Abstract

Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) is considered a potentially efficacious technology to modulate response inhibition, but few studies have compared different paradigms and clarified their neurophysiological mechanisms. Thus, to investigate the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) for improving response inhibition in healthy male adults, simultaneously using fNIRS to monitor prefrontal cortex (PFC) hemodynamic changes during tES intervention. A total of 229 healthy participants were randomly divided into tACS, tDCS and sham groups. Results demonstrated that a significant interaction with regard to the Stroop effect (F (2,102) = 4.144, P = 0.019, ηp2 = 0.075). The post-test result of tACS (70.125 ± 43.435) was significantly greater than that of tACS (65.338 ± 45.500). fNIRS revealed tDCS uniquely reduced oxy-Hb concentration in the prefrontal cortex (Channels 7/10: Ps < 0.05). Both tDCS and tACS can significantly reduce the Stroop effect, indicating that both interventions can improve the response inhibition ability. Additionally, tDCS could enhance neural efficiency by reducing the neural resources required to complete the task, particularly highlighting the phenomenon of shifted neural benefits observed during right IFG stimulation. These findings contribute novel insights into understanding the mechanisms underlying enhanced response inhibition through the application of tES techniques, thereby establishing a foundation for future applications in neurological disorder treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When individuals are confronted with a red traffic signal or a rapidly approaching vehicle, they are able to immediately cease their forward motion. In environments such as libraries or cinemas, individuals can regulate the volume of their voices and avoid making excessive noise. These everyday behaviors reflect an important cognitive ability, namely the capacity to inhibit a response. Response inhibition is a pivotal element of executive function1. This ability can control one’s attention, behaviors, thoughts and emotions to overcome strong internal tendencies or external temptations and thus maintain goal-oriented behavior. In the absence of the ability to regulate response inhibition, individuals would be susceptible to the influence of impulses, outdated cognitive processes, established patterns of action, and a multitude of external stimuli2,3. The ability of response inhibition is a fundamental skill for individuals to adapt to the complex and ever-changing environments, maintain social interactions, and succeed in work and study. However, this ability tends to decline with age4. Impairment of this function is also common in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Individuals with these disorders exhibit impaired inhibition, which has a significant impact on their daily lives, social functioning and academic achievement5,6,7.

Previous research has demonstrated that cognitive training, pharmacological interventions, music therapy, and other techniques can improve an individual’s inhibition ability8. However, the efficacy of these approaches varies from person to person, and there are also limitations in practical application. For example, cognitive training is prone to a ceiling effect, whereby the training effect diminishes over time. While pharmacological interventions can effectively alleviate symptoms, they may also have adverse effects. Although interventions similar to music therapy are widely popular, there is not enough empirical research on their effectiveness9. There is a lack of standardization in the formulation and implementation of treatment plans10. To better improve the quality of these patients’ lives, non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques such as transcranial electric stimulation (tES), photobiomodulation (PBM) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (tMS) have become a prominent area of research and clinical intervention in recent years. Among these techniques, tES modulates neuronal activity by applying weak electric currents to the brain, thereby affecting cognitive function. The two main paradigms of tES are transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). tDCS modulates cognitive function by applying weak direct current to alter neuronal membrane potentials, with anodal stimulation enhancing cortical excitability and cathodal stimulation inhibiting it. Its lasting effects stem from synaptic plasticity and optimized neurotransmitter release. tACS synchronizes neural oscillations through alternating current at specific frequencies, enhances phase coupling between brain regions, and improves cognitive control and memory. Its long-term effects depend on neural entrainment and cross-frequency oscillation coordination11,12. Although there is evidence that tES technology can improve executive functions, there is a paucity of comparative studies on the two paradigms (tACS and tDCS) in improving response inhibition. The extant literature has concentrated on functions such as working memory and cognitive flexibility, with relatively few studies investigating the potential of tES technology to enhance response inhibition in healthy adults. Most studies have focused on elderly individuals and psychiatric patients13. In elderly populations, tES enhances response inhibition, with effects modulated by baseline performance and skull anatomy14,15. In psychiatric groups (e.g., ADHD, addiction, schizophrenia), prefrontal tES improves inhibitory control and reduces symptom severity, suggesting clinical utility beyond cognitive enhancement16,17. Additionally, the subthalamic nucleus, pre-supplementary motor area (preSMA) and inferior frontal cortex have been identified as regions engaged during response inhibition tasks18,19,20. And selecting the most effective brain regions for intervention is the key to obtaining significant behavioral outcomes and neural activity. A study by Aron found that an important brain region affecting response inhibition function is the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and patients who exhibited damage to the right IFG showed decreased performance on response inhibition tasks21,22, Jacobson found that activation of the right IFG by unilateral anodic stimulation significantly improves response inhibition23. Therefore, this study selected the right IFG as the target brain area for stimulation and compared the effects of tACS and tDCS on inhibitory control in healthy adults.

The changes in the cerebral cortex caused by tES are complex and not immediately apparent, but can be effectively captured using fNIRS24. As a non-invasive brain imaging technology, fNIRS reflects changes in regional cerebral blood flow by measuring alterations in the concentration of deoxygenated hemoglobin (HHb) and oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) in the cerebral cortex, thereby indirectly assessing the activity of brain function25. To gain a fuller comprehension of the neurophysiological processes underlying tES interventions, this study employed fNIRS to monitor the hemodynamic changes in the participants’ prefrontal cortex in real time. During the experiment, participants were required to complete a series of cognitive tasks while receiving two tES interventions. Monitoring relative hemoglobin concentration changes via fNIRS in the prefrontal cortex throughout intervention phases revealed hemodynamic fluctuations correlating with task difficulty, intervention methodology, and tES parameters.

This study consists of two experiments. Experiment 1 uses behavioral tasks to explore the differences between the two intervention methods. Experiment 2 explores the neural mechanisms behind these differences based on the results of Experiment 1. In summary, the principal objectives of the study were as follows: (1) Verifying whether the right IFG can be modulated using tACS and tDCS to improve executive function. (2) Exploring the neural mechanisms underlying the effects of tACS and tDCS on response inhibition. (3) Comparing the effects of tACS and tDCS. We have made the following assumptions: (1) H1: Both tACS and tDCS will reduce the Stroop effect (indicating improved response inhibition) compared to sham stimulation. (2) H2: tDCS will elicit greater behavioral improvement than tACS. (3) H3: tDCS will reduce oxy-Hb concentration in the PFC during task performance, reflecting enhanced neural efficiency. (4) H4: Functional connectivity within the PFC will decrease post-tDCS, correlating with improved task performance.

Results

Experiment 1: effects of the tACS/tDCS intervention on CW-Stroop task

Table 1 shows the basic information, blinding efficacy and self-reported side effects of subjects. There were no significant differences in age (F(2,102) = 2.061, P = 0.133) and education level (F(2,102) = 2.322, P = 0.103) among these groups. There was no significant difference in the number of correct guesses among these conditions (χ2(4) = 1.02, P = 0.907). In addition, the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed no statistically significant difference in confidence in correct guesses among the tACS, tDCS, and sham groups (P = 0.812), which suggests that the double-blind experimental design used was effective. Regarding the occurrence of side effects of tES, one of the most frequent symptoms was itching, which occurred 3, 4, and 5 times in the three groups. The next most frequently reported symptoms were distraction, headache, and sleepiness, but overall all participants tolerated the discomfort of tES well, reporting side effects that were all mild and transient.

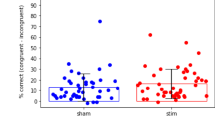

Mixed-design ANOVAs were conducted for groups (tACS, tDCS, and sham) and time periods (prestimulation and poststimulation) in the CW-Stroop task. The results of the analysis demonstrated a statistically significant interaction with regard to the Stroop effect (F(2,102) = 4.144, P = 0.019, ηp2 = 0.075) (Fig. 1), suggesting that the effect of the different intervention modalities on task performance changed with the stage of stimulation. Subsequently, the results of the simple effects analysis showed that the Stroop effect was significantly reduced (Ps = 0.001) after the tACS/tDCS intervention, which means that the subjects’ reaction times were all reduced after the intervention. The difference between the pre and post-test scores of tDCS and tACS was significant. Post-test result of tACS (70.125 ± 43.435) was greater than that of tDCS (65.338 ± 45.500), but the difference was not statistically significant. No significant difference was observed in the performance of the sham group in the pre- and post-test. In addition, according to Table 2, we can also find that the response time at post-test decreased in the tDCS group, tACS group and sham group, where the decrease in the sham group may be due to the placebo effect, which further validates the double-blind experimental design of the sham group. In terms of accuracy, the interaction among the three CW-Stroop task conditions and time was found to be statistically significant (F(2,102) = 3.820, P = 0.025). A simple effects analysis revealed that the differences between the pre-test and post-test and the CW-Stroop task conditions were significant in the congruent condition, while none of the remaining comparisons reached statistical significance. Furthermore, the mean values for subject responses were analyzed, a method commonly employed in statistical analyses to assess and compare the speed of response across conditions. It reflects the average time it takes for an individual or group to respond to a stimulus under certain stimulus conditions26. The results of the one-way ANOVA indicated that the mean values of response time exhibited no statistically significant difference among the three groups in either the pre-test or the post-test (pre: F(2,102) = 1.595, P = 0.208; post: F(2,102) = 1.481 P = 0.232). This finding suggests that the speed of response was not significantly different among the three groups of subjects. The behavioral results did not provide evidence to differentiate between the effects of the two interventions, and therefore the data on cortical activity need to be analyzed further in Experiment 2.

Stroop effect of the CW-Stroop task in prestimulation and poststimulation. The boxes extend from the 25th to the 75th percentile, with a horizontal line representing the median and whiskers showing the minimum to maximum values. Colored dots indicate individual data. Bonferroni-corrected contrast: *P < 0.05.

Experiment 2: effect of tACS/tDCS on PFC hemodynamic activity

Table 3 illustrates that at baseline, no significant differences existed among these groups of subjects in regard to age and education level. There was also no significant difference in the number of correct guesses among these groups (χ2(4) = 3.85, P = 0.427). In addition, there was no significant difference in confidence in correct guesses among these groups according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (P = 0.808). All participants tolerated the discomfort of receiving tES well, and reported side effects were mild and transient.

Based on the group’s previous findings27, matrices of the strength of functional connectivity among the three groups (tACS, tDCS, sham) of each channel in the domain of executive function were obtained for the three stimulus phases, using the Pearson correlation coefficient as an index. The channel pairs exhibiting significant interaction effects were channels 3–10 and channels 7–13. The one-way ANOVA of the variations in activation of channel 3, channel 10, channel 7 and channel 13 showed that significant activation changes only occurred in the stimulation phase, and in these channels there were no significant differences during the prestimulation and poststimulation stages (Ps > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 2A, a plot based on the F values of each channel by one-way ANOVA indicated that significant changes in activation (channel7: F(2,121) = 3.627, P = 0.030; channel10: F(2,121) = 4.116, P = 0.019) were mainly concentrated in the frontal pole region (channels 7 and 10). Further simple effect analysis showed that the activation in channels 7 and 10 of the tDCS group was significantly lower than that of the sham group in the stimulation phase, but no such significant change was observed in the tACS group (Fig. 2B).

(A) The F value of the oxy-Hb concentrations of all channels after one-way ANOVA, and significantly changed channels are indicated in white. (B) Variations in the activation of channels 7 and 10 among the three groups. The boxes extend from the 25th to the 75th percentile, with a horizontal line representing the median and whiskers showing the minimum to maximum values. Colored dots indicate individual data. Bonferroni-corrected contrast: *P < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study explored effects of tACS and tDCS on the activation patterns and behavioral performance of right IFG in a response inhibition task in healthy adults by combining tES and fNIRS techniques, revealing the neural mechanisms underlying the response inhibition28.

tES is an effective method for improving cognitive performance in healthy individuals or patients with cognitive impairment, but comparative studies on the improvement of response inhibition with different tES paradigms are lacking. We found significant improvements in behavioral performance related to response inhibition after the tACS and tDCS stimulation. In addition, the majority of existing tDCS studies use conventional tDCS, which involves the use of an anode and cathode comprising two rectangular optode patches with an area of approximately 25–35 cm². This approach has several limitations. The spatial resolution of the stimulus is insufficient, current conduction is dispersed, and it is unable to accurately stimulate specific brain areas29. This not only reduces the effectiveness on the cerebral cortex but also makes it challenging for researchers to interpret the neurological mechanisms behind the observed behavioral outcomes. However, HD-tDCS has been demonstrated to address these issues more effectively, as evidenced by its use in this study28. The use of small-diameter circular electrodes allows for the implementation of a central electrode in the target area, surrounded by four return electrodes in a circular configuration. This enables the conduction of higher spatial resolution currents, which can be employed to modulate cortical excitability and behavioral performance30. Concurrently, this method yields more pronounced behavioral or neurophysiological outcomes than those observed with conventional tDCS31,32,33,34.

Our study demonstrated that both tDCS and tACS stimulation of the right IFG in healthy male adults can significantly reduce the Stroop effect. These findings are consistent with those of Liron Jacobson, who reported that activation of the right IFG by anodic stimulation improved response inhibition19,23. In a study by Fujiyama et al., both right IFG and pre-SMA were anodically stimulated and sham stimulated, and it was found that compared to sham stimulation, anodic stimulation of pre-SMA enhanced response inhibition in an elderly population, whereas stimulation of right IFG had no effect35. This suggests that the intervention effect of tDCS is different on healthy groups of different ages, and the migratory nature of the effect of tDCS needs to be further verified. Such differences may stem from physiological and psychological differences between individuals. Firstly, age-related differences may result in variations in the functionality and connectivity of specific brain regions. In comparison to younger populations, older populations may exhibit a reduction in brain region connectivity, which may contribute to an enhanced improvement in response inhibition resulting from pre-SMA anodic stimulation. Secondly, the cognitive load and attention allocation among individuals may impact the efficacy of brain area stimulation. For certain tasks that necessitate a high level of attention and cognitive control, right IFG stimulation may prove more beneficial, whereas for tasks that require complex cognitive processes, pre-SMA stimulation may offer a more advantageous outcome.

In this study, we mainly focused on the stimulation effects of the right IFG, and we also closely observed the functional connectivity changes of the PFC, which plays a key role in the development of most cognitive functions in humans. Previous studies have shown that the PFC is not only engaged in high-level cognitive tasks, such as self-control, decision-making, social behavior and planning, but is also closely related to emotion regulation and attention focusing36,37. Therefore, understanding the functional changes of the PFC after stimulation is important for our understanding of the neural mechanisms of cognitive function. Our study found that after tDCS, the strength of functional connectivity between the right IFG and the PFC, as well as within the PFC, decreased significantly27. This result differs from previous findings in that this reduction in the strength of functional connectivity can be interpreted as an increase in neural efficiency. This means that communication between neurons can be maintained with less connection strength for the same or even higher levels of cognitive performance38,39. Instead of more neurons in the brain performing complex tasks, efficient information transfer is achieved by optimising the structure and function of neural networks. This explains why a reduction in the strength of functional connectivity after tDCS stimulation does not mean that cognitive function decreases; rather, it may mean that the brain is more efficient in neuronal connectivity, leading to higher cognitive performance. During the stimulation phase, we found that activation of channels 7 and 10 was lower in the tDCS intervention than in the other two groups. Similar to our previous findings, lower levels of activation in the functional regions of the brain were associated with higher levels of performance in attentional inhibition and lower levels of cognitive cost. The stimulated target region was the right IFG, but significant activation changes were only observed in the PFC region, suggesting that tDCS affects not only the stimulated brain region but also other brain regions. The experimental results showed that participants treated with tDCS had the highest mean correct rate on the CW-Stroop task, which may be related to the long-term enhancement effect of tDCS on the right IFG, resulting in better performance on the task11,40. Meanwhile, the fNIRS data showed that the change in blood oxygenation activity was lower in the tDCS group compared with the sham group during the stimulation phase, which may indicate that tDCS improves neural efficiency and reduces the neural resources required to complete the task. However, there was no significant change observed in the tACS group. First, from the perspective of neurovascular decoupling, tACS primarily relies on neural oscillation synchronization (20 Hz beta waves in this study), which may not directly correspond to the hemodynamic changes observed by fNIRS41. Second, the fNIRS coverage area may not fully align with the stimulated inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (e.g., some channels may monitor the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), and high-precision tACS may require a denser fNIRS array to capture subtle changes. Finally, the selected 20 Hz beta wave stimulation may be less effective due to individual differences in baseline oscillation frequencies42,43. Therefore, tDCS may be more effective than tACS in enhancing response inhibition (although this difference is not significant), which is related to the differences in the neurophysiological mechanisms of the two stimulation modalities. tDCS controls cortical excitability by modulating neuronal membrane potentials, whereas tACS facilitates neural synchronization by stimulating neuronal oscillations. While both methods have the potential to enhance executive function, the findings suggest that tDCS may be more effective in modulating specific cognitive functions.

However, the current study has the following limitations. First, although many participants were recruited and there were no differences in the demographic information of the participants, the sample size of this study was primarily for healthy adult males and lacked a female sample. There are gender differences in the short-term neuroplasticity induced by tDCS in the visual cortex, which may be related to hormone levels or cortical structural differences. In the future, gender-balanced designs will be needed to validate the universality of neurovascular coupling mechanisms44. Secondly, the stimulation parameters and durations for the current study were determined based on existing literature, but optimal stimulation parameters may vary depending on individual differences; future research should consider individualized stimulation parameters, as well as a broader group of neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, this study did not explore the long-term effects of tES intervention and potential neuroplasticity changes. Future studies could focus on long-term follow-up after tES intervention, as well as incorporating other neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI, to more fully understand the effects of tES on brain function. Finally, due to the limited number of fNIRS channels in the study, which were set up around the right IFG but did not fully cover this brain region, it was also not possible to measure all of the brain regions associated with executive function. Future studies may require more comprehensive and purer neuroimaging evidence and monitoring of a larger range of brain regions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both tDCS and tACS applied to the right IFG significantly enhance response inhibition in healthy adults, with tDCS being more effective. Simultaneous fNIRS assessments revealed that tDCS reduces cortical activation during task performance, indicating enhanced neural efficiency through lower metabolic demands. These findings establish tDCS as the more effective modality for modulating inhibitory control, providing a targeted, non-pharmacological strategy for treating disorders of impulsivity (e.g., ADHD, OCD). This work advances the clinical translation of neuromodulation by linking behavioral gains to neural efficiency, paving the way for personalized tES protocols in cognitive rehabilitation. Furthermore, tDCS, as a safe and non-invasive method, offers an alternative for patients who are reluctant or unable to use pharmacological treatments.

Methods

Participants

A total of 229 healthy adult male participants (mean ± SD age of 22.17 ± 2.52 years) were included in this study. The number of participants in Experiment 1 was 105, while Experiment 2 involved 124 participants. The participants were randomly allocated to one of three experimental groups which were the tACS group, the tDCS group and the sham group. No significant differences were observed in age among the three groups (F(2,226) = 1.493, P = 0.227). And all subjects were right-handed (Edinburgh handedness scores of 90 ± 12), native Chinese speakers, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, were not taking any medication and reported no history of neurological or psychiatric diseases during the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University (KY20202063-F-2). All participants signed a consent form and had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Our determination of specific parameters were directly informed by the methodology of Lu et al. (2023)27, as both studies share a highly similar focus on investigating the modulation of cognitive functions using tES. Following their approach, we used G*Power 3.1.9.6 to conduct an a priori power analysis. the required sample size was estimated by G*Power 3.1.9.6, which showed that a minimum of 54 participants were required for each experiment45. The specific parameters were: medium effect size (0.25), 1 - β = 0.90, and α = 0.0546,47.

Experimental procedure and task

This study used the CW-Stroop task, which is a task widely used in psychology to assess an individual’s inhibition ability. This task requires individuals to focus on the color rather than the meaning of words when identifying words with conflicting semantics and color. The design of this task cleverly examines the ability of individuals to regulate and control behavior when faced with conflicting information. The task flow is shown in Fig. 1. A symbol of a random color (‘XX’) or Chinese character (‘红’,‘黄’,‘蓝’,‘绿’) appears in the middle of the screen. The stimulus’s presentation time is 500ms, and the interval between each two stimuli is 1500ms. The background color is black, the font format is ‘bold’, and the font size is 40. During the course of the task, participants were required to press the appropriate keyboard button in response to the color displayed, in a prompt and accurate manner. In the event that the color of the symbol or Chinese character is red, yellow, blue or green, the corresponding ‘D’, ‘F’, ‘J’ or ‘K’ keys should be pressed (Fig. 3A). The three conditions involved in the task (neutral trials, congruent trials and incongruent trials) appeared in a 1:1:1 ratio. There are 20 practice trials for each condition, followed by 108 formal trials. This study used E-Prime software 3.0.10 to design and present CW-Stroop task.

Figure.3B shows the procedures and details of Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. Participants were asked to complete a motivational, demographic questionnaire prior to the experiment, followed by the collection of subjects’ brain activity in the resting state. In order to ensure the validity of the experiment, the sham group and active group adopted a double-blind experimental design, where the experimenters were not involved in the setting of tES parameters and could only see the code names of the three groups, and the detailed parameters were not displayed on the operation interface. The objective of Experiment 1 was to investigate the potential of tES to facilitate response inhibition behavior. The assessment of cognitive change at different stages of the stimulus was conducted through the analysis of response time, correctness and the Stroop effect of the CW-Stroop task. The Stroop effect was calculated by subtracting the response time in the incongruent condition from the response time in the congruent condition. The total task time in Experiment 1 is 45 min, with data collected 15 min before and after the stimulus, and the stimulus lasting 10 min respectively. Experiment 2 used fNIRS to continuously monitor the changes in cerebral hemodynamics at three stages to explore the different effects of tACS and tDCS on brain function; The task time in Experiment 2 is 16 min in total, and data are collected for 3 min before and after the stimulation, which also lasted 10 min.

(A) Procedure of CW-Stroop task. The CW-Stroop task was used to measure ability of response inhibition. Chinese characters and symbols of different colors will appear at random on the screen. The subjects are required to press the corresponding keys in accordance with the color that is displayed. The keys that correspond to the colors red, yellow, blue and green are D, F, J and K, respectively. (B) The designs of Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. The study had three groups: tACS, tDCS and sham. Each experiment was divided into three stages (prestimulation, stimulation, and poststimulation).The intervention time for Experiments 1 and 2 was 10 min.

Interventions

tES was delivered by a Soterix Medical M×N-33 High-Definition Transcranial Electrical Stimulator (Soterix Medical, Inc., New York, United States) in the study (Fig. 4A). The diameter of each electrode is 12 mm. This study used HD-tDCS. Compared to traditional tDCS, HD-tDCS uses a multi-electrode surround arrangement mode, which produces a more concentrated and stronger current, resulting in more accurate and efficient stimulation. The center of the right IFG electrode was placed on FC6, and four return electrodes were placed at F6, FT8, C6, and FC4 according to the International 10–20 system48. Additionally, we used the HD-explore software (Soterix Medical) to simulate the theoretical electric fields and current intensities to ensure the efficiency of the electrode montage. In the tACS condition, stimulation lasted 10 min at an intensity of 1.5 mA in the β band (20 Hz). In the tDCS condition, the center electrode was the anodal electrode and four return electrodes were cathodal electrodes while the current intensity and duration were the same as those in the tACS condition. This intensity and duration have been shown to induce beneficial effects on cognitive function in both healthy and clinical populations49,50. The electrode placement in the sham-tDCS was identical to that of real-tDCS but the stimulation lasted only 60 s. For both conditions, the current was ramped up and down in each 30 s. Participants performed the CW-Stroop task during the stimulation. The stimulation employs a self-crafted electrode cap, which has successfully been patented. At the end of the experiment, each participant was asked to complete a blinded effects questionnaire indicating whether or not they thought they had been subjected to a real or sham stimulation and how confident they were in this judgment. In addition, participants were asked to complete a side-effects questionnaire to assess whether they experienced any abnormal sensations that might be associated with the stimulus.

Data collection and analysis

The LABNIRS fNIRS system, applied in this study, has a total of 14 channels that emit light at 780, 805 and 830 nm (sampling frequency is 27.78 Hz). According to the International 10–20 system, Fpz and FC6 were used as the frontal pole region and right IFG region, respectively. For each participant, a 2 × 2 optode patch (4 channels, 2 emitters and 2 detectors) was placed on the right side of the head and FC6 was set as the reference point. Then, a 2 × 2 optodes (4 channels, 2 emitters and 2 detectors) was placed on the right side of the head with FC6 as the reference point to record the change in the right IFG. Using Fpz as a reference point, a 4 × 2 electrode array (8 channels, 4 emitters and 4 detectors) was placed symmetrically on the forehead to record changes in the frontal pole region (Fig. 4B)51,52. In this study, the distance between the emitter of the light source and the adjacent detector is set to 30 mm. It is noteworthy that the design of the optode patch at the right IFG position was aligned with that of the tES optode patch, and the anode electrode (FC6) was encased within four optode patches. To ensure the quality of the acquired brain signals and avoid the problem of weak electrode contact caused by the movement of the electrode pads in Experiment 2, a brain stimulation cap with integrated real-time signal acquisition was designed and adopted in this study (Fig. 4C). We fixed the optode patches in the exact position with plastic tape that did not cause deformation. A ‘+’ was marked in the center of the screen, and each participant was asked to keep their eyes open as much as possible in a relaxed state and to remain as still as possible.

(A) The details of electrical stimulation of the right IFG are shown, displayed from three slices: Coronal slice, Sagittal slice and Axial slice. The redder the colour, the higher the activation. And the theoretical current intensity on the right IFG is predicted with Soterix HD-Explore software. The software name is HD-Explore, brand is Soterix Medical, and version is 5.0. (B) A cap for multibrain stimulation combined with real-time signal acquisition was designed and applied in this study. We used nondeforming plastic tape to hold the optode patch in place to sustain the relative distance between the adjacent optodes or electrodes (ZL 2022 2 3443116.1). (C) The arrangement of optodes and electrodes. Four channels and five current electrodes around FC6 were placed to modulate or measure activity in the right IFG, and the other 10 channels were placed adjacent to the Fpz to measure activity in the frontal pole region. The red circles indicate the positions of anodal electrodes, and the blue circles indicate the positions of cathodal electrodes; the specific intensities of the five electrodes were FC6 (1.5 mA), F6 (− 0.37 mA), FT8 (− 0.38 mA), C6 (− 0.37 mA), and FC4 (− 0.38 mA).

To ensure the quality of the subjects’ responses, data with response times ≤ 150ms or ≥ 1500ms were excluded from this study. In this study, the LABNIRS acquisition and analysis software was employed to transform the ‘om’ file into ‘txt’ format, and the Homer_2 toolbox was utilised to convert the ‘txt’ data into the Homer_2-supported ‘nirs’ format. The Homer_2 toolbox was then used to convert the ‘txt’ data into the ‘nirs’ format supported by Homer_2. In the initial stage of data preprocessing, the raw light intensity was transformed into optical density (OD), then the enPCA function was used to reduce the physiological noise, and the motion artefact correction method (MARA) was used to correct the time windows containing artefacts. In addition, the hmrMotionArtifactByChannel function is applied to identify motion artefacts and corrected using the MotionCorrectSpline function. The OD was converted into changes in HbO2 and HHb concentrations, in accordance with the Beer-Lambert law. The data on changes in HbO2 concentrations were employed as the primary indicators, while the data on changes in HHb concentrations were used as a secondary indicator. To guarantee uniformity in data processing, functional connectivity analyses were conducted using data of identical duration, specifically 3 minutes prior to, during, and following the presentation of the stimulus. Finally, Pearson correlation analysis was performed on the data of HbO2 concentration changes of 14 channels in each group during the three stimulation phases, and the Fisher z-transformed Pearson correlation coefficients between the channels were used as an evaluation index of the strength of functional connectivity53.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS statistical ver.25 software was applied for the statistical analyses, with a significance level of 5%. A mixed repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the CW-Stroop performances before and after each intervention. Further exploration of significant interaction effects was conducted via simple effects analysis, with multiple comparisons adjusted through the application of the Bonferroni correction. In addition, effect sizes were reported as biased eta-squared (ηp2) values.

Data availability

All data can be obtained by sending an email to the author. If you need it, you can contact Hongliang Lu. The e-mail address is luhongliang@fmmu.edu.cn.

References

Chan, A. S., Han, Y. M. Y., Leung, W. W., Leung, C. & Wong, V. C. N. Abnormalities in the anterior cingulate cortex associated with attentional and inhibitory control deficits: A neurophysiological study on children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disorders. 5 (1), 254–266 (2011).

Brocki, K. C. & Bohlin, G. Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study. Dev. Neuropsychol. 26 (2), 571–593 (2004).

Diamond, A. Executive functions. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 64, 135–168 (2013).

Bloemendaal, M. et al. Contrasting neural effects of aging on proactive and reactive response Inhibition. Neurobiol. Aging. 46, 96–106 (2016).

Chen, S. & Wang, E. Characteristics of response Inhibition in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Adv. Psychol. 5 (10), 536–541 (2020).

Chen, Z. & Qing, F. A review of deficits in response Inhibition of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Chin. Mental Health J. 38 (4), 306–311 (2024).

Sun, Y., Ke, X. & Pan, H. Response Inhibition in children with high functioning autism: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Chin. Mental Health J. 24 (6), 450–454 (2010).

Koyun, A. H. et al. Effects of catecholaminergic and transcranial direct current stimulation on response Inhibition. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol., 27(6). 1–11 (2024).

Xiao, R. et al. The influence of music tempo on inhibitory control: an ERP study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 14, Article123 (2020).

Echiverri-Cohen, A. et al. Randomized-controlled trial of response Inhibition training for individuals with PTSD and impaired response Inhibition. Behav. Res. Ther. 143, 103885 (2021).

Woods, A. J. et al. A technical guide to tDCS, and related non-invasive brain stimulation tools. Clin. Neurophysiol. 127 (2), 1031–1048 (2016).

Grover, S. et al. A meta-analysis suggests that tACS improves cognition in healthy, aging, and psychiatric populations. Sci. Transl. Med. 15 (712), eabo2044 (2024).

Hill, A. T., Rogasch, N. C., Fitzgerald, P. B. & Hoy, K. E. Effects of single versus dual-site High-Definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) on cortical reactivity and working memory performance in healthy subjects. Brain Stimul. 11 (5), 1033–1043 (2018).

Hsu, T. Y. et al. Modulating inhibitory control with direct current stimulation of the superior medial frontal cortex. NeuroImage 56 (4), 2249–2257 (2011).

Stramaccia, D. F. et al. Assessing the effects of tDCS over a delayed response Inhibition task by targeting the right inferior frontal gyrus and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 233 (8), 2283–2290 (2015).

Brunelin, J. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. Brain Sci. 8 (2), 37 (2018).

Guo, Z. H., Lu, H. L., Huang, P. & Zhu, X. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on response Inhibition in healthy people. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 30 (9), 2034–2052 (2022).

Rubia, K., Smith, A. B., Brammer, M. J. & Taylor, E. Right inferior prefrontal cortex mediates response Inhibition while mesial prefrontal cortex is responsible for error detection. NeuroImage 20 (1), 351–358 (2003).

Aron, A. R. & Poldrack, R. A. Cortical and subcortical contributions to stop signal response inhibition: role of the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 26 (9), 2424–2433 (2006).

Sandrini, M. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation facilitates response Inhibition through dynamic modulation of the fronto-basal ganglia network. Brain Stimul. 13 (1), 96–104 (2020).

Chambers, C. D. et al. Executive brake failure following deactivation of human frontal lobe. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18 (3), 444–455 (2006).

Aron, A. R., Fletcher, P. C., Bullmore, E. T., Sahakian, B. J. & Robbins, T. W. Stop-signal Inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 6 (2), 115–116 (2003).

Jacobson, L., Javitt, D. C. & Lavidor, M. Activation of inhibition: diminishing impulsive behavior by direct current stimulation over the inferior frontal gyrus. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 (11), 3380–3387 (2011).

Dutta, A. Simultaneous functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and electroencephalogram (EEG) to elucidate neurovascular modulation by transcranial electrical stimulation (tES). Brain Stimul. 14 (5), 1093–1094 (2021).

Scholkmann, F. et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. NeuroImage 85, 6–27 (2014).

Gao, X. & Li, Z. The trade-off between speed and accuracy: evaluation and modeling for participants in the response States. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 17 (5), 589–595 (2019).

Lu, H. et al. A new perspective for evaluating the efficacy of tACS and tDCS in improving executive functions: A combined tES and fNIRS study. Hum. Brain. Mapp., 45(1), 1–14 (2024).

Kim, J., Kim, H., Jeong, H., Roh, D. & Kim, D. H. tACS as a promising therapeutic option for improving cognitive function in mild cognitive impairment: A direct comparison between tACS and tDCS. J. Psychiatr. Res. 141, 248–256 (2021).

Singh, A., Erwin-Grabner, T., Goya-Maldonado, R. & Antal, A. Transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation in the treatment of depression: basic mechanisms and challenges of two commonly used brain stimulation methods in interventional psychiatry. Neuropsychobiology 79 (6), 397–407 (2020).

Minhas, P. et al. Electrodes for high-definition transcutaneous DC stimulation for applications in drug delivery and electrotherapy, including tDCS. J. Neurosci. Methods. 190 (2), 188–197 (2010).

Stagg, C. J. & Nitsche, M. A. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 17 (1), 37–53 (2011).

Bortoletto, M. et al. Reduced current spread by concentric electrodes in transcranial electrical stimulation (tES). Brain Stimul. 9 (4), 525–528 (2016).

Kuo, H. I. et al. Comparing cortical plasticity induced by conventional and high-definition 4 × 1 ring tDCS: a neurophysiological study. Brain Stimul. 6 (4), 644–648 (2013).

Martin, A. et al. The right temporoparietal junction is causally associated with embodied perspective taking. [Unpublished manuscript]. (2019).

Fujiyama, H. et al. Influence of tDCS over right inferior frontal gyrus and pre-supplementary motor area on perceptual decision-making and response inhibition: A healthy ageing perspective. Neurobiol. Aging. 109, 11–21 (2022).

Funahashi, S. Neuronal mechanisms of executive control by the prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Res. 39 (2), 147–165 (2001).

Koechlin, E., Ody, C. & Kouneiher, F. The architecture of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science 302 (5648), 1181–1185 (2003).

Lu, H. et al. Transcranial electrical stimulation offers the possibility of improving teamwork among military pilots: A review. Front. NeuroSci. 16, 931265 (2022).

Fritsch, B. et al. Direct current stimulation promotes BDNF-dependent synaptic plasticity: potential implications for motor learning. Neuron 66 (2), 198–204 (2010).

Fregni, F. et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Exp. Brain Res. 166 (1), 23–30 (2005).

Wansbrough, K. et al. Beta tACS of varying intensities differentially affect resting-state and movement-related M1-M1 connectivity. Front. Neurosci. 19 (18), 1425527 (2024).

Agboada, D., Zhao, Z. & Wischnewski, M. Neuroplastic effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS): from mechanisms to clinical trials. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 19, 1548478 (2025).

Song, N. et al. Harnessing theta waves: tACS as a breakthrough in alleviating post-stroke chronic pain. Front. NeuroSci. 19, 1553862 (2025).

Chaieb, L., Antal, A. & Paulu, W. Gender-specific modulation of short-term neuroplasticity in the visual cortex induced by transcranial direct current stimulation. Vis. Neurosci. 25 (1), 77–81 (2008).

Cohen, J. Eta-squared and partial eta-squared in fixed factor ANOVA designs. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 33 (1), 107–112 (1973).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 (1), 155–159 (1992).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39 (2), 175–191 (2007).

Holland, R. et al. Speech facilitation by left inferior frontal cortex stimulation. Curr. Biol. 21 (16), 1403–1407 (2011).

McIntire, L. K. et al. A comparison of the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation and caffeine on vigilance and cognitive performance during extended wakefulness. Brain Stimul. 7 (4), 499–507 (2014).

Martin, D. M. et al. Can transcranial direct current stimulation enhance outcomes from cognitive training? A randomized controlled trial in healthy participants. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (9), 1927–1936 (2013).

Lu, K., Yu, T. & Hao, N. Creating while taking turns, the choice to unlocking group creative potential. NeuroImage 219, 117025 (2020).

Lu, H. et al. Increased interbrain synchronization and neural efficiency of the frontal cortex to enhance human coordinative behavior: A combined hyper-tES and fNIRS study. NeuroImage 282, 120385 (2023).

Hocke, L. et al. Automated processing of fNIRS Data—A visual guide to the pitfalls and consequences. Algorithms 11 (5), 67 (2018).

Funding

This research received four fundings: Rapid Response Project of Air Force Medical University (2023KXKT0570). Joint Founding Project of Innovation Research Institute, Xijing Hospital (LHJJ24XL09). Major Project of AFMU (2022ZZXM017). Joint Founding Project of Innovation Research Institute, Xijing Hospital (LHJJ24XL08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Hongliang Lu, Cheng Cheng and Yajuan Zhang; Data curation, Hongliang Lu, Cheng Cheng, Ke Xu, Tengfei Pan and Yinchuan Jin; Formal analysis, Ke Xu, Li Guo; Funding acquisition, Yajuan Zhang and Yinchuan Jin; Investigation, Hongliang Lu, Cheng Cheng, Ke Xu and Tengfei Pan; Methodology, Hongliang Lu and Cheng Cheng, Li Guo; Project administration, Yajuan Zhang and Yinchuan Jin; Resources, Yajuan Zhang and Yinchuan Jin; Supervision, Yajuan Zhang and Yinchuan Jin; Visualization, Hongliang Lu; Writing – original draft, Hongliang Lu, Cheng Cheng, Ke Xu and Tengfei Pan, Li Guo; Writing – review & editing, Hongliang Lu, Cheng Cheng, Yajuan Zhang and Yinchuan Jin.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University. (KY20202063-F-2).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, H., Cheng, C., Xu, K. et al. Enhancing response inhibition through a novel tES-fNIRS framework. Sci Rep 15, 40011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23578-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23578-8