Abstract

This paper examines the properties of quasi-periodic photonic crystals to develop biomedical sensors for oral cancer detection, utilizing parity-time symmetry conditions. A photonic crystal structure based on the Thue-Morse sequence utilizing silicon dioxide (SiO2) and silicon (Si) is proposed. This structure comprises a defect layer containing healthy or cancerous cell samples inserted in the center between two identical Thue-Morse structures. The main objective is to analyze the transmittance spectra of the proposed system using the transfer matrix method with MATLAB simulation. The effects of various parameters, including period number, defect thickness, and the refractive index of the silicon dioxide complex, were analyzed to optimize sensor sensitivity. Due to the high absorption properties of normal and cancerous cells, the associated confined resonant mode exhibits very low transmittance. To solve this problem, a parity-time symmetry optimization technique was employed in the Terahertz band to selectively amplify the resonant mode. The results show that the gain/loss factor is a critical parameter for amplifying the resonance mode transmittance within the photonic band gap. The optimized sensor exhibited a remarkable resonance peak magnification, achieving a transmittance of 3.16 × 109% with an extremely high sensitivity of 9.0 × 109%/RIU for cancer cell detection. These results demonstrate that the proposed quasi-periodic structure with Parity-time symmetry enables sensitive distinction of pathological tissues, primarily due to its resonant spectral response. This underlines its potential application in the precise optical detection of oral cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One-dimensional photonic crystals (1D-PCs) are layered structures composed of materials with contrasting refractive indices (RIs) arranged in a spatially periodic pattern1,2,3,4. This periodicity generates a multiple-interference phenomenon, thanks to the Bragg scattering mechanism between the light waves reflected at the interfaces5,6. This phenomenon gives rise to photonic band gaps (PBGs) in which no electromagnetic (EM) wave propagation can occur in specific frequency ranges7,8,9. This spectral filtering depends on RI contrasts, layer thickness, and structural symmetry. For example, Tammam et al. studied a defective 1D-PC in GaN and porous GaN, showing high sensitivity to sample RI variation, with a resonance peak shift exploited to detect malaria with a high figure of merit (FoM)10. While sensitivity indicates how much the signal moves, it does not account for how sharp and distinguishable the resonance peak is. A high sensitivity is less valuable if the resonance peak is very broad. Therefore, the FOM is used to characterize the overall detection accuracy by incorporating the linewidth of the resonance. It is defined as the sensitivity divided by the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the resonance peak. When a defect is introduced into a PC, with a change in thickness or an RI, the structure behaves like a resonant cavity, capable of maintaining a confined mode in the PBG, which manifests itself as tightly confined resonant peaks11,12. This defect mode is particularly sensitive as it results from a local imbalance in optical impedance, making it a powerful tool for detecting minute variations in RI properties used in biosensing applications13,14,15,16.

As an alternative to perfectly periodic structures, photonic quasi-crystals, such as Thue-Morse, Rudin-Shapiro, Cantor, and Fibonacci sequences, are an increasingly important object in electromagnetic (EM) wave filtering, adapted by mathematically well-determined non-periodic arrangements17,18,19,20,21. These arrangements disrupt the classical periodic spectrum, generating more PBGs and numerous localized modes22. Zaky et al. have studied a photonic structure based on a Cantor sequence in doped porous silicon, demonstrating its ability to detect gamma radiation by means of resonance peak tuning in the PBG with high sensitivity and excellent spectral stability23. In particular, Thue-Morse structures can finely target specific frequencies and localize light energy in particular regions, which is particularly useful in sensitive devices such as sensors24 and optical filters25,26,27.

Biomedical detection using optical structures has also become increasingly interesting in recent years, particularly for cancer sensors28,29,30,31,32, thanks to the high sensitivity and ease of design of these layered systems. For example, Vaijayanthimala et al. applied a MgO-SiO2 photonic crystal as a sensor for diseased blood samples. They improved the detection performance of this sensor by examining optimization parameters such as sensitivity, Q-factor, FoM, and LoD33. Khedr et al. studied a defective photonic crystal for the detection of cancerous blood, achieving a sensitivity of 244.4 \(\:nm/RIU\) and a quality factor of 9138 at normal incidence. This sensitivity was increased to 344 \(\:nm/RIU\) at an optimized incidence angle of 60°, with resonance peak adjustment as a function of sample RI34. Nayan et al. have proposed a 1D-PC GaAs/MgF₂ biosensor with a central defect, achieving a sensitivity of 2564.83 \(\:nm/RIU\), a quality factor of 2979.317, and a FoM of 3612.175 \(\:{RIU}^{-1}\), for precise spectral detection of cancer cells35. Recent progress in WaveFlex biosensors has demonstrated remarkable sensitivity and versatility through novel fiber geometries and hybrid nanomaterial coatings. For instance, chitosan-coated Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles combined with WS₂ quantum dots enabled highly sensitive detection of Staphylococcus aureus with a limit of detection (LoD) of ~ 6.67 CFU/mL36. Similarly, multi-core fiber probes integrated with WS₂ and C₃N quantum dots have been utilized for xanthine sensing, exhibiting excellent performance37.

In conventional photonic structures, the absence of an EM amplification mechanism limits transmittance to values below or equal to 100%, which restricts detection accuracy38,39,40,41. To address this limitation, incorporating parity-time (PT) symmetry serves as a key optimization strategy that enhances resonant modes and significantly boosts sensor sensitivity42. When applied to photonic crystal (PC) structures with complex refractive index layers, PT symmetry amplifies localized modes within defect-containing cavities by precisely balancing gain and loss effects. Gain and loss layers can be generated by doping with quantum dots using an optical pump43. Recently, numerous studies have exploited the PT symmetry effects in various application fields, particularly in photonic sensors44,45. Zaky et al. analyzed a THz sensor with PT symmetry based on a defective photonic crystal, achieving a sensitivity of 62.6 \(\:GHz/RIU\:\)and a confined peak amplification of 3.8 × 106% at a low propylene glycol concentration43. Zaky et al. proposed a 1D photonic crystal sensor based on PT symmetry for pressure detection, achieving an amplified transmittance of 12029.1%, with a sensitivity of 4.9 nm GPa−1 in position and 1844 %/GPA in amplitude, under 6 GPa pressure46. These structures, based on PT symmetry conditions, offer enhanced spectral sensitivity and selective response, making them promising tools for fast, reliable optical detection.

The proposed structure is composed of quasi-periodically arranged layers of SiO₂ and Si, and features a central defect introduced in the form of blood samples containing healthy or cancerous cells. This defect acts as an optical cavity whose resonance properties are highly dependent on the EM nature of the samples introduced. Using the transfer matrix method (TMM), transmittance spectra were simulated in the THz range, analyzing the influence of various geometric and physical system parameters. Our results show that the gain/loss factor is crucial in determining the perfectly amplified defect mode. At the Q critical value, namely \(\:Q=7.5846\) for healthy cells, an extremely narrow resonance peak is generated in the PBG, with an amplified transmittance of up to 3.36 × 109% and a high sensitivity of 9.5 × 1010%/RIU Similarly, for \(\:Q=5.06691,\) corresponding to cancer cells, the amplified transmittance peak is 3.16 × 109%, with a sensitivity of 9.0 × 109%/RIU. This performance far exceeds that of conventional structures without PT symmetry, confirming the proposed device’s effectiveness for highly sensitive optical detection of cancer cells. The studied structure successfully combines the advantages of quasi-periodicity and magnified localized resonance offering a new high-performance THz sensor for oral cancer detection.

Equations and theory

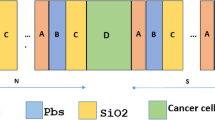

Figure 1a shows a schematic presentation of a 1D photonic crystal (1D-PC) composed of SiO2 (layer \(\:A\)) and Si (layer \(\:B\)) materials arranged quasi-periodically according to the third Thue-Morse sequence. Each layer is characterized by its optical and geometric properties, in particular its RI and thickness. Thue-Morse sequences are generally calculated using the following recursive relationship: \(\:{S}_{n}=\left({S}_{n-1}\right)\left({\stackrel{-}{S}}_{n-1}\right)\), \(\:\forall\:n\ge\:2\) with \(\:{S}_{0}=A\) and\(\:\:{S}_{1}=AB\)47,48,49. Specifically, the third-order Thue-Morse used here was calculated according to the configuration\(\:\:{S}_{3}={S}_{2}{\stackrel{-}{S}}_{2}=ABBABAAB\), with \(\:{S}_{2}=ABBA\). A defect layer (\(\:{d}_{0}\) thick) containing healthy or cancerous cells in the form of blood samples is inserted between two identical Thue-Morse structures. Consequently, as shown in Fig. 1a, the proposed conventional sensor structure is represented by the configuration [Air*(\(\:{S}_{3}\))N *(sample)*(\(\:{S}_{3}\))N *substrate], where \(\:N\:\)is the period number of the \(\:{S}_{3}\) sequence.

We chose Si/SiO₂ because they provide strong refractive index contrast, low THz absorption, biocompatibility, and mature fabrication routes. Importantly, SiO₂ can be doped with polymers or quantum dots to form active gain/loss layers under optical pumping, which makes it highly suitable for realizing PT-symmetric photonic crystal sensors in the THz regime. Gain-loss materials play a central role in the realization of systems with PT symmetry. The introduction of quantum dots into the SiO₂ layer enables the design of distinct active gain and loss regions43,50. Under the effect of external optical pumping, the quantum dots in the gain layer absorb photons at specific frequencies and then re-emit them through stimulated emission43,51. This emission, coherent with the resonant modes’ frequency, favors efficient coupling, leading to significant amplification of the resonance peak. Under the PT symmetry conditions applied to the SiO2 layer, the sensor schematic is illustrated in Fig. 1b.

The experimental data from reference52 were fitted using the following RI (\(\:n\)) and absorption amplitude (α) equations, which describe the response of healthy and cancerous oral cells across the frequency range of 0.20 THz to 0.91 THz at 20 °C.

For normal cells:

For cancerous cells:

In the oral cancer detection context, using a quasi-periodic PC with PT symmetry, the complex RI of the SiO₂ material was modified to introduce optical loss and gain, respectively, symmetrically, according to the following Eqs. (5) and (6):

where \(\:{n}_{R}\)=2.1 represents the real RI of SiO₂, while the imaginary term \(\:\pm\:\:i\:0.01\:Q\:\)reflects a complex adjustment to simulate light amplification (gain) or attenuation (loss) effects in SiO₂ layers. \(\:Q\) is a factor used to control the optical gain or loss intensity in the SiO₂ layer.

The incident EM wave propagation through the proposed structure is studied with precision by applying the TMM using MATLAB software at room temperature (20 °C)7,45,46. The TMM is chosen for its computational efficiency and accuracy in modeling the interaction of electromagnetic waves with multi-layered structures. The core of this approach is formulating a transfer matrix for each homogeneous layer, which encapsulates its unique dielectric properties (refractive index n) and geometry (thickness d). Thus, the whole system matrix is calculated as follows:

where \(\:{T}_{11}\), \(\:{T}_{12}\), \(\:{T}_{21}\), and \(\:{T}_{22}\) are the total system transfer matrix (TM) elements. \(\:{T}_{A}\), \(\:{T}_{B}\), and \(\:{T}_{Sample}\:\)are the TMs of the SiO2, Si, and defect layers containing the healthy or cancer cell samples.

The transfer matrix (TM) for each layer is:

where \(\:{\beta}_{i}\) represents the phase variation based on RI (\(\:{n}_{i}\)), incidence angle (\(\:{\theta}_{i}\)), and thickness for each layer i as follows:

where \(\:i=A,\) \(\:B\) and \(\:sample\) (D) and \(\:k=\frac{2\pi\:}{\lambda\:}\:\)is the EM wave vector.

For a transvers electric (TE) polarized wave, \(\:{P}_{i}\) is expressed by33:

Applying Descartes’ Snell’s law35,53, the angles of incidence are determined as follows:

The total transmittance rate through the defective Thue-Morse structure is calculated as follows30:

with,

where, \(\:{P}_{air}\) and \(\:{P}_{substrate}\:\)represent the incident medium (air) and the substrate, respectively.

Results and discussions

This section analyzes the EM wave propagation within the proposed quasi-periodic structure with PT symmetry, integrating healthy or cancerous cells as a central defect. The numerical results, obtained using MATLAB, focus mainly on the system’s transmittance properties as a function of terahertz frequency. Here, the thickness and RI of layer \(\:A\) (SiO2) are \(\:{d}_{A}=\)130 \(\:\mu m\) and \(\:{n}_{A}=\)2.1, respectively, while layer \(\:B\) (Si) has a thickness and RI of \(\:{d}_{B}=\)70 \(\:\mu m\) and \(\:{n}_{B}=\)3.4, respectively. The period number of the quasi-periodic structure and the defect layer thickness were initially chosen at \(\:N=2,\) and \(\:{d}_{0}=40\:\mu m.\)

Figure 2 shows the significant influence of inserted defects, including healthy and cancerous cells, on the transmittance spectrum (\(\:T\)) of a conventional Thue-Morse structure without PT symmetry (Fig. 1a), where \(\:T\le\:1\:\left(100\%\right)\). In the absence of the defect layer (blue line), a PBG appears between 0.347 and 0.392 THz, where EM wave propagation is forbidden in this frequency zone, as shown in Fig. 2. The appearance of this PBG results from the periodicity of the Thue-Morse (\(\:ABBABAAB\))4 structure, with sharply contrasting RIs between the two SiO2 and Si layers. Introducing the central defect of cancerous cells into the structure locally modifies the effective RI due to the specific EM properties of tumor cells, such as greater absorption. This modification strongly disturbs the wave propagation conditions, resulting in a significant transmittance attenuation and creating a significant PBG compared to the without defect structure, as shown by the yellow line in Fig. 2. Moreover, the presence of cancerous and healthy cell defects in the structure has a significant impact on the transmittance spectrum through the creation of a localized resonance peak, which is absent in the perfect configuration (blue line). This resonance is explained by the generation of a defect mode induced by the defective cell, due to a break in the system’s spatial periodicity and increased wave localization in the defect layer. Specifically, the resonance peak filters a transmittance of 15.35% for the defect of cancerous cells, which is higher compared to the defect of healthy cells, which has a low transmittance of 6.03% (red line). This reveals a strong EM energy localization due to impedance differences in the presence of cancerous cells, unveiling a distinctive optical behavior that is exploitable for early detection of abnormal tissue. These results confirm the sensitivity of the proposed structure to the presence of cancerous or healthy cells, paving the way for the development of selective optical diagnostic devices in the Terahertz frequency range.

To improve the proposed biomedical sensor’s performance, the impact of various quasi-periodic PC geometrical parameters is analyzed in the following section to identify the optimal sensor parameters. These parameters are both the period number (\(N\)), and the defect layer thickness (\({d}_{0}\)).

First, Fig. 3a–f shows the transmittance variation as a function for frequency of the conventional Thue-Morse structure in healthy cells at different \(\:N\) values. The aim is to examine the PBG and resonance peak behavior by varying the \(\:N\) value from 1 to 6 periods. Increasing \(\:N\) raises the quasi-periodicity complexity, which reinforces the non-uniform Bragg interference phenomenon and leads to the increasingly pronounced and wide PBG due to internal multiple reflections, visible in particular from \(\:N=2\) onwards. This PBG is separated by two pass bands where transmittance is essential, which become narrower and more numerous due to the increase in \(\:N\:\)from 1 to 6 periods, as clearly shown in Fig. 3(a-f). In addition, and specifically for \(\:N=2\) (Fig. 3b), the insertion of healthy cells as a central defect layer disturbs the local structural symmetry, inducing the appearance of a resonance peak with a low transmittance of \(\:6.04\:\%\) at the 0.38 THz frequency position. This resonance peak is located in a wide PBG ranging from 0.34 to 0.40 THz. Physically, at this period (\(\:N=2\)), the structure is less complex, breaking the local periodicity and introducing an RI perturbation into the structure. This perturbation acts as a resonant cavity, i.e., a region capable of locally confining EM waves at a specific frequency within the system’s PBG. As a result, the proposed sensor performs well at \(\:N=2\), which is considered the optimal value for accurately identifying of healthy cells.

The transmittance variation as a function of frequency for the defect of cancerous cells at different period numbers \(\:N\) is shown in Fig. 4 a–f. As shown in Fig. 4a for \(\:N=1\), the defective structure configuration is inadequate to distinctly reveal PBG properties and the resonance peak. By increasing the period number \(\:N\), the constructive interference due to Bragg scattering is reinforced, resulting in more pronounced PBG formation. This structural improvement leads to more efficient wave reflection and more selective zero-transmittance filtering. In contrast, for \(\:N=2\) (Fig. 4b), the interaction between the cancerous cells introduced as a defect layer and the two Thue-Morse structures induces the appearance of a narrow defect mode with a \(\:15.35\:\%\) transmittance located at 0.38 THz within a broad PBG. Importantly, the transmittance of this resonance peak is higher than that created in healthy cells (Fig. 3b) in the same period, reinforcing the cancerous cells’ influence on the intensity of the resonance mode transmittance. Consequently, the PBG and transmittance peak properties in this case confirm that \(\:N=2\) is the optimal sensor parameter, guaranteeing efficient wave filtering. These results demonstrate the enhanced performance of the proposed sensor for both sensitive and selective detection of cancerous cells.

Figures 5a–f and 6a–f show the transmittance variation as a function of frequency for healthy and cancerous cells, respectively, at different defect layer thickness values \(\:{d}_{0}\). The results show that varying \(\:{d}_{0}\) has a direct impact on PBG behavior and the appearance of the resonance peak for both healthy and cancerous cells. In either case, increasing \(\:{d}_{0}\) results in a gradual shift of the resonance peak towards lower frequencies (red shift). This behavior is characteristic of an optical cavity with an increased effective length. Precisely for healthy cells, the optimum thickness lies in the \(\:{d}_{0}=40\:\mu m\) value (Fig. 5c), for which we observe both a complete PBG and good wave confinement through the formation of a narrow resonance peak located at 0.38 THz for a transmittance of \(\:5.91\:\%\). For cancerous cells, the resonance peak becomes narrower and more intense, with a \(\:15.34\:\%\) transmittance, also at \(\:{d}_{0}=40\:\mu m\) (Fig. 6c), indicating a sufficiently completed PBG. Then, for \(\:{d}_{0}\) greater than \(\:40\:\mu m\), the resonance peak appears with a very low transmittance that almost disappears inside the PBG. Thus, the optimum value of \(\:{d}_{0}\) for obtaining a complete PBG and an exploitable resonance simultaneously is \(\:{d}_{0}=40\:\mu m\) in both cases, constituting an optimal condition for spectral detection of defects, particularly in blood samples from healthy or cancerous cells.

Transmittance variation as a function of frequency (THz) of the conventional structure proposed for healthy cells at different defect layer thicknesses \(\:{d}_{0}\). (a) \(\:{d}_{0}=20\) µm, (b) \(\:{d}_{0}=30\) µm, (c) \(\:{d}_{0}=40\) µm, (d) \(\:{d}_{0}=50\) µm, (e) \(\:{d}_{0}=60\) µm, and (f) \(\:{d}_{0}=70\) µm.

Transmittance variation as a function of frequency (THz) of the conventional structure proposed for cancerous cells at different defect layer thicknesses \(\:{d}_{0}\). (a) \(\:{d}_{0}=20\) µm, (b) \(\:{d}_{0}=30\) µm, (c) \(\:{d}_{0}=40\) µm, (d) \(\:{d}_{0}=50\) µm, (e) \(\:{d}_{0}=60\) µm, and (f) \(\:{d}_{0}=70\) µm.

In the context of oral cancer detection using a Thue-Morse structure-based PC, the next section of this work will focus on an in-depth analysis of material property effects on localized resonant mode behavior using PT symmetry conditions. More specifically, the complex RI impact of the SiO2 layer possessing PT symmetry was studied as a function of the gain/loss factor \(\:Q\), based on Eqs. (5) and (6). This factor is directly related to the quantity of EM energy absorbed or amplified in the structure, making it possible to simulate the optical impact of these samples, such as cancerous cells in the PC. The primary objective is to leverage the physical properties associated with PT symmetry to amplify resonant peak transmittance using the optimal parameters previously identified, thereby improving the sensitivity of cancer cell detection.

Figure 7a–l shows the evolution of transmittance spectra for healthy cells in the proposed sensor with PT symmetry as a function of the gain/loss factor \(\:Q\), which varies from 1 to 10. As shown in Fig. 7, it is clear that the PBG behavior is influenced by the PT symmetry conditions due to the change in the complex RI, compared with the results analyzed above the conventional structure. Furthermore, with regard to the sensor’s transmittance properties, we note that for low \(\:Q\) values, between 1 (Fig. 7a) and 3 (Fig. 7c), the transmittance peaks are broad, reflecting weak resonance with transmittance intensities ranging from \(\:7.52\) to \(\:90.17\:\%\). Indeed, at lower \(\:Q\:\)factors, the gain and loss are insufficient to trigger amplified interference or reach critical modes. In this case, the system behaves almost like a conventional photonic crystal. As \(\:Q\) increases, these peaks become narrower, and their amplitude rises sharply, indicating an increased energy concentration around a specific frequency of 0.39 THz. This behavior is characteristic of the local resonant modes amplified by the progressive addition of a gain/loss factor in the SiO2 layer. A striking feature appears around \(\:Q=7.5846\), where the system reaches perfect resonance, revealing an extremely narrow peak and a more amplified transmittance of 3.36\(\:\times\:{10}^{9}\:\)% as shown in Fig. 7h. Physically, these characteristics result from reaching an exceptional point in the PT’s symmetrical structure, where the gain and loss effects are perfectly balanced. This particular configuration allows maximum localization of light energy and exceptional transmittance. Furthermore, in Fig. 7k and l, corresponding to \(\:Q=9\), \(\:Q=10\), the peak becomes wider, and the transmittance intensity drops considerably to \(\:27.94\:\%\), which mainly explains the degradation of the resonant mode due to a break in PT symmetry. This clearly confirms that the \(\:Q=7.5846\) value is a well-identified critical threshold, where gain and loss are perfectly equilibrated, resulting in a very good amplified peak. These results are useful as a powerful EM transmittance filter, which can be considered a reliable reference for healthy cells.

Transmission spectrum versus frequency of the proposed 1D-PC sensor with PT symmetry for healthy cells, at different gain/loss factors \(\:Q\). (a) \(\:Q=1\), (b) \(\:Q=3\), (c) \(\:Q=6\), (d) \(\:Q=7\), (e) \(\:Q=7.3\), (f) \(\:Q=7.4\), (g) \(\:Q=7.5\), (h) \(\:Q=7.5846\), (i) \(\:Q=7.7\), (j) \(\:Q=8\), (k) \(\:Q=9\), and (l) \(\:Q=10\).

Figure 8 illustrates the variation in the resonance peak width at half-maximum (\(\:FWHM\)) and maximum transmittance (\(\:T\)) as a function of the gain/loss factor \(\:Q\). We observe that the \(\:FWHM\) decreases progressively as Q increases, reaching a pronounced minimum at \(\:Q=7.5846,\) before increasing again. Concurrently, maximum transmittance reaches a significant peak at the same \(\:Q\:\)value, indicating optimal transmission, followed by a rapid fall. This correlation suggests that the system reaches a critical resonance, characterized by maximum transmission (an excellent amplified peak) with a minimum \(\:FWHM\:\)at \(\:Q=7.5846,\) reflecting a highly confined mode. This behavior is due to a balance between gain and loss, achieved through the presence of PT symmetry, which confirms the results shown in Fig. 7h.

The impact of cancerous cells on the resonance peak behavior through the defective Thue-Morse structure with PT symmetry is illustrated in Fig. 9a–l. The latter (Fig. 9a–l) shows the variation of transmittance spectra as a function of frequency for different gain/loss factors \(\:Q\). The aim here is to progressively manipulate the \(\:Q\) value from 1 to 10, in order to identify its critical value, which gives a strongly amplified intensity peak. The results show a low transmittance of \(\:22.38\:\%\)recorded by the system at \(\:Q=1.\) Whereas transmittance increases considerably with the value of \(\:Q\). Q then decreases again. More precisely, as shown in Fig. 9g, the transmittance peak appears narrower and reaches the most amplified (optimum value) value of 3.16 \(\:\times\:{10}^{9}\:\)% at \(\:Q=5.06691\) in the 0.38 THz frequency position. This physical property is essentially due to a radical change in the spectral response and eigenmodes of the structure resulting from PT symmetry conditions, directly influencing the complex RI of doped SiO2. Figure 10 shows the variation in \(\:FWHM\) and transmittance of the resonance peak as a function of different \(\:Q\) values. The maximum transmittance peak corresponds to the minimum \(\:FWHM\:\)at the exceptional value of \(\:Q=5.06691\). The low \(\:FWHM\:\)value indicates a very high resonance peak quality factor, reflecting strong EM energy conservation as an effective transmittance filter at a specific frequency of 0.38 THz. These results clearly show that the proposed sensor can detect cancer cells with high efficiency at the critical \(\:Q\) of \(\:5.06691\), thanks to the amplification mechanism based on PT symmetry.

Transmission spectrum versus frequency of the proposed 1D-PC sensor with PT symmetry for cancerous cells, at different gain/loss factors \(\:Q\). (a) \(\:Q=1\), (b) \(\:Q=3\), (c) \(\:Q=4.5\), (d) \(\:Q=4.8\), (e) \(\:Q=4.9\), (f) \(\:Q=4.95\), (g) \(\:Q=5.06691\), (h) \(\:Q=5.1\), (i) \(\:Q=5.5\), (j) \(\:Q=6\), (k) \(\:Q=8\), and (l) \(\:Q=10\).

Figure 11 shows the variation of transmittance as a function of frequency at the critical value\(\:\:Q=7.5846\:\)for healthy cells (Fig. 11a) and at \(\:Q=5.06691\) for cancerous cells (Fig. 11b), previously analyzed after the application of PT symmetry conditions. Figure 11a, b clearly shows that the maximum transmittance of the amplified peak is only reached at the critical value specific to the \(\:Q\:\)for each cell type, reflecting a spectral sensitivity of the system to the nature of the sample introduced. For example, as shown in Fig. 11b, the cancerous cells transmittance (\(\:Q=5.06691\)) reaches a colossal value of \(\:T=3.16\times\:{10}^{9}\:\%\), much higher than that of healthy cases (38.49%) at the same \(\:Q\) value, highlighting an over-resonance effect caused by the cancerous tissue’s abnormal response at this \(\:Q=5.06691\) value. These results confirm the ability of our system (quasi-periodic PC with PT symmetry) to discriminate pathological tissues extremely sensitively by analyzing the resonant spectral nature, paving the way for more accurate non-invasive optical cancer diagnosis.

The sensitivity is a measure of the system’s response to a change in the target parameter (the refractive index of the cells). We analyze two types of sensitivity: one based on the change in transmitted optical intensity \(\:S\left(T\right)\) and another based on the shift of the resonant frequency \(\:S\left({f}_{R}\right)\). Sensitivity based on transmittance intensity variation is an important index for improving sensor performance and can be determined according to Eq. (14) below. This represents the shift in amplified peak transmittance intensity as the sample RI varies by one unit. Table 1 summarizes the gain/loss parameters \(\:Q\), amplified peak transmittance T and sensitivity\(\:\:S\left(T\right)\:\)of the proposed sensor with PT symmetry for healthy and cancerous cells under optimal conditions. The results clearly demonstrate the proposed sensor’s effectiveness in amplifying the resonance peak and detecting and distinguishing between healthy and cancerous cells with high sensitivity, achieving \(\:9.5\times\:{10}^{10}\) \(\:\%/RIU\) and \(\:9.0\times\:{10}^{9}\) \(\:\%/RIU\), respectively.

In addition, the sensitivity of the frequency variation of the resonance peak per unit RI is calculated by Eq. (15)43. The proposed sensor recorded a significant sensitivity \(\:S\left({f}_{R}\right)\) of 16.3 \(\:GHz/RIU\) at \(\:\text{Q}=7.5846\) and 13.3 \(\:GHz/RIU\) at \(\:\text{Q}=5.06691.\) Table 2 presents a comparative study that clearly demonstrates the greater sensitivity of our sensor compared to previous studies. This confirms the optimal performance of the proposed system as a powerful biomedical sensor and, in particular, a precise cancer sensor.

While the proposed PT-symmetric Thue-Morse sensor demonstrates exceptional theoretical sensitivity, we acknowledge several practical challenges that must be addressed for experimental realization and deployment. The most significant limitation lies in the practical maintenance of the exact PT-symmetric phase. Our simulations assume ideal and stable gain and loss parameters (\(\:{Q}_{\varvec{G}\varvec{a}\varvec{i}\varvec{n}}\) = \(\:{Q}_{\varvec{L}\varvec{o}\varvec{s}\varvec{s}}\)). In an experimental setting, achieving this balance is highly non-trivial. The required optical gain is typically realized using active materials like quantum dots or dyes, which can suffer from non-linear saturation, inherent instability, and thermal degradation over time. Even minor fluctuations in pump laser power or temperature could disrupt the delicate balance needed to operate precisely at the exceptional point, potentially leading to significant performance degradation and unreliable readings.

Furthermore, thermal effects present a dual challenge. First, the pumping mechanism used to achieve gain may generate heat, which can induce thermal lensing, alter refractive indices, and cause mechanical stress within the multilayer structure. This can detune the resonant cavity modes and distort the transmission spectrum. Second, the refractive index of the analyte itself (cells) is temperature-dependent. Therefore, precise temperature control would be an essential requirement for any practical device based on this principle to ensure that observed spectral shifts are due to refractive index changes from biomarkers and not from thermal fluctuations. Finally, the fabrication of the quasi-periodic Thue-Morse structure, while feasible, requires precise nanoscale or micron-scale deposition techniques to ensure layer uniformity and minimize scattering losses at interfaces, which are not accounted for in our ideal model. Despite these hurdles, the outstanding theoretical performance of this design provides a strong motivation to overcome these engineering challenges for next-generation, high-sensitivity diagnostic tools.

Conclusion

In summary, the introduction of a defect layer of healthy or cancerous cells in the form of blood into the center of a quasi-periodic Thue-Morse structure generates resonant modes sensitive to the nature and EM properties of the inserted biological sample. The TMM was used to simulate the proposed sensor’s transmittance using MATLAB software. Parametric analysis has shown that the defect thickness and period number directly control the resonance peak quality and efficiency and the robust photonic band gap formation. By exploiting PT symmetry conditions, thanks to precise gain/loss factor adjustment, exceptional resonant amplification was achieved, reaching a transmittance of 3.16\(\:\times\:{10}^{9}\:\%\:\)and a sensitivity of \(\:9.0\times\:{10}^{9}\:\%/RIU\), thus significantly improving the sensor’s performance for oral cancer detection. These results validate the proposed structure’s effectiveness as an advanced THz sensor for cancer, outperforming conventional designs (without PT symmetry) in terms of spectral sensitivity and cell selectivity.

Data availability

Requests for materials or code should be addressed to Zaky A. Zaky.

References

Abohassan, K. M., Ashour, H. S. & Abadla, M. M. Tunable wide Bandstop and narrow bandpass filters based on one-dimensional ternary photonic crystals comprising defects of silver nanoparticles in water. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 161, 110484 (2022).

Sharifi, M., Rezaei, B., Pashaei Adl, H. & Zakerhamidi, M. S. Tunable Fano resonance in coupled topological one-dimensional photonic crystal heterostructure and defective photonic crystal. Journal Appl. Physics. 133, (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Sallah, M., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Topological edge state resonance as gamma dosimeter using poly nanocomposite in symmetrical periodic structure. Sci. Rep. 15, 17753 (2025).

Belhadj, W., Timoumi, A., Dakhlaoui, H. & Alhashmi Alamer, F. Design and optimization of one-dimensional TiO2/GO photonic crystal structures for enhanced thermophotovoltaics. Coatings 12, 129 (2022).

Armenise, M. N., Campanella, C. E., Ciminelli, C., Dell’Olio, F. & Passaro, V. M. Phononic and photonic band gap structures: modelling and applications. Phys. Procedia. 3, 357–364 (2010).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Theoretical optimization of Tamm plasmon polariton structure for pressure sensing applications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 738 (2023).

Mohamed, A. G., Sabra, W., Mehaney, A., Aly, A. H. & Elsayed, H. A. Multiplication of photonic band gaps in one-dimensional photonic crystals by using hyperbolic metamaterial in IR range. Sci. Rep. 13, 324 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A. & Aly, A. H. Novel smart window using photonic crystal for energy saving. Sci. Rep. 12, 10104 (2022).

Wu, F., Lyu, K., Hu, S., Yao, M. & Xiao, S. Ultra-large omnidirectional photonic band gaps in one-dimensional ternary photonic crystals composed of plasma, dielectric and hyperbolic metamaterial. Opt. Mater. 111, 110680 (2021).

Tammam, M. et al. Defected photonic crystal array using porous GaN as malaria sensor. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 012005 (2021).

Zaky, Z. A., Alzahrani, A., Khedr, G. H., Elsharkawy, M. & Sallah, M. Radiation detector based on coupling between defect mode and topological edge state mode in photonic crystal. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–14 (2025).

Mohamed, A. M., Sabra, W., Mobarak, M., Shalaby, A. & Aly, A. H. Design of a 1D phc biosensor with enhanced sensitivity based on useful features provided for the detection of waterborne bacteria. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56, 433 (2024).

Aly, A. et al. Detection of reproductive hormones in females by using 1D photonic crystal-based simple reconfigurable biosensing design. Crystals 11, 1533 (2021).

Efimov, I., Vanyushkin, N., Gevorgyan, A. & Golik, S. Optical biosensor based on a photonic crystal with a defective layer designed to determine the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in water. Phys. Scr. 97, 055506 (2022).

Nayan, M. F. et al. High sensitivity one-dimensional photonic crystal sensor design for waterborne bacteria detection. Sens. Imaging. 26, 6 (2025).

Goyal, A. K., Kumar, A. & Massoud, Y. Performance analysis of heterostructure-based topological nanophotonic sensor. Sci. Rep. 13, 19415 (2023).

Rahimi, H. Analysis of photonic spectra in Thue-Morse, double-period and Rudin-Shapiro quasiregular structures made of high temperature superconductors in visible range. Opt. Mater. 57, 264–271 (2016).

Zhang, H. F., Hu, X. C. & Ma, Y. Wide-angle and ultra-wideband absorption in one-dimensional superconductor photonic crystals with quasi-periodic sequences. IEEE Access. 7, 164286–164293 (2019).

Ali, N. B. et al. Tunable multi-band-stop filters using generalized fibonacci photonic crystals for optical communication applications. Mathematics. 10, 1240 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zohny, E. I. & Aly, A. H. Refractive index sensor using fibonacci sequence of gyroidal graphene and porous silicon based on Tamm plasmon polariton. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 6 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Theoretical study of doped porous silicon in cantor quasi periodic structure for gamma radiation detection. Sci. Rep. 15, 14995 (2025).

Aissaoui, M., Zaghdoudi, J., Kanzari, M. & Rezig, B. Optical properties of the quasi-periodic one-dimensional genarilized multilayer fibonacci structures. Progress Electromagnet. Res. 59, 69–83 (2006).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Hendy, A. S., Zayed, M. & Aly, A. H. Gamma radiation detector using cantor quasi-periodic photonic crystal based on porous silicon doped with polymer. International J. Mod. Phys. B, p. 2450409, (2024).

Sayed, F. A. et al. Quasi periodic photonic crystal as gamma detector using poly nanocomposite and porous silicon. Sci. Rep. 15, 18451 (2025).

Trabelsi, Y., Ali, N. B. & Kanzari, M. Tunable narrowband optical filters using superconductor/dielectric generalized Thue-Morse photonic crystals. Microelectron. Eng. 213, 41–46 (2019).

Trabelsi, Y., Benali, N., Bouazzi, Y. & Kanzari, M. Microwave transmission through one-dimensional hybrid quasi-regular (Fibonacci and Thue-Morse)/periodic structures. Photonic Sens. 3, 246–255 (2013).

Alipour-Banaei, H., Serajmohammadi, S., Mehdizadeh, F. & Hassangholizadeh-Kashtiban, M. Special optical communication filter based on Thue-Morse photonic crystal structure. Optica Appl. 46, 145–152 (2016).

Zaman, N. A. et al. Simulation analysis of a highly sensitive biosensor for early detection of cancer cells based on a 1D photonic crystal. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technology, (2025).

Almawgani, A. H. et al. Highly sensitive nano-biosensor based on a binary photonic crystal for cancer cell detection. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54, 554 (2022).

Aly, A. H. & Zaky, Z. A. Ultra-sensitive photonic crystal cancer cells sensor with a high-quality factor. Cryogenics. 104 102991 (2019).

Men, Z. et al., GTP-modified gold nanoparticle-based four-core fiber sensor for ultrasensitive detection of chlorothalonil in environmental and food safety monitoring. IEEE Sens. Journal (2025).

Bansal, K., Kaur, B., Boddu, S., Kumar, S. & Marques, C. Machine learning integration in optical sensing: Trends, challenges and biomedical applications. IEEE Sens. Reviews, (2025).

Vaijayanthimala, J. & Kumar, A. Enhanced sensing of diseased blood samples through one-dimensional MgO-SiO2 photonic crystal sensor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 171, 107505 (2024).

Abohassan, K. M., Ashour, H. S. & Abadla, M. M. A 1D photonic crystal-based sensor for detection of cancerous blood cells. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53, 1–14 (2021).

Nayan, M. F. et al. A high-performance biosensor based on one-dimensional photonic crystal for the detection of cancer cells, Opt. Quant. Electron. 56, 2024 (1968).

Lang, X. et al. Chitosan-coated iron (III) oxide nanoparticles and tungsten disulfide quantum dots-immobilized fiber-based waveflex biosensor for staphylococcus aureus bacterial detection in real food samples. Sens. Actuators Rep. 8, 100239 (2024).

Fu, Q. et al. Signal-enhanced multi-core fiber-based waveflex biosensor for ultra-sensitive xanthine detection. Opt. Express. 31, 43178–43197 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Theoretical analysis of porous silicon one-dimensional photonic crystal doped with magnetized cold plasma for hazardous gases sensing applications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 584 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Hendy, A. S. & Aly, A. H. Studying the impact of interface roughness on a layered photonic crystal as a sensor. Phys. Scr. 98, 105527 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Zhaketov, V., Kozhevnikov, S. & Sallah, M. Photonic crystal with a defect layer of silicon containing polymer nanocomposites as radiation detector. Sci. Rep. 15, 7935 (2025).

Zaky, S. A. et al. Replacing toxic dyes with photonic crystals for printing applications: Simulation study. Applied Optics. 64, (2025).

Zaky, Z. A., Hennache, A. & Zhaketov, V. Terahertz metasensor with Pseudo parity time symmetry for oral cancer diagnostics. Sci. Rep. 15, 29424 (2025).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Defected photonic crystal as propylene glycol THz sensor using parity-time symmetry. Sci. Rep. 14, 23209 (2024).

Zaky, Z. A., Alamri, S., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Refractive index sensor with magnified resonant signal. Sci. Rep. 12, 13777 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Photonic crystal with magnified resonant peak for biosensing applications. Phys. Scr. 98, 055108 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Sharma, A. & Aly, A. H. Effective pressure sensor using the parity-time symmetric photonic crystal. Phys. Scr. 98, 035522 (2023).

Antraoui, I., Khettabi, A., Sallah, M. & Zaky, Z. A. Localized modes and acoustic band gaps using different quasi-periodic structures based on closed and open resonators. Sci. Rep. 15, 7633 (2025).

Zaky, Z. A., Antraoui, I., Malki, M. E., Khettabi, A. & Sallah, M. Tunability of acoustic band gaps using Thue Morse quasiperiodic lateral resonators. Sci. Rep. 15, 16183 (2025).

Trabelsi, Y., Ali, N. B., Segovia-Chaves, F. & Posada, H. V. Photonic band gap properties of one-dimensional photonic quasicrystals containing nematic liquid crystals. Results Phys. 19, 103600 (2020).

Fang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. J. Resonance-dependent extraordinary reflection and transmission in PC-symmetric layered structure. Opt. Commun. 407, 255–261 (2018).

Klimov, V. I. et al. Optical gain and stimulated emission in nanocrystal quantum dots. Science 290, 314–317 (2000).

Sim, Y. C., Park, J. Y., Ahn, K. M., Park, C. & Son, J. H. Terahertz imaging of excised oral cancer at frozen temperature. Biomedical Opt. Express. 4, 1413–1421 (2013).

Pandey, G. N., Suthar, B., Kumar, N. & Thapa, K. B. Omnidirectional reflectance of superconductor-dielectric photonic crystal in THz frequency range. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 34, 2031–2039 (2021).

Aly, A. H. et al. Photonic crystal enhanced by metamaterial for measuring electric permittivity in GHz range. Photonics 416 (2021).

Qin, P. et al. Angle-Insensitive toroidal metasurface for high-efficiency sensing. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 69, 1511–1517 (2020).

Sun, B., Yu, Y. & Yang, W. Enhanced toroidal localized spoof surface plasmons in homolateral double-split ring resonators. Opt. Express. 28, 16605–16615 (2020).

Andueza, Á., Pérez-Conde, J. & Sevilla, J. Differential refractive index sensor based on photonic molecules and defect cavities. Opt. Express. 24, 18807–18816 (2016).

Ge, X. & He, S. Experimental realization of an open cavity. Sci. Rep. 4, 5965 (2014).

Panghal, A. et al. Terahertz chemical sensor based on the plasmonic hexagonal microstructured holes array in aluminum. In 44th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves (IRMMW-THz) 1–2, (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.A. Zaky invented the original idea of the study, implemented the computer code, performed the numerical simulations, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the main manuscript text, and was the team leader. A. Hennache analyzed the data and discussed the results. I. Antraoui wrote and revised the main manuscript text, analyzed the data and discussed the results. A. Khettabi analyzed the data and discussed the results. Finally, all Authors developed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies involving animals or human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaky, Z.A., Hennache, A., Antraoui, I. et al. Using Thue Morse structure and magnified defect resonance as cancer sensor. Sci Rep 15, 39835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23454-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23454-5