Abstract

Examining the composition of aerosols in Antarctic ice cores can provide insights into past atmospheric circulation. However, interpreting this data requires an understanding of the characteristics and variability of present-day aerosols over time. In 2019, we performed the first year-round, multiparametric optical characterisation of atmospheric aerosols at Concordia Station in East Antarctica using OPTAIR, a novel instrument based on the Single Particle Extinction and Scattering (SPES) technique. We compared this data with the chemical composition of PM10 samples collected at the site and with meteorological data. We also compared it with synchronous data from a LIDAR and a ceilometer operating at Concordia Station. Significant temporal irregularities were observed in the atmospheric aerosol load, with more than one-third of the particles being dry-deposited during brief air mass subsidence events (‘spikes’), which mainly occurred in winter. The aerosol particles detected during these events were primarily composed of sea salt. Their optical properties differ significantly depending on whether they originate from frost flowers or the open ocean. Due to the intermittent nature of aerosol advection to Antarctica and its radiative effect, we estimate that glaciological, time-integrated samples may lead to an overestimation of light extinction by a factor of 3.5 or more.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The EPICA-Dome C (EDC) drilling project1 provided the oldest ice core archive of climate and atmospheric conditions from the last 800,000 years on the central East Antarctic Plateau (Dome C), where the Concordia research station has been operating permanently since 2005. Improving our understanding of present-day processes related to the transport and deposition of terrestrial, marine, and biogenic aerosols in remote polar regions is essential for enhancing our comprehension of climatic feedback mechanisms and reconstructing past climate changes, as determined through the analysis of deep ice cores. Analysis of the EPICA-Dome C ice core and other glacio-chemical stratigraphies from central East Antarctica2,3,4 has revealed that glacial periods display much higher levels of marine and terrestrial aerosols than interglacial periods5,6. During glacial periods, Southern South America is known to be the major continental dust supplier to central East Antarctica6, while the question remains open for the Holocene and earlier interglacials7. The main source of marine aerosol in central East Antarctica is currently thought to be sea spray originating from open-water areas north of the sea ice edge, although the highly saline frost flowers forming on the surface of newly-formed sea ice also play a role5,8,9,10.

Atmospheric aerosols reaching the interior of Antarctica can provide information on the present and past activity from natural and anthropogenic sources, processes occurring in the troposphere, and prevailing long-range transport patterns. In addition, aerosols are among the key climate forcing factors11, making it essential to characterise their optical, physical, and chemical properties in order to constrain climate models12. The chemical composition of aerosols in central Antarctica and Dome C has been investigated in several studies, which revealed different dominant sources in winter and summer, as well as seasonal concentrations affected by changes in oceanic biological activity and atmospheric transport efficiency13,14. In their 2012 study, Udisti et al.15 found that the annual amount of sea salt aerosol originates from a few intense transport events that occur in winter and are related to particular synoptic conditions. Their main drivers are the weakening of the Polar High centre, including Dome C, which favours the advection of marine air masses, and the strengthening of zonal winds along the coasts of East Antarctica, which enhances sea spray production. Biogenic aerosols are the most abundant in summer. These fine particles are primarily composed of non-sea-salt sulphate (nss-SO₄²⁻) and methanesulfonic acid (MSA), both of which are of biogenic origin and related to Southern Ocean phytoplankton16,17. Coarser aerosols contain sea-salt components such as Na⁺ and Cl⁻; however, chloride tends to be depleted by heterogeneous reactions with acidic species like HNO₃ and H₂SO₄ during long-range transport. Nitrate and chloride are found in higher concentrations in surface snow than in aerosol particles, suggesting that these species are largely deposited in the gas phase as HNO₃ and HCl16,18,19,20. However, the optical properties of surface aerosols, such as single scattering albedo, absorption, and Ångström exponent21, remain less documented. To study the optical properties of each aerosol source, high-resolution measurements are necessary, as the sources are far from the central Antarctic plateau and transport processes are often intense but short-lived15,17.

In December 2018, a novel optical system (OPTAIR) was installed at Concordia Station to investigate the atmospheric transport of aerosols on the East Antarctic Plateau, focusing on their optical properties at a high time resolution. The instrument can operate continuously under extreme climatic conditions, detecting and characterising individual particles with sub-second resolution. This study documents the first year-round, single-particle record of the optical properties of aerosols at Concordia Station, Dome C, during the year 2019. Optical measurements are based on the Single Particle Extinction and Scattering (SPES) method22. This method has previously been applied to meltwater samples from ice cores23,24,25,26 and is designed to provide direct, real-time access to the aerosol optical properties required for radiative transfer computations of airborne aerosol particles27,28. SPES optical data provide information on the number concentration and optical properties of the aerosols detected at ground level in the Antarctic atmosphere over Dome C, offering new insights into present-day transport processes and helping to frame the interpretation of paleoclimatic archives. The layout and physical principle of the method are detailed in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S1) and the literature28. The following section introduces the physical observables measured by the instrument.

The results are compared with the main ion composition of atmospheric aerosol measured in PM10 samples, with synchronous data from LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging), and a Vaisala CL51 Ceilometer operating at Concordia Station. Meteorological data from the Concordia Automatic Weather Station (AWS) are also considered. The timing and pattern of aerosol transport, as well as its optical and microphysical characteristics are investigated, with a view to gaining a deeper understanding of glaciological and paleoclimatic data. In addition to the effects directly related to the radiative properties of aerosols, indirect effects such as cloud nucleation processes make a large contribution to the Earth’s radiative balance29. While this aspect is beyond the scope of this study, it is worth mentioning that it is particularly relevant in areas with low or variable aerosol concentrations30.

Optical observables

OPTAIR provides access to the following four independent parameters, which are measured simultaneously for every single particle: the extinction cross-section \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) and the dimensionless optical fluence measured at 0°, 45°, and 90°, i.e. \(\:F\left(0\right)\), \(\:F\left(45\right)\) and \(\:F\left(90\right)\), respectively. Fluence is defined as the intensity scattered within a unit solid angle, at a unit distance, and with a unit impinging intensity28. For convenience, three further model-independent parameters can be derived: the ratios \(\:P\left(\theta\:\right)=\:F\left(\theta\:\right)/{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) at 0°, 45°, and 90°, which are equal the corresponding phase function values multiplied by the single scattering albedo (SSA)31,32. It is then possible to analyse and compare the particle properties in terms of these ratios, thereby minimising the effect of size. From these independent quantities, we derive the aerosol number-size distribution by inverting \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) and \(\:F\left(90\right)\) using Mie theory. The grain size indicator obtained by inverting the optical data is the only model-dependent parameter in this work and is a key indicator of transport that occurs in paleoclimate research14,23. We define \(\:r\) as the ratio between the two size estimates obtained for each particle from \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) and \(\:F\left(90\right)\). Deviations from the value\(\:\:r=1\) indicate deviations from the spherical model for particle sizing and can be used as a proxy for particle non-sphericity (see Fig. S4 and its related section in the Supplementary Information). Therefore, one could attempt an ad hoc modelling of non-spherical particles based on this information to estimate optical parameters such as the SSA, mass extinction efficiency (MEE), and asymmetry parameter. A similar approach was adopted in a former study to estimate the effects of shape23. Once the numerical density of the scatterers is known, the MEE of the particle population can be estimated from the direct measurement of \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\). In addition to the optical data, the absolute counts of aerosols provided by the instrument are proportional to their concentration at ground level. Each particle is associated with a unique sub-second timestamp. However, the extremely low atmospheric aerosol load at the site makes it preferable to integrate data daily to obtain sufficient statistics for the histograms. When particle counts are sufficient, the time resolution can be increased to a few minutes to gain greater insight into the dynamics of short-lived events. A list of the definitions of acronyms and symbols used in this manuscript can be found in Table SII in the Supplementary Information.

Data series and data variability

The optical aerosol data series obtained from SPES air measurements for the 2019 meteorological year encompasses 298 days (see Fig. 1) and covers the following months:

-

Summer: January and February.

-

Autumn: March, April, and May.

-

Winter: June, July, and August.

-

Spring: September and November.

Data for October were missing due to a power supply fault, which prevented data acquisition between days 263 and 299. December was excluded from the data analysis as it forms part of the 2019–2020 meteorological summer. Moreover, the increased activity at the station introduces considerable local contamination, so it was used for instrument maintenance. Other criteria were adopted to isolate possible data contamination, and our discussion is focused on the clean data series obtained after this control procedure. We removed days with wind provenance from 35°–90° and wind speeds over 2 m/s, as these conditions typically bring contamination from the Concordia Station33. However, this sector is also less often the source of winds. The location of the laboratory, which hosts many instruments, was chosen in order to minimise the likelihood of being downwind of the station power plant plume in prevailing local wind conditions. Additional checks revealed a few pollution events that occurred with no wind; these were also discarded from the dataset (see Fig. S5, Supplementary Information).

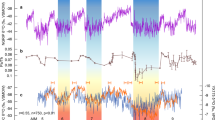

The histograms show the number of aerosol particles per day and the concentration of chemical species in PM10 per day: (a) the cumulative number of particles per day; (b) sea salt sodium; (c) non-sea salt sulphate; (d) methanesulfonic acid; (e) MSA calcium; (f) nitrate. Values of plotted variables that exceed the scale are reported in black close to their respective peaks. The orange horizontal line in panel (a) indicates the average value of 22, while the black dotted line indicates the threshold separating spike events from background levels. Spike events are highlighted with red solid lines in each panel and correspond to 2, 15 and 24 June; 10 July; and 6 and 20 August (from left to right). Dashed red lines indicate two days when counts were high, but the data had to be excluded from the analysis: 27 May and 12 August. Grey hatched areas indicate time intervals when SPES data was missing or discarded due to the wind coming from the base. Blue dotted lines indicate days on which the chemical data reported in each panel was missing.

Figure 1a shows the cumulative number of particles per day, \(\:{N}_\mathrm{C}\). The other panels (b–f) show a selection of chemical tracers used to associate aerosol sources with the counted particles34,35,36,37,38: sea spray, biogenic processes, crustal processes and atmospheric photochemistry: ssNa+, nssSO42−, MSA, nssCa2+ and NO3−. Values that exceed the scale, such as the two spike events in June 2019, are reported next to their corresponding peaks. The sea salt (ss) and non-sea salt (nss) fractions of Na+, Ca2+, and SO42- were calculated as described in Udisti et al.15. The general annual patterns of the chemical tracers reflect those previously observed and reported in the literature13,16,17. We observed maximum values for the biogenic aerosol tracers (nssSO4 and MSA), the winter spike for sea salt aerosol (i.e. ssNa)15,16, and a maximum concentration for NO3−34 in November. As a tracer of dust transport, the nssCa²⁺ concentration is low and characterised by narrow peaks distributed throughout the year (Fig. 1e). The number of counts per day as a monthly average is shown in Fig. S3 of the Supplementary Information.

In the \(\:{N}_\mathrm{C}\) series, counts are less than 10 about 29% of the time and between 10 and 100 about 65% of the time. Occasional large excursions emerging from the background can be observed, all of which have a lifespan ranging from several hours to several days. A threshold of 100 counts per day was chosen (orange line) to select days when the counts exceed the average value of 22 counts per day (black solid line) by three standard deviations (28/day). These are referred to as aerosol ‘spikes’ and the corresponding data are grouped into a subset labelled ‘S’. The complementary background data obtained from the rest of the record are labelled group ‘N’ (non-spikes). The average daily particle counts peak in late summer and autumn (centred around March) and in August, with minimums in January, May and November. Finally, when considering all the particles detected in 2019 as a whole (the cumulative case ‘C’), the monthly variability of the signal is dominated by the two main peaks occurring on 2 and 24 June, which determine the maximum counts.

The 2019 record shows a set of 6 spike events (corresponding to 16 days) that occurred between June and August, none of which occurred alongside surface wind from the station. These events accounted for 38% of the total particle counts over the measurement period, yet they occurred over just 6% of the measurement time (or 4% over the course of a year) and almost exclusively during the polar night. The minor SPES spike on 27 May could not be considered because the aerosol sampler for the chemical analysis failed on that day. Another minor SPES spike on 12 August was also discarded because its chemical signature suggested it might be contaminated. Data corresponding to days with wind coming from the station, not included here, are discussed in the Supplementary Material (see Figs S5 and S6), along with the case of 12 August (Fig. S7).

The large number of particles recorded during the spikes implies that they can be compared with the background despite their integration time being much shorter. Furthermore, by cross-checking optical (OPTAIR) and chemical (PM10) data, we can identify SPES spike events that correspond to spikes in ssNa+ concentration. Increased concentrations of oxidised sulphur and nitrate aerosols in summer are not evident in the SPES data. This could be due the heated section of the inlet meant to remove water and ice from the incoming particles. While light-scattering data from dry particles are less prone to misinterpretation compared to mixed-phase or coated aerosols, this process also hinders the detection of non-solid particulate.

In addition to sea salt aerosol, OPTAIR can also detect crustal aerosol, despite its extremely low concentration in the atmosphere. The instrument’s particle-by-particle operating principle ensures that no lower concentration limit is imposed. Regarding sea salt aerosol, Fig. 1c shows that most spikes in OPTAIR data coincide with negative values of nssSO42− at the time of ssNa + and SPES maxima. This feature is evident when the SO42−/Na+ ratio in seawater (0.25 w/w) is used to calculate the nssSO415,16,19,20 and it suggests a contribution from frost flowers from newly-formed sea ice around Antarctica. Frost flowers are crystalline icy structures in which the SO42−/Na+ ratio is lower than that of open-ocean sea salt due to the precipitation of mirabilite (Na2SO4 ·10H2O)) during their formation9,10,35. Their presence in the central Antarctic plateau during winter has been reported previously, although their overall contribution to sea salt aerosol remains poorly quantified.

More recent studies demonstrate that blowing snow deposited on sea ice is likely the dominant source of wintertime sea salt aerosol, though frost flowers cannot be entirely ruled out39,40. Frost flowers may also contribute indirectly to sea salt aerosol emissions by salinating wind-blown snow41. Wind-blown snow has SO42−/Na+ ratios similar to those of frost flower, therefore, sea salt aerosols can arise by sea-ice areas through erosion of saline snow on sea-ice by strong winds and by sublimation of snow particles42,43,44.

It has been demonstrated that sea salt aerosol produced in the Arctic in winter from blowing snow accounts for about 30% of the total particle number, and that sea salt aerosol can increase the longwave emissivity of clouds, leading to a calculated surface warming of + 2.30 W m−2 under cloudy sky conditions40. Understanding the link between sea salt aerosol (from both frost flowers and wind-blown snow) and sea ice is crucial for paleoclimate studies that aim to reconstruct past sea-ice extent around Antarctica.

Distributions of optical parameters during 2019, classified by month: (a) \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) (µm2), (b) diameter \(\:d\) (µm) of aerosol number size distribution obtained by inverting \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) data, (c) \(\:P\left(0\right)\), and (d) \(\:P\left(90\right)\). Solid circles represent the median of the distributions, while upper and lower lines indicate the limits containing 67% of the distributions.

Figure 2 shows the monthly variability of the SPES optical parameters from the entire data series (including spikes). A similar representation of the data series excluding spike events can be found in Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Information. The median M of the distributions is indicated by solid circles, while the upper and lower lines indicate the interval containing 67% of each lognormal distribution. This interval is obtained as \(\:M\cdot\:G\) and \(\:M/G\) respectively, where \(\:G\) is the geometric standard deviation. Although our data do not cover the whole of 2019, the data suggest that the winter months were characterised by lower \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) compared to summer (\(\:-55\%\), Fig. 2a), which can be partly ascribed to aerosol size.

Figure 2b shows the distributions of the equivalent diameters calculated from \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) using Mie theory, i.e. the diameter of spheres with the same extinction cross-section, by setting the refractive index to \(\:m=1.54+\text{i}{\cdot10}^{-3}\)36,37. The size distributions generally showed finer aerosol particles in winter than in summer, with a size difference of around 20%. Plots of \(\:P\left(0\right)\) and \(\:P\left(90\right)\) (see Fig. 2c and d) were obtained from the monthly changes in the histograms describing the optical properties of the particles. Similar to \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\), \(\:P\left(0\right)\) exhibits an expected high seasonal variability that increases by up to + 40% in winter compared with summer Changes in \(\:P\left(90\right)\) are less noticeable (< 25% approximately). We note that \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) decreases when \(\:P\left(0\right)\) increases. Moreover, a slight skewness can be noticed in the histograms (\(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) in winter, for example); we stress that during wintertime the lognormal curves for \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) shrink markedly. Finally, we observe that the main changes in \(\:P\left(90\right)\) are not correlated with those in \(\:P\left(0\right)\) and that the widths of the corresponding distributions are almost constant in time.

Aerosol transport and meteorological conditions

Comparison of OPTAIR aerosol counts and meteorological data. (a) Time series of attenuated backscatter profiles sampled by IAMCO (Italian Antarctic Meteo-Climatological Observatory) Vaisala CL51 Ceilometer (filled contour, bottom and left scales). The black line represents the time series of OPTAIR counts on an hourly basis; regions shown in white correspond to missing values. The coloured line above shows the cloud cover as calculated by the Vaisala CL51 Sky Condition algorithm (clear sky/few clouds in light cyan, scattered in dark green, broken in red and overcast in black). (b) Time series of ECMWF ERA5 Vertical Velocity (filled contour) and ECMWF ERA5 Total Precipitation (blue lines). The coloured line shows Wind Direction between 0° and 120° (dark violet), between 150° and 240° (gold), and between 270° and 330° (violet), corresponding to subset associated to the major events revealed by SPES. Wind measurements at a height of 3 m were obtained from the AWS (operated by IAMCO). Green dashed lines highlight the aerosol spikes revealed by SPES.

Figure 3 shows a comparison of OPTAIR aerosol counts and attenuated backscatter profiles from the Vaisala CL51 ceilometer (Fig. 3a), as well as ECMWF total precipitation data and vertical wind velocity (Fig. 3b), between April and September, when the majority of aerosol spikes occurred. There is no clear relationship between precipitation/backscatter values from the ceilometer and aerosol counts. However, comparing aerosol counts with vertical wind velocities (see Figs. 4b and 5) reveals that the majority of aerosol spikes are associated with tropospheric air mass subsidence (positive vertical wind velocity) from above, with the wind predominantly blowing from the south-southwest (180–220°). This is the direction from which the highest percentage of winds that blow from the southern continental regions reach Dome C38,45. A wind rose histogram for 2019 is shown in Fig. S8 (Supplementary Information). We also note that some spike events occur in conjunction with a cloudy sky.

Back trajectory analysis of spike events (see the Appendix in the Supplementary Information) showed that, before arriving at Concordia, air masses follow the typical westerly wind flux spiralling over the southern hemisphere continents and the Antarctic Ocean, where extensive sea ice is still present at that time of year. Particles in both June 2019 events underwent this long-range atmospheric pathway, which enriched the air masses with sea salt aerosols. Although sea salt and mineral dust particles have a similar size distribution14, the timescales on which they arrive at the site differ due to their distance from sources. While sea salt sources are close by, it takes dust particles an average of at least two weeks to travel to Dome C46. In any case, air masses must also be considered when analysing distributions.

Detail of the LIDAR time series compared to OPTAIR counts for the two most prominent aerosol peaks of the series. (a) LIDAR (top panel) backscattered depolarised data and OPTAIR (bottom panel) counts for days 152 (1 June) and 153 (2 June). (b) Same as in (a), showing the days around the spike event affecting 24 June.

In this instance, we analysed OPTAIR aerosol counts obtained with a resolution of 10 min without selecting events, thus treating the data as equivalent to a traditional counter. The counts were compared with meteorological data and with simultaneous, independent measurements from the Concordia backscatter LIDAR instrument. This allowed us to detect backscattered depolarised light from aerosols at heights between 10 m and 7000 m above ground level. Further information about the instrument can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Two case studies, corresponding to the two days with the highest aerosol levels of the year, were selected for comparison with LIDAR data (panels a and b in Fig. 4). The first event corresponds to the prominent peak on 2 June (day 153, Fig. 1), while the second case relates to 23–27 June (Fig. 4b). In the first case, an episode of precipitation occurred on 1 June (day 152) during which no aerosol values above background levels were recorded. This was followed by an exceptional event characterised by spiking aerosol counts, which lasted for around 10 h from the early hours of day 153. LIDAR backscattered depolarised data acquired during this peak show a prominent plume at an altitude of approximately 800 m above ground level at Concordia (light blue shadow Fig. 4a). The same was observed for the second event in late June. This event was much longer, spanning approximately two days and peaking in the afternoon/evening of 24 June (day 174). At this time, the LIDAR data revealed a plume in the troposphere above Concordia (below 1000 m). Both aerosol peaks were related to dry atmospheric conditions (i.e. no precipitation) and the descent of an aerosol-rich plume from above. Chemical data indicate that these two events correspond with the transport of aged sea salt aerosol containing NaCl, NaHSO4, NaNO3, and NaM. Most of the initial NaCl in sea-salt particles reacts with HNO3, H2SO4, or MSA in the atmosphere before reaching Dome C47. A specific feature of these particles is the depletion in SO42− (see Fig. 1), thereby resembling fractionated sea-salt aerosols from sea ice sources (frost flower or wind blow snow). Indeed, aerosols can be lifted from the sea ice surface and entrained to the free troposphere (up to 4 km) through vertical motion by cyclonic activity until reaching the interior of Antarctica46. In addition to these two major events, we investigated the relationship between aerosol spikes and the air mass subsidence recorded at Concordia.

OPTAIR winter aerosol peaks and meteorological data versus wind direction (2019). (a) Cumulative number of events (%) with above-average counts (\(\:{N}_{\text{C}}>22\)) occurring within wind direction intervals of 10° each, in the period 31 March–1 September (\(\:{N}_{\text{e}\text{v}\text{e}\text{n}\text{t}\text{s}}\), blue line). Average values of specific humidity (AWS Q, orange line) and wind speed (AWS WS, red line) for events with \(\:{N}_{\text{C}}>22\) counts occurring within specific wind direction intervals of 10° each. (b) Average profiles of ECMWF ERA 5 vertical velocity (contour plot, positive for downward velocity, red, and negative for upward, blue) and cumulative value ECMWF ERA 5 total precipitation for events with \(\:{N}_\mathrm{C}>22\) counts occurring within specific wind direction intervals of 10° each (ECMWF TP, green line).

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between above-average aerosol concentrations during the winter months of 2019 (April–September) and meteorological data pertinent to the transport of aerosol particles, such as air mass humidity, wind direction and speed, vertical wind velocity, and precipitation. Here, we extend our analysis to days when \(\:{N}_{\text{C}}\), the total count over 24 h, exceeds the average value of 22 counts per day, within wind direction intervals of 10° each. These events are not limited to aerosol spike events and account for around 70% of all the sampled particles. For the sake of conciseness, we discuss the outcomes in terms of wind directions subdivided into three main intervals. The blue curve in panel a) shows how often the counts were above the threshold, which occurred primarily when wind came from 120–240° (10%), and secondarily from 240–360° (3%), and 0–120° (5%). Regarding the counts themselves (black curve), approximately 33% of particle registrations occurred within the 120–240° range, 20% within the 240–360° range and 16% within the 0°–120° range. The highest peaks during winter are associated with the 120–240° interval, but we note that part of the large peak on 2 June exceeding 1000 counts per day (see Fig. 1a) falls within the 240–360° interval. These exceptional counts exceed the maximum of any measurement during the period by more than a factor of four and establish alone the number of particles within the 240–360° range.

The air masses from 120–240° are characterised by very low humidity; aerosol advection within this range is associated with a lack of precipitation, and an average wind speed that is slightly higher than in the other two subsets (see Fig. 5a). Furthermore, the vertical wind velocity profile (5b) shows a tendency for air masses to move downwards (positive values), which is more accentuated in the lower layers between 0 and 4 km. This favours subsidence conditions, and thus the downward transport of aerosols. Conversely, winds coming from 0–120° are associated with moist air masses (or precipitation) on the Antarctic Plateau, possibly resulting in wet deposition of aerosol particles. According to ERA5 reanalysis models, almost all precipitation occurs when the wind direction is 0–120° (see Fig. 5a and b). During these events, the AWS recorded humidity values that were, on average, 5 times higher than in the range 120–240°. The model’s vertical velocity profile shows unusual negative values (upwards movement) between 1 and 6 km during the period under consideration (Fig. 3b), which are linked to the interaction of transient eddies with the Antarctic coastal slope and their inland propagation48. The 240–360°range exhibits many of the characteristics of the 120–240° range but with a reduced tendency towards subsidence conditions and lower average wind speeds, with fewer precipitation events occurring. A comparison of total counts and the number of cases shows that dry air masses efficiently transport aerosols to the site in winter.

Optical data and aerosol properties

In Fig. 6 we report the relative abundance of particles recorded as a function of \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) (horizontal axis) and \(\:P\left(0\right)\), \(\:P\left(45\right)\), and \(\:P\left(90\right)\) (vertical axes, black, red, and blue, respectively). The plots are two-dimensional histograms, where the colour intensity represents the relative number of particles for each two-dimensional bin28. For ease of comparison, we include the results of Mie theory for spheres with a refractive index of 1.33 (water) and 1.55, a representative value for aerosol particles49. In Fig. 6a and b we report the histograms for the open ocean (O) and frost flowers or wind-blown snow (F) sea salt, as inferred from chemical data (see Data series and data variability section). F events are characterised by a bimodal distribution for \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) between 1 and 3 µm2 along the vertical axis. Quantitatively, the separation between the two populations in Fig. 6b corresponds to a factor of 3–4. Almost half of the population observed during these events scatters light much more effectively at 90° than on other days. This high-scattering population appears as an additional component when the frost flowers are present9,47, while the population with \(\:P\left(90\right)<0.025\) is similar to the typical marine aerosols observed in panel a). We separate the two populations reported in Fig. 6b in panels c) and d), above and below the \(\:P\left(90\right)\) = 0.025 threshold, respectively.

Relative abundance of particles, recorded as a function of \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) (horizontal axis) and \(\:P\left(0\right)\), \(\:P\left(45\right)\), and \(\:P\left(90\right)\) (vertical axes: black, red, and blue, respectively). Plots are two-dimensional histograms; the colour intensity represents the relative number of particles. Panels refer to open ocean (a) and frost flowers (b) sea salt particles during the selected days (see text), while in (c) and (d) we represent the same data than in (b) by separating particles with \(\:P\left(90\right)<0.025\) and \(\:P\left(90\right)>0.025\). Mie theory for spheres with a refractive index of 1.33 (water) and 1.55 (aerosol particles) is shown with solid and dashed lines, respectively.

The main properties of the populations are summarised in Table 1. All quantities are averaged over the corresponding populations on a particle-by-particle basis. Size is the only physical property we infer from optical data and the only model-dependent parameter. Inverting scattering data, i.e. using scattering signals to infer properties such as size, requires a model that fits all the measured parameters50. Particles that deviate from the uniform spherical model exhibit differences and variability in radiative properties that hinder data interpretation without additional information26. However, the mild dependence of \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) on particle shape provides reliable size estimates51, although non-spherical shapes require more detailed analysis and datasets for each particle to invert scattering data. While the aerosol sizes estimated from \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) and \(\:F\left(90\right)\) differ, the two methods yield similar relative changes between spike and non-spike particles and monthly variabilities. Further details on the discrepancies between the sizes estimated from \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) and \(\:F\left(90\right)\) across the different data sets are provided in Table SI in the Supplementary Information.

The numerical estimators reported in Table 1 are very similar when moving from the O to the F population; however, the ratio r changes from 1.22 to 1.10. When comparing size distributions, the main differences can be observed between the winter sea salt-rich spikes and the summer–autumn period. The winter spikes (S) show the finest grain sizes, with an average diameter \(\:\langle\:d\rangle\:\) of 0.81 ± 0.02 μm, which is close to the value of 0.82 ± 0.02 μm calculated for the complementary winter background (NW). During summer and autumn (NA), the average diameter increases to 0.91 ± 0.02 μm, while the average diameter for background particles across all seasons is 0.89 μm. It is worth noting that these values are only slightly smaller than those found for sea salt and other atmospheric aerosols found in ice cores from sublimated ice samples52. Regardless of the interpretation model, the data highlight the variability in \(\:P\left(90\right)\) between S and NW data sets.

Despite the fact that the average \(\:P\left(90\right)\) is more than three times larger for the upper population, we find that none of the other quantities differ appreciably. We observe only a slightly smaller size from the smaller \(\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) distribution. The ratio r inherits the relevant increase in 90° scattered light, changing from 1.4 to 0.77. We point out that this is the only instance in which r is smaller than 1.

As discussed above, the composition of marine aerosols reaching Concordia depends on the initial chemical composition of salts, among other factors, which varies between open ocean and sea ice sources. Therefore, given the difference in the chemical composition of sea-salt particles derived from open ocean or sea ice sources and reaching Dome C, we can assume that the different optical responses of these two populations (open ocean-derived or sea ice-derived) might be due to the different morphology of salts particles. Further investigation could address this point. It could significantly affect estimates of the radiative effect of marine aerosols during past climatic periods.

In summary, the data show that, although there is no significant change in aerosol grain size between winter spikes (S) and the winter background (NW), there is a significant change in the optical properties of particles. Spike events (\(\:r\) = 1.08) are associated with generally more spherical aerosol particles than the complementary seasonal background (\(\:r\) = 1.17). More marked deviations from the uniform sphere emerge when comparing NW to NA (winter and summer background). Compared with winter, both the aerosol diameter and the non-sphericity parameter \(\:r\) both increase by around 10% in summer, when the atmosphere at Concordia is generally characterised by coarser and less spherical particles. Moreover, during the most prominent events populated by sea salt, the optical properties are significantly impacted by an additional population with \(\:r\) smaller than 1 (\(\:r\) = 0.77). This is capable of scattering over three times the other particles. We conclude that the optical characteristics of particles change appreciably with the season. In particular, winter aerosol particles, especially those transported during sea salt-rich aerosol events, exhibit different characteristics from those observed in summer and autumn. These changes can be attributed to changes in particle morphology related to the particles’ different natures. The radiative and paleoclimate implications of this behaviour of aerosol particle transport are discussed below.

Implications on radiative properties and conclusions

Several key points emerge from the 2019 data. Optical data indicate that a relevant fraction of the aerosol load in the Antarctic atmosphere occurred in the form of particle concentration spikes over a brief time interval. The relative statistical significance of these spike events suggests that it is unsafe to infer the radiative impact of aerosols from data that is not sufficiently time-resolved, i.e. with a resolution of at least one month. Due to their abrupt nature, concentration spikes only have a radiative impact for a short time. This also implies that the role of clouds is especially relevant, as they can completely negate the effect of spikes. In fact, the most prominent aerosol-rich events occurred during winter and therefore could not affect the transmission of solar radiation through the atmosphere. This feature cannot be captured by measuring multi-year samples as is often the case in the cumulative approaches used in glaciological studies, where temporal resolution is critical53,54,55. Generally, the aerosol population recorded in snow and ice cores differs from that detected in situ in real time, due to interaction with water and post-depositional processes20,24,56. Nevertheless, conclusions can be drawn about the climatic impact of aerosols in terms of the duration of spike events. The accuracy of interpreting ice core glaciological analyses, which typically span periods of over a year at sites with low accumulation, depends on their detection57,58. Similar considerations apply to estimates of aerosol radiative forcing in the Antarctic atmosphere in the past.

Based on our data, we estimate the impact of aerosols on the radiative properties of the atmosphere under reasonably ideal conditions of high transmission and a low cloud index. The overall effect of aerosols is overestimated by a factor of 3–5 in the glaciology-based cumulative case, which does not account for the lifetime of the events (C). It should be noted that cloud cover has not been considered in this estimate. To compare the optical response of the aerosol cloud we use the inverse extinction length, \(\:{\varLambda\:}^{-1}=n\:\langle\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\rangle\:\), where \(\:n\) indicates the number density of scatterers. The inverse extinction length is proportional to the optical depth of the particle cloud, and therefore to MEE. As a quantity proportional to the number density of scatterers MEE can be readily obtained by noting that, for any air flux through the measurement cell (in m3/s), it is simply proportional to the count rate \(\:{N}_{\text{C}}\), i.e., the number of counts accumulated during a given integration time. The OPTAIR instrument cannot provide an absolute estimate of the number concentration of aerosol particles in the atmosphere without a calibration procedure. As this is beyond the scope of this work, we evaluate an alternative quantity, a dimensionless concentration (\(\:\nu\:\)), defined as the ratio of the fraction of particles counted within a given subset (\(\:\phi\:\)) to the time fraction (\(\:\tau\:\)) during which they were collected (\(\:\nu\:=\phi\:/\tau\:\)). Consequently, \(\:\nu\:\) equals 1 when considering the entire dataset and might be greater than one.

Table 2 shows the results for the normalised concentrations, \(\:\nu\:\), the average cross-sections \(\:\langle\:{C}_{ext}\rangle\:\), and the resulting inverse extinction lengths \(\:{\varLambda\:}^{-1}=\nu\:\:\langle\:{C}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\rangle\:\). Despite the smaller scattering cross-section, the scattering length decreases during particle-rich spike events (S). This change occurs for two reasons: (1) there is a notable increase in particle number concentration during spikes and (2) spikes are brief events spanning a short period of time. To better clarify the impact of the event duration, Table 3 evaluates the same optical parameters without considering the occurrence time fraction (cumulative case, C), as with glaciological cumulative samples. This includes the same data as in the S + N case, but the occurrence time of aerosol particles with different optical properties in the atmosphere is neglected. This provides a quantitative estimate of the bias that time-related approximations can introduce. In particular, the overall effect of S particles is exaggerated in the cumulative C case with the overestimation of \(\:{\varLambda\:}^{-1}\) being approximately 3 times greater than in the real case (S + N).

We introduce a more realistic scenario by excluding particles arriving at Concordia when the Sun is below the horizon and therefore have no radiative effect. In terms of radiative balance, all the aerosol-rich events that occurred during the winter of 2019 are essentially irrelevant, so we can consider the radiative effects to be reasonably quantified by the N case (Table 2). The discrepancy becomes even larger when comparing the C case (\(\:{\varLambda\:}^{-1}\:\tau\:\) = 6.82), with the more realistic N case. Light extinction from the atmospheric aerosol load throughout the year is overestimated by a factor of between 3.5 and 5, depending on whether the S + N or N case is considered. These preliminary outcomes can be refined through future campaigns involving longer time series, as atmospheric aerosol transport has significant implications for glaciological studies that aim to assess past atmospheric radiative properties through the analysis of ice core archives.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to Marco A. C. Potenza or Llorenç Cremonesi. Data by the Antarctic Meteorological and Climatological Observatory are publicly available at www.climantartide.it/dataonline/aws/.

References

Augustin, L. et al. Eight glacial cycles from an Antarctic ice core. Nature 429, 623–628 (2004).

Lambert, F. et al. Dust-climate couplings over the past 800,000 years from the EPICA dome C ice core. Nature 452, 616 (2008).

Petit, J. R. et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999).

Dome Fuji Ice Core Project Members. State dependence of Climatic instability over the past 720,000 years from Antarctic ice cores and climate modeling. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600446 (2017).

Wolff, E. et al. Changes in environment over the last 800,000 years from chemical analysis of the EPICA dome C ice core. Q. Sci. Rev. 29, 285–295 (2010).

Delmonte, B. et al. Geographic provenance of aeolian dust in East Antarctica during pleistocene glaciations: preliminary results from Talos dome and comparison with East Antarctic and new Andean ice core data. Q. Sci. Rev. 29, 256–264 (2010).

Paleari, C. I. et al. Aeolian dust provenance in central East Antarctica during the holocene: environmental constraints from Single-Grain Raman spectroscopy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9968–9979 (2019).

Mulvaney, R. & Peel, D. A. Anions and cations in ice cores from Dolleman Island and the Palmer land Plateau, Antarctic Peninsula. Ann. Glaciol. 10, 121–125 (1988).

Rankin, A. M., Auld, V. & Wolff, E. W. Frost flowers as a source of fractionated sea salt aerosol in the Polar regions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 3469–3472 (2000).

Rankin, A. M., Wolff, E. W. & Martin, S. Frost flowers: Implications for tropospheric chemistry and ice core interpretation. J. Geophys. Res. D: Atmos.107, AAC 4-1-AAC 4–15 (2002).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution To the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

Albani, S. et al. Improved dust representation in the community atmosphere model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 541–570 (2014).

Becagli, S. et al. Biogenic aerosol in central East Antarctic plateau as a proxy for the ocean-atmosphere interaction in the Southern ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 810, 151285 (2022).

Oyabu, I. et al. Compositions of Dust and Sea Salts in the Dome C and Dome Fuji Ice Cores From Last Glacial Maximum to Early Holocene Based on Ice-Sublimation and Single-Particle Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. D: Atmos. 125, e2019JD032208 (2020).

Udisti, R. et al. Sea spray aerosol in central Antarctica. Present atmospheric behaviour and implications for paleoclimatic reconstructions. Atmos. Environ. 52, 109–120 (2012).

Legrand, M. et al. Year-round record of bulk and size-segregated aerosol composition in central Antarctica (Concordia site) – Part 2: biogenic sulfur (sulfate and methanesulfonate) aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 14055–14073 (2017).

Becagli, S. et al. Study of present-day sources and transport processes affecting oxidised sulphur compounds in atmospheric aerosols at dome C (Antarctica) from year-round sampling campaigns. Atmos. Environ. 52, 98–108 (2012).

Jourdain, B. et al. Year-round record of size-segregated aerosol composition in central Antarctica (Concordia station): implications for the degree of fractionation of sea-salt particles. J. Geophys. Res. D: Atmos.113, D14 (2008).

Udisti, R. et al. Atmosphere–snow interaction by a comparison between aerosol and uppermost snow-layers composition at dome C, East Antarctica. Ann. Glaciol. 39, 53–61 (2004).

Legrand, M. et al. Year-round records of bulk and size-segregated aerosol composition in central Antarctica (Concordia site) – Part 1: fractionation of sea-salt particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 14039–14054 (2017).

Virkkula, A. et al. Aerosol optical properties calculated from size distributions, filter samples and absorption photometer data at dome C, Antarctica, and their relationships with seasonal cycles of sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 5033–5069 (2022).

Potenza, M. A. C., Sanvito, T. & Pullia, A. Measuring the complex field scattered by single submicron particles. AIP Adv. 5, 117222 (2015).

Potenza, M. A. C. et al. Shape and size constraints on dust optical properties from the dome C ice core, Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 6, 28162 (2016).

Potenza, M. A. C. et al. Single-particle extinction and scattering method allows for detection and characterization of aggregates of aeolian dust grains in ice cores. ACS Earth Space Chem. 1, 261–269 (2017).

Simonsen, M. F. et al. East Greenland ice core dust record reveals timing of Greenland ice sheet advance and retreat. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Simonsen, M. F. et al. Particle shape accounts for instrumental discrepancy in ice core dust size distributions. Clim. Past. 14, 601–608 (2018).

Mayer, B. & Kylling, A. Technical note: the libradtran software package for radiative transfer calculations - description and examples of use. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5, 1855–1877 (2005).

Cremonesi, L. et al. Multiparametric optical characterization of airborne dust with single particle extinction and scattering. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 54, 353–366 (2020).

Dusek, U. et al. Size matters more than chemistry for cloud-nucleating ability of aerosol particles. Science 312, 1375–1378 (2006).

Mauritsen, T. et al. An Arctic CCN-limited cloud-aerosol regime. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 165–173 (2011).

Chandrasekhar, S. Radiative Transfer (Courier Corporation, 2013).

Cremonesi, L. in In Springer Series in Light Scattering: Volume 9: Electromagnetic Theory of Scattering and Radiative Transfer. 165–203 (eds Kokhanovsky, A.) (Springer International Publishing, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29601-7_3

Caiazzo, L. et al. High resolution chemical stratigraphies of atmospheric depositions from a 4 m depth snow pit at dome C (East Antarctica). Atmosphere 12, 909 (2021).

Traversi, R. et al. Insights on nitrate sources at dome C (East Antarctic Plateau) from multi-year aerosol and snow records. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 66, 22550 (2014).

Wagenbach, D. et al. Sea-salt aerosol in coastal Antarctic regions. J. Geophys. Res. D: Atmos. 103, 10961–10974 (1998).

Petzold, A. et al. Saharan dust absorption and refractive index from aircraft-based observations during SAMUM 2006. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 61, 118–130 (2009).

Kandler, K. et al. Chemical composition and complex refractive index of saharan mineral dust at Izaña, Tenerife (Spain) derived by electron microscopy. Atmos. Environ. 41, 8058–8074 (2007).

Argentini, S. et al. Observations of near surface wind speed, temperature and radiative budget at dome C, Antarctic plateau during 2005. Antarct. Sci. 26, 104–112 (2014).

Huang, J. & Jaeglé, L. Wintertime enhancements of sea salt aerosol in Polar regions consistent with a sea ice source from blowing snow. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 3699–3712 (2017).

Gong, X. et al. Arctic warming by abundant fine sea salt aerosols from blowing snow. Nat. Geosci. 16, 768–774 (2023).

Obbard, R. W., Roscoe, H. K., Wolff, E. W. & Atkinson, H. M. Frost flower surface area and chemistry as a function of salinity and temperature. J. Geophys. Res. D: Atmos. 114, D20 (2009).

Hara, K. et al. Important contributions of sea-salt aerosols to atmospheric bromine cycle in the Antarctic Coasts. Sci. Rep. 8, 13852 (2018).

Rhodes, R. H., Yang, X., Wolff, E. W., McConnell, J. R. & Frey, M. M. Sea ice as a source of sea salt aerosol to Greenland ice cores: a model-based study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9417–9433 (2017).

Osada, K. et al. Sulfate depletion in snow over sea ice near Syowa Station, Antarctica, in relation to the origin of sulfate depleted sea salt aerosol particles in winter. Polar Meteorol. Glaciology. 15, 21–31 (2001).

Genthon, C. et al. 10 years of temperature and wind observation on a 45 m tower at dome C, East Antarctic plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 13, 5731–5746 (2021).

Petit, J. R. & Delmonte, B. A model for large glacial–interglacial climate-induced changes in dust and sea salt concentrations in deep ice cores (central Antarctica): palaeoclimatic implications and prospects for refining ice core chronologies. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 61, 768–790 (2009).

Teinilä, K., Frey, A., Hillamo, R., Tülp, H. C. & Weller, R. A study of the sea-salt chemistry using size-segregated aerosol measurements at coastal Antarctic station neumayer. Atmos. Environ. 96, 11–19 (2014).

Wacker, U., Ries, H. & Schättler Ulrich. Flow across the Antarctic plateau. COSMO Newsl. 6, 213–219 (2006).

Jurányi, Z. & Weller, R. One year of aerosol refractive index measurement from a coastal Antarctic site. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 14417–14430 (2019).

Cremonesi, L. et al. Light extinction and scattering from aggregates composed of submicron particles. J. Nanopart. Res. 22, 1–17 (2020).

Berg, M. J., Sorensen, C. M. & Chakrabarti, A. Extinction and the optical theorem. Part I. Single particles. J. Opt. Soc. Am. JOSAA. 25, 1504–1513 (2008).

Oyabu, I., Iizuka, Y., Wolff, E. & Hansson, M. Chemical composition of soluble and insoluble particles around the last termination preserved in the dome C ice core, inland Antarctica. Clim. Past Discuss. 1–22 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2016-42 (2016).

Jouzel, J. & Masson-Delmotte, V. Deep ice cores: the need for going back in time. Q. Sci. Rev. 29, 3683–3689 (2010).

Kjær, H. A. et al. Subannual layer variability in Greenland firn cores. in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts 19, 11581 (2017).

Thomas, E. R. et al. Physical properties of shallow ice cores from Antarctic and sub-Antarctic Islands. Cryosphere 15, 1173–1186 (2021).

Legrand, M. & Wolff, E. W. In Chemistry in the Cryosphere (In 2 Parts) 687–753 (World Scientific, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811230134_0014

Lambert, F., Bigler, M., Steffensen, J. P., Hutterli, M. & Fischer, H. Centennial mineral dust variability in high-resolution ice core data from dome C, Antarctica. Clim. Past. 8, 609–623 (2012).

Mayewski, P. A., Sneed, S. B., Birkel, S. D., Kurbatov, A. V. & Maasch, K. A. Holocene warming marked by abrupt onset of longer summers and reduced storm frequency around Greenland. J. Quat. Sci. 29, 99–104 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Field measurements at Concordia Station were made possible by the joint French-Italian Concordia Program, which established and currently runs the permanent Concordia station at DomeC. We thank the Italian polar program PNRA (Programma Nazionale di Ricerca in Antartide) and the French Polar Institute (Institut Paul Emile Victor, IPEV). Dataset and information from the AWS and Ceilometer are achieved by the Italian Antarctic Meteo-Climatological Observatory (IAMCO) https://www.climantartide.it of the PNRA. This paper is a contribution to the PNRA16\_00231 project “OPTAIR” and PNRA 2015/AC3 LTCPAA (Long-Term Measurements of Chemical and Physical Properties of Atmospheric funded by the Italian National Antarctic Research Program (PNRA). This article is an outcome of Progetto TECLA - Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027, funded by MUR. The authors gratefully acknowledge S. Albani, T. Sanvito, and M. Siano for fruitful discussions. This work is dedicated to the memory of our esteemed colleague Claudio Scarchilli.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP: instrument realization, data analysis and interpretation, and coordination; LC: data analysis and interpretation; BD, SB, RT data analysis and interpretation; MDG: LIDAR realization and data analysis; VC and CS: meteorological data analysis and interpretation; BP, AP and AP: support in the instrument realization; VM: support in data interpretation. MP, LC, SB, BD, VC, and CS wrote the article. All authors contributed to reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Potenza, M.A., Cremonesi, L., Becagli, S. et al. Monitoring optical properties of atmospheric aerosols at dome C, East Antarctic Plateau, provides insights into radiative transfer estimates. Sci Rep 15, 39793 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23538-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23538-2