A). Moreover, the 13C NMR spectral data confirm the quaternization of TEPA, as evidenced by two diagnostic peaks in the Q-TEPA spectrum (Fig. 1S B), a resonance at 49 ppm assigned to N+–CH3 carbons and a second peak at 61 ppm characteristic of N+–CH2 groups.

The success of the quaternization process was further confirmed by IR spectroscopy. Bands at 3293 cm−1 and 3357 cm−1, present in the TEPA spectrum and assigned to N–H stretching vibrations of primary/secondary amines, disappeared in the Q-TEPA spectrum. Concurrently, a new band appeared at 3011 cm−1 in the Q-TEPA spectrum, indicating C–H stretching vibrations of the saturated N+CH2–H group (Fig. 1S C).

Fabrication of AgNPs capped with TEPA and Q-TEPA

Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) was employed as a reducing agent for Ag+ ions in aqueous solutions36,37. Q-TEPA and TEPA served as capping agents to stabilize AgNPs against aggregation. Their efficacy in enabling Hg2+ detection was systematically compared through colorimetric sensing assays.

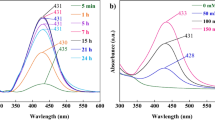

Absorption spectra of Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs solutions showed characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) maxima at 393 nm, 394 nm, and 399 nm, respectively. In contrast, TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs solutions (exhibited SPR maxima at 390 nm for both concentrations (Fig. 2A). Based on spectral studies38,39, the estimated size range for both Q-TEPA-AgNPs and TEPA-AgNPs was 10–20 nm. This partially aligns with TEM results, which revealed spherical particles ranging from 15 to 35 nm with an average diameter of 21.53 nm (Fig. 2B).

To confirm the elemental composition, EDX analysis was performed on two samples: Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs (Fig. 2C) and TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs (Fig. 2D). The elemental analysis demonstrated silver (Ag), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and iodine (I) in both samples (Table 1). The analysis revealed substantially higher atomic percentages of carbon (19.04 at%), nitrogen (24.59 at%), and iodine (9.29 at%) in Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs compared to TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs (17.73 at% C, 11.36 at% N, and 0.08 at% I).The trace iodine in TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs was negligible and likely reflected residual impurities or an instrumental artifact.

Dynamic light scattering technique (DLS) was used to determine hydrodynamic size (Fig. 2S) and surface zeta potential of Q-TEPA-AgNPs and TEPA-AgNPs. Zeta potential measurements were conducted across varying pH conditions for Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs. As shown in Fig. 3, Q-TEPA-AgNPs exhibited pH-independent zeta potential values in acidic, neutral, and basic media at both stabilizer concentrations. This stability arises from the permanent positive charge of quaternized Q-TEPA, which prevents protonation-driven charge fluctuations. In contrast, TEPA-AgNPs displayed pH-dependent zeta potentials, reflecting electrical instability. This behavior is consistent with the protonation of TEPA’s amine groups in acidic media and deprotonation under basic conditions.

Colorimetric detection of Hg2+ ion

In this study, the feasibility of Hg2+ ions detection using Q-TEPA-AgNPs and TEPA-AgNPs was investigated. The detection mechanism relies on a spontaneous redox reaction between AgNPs and Hg2+ ions, driven by the difference in electrochemical potentials. The standard reduction potential of Ag+/Ag (0.80 V vs Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE)) is lower than that of Hg2+/Hg (0.85 V vs SHE), enabling Hg2+ to oxidize Ag0 while being reduced to Hg0 40,41,42,43. The resulting mercury-silver amalgam (Ag–Hg) forms on the AgNPs surface, altering its properties and enabling detection (Scheme 1). The synthesized solutions of Q-TEPA-AgNPs exhibited different colors depending on the stabilizer concentration: dark green for 1 mM and 2 mM Q-TEPA, and yellow for 4 mM Q-TEPA. In contrast, TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs appeared pale brown. Upon interaction with Hg2+ ions, an amalgam layer (Ag–Hg) forms on the nanoparticle surfaces, quenching their SPR. This leads to a blue shift in the SPR peak and ultimately results in colorless solutions due to the loss of plasmonic activity42,44. In a timed mixing experiment performed directly in the cuvette (2.0 mL Q-TEPA (1 mM)–AgNPs + 1.0 mL of a 1.0 mM Hg2+ solution; acquisition initiated immediately), the plasmon band was not detected in the first recorded spectrum at 12 s, indicating a response time ≤ 12 s under these conditions (Fig. 3S).

The selectivity of TEPA-AgNPs and Q-TEPA-AgNPs for Hg2+ detection against competing metal ions (Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pd2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, La3+) was evaluated by UV–Vis spectroscopy. TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs demonstrated low selectivity: Hg2+ induced characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) quenching due to amalgam formation, while Mn2+ and La3+ generated a new red-shifted peak near the SPR region, indicating strong chemical interactions. Other ions caused SPR intensity reduction via nanoparticle agglomeration (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast, Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs exhibited high Hg2+ selectivity and Hg2+ completely quenched the SPR peak, confirming effective amalgamation (Fig. 4C–E). For As5+ at Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, a new peak formed alongside SPR intensity loss, indicating side reactions and aggregation (Fig. 4C, D). Notably, Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs exhibited no spectral response to interfering ions, demonstrating exceptional selectivity for Hg2+ (Fig. 4E). For Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, moderate selectivity was observed for Fe2+ and As5+ ions. In contrast, Zn2+, Fe3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, and Mn2+ showed consistently low interference at Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs. Co2+, Al3+, and La3+ exhibited even lower interference at these nanosensors. However, selectivity toward Co2+, Al3+, and La3+ decreased significantly at Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs compared to Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs. For Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs, interference from most metals remained comparable to levels observed at Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, while Co2+, As5+, Al3+, and La3+ showed substantially reduced the interference (Fig. 4F).

UV–Vis absorption spectra of 1 mM solutions of various metal ions (Hg2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pd2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, and La3+) incubated with: (A) TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, (B) TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs,(C) Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, (D) Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, and (E) Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs, (F) Relative change in the absorbance of Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs in the presence of Hg2+ and selected metal ions. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 3 min and at pH 4.8.

The selectivity of Q-TEPA toward Hg2+ from its ability to exclude competing metal ions and allowing Hg2+ to penetrate the organic layer and reach the silver surface. This triggers a redox reaction (Ag0 + Hg2+ → Ag+ + Hg0), forming a silver–mercury amalgam (Ag–Hg). EDX analysis provided preliminary support for the proposed mechanism. At 250 μM Hg2+, distinct Hg peaks (~ 2.2 keV and ~ 10 keV) appear alongside Ag peaks, with quantified contents of 12.6 wt% Hg and 40.6 wt% Ag (Fig. 4S(A) and Table 1S), confirming co-localization and amalgam formation via galvanic replacement. While Q-TEPA elements (C, N, I) persist, the iodine content (4.1 wt%) is lower than in unreacted Q-TEPA-coated AgNPs. At 80 μM Hg2+, the same peaks are observed with a reduction in Hg2+ concentration (1.3 wt%), consistent Ag (40.8 wt%), and higher concentration of I (6.3 wt%), shown in Fig. 4S(B) and Table 1S.

For further mechanistic interpretation, EDX elemental mapping was employed to validate the proposed mechanism. In the sample exposed to 250 μM Hg2+, the Ag map revealed a uniform distribution in the nanoparticle, while the Hg map showed strong spatial correlation with Ag-rich regions, directly confirming amalgam formation, Fig. 5S(A). Consistent with point analysis results, the I and N maps verified the persistence of the Q-TEPA shell, though reduced iodine intensity (compared to unreacted particles) visually supported partial displacement by Hg2+. In contrast, the 80 μM Hg2+ sample exhibited similar Ag distribution patterns with significantly attenuated Hg signals, consistent with the lower mercury content (1.3 wt%) measured in point analysis, Fig. 5S(B). I and N maps at this lower concentration spatially corroborated the higher iodine retention (6.3 wt%).

The proposed detection mechanism, which undergoes a redox reaction, is substantiated by a morphological study. TEM characterization reveals that Q-TEPA (1 mM)-AgNPs exhibit almost spherical morphology prior to Hg2+ exposure with average size of 21.6 ± 4.8 nm (Fig. 2B). Following treatment with 250 μM Hg2+, the nanoparticles maintain comparable dimensions with average size of 19.3 ± 6.5 nm, shown in Fig. 6S. These morphological transformations provide direct evidence of amalgam formation through surface redox processes (Ag0 + Hg2+ → Ag+ + Hg0), without significant change in particle size.

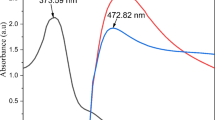

Systematic UV–Vis spectroscopic measurements across the full Hg2+ concentration range demonstrate progressive attenuation of the plasmon resonance peak with increasing Hg2+ concentration (Fig. 7S). This concentration-dependent plasmon damping, characteristic of surface amalgamation, establishes the foundation for quantitative detection as evidenced by the linear calibration curve derived from Fig. 7S. A calibration curve was drawn to determine the linear relationship between Hg2+ concentration and the change in absorbance (ΔA) for Q-TEPA (1 mM)-AgNPs, Q-TEPA (2 mM)-AgNPs, and Q-TEPA (4 mM)-AgNPs, and to determine the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ). Here, ΔA is defined as ΔA = A0 − A, Where A0 is the absorbance of the AgNPs dispersion before Hg2+ addition and A is the absorbance after Hg2+ addition, evaluated at the plasmon-band maximum. The LOD and LOQ were calculated using the two Eqs. (3.3 × σ)/S and (10 × σ)/S, respectively. Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs exhibited a linear response (R2 = 0.969) to Hg2+ concentrations between 20 and 150 μM, with a LOD of 10.68 μM and LOQ of 32.9 μM (Fig. 5A). For Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs, the results showed a linear relationship between the concentration of 20 µM and 100 µM Hg2+ (R2 = 0.956), with the LOD equal to 10.47 µM and the LOQ equal to 31.7 µM (Fig. 5B). Quantitative analysis of Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs revealed a linear response (R2 = 0.974) to Hg2+ concentrations from 20 to100 μM. The method achieved a LOD of 20.26 μM and LOQ of 61.4 μM (Fig. 5C). It is clear that a significant increase in the Q-TEPA concentration increases the LOD and LOQ and narrows the linear range. This is likely due to the increased stabilizer concentration isolating the AgNPs from the Hg2+, thus inhibiting the oxidation–reduction reaction between the AgNPs and the Hg2+.

Several AgNP-based colorimetric sensors reported in the literature achieve lower LODs (nM–low µM), whereas the present Q-TEPA–AgNP platform delivers LODs of ~ 10 µM (1–2 mM Q-TEPA) and ~ 20 µM (4 mM Q-TEPA). While the fabricated LOD is higher, the system is intentionally tuned for rapid screening in matrices where Hg2+ commonly occurs at tens to hundreds of micromolar—such as mining effluents and chlor-alkali wastewaters—rather than for ultra-trace monitoring in drinking water. Under these more challenging, high-ionic-strength conditions, Q-TEPA–AgNPs retain selectivity toward Hg2+ without masking agents, give a visible response within ≤ 12 s, and require only simple mixing and routine UV–Vis (or naked-eye) readout. The stabilizer is inexpensive, and the synthesis is straightforward, supporting low cost, operational simplicity, and field-friendly deployment for on-site triage of industrial/complex aqueous samples.

Colorimetric detection of Hg2+ among heavy metals using tap water

Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs were selected as the nanosensor for Hg2+ detection in tap water under real-world conditions, including in the presence of competing metal ions with or without Hg2+. Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs was chosen because it uses a lower Q-TEPA concentration compared to Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs, as well as having a LOD for Hg2+ around 10 µM. Furthermore, it exhibits a longer linear range (20–150 µM Hg2+) compared to the 20–100 µM ranges observed for Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs.

Two competing metal ion solutions (Hg2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, As5+, Co2+, Al3+, La3+) were prepared at 1 mM in tap water sourced from the King Saud University campus network, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Two multicomponent solutions were prepared to evaluate nanosensor selectivity: (1) a control containing all ions except Hg2+, and (2) a test solution containing the same ions with Hg2+. The nanosensor exhibited exceptional Hg2+ selectivity, as evidenced by complete quenching of the SPR peak only in Hg2+-containing solutions (Fig. 6A).

(A) Comparative UV–Vis absorption spectra of Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs after addition of solutions containing all competing metal ions (1 mM) prepared in tap water with and without Hg2+. (B) Comparative UV–Vis absorption spectra of Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs after addition of Hg2+ (50 µM and 1 mM) prepared in tap water. (C) Calibration curve (ΔAbs vs Hg2+ concentration) for Hg2+ detection using Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs including 50 µM Hg2+ solution prepared in tap water. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 3 min and at pH 5.7.

To validate the consistency between tap water and standard deionized water measurements, we initially analyzed a 50 µM Hg2+ solution prepared in tap water. UV–Vis spectroscopy revealed a characteristic decrease in SPR peak intensity (Fig. 6B). This concentration-dependent response confirmed the nanosensor’s sensitivity. Notably, when plotted against the calibration curve, the 50 µM tap water measurement aligned precisely with the established linear relationship (Fig. 6C), demonstrating reliable performance in complex matrices.

For comprehensive validation under realistic conditions, four tap water samples collected from the King Saud University water network were spiked with Hg2+ at concentrations of 45, 50, 60, and 70 µM. These undiluted samples were analyzed colorimetrically using Q-TEPA–AgNPs, with concentrations determined via the UV–Vis calibration curve (Fig. 5A). Method validation was performed through parallel ICP–MS analysis. As detailed in Table 2S, the colorimetric method yielded concentrations of 49.37, 39.78, 63.41, and 73.25 µM, corresponding to recoveries (R%) of 98.74%, 88.42%, 105.68%, and 104.64%, respectively. ICP–MS measurements gave values of 47.24, 39.79, 58.64, and 75.30 µM, with recoveries of 94.48%, 93.22%, 97.73%, and 107.57%, respectively. The strong correlation between methods observed across all tested concentrations, despite differences in sample preparation protocols, conclusively validates the nanosensor’s accuracy for tap water analysis from the King Saud University water network. To further strengthen the validation, the detection approach was extended to two additional tap water sources distinct from the King Saud University supply (As Suwaidi district and Al-Muzahmiyya town). These samples were also spiked with Hg2+ at 45 µM and 70 µM and analyzed using both the colorimetric method and ICP–MS. As summarized in Table 3S, the calculated recoveries for the colorimetric method ranged from ~ 85% to 110%, while ICP–MS recoveries ranged from ~ 92% to 103%. These results demonstrate consistent performance across multiple independent water sources, confirming that the nanosensor provides accurate and reproducible Hg2+ detection in diverse real-water matrices.

Conclusions

In this work, a selective Hg2+ nanosensor based on AgNPs was developed using Q-TEPA as a stabilizer. The effect of varying the Q-TEPA stabilizer concentration on selectivity, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) was studied. It was found that significantly increasing the stabilizer concentration enhances selectivity towards Hg2+ but simultaneously increases the LOD and LOQ and narrows the linear detection range. This high selectivity stems from the strong affinity of Q-TEPA-capped silver for Hg2+, facilitating selective amalgamation even amidst competing ions. Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs were selected as the optimal nanosensor owing to their lowest LOD and the broadest linear detection range compared to Q-TEPA(2 mM)-AgNPs and Q-TEPA(4 mM)-AgNPs. Specifically, Q-TEPA(1 mM)-AgNPs achieved an LOD of ~ 10 µM and a linear range spanning 20–150 µM Hg2+. The nanosensor has been experimentally proven to enable highly selective Hg2+ sensing and functions effectively under real-world conditions. Crucially, nanosensor performance remained consistent when tested using Hg2+ spiked into actual tap water, confirming robustness against common matrix interferences. This optimized Q-TEPA-AgNP nanosensor offers a promising, selective, and practical approach for mercury detection in complex aqueous environments like tap water. It is clarified here that while the nanosensor demonstrates robustness in complex matrices, its current LOD (~ 10 µM, 2.0 mg/L) exceeds regulatory limits for drinking water, this nanosensor may be applied for rapid screening applications in higher-concentration industrial and environmental contexts.

Data availability

All data obtained from this study are included in this article.

References

Wu, Y.-S. et al. The toxicity of mercury and its chemical compounds: Molecular mechanisms and environmental and human health implications: A comprehensive review. ACS Omega 9(5), 5100–5126 (2024).

Brocza, F. M., Rafaj, P., Sander, R., Wagner, F. & Jones, J. M. Global scenarios of anthropogenic mercury emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24(12), 7385–7404 (2024).

Budnik, L. T. & Casteleyn, L. Mercury pollution in modern times and its socio-medical consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 654, 720–734 (2019).

Yokoo, E. M. et al. Low level methylmercury exposure affects neuropsychological function in adults. Environ. Health 2(1), 8 (2003).

Crespo-Lopez, M. E. et al. Environmental pollution challenges public health surveillance: The case of mercury exposure and intoxication in Brazil. Lancet Regional Health-Americas 39, 100880 (2024).

Xu, F., Wang, Y., Fang, J. & Zhu, Z. Menopause-dependent correlations of blood mercury levels with bone mineral density and appendicular lean mass index in middle-aged women. Front. Public Health 12, 1501162 (2025).

Gerson, J. R. et al. Amazon forests capture high levels of atmospheric mercury pollution from artisanal gold mining. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 559 (2022).

Mao, L. et al. Comprehensive insight into mercury contamination in atmospheric, terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems surrounding a typical antimony-coal mining district. J. Hazard. Mater. 469, 133880 (2024).

Tao, Z., Dai, S. & Chai, X. Mercury emission to the atmosphere from municipal solid waste landfills: A brief review. Atmos. Environ. 170, 303–311 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Soerensen, A. L., Schartup, A. T. & Sunderland, E. M. A global model for methylmercury formation and uptake at the base of marine food webs. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34(2), e2019GB006348 (2020).

Driscoll, C. T., Mason, R. P., Chan, H. M., Jacob, D. J. & Pirrone, N. Mercury as a global pollutant: Sources, pathways, and effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47(10), 4967–4983 (2013).

Jeong, H., Ali, W., Zinck, P., Souissi, S. & Lee, J.-S. Toxicity of methylmercury in aquatic organisms and interaction with environmental factors and coexisting pollutants: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 943, 173574 (2024).

Charkiewicz, A. E., Omeljaniuk, W. J., Garley, M. & Nikliński, J. Mercury exposure and health effects: What do we really know?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26(5), 2326 (2025).

Mills, W. F. et al. Mercury exposure in an endangered seabird: Long-term changes and relationships with trophic ecology and breeding success. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020(287), 20202683 (1941).

Al-Sulaiti, M. M., Al-Ghouti, M. A., Ramadan, G. A. & Soubra, L. Health risk assessment of methyl mercury from fish consumption in a sample of adult Qatari residents. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195(5), 617 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Improved anthropogenic mercury emission inventories for China from 1980 to 2020: Toward more accurate effectiveness evaluation for the Minamata convention. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57(23), 8660–8670 (2023).

Evers, D. C., Keane, S. E., Basu, N. & Buck, D. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Minamata Convention on Mercury: Principles and recommendations for next steps. Sci. Total Environ. 569, 888–903 (2016).

Planeta, K. et al. The assessment of the usability of selected instrumental techniques for the elemental analysis of biomedical samples. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3704 (2021).

Ivanišević, I. The role of silver nanoparticles in electrochemical sensors for aquatic environmental analysis. Sensors 23(7), 3692 (2023).

Kant, K. et al. Roadmap for plasmonic nanoparticle sensors: Current progress, challenges and future prospects. Nanoscale Horizons (2024).

Alberti, G., Zanoni, C., Magnaghi, L. R. & Biesuz, R. Gold and silver nanoparticle-based colorimetric sensors: New trends and applications. Chemosensors 9(11), 305 (2021).

Gao, B. et al. Light management on silicon utilizing localized surface plasmon resonance of electroless plated silver nanoparticles. Opt. Mater. Express 9(9), 3753–3764 (2019).

Alzoubi, F., Ahmad, A. A., Aljarrah, I. A., Migdadi, A. & Al-Bataineh, Q. M. Localize surface plasmon resonance of silver nanoparticles using Mie theory. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 34(32), 2128 (2023).

Cao, X. et al. Visual and colorimetric determination of mercury (II) based on lignosulfonate-capped silver nanoparticles. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 16(1), 2169590 (2023).

Samuel, V. R. & Rao, K. J. A colorimetric sensor for the stable and selective detection of mercury ions using PAH-capped silver nanoparticles in an aqueous medium. Appl. Nanosci. 14(1), 33–42 (2024).

Pandey, S., Gupta, S. M. & Sharma, S. K. Detection of mercury in aqueous system via O-Phenylenediamine using polyvinyl pyrrolidone functionalized silver nanoparticles. Microchem. J. 207, 112094 (2024).

Ali, I. et al. A rapid colorimetric sensor for the detection of mercury in environmental samples employing 2 aminobenzohydrazide schiff base functionalized silver nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 1323, 140587 (2025).

Yılmaz, D. D., Demirezen, D. A. & Mıhçıokur, H. Colorimetric detection of mercury ion using chlorophyll functionalized green silver nanoparticles in aqueous medium. Surf. Interfaces 22, 100840 (2021).

Vyas, G., Bhatt, S. & Paul, P. Synthesis of calixarene-capped silver nanoparticles for colorimetric and amperometric detection of mercury (HgII, Hg0). ACS Omega 4(2), 3860–3870 (2019).

Varghese, A. M. & Karanikolos, G. N. CO2 capture adsorbents functionalized by amine–bearing polymers: A review. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 96, 103005 (2020).

Irani, M., Jacobson, A. T., Gasem, K. A. & Fan, M. Modified carbon nanotubes/tetraethylenepentamine for CO2 capture. Fuel 206, 10–18 (2017).

Zhou, G. et al. Adsorption application of tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) modified SBA-15@ MIL-101 (Cr) in carbon capture and storage (CCS). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 344, 112232 (2022).

Alshammari, M. S. Tetraethylenepentamine-grafted amino terephthalic acid-modified activated carbon as a novel adsorbent for efficient removal of toxic Pb (II) from water. Molecules 29(7), 1586 (2024).

Bušić, V. et al. Choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents as green effective medium for quaternization reactions. Molecules 27(21), 7429 (2022).

Khalkho, B. R. et al. L-cysteine modified silver nanoparticles for selective and sensitive colorimetric detection of vitamin B1 in food and water samples. Heliyon 6(2), e03423 (2020).

Mavani, K. & Shah, M. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by using sodium borohydride as a reducing agent. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol 2(3), 1–5 (2013).

Khatoon, U. T., Velidandi, A. & Rao, G. N. Sodium borohydride mediated synthesis of nano-sized silver particles: Their characterization, anti-microbial and cytotoxicity studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 294, 126997 (2023).

Biswas, A. Synthesis and characterization of colloidal silver nanoparticles of about 16 nm diameter by a chemical reduction method. Orient. J. Chem. 40(4), 1035 (2024).

Ibrahim, N. H., Taha, G. M., Hagaggi, N. S. A. & Moghazy, M. A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its environmental sensor ability to some heavy metals. BMC Chem. 18(1), 7 (2024).

Tewari, S. et al. Green synthesized AgNPs as a probe for colorimetric detection of Hg (II) ions in aqueous medium and fluorescent imaging in liver cell lines and its antibacterial activity. Discover Nano 19(1), 78 (2024).

Talodthaisong, C. et al. Highly selective colorimetric sensor of mercury (II) ions by andrographolide-stabilized silver nanoparticles in water and antibacterial evaluation. ACS Omega 8(44), 41134–41144 (2023).

Sangaonkar, G. M., Desai, M. P., Dongale, T. D. & Pawar, K. D. Selective interaction between phytomediated anionic silver nanoparticles and mercury leading to amalgam formation enables highly sensitive, colorimetric and memristor-based detection of mercury. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 2037 (2020).

Mwakalesi, A. J. & Nyangi, M. J. Colorimetric sensing of mercury in aqueous solutions using silver nanoparticles prepared from synadenium glaucescens root aqueous extract. Eng. Proc. 56(1), 182 (2023).

Sahu, M., Ganguly, M. & Sharma, P. Role of silver nanoparticles and silver nanoclusters for the detection and removal of Hg (ii). RSC Adv. 14(31), 22374–22392 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the General Authority for Defense Development (GADD) in Saudi Arabia for funding this research through project number (GADD_2024_01_0183).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Alharthi and A. Alswieleh designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the draft paper; and M. Alharthi, K. Alzahrani and A. Alswieleh revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alharthi, M.D., Alzahrani, K.E. & Alswieleh, A.M. Quaternized tetraethylenepentamine-capped AgNPs for selective and rapid colorimetric detection of mercury(II) in water. Sci Rep 15, 39850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23430-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23430-z