Abstract

Retinal biometric parameters such as disc-fovea (DF) distance and optic disc diameter (DD) are widely used to assess retinal vascularization in premature infants, evaluating the severity of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). However, normative data for these measurements in neonates remain insufficient, and their relationship with ROP or intravitreal ranibizumab treatment is not well established. This study aimed to measure DF, DD, and DF/DD ratio in premature infants between 34 and 40 weeks of postmenstrual age (PMA), and to evaluate whether these parameters are influenced by the presence of ROP or intravitreal ranibizumab injection. A retrospective analysis was performed on wide-field fundus images from 120 premature infants, categorized into three groups: ROP infants treated with ranibizumab, ROP infants with spontaneous regression, and infants without ROP. The mean DD was 1.55 mm, showing no significant change across groups or over time. DF was 4.28–4.62 mm, displaying a decreasing trend with increasing PMA. The DF/DD ratio remained stable (3.05–3.30) across all PMA weeks and groups, with significant intergroup differences observed only at PMA 40 weeks. These findings suggest that these measurements are not significantly affected by ROP or ranibizumab treatment up to PMA 39 weeks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a proliferative retinal vascular disease that primarily affects premature infants due to incomplete vascularization of the retina at birth1. This condition results from preterm birth and exposure to high oxygen levels, which interfere with normal retinal vascular development. ROP remains one of the leading causes of childhood blindness worldwide, as its progression to advanced stages, particularly retinal detachment, can result in irreversible vision loss2. Early diagnosis and timely intervention are critical to prevent severe visual impairment3.

Screening guidelines emphasize the importance of monitoring at-risk infants, particularly those with a gestational age (GA) of less than 32 weeks or a birth weight of less than 1501 g4. Regular follow-up allows for early detection of abnormal vascular changes and allows clinicians to determine whether treatment is needed. According to the International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ICROP) 3rd edition5, the severity of ROP is classified based on the extent of retinal vascularization (zone), the severity of the disease (stage), and the presence of dilated and tortuous posterior polar vessels (plus disease). The degree of retinal vascularization in premature infants is divided into three zones of the retina, with zone I representing the most posterior region and this zone being at the highest risk of progression to severe ROP requiring treatment. Zone I ROP with plus disease requires immediate treatment within 72 h. In contrast, mild ROP occurring in zones II or III, such as stage I or II without plus disease, often resolves spontaneously and requires only follow-up monitoring.

Zone of ROP is critical to evaluate the severity and make decisions about when to initiate treatment or continue screening for at-risk infants. When assessing retinal vascularization, certain biometric parameters are widely used, including the disc-fovea (DF) distance unit and the optic disc diameter (DD) unit. The DF unit is measured from the center of the optic disc to the center of the fovea and is used as a standardized unit to assess the degree of retinal vascularization as suggested by ICROP 3rd edition5. The DD unit is suitable for quantifying the size of avascular areas in the peripheral retina6,7,8. Also, Bayramoglu & Sayin6 attempted to assess retinal vascularization using the DD unit, in addition to the DF unit, and revealed slight differences in results, probably due to variations between groups and examination methods. On the other hand, the DF/DD ratio is a simple yet significant parameter for diagnosing optic nerve hypoplasia in infants9. Given that the growth rates of DF and DD may differ in premature infants, DF/DD ratio is also likely to differ from that of full-term or normal infants.

Nowadays, with the advancement of imaging technology, wide-field contact digital fundus imaging has emerged as a more accurate and reliable method to measure these parameters compared to traditional indirect ophthalmoscopy. However, despite these advancements, comprehensive data on DF and DD values,10,11 especially in premature infants, are still lacking. Given that eye growth, retinal vascularization, and the presence or absence of ROP may affect these measurements, further studies are needed to establish a standardized DF/DD ratio. Therefore, this study aimed to assess changes in the distance between the optic disc and the fovea in premature infants using wide-field fundus imaging. We evaluated DD, DF, and the DF/DD ratio across different postmenstrual ages (PMA) and examined whether the presence and severity of ROP, as well as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injection (anti-VEGF) treatment, influenced changes in DF and DD. The authors hypothesized that characteristics such as DD and DF would change with increasing PMA, the development of ROP, and the anti-VEGF injections.

Methods

Study design

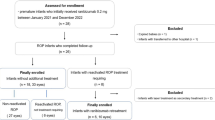

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital (IRB No. 2024-10-003) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of the study and the use of fully anonymized patient data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB of Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital. We retrospectively analyzed premature infants using serial wide-field fundus imaging taken at 1- to 2-week intervals at 34–40 weeks of PMA between August 2018 and March 2024. Among premature infants who underwent ROP screening, those who 1) were unable to take ROP images due to poor general condition or transfer to another hospital, 2) had an interval of more than 2 weeks between consecutive photographic images during the 34–40 weeks of PMA period, 3) had consecutive photographic images with poor quality were excluded. 4) Infants who received treatment other than ranibizumab injection were also excluded. Then, subjects were divided into three groups: ROP patients who treated with ranibizumab (Group 1), ROP patients with spontaneous regression (Group 2), and preterm infants without ROP (Group 3) (Fig. 1).

Screening & follow-up for ROP

All infants with a GA less than 32 weeks or a body weight less than 1501 g were screened for ROP. For infants born before 31 weeks of GA, we performed the first ROP screening at 31 weeks PMA or 4 weeks of postnatal age, whichever was later. For infants born at or after 31 weeks of GA and weighing less than 1501 g, we performed the first ROP screening at 36 weeks of PMA or 4 weeks of postnatal age, whichever came first.

Retinal examinations were performed without sedation under pupil dilation by a retina specialist ophthalmologist (J.H.J) in the neonatal intensive care unit or a specialized retinal care unit. After direct retinal examination using a 20D Volk lens and an indirect ophthalmoscope, retinal images were obtained using a wide-angle 130° retinal photo (RetCam; Natus Medical Incorporated, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Infants with aggressive ROP or type 1 ROP were treated with intravitreal ranibizumab injection (0.2 mg in 0.02 ml) within 48 h of diagnosis.

The follows up exams were followed at 1 or 2 weeks of interval, depending on the severity of the fundus state. Preterm infants without ROP were followed until complete vascularization in Zone III or until PMA 45 weeks. Infants with spontaneous regression of ROP were followed until complete regression or PMA 55 weeks. Infants who received ranibizumab therapy were followed until PMA 70 weeks without further treatment if there was no reactivation.

Measurement of disc diameter and disc-fovea distance using wide-field fundus images

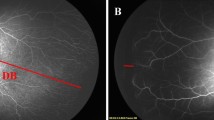

We reviewed serial wide-field retinal images obtained from each infant between 34 and 40 weeks of PMA. For each time point, one retinal image of the highest quality was selected to ensure clear identification of the optic disc and fovea. Two retina specialists (J.K and J.H.J) measured the horizontal and vertical DD, and DF using Image J software (version 18.0, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA) at a resolution of 1600 × 1200 pixels (Fig. 2). The DF line was defined as the straight line connecting the fovea and the center of the optic disc. The vertical DD was defined as the line passing through the disc center and aligned with the longest vertical axis of the optic disc. The horizontal DD was defined as the longest distance between the nasal and temporal disc margins through the disc center. The mean DD was calculated as the average of the horizontal DD and vertical DD. The DF/DD ratio was calculated by dividing the DF value by the mean DD. We measured three angular parameters as complementary indices to the linear DF/DD ratio: (1) θDF, the angle between the DF line and the vertical DD; (2) θa, the angle between the temporal superior arterial arcade and the DF line; and (3) θb, the angle between the temporal inferior arterial arcade and the DF line. 9,12 All measurements represent the average of the two observers’ values; inter-observer variability was not assessed. Pixel measurements were converted to millimeters using the manufacturer’s calibration of 0.0122 mm/pixel6. These angles measurements were performed using the angle tool in ImageJ and expressed in degrees. The measured parameters were compared and analyzed across the three groups.

Measurement of horizontal and vertical disc diameters (DD), disc-fovea distance (DF), and three angular parameters on a wide-field retinal image from an infant with retinopathy of prematurity and ridge formation. The horizontal DD is shown as a black line, the vertical DD as a white line, and the DF as a blue line. The angles measured include θDF, the angle between the DF line and the vertical DD; θa, the angle between the temporal superior arterial arcade and the DF line; and θb, the angle between the temporal inferior arterial arcade and the DF line.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as means with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. To compare the three groups, Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous variables. In addition, pairwise comparisons between groups were conducted using the Bonferroni post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R (version 4.2.2; R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The retinal images of 120 infants were included in this study. Among 120 infants, Group 1 had 28 subjects, Group 2 had 32 subjects, and Group 3 had 60 subjects. The sex, gestational age, birth weight, and PMA at the time of the first examination for each group are summarized in Table 1.

The mean values of horizontal DD at PMA 34 weeks for each group were as follows: Group 1, 1.19 ± 0.12 mm; Group 2, 1.23 ± 0.09 mm; and Group 3, 1.23 ± 0.11 mm, with no significant differences (p = 0.270). At PMA 40 weeks, the values were 1.20 ± 0.12 mm for Group 1, 1.25 ± 0.09 mm for Group 2, and 1.23 ± 0.13 mm for Group 3, again showing no significant differences (p = 0.388). No significant changes in horizontal DD were observed either between groups at each time point or within each group from PMA 34 to 40 weeks.

For vertical DD, the mean values at PMA 34 weeks were: Group 1, 1.58 ± 0.15 mm; Group 2, 1.61 ± 0.09 mm; and Group 3, 1.61 ± 0.13 mm, with no significant differences (p = 0.575). At PMA 40 weeks, the mean DF values were 1.60 ± 0.22 mm in Group 1, 1.62 ± 0.11 mm in Group 2, and 1.50 ± 0.11 mm in Group 3, showing a statistically significant difference among the three groups (p = 0.006). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between Group 1 and Group 3 (p = 0.049) and between Group 2 and Group 3 (p = 0.010).

Similarly, at 34 weeks of PMA, the mean DD values were 1.39 ± 0.13 mm in Group 1, 1.42 ± 0.08 mm in Group 2, and 1.42 ± 0.10 mm in Group 3, with no statistically significant differences among the groups (p = 0.360). At 40 weeks of PMA, the mean DD values were 1.40 ± 0.16 mm in Group 1, 1.43 ± 0.08 mm in Group 2, and 1.37 ± 0.10 mm in Group 3, also showing no significant differences (p = 0.088). Throughout the study period, from PMA 34 to 40 weeks, no significant changes in mean DD were observed either between the groups at each time point or within each group over time (Table 2).

Regarding the mean DF values at 34 weeks of PMA, the measurements were as follows: 4.52 ± 0.43 mm in Group 1, 4.64 ± 0.28 mm in Group 2, and 4.62 ± 0.22 mm in Group 3, with no statistically significant differences among the groups (p = 0.319). However, at 40 weeks of PMA, the mean DF values were 4.46 ± 0.19 mm in Group 1, 4.35 ± 0.19 mm in Group 2, and 4.29 ± 0.18 mm in Group 3, showing a significant difference among the groups (p = 0.002, Table 3). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference specifically between Group 1 and Group 3 (p = 0.002, Table 3).

For the DF/DD ratio at 34 weeks of PMA, the mean values were as follows: 3.28 ± 0.32 in Group 1, 3.29 ± 0.30 in Group 2, and 3.27 ± 0.27 in Group 3, with no significant differences among the groups (p = 0.952). No significant differences in the DF/DD ratio were observed among the groups from PMA 34 to 39 weeks, except at 40 weeks of PMA. At 40 weeks of PMA, the ratios were 3.23 ± 0.32 in Group 1, 3.05 ± 0.21 in Group 2, and 3.16 ± 0.26 in Group 3, showing a statistically significant difference among the groups (p = 0.038). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between Group 1 and Group 2 (p = 0.035, Table 4).

When comparing θDF, θa, and θb among the three groups from PMA 34 to 40 weeks, significant differences were observed in θDF at PMA 34–38 weeks and in θb at PMA 34–40 weeks (except at PMA 35 weeks). A significant difference in θa was noted only at PMA 38 weeks. Across all groups, θDF increased with advancing PMA, whereas θa and θb showed a decreasing trend (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to establish baseline biometric values for DF, DD, and DF/DD ratio in preterm infants and provide reference for future studies on the degree of retinal development and risk assessment of ROP. In particular, we investigated whether these values change with increasing PMA, whether they change with the presence and severity of ROP, and whether anti-VEGF injection treatment affects the changes in DF and DD.

In this study, comparing the mean DD, DF, and DF/DD ratio, no significant differences were observed among three groups, except for the DF value and DF/DD ratio at 40 weeks of PMA. The mean ratios for all periods ranged from 3.05 to 3.30. Although DF tended to decrease as PMA increased, there were no significant differences among the three groups, except at PMA 40 weeks. These findings suggest that the DF/DD ratios and DF values remain unaffected by the occurrence of ROP or anti-VEGF treatment up to PMA 39 weeks. However, the decrease in DF with increasing PMA weeks indicates a potential relationship between DF and overall eye growth or axial length elongation.

The DF and DD are simple but important anatomical markers of the posterior pole of the retina. The DF/DD ratio has been an important diagnostic criterion for diagnosing or suspecting optic nerve hypoplasia (ONH). Barr et al.9 reported threshold DF/DD ratio values for diagnosing unequivocal ONH as 4.20 for adults, 3.93 for 5-year-old children, and 3.70 for 2-year-old children, indicating that the previously suggested threshold of 3.00 is too low. The study9 also highlighted that the DF/DD ratio can be affected by factors such as disc rotation, foveal displacement, and refractive errors, particularly high myopia. Meanwhile, Sato et al.13 reported the DF/DD ratio in healthy Japanese adult men and women as 2.91 ± 0.49, 2.96 ± 0.54 respectively. Pang and Pang & Frantz14 measured the optic disc area and DF/DD ratio using Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph. They found that the optimal cutoff value for disc area to diagnose ONH was 1.42 mm2, with a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 85%, and the optimal cutoff value for DF/DD ratio was 3.20, with a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 78%.

However, in infants, advanced imaging modalities such as OCT or Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph are not widely available due to their high cost and limited accessibility. In such cases, measuring DF and DD values from fundus photographs alone can serve as a practical and valuable alternative for assessing ocular abnormalities. Our study is significant in that we measured DD, DF, and DF/DD ratio serially from PMA 34 to 40 weeks using serial wide-field retinal photographs in preterm infants.

De Silva et al.10 measured the DD and DF in preterm and full-term infants (PMA 32 to 50 weeks) using fundus imaging. They reported that the mean DF/DD ratio was 3.76, with no significant difference between preterm and full-term infants. Additionally, the mean DF was 4.4 ± 0.4 mm, while the horizontal DD and vertical DD were 1.05 ± 0.13 mm and 1.41 ± 0.13 mm, respectively. In our study, the DF/DD ratio ranged from 3.05 to 3.30 across all groups, regardless of PMA, with an average of 3.21. The mean DF was 4.48 ± 0.09 mm, while the horizontal DD and vertical DD measured 1.21 ± 0.02 mm and 1.58 ± 0.05 mm, respectively. Notably, the DF/DD ratio in preterm infants in our study was lower than that reported by De Silva et al.10 (3.21 vs. 3.76). However, there was no significant difference in DF measurements between the two studies (4.48 mm vs. 4.4 mm). This study suggests that the lower DF/DD ratio in preterm infants may be attributed to a relatively larger optic disc diameter rather than differences in the disc-foveal distance. A study by Prakalapakorn et al.15 found that non-White race in preterm infants was significantly associated with longer axis length, which in turn was correlated with larger optic disc diameter.

Our study found that DF showed a decreasing trend in all three groups as PMA increased, which may be related to the elongation of axial length (AL). The greatest decrease in DF was observed in preterm infants without ROP, followed by those with spontaneously regressed ROP, and finally, those who received anti-VEGF treatment. This suggests that as PMA increases, AL lengthens, leading to relatively shorter DF measurements by capturing wider area. Wang et al. 16 calculated the area of Zone I using multiple ocular parameters, including AL, anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, corneal power, and lens power. Their study found that as AL increased, Zone I area also expanded; specifically, when AL increased from 14.20 mm to 16.58 mm, Zone I area could increase by up to 72%. This difference in results is believed to be due to the fact that, unlike previous study16, our study did not directly calculate the DF distance by measuring AL. Therefore, the observed trend of decreasing DF with increasing AL may be attributed to this limitation. However, the decreasing trend of DF observed between 34 and 40 weeks of gestational age suggests that an increase in AL occurred during this period, and further indicates that eyes without ROP grow faster than those in ROP. This finding is consistent with previous study; Prakalapakorn et al.15 found that AL increased linearly up to PMA 42 weeks. Additionally, Clark et al.17 reported that in untreated ROP, AL increases from 15.3 to 16.3 mm, whereas in treated ROP, the growth was smaller, from 15.0 to 15.7 mm between PMA 34 weeks to 50 weeks.

In this study, instead of measuring AL directly, we evaluated θDF, θa, and θb as surrogate parameters. Across PMA 34 to 40 weeks, θDF increased while θa and θb decreased, and the change was greater in the normal group than in the ROP groups (Groups 1 and 2). These findings are consistent with the expected influence of increasing AL, in which θa, and θb decrease due to widening of the temporal arcades and θDF increases as a result of optic disc tilt and temporal displacement of the fovea. The Gutenberg Prematurity Eye Study 18 reported that optic disc tilt, which is associated with myopia, is more common in adults who received laser or cryotherapy for ROP. So, further research is needed to determine whether anti-VEGF treatment has any long-term effects on optic disc morphology.

In our study, the DF and DF/DD values were significantly different among the three groups at PMA 40 weeks. There may be several reasons why these differences were observed only at PMA 40 weeks. First, differences in retinal vascular development or eye growth between the groups may become more noticeable as PMA 40 weeks approaches. Second, ranibizumab injection may have affected DF size and DF/DD ratio. In addition, factors such as sample size and measurement error may have played a role.

This study has several limitations. First, because it is a retrospective, single-center study, the results may not be generalizable to other populations or settings. Second, there is a potential for inter-examiner variability in the measurement of DD, DF dimensions and three angle parameters using the ImageJ program, which may have influenced the results. However, we attempted to minimize this error by performing cross-measurements and averaging the values. Third, because this study included only a short-term observation period focusing on preterm infants with serial fundus images taken between 34 and 40 weeks of PMA, it may not have captured long-term changes in the DF/DD ratio. Finally, the lack of AL measurements limits the ability to fully assess the potential impact of DF, DD, and DF/DD ratio on related outcomes. In the future, incorporating variables such as AL or utilizing advanced equipment like OCT could enable more precise measurements of DF and the DF/DD ratio.

Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful in that it provides approximate values for DF and DD according to PMA weeks in premature infants and examines whether the DF/DD ratio varies depending on whether ROP occurred or anti-VEGF treatment was administered. Furthermore, the DD of preterm infants between PMA 34 and 40 weeks ranged from 1.33 to 1.42 mm, DF from 4.28 to 4.62 mm (mean: 4.48 ± 0.09 mm), and the DF/DD ratio from 3.05 to 3.30 (mean: 3.21), providing valuable clinical reference data. To better understand the ROP zone, future studies should focus on collecting comprehensive baseline data on DF and DD size along with additional parameters such as AL and eye growth rate to provide a more detailed understanding of ocular development in premature infants.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yehiam, S. Z. et al. Incomplete peripheral retinal vascularisation in retinopathy of prematurity: Is it the consequence of changing oxygen saturation?. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1203068 (2023).

Sabri, K., Ells, A. L., Lee, E. Y., Dutta, S. & Vinekar, A. Retinopathy of prematurity: A global perspective and recent developments. Pediatrics 150(3), e2021053924 (2022).

Chang, J. W. Risk factor analysis for the development and progression of retinopathy of prematurity. PLoS ONE 14(7), e0219934 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Optimised retinopathy of prematurity screening guideline in China based on a 5-year cohort study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105(6), 819–823 (2021).

Chiang, M. F. et al. International classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology 128(10), e51–e68 (2021).

Bayramoglu, S. E. & Sayin, N. Inter-eye comparison of retinal vascular growth rate and angiographic findings following unilateral bevacizumab treatment. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32(3), 1430–1440 (2022).

Mintz-Hittner, H. A., Geloneck, M. M. & Chuang, A. Z. Clinical management of recurrent retinopathy of prematurity after intravitreal bevacizumab monotherapy. Ophthalmology 123(9), 1845–1855 (2016).

Wu, L. et al. Evaluation of retinal vascularization in retinopathy of prematurity regressed after intravitreal ranibizumab monotherapy or without treatment based on fluorescein angiography. Sci. Rep. 13, 19946 (2023).

Barr, D. B., Weir, C. R. & Purdie, A. T. An appraisal of the disc-macula distance to disc diameter ratio in the assessment of optic disc size. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 19(5), 365–375 (1999).

De Silva, D. J. et al. Optic disk size and optic disk-to-fovea distance in preterm and full-term infants. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47(11), 4683–4686 (2006).

Feng, X. et al. Comparative study on optic disc features of premature infants and full-term newborns. BMC Ophthalmol. 21(1), 120 (2021).

Jonas, J. B., Weber, P., Nagaoka, N. & Ohno-Matsui, K. Temporal vascular arcade width and angle in high axial myopia. Retina 38(9), 1839–1847 (2018).

Sato, K. I. Reference interval for the disc-macula distance to disc diameter ratio in a large population of healthy Japanese adults: A prospective, observational study. Medicine 96(15), e6613 (2017).

Pang, Y. & Frantz, K. A. Comparison of heidelberg retina tomograph with disc-macula distance to disc diameter ratio in diagnosing optic nerve hypoplasia. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 36(3), 317–323 (2016).

Prakalapakorn, S. G. et al. Evaluating the association of clinical factors and optical coherence tomography retinal imaging with axial length and axial length growth among preterm infants. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259(9), 2661–2669 (2021).

Wang, S. K. et al. Modeling absolute zone size in retinopathy of prematurity in relation to axial length. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 4717 (2022).

Cook, A., White, S., Batterbury, M. & Clark, D. Ocular growth and refractive error development in premature infants without retinopathy of prematurity. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44(3), 953–960 (2003).

Fieß, A. et al. Optic nerve head morphology in adults born extreme, very, and moderate preterm with and without retinopathy of prematurity: Results from the gutenberg prematurity eye study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 239(7), 212–222 (2022).

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.J conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, collected data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. J.K collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript. S.P.B designed the data collection instruments. N.H.S carried out the entire statistical analyses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwak, J., Son, NH., Bang, S.P. et al. Biometric analysis of disc-fovea distance and optic disc diameter in premature infants using wide-field fundus imaging. Sci Rep 15, 39834 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23462-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23462-5