Abstract

To reduce the cogging torque (CT) and torque ripple (TR) of permanent magnet synchronous wind turbine (PMSWT) while ensuring the optimal overall performance of the generator, this paper proposes three improved structures and establishes a “parameter stratification-coordinated optimization” strategy based on the inner rotor salient pole permanent magnet synchronous wind turbine (IRSP-PMSWT). First, the electromagnetic characteristics of the three improved structures are analysed via finite element simulation, and the improved type B with the optimal comprehensive performance is screened out. Second, based on Spearman correlation analysis, the design parameters of type B are divided into two layers according to their degree of influence on the target performance: the first-layer key parameters are optimized for multiple objectives using the improved multi-objective slap swarm algorithm; the second-layer secondary parameters are subjected to single-objective refined optimization using the parameter sweep method. Simulation verification demonstrates that, compared with the traditional structure, the optimized type B achieves a reduction of 15.07% in TR and 55.71% in CT, an increase in torque density, and a reduction in the harmonic distortion rate of no-load back electromotive force (EMF). This realizes the coordinated optimization objectives of low disturbance, high utilization rate, and high density.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

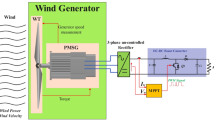

Against the backdrop of the global energy transition today, wind energy, as a core component of clean and renewable energy, relies on the performance improvement of permanent magnet synchronous wind turbine (PMSWT) for efficient utilization1,2. Owing to advantages such as high-power density and reliable operation, PMSWT are widely applied in medium and high-power wind power systems3,4. In countries with advanced wind power industries, the installed capacity of PMSWT has been increasing year by year, accompanied by continuous growth in investment in technological research and development5,6,7,8. Furthermore, with the advancement of smart grid construction, PMSWT are increasingly integrated into intelligent grid management systems, which improves the stability of their power output and grid-friendliness, providing a solid guarantee for large-scale, efficient, and stable wind power generation9,10. However, the interaction between the rotor structure of PMSWT and stator slots tends to generate CT; during load operation, TR is also formed due to the superposition of armature reaction. Both not only increase the operating vibration and noise of the generator but also reduce power quality, thereby restricting its application in high-precision wind power systems11,12 Therefore, how to coordinately suppress CT and TR while considering the overall performance of the motor has become a key technical challenge that major research institutions and enterprises are striving to overcome13,14,15,16.

In17, the generator’s CT was reduced through the design of unequal pole piece widths and unequal spacing, with reductions of 50% and 42% achieved respectively, but permanent magnet utilization was not considered. In18, CT was maximally reduced by 66.29% by optimizing the flux barrier shape and rotor slotting. However, this approach only targeted a single structural parameter and did not involve coordinated optimization of TR. In19, a binary evolutionary algorithm was used for topology optimization, which considered both mass and TR but failed to integrate specific structural improvements, leading to low optimization efficiency. In20 and21, the motor structure was modified in both studies, and a multi-objective genetic algorithm was adopted for parameter optimization to reduce TR and CT, but the designed motors were only applicable to electric vehicles. In summary, existing research on wind turbine mostly focuses on single structure or single algorithm, lacking a global design approach of structural improvement - parameter stratification - multi-objective coordinated optimization, making it difficult to simultaneously meet the comprehensive requirements of low disturbance, high utilization, and high performance.

To address the above shortcomings, this paper proposes an integrated scheme of structural improvement-parameter stratification coordinated optimization. First, three improved rotor structures are designed, and the optimal basic structure is selected through comparison of electromagnetic characteristics. Second, based on parameter correlation stratification, a hierarchical strategy combining the improved multi-objective slap swarm algorithm (IMOSSA) - parameter sweep method is adopted to optimize the first-layer and second-layer parameters respectively. Finally, multi-objective coordinated optimization of CT suppression, TR reduction, permanent magnet consumption reduction, and torque density improvement is achieved, providing a new method for the high-performance design of IRSP-PMSWT.

Generator topological structure

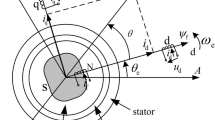

This paper takes a 10.75 MW IRSP-PMSWT as an example. The basic parameters of the generator are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagrams of four generator structures. IRSP-PMSWT is the most traditional inner-rotor salient-pole permanent-magnet synchronous wind turbine. Type A is the uniform Halbach array IRSP-PMSWT. Type B is the non-uniform three segment Halbach array IRSP-PMSWT. Type C is the non-uniform two segment Halbach array IRSP-PMSWT.

To ensure the rationality of the comparative analysis, the basic parameters of each generator, including its dimensions and electrical parameters, are set according to Table 1, while the generator structure parameters are shown in Table 2.

In Fig. 2, \({\beta _1}\) represents the central angle occupied by the main pole, and .\({\beta _2}\). represents the central angle occupied by the auxiliary pole, where \({{\rm P}_1}=\frac{{{\beta _1}}}{{{\beta _1}+{\beta _2}}}\)and \({{\rm P}_2}=\frac{{{\beta _2}}}{{{\beta _1}+{\beta _2}}}\). Figure 2a shows the structure of the Type A permanent magnet, with \({\beta _1}={\beta _2}\). Figure 2b shows the structure of the Type B permanent magnet, where the auxiliary pole is divided into two equal parts. Figure 2c shows the structure of the Type C permanent magnet, with \({\beta _1}>{\beta _2}\).

Electromagnetic characteristic analysis

Analysis of air gap magnetic density (AGMD)

The vector diagram of the AGMD is shown in Fig. 3.

In the formula, \({B_{\text{r}}}\) represents the radial AGMD, \({B_x}\) represents the component of the AGMD along the x axis, \({B_y}\) represents the component of the AGMD along the y axis, and \(\theta\) represents the included angle between the radial AGMD \({B_{\text{r}}}\) and the x axis.

The expression for the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the AGMD waveform is

In the formula, \({B_{ri}}\) is the amplitude of the i-th harmonic of the radial AGMD, where \(i=2,3,...,10\);\({B_{r1}}\) is the amplitude of the fundamental wave of the radial air-gap magnetic flux density.

The Halbach array makes use of the different magnetization directions of the permanent magnets to enhance the magnetic field on one side of the air gap and weaken it on the other side, thus effectively increasing the magnetic density in the useful area of the air gap. Compared with the two-segment array, the non-uniform three-segment Halbach array can better regulate the magnetic field, increase the air-gap magnetic density, and reduce the harmonic content. Figure 4 shows the AGMD waveforms of four types of generator structures. From the figure, it can be seen that the root mean square (RMS) value of Type B is the largest, which is 0.587 T, while that of Type A is the smallest, being 0.543 T. The RMS values of Type C and IRSP-PMSWT are 0.582 T and 0.555 T respectively. Figure 5 shows the radial component of the air-gap magnetic flux density. The value of IRSP-PMSWT is 0.550 T, that of Type A is 0.539 T, Type B is 0.584 T, and Type C is 0.579 T. Figure 6 presents the Fourier decomposition results of the radial AGMD. For all four structures, the odd order harmonics of the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th orders are large, while the even-order harmonics are small. The THD of IRSP-PMSWT is 15.23%. For Type A, the amplitudes of the 1st, 3rd, and 7th harmonics are the smallest, but the amplitudes of the 5th and 9th harmonics are quite large. Its THD reaches 24.21%, which is 11.98% higher than that of the traditional structure. The THD of Type B is 10.86%, 4.37% smaller than that of the traditional structure. It has the smallest THD and the best sinusoidal waveform. The THD of Type C is 14.04%, 1.19% smaller than that of the traditional structure.

Electromagnetic torque analysis

Electromagnetic torque is a key physical quantity of a generator and is closely related to the output power of the generator. The electromagnetic TR can reflect the quality of the generator’s operation22,23. The non-uniform three-segment Halbach array makes the interaction among the stator current, the magnetic field of the permanent magnets, and the rotor magnetic resistance more sufficient, thus generating a larger electromagnetic torque. The non-uniform three-segment Halbach array can make better use of the salient-pole effect of the rotor, enabling the magnetic resistance torque to be more fully exerted. Figure 7 shows the electromagnetic torque waveforms of the four structures. Further analysis of Fig. 7 yields Fig. 8, which shows the average electromagnetic torque, and Fig. 9, which shows the electromagnetic TR. Compared with the traditional structure, the structures of Type B and Type C are improved in terms of both electromagnetic torque and TR, while the Type A structure shows the opposite, with worse performance in both electromagnetic torque and TR.

Analysis of CT

The CT is generated by the interaction between the magnetic field produced by the permanent magnets and the teeth and slots of the stator core. When the permanent magnets of the rotor are aligned with the teeth of the stator, the magnetic resistance of the air-gap magnetic circuit is relatively small, and the magnetic permeance is relatively large. When the permanent magnets of the rotor are in the middle position of the stator slots, the magnetic resistance of the air-gap magnetic circuit is relatively large, and the magnetic permeance is relatively small. As the rotor keeps rotating, the air-gap magnetic permeance fluctuates periodically between large and small values. The magnetic field energy of the permanent magnets is closely related to the air-gap magnetic permeance. The periodic change of the magnetic permeance will cause the magnetic field energy of the permanent magnets to change periodically as well, and this energy change leads to the generation of the CT. Through finite element simulation, the CT of the four structures are shown in Fig. 10.

The maximum value of the CT of IRSP-PMSWT is 0.85\(\:\text{k}\text{N}\cdot\:\text{m}\). The CT of Type A, Type B, and Type C are 1.13 \(\:\text{k}\text{N}\cdot\:\text{m}\), 0.625 \(\:\text{k}\text{N}\cdot\:\text{m}\), and 0.81 \(\:\text{k}\text{N}\cdot\:\text{m}\) respectively. The CT performance of the Type B structure is better than that of the other structures. Through the above analysis of the four structures, the Type B structure is selected for further optimization in this paper.

MOSSA-multi-objective hierarchical optimization based on slap behaviour

The For the multi variable, strongly coupled, and non-linear mathematical programming problem in the design of PMWT, many studies have done a great deal of work on aspects such as stator slot shape optimization and rotor permanent magnet optimization. However, the screening and analysis of the influence of the stator and rotor on the generator’s performance and efficiency are not thorough enough, and there is a lack of analysis from the perspective of simultaneous optimization of both the stator and rotor24,25,26.

The multi-objective slap swarm algorithm (MOSSA) is inspired by the group swimming behavior of slaps in the ocean. In this algorithm, the slap group is divided into leaders and followers. The followers update their positions based on the positions of the leaders and the previous individuals27. In this way, the coordinated swimming of the group is achieved, and the algorithm approaches the overall optimal solution while performing single objective optimization28. Although MOSSA can avoid local optima to some extent, in certain cases, it may still converge prematurely to a locally optimal non-dominated solution set, thus missing the global optimal solution or better non-dominance29,30. To minimize the occurrence of this phenomenon, this paper proposes an improvement to MOSSA by integrating the adaptive weight factor and the Levy flight perturbation strategy into MOSSA, namely AWFLFPS-MOSSA.

Adaptive weight factor theory

In the initial stage of iteration, in order to enhance the global search ability of the algorithm and effectively avoid the risk of getting trapped in local optimal solutions, the position update range of the leader needs to be set relatively large31. As the iteration progresses and enters the later stage, to ensure the accuracy of the search results, it is necessary to shrink the position update range of the leader32,33. Regarding followers, in the early stage of iteration, the influence of the previous - generation leader on them should be emphasized; while in the later stage of iteration, this influence needs to be gradually weakened. Based on the above considerations, we introduce an adaptive weight factor.

In the formula, \(\omega\) is the adaptive weight factor; \({\omega _{\hbox{max} 1}}\) and \({\omega _{\hbox{max} 2}}\) are the maximum values of the adaptive weight factor, which are taken as 1.5 and 0.7 respectively. \({\omega _{\hbox{min} 1}}\) and \({\omega _{\hbox{min} 2}}\) are the minimum values of the adaptive weight factor, which are taken as 1 and 0.5 respectively. B is the iteration weight factor, n is the current number of iterations, and N is the total number of iterations.

Levy flight perturbation

Levy flight perturbation refers to using the characteristics of Levy flight to perturb the current solution, thereby increasing the diversity of solutions and preventing the algorithm from prematurely converging to local optimal solutions34,35,36. To generate random step sizes that follow the Levy distribution, the Mantegna algorithm is commonly used. This algorithm generates the Levy flight step size in the following way:

First, define two random variables u and v that follow the normal distribution.

\(\beta\) is the index parameter of Levy flight, which is usually taken between (0, 2). The Levy flight step size s is

The position of the leader in the original MOSSA is…

In the formula, \(x_{j}^{i}\) represents the position of the ith leader in the jth dimension, \({F_j}\) represents the position of the food source in the j-th dimensional space; \({c_2}\) and \({c_3}\) are random coefficients that maintain the search space, and both take values between [0, 1], where \({c_2}\) determines the search step-size of the current spatial position, and \({c_3}\) determines the search direction; \({c_1}\) is an important parameter for balancing the global exploration and local exploitation stages; t is the current number of iterations, and T is the total number of iterations.

Position of the followers:

In the formula, \(y_{j}^{i}\) represents the position of the i-th follower in the j-th dimension.

The position of the leader in the improved AWFLFPS-MOSSA is

The position of the followers in the improved AWFLFPS-MOSSA becomes

Algorithm testing

The DTLZ2 function is used to evaluate the performance of the MOSSA and AWFLFPS-MOSSA algorithms. The MOSSA and AWFLFPS-MOSSA algorithms are each run 30 times repeatedly. The convergence and diversity of the algorithms are judged by introducing the Generation Distance (GD) and Spacing metric (SP)37,38,39,40.

In the formula, A is the approximate Pareto solution set obtained by the algorithm, \({L_i}\) is the Euclidean distance from the i-th solution in A to the nearest solution in the Pareto optimal solution set, \(\left| A \right|\) is the number of solutions in A, and \(\overline {L}\) is the average of the minimum Euclidean distances of all individuals.

The algorithm testing results are shown in Fig. 11. The means and standard deviations of GD and SP of AWFLFPS-MOSSA are smaller than those of MOSSA. It can be seen that AWFLFPS-MOSSA performs better than MOSSA in terms of convergence and diversity. The optimization process based on AWFLFPS-MOSSA is shown in Fig. 12.

Selection of optimization objectives and optimization parameters

To further reduce the CT of the generator, minimize the TR, enhance the operational stability of the generator, and extend its service life, this study selects the peak value of CT \({T_{cog}}\), the average electromagnetic torque \({T_{avg}}\), the TR \({T_r}\), the volume of the permanent magnet \({V_{pm}}\), and the fundamental wave amplitude of the no-load back EMF \({E_m}\) as the optimization objectives.

The parameters in Table 3 are used as the parameters to be screened and optimized for the correlation analysis of the optimization objectives. The highly correlated parameters are selected as the first layer optimization parameters, and the AWFLFPS-MOSSA is used for multi-objective optimization. The remaining parameters are used as the second layer optimization parameters, and the single-objective parameter scanning optimization is carried out. The objective function is

Figure 13 is a schematic diagram of the stator slot. The relationship between the stator slot width \({B_{s1}}\) and \({B_{s2}}\) is

In the formula, \(\:\text{k}\) is the proportionality coefficient, with a value of 1.6.

Parameter correlation analysis

For the parameters with a linear relationship, this paper selects Pearson correlation analysis to analyse the parameters. The correlation coefficient is obtained by calculating the ratio of the covariance between the parameters to the product of the standard deviations of the variables41,42.

In the formula, r is the Pearson correlation coefficient, x and y are two parameters, \(\overline {x}\) and \(\overline {y}\) are the mean values, and s is the number of parameters.

For the parameters with a non-linear relationship, this paper selects the Spearman correlation analysis to analyse the parameters. The correlation coefficient is reflected through the rank relationship between the two parameters.

In the formula, \({r_s}\)is the Spearman correlation coefficient, and \({d_i}\) is the larger difference between the corresponding ranks of parameters x and y.

Finally, the correlation coefficients between the parameters in Table 3 and the peak value of CT \({T_{{\text{cog}}}}\), the fundamental wave amplitude of no load back EMF\({E_m}\), the average electromagnetic torque \({T_{avg}}\), and the TR \({T_r}\)are obtained as shown in Fig. 14.

Since \({V_{pm}}\) is only related to \({\beta _1}\) and \({H_m}\), the Spearman correlation coefficient for \({V_{pm}}\) is not calculated in Fig. 14. The calculation formula for \({V_{pm}}\) is as follows:

In the formula, \({D_{si}}\) is the inner diameter of the stator core, \({L_a}\) is the length of the core, and p is the number of pole pairs.

In order to comprehensively measure the correlation between each optimization parameter and the optimization target, the comprehensive correlation degree between each parameter and the optimization target was calculated. The calculation formula is as follows.

In the formula, \({\rho _{mi}}\) represents the comprehensive correlation degree of each optimization parameter, \({\rho _{ij}}\) is the correlation coefficient of the ith optimization parameter with respect to the jth optimization target, and u is the number of optimization targets.

According to the criteria for judging the strength of correlation, when \(\left| {{\rho _{mi}}} \right| \leqslant 0.3\), it is considered to have a low correlation. As can be seen from Fig. 15, parameters \({P_1}\), \({H_{\text{m}}},\delta\) and \({B_{{\text{s}}1}}\) have relatively high correlations. Therefore, they are used as the first layer optimization parameters for multi-objective optimization. Parameters \(\theta ,{H_{s0}}\) and \(B{}_{{{\text{s}}0}}\) have low correlations and are used as the second layer optimization parameters.

Polynomial response surface model based on response surface method

The Box Behnken Design (BBD) response surface method is used to establish a polynomial response surface model for the first layer optimization. The 29 sets of experimental data corresponding to the four optimization parameters are shown in Table 4.

The formula for the second order polynomial response surface model is as follows:

In the formula, \({x_i}\) and \({x_j}\) represent independent variables;\({Q_0}\) is the constant term, \({Q_i}\) is the coefficient of the first order term; \({Q_{ii}}\) is the coefficient of the second order term; \({Q_{ij}}\) is the coefficient of the interaction term; ε is the random error term.

The formula for the third order polynomial response surface model is as follows:

In the formula, \({Q_{iii}}\) is the coefficient of the cubic term, which is used to describe the cubic effect of the independent variable \({x_i}\); \({Q_{iji}}\) is the interaction term coefficient, representing the interaction effect among the independent variables \({x_i}\), \({x_j}\), and \({x_i}\); \({Q_{ijm}}\) is also an interaction term coefficient, indicating the interaction effect among the independent variables \({x_i}\), \({x_j}\), and \({x_m}\).

Finally, the target equations are obtained as shown in Eq. (25).

To determine whether the model fitting effect is close to the true value, this paper introduces the coefficient of determination \({R^2}\).

First, calculate the total sum of squares \(SST\).

In the formula, \({y_i}\) represents the observed values of the dependent variable, \(\bar {y}\)represents the mean value of the dependent variable, and n represents the number of dependent variables.

Then calculate the sum of squares of regression.

In the formula, \({\hat {y}_i}\)represents the predicted values of the dependent variable.

Coefficient of determination \({R^2}\)

By calculation, the coefficients of determination for cogging torque\({T_{cog}}\), average electromagnetic torque\({T_{a\nu g}}\), TR \({T_r}\), and the fundamental amplitude of no load back EMF\({E_m}\) are 0.985, 0.981, 0.996, and 0.999 respectively, all of which are very close to 1. This indicates that the constructed model is reasonable. Figure 16 shows the response surface model fitted according to Eq. (25).

First layer parameter optimization

During the implementation of the program in Matrix Laboratory R2021a (https://www.mathworks.com/), both the population size and the number of iteration generations are set to 200. The population size is the same as the number of iterations, both taking the value of 200. The variables are \({\beta _1}\),\({H_m}\),\(\delta\)and \({B_{s1}}\). Optimization is performed on the functions \({T_{cog}}\),\({T_{avg}}\),\({T_r}\),\({E_m}\)and \({V_{pm}}\) respectively. The obtained Pareto front is shown in Fig. 17. In this figure, the volume of the small spheres corresponds to \({V_{pm}}\), and the depth of the sphere colour represents \({E_m}\). Finally, the simulation results of Type B are used as the constraint conditions for the optimization objectives to screen the obtained solutions. The constraint formulas are as follows:

Combine Eq. (29) and Fig. 17 to screen the solutions. To obtain the optimal solution, perform normalization and weighting operations on the screened solutions. Normalization usually maps the values of variables to the interval [0, 1], and the calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, x represents the original variable, \({x_{\hbox{min} }}\) represents the minimum value of the variable, and \({x_{\hbox{max} }}\) represents the maximum value of the variable. In this paper, the normalized values of \({T_{cog}}\), \({T_{avg}}\),\({T_r}\),\({E_m}\), and \({V_{pm}}\) are \(T_{{cog}}^{\prime }\), \(T_{{avg}}^{\prime }\), \(T_{r}^{\prime }\), \(E_{m}^{\prime }\), and \(V_{{pm}}^{\prime }\) respectively. Among them, the larger \({T_{avg}}\) and \({E_m}\) are, the better, so positive normalization is carried out. For the generator, the smaller \({T_{cog}}\), \({T_r}\), and \({V_{pm}}\) are, the better. Therefore, reverse normalization is adopted. The weight coefficients corresponding to \({T_{cog}}\), \({T_{avg}}\), \({T_r}\), \({E_m}\), and \({V_{pm}}\) are \({f_1}\), \({f_2}\), \({f_3}\), \({f_4}\), and \({f_5}\) respectively. In this paper, the weight coefficients are taken as 0.2, 0.25, 0.25, 0.1, and 0.2 respectively. The comparison of the parameter values of the first layer before and after optimization is shown in Table 5.

Second layer parameter optimization

On the basis of the first layer optimization, parameter scanning is carried out on \({T_{cog}}\) and \({T_r}\) with \(\theta\), \({H_{{\text{s}}0}}\), and \({B_{{\text{s}}0}}\) as variables.

As can be seen from Fig. 18a, the overall trend of \({T_{avg}}\) is that it decreases as \({H_{s0}}\) increases, and it first increases and then decreases as C increases. The maximum value occurs at \({B_{s0}}\) = 9 mm and \({H_{s0}}\) = 1.5 mm. As can be seen from Fig. 18b, the overall trend of \({T_r}\) is that it increases as \({H_{s0}}\) increases and decreases as \({B_{s0}}\) increases. The minimum value occurs at \({B_{s0}}\)= 12 mm and \({H_{s0}}\) = 1.5 mm. For \({H_{s0}}\), the optimal point \({H_{s0}}\) = 1.5 mm is selected. For \({B_{s0}}\), \({T_{avg}}\) is given priority consideration. Therefore, finally, \({B_{s0}}\) = 9 mm and \({H_{s0}}\) = 1.5 mm are selected.

As can be seen from Fig. 19, when \({B_{s0}}\) = 9 mm and \({H_{s0}}\)= 1.5 mm, the overall trend of \({T_{avg}}\) is that it first increases and then decreases as \(\theta\) increases, and the maximum value is around \(\theta\) = 50°. The overall trend of \({T_r}\)is that it decreases as \(\theta\)increases, and the minimum value occurs when \(\theta\)= 75°. Considering the comprehensive situations of \({T_{avg}}\)and \({T_r}\), finally \(\theta\) = 55° is selected. After the second layer optimization, the values of the second layer parameters are obtained as shown in Table 6.

Although the convergence speed of the AWFLFPS-MOSSA algorithm has been improved based on the MOSSA algorithm, the overall computational complexity has increased due to the incorporation of the adaptive weight factor and Levy flight perturbation. Moreover, although the AWFLFPS-MOSSA algorithm coordinates and optimizes the parameters of the stator and rotor simultaneously, when the algorithm iterates to the neighborhood of the global optimum, the long-distance jump of the algorithm may cause the parameters to suddenly jump out of the high-precision convergence region, forcing the algorithm to re-explore the low-quality solution space. Sensitive parameters such as the pole arc coefficients of the main and auxiliary magnetic poles will mutate during the iteration of the AWFLFPS-MOSSA algorithm, leading to the distortion of the air-gap magnetic density waveform and an increase in the torque ripple, which results in the need to spend additional time for re-solving.

Analysis of optimization results

A comparative analysis is conducted among the optimized Type B, the pre-optimized Type B, Type A, and ISRSP-PMSWT. When a current excitation is applied to the generator, the image of the variation of the average electromagnetic torque \({T_{avg}}\)of the generator with the current angle under the rated current is shown in Fig. 20. When the current angle is 130°, the generator has the maximum average output torque. Figure 21 shows the waveform diagram of the electromagnetic torque. Further analysis of Fig. 21 yields Fig. 22, which depicts the average electromagnetic torque, and Fig. 23, which shows the electromagnetic TR. It can be seen from the figures that the optimized Type B generator has a maximum average electromagnetic torque of 322.7 kN⋅m and a minimum TR of 6.8%. The electromagnetic torque characteristics of the Type B generator is superior to those of the other three structures.

The comparison diagram of the CT of the four types of generators is shown in Fig. 24. After optimization, the peak value of the CT of the generator is reduced. The CT of the optimized Type B is 376.49 N·m, that of the non-optimized Type B is 625 N·m, that of the IRSP-PMSWT is 850 N·m, and that of Type A is 1130 N·m.

It can be seen from Fig. 25, the comparison diagram of no load back EMF, that the waveform of the optimized Type B generator is closer to a smooth sine wave, indicating an improved waveform. The waveform distortion rate is significantly reduced.

Conclusion

In this paper, improvements are made based on the structure of the IRSP-PMSWT. Type A uniform Halbach magnetization structure, Type B non-uniform three segment Halbach magnetization structure, and Type C non-uniform two segment Halbach magnetization structure is proposed. First, electromagnetic characteristic analyses are carried out for these four structures, highlighting the advantages of the three structures of Type A, Type B, and Type C. Subsequently, the Pearson and Spearman methods are used to calculate the correlations between parameters, and the parameters are stratified. For the first layer parameters, the improved slap swarm algorithm AWFLFPS-MOSSA is employed for multi-objective optimization; for the second layer parameters, parameter scanning is used for optimization. Finally, the simulation results show that compared with the traditional structure generator, the outer rotor permanent magnet synchronous generator with the non-uniform Halbach array proposed in this paper reduces the usage of permanent magnets, increases the torque density, enhances the fundamental wave amplitude of the no load back EMF, reduces the harmonic distortion rate, and decreases the TR and CT by 15.07% and 55.71% respectively. The electromagnetic performance of the generator is significantly improved.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Wang, J., Xu, Z., Xing, Z., Liu, Y. & Ji, W. Study on electromagnetic characteristics of high-temperature superconducting axial-flux permanent-magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 34(8), 1–4 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Research on control strategy of hybrid superconducting energy storage based on reinforcement-learning algorithm. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 34(8), 1–4 (2024).

Winterborne, D., Stannard, N., Sjöberg, L. & Atkinson, G. An air-cooled YASA motor for in-wheel electric vehicle applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56(6), 6448–6455 (2020).

Aydin, M. & Gulec, M. A. New coreless axial-flux interior permanent-magnet synchronous motor with sinusoidal rotor segments. IEEE Trans. Magn. 52(7), 1–4 (2016).

Fang, L., Li, D. & Qu, R. A. Novel permanent magnet vernier machine with coding-shaped tooth. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69(6), 6058–6068 (2022).

Xing, F., Zhao, W. & Kwon, B. Design and optimization of a novel asymmetric rotor structure for a PM-assisted synchronous reluctance machine. IET Electr. Power Appl. 13(5), 573–580 (2019).

Wang, C., Han, J., Zhang, Z., Hua, Y. & Gao, H. Design and optimization analysis of coreless stator axial - flux permanent magnet in-wheel motor for unmanned ground vehicle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrific. 8(1), 1053–1062 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Driving-cycle-oriented design optimization of a permanent magnet hub motor drive system for a four-wheel-drive electric vehicle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrific. 6(3), 1115–1125 (2020).

Tong, W., Li, S., Pan, X., Wu, S. & Tang, R. Analytical model for cogging torque calculation in surface-mounted permanent magnet motors with rotor eccentricity and magnet defects. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 35(4), 2191–2200 (2020).

Sun, M., Tang, R., Han, X. & Tong, W. Analysis and modeling for open circuit air gap magnetic field prediction in axial flux permanent magnet machines. Proc. Chin. Soc. Elect. Eng. 38(5), 1525–1533 (2018).

Wang, H. L. & Li, X. Winding design and analysis for a disc - type permanent - magnet synchronous motor with a PCB stator. Energies 11(12), 3383 (2018).

Taran, N., Ionel, D. M. & Dorrell, D. G. Two-level surrogate-assisted differential evolution multi-objective optimization of electric machines using 3-D FEA. IEEE Trans. Magn. 54(11), 1–5 (2018).

Zhang, H., Hua, W., Gerada, D., Xu, Z. & Gerada, C. Analytical model of modular spoke - type permanent magnet machines for in-wheel traction applications. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 35(3), 1289–1300 (2020).

Xiaoyuan, W., Peng, G. & Gengji, W. The design of halbach array permanent magnet for in-wheel motor. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Elect. Mach. Syst. 1252-1255 (2013).

Aydin, M., Huang, S. & Lipo, T. A. Torque quality and comparison of internal and external rotor axial flux surface - magnet disc machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53(3), 822–830 (2006).

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S. & Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Tran Evol. Comput. 6(2), 182–197 (2002).

Dai, B., Nakamura, K., Suzuki, Y., Tachiya, Y. & Kuritani, K. Cogging torque reduction of integer gear ratio axial-flux magnetic gear for wind-power generation application by using two new types of pole pieces. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58(8), 1–5 (2022).

Cao, Z. & Liu, J. Cogging torque reduction for outer rotor interior permanent magnet synchronous motor. IECON., 2689 - 2693 (2020).

Ruzbehi, S. & Hahn, I. Topology optimization of a PM synchronous machine based on novel metaheuristic algorithm for lower cogging torque and magnet Volume. ICIT. 1–5 (2022).

Ning, S. et al. A novel double stator hybrid-excited Halbach permanent magnet flux-switching machine for EV/HEV traction applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 18636 (2024).

Srikhumphun, P. et al. Design optimization of a novel dual-skewed Halbach-array double-sided axial flux permanent magnet motor for electric vehicles. Sci. Rep. 15, 25905 (2025).

Taran, N., Rallabandi, V., Heins, G. & Ionel, D. M. Coreless and conventional axial-flux permanent-magnet motors for solar cars. IEEE Trans. Ind. App. 54(6), 5907–5917 (2018).

Hämäläinen, H., Pyrhönen, J., Nerg, J. & Talvitie, J. AC resistance factor of Litz-wire windings used in low-voltage high-power generators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 61(2), 693–700 (2014).

Rallabandi, V., Taran, N., Ionel, D. M. & Eastham, J. F. Coreless multidisc axial flux pm machine with carbon nanotube windings. IEEE Trans. Magn. 53(6), 1–4 (2017).

Wang, X., Pang, W., Gao, P. & Zhao, X. Electromagnetic design and analysis of axial flux permanent magnet generator with unequal-width PCB winding. IEEE Access. 7, 164696–164707 (2019).

Geng, W., Zhang, Z. & Li, Q. High torque density fractional-slot concentrated-winding axial-flux permanent-magnet machine with modular SMC stator. IEEE Trans. Ind. App. 56(4), 3691–3699 (2020).

Vansompel, H., Sergeant, P. & Dupre, L. A. Multilayer 2-D-2-D coupled model for eddy current calculation in the rotor of an axial-flux PM machine. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 27(3), 784–791 (2012).

Winterborne, D., Stannard, N., Sjöberg, L. & Atkinson, G. An air-cooled YASA motor for in-wheel electric vehicle applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. App. 56(6), 6448–6455 (2020).

Shen, Y. & Zhu, Z. Q. Analytical prediction of optimal split ratio for fractional-slot external rotor PM brushless machines. IEEE Trans. Magn. 47(10), 4187–4190 (2011).

Pang, Y., Zhu, Z. Q. & Howe, D. Analytical determination of optimal split ratio for permanent magnet brushless motors. IEE Proc.-Elect. Power Appl. 153(1), 7-13 (2006).

Joseph, V. R. Space-filling designs for computer experiments: A review. Qual. Eng. 28(1), 28–35 (2016).

Li, M., Gabriel, F., Alkadri, M. & Lowther, D. A. Kriging-assisted multi-objective design of permanent magnet motor for position sensorless control. IEEE Trans. Magn. 52(3), 7001904 (2016).

Kim, K. C., Lee, J., Kim, H. J. & Koo, D. H. Multiobjective optimal design for interior permanent magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 45(3), 1780–1783 (2009).

Parasiliti, F., Villani, M., Lucidi, S. & Rinaldi, F. Finite-element-based multiobjective design optimization procedure of interior permanent magnet synchronous motors for wide constant-power region operation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 59(6), 2503–2514 (2012).

Mahmoudi, A., Kahourzade, S., Rahim, N. A. & Ping, H. W. Design, analysis, and prototyping of an axial-flux permanent magnet motor based on genetic algorithm and finite-element analysis. IEEE Trans. Magn. 49(4), 1479–1492 (2013).

Liu, X., Chen, H., Zhao, J. & Belahcen, A. Research on the performances and parameters of interior PMSM used for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(6), 3533–3545 (2016).

Liu, G., Xu, G., Zhao, W., Du, X. & Chen, Q. Improvement of torque capability of permanent - magnet motor by using hybrid rotor configuration. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 32(3), 953–962 (2017).

Zhao, W., Xing, F., Wang, X., Lipo, T. A. & Kwon, B. I. Design and analysis of a novel PM-assisted synchronous reluctance machine with axially integrated magnets by the finite-element method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 53(6), 1–4 (2017).

Lipo, T. A. & Liu, W. Comparison of AC motors to an ideal machine part I—conventional AC machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56(2), 1346–1355 (2020).

Momen, F., Rahman, K. & Son, Y. Electrical propulsion system design of chevrolet bolt battery electric vehicle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 55(1), 376–384 (2019).

Seo, J. M., Ro, A. R., Kim, R. E. & Seo, J. Hybrid analysis method considering the axial flux leakage in spoke-type permanent magnet machines. IEEE Trans. Magn. 56(9), 1–6 (2020).

Li, Y., Yang, H., Lin, H., Fang, S. & Wang, W. J. E. A novel magnet- axis-shifted hybrid permanent magnet machine for electric vehicle applications. Energies 12(4), 641–653 (2019).

Acknowledgements

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by Revitalization Talents Program of Liaoning Province, grant number XLYC2008005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zuoxia Xing and Dongrui Wang, Conceptualization; Dongrui Wang, methodology; Dongrui Wang, software; Dongrui Wang, Wei Li and Zuoxia Xing, validation; Changjie Sun, formal analysis; Dongrui Wang, investigation; Dongrui Wang and Rui Xu, resources; Dongrui Wang, data curation; Dongrui Wang, writing—original draft preparation; Dongrui Wang, writing—review and editing; Dongrui Wang, visualization; Wei Li, supervision; Wei Li, project administration; Zuoxia Xing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, D., Xing, Z., Li, W. et al. Study on the suppression of CT and TR of IRSP PMSWT based on structural improvement and hierarchical collaborative optimization. Sci Rep 15, 39871 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23441-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23441-w