Abstract

Narrative discourse production is among the most important aspects of human communication. This study focuses on the impact of healthy aging on three major aspects of narrative production: productivity skills (in terms of words produced, speech rate, and % of informative words), the use of subjectivity markers (i.e., in our study those adjectives and adverbs that signal the narrator’s personal stance, emotions, evaluations, or perspective), and the spontaneous tendency to describe emotions during storytelling. We also investigated the relationship between these three features of narrative production and Theory of Mind skills within the context of the effects of healthy aging on these measures. Ninety participants were divided into three age groups: young adults, older adults, and senior-old adults. Their speech samples were analyzed using a multilevel discourse analysis. Among subjectivity markers, older adults produced more modalizers (i.e., adjective and adverbs reflecting the speaker’s evaluation about the degree of certainty or doubt of what is being told) than younger participants. In contrast, the use of emotion descriptors significantly dropped in senior-old adults. Furthermore, performance on Theory of Mind tasks correlated with the spontaneous tendency to describe emotions and produce informative words during storytelling but not with the production of subjectivity markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Successful aging is a complex concept to define. However, as the aging population continues to grow and life expectancy increases, it becomes increasingly important to study aging and its (potential, at least) effects on both individuals and their social relationships. Communicative skills can be examined in various ways. Among these, the ability to produce contextually appropriate words during narrative production is particularly relevant1.

Studies focusing on lexical abilities in the context of narrative discourse production suggest that productivity skills can be differentially affected by aging. While no age-related differences are typically reported in the number of words produced by younger and older individuals, other aspects of lexical production are negatively influenced by aging1,2,3. For example, it has been shown that speech rate declines linearly, whereas the ability to produce informative words and to monitor the ongoing organization of the narrative follows a nonlinear trajectory, with significant deterioration occurring after age 751,2,3. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet examined the effects of healthy aging on two additional aspects that characterize the production of communicatively adequate narratives: the expression of subjectivity and the ability to describe characters’ emotions during storytelling. The expression of subjectivity refers to the ways in which an individual’s personal perspective, beliefs, and experiences are embedded in their discourse. This may occur intentionally (e.g., through the use of evaluative comments4) or even unintentionally. In discourse production, the speaker’s subjectivity influences content selection, discourse structure, and linguistic style, reflecting their point of view5. It is therefore important to investigate how aging affects this crucial ability. Similarly, the ability to describe emotions during storytelling remains largely unexplored. Emotions play a crucial role in daily life and can be conveyed both explicitly and implicitly–for example, through prosody or through verbal expressions such as interjections that do not directly label emotional states. Storytelling may create or reinforce associations between certain situations and specific emotions6. Although the ability to describe emotions displayed by characters during storytelling has not been addressed in previous studies, several investigations have shown that identifying and expressing emotions can become more challenging with age7,8,9.

Given the lack of previous studies exploring the potential effects of aging on the ability to express subjectivity in narrative discourse, this study focuses on adjectives and adverbs (including adjectival and adverbial locutions), adopting the classification system proposed by Kerbrat-Orecchioni5. According to5, subjectivity can be expressed through a large number of communicative tools, including words that fall into the following four categories: evaluative non-axiological words, evaluative axiological words, affective words, and modalizers. Evaluative non-axiological words convey the speaker’s personal evaluation without expressing any value-laden positive or negative judgement, nor any emotion. For example, they may describe physical properties, such as the adjectives small, tall, or dark. In contrast, evaluative axiological words imply a value judgement, often grounded in social, cultural, or ethical norms. This judgement usually carries either a positive or negative connotation (e.g., good, bad, or ugly). Affective words, on the other hand, express the speaker’s emotional involvement, conveying their emotional state toward a referent or situation within a discourse. For example, in a specific context, the phrase the poor boy may not denote a condition of poverty but rather express the speaker’s affective stance or emotional concern. Lastly, modalizers reflect the speaker’s evaluation about the degree of certainty or doubt of what is being said. Examples include maybe, probably, surely, really, actually, and in fact. To the best of our knowledge, this categorization has not yet been applied to the analysis of how linguistic production evolves across the adult lifespan in the context of healthy aging.

In this study, the analysis also included adjectives and adverbs used to describe the emotions of the characters depicted in the narratives. We therefore distinguished between proper affective adjectives and adverbs, which reflect the speaker’s emotional involvement, and those used to describe the emotional states and reactions of the characters (e.g., the old man looks angry when the pot falls on his head or the woman’s husband seems sad when she leaves). According to Kerbrat-Orecchioni5, this latter type of affective word is based on what she terms “interpretive subjectivity”. To avoid confusion with affective words that express the speaker’s personal feelings, we refer to these adjectives and adverbs that describe the emotions of characters as emotion descriptors. In this study, we treated them as a separate category, distinct from subjectivity markers. Finally, we also included occurrences of first-person singular pronouns referring to the speaker, both implicitly and explicitly. In Italian, the grammatical subject does not need to be overtly expressed; thus, implicit references may occur, as in “penso che la donna stia versando del caffè” (“[I] think the woman is pouring coffee”). Explicit references include examples such as “mi sembra che i due facciano pace” (“It seems to me that the two are making peace”); or “io non capisco cosa stia facendo la persona sullo sfondo” (“I don’t understand what the person in the background is doing”). These pronouns differ from the subjectivity markers discussed earlier, as they belong to the category of deictics. However, they were included in the analysis because the use of the first person represents an additional communicative device that highlights the speakers’ presence and, consequently, their subjectivity as the referent of the pronoun5. Notably, the use of such pronouns is often associated with utterances that are not directly relevant to the description of the story. Since these utterances may be perceived as tangential or filler relative to the main narrative flow, the use of first-person singular pronouns may be linked to increased off-topic verbosity—an aspect frequently observed in the discourse of older individuals1,2,3.

While the ability to produce contextually appropriate narrative discourse is essential for communication, it is not sufficient on its own. Successful interaction also depends on a key aspect of social cognition—namely, the capacity to attribute mental states to oneself and to others—commonly referred to as Theory of Mind (ToM;10). Growing evidence suggests that this is a multidimensional construct comprising both cognitive and affective components11. The cognitive component involves understanding and attributing mental processes such as beliefs, thoughts, and intentions to others. The affective component pertains to recognizing and interpreting others’ emotional experiences and feelings. Over time, several tasks have been designed to assess ToM skills. Among these, one of the most widely used is the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET)12. Recently, concerns have been raised about this task, as it has been suggested that performance on the RMET may reflect emotion recognition rather than ToM abilities (e.g.,13). Nonetheless, this task has often been referred to as a measure of affective ToM (e.g.,14,15). Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that it requires also the attribution of non-emotional mental states, and, therefore, reflects even cognitive ToM skills16,17. Other ToM tasks are the Strange Stories task18, and second-order ToM tasks requiring individuals to answer questions about different stories (e.g., John and Mary19 and Peter’s Birthday20). In recent years, accumulating evidence has indicated that healthy aging affects both components, with significant difficulties emerging after the age of 70—particularly on tasks requiring second-order ToM skills15,21,22,23,24. For example, Fischer et al.23 assessed cognitive ToM using the Strange stories task18 and affective ToM using the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test12. In both tasks, adults aged 64–87 performed worse than younger adults aged 17–27 years. Furthermore, Ruitenberg et al.24 demonstrated that these age-related effects are particularly evident on tasks requiring participants to generate second-order, rather than first-order, inferences. First-order inferences involve the ability to represent another person’s mental state and compare it with one’s own, whereas second-order inferences require understanding one person’s mental state in relation to the mental state of another.

Overall, the available literature suggests that several key abilities are significantly affected by healthy aging: the ability to produce words fluently (as reflected in speech rate), to select and use communicatively appropriate words (in terms of lexical informativeness), and to attribute mental states to others (both cognitive and affective ToM). However, there is still a lack of information regarding the potential effects of aging on other crucial aspects of narrative production, such as the expression of subjectivity and the description of emotions. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the interconnection between various aspects of lexical production in narrative discourse and ToM, in order to better understand how these crucial abilities interact. Specifically, the aims of this study are to investigate productivity skills, the expression of subjectivity, the spontaneous tendency to describe emotions in narrative production, and ToM skill across healthy aging. Moreover, building on previous research suggesting a relationship, though not a complete overlap, between pragmatic skills and ToM abilities25,26, we also examined the associations between narrative features (i.e., productivity, the use of subjectivity markers, and emotion description) and ToM performance. This led us to formulate the following research areas and corresponding hypotheses.

First (Research Area 1, RA1), we investigated whether productivity measures (i.e., total number of words, speech rate, and % lexical informativeness), subjectivity markers (i.e., modalizers, affective, evaluative axiological and non-axiological adjectives and adverbs, and first-person singular pronouns), and emotion descriptors (i.e., adjectives and adverbs used to describe the emotions and feelings of characters depicted in the narrative) decline with healthy aging during a discourse production task. We also controlled for the potential influence of participants’ level of formal education. If such a decline is observed, we further examined whether it affects subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors similarly or differentially. Given previous findings showing a general decrease in narrative efficiency after the age of 751,3, along with increasing difficulties in emotion expression during discourse production, we hypothesized that aging would affect productivity levels (Hypothesis 1a). Specifically, we expected no age-related differences in the total number of words produced but anticipated age-related effects on speech rate and lexical informativeness. We also expected that aging would negatively impact the use of subjectivity markers (Hypothesis 1b). For example, we hypothesized that the use of first-person singular pronouns would increase with age, potentially reflecting a greater tendency among older individuals to introduce self-referential intrusions into their narratives. Finally, we hypothesized that aging would affect the use of emotion descriptors (Hypothesis 1c).

Secondly (Research Area 2, RA2), we aimed to assess whether aging also affects performance on tasks measuring the cognitive and affective components of Theory of Mind (RA2a). In line with previous findings, we hypothesized that these tasks would be negatively impacted by healthy aging (Hypothesis 2a). We further examined the potential relationship between those aspects of lexical productivity, subjectivity markers, emotion descriptors, and ToM skills that were found to decline with age (RA2b). Specifically, we hypothesized that the subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors affected by aging would be positively associated with measures of lexical productivity and ToM performance (Hypothesis 2b).

Results

Analysis of productivity levels on the discourse production task

Means and standard deviations for the three groups’ productivity levels are presented in Table 1. Linear regression analyses revealed significant models for all three measures. For total number of words, the model accounted for 10.3% of the variance (F(2, 88) = 4.930, p < 0.009; R2 = 0.103). Only level of formal education was a significant predictor (β = 4.340; p < 0.005; part correlation coefficient: 0.293) uniquely explaining 8.6% of the variance. For speech rate, the model explained 9.2% of the variance (F(2, 88) = 4.336, p < 0.016; R2 = 0.092). Only age was a significant predictor (β = 0.325; p < 0.004; part correlation coefficient: − 0.303), accounting for 9.2% of the variance. For % Lexical informativeness, the model accounted for 6.8% of the variance (F(2, 88) = 3.152, p < 0.048; R2 = 0.068). Only age was significantly associated with this variable (β = − 0.110; p < 0.019; part correlation coefficient: − 0.248), explaining 6.2% of the variance.

To further explore age-groups differences in speech rate and % lexical informativeness, two ANOVAs were conducted with Group (YA vs. OA vs. SOA) as the independent variable, and the two narrative measures as dependent variables. A significant group effect was found for speech rate (F (2, 87) = 4.148, p < 0.019; partial η2 = 0.087) (see also Fig. 1), with a significant linear trend (p < 0.007). Tukey’s post hoc analysis revealed that the YA group spoke significantly faster than the SOA group (< 0.018) but did not differ significantly from the OA group (p = 0.107); no significant difference was found between the OA and SOA groups (p = 0.746). Similarly, a significant group-related difference was observed for % of Lexical Informativeness (F (2, 87) = 5.030, p < 0.009; partial η2 = 0.104) (see Fig. 2), with a linear trend (p < 0.003). Tukey’s post hoc comparisons showed that the YA group scored significantly higher than the SOA group (p < 0.008), while no significant differences were found between the YA and OA groups (p = 0.667) nor between the OA and SOA groups (p = 0.074).

Assessment of subjectivity markers

Means and standard deviations of the analysis of subjectivity markers across the three groups are presented in Table 2. Linear regression analyses revealed no significant models for the following variables: % evaluative non-axiological words (F(2, 88) = 0.920, p = 0.403; R2 = 0.021), % evaluative axiological words (F(2, 88) = 1.379, p = 0.257; R2 = 0.031), % affective words (F(2, 88) = 1.090, p = 0.341; R2 = 0.025), and % first-person singular pronouns (F(2, 88) = 0.962, p = 0.386; R2 = 0.022). However, the model predicting % modalizers was significant (F(2, 88) = 9.687, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.184), explaining 18.4% of the variance. Both age and level of formal education were significant predictors (Age: β = 0.008; p < 0.006; part correlation coefficient: 0.274; Formal education: β = 0.062; p < 0.001; part correlation coefficient: 0.400). Age uniquely accounted for 7.5% of the variance in modalizer use, while formal education explained an additional 16%.

To further explore potential group-related differences in the production of modalizers, an ANCOVA was conducted with Group (YA vs. OA vs. SOA) as the independent variable, % modalizers as the dependent variable, and level of formal education as a covariate (see Fig. 3). The analysis revealed a significant age-related difference in the use of modalizers (F (2, 85) = 4.112, p < 0.020; partial η2 = 0.088), with a significant linear trend (p < 0.008). Tukey’s post hoc comparisons indicated that the YA group used significantly fewer modalizers than the SOA group (p < 0.021), while no significant differences were found between the YA and OA groups (p = 0.078) or between the OA and SOA groups (p = 0.787).

Assessment of emotion descriptors

Means and standard deviations for the analysis of emotion descriptors across the three groups are presented in Table 2. The regression model accounted for 12.2% of the variance in % emotion descriptors (F(2, 88) = 5.983, p < 0.004; R2 = 0.122). Age (but not level of formal education) was significantly associated with this variable (Age: β = − 0.007; p < 0.007; part correlation coefficient: -0.280; Formal education: β = 0.016; p = 0.284; part correlation coefficient: 0.109). Thus, age uniquely explained 7.8% of the variance in % emotion descriptors.

An ANOVA revealed a significant age-related difference in the use of emotion descriptors (F (2, 87) = 4.580, p < 0.013; partial η2 = 0.095), with a significant linear trend (p < 0.004). Tukey’s post hoc tests showed that the SOA group produced significantly fewer emotion descriptors than the YA group (p < 0.012), while the OA group did not differ significantly from either the YA group (p = 0.096) or the SOA group (p = 0.680) (and Fig. 4).

Tasks assessing Theory of Mind

Means and standard deviations for the ToM tasks across the three groups are presented in Table 3.

The linear regression predicted 12.2% of the variance in comprehension of the Strange Stories task (F(2, 88) = 5.991, p < 0.004; R2 = 0.122). Only Level of formal education was a significant predictor (β = 0.191; p < 0.001; part correlation coefficient: 0.337), accounting for 11.4% of the variance in task performance.

For the second-order ToM Stories, the model accounted for 29.4% of the variance (F(2, 88) = 17.882, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.294). Both age and level of formal education were significant predictors (Age: β = − 0.011; p < 0.001; part correlation coefficient: − 0.338; Education: β = 0.053; p < 0.002; part correlation coefficient: 0.294). Age uniquely explained 11.4% and education 8.6% of the variance in this task.

For the RMET, the model predicted 33.4% of the variance (F(2, 88) = 21.593, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.334). Again, both age and education were significant predictors (Age: β = − 0.092; p < 0.001; part correlation coefficient: − 0.432; Formal education: β = 0.271; p < 0.012; part correlation coefficient: 0.226). Age uniquely accounted for 18.7%, and formal education for 5.1%.

To further explore potential group-related differences in performance on the second-order ToM and RMET tasks, two ANCOVAs were conducted with Group (YA vs. OA vs. SOA) as the independent variable, scores on the second-order ToM task and the RMET as dependent variables, and level of formal education as a covariate (see Figs. 5 and 6). The analyses revealed significant age-related differences for both tasks (second-order ToM: F (2, 85) = 7.969, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.158; RMET: F (2, 85) = 11.274, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.210). Linear trends were observed for both tasks (second-order ToM: p < 0.001; RMET: p < 0.001). Tukey’s post hoc analyses showed that, for the second-order ToM task, the YA group performed significantly better than the SOA group (p < 0.001), while no significant differences were found between the YA and OA groups (p = 0.063) or between the OA and SOA groups (p = 0.148). For the RMET, the YA group scored significantly higher than both the OA (p < 0.002) and SOA (p < 0.001) groups, whereas no significant difference was observed between the OA and SOA groups (p = 0.376).

Relation between ToM performance and narrative measures

A series of Pearson’s product-moment correlations were conducted to examine potential relationships among the variables that significantly varied with age (i.e., speech rate, % lexical informativeness, % modalizers, % emotion descriptors, RMET, and second-order ToM). The analyses revealed that RMET performance was positively correlated with second-order ToM (r = 0.545; p < 0.001), % lexical informativeness (r = 0.218; p < 0.039), and % emotion descriptors (r = 0.310; p < 0.003). Second-order ToM was also positively correlated with % lexical informativeness (r = 0.222; p < 0.035) and % emotion descriptors (r = 0.231; p < 0.028). Finally, % modalizers was negatively correlated with speech rate (r = -0.271; p = < 010) (see Table 4).

These correlations revealed patterns of association suggesting distinct underlying constructs. Given the potential multidimensionality within both the ToM and narrative domains, we conducted two separate Principal Component Analyses (PCAs): one for ToM measures and one for lexical measures derived from the multilevel procedure of discourse analysis. This dimensionality reduction approach allowed us to extract composite components that more efficiently captured shared variance within each domain.

As a final step, to assess relationships between cognitive and narrative variables, Pearsons’ product-moment correlations were conducted between the components extracted from two PCAs. For the ToM measures, prior to performing PCA, the suitability of data for factor analysis was assessed. The Barlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. The PCA revealed one component with eigenvalues exceeding 1. Inspection of the scree plot showed a clear break after the first component, which was confirmed by parallel analysis. Varimax rotation indicated that the one-component solution explained 77.2% of the total variance. This component loaded positively on both second-order ToM (= 0.879) and RMET (= 0.879), and was interpreted as reflecting overall ToM ability.

The four linguistic measures found to be affected by aging were entered together into the same PCA to explore whether they cluster into distinct latent components reflecting different functional dimensions of discourse, rather than assuming a priori that they are independent. From a theoretical perspective, this choice is motivated by the fact that these measures capture complementary aspects of discourse production: speech rate and lexical informativeness represent indices of overall verbal productivity and the efficiency of information transfer, whereas emotion descriptors and modalizers reflect qualitative aspects of discourse related to the expression of mental states and speaker’s subjectivity. Preliminary analyses showed that Barlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.003), supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. The PCA revealed two components with eigenvalues exceeding 1. Inspection of the scree plot indicated a clear break after the second component, which was confirmed by parallel analysis. To aid in interpretation, Varimax rotation was applied. The two-component solution explained a total of 65.8% of the variance. The first component accounted for 37.2% of the variance and loaded positively on % lexical informativeness (0.778) and % emotion descriptors (0.832). This component, labeled Informative—Emotional Language Association, likely reflects the spontaneous tendency to describe emotions using informative language. The second component accounted for 29.7% of the variance and loaded positively on speech rate (0.753) and negatively on % modalizers (− 0.826). This component (labeled Speech Rate—Modalizers Association) likely reflects the efficiency in producing modalizers during narrative discourse. Importantly, as both components are derived from variables previously shown to decline with age, we interpret them as reflecting discourse abilities that decrease in efficiency with healthy aging. Finally, a Pearson’s product moment correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between the two lexical components and the ToM component. The analysis revealed that the ToM component was significantly correlated with the Informative—Emotional Language Association component (r = 0.261; p < 0.013), but not with the Speech Rate—Modalizers Association component (r = 0.018; p = 0.865) (see Fig. 7).

Figure illustrating the correlations between the three components identified using PCA. It shows also the loadings of each linguistic or ToM measure on each component. Legend: RMET, Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; ToM, Theory of Mind; NS, Not significant. The asterisk (*) shows a significant correlation.

Discussion

This study was designed to address two primary research areas concerning the effects of healthy aging on lexical skills during a discourse production task: First (RA1), we investigated whether productivity levels, the use of subjectivity markers, and emotion descriptors decline with age during narrative production and, if so, to what extent; Second (RA2), we investigated whether cognitive and affective ToM skills decline with age, and whether there is a relationship between those ToM abilities (i.e., second-order ToM and RMET) and the linguistic variables significantly affected by aging (i.e., modalizers, emotion descriptors, speech rate, and % lexical informativeness). Concerning RA1, we hypothesized that aging would negatively affect speech rate and the ability to produce informative words (Hypothesis 1a), subjectivity markers, especially the use of first-person singular pronouns (Hypothesis 1b), and emotion descriptors (Hypothesis 1c). Regarding the second research area we hypothesized that ToM tasks would be negatively impacted by healthy aging (Hypothesis 2a) and that subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors would be positively associated with measures of lexical productivity and ToM skills (Hypothesis 2b).

Regarding productivity skills, and in line with hypothesis 1a and previous studies1,2,3, no age-related differences were found in the total number of words produced. However, the efficiency of lexical production was significantly affected by age, as reflected in reduced speech rates and lower percentages of lexical informativeness2,27. The combination of preserved word production alongside a decline in lexical informativeness supports previous findings suggesting that older adults’ speech tends to be more off-topic compared to that of younger adults. Furthermore, the observation that both speech and lexical informativeness declined linearly across age groups indicates that the efficiency of lexical production deteriorates gradually with age, rather than showing a sudden drop in older adulthood. This pattern highlights the progressive nature of lexical inefficiency as a characteristic of healthy aging.

Hypothesis 1b was only partially confirmed. Contrary to our expectations, modalizers were the only subjectivity markers to show a significant age effect. Indeed, older adults used significantly more such words than younger participants. According to Kerbrat-Orecchioni5, modalizers are words that express the speaker’s evaluation of the degree of certainty or doubt of what is being described. Interestingly, by their very nature, these words convey a personal evaluation about what is being stated without directly contributing to the narrative’s core content. As such, during discourse analysis, modalizers could be classified as informative words (if they were conveying pieces of information that were perceived as relevant to the flow of the story) or fillers, i.e., words not considered informative in the overall flow of discourse. The correlations and PCA revealed the absence of a significant relation between the use of modalizers and the production of informative words, suggesting that the increased production of such words in the oldest group was mostly related to the inclusion of fillers that did not contribute to the construction of the story gist. The increased use of modalizers may reflect a shift in narrative strategy among older adults, possibly indicating a greater tendency to hedge their statements or reduce assertiveness during discourse production.

Other subjectivity markers were not affected by aging, as the production of affective, evaluative axiological and non-axiological adjectives and adverbs did not decline with age, nor did the use of first-person singular pronouns increase. Therefore, the often-reported off-topic verbosity observed in older adults’ discourse1,2,3,28, which is characterized by the inclusion of words that do not fit with the overall coherence of what is being said, is not necessarily linked to an increased use of self-referential language, as marked by first-person pronouns. Although this study is the first to directly examine the effects of aging on these variables, a few previous investigations have addressed related constructs. For example, Markostamou and Coventry29 explored age-related changes in language skills in relation to visuospatial cognition. Their findings revealed a decline in the ability to name both static and dynamic spatial relations, alongside broader difficulties in non-linguistic visuospatial abilities in older adults. In our study, several subjective adjectives and adverbs referring to spatial relationships were classified as evaluative non-axiological words (e.g., The car is not far from the house, where far reflects a subjective spatial judgment). In contrast to findings on spatial prepositions, in our study these subjective spatial markers did not show age-related decline. This raises the question of whether a more fine-grained classification of evaluative non-axiological adjectives and adverbs might reveal different patterns. For example, it remains unclear whether aging affects the ability to produce subjective physical descriptions of people or objects, such as in utterances like The girl is tall or The young boy is falling, where tall and young imply a subjective evaluation. To our knowledge, no studies have directly addressed these aspects. Additionally, it remains an open question whether other word classes marked by subjectivity (e.g., nouns or verbs) might show age-related effects. Future research should therefore explore a broader range of communicative strategies through which subjectivity is expressed in narrative discourse. Such work may reveal whether other types of subjectivity markers, unlike those examined here, are vulnerable to age-related decline.

In line with Hypothesis 1c the ability to describe the emotional states of narrative characters—captured using emotion descriptors—was found to decline with age. Given its crucial role in maintaining social relationships and supporting effective interpersonal communication7,30, considerable research has examined the ability to process and express emotions during discourse. This capacity is closely tied to the ability to understand the emotions of others. A growing body of evidence suggests that the ability to identify emotions, particularly negative ones, declines with age30. This difficulty has been consistently documented across numerous studies and meta-analyses7,31,32,33. For instance, Visser33 employed both a semi-open categorization task and a labeling task to investigate whether the ability to interpret facial emotions varied by task format. The results showed that the ability to interpret the emotions declined in both formats, with older adults showing difficulty in identifying negative emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger. These findings suggest that the difficulties experienced by older adults are not limited to mapping facial features onto emotion labels. Rather, they also involve difficulties in perceiving and interpreting the facial expressions associated with certain emotions. In the present study, we did not distinguish between positive and negative emotions when analyzing emotion descriptors. This represents a limitation and a promising direction for future research on emotion processing during narrative production. Furthermore, the context in which emotions are expressed plays a key role in the correct description of the emotions of the characters portrayed in the story31,33,34. Although our task relied on static visual stimuli (i.e., images used to elicit narratives) rather than dynamic content such as videos, the narrative format likely encouraged participants to draw on contextual cues and infer characters’ emotional states based on the imagined situation. In this respect, out method may approximate real-life emotional reasoning more closely than traditional tasks focused on isolated facial expression labeling.

Considering RA2, we hypothesized that ToM tasks would be negatively impacted by healthy aging (Hypothesis 2a). This hypothesis was only partially confirmed as aging reduced performance on RMET and tasks assessing second-order ToM but not on the Strange Stories task. Overall, these findings align with previous studies suggesting that RMET is an effective task for assessing ToM and that significant difficulties tend to emerge after the age of 70 in both cognitive and affective ToM21,22,23. Interestingly, we did not observe a significant age-related decline on the Strange Stories task, which is considered to assess a relatively basic form of ToM. In contrast, older adults performed significantly worse on the second-order ToM task, supporting the possibility that task complexity modulates age-related decline in cognitive ToM abilities24. Moreover, the group of senior-old participants performed significantly worse than both young and older adults on the RMET, which assesses affective ToM. These findings reinforce the notion that both cognitive and affective components of ToM are vulnerable to age-related decline, particularly when more complex or subtle inferential processes are required.

Finally, the hypothesis that subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors would be positively associated with measures of lexical productivity and ToM skills (Hypothesis 2b) was partially confirmed by our findings. The PCA revealed that the production of modalizers was not associated with ToM skills. Instead, this variable loaded on the same component as speech rate, suggesting that the component reflects the efficiency of producing modalizers during discourse. More importantly, ToM skills were significantly related to the component labeled Informative—Emotional Language Association, which likely reflects the spontaneous tendency to describe emotions using contextually appropriate and informative language. This finding aligns with previous research indicating a close interconnection between emotion processing and ToM abilities35,36,37, and extends this association to the debate about the relationship between ToM and the ability to describe the emotions of characters in storytelling. To the best of our knowledge, most of the existing research on this topic has focused either on young adults or on individuals with neurological disorders or brain injuries. For instance, Lee et al.38, in a study involving 200 healthy individuals aged 15–25, found that ToM partially mediated the relationship between reasoning ability and emotion interpretation, and also predicted the ability to interpret facial expressions of emotions. In a similar study with 150 healthy young adults aged 20–30, Seo et al.39 reported that reasoning by analogy (defined as “the ability to understand rules and build abstractions by integrating relationships based on non-social visual information” [39, p. 837]) and the ability to interpret the emotions depicted in faces independently predicted RMET performance. In their model, emotion understanding partially mediated the relationship between reasoning ability and ToM performance. Kemp et al.35, in a review of the literature, emphasized that age-related declines in social cognition (including ToM) are only partially attributable to general cognitive decline. Instead, these difficulties may stem from changes in specific brain areas critical to ToM processing. Taken together, our findings suggest that future research should further investigate the relationship between ToM and the ability to interpret and describe emotions in healthy older adults within the context of elicited narrative production. Such studies could offer valuable insights into the interplay between these two abilities, especially in relation to cognitive functioning and its neural underpinnings. More broadly, our results are consistent with recent studies suggesting that while ToM and communicative skills are related, they represent partially overlapping but distinct cognitive domains26,40,41.

In conclusion, our research showed that among the various measures of subjectivity expression, only the use of modalizers was significantly affected by healthy aging, with older adults producing more modalizers than younger participants. Additionally, older individuals produced fewer informative words, fewer emotion descriptors, and spoke at slower speech rates. These findings confirm previous observations regarding age-related changes in language productivity, while also offering new insights into a relatively unexplored area: how aging influences the ability to express subjectivity and describe emotions during storytelling. Furthermore, our results provide valuable information on the relationship between ToM, emotion description, and the ability to produce informative narratives. Our study, however, is not without limitations. Given the limited size of our convenience sample, further research involving larger and more representative populations is needed to confirm and generalize these findings. In addition, future studies should incorporate a broader range of tools for assessing communicative and narrative abilities to strengthen the external validity to the results of the present results. This includes the need to examine lexical markers related to cognitive content, as well as to conduct longitudinal studies to observe developmental trajectories over time. Furthermore, the study’s cross-sectional design does not allow firm conclusions about how the variables under investigation develop across adulthood. To better capture actual age-related trajectories, future studies should employ longitudinal designs. Finally, because participants’ age is inherently confounded with their birth cohort, the observed group differences may reflect not only age-related changes but also cohort-related influences, such as differences in education, cultural experiences, and historical context.

Several avenues for future research have also emerged from our findings. These include exploring other subjectively marked parts of speech (e.g., nouns and verbs), implementing a more fine-grained subclassification of evaluative non-axiological adjectives and adverbs, and distinguishing between the use of positive and negative emotion descriptors. Despite its limitations, our study introduces a novel perspective on the assessment of narrative production in healthy aging by examining subjectivity markers and contributing to the growing body of research on emotion description. Notably, participants were not explicitly instructed to express personal evaluations, judgements, or emotions, nor were they asked to identify the emotional states of the characters. Instead, they were simply asked to tell a story based on visual stimuli. The number of subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors was subsequently assessed through our analysis. This approach raises the possibility that our method may offer a more ecologically valid way of assessing subjectivity expression and emotion description, as participants were not consciously focusing on these elements but rather on constructing a coherent narrative. Future studies should continue to examine the link between emotion description and ToM skill to further clarify the cognitive mechanisms underlying these communicative abilities in healthy aging.

Methods

Participants

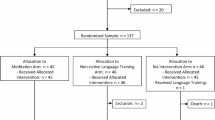

In this study, 90 healthy Italian native speakers were divided into three age groups balanced for gender (see Table 5): 30 young adults (YA: 14 females) aged 20–40 years; 30 older adults (OA: 16 females) aged 65–74 years; and 30 senior older adults (SOA: 15 females) aged 75–86 years. The groups differed significantly in their level of education (F (2, 86) = 5.474, p < 0.006; partial η2 = 0.113). Tukey’s post-hoc analyses revealed that the SOA group had significantly fewer years of education than the YA group (p < 0.004), while the other pairwise comparisons were not significant (see Table 5). The three groups did not differ in gender distribution [X2 (2, N = 90) = 0.267, p = 0.875, Cramérs V = 0.054].

Participants were primarily recruited through local associations and clubs, cultural events, Universities of the Third Age, personal contacts, and advertising on social networks. Participation was voluntary, an no financial compensation was provided.

Exclusion criteria included a history of past or current neurological or neuropsychiatric disorders, brain lesions, severe hearing or vision impairments, substance or alcohol abuse, and the use of mood stabilizers. Regarding cognitive assessment, inclusion required performance within the normal range on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)42, the short form of the Token Test43, and the Naming subtest of the Aachener Aphasie Test44.

The study was approved by the Bio-Ethical Committee of the University of Turin (Protocol 202,174). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their involvement. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials

This study is part of a larger investigation focusing on the effects of aging on cognitive and communicative skills. For the specific purposes of this study, we focused on participants’ discourse production (in terms of productivity, use of subjectivity markers, and emotion descriptors) and ToM (RMET, Strange Stories, and Second-order ToM) skills. These tasks and measures will be described in this section.

Assessment of narrative discourse production

Administration procedures

Narrative assessment was conducted by eliciting spontaneous speech samples using one single-picture scene (i.e., the “Picnic” from45) and two cartoon-picture sequences (i.e., the “Flowerpot” story by Huber and Gleber46, and the “Quarrel” story by Nicholas and Brookshire47). The task was administered individually to each participant in a quiet room under the supervision of a trained researcher, who provided instructions prior to the start. The pictures were displayed on a laptop and remained visible throughout the task to minimize memory demands.

Participants were instructed to avoid using vague deictic expressions such as there, this, here, etc. and were told that the researcher did not know what the images depicted. All narratives were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by two of the authors (A.M. and E.G.) using a multilevel discourse analysis approach48.

Procedures of discourse analysis

The narrative analysis focused on three key aspects of discourse production: productivity, subjectivity markers, and emotion descriptors.

Analysis of productivity levels

Productivity was assessed based on the total number of phonologically well-formed words produced during each story description, as well as the speaker’s efficiency in lexical production. Lexical efficiency was measured using two indices: speech rate (i.e., words per minute) and % of lexical informativeness. The latter was calculated by dividing the number of informative words in the narrative sample by the total number of words and multiplying this result by 100. Words were considered informative if they were phonologically well-formed, semantically and morphologically accurate, and not classified as repetitions, fillers, tangential or ambiguous. The percentage of lexical informativeness is a key indicator of a speaker’s narrative efficiency49.

Analysis of subjectivity markers

The analysis of subjectivity markers followed the categorization proposed by Kerbrat-Orecchioni5. In each discourse sample, the scoring procedure focused on counting occurrences of modalizers, affective, evaluative axiological and non-axiological adjectives and adverbs, and first-person singular pronouns. The analysis of emotion descriptors focused instead on adjectives and adverbs that reflected what the depicted character was presumably feeling or experiencing. Specifically, modalizers were defined as adjectives and adverbs that conveyed the speaker’s evaluation of the degree of certainty or doubt regarding what was being said. For example, in “probably they are fighting because he doesn’t do anything at home”, the adverb probably was scored as a modalizer. A % of modalizers was calculated by dividing the number of modalizers by the total number of words and multiplying by 100. Affective words included adjectives and adverbs reflecting the speaker’s emotional response to the narrative content. For example, in “the poor man is hit by a flowerpot falling from the balcony” the adjective poor was scored as an affective word. A % of affective words was calculated by dividing the number of affective adverbs and adjectives by total words, multiplied by 100. Evaluative non-axiological words referred to subjective evaluations without any positive or negative connotation, or emotional component. For instance, in “the tree is close to the house”, the adjective close was scored as an evaluative non-axiological word. A % of evaluative non-axiological adjectives and adverbs to words was calculated by dividing the number of these words by the total number of words, multiplied by 100. Evaluative axiological words conveyed positive or negative value judgements regarding what was being said. For example, in “the lady was kind with the dog”, the adjective kind was scored as an evaluative axiological word. A % of evaluative axiological adjectives and adverbs was calculated by dividing the number of these words by the total number of words and multiplying by 100. First-person singular pronouns referring to the speaker (e.g., I, me, my) were also counted as markers of subjectivity, as their use reflects the speaker’s presence in the narrative. For example, in “I see a couple having a picnic on the shore”, the pronoun I embeds the speaker into the utterance, as opposed to a more impersonal structure like “There is a couple…”. The % of first-person singular pronouns was calculated by dividing the number of these words by the total number of words, multiplied by 100.

Analysis of emotion descriptors

The analysis of emotion descriptors focused on adjectives and adverbs used by the speaker to describe emotions and feelings of the characters depicted in the narrative. For example, in the utterance “the dog looks happy” the adjective happy was scored as an emotion descriptor. The % of emotion descriptors was calculated by dividing the number of such words by the total number of words in the narrative and multiplying this result by 100.

Considering the distinction between affective words and emotion descriptors, even if a marge of error should always be considered when interpreting other people’s speech samples, the context of the storytelling usually helps to correctly understand if the adjective or adverb the speaker is using refers to their own emotional reactions or to the emotions presumably felt by the depicted character. Importantly, subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors could appear in different contexts within the narrative: they could be informative words (e.g., it’s a beautiful sunny day or the couple is sitting close to a tree), lexical fillers or personal comments (e.g., the same thing happened to me too or what a beautiful scene!), or part of tangential utterances. However, any words that had been identified as repetitions, or contained phonological, semantic, or morphological errors were excluded from the scoring.

Assessment of Theory of Mind skills

Theory of Mind was assessed using three tasks. The first was the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET)12,50. In this task, participants are shown 36 photographs depicting only the eye region of different faces. For each item, they are given four adjective options and asked to select the one that best describes the emotion or mental state the person is presumably experiencing. The total score ranges from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating better ability to correctly interpret subtle emotional cues from visual stimuli.

The Strange Stories task18 involves listening to short narratives that require the participant to infer the thoughts, feelings, or intentions of the characters—for example, in scenarios involving white lies or double bluff). After each story, participants answer one or more questions targeting the characters’ mental states. Higher scores reflect greater mentalization abilities and a more accurate understanding of complex social reasoning.

Second-order ToM abilities were assessed using two stories: John and Mary19 and Peter’s Birthday20. These tasks require participants to understand second-order false beliefs, that is, beliefs about another person’s beliefs. Scoring is based on the accuracy of responses to questions such as “What does Mom say to Grandma after she has asked What does Peter think you got him for his birthday?”. Higher scores reflect stronger meta-representational skills and the ability to reason about others’ mental states in a nested structure.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using JASP. To address the first Research Area (whether age and level of formal education affect measures of productivity, subjectivity markers, and emotion descriptors) and the first part of the second Research Area (whether age and level of formal education affect performance on the three tasks assessing ToM—Strange Stories, second-order ToM, and RMET), a series of preliminary multiple linear regression analyses were performed. Age and level of formal education were entered as predictors, with each linguistic or ToM measure as dependent variables. For variables in which only age emerged as a significant predictor, group-related differences were further explored using one-way ANOVAs, with Group (young adults [YA], older adults [OA], and senior older adults [SOA]) as the independent variable and the relevant measure as the dependent variable. For variables where both age and level of formal education were significant predictors, ANCOVAs were conducted with Group (YA. OA, SOA) as the independent variable, the relevant measure as the dependent variable, and level of formal education as covariate. Effect sizes for both ANOVAs and ANCOVAs were reported using partial eta squared. We applied the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control for false discovery rate at q = 0.0551.

To address the second part of the second Research Area (if there is a relationship between those linguistic and ToM variables that were significantly affected by aging) a series of Person’s product-moment correlations were conducted. These correlations revealed patterns of association suggestive of distinct underlying constructs. Therefore, two Principal Component Analyses (PCAs) were conducted to reduce dimensionality and identify composite components that more effectively captured the shared variance across ToM and linguistic measures, respectively.

Sample size estimation

As we did not have access to the necessary data to estimate effect sizes for several original measures employed in this study (e.g., subjectivity markers and emotion descriptors), we were unable to conduct an a priori power analysis. Therefore, our sample size rationale was based on established methodological recommendations to ensure a minimum sample size for reliable results. Specifically, for the multiple linear regression analyses, we followed the recommendations by52, who suggests that a minimum of 15 participants per predictor are required for a reliable equation. Even when applying the more conservative criterion proposed by53, who recommends the formula N > 50 + 8 m (where m is the number of independent variables), the minimum required sample size would be 66. Since we had the opportunity to recruit 90 participants, we decided to include all of them in the analyses to increase the robustness and statistical power of the study. To address this, we calculated an a-posteriori power analysis using G*Power. Cohen’s f2 values for the variables entered in the regression analyses were calculated and the mean effect size was derived. Considering two predictors, a final sample of 90 participants, and an alpha level of p < 0.05, the achieved power was estimated at 1–β = 0.98.

For the other research areas, we conducted Pearsons’ product-moment correlations and two PCAs. Following the recommendation by54, a subject-to-variable ratio of 10:1 is considered adequate to ensure sufficient power for PCA. Given that our sample included 90 participants, the sample size was well above the threshold for both analyses: the PCA on ToM measures included 2 variables, and the PCA on linguistic measures included 4 variables. Thus, the sample size requirements were met and even exceeded for both PCAs.

Interrater reliability

The scoring procedures were performed by two expert raters (EG and AM). They were blind with respect to the specific age-group of the speakers and preliminarily analyzed 30 stories (3 stories per 10 subjects). An interrater reliability analysis using Kappa statistic was performed. Interrater reliability scores for the two raters were perfect for Words (Kappa = 1.0), Speech rate (Kappa = 1.0), % Evaluative axiological words (Kappa = 1.0), % Affective words (Kappa = 1.0), % Modalizers (Kappa = 1.0) and % 1st person singular pronouns (Kappa = 1.0) and almost perfect for % Lexical informativeness (Kappa = 0.89), Emotion descriptors (Kappa = 0.89), and % Evaluative non-axiological words (Kappa = 0.88).

Data availability

The JASP file with the analyses is openly available for download at the following view-only OSF link: https://osf.io/z5q9n/?view_only = cf0fada3e5b64fd88ccad1317f2f2c93.

References

Hilviu, D., Parola, A., Bosco, F. M., Marini, A. & Gabbatore, I. Grandpa, tell me a story! Narrative ability in healthy aging and its relationship with cognitive functions and Theory of Mind. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 40, 103–121 (2025).

Juncos-Rabadán, O., Pereiro, A. X. & Rodríguez, M. S. Narrative speech in aging: Quantity, information content, and cohesion. Brain Lang. 95, 423–434 (2005).

Marini, A., Petriglia, F., D’Ortenzio, S., Bosco, F. M. & Gasparotto, G. Unveiling the dynamics of discourse production in healthy aging and its connection to cognitive skills. Discourse Process. 62, 479–501 (2025).

Whitworth, A., Claessen, M., Leitão, S. & Webster, J. Beyond narrative: Is there an implicit structure to the way in which adults organize their discourse?. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 29, 455–481 (2015).

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. L’Énonciation: De La Subjectivité Dans Le Langage 4th edn. (Armand Colin, 1999).

Herman, D. Storytelling and the sciences of mind: Cognitive narratology, discursive psychology, and narratives in face-to-face interaction. Narrative 15, 306–334 (2007).

Ruffman, T., Henry, J. D., Livingstone, V. & Phillips, L. H. A meta-analytic review of emotion recognition and aging: Implications for neuropsychological models of aging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 863–881 (2008).

Isaacowitz, D. M. et al. Age differences in recognition of emotion in lexical stimuli and facial expressions. Psychol. Aging. 22, 147–159 (2007).

Rothermich, K., Giorio, C., Falkins, S., Leonard, L. & Roberts, A. Nonliteral language processing across the lifespan. Acta Psychol. 212, 103213 (2021).

Premack, D. & Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a Theory Of Mind?. Behav. Brain Sci. 1, 515–526 (1978).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. & Aharon-Peretz, J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective Theory Of Mind: A lesion study. Neuropsychologia 45, 3054–3067 (2007).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The, “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 42, 241–251 (2001).

Oakley, B. F. M., Brewer, R., Bird, G. & Catmur, C. Theory of mind is not theory of emotion: A cautionary note on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 125, 818–823 (2016).

Pavlova, M. A. & Sokolov, A. A. Reading language of the eyes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 140, 104755 (2022).

Raimo, S. et al. Cognitive and affective Theory of Mind across adulthood. Brain Sci. 12, 899 (2022).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Harari, H., Aharon-Peretz, J. & Levkovitz, Y. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in affective Theory Of Mind deficits in criminal offenders with psychopathic tendencies. Cortex 46, 668–677 (2010).

Baron-Cohen, S. et al. The Reading The Mind In The Eyes Test: Complete absence of typical sex difference in ~400 men and women with autism. PLoS ONE 10, e0136521 (2015).

Happé, F. G. E. An advanced test of Theory Of Mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 24, 129–154 (1994).

Wimmer, H. & Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13, 103–128 (1983).

Sullivan, K., Zaitchik, D. & Tager-Flusberg, H. Preschoolers can attribute second-order beliefs. Dev. Psychol. 30, 395–402 (1994).

Duval, C., Piolino, P., Bejanin, A., Eustache, F. & Desgranges, B. Age effects on different components of Theory Of Mind. Conscious Cogn. S20, 627–642 (2011).

Hilviu, D., Gabbatore, I., Parola, A. & Bosco, F. M. A cross-sectional study to assess pragmatic strengths and weaknesses in healthy ageing. BMC Geriatr. 22, 699 (2022).

Fischer, A. L., O’Rourke, N. & Loken Thornton, W. Age differences in cognitive and affective Theory of Mind: Concurrent contributions of neurocognitive performance, sex, and pulse pressure. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 72, 71–81 (2017).

Ruitenberg, M. F. L., Santens, P. & Notebaert, W. Cognitive and affective Theory of Mind in healthy aging. Exp. Aging Res. 46, 382–395 (2020).

Bischetti, L., Ceccato, I., Lecce, S., Cavallini, E. & Bambini, V. Pragmatics and Theory Of Mind in older adults’ humor comprehension. Curr. Psychol. 42, 16191–16207 (2023).

Bosco, F. M., Tirassa, M. & Gabbatore, I. Why pragmatics and Theory of Mind do not (completely) overlap. Front Psychol. 9, 1453 (2018).

Pistono, A. et al. Inter-individual variability in discourse informativeness in elderly populations. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 31, 391–408 (2017).

Marini, A., Boewe, A., Caltagirone, C. & Carlomagno, S. Age-related differences in the production of textual descriptions. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 34, 439–463 (2005).

Markostamou, I. & Coventry, K. R. Naming spatial relations across the adult lifespan: At the crossroads of language and perception. Neuropsychology 36, 216–230 (2022).

Guerrini, S., Hunter, E. M., Papagno, C. & MacPherson, S. E. Cognitive reserve and emotion recognition in the context of normal aging. Neuropsychol. Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 30, 759–777 (2023).

Isaacowitz, D. M. & Stanley, J. T. Bringing an ecological perspective to the study of aging and recognition of emotional facial expressions: Past, current, and future methods. J. Nonverbal Behav. 35, 261–278 (2011).

Mather, M. & Carstensen, L. L. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychol. Sci. 14, 409–415 (2003).

Visser, M. Emotion recognition and aging. Comparing a labeling task with a categorization task using facial representations. Front Psychol. 11, 139 (2020).

Ochsner, K. N. The social-emotional processing stream: Five core constructs and their translational potential for schizophrenia and beyond. Biol. Psychiatry. 64, 48–61 (2008).

Kemp, J., Després, O., Sellal, F. & Dufour, A. Theory of Mind in normal ageing and neurodegenerative pathologies. Ageing Res. Rev. 11, 199–219 (2012).

Mier, D. et al. The involvement of emotion recognition in affective Theory of Mind. Psychophysiology 47, 1028–1039 (2010).

Mitchell, R. L. & Phillips, L. H. The overlapping relationship between emotion perception and Theory Of Mind. Neuropsychologia 70, 1–10 (2015).

Lee, S. B. et al. Theory of mind as a mediator of reasoning and facial emotion recognition: Findings from 200 healthy people. Psychiatry Investig. 11, 105–111 (2014).

Seo, E. et al. Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test: Relationship with neurocognition and facial emotion recognition in non-clinical youths. Psychiatry Investig. 17, 835–839 (2020).

Domaneschi, F. & Bambini, V. Pragmatic competence. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Skill and Expertise (eds Fridland, E. & Pavese, C.) 419–430 (Routledge, 2020).

Frau, F., Cerami, C., Dodich, A., Bosia, M. & Bambini, V. Weighing the role of social cognition and executive functioning in pragmatics in the schizophrenia spectrum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Lang. 252, 105403 (2024).

Santangelo, G. et al. Normative data for the montreal cognitive assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 36, 585–591 (2015).

De Renzi, A. & Vignolo, L. A. Token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain 85, 665–678 (1962).

Huber, W., Poeck, K., Weniger, D. & Willmes, K. D. AachenerAphasie Test ((AAT) Hogrefe, 1983).

Kertesz, A. Western Aphasia Battery (Grune & Stratton, 1982).

Huber, W. & Gleber, J. Linguistic and non-linguistic processing of narratives in aphasia. Brain Lang. 16, 1–18 (1982).

Nicholas, L. E. & Brookshire, R. H. A system for quantifying the informativeness and efficiency of the connected speech of adults with aphasia. J. Speech Hear. Res. 36, 338–350 (1993).

Marini, A., Andreetta, S., Del Tin, S. & Carlomagno, S. A multi-level approach to the analysis of narrative language in aphasia. Aphasiology 25, 1372–1392 (2011).

Marini, A. & Urgesi, C. Please, get to the point! A cortical correlate of linguistic informativeness. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 2211–2222 (2012).

Vellante, M. et al. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test: Systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry. 18, 326–354 (2013).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: dA practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Stevens, J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences 3rd edn. (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using multivariate statistics 4th edn. (HarperCollins, 2001).

Nunnally, J. O. Psychometric Theory (McGraw-Hill, 1978).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was proofread and edited for language clarity using CHATGPT. All scientific content, interpretations, and conclusions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Funding

This research was supported by PRIN 2022, Prot. n. 2022CZF8KA, project title: “ACTIVe communication: Assessment and enhancement of pragmatic and narrative skills in hEaLthY aging (ACTIVELY)” Avviso pubblico n. 104 del 02/02/2022—PRIN 2022 PNRR M4C2 Inv. 1.1. Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (Financed by EU, NextGenerationEU)–CUP G53D23003110006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EG: conceptualization, test administration, linguistic analyses, original draft preparation; FMB.: funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision of test administration, reviewing and editing; AM: funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision of test administration, analyses, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gallo, E., Bosco, F.M. & Marini, A. An assessment of the relation between narrative productivity, subjectivity expression, emotion description, and ToM abilities in healthy aging. Sci Rep 15, 39837 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23442-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23442-9