Abstract

This research aims to develop a sustainable concrete matrix incorporating fire clay, rice husk, and fly ash. This study investigates the use of fire clay (FC) as a partial substitute for sand, fly ash (FA), and rice husk (RH) in cement-based concrete mixes to enhance sustainability, reduce costs, and improve mechanical and microstructural properties. Concrete specimens with varying levels FC replacement (0%, 12%, 25%, 36%, and 50%), FA, and RH (0, 4%, 8%, 12%, 16%) were tested for compressive and flexural strength at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to investigate changes in microstructural and phase composition. The results demonstrated a progressive decline in mechanical properties with increased FA, RH, and FC content, primarily due to the dilution effect of FA, RH, and FC particles, which disrupt the cementitious matrix and weaken structural integrity. The control mix had a compressive strength of 29.32 MPa, whereas the mix with 8% FA, 8% RH, and 25% fire clay replacement had a compressive strength of 31.65 MPa, a 2.5% increase with equivalent mechanical properties. After an acid attack, the control mix had decreased hydration products, whereas the FA, RH, and FC replaced mixes had sustained quartz peaks, indicating structural integrity. SEM study showed that FA, RH, and FC enhance the porosity of the cement matrix and micro-cracks after acid exposure, but improve packing density and stability before acid exposure. Furthermore, a two-way statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a p-value of less than 0.001 and R-squared (R²) values ranging from 0.925 to 0.954 demonstrated that the model is statistically significant. By optimising the substitution levels of FA, RH, and FC, the importance of achieving the desired mechanical and microstructural properties while maximising sustainability benefits can be further enhanced. This research advances sustainable construction practices by demonstrating the potential of FA and RH as partial cement substitutes and FC as a fine aggregate substitute. The results facilitate the development of sustainable concrete technology and the implementation of environmentally favourable construction practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is a multifaceted material used for several applications within the construction sector. Portland Cement (PC) is the primary component in concrete production, contributing 8% to 10% of total world anthropogenic CO2 emissions1,2. According to reports, global cement production in 2018 exceeded 4.5 billion tonnes3. Moreover, resource depletion, dust, and particle emissions substantially exacerbate environmental consequences, resulting in an elevated global warming potential. The use of alkali-activated materials binders as building materials is recognized as a superior alternative to Portland cement, as they transform waste aluminosilicate materials into an environmentally friendly and sustainable construction resource4,5.

To address the challenges associated with PC, researchers6,7 have lately concentrated on the viability of integrating sustainable development by identifying alternatives to PC to mitigate the carbon footprint of the cement production sector. Low-calcium fly ash (FA) and rice husk ash (RH), which are abundant in alumina (Al) and silica (Si), are regarded as waste by-products from industrial and agricultural processes, respectively, that can be used as precursor materials in green concrete8. Fly ash is derived from coal-fired power stations, while rice husk (RH) is generated in rice mills, mainly in Asian nations. Each year, approximately 120 million tonnes of rice husk ash (RH) are generated worldwide, posing a significant environmental challenge due to its direct disposal into the ecosystem9,10. RH has extremely irregular, porous, cellular particles, has a low bulk unit weight9, and demonstrates significant reactivity owing to its extensive exterior surface area, which amplifies its pozzolanic reactivity11,12. In previous research, industrial waste has been partially used as a substitute for fine aggregate in concrete. Examples include waste foundry sand, fly ash, glass polishing powder, rice husk ash, limestone powder, demolition materials, calcium carbonate residues, sugarcane bagasse ash, wheat straw ash, and ceramic powder wastes, which are also used as cement replacements. Besides these instances, fire clay has partially replaced aggregates13,14,15.

Fireclay is a heat-resistant clay used in the construction industry. FC is a popular building material due to its insulation and production efficiency16,17. Its outstanding thermal shock endurance, heat resistance, and abrasion resistance earned it this praise18. Thus, it is often used to make firebricks for fireplaces, furnaces, and other high-temperature environments. It is also essential to make refractory materials that can withstand high temperatures. Its structural composition shows 50–60% silica and 18–44% alumina19,20. FC is known for its chemical corrosion resistance, durability, and heat resistance. Because it can retain its shape and withstand water and other liquids, it is often used to make ceramics, such as tableware and bathroom fixtures21,22. This trash includes fireclay product remnants, trimming and cutting waste, and bulkiness, which makes disposal difficult due to sluggish biodegradability23,24,25. Researchers have explored methods to utilize industrial waste in the production of heat-resistant bricks, concrete, polymers, and iron26,27,28. This exchange reduces manufacturing raw material costs and promotes waste recycling29,30. Arbili et al.31 compared the forming and sintering of fine fire clay with the changed particle sizes of the raw materials. Their investigation found that two particle-size distributions in FC composition were more efficient than one32,33. Joyklad et al.34 tested brick debris as an alternative to concrete coarse aggregate. The research used coarse aggregates from crushed, burned clay bricks in concrete at 50% and 100% replacement levels. The study investigated the impact of these replacements on the density, compressive strength, tensile splitting strength, modulus of elasticity, and stress-strain behaviour of concrete. Strength-related concrete qualities declined as the clay brick aggregate fraction increased35.

Miah et al.36 examined the mechanical properties of brick aggregates (BA) in concrete. They found that BA-formulated concrete had lower mechanical strength and greater permeability than normal concrete. SEM examination of BA and concrete with burned clay BA showed greater voids and fractures in BA, owing to mechanical property differences36. Hafez et al.37 investigated the impact of FA and RH on the compressive strength of hardened concrete (CS). The research optimized FA and RH in concrete mixtures to enhance the performance of concrete. Overall, FA-containing concrete performed better than normal concrete37. Muñoz et al.38 investigated the use of firing clay bricks with industrial and agricultural wastes. The study demonstrated that utilising waste materials conserves natural resources by minimising the use of raw materials and reducing industrial energy consumption. The method also reduced the carbon footprint of brick production. These studies demonstrate that repurposed waste materials can enhance the sustainability and physical properties of building materials, thereby supporting more sustainable construction38. Zhang et al.39 shed light on the use of fire clay and other waste materials in concrete blocks. Fired clay concrete blocks containing waste were tested for physical, mechanical, and thermal properties. Waste materials can enhance the thermal insulation and mechanical strength of building materials, thereby improving their properties40. Many researchers have explored the use of recycled plastic aggregate concrete, replacing the coarse aggregate in concrete with silica fume and granite waste at varying ratios to cement, typically combined with mineral admixtures, to enhance fire resistance, thermal performance, and the properties of the concrete41,42,43.

Due to the absence of standard procedures, optimising concrete mix design with multiple characteristics is a challenging task. Therefore, RSM was employed for optimization45. The response surface approach revealed that experimentation and testing required a significant amount of time and effort. He thought creative brainstorming might cut these resource costs. This led to an experimental design philosophy that delivers a significant quality improvement discipline, unlike previous techniques46,47. The response surface approach develops “robust” production processes that are indifferent to environmental and equipment damage. Using well-built tables, the statistical approach ANOVA provides resilience and efficient testing. This idea is used to catalogue orthogonal arrays via the response surface approach. Experimental testing was conducted to determine whether Response surface methods can optimise concrete mix design. Results showed that the RSM may be used to develop concrete mixes with results comparable to existing procedures. This suggests that the RSM can optimize concrete mixes for both resource efficiency and enhanced concrete performance48,49.

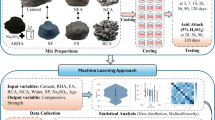

Fire clay replacement sand, a percentage of 12% to 50%, and fly ash and rice husk replacement, a cement percentage of 4% to 16%, were used to alter the microstructural and phase composition, which was studied using advanced characterization methods, including mechanical properties, RSM, XRD, and SEM. XRD measurement reveals variations in hydration products and the inclusion of fire clay in the crystalline phases of the cement matrix. SEM microstructure pictures show the hydration product and the distribution and shape of fire clay particles. These methods help determine the durability and performance of fire clay-substituted concrete under different climatic conditions by linking microstructural changes with mechanical parameters. Data analysis and visualization were employed to illustrate the compressive strength effects of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional contour plots, as well as 3D surface plots, demonstrate the relationship between compressive strength, fly ash, rice husk, fire clay content, and curing age.

Methods and materials

Preparation of specimens

This study’s experimental design investigated the effect of replacing cement with FA and RH with a percentage of 4% to 16% fine fire clay (FC) at varying percentages (12%, 24%, 36%, and 50%) on the compressive, flexural strength, XRD, and SEM analysis of the concrete mixtures. The study material and experimental methodology flowchart are illustrated in Fig. 1. The mix proportions were established based on the ACI codes47 for coarse aggregate, sand, and water-to-cement ratios, ensuring consistency and comparability across different mixtures. The mixed proportions for casting specimens are shown in Fig. 1.

Cylindrical specimens were cast with a diameter of 150 mm and a height of 300 mm to test the compressive strength, while beam specimens were cast with dimensions of 150 mm width, 150 mm depth, and 450 mm length to test the flexural strength. Detailed specifications for specimen dimensions and testing procedures are provided in Fig. 1. Through this experimental design, the study aimed to assess the impact of FA, RH, and FC incorporation on concrete mixtures’ compressive strength and flexural strength properties, providing insights into the feasibility of utilizing fly ash, rice husk partial substitute for cement, and fire clay as a partial substitute for sand in concrete making. Table 1 demonstrates the mixed-design concrete used in the experiment.

Materials

Cement

This study utilized 43-grade Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) that conforms to ASTM C 150 standards for Type I cement48. The cement, sourced locally for convenience and accessibility, was carefully selected to maintain freshness and avoid moisture contamination, which is crucial for achieving consistency and optimal performance in test specimens. The cement’s uniform grey color indicates its purity and standard composition, reflecting stringent quality control measures applied during procurement and handling, which are vital for ensuring the reliability of experimental outcomes. Tables 2 and 3 detail the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of the cement in the substance.

Fly Ash and rice husk

Rice husk (RH) was acquired from a local rice mill in Pakistan, while low-calcium (Class F) fly ash from a coal power plant, which adheres to ACI standards code47, was obtained from the coal power mill in Pakistan. Table 1 summarizes the chemical composition of primary materials, fly ash, and rice husk. The RH was ground into fine particles and subsequently sieved to obtain particles with a diameter of 75 μm or less. Nevertheless, prior research10 has indicated that the material’s particulate size should be at least 80% below 45 μm in order to achieve the highest possible strength. In order to prevent the practical challenges associated with the grinding process for industrial applications, a 75 μm limit was established.

Coarse aggregate

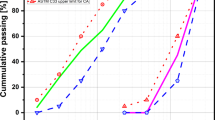

Locally sourced coarse aggregates were meticulously selected for their quality and durability. These aggregates underwent rigorous screening and washing to remove impurities, ensuring consistency in physical properties. The gradation adhered to industry standards, optimizing packing density and interlocking within the concrete matrix. Their excellent angularity and particle shape facilitated robust interparticle bonding, enhancing mechanical properties such as compressive and flexural strength. Control tests illustrate and validate the performance of the concrete formulations. These tests were conducted by relevant ASTM specifications49, ensuring accuracy and reliability. Figure 2 illustrates the well-graded nature of the coarse aggregate, further emphasizing its suitability for use in concrete mixtures. The choice of these aggregates reflects a commitment to quality, durability, and performance in concrete formulations. Table 4 shows the physical properties of coarse aggregates.

Fine aggregate

Carefully selected fine aggregates were integral to achieving optimal workability and cohesion in our concrete mixtures. Sourced locally, these aggregates underwent rigorous screening and washing to remove contaminants, ensuring consistency in their physical properties. Gradation adhered to industry standards49, promoting optimal particle packing within the concrete matrix. Control tests were conducted, as detailed in Table 1, to validate the performance of the concrete formulations. The tests were conducted in accordance with relevant industry standards, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the assessment of the fine aggregates’ quality. Furthermore, Fig. 3 illustrates the well-graded nature of the fine aggregates, further emphasizing their suitability for use in our concrete mixtures. Table 5 shows the physical properties of the fine aggregates.

Fire clay

Fire clay, serving as a partial substitute for sand in our concrete formulations, was selected for its abundance, cost-effectiveness, and potential environmental benefits. Carefully sourced from reliable suppliers, the fire clay underwent stringent testing to ensure its suitability and consistency as a sand substitute. Substitution levels ranging from 0%, 12%, and 50% were determined based on industry standards and previous research findings. Table 6 provides an overview of the chemical composition of the fire clay utilized in our study. These properties were essential in evaluating the impact of fire clay on the performance and characteristics of the concrete mixtures.

Mixing of the material

The mixing approach used in this investigation adhered closely to the established methods detailed in other studies29,30, thereby ensuring methodological consistency and reliability. The raw ingredients, including fire clay waste, fly ash, and rice husk, were meticulously integrated and blended at a regulated low speed of 160 rpm for three minutes to commence the mixing process. The primary objective of this initial mixing stage was to achieve a homogeneous distribution of the dry components, thereby facilitating their efficient interaction. After the first amalgamation, water and a superplasticiser were added to the mixture. The use of superplasticiser is crucial, since it enhances workability and fluidity without undermining the concrete’s overall strength. The mixture was swirled at a regulated low speed of 160 rpm for an additional three minutes. The gradual mixing ensured that the water and superplasticiser were completely incorporated into the dry constituents, thereby enhancing uniformity within the mixture. In the final phase of the mixing process, several materials—each chosen for its unique features and advantages—were carefully integrated into the concrete mix.

The strategic integration of these different material types in the mixing process enhances the concrete’s mechanical and microstructural properties, modifying its performance to meet the unique requirements of various applications. The mixing speed was increased to 385 rpm to ensure adequate dispersion of these components. The increased speed facilitated superior mixing, providing a uniform distribution of ingredients within the concrete matrix. The mixing procedure lasted for four minutes to ensure the thorough amalgamation of all components—the dry ingredients, water, and superplasticiser. The meticulous focus on the mixing process was crucial for attaining the required characteristics of the final concrete mix. Figure 3 displays the pictures of the mixes post-mixing. The presence of various elements protruding from the concrete mix might disrupt the appropriate setting and finishing processes, thereby compromising both the structural integrity and aesthetic quality of the finished product.

Test of specimens

Compressive strength (CS)

Mechanical strength experiments were conducted using a universal testing machine in accordance with ASTM C39/C39M50 standard procedures. Cylindrical specimens were cast with a diameter of 150 mm and a height of 300 mm to test the compressive strength. These tests were conducted at the ages of 3, 7, 14, and 28 days to evaluate the mechanical properties of various concrete mixtures. The controlled mix (CS-0) represented the standard concrete mixture, where cement served as the sole binder, with no substitutions. The Universal Testing Machine (UTM) used for testing concrete cylinders to determine compressive strength is shown in Fig. 4 (a and b).

Flexural strength (FS)

The flexural strength indices of the strength distribution diagrams for the fire clay concrete and control specimens were derived from a three-point flexural test performed with a UTM testing machine, as shown in Fig. 4(b). This approach is advantageous for evaluating the performance of materials under flexural loads, offering insights into how various material compounds improve the mechanical properties of concrete. The three-point flexural test was conducted according to ASTM C39/C39M50, which outlines the precise specifications for sample size, equipment configuration, and testing protocols. Simultaneously, beam specimens of 150 mm in width, 150 mm in depth, and 450 mm in length were cast to evaluate their flexural strength. The UTM testing machine was designed to exert weights of up to 50 kN while maintaining the integrity of the test. The dimensions of the specimens conformed to the specifications outlined in ASTM C39/C39M50, which mandates that the height and breadth of the specimens must be three times the length of those containing fire clay, fly ash, and rice husk. This design consideration is crucial for ensuring that the various materials effectively enhance the overall performance of the concrete.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis determines the material’s crystalline structure. XRD provides detailed information on crystal structures, phases, preferred crystal orientations, average grain size, crystallinity, strain, and crystal defects by directing X-rays at a material and measuring the diffracted beam angles and intensities51. XRD peaks show the lattice structure’s atomic distribution, making it useful for analysing the material’s atomic arrangement. The microstructure that unites all concrete particles is crucial to their strength. Cement, the reactive binder phase in concrete, hydrates to form this microstructure [52]. Several ways are used to compute the areas under XRD curves to estimate material crystallinity. These approaches presume the X-ray diffraction pattern has a crystalline and amorphous portion. Further study considers computed areas proportional to phase volumes [53].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is utilized to analyze the microstructural properties of concrete [53]. SEM employs a focused beam of high-energy electrons to generate detailed images of the material’s surface topography and composition. These high-resolution images reveal the distribution and morphology of hydration products and additives, such as fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content particles, within the concrete matrix. This analysis is crucial for understanding the impact of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content substitution on the material’s performance and durability. SEM not only aids in visualizing microstructural features but also identifies potential defects, thereby supporting the optimization of concrete mix designs for enhanced performance and sustainability in construction applications.

Response surface methodology

The RSM is a sophisticated statistical model that illustrates several outcomes and responses based on input factors. The suggested technique establishes a polynomial connection between the input and the response. This example helps optimize the mix design to reduce the complexity of the testing procedure. These predictive models have proven beneficial for several applications. For instance41, proposed a predictive model for random fractures that encompasses two-dimensional issues and includes an experimental evaluation. However42, presented an alternative 3 d model for assessing substantial deformations and fractures that aids in the analysis of the existing experimental data in three dimensions. Generating statistical data necessitates pertinent experimental data that facilitates the alignment of model and test findings, hence aiding in evaluating the proposed model’s suitability. Design-Expert v11 is a quantitative software application that includes experimental designs, mathematical equations, analytical methodologies, and response optimization. The ANOVA analysis facilitates the examination of the connection and impact of the input data on the response45.

Results and discussion

This section presents the experimental results obtained from laboratory tests and analytical analysis. Different concrete mix design specimens tests were performed at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days. XRD and SEM analyses were also utilized to examine the concrete’s microstructural characteristics, which were conducted over 28 days. The correlation between curing age, fly ash (FA), rice husk (RH) as a cement replacement, fire clay (FC) as a sand substitute, and compressive strength was analyzed to understand the impact of these variables on the performance of concrete. These findings are discussed in detail below.

Compressive strength of the concrete

The compressive strength results for each mixture at different ages are shown in Fig. 5. The data reveal that the controlled mix (CS-0) exhibited compressive strengths of 10.22 MPa, 17.52 MPa, 22.82 MPa, and 28.2 MPa at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, respectively. The compressive strengths for the mixture with 8% FA, 8% RH cement, and 25% FC sand substitution (FC-FARH2) were 14.2 MPa, 22.7 MPa, and 31.4 MPa at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, respectively. This indicates an approximate 3% increase in compressive strength at 28 days compared to the control mix, suggesting an initial benefit of including fire clay and mineral admixtures at this substitution level. However, further increases in fire clay and mineral admixtures content reduced compressive strength. The FC-FARH3 mixture showed compressive strengths of 14.547 MPa, 18.477 MPa, and 22.89 MPa at 3, 7, and 28 days, respectively. FC-FARH4 mixture had compressive strengths of 13.1 MPa, 16.547 MPa, and 21.166 MPa at the respective ages.

Two factors are the primary causes of the increase in compressive strength, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The initial aspect is the physical effect of fire clay, which is primarily demonstrated by the fly ash and rice husk effect and particle filling effect. The value of fly ash is higher, indicating that its content of active ingredients is higher, and its particle size is approximately one-tenth that of cement. In comparison to the rice husk, its mixing is less efficient, and the heat of hydration is minimal. The basis for this variation in strength is that fly ash and rice husk are composed of spherical glass bodies of varying sizes with a smooth and dense surface. This surface can serve as a lubricant in the concrete, thereby enhancing the particle size gradation of cementitious materials. Agglomeration of cement particles can be prevented, and a portion of the free water can be released to enhance the fluidity of the cement by uniformly dispersing fly ash among the particles.

This facilitates the film’s adhesion to the cement particles, hence enhancing the integrity of the interior structure. The synergistic influence of fly ash activity and microaggregate effect resulted in the reaction of active aluminium trioxide in fly ash with the cement hydration product, calcium hydroxide, yielding hydrated calcium silicate and hydrated calcium aluminates. This process substituted the hexagonal plate-like calcium hydroxide, diminished the crystal content of concrete, enhanced the hardening of the cement paste, and facilitated the late-stage strength development of concrete9,10. The addition of fly ash and rice husk reduced the capillary porosity of fire clay concrete, thereby decreasing the number of macropores and increasing the number of micropores while enhancing the interfacial layer. This resulted in an improvement in the compressive strength of concrete.

These results indicate that while an 8% FA, 8% RH cement, and 25% FC sand substitution enhances compressive strength, higher substitution levels progressively decrease strength, underscoring the importance of optimizing fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content to balance mechanical performance and sustainability benefits. The 3D surface plot, shown in Fig. 6, illustrates the relationship between fly ash, rice husk, fire clay content, curing age, and compressive strength. The surface represents the variation in compressive strength with respect to the three independent variables: fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content, as well as curing age. The color gradient from red to yellow highlights changes in compressive strength, while the red dots mark the actual data points. These visualisations offer an intuitive understanding of how the content of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay, as well as the curing age, influences the compressive strength of concrete, supporting the optimisation of mix designs for enhanced performance.

Flexural strength of the concrete

Similar to the compressive strength tests, the controlled mix (CS-0) represented the standard concrete mixture with cement as the sole binder. In contrast, FC denoted mixtures containing varying proportions of fire clay as a partial substitute for sand and mineral admixtures as a partial substitute for cement by weight. Specifically, FA 0%, 4%, to 16%, RH 0%, 4%, to 16%, and FC 0%, 12%, to 50% indicated mixtures where the cement and sand content was replaced by weight, respectively. Figure 7 shows the flexural strength results for each mixture at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, as illustrated in the figure. The controlled mix (CS-0) exhibited flexural strengths of 0.918 MPa, 1.83 MPa, 2.62 MPa, and 2.87 MPa, serving as the baseline for comparison. For the mixture with 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, and 25% fire clay substitution (FC-FARH2), the flexural strength increased to 1.34 MPa, 2.32 MPa, 2.9 MPa, and 3.24 MPa, representing an improvement of approximately 3.05% compared to the control mix. This suggests that a moderate substitution level of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay can enhance the bending performance of the concrete.

Figure 7 illustrates that the incorporation of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay into concrete significantly enhances the properties of the transition zone at the interface between the paste and the aggregate. The energy required to disrupt the organic film is higher compared to the matrix without fly ash. Additionally, the concrete is interspersed with a substantial quantity of cementitious particles, resulting in increased friction during failure and enhanced toughness of the film. Consequently, the addition of fly ash and rice husk has a positive influence on the flexural strength of fire clay concrete. Consequently, a suitable amount of fly ash and rice husk enhances the flexural strength of fire clay concrete. The formation of stable bonds between the finer fly ash and the hydration products of the cement enhances the flexural strength of fire clay concrete. The calcium hydroxide produced during cement hydration cannot be entirely converted into hydrated calcium silicate gel, resulting in a decrease in the amount of hydrated calcium silicate gel in the concrete31. This will reduce the amount of hydrated calcium silicate gel in concrete and limit its ability to enhance the pore structure and fill voids. The inadequately reinforced interfacial zone results in decreased fracture resistance of fire clay concrete.

However, an increased content of fire clay and mineral admixtures further reduced flexural strength. The FC-FARH3 mixture had a flexural strength of 3.0 MPa, which, although higher than the control, was slightly lower than that of FC10. The FC-FARH4 and FC50 mixtures exhibited further reductions in flexural strength, with values of 2.21 MPa and 2.07 MPa, respectively. This declining trend suggests that the substitution of higher levels of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay compromises the concrete’s bending strength. These results highlight the importance of optimizing the level of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay substitution. While 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, and 25% fire clay substitution improve flexural strength, higher levels diminish returns and weaken the concrete’s bending capacity. This trend is consistent with the observed compressive strength results, where an optimal fire clay content was found to enhance mechanical properties, but excessive substitution reduced strength.

The 3 d surface plot shows in Fig. 8 the relationship between fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content, various ages, and flexural strength. The surface represents the variation in flexural strength with respect to the three independent variables: fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content, as well as curing age. The color gradient from red to yellow highlights changes in compressive strength, while the red dots mark the actual data points. These visualizations provide an intuitive understanding of how fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content and curing age influence the compressive strength of concrete, supporting the optimization of mix designs for enhanced performance. The insights gained from the flexural strength tests complement those obtained from compressive strength tests, providing a comprehensive understanding of the mechanical properties of concrete mixtures containing fire clay. By analysing compressive and flexural strength data, we can better evaluate the concrete’s overall structural performance and durability under various loading conditions.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The peaks in the XRD plots of mixtures with a higher fir clay content (FC-12% to 50%) are of lower strength than those of the control samples. This suggests that the availability of FC is reduced as a result of the replacement of FA and RH, which may be attributed to pozzolanic reactions29. The XRD confirms the presence of Friedel’s salts (chloride-binding phases) in FC 25% mixtures, as reported in30. These salts were also observed in the XRD, indicating effective chloride immobilisation. This could enhance the durability of concrete against chloride-induced corrosion. The XRD verifies the occurrence of C-S-H phases. The C-S-H remains intact across the mixtures, particularly in the 25% FC, 8% FA, and 8% RH replacement mixes, as indicated by the XRD peaks. This is linked to the liberation of confined water from ettringite and C-S-H.

The XRD analyses of the controlled mix, with fire clay 12% to 50% replacement sand, FA 4% to 16%, and RH 4% to 16% cement replacement before and after the acid attack reveal significant insights into the effects of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay on the cement matrix’s durability and chemical resistance. For the controlled mix without fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay replacement, Fig. 9a and b, the initial XRD pattern exhibits prominent peaks for Alite (C3S), Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C-S-H), and Portlandite (P), which are indicative of typical hydration products of Portland cement contributing to its structural strength. However, following an acid attack, there is a marked reduction in the intensity of these peaks, particularly Portlandite, reflecting its dissolution and the resultant degradation of the cement matrix, highlighting the susceptibility of conventional Portland cement to acidic conditions.

In contrast, the XRD pattern for the mix with 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, and 25% fire clay replacement, Fig. 10a Initial analysis shows peaks for Alite, C-S-H, and additional quartz (Q) from the fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay, indicating successful hydration and integration of fire clay into the cement matrix. Following the acid attack, although the peaks for Alite and C-S-H diminish, the persistence of quartz peaks indicates that the inclusion of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay enhances the cement’s resistance to acidic environments, thereby maintaining better durability compared to the controlled mix. This suggests that fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay mitigate some of the adverse effects of an acid attack by providing a more chemically stable phase.

For the mix with 8% fly ash, 16% rice husk, and 50% fire clay replacement, Figs. 10b and 11a and b, the initial XRD pattern displays dominant quartz peaks along with C-S-H and portlandite, reflecting the significant incorporation of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay into the mix. After the acid attack, while there is a notable reduction in the intensity of C-S-H and portlandite peaks, the quartz peaks remain prominent. This persistence indicates that a high content of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay significantly improves the acid resistance of the cement matrix, maintaining structural integrity despite acidic conditions. However, the reduced presence of traditional hydration products such as C-S-H suggests that mechanical properties may require further optimization while chemical resistance is enhanced.

significantly enhance the acid resistance of the cement matrix. While the controlled mix shows substantial degradation under acidic conditions, mixes 0% to 16% fly ash, 0% to 16% rice husk, and with 12% and 50% fire clay replacement retain more structural integrity due to the stability provided by quartz. The results suggest that fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay, especially at higher replacement levels, mitigate acid-induced deterioration, improving the durability of cementitious materials in harsh environments. However, achieving an optimal balance between mechanical strength and chemical resistance is essential, necessitating further investigation and optimization for practical applications. Overall, these findings demonstrate that incorporating fire clay as a partial replacement for cement can.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The formation of cementitious products within the concrete samples was revealed by microstructural analysis, which was conducted using scanning electron microscopy18, as illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13. The quantitative evaluation demonstrated the presence of unreacted cement, rice husk, and fly ash particles, with amorphous products adhering to the surfaces of the mineral admixture. The proportion of unreacted materials increased as the substitution of natural aggregates and fire clay alternatives increased, potentially as a result of reduced workability. This trend was due to the reduced mechanical properties depicted in Fig. 12. The overall nanostructure remained largely unaffected, exhibiting a dense C-S-H gel and portlandite platelets characteristic of hydration processes, despite the inclusion of fly ash and rice husk materials. The formation of C-S-H is supported by the stable calcium and silicon levels that were revealed by the elemental analysis (Figs. 12 and 13). Simultaneously, the presence of aluminum indicated the potential for the formation of C-S-H chain structures. These findings elucidate the complex interplay between FC, FA, and RH material incorporation, microstructural development, and resultant concrete properties24,28.

The SEM analyses of mixes with 12% to 50% fire clay replacement sand, 4% to 16% FA, and 4% to 16% RH cement replacement, both before and after the acid attack, provide detailed insights into the microstructural modifications and the resulting acid resistance imparted by the fire clay. For the mix with 25% fire clay, fly ash 8%, and rice husk 8% replacement, Fig. 12, the SEM image before the acid attack reveals a dense and compact microstructure characterized by well-formed hydration products, notably an amorphous and fibrous network of Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C-S-H) gel, and visible unreacted fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay particles. These unreacted particles enhance the matrix’s overall stability and packing density, enhancing mechanical properties. After an acid attack, the microstructure exhibits considerable degradation, as evidenced by increased porosity, a disrupted and less fibrous C-S-H gel structure, and microcrack formation. The dissolution of Portlandite and other hydration products is visible, yet remnants of fire clay particles persist, indicating partial resistance to acid-induced damage.

Figure 13. Initially, it exhibits a highly compact and stable microstructure with extensive integration of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay particles. These particles enhance the overall packing density and contribute to the formation of additional C-S-H through pozzolanic reactions, thereby improving durability and mechanical strength. Before the acid attack, the SEM image reveals a less prominent but still significant presence of C-S-H gel, alongside well-dispersed fire clay particles. However, after an acid attack, the microstructure undergoes substantial changes, displaying increased porosity, fragmentation, and a notable reduction in the C-S-H gel’s fibrous characteristics. The matrix exhibits micro-cracks and voids, indicative of a significant chemical attack. Despite this, the discernible fire clay particles suggest that the high fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay content imparts better resistance to complete degradation compared to the lower replacement level.

These observations are consistent with the XRD and SEM results, which indicate retained quartz peaks and reduced but persistent hydration products after acid attack. The findings highlight that while fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay enhance the acid resistance and durability of the cement matrix, particularly at higher replacement levels, significant damage still occurs under acidic conditions. The fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay particles provide a degree of chemical stability, reducing the overall degradation rate. However, optimizing the balance between mechanical strength and chemical resistance remains crucial. These results highlight the potential of using fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay as partial cement replacements to enhance the performance of cementitious materials in acidic environments, while also indicating the need for further research to optimise the material’s effectiveness in striking a balance between durability and mechanical integrity.

ANOVA analysis

This study examines the influence of three composite variables on the strength of concrete (A), specifically a combination of 8% fly ash (B), 8% rice husk (C), and 25% fine aggregate (D). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was previously used to evaluate the model’s significance. The statistical analysis reveals little variation (p-value of 0.0003) in the model’s compressive strengths, which were recorded at 31.6 MPa. Table 7 suggests that the samples had flexural strengths of 3.2 MPa, demonstrating an insignificant difference with a p-value of 0.0004. A low p-value, indicating statistical significance, demonstrates that the model is suitable and relevant. The tabulated findings suggest that all models seem to be statistically significant. The probability that noise will affect the model’s p-value is 0.0003. Models with F-values below 30.17, 5.61, and 7.49 are deemed important. The results are shown in Table 7. To assess the models’ robustness, the coefficient of determination (R-squared or R2) must be maintained within the range of 0.8824 to 0.9904. The corrected R² and forecasted R² variances for both models are below 0.1. This indicates that the modified R² and the projected R² are very congruent. The assessment of the signal-one-way ratio is considered essential for attaining optimum accuracy. Table 7 suggests that each model is capable of traversing the design space. A two-dimensional contour plot is produced from a three-dimensional surface diagram to validate a model. Prior studies indicate that projected values exhibit greater accuracy when data points are in proximity to the normal line44. The model’s validity and ability to determine suitable extraction parameters based on response outcomes are assessed by normal residual plots.

Optimization and experimental validation

The validation combination design results from numerous responses of RSM optimization techniques. This solution presents four alternatives for augmenting mechanical strength and response. Select the two-way ANOVA that maximizes the degree of agreement with your criteria. The RSM method is used for experimental verification. Standard scatter plots are used to evaluate the model’s performance and identify the optimal extraction parameters based on the responses. For convenience, the experimental and RSM results are succinctly presented in Tables 8 and 9. The compressive strength was recorded as 31.6 MPa, and the flexural strength as 3.2 MPa.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate the use of fire clay as a partial substitute for sand, fly ash, and rice husk in cement-based concrete mixes, aiming to improve sustainability, cost, and mechanical and microstructural properties, while uncovering essential insights and potential trade-offs. Fly ash, rice husk, and Fire clay offer sustainability and cost-effectiveness as partial substitutes for cement and sand. However, optimal substitution levels are crucial to balance these benefits with the desired concrete mechanical properties. Here are the key findings and considerations:

-

Compressive and flexural strength tests reveal a consistent decrease in strength with increased percentages of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay, highlighting a potential compromise between sustainability and mechanical performance.

-

For the mixture with 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, and 25% fire clay substitution, the flexural strength increased to 1.34 MPa, 2.32 MPa, 2.9 MPa, and 3.24 MPa at 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, and 28 days, respectively, representing an improvement of approximately 3.05% compared to the control mix.

-

The concrete maintains compressive strength comparable to the control mixture at an 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, partial cement, and 25% partial sand substitution level, fire Clay, suggesting that moderate substitution effectively balances sustainability and performance.

-

X-ray diffraction shows changes in the crystalline phases of the cement matrix due to fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay substitution, while scanning electron microscopy indicates enhanced packing density and stability pre-acid attack but increased porosity post-exposure.

-

Mixes with 8% fly ash, 8% rice husk, partial cement, and a 25% partial sand substitution level exhibit improved structural integrity and acid resistance, with prominent quartz peaks evident after the acid attack.

-

The present study employed a two-way ANOVA, ensuring the model’s significance level was below 0.001. It was determined that the residual error, caused by both lack of fit and pure error, was negligible. The predictive model accurately captures the relationship between the variables and the response.

Continued studies are essential to optimize the substitution levels of fly ash, rice husk, and fire clay, and to thoroughly assess the long-term durability and performance of concrete mixtures incorporating these materials. Ongoing research is crucial to enhance our understanding of how fire clay affects concrete properties, including mechanical performance, chemical resistance, and microstructural integrity. Such investigations will contribute to the development of more sustainable construction materials, aligning with both environmental and economic goals.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ridengaoqier, E., Hatanaka, S., Palamy, P. & Kurita, S. Experimental study on the porosity evaluation of pervious concrete by using ultrasonic wave testing on surfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 300, 123959 (2021).

Akbar, M., Hussain, Z., Huali, P., Imran, M. & Thomas, B. S. Impact of waste crumb rubber on concrete performance incorporating silica fume and fly Ash to make a sustainable low-carbon concrete. Struct. Eng. Mech. 85 (2), 000 (2023).

Chen, J. S. & Yang, C. H. Porous asphalt concrete: A review of design, construction, performance and maintenance. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 13, 601–612 (2020).

Louise, K. T. & TurnerFrank, G. C. Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 e) emissions: a comparison between geopolymer and OPC cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 43, 125–130 (2013).

Part, W. K., Ramli, M. & Cheah, C. B. An overview on the influence of various factors on the properties of geopolymer concrete derived from industrial by-products. Constr. Build. Mater. 77, 370–395 (2015).

Umar, T. et al. An experimental study on non-destructive evaluation of the mechanical characteristics of a sustainable concrete incorporating industrial waste. Materials 15 (20), 7346 (2022).

Akbar, M., Umar, T., Hussain, Z., Pan, H. & Ou, G. Effect of human hair fibers on the performance of concrete incorporating high dosage of silica fume. Appl. Sci. 13 (1), 124 (2022).

Fernando, S. et al. Assessment of long term durability properties of blended fly Ash-Rice husk Ash alkali activated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 369, 130449 (2023).

Somna, R., Saowapun, T., Somna, K. & Chindaprasirt, P. Rice husk Ash and fly Ash geopolymer Hollow block based on NaOH activated. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01092 (2022).

Steyn, Z. et al. Concrete containing waste recycled glass, plastic and rubber as sand replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 269, 121242 (2021).

Elinwa, A. U. & Mahmood, Y. A. Ash from timber waste as cement replacement material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 24 (2), 219–222 (2002).

Chowdhury, S., Mishra, M. & Suganya, O. The incorporation of wood waste Ash as a partial cement replacement material for making structural grade concrete: an overview. Ain Shams Eng. J. 6 (2), 429–437 (2015).

de Azevedo, A. R. et al. Effect of the addition and processing of glass Polishing waste on the durability of geopolymer mortars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15, e00662 (2021).

Usman, M. et al. Eco-friendly self-compacting cement pastes incorporating wood waste as cement replacement: A feasibility study. J. Clean. Prod. 190, 679–688 (2018).

Torkaman, J., Ashori, A. & Momtazi, A. S. Using wood fiber waste, rice husk ash, and limestone powder waste as cement replacement materials for lightweight concrete blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 50, 432–436 (2014).

Hesami, S. et al. Mechanical properties of roller compacted concrete pavement containing coal waste and limestone powder as partial cement replacements. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 625–636 (2016).

Alani, A. A. et al. Demolition waste potential for completely cement-free binders. Materials 15 (17), 6018 (2022).

Barreto, E. et al. Clay ceramic waste as Pozzolan constituent in cement for structural concrete. Maters 14 (11), 2917 (2021).

Zaheer, M. M. & Tabish, M. The durability of concrete made up of sugar cane Bagasse Ash (SCBA) as a partial replacement of cement: a review. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48 (4), 4195–4225 (2023).

Ali, A. et al. Influence of marble powder and polypropylene fibers on the strength and durability properties of Self-Compacting concrete (SCC). Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022 (1), 9553382 (2022).

Samadi, M. et al. Properties of mortar containing ceramic powder waste as cement replacement. Jurnal Teknologi (Sciences & Engineering), 77(12). https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v77.6315 (2015).

Özkılıç, Y. O. et al. Mechanical behavior in terms of shear and bending performance of reinforced concrete beam using waste fire clay as replacement of aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e02104 (2023).

Akbar, M., Hussain, Z., Imran, M., Bhatti, S. & Anees, M. Concrete matrix based on marble powder, waste glass sludge, and crumb rubber: pathways towards sustainable concrete. Front. Mater. 10, 1329386. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2023.1329386 (2024).

Lingling, X. et al. Study on fired bricks with replacing clay with fly Ash in high volume ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 19 (3), 243–247 (2005).

Samadi, M. et al. Waste ceramic as low-cost and eco-friendly materials in the production of sustainable mortars. J. Clean. Prod. 266, 121825 (2020).

Zeybek, Ö. et al. Performance evaluation of fibre-reinforced concrete produced with steel fibres extracted from the waste tyre. Front. Mater. 9, 1057128 (2022).

Martínez-García, R. et al. The present state of the use of waste wood Ash as an eco-efficient construction material: A review. Materials 15 (15), 5349 (2022).

Basaran, B. et al. Effects of waste powder, fine and coarse marble aggregates on concrete compressive strength. Sustainability 14 (21), 14388 (2022).

Zeybek, Ö. et al. Influence of replacing cement with waste glass on mechanical properties of concrete. Materials 15 (21), 7513 (2022).

Karalar, M. et al. Use of recycled coal bottom Ash in reinforced concrete beams as a replacement for aggregate. Front. Mater. 9, 1064604 (2022).

Yavuz, D., Akbulut, Z. F. & Guler, S. An experimental investigation of hydraulic and early and later-age mechanical properties of eco-friendly porous concrete containing waste glass powder and fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 418, 135312 (2024).

Ahmad, J. et al. Characteristics of sustainable concrete with partial substitutions of glass waste as a binder material. Int. J. Concrete Struct. Mater. 16 (1), 21 (2022).

İssi, A. et al. Casting and sintering of a sanitaryware body containing fine fire clay (FFC). J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 53, 157–162 (2017).

Joyklad, P., Nawaz, A. & Hussain, Q. Effect of fired clay brick aggregates on mechanical properties of concrete. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol., 25 (4), 42–62 (2018).

Miah, M. J. et al. Enhancement of mechanical properties and porosity of concrete using steel slag coarse aggregate. Materials 13 (12), 2865 (2020).

Zheng, C. et al. Mechanical properties of recycled concrete with demolished waste concrete aggregate and clay brick aggregate. Results Phys. 9, 1317–1322 (2018).

Hafez, R. D. A., Tayeh, B. A., Abd-Al, R. O. & Ftah Developing and evaluating green fired clay bricks using industrial and agricultural wastes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01391 (2022).

Muñoz, P. et al. Fired clay bricks made by adding wastes: Assessment of the impact on physical, mechanical and thermal properties. (2016).

Zhang, Y., Sun, Q. & Geng, J. Microstructural characterization of limestone exposed to heat with XRD, SEM and TG-DSC. Mater. Charact. 134, 285–295 (2017).

Akbulut, Z. F. Enhancement of cement mortar’s resistance to hydrochloric acid using hybrid SST/DHST fibers and silica fume. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 29 (10), 1935–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2025.2472054 (2025).

Nasir, A., Butt, F. & Ahmad, F. Enhanced mechanical and axial resilience of recycled plastic aggregate concrete reinforced with silica fume and fibers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-024-01803-z (2025).

Ahmad, F. et al. (eds) (Chunhui) Effect of Metakaolin and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag on the Performance of Hybrid Fibre-Reinforced Magnesium Oxychloride Cement-Based Composites. Int J Civ Eng 23, 853–868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-025-01074-4

Ahmad, Farhan, S., Rawat, R. C., Yang, L., Zhang & Zhang, Y. X. Fire resistance and thermal performance of hybrid fibre-reinforced magnesium oxychloride cement-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 472, 140867 (2025).

Leming, M. L. & Nguyen, B. Q. Limits on alkali content in cement—results from a field study. Cement, Concrete, and Aggregates, 22(1): pp. 41–47. (2000).

Ali, M. et al. Central composite design application in the optimization of the effect of pumice stone on lightweight concrete properties using RSM. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01958 (2023).

The American Concrete Institute’s (ACI. ) Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Normal, Heavyweight, and Mass Concrete (ACI 211.1–91) as Found in their ACI Manual of Concrete Practice 2000, Part 1: Materials and General Properties of Concrete (1991).

ASTM Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM-C150/C150M (American Society for Testing and Materials, 2020).

Standard Test Method for. Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates., ASTM-C136/C136M-19, (2019).

Standard test method. for the compressive strength of concrete cylinder, ASTM-C39/C39M, (2020).

Taylor, H. F. Cement ChemistryVol. 2 (Thomas Telford, 1997).

Shayan, A., Diggins, R. & Ivanusec, I. Effectiveness of fly Ash in preventing deleterious expansion due to alkali-aggregate reaction in normal and steam-cured concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 26 (1), 153–164 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University for funding this research work through project number “DGSSR-2025-02-01028’’. The Author also extends their appreciation to the School of Naval Architecture & Ocean Engineering, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of graduate Studies and scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No; (DGSSR-2025-02-01028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptual and methodology: Muhammad Akbar, Wali Ullah, Heba Abdou, and Ahmed. M. Yosri. Data Collection and Resources: Jahangir Badar, Nejib Ghazouani, Atta Ullah. Validation, verification: Ahmed. M. Yosri, Muhammad Akbar, Mahmoud Elkady, and Heba Abdou. Writing: Wali Ullah, Ahmed M. Yosri, Muhammad Akbar, Mahmoud Elkady. Reviewing and Editing: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akbar, M., Abdou, H., Yosri, A.M. et al. An experimental and statistical investigation into the optimisation of eco-friendly concrete incorporating agricultural and industrial wastes. Sci Rep 15, 36119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23488-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23488-9