Abstract

This study compared three multiplex immunoassay platforms, Meso Scale Discovery (MSD), NULISA, and Olink, for detecting protein markers in stratum corneum tape strips, a non-invasive sampling method challenged by low protein yield. We evaluated 30 shared proteins across all three platforms, plus 9 additional proteins shared only between MSD and NULISA, and 1 between MSD and OLINK, using samples from non-lesional skin and skin affected by patch test-induced irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, and clinical hand dermatitis. Proteins were considered detectable when more than 50% of samples exceeded the platform’s protein-specific detection limit. MSD demonstrated the highest sensitivity, detecting 70% of shared proteins, followed by NULISA (30%) and Olink (16.7%). Four proteins, CXCL8, VEGFA, IL18, and CCL2, were detected by all three platforms with interclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.5 to 0.86. The three platforms exhibited similar differential expression patterns between control and dermatitis-affected skin, supporting overall concordance. MSD uniquely provided absolute protein concentrations, enabling normalization for variable SC content, while NULISA and Olink required smaller sample volumes and fewer assay runs. Generalizability to other diseases and biomarkers requires further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stratum corneum tape stripping (SCTS) is a widely used, non-invasive method for studying biomarker profiles in various skin diseases, including atopic dermatitis (AD), contact dermatitis (CD), skin cancer, and psoriasis1,2. However, studies using SCTS often report only a limited number of biomarkers, which may be due to their low concentrations in the stratum corneum, limited assay sensitivity or the narrow range of biomarkers targeted by existing assays. An increasing number of studies have employed SCTS in combination with multiplex immunoassays to expand the range of detectable biomarkers3,4,5,6. Multiplex immunoassays have emerged as powerful tools capable of simultaneously measuring multiple proteins from small sample volumes. Several platforms are currently available, with recently introduced platforms like NULISAATM reporting attomolar sensitivity and the ability to analyze hundreds of proteins from as little as 10 µL of sample7. Immunoassays offer distinct advantages over mass spectrometry-based proteomics, as they generally involve more straightforward sample preparation, analysis, and data interpretation, although mass spectrometry remains valuable for its high sensitivity and ability to analyze a broader range of proteins. While multiple studies have compared multiplex techniques from blood-based samples and other biosamples7,8,9,10, no comparative studies have yet been conducted for SCTS samples. Identifying the most sensitive platform for specific biomarker, is essential to advancing SCTS-based biomarker research. Furthermore, understanding how well results correlate across different platforms will enhance the comparability of studies using varied analytical techniques.

In this study we compare three multiplex immunoassays: 250-plex Nucleic Acid Linked Immuno-Sandwich Assay (NULISA™), Olink Explore 96-plex Inflammation Panel (Olink), and Mesoscale Discovery U-plex and V-plex inflammatory and angiogenesis panels (MSD). MSD and Olink have previously been used for the analysis of SCTS in various inflammatory skin diseases1,3,4,5,11,12, while NULISA, a more recent platform, has so far only been used for blood analyses in Alzheimer and COVID diseases7,8. NULISA offers a preconfigured panel of 246 proteins, while MSD and Olink provide greater flexibility in panel selection. Despite the broader selection available on MSD and Olink, we chose specific panels from these platforms to maximize the number of shared proteins across all three platforms. The selected panels had 30 shared protein markers across all three platforms, 12 additional overlapping proteins between NULISA and MSD, and one protein shared between MSD and Olink. Samples used for evaluation of investigated platforms were collected from patients with contact dermatitis (CD), a common and burdensome inflammatory skin disease in the workplace. CD is typically classified as irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), which have similar pathophysiology but identical clinical presentation. There is an unmet need for non-invasive biomarkers to differentiate ACD from ICD1,11,13. This study, part of a project on biomarkers for occupational hand dermatitis, aimed to identify a non-invasive, sensitive method that can capture the pathophysiology of both types of CD.

This study has three objectives:

-

1.

Compare biomarker detectability across three multiplex immunoassay platforms using SCTS samples.

-

2.

Evaluate each platform’s ability to differentiate between non-affected and dermatitis-affected skin.

-

3.

Assess the agreement of protein levels across platforms.

Methods

Biomarkers were analyzed in stratum corneum tape strips (SCTS) obtained from patients with hand dermatitis (HD) who underwent patch testing on the back skin as part of routine diagnostics. Two types of samples were collected: first, SCTS were obtained from the sites of positive patch test reactions to one of allergens including nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), methylisothiazolinone (MI), and sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) as a model irritant, along with a control sample from a petrolatum patch site. Second, SCTS were collected from the hands of the patients presenting with HD.

Samples obtained from positive reactions to one of the allergens were classified as allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), while samples obtained from positive reactions to SLS were classified as irritant contact dermatitis (ICD). The HD samples were collected from lesions of unknown etiology, possibly representing ICD, ACD, atopic dermatitis, or mixed conditions. After extraction with a buffer, protein markers were analyzed using three platforms. They shared 30 common proteins, and additionally, MSD and NULISA shared 12 proteins not included in Olink, and one protein shared between MSD and Olink. Comparisons between the platforms were made based on the overall detectability of protein biomarkers included in the assays, the detectability of shared proteins across platforms, and each platform’s ability to distinguish control skin from ICD, ACD, or HD samples. Correlations in protein biomarker levels across the platforms were also assessed. Details of the study procedure are outlined in Fig. 1.

Study participants

Patients (n = 28) were recruited at the Occupational Dermato-allergology Clinics of the Amsterdam UMC. The experimental protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Amsterdam UMC (Reference number W23_108#23.132). Informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Patch testing

The patch testing was done with European standard allergen series and a model irritant sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) (2% w/w) as a part of the routine diagnostic procedure for hand dermatitis (HD). Participants with a positive patch reaction (1+ or 2+) to allergens nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), methylisothiazolinone (MI), and sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) as a model irritant were invited to participate. Patch testing was conducted in line with the guidelines established by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis14. Patch testing was performed with allergen preparations from Smart Practice Europe (Greven, Germany) which were filled in Allerg EAZE clear chambers (Smart Practice Europe) and placed on the upper back of the patients. As control, a chamber with petrolatum (pet.) was applied. The chambers were removed on the third day after application and grading of the reaction (+, ++, +++) was performed on the fourth day (i.e. 96 h after patch application).

Sample collection

The stratum corneum (SC) samples were collected from the patch tested skin including petrolatum control and from the lesional skin of the patient’s hand (HD). To collect SC, circular adhesive tape strips (1.5 cm2, DSquame; CuDerm, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.) were applied to the skin and pressed down for 5 s with consistent pressure as described previously11. The tapes were pulled off using tweezers and transferred into sample vials and stored until analysis at −80 °C. From each skin site 10 consecutive strips were collected. For the analyses, 4th, 6th and 7th tape strips were used. Previous studies have shown stable cytokine concentrations in these SCTS3.

Sample preparation

To the 4th tape, 0.8 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 0.005% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) was added. PBS buffer contained phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4), Sodium Chloride (NaCl) and Sodium Phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4-7H2O) with pH of 7.4. The sample was sonicated in an ice bath for 15 min using an ultrasound bath (Branson 5800, Ede, The Netherlands) as described previously11. The extract was subsequently used for extraction of the 6th tape, with the resulting extract applied to the 7th tape. The extract was then aliquoted into 200 µL portions and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Protein marker analysis

The extracts were analyzed using three multiplex immunoassay platforms: Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) U-PLEX and V-PLEX Custom Biomarker Assays, NULISA™ 250-plex Inflammation Panel, and Olink® Target 96 Inflammation Panel. These platforms differ in detection mechanism, target proteins, required volume per sample and output data (Table 1). MSD assays included 43 proteins, NULISA covered 246 proteins, and Olink had 92 proteins. The panels were selected to maximize the number of shared proteins across platforms and relevance for CD. The full list of proteins analyzed by each platform is provided in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 30 proteins were shared across the three platforms: TNF-α, IFN-γ, CXCL10, IL4, IL5, IL6, CXCL8 (IL8), CCL3, IL7, IL10, IL33, IL13, IL18, CCL4, CCL2, CCL13, CD274, TNFSF-10, CX3CL1, CCL8, CCL7, VEGFA, IL2, CXCL11, IL17A, MMP-1, TNFSF-14, CCL19, TNF-β,and CCL11. Additionally, MSD and NULISA shared 12 proteins which, however were not present in the Olink panel: IL16, IL22, IL23, Pentraxin 3, TNFSF-11, CSF2, IL1RN, IL15, CCL22, CCL17, IL12p70, and IL-1β. IL- 1α was shared only between MSD and Olink. In total 87 samples were collected. Due to differences in platform capacity (80 for MSD, 88 for Olink, and 83 for NULISA) by MSD 7,and by NULISA 4 samples were listwise excluded (the last samples on the list).

MSD analysis was conducted using the U-PLEX Custom Biomarker Assay, U-PLEX Custom Immuno-Oncology Group 1 Assay, and the V-PLEX Custom Human Biomarkers 1 panel (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, USA). These included Proinflammatory Panel 1, Chemokine Panel 1, and Cytokine Panel 1 sub-panels. The analysis was performed by the MSD QuickPlex SQ120. 50 µL per plate has been used for the analysis; 43 protein markers were distributed over 6 plates. Results were reported as absolute concentrations (pg/mL). The limit of detection (LOD, pg/mL) is defined as the mean signal of the blank plus 2.5 times its standard deviation and is calculated automatically for each run by the company’s software (Discovery Workbench). The analysis was conducted at local facility (Amsterdam UMC).

The NULISA™ 250-plex inflammation panel (Alamar Biosciences, Fremont, USA) was used for the analysis, the method is described in detail in previous studies7. The sample volume was adjusted from 10 to 30 µL to accommodate lower analyte concentrations. Data normalization involved adjusting target counts by internal controls and IPC normalization, followed by rescaling and log2-transformation to generate NULISA Protein Quantification (NPQ) units. (LOD, NPQ) is calculated by measuring the mean signal of the negative control and adding three times its standard deviation. The analysis was conducted at Alamar Biosciences, Fremont, CA, USA.

The Olink® Target 96 Inflammation panel (Olink Proteomics, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to analyze 92 proteins. Results were reported as Normalized Protein Expression (NPX) values on a Log2 scale. For the analysis 1 µL of sample was used. (LOD, NPX) is calculated as 3 times the standard deviation above the average of negative controls. The analysis was conducted at Olink Genomics CoFa, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Biomarker protein concentrations normalization for total protein amount

The amount of SC collected by a tape is variable and to account for this variability, protein marker levels are commonly normalized by total protein amount on the tape2. The total protein amount in the extract was determined using the Micro BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). For MSD, normalization involved dividing raw concentrations (pg/ml) by corresponding total protein concentrations, yielding levels expressed as pg biomarker/µg total protein. As recommended by the manufacturer, NULISA data (NPQ values), which were provided in log2 scale, were first transformed to linear scale (2^ (log2 value)) and 1 was subtracted. These linear values were then divided by the corresponding total protein concentration and multiplied by the across-sample per-target median. Finally, 1 was added to the corrected values, followed by log2 transformations. For Olink, which also reports values on a log2 scale (NPX), the same normalization approach as NULISA was applied, except without the subtraction and addition of 1. Specifically, values were transformed to the linear scale, normalized to total protein, adjusted using the per-target median, and then transformed back to the log2 scale.

Detectability

Assay detectability was defined as the percentage of samples with protein levels above the LOD, which was derived from the analytical run. A biomarker was considered detectable when more than 50% of samples were above the LOD. We assessed overall detectability which refers to the detectability of all protein markers included in the assay, as well as the detectability of shared protein markers: 30 proteins across all three platforms and an additional 12 proteins shared between MSD and NULISA, and one protein shared between MSD and Olink.

Statistical analysis

We report means with standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed parameters and medians with their interquartile (25th −75th percentile [IQR]) ranges.

MSD values were log2-transformed to ensure consistency with the other two platforms for the correlation and differential abundance analyses. To assess concordance between platforms we calculated the interclass correlation coefficients (ICC) from all three panels using a two-way mixed-effects model15. For pairwise correlations, Pearson correlation analysis was performed. Only samples with concentrations above the LOD were considered, reported zero concentrations were included only if the LOD in the assay was also specified as zero.

We also estimated the differential expression of proteins in the different skin conditions (ACD, ICD, and HD) vs. controls using a mixed effects model. This model also corrects for age and gender. In presenting the differences in protein expression in ACD, ICD and HD vs. control for each panel the model estimates were used to calculate protein distributions. The fixed effects distribution is therefore based on model estimates and does not represent the actual individual patient protein data. We have done this by modeling a normal distribution around the mean and SE. The interquartile range (IQR) is based on the 75th percentile-25th percentile calculated by qnorm in R. This IQR is used to estimate the upper and lower whiskers by 25th/75th percentile ± 1.5 * IQR.

All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 4.3.1 and RStudio version 2023.09.0. We repost p-values < 0.05 as significant.

Results

Characteristics of study samples and demographic data

Samples were collected from 28 patients. If a patient had positive patch test reactions to multiple allergens or to both an allergen and SLS, SCTS samples were taken from each individual positive reaction site. As a result, in these patients multiple SCTS samples were collected, corresponding to different types of skin reactions. In the allergen patch test, 28 of 33 patients had mild reactions (+), while 5 patients had stronger reactions (++). In total, 87 tape strips were collected across all participants. Samples from positive reactions to allergens were classified as ACD, while those from positive SLS reaction were classified as ICD. HD samples were from clinical cases with no confirmed etiology and may represent various types of dermatitis, including ICD, ACD, atopic dermatitis, or combitations thereof.

Baseline patient characteristics of participants, stratified by skin condition (ACD, ICD, HD) and control, are presented in Table 2. Total protein concentrations, which were used for normalization of biomarker concentrations, did not differ significantly between groups (Kruskal–Wallis test, p > 0.05).

Overall platform detectability

MSD demonstrated an overall detectability of 69.8% across its 43 measured proteins. NULISA showed a detectability of 28.5% across its 246 proteins while Olink exhibited the lowest detectability at 15.2% for its 92 proteins. Overall detectability and LOD’s of all analyzed proteins are listed in Supplementary Table 1. While subsequent data analyses focus on the 30 proteins shared across all three platforms to allow for direct comparison, we note that NULISA and Olink also detected several less commonly studied proteins in SCTS with high sensitivity. Beyond shared proteins, NULISA detected the following protein markers in 100% of samples: AREG, CEACAM5, CXCL14, HLA-DRA, IL19, IL36B, IL36G, LIF, S100A9, and TLR3. On the Olink platform, only three proteins, ADA, CST5, and uPA were detectable in more than 80% of samples. The MSD and Olink platforms uniquely included IL-1α, which was detectable in 100% of samples. These proteins, although not part of the shared set of proteins, may warrant further investigation due to their robust detectability and potential relevance to inflammatory skin conditions.

Detectability of shared protein markers across three platforms

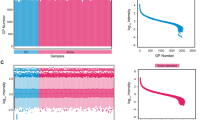

The detectability of the 30 shared proteins varied across the three compared platforms (Figs. 1A and 2). MSD had the highest detectability, detecting 21 of 30 proteins (70%). Detectability was 100% for nine proteins, including IL2, IL5, IL10, IL18, TNFSF-14, MMP-1, VEGFA, and CX3CL1.

NULISA achieved detection for 9 out of 30 shared proteins (30%). The platform showed the highest detectability for IL18 (86.8%), VEGFA (83.1%), and CXCL8 (80.7%).

Olink showed the lowest detectability among the three platforms, with only 5 out of 30 proteins being detectable (16.7%). The proteins with the highest detectability on this platform were VEGFA (94.3%), CXCL8 (85.6%), and MMP-1 (82.7%).

The detectability of the twelve proteins shared only by MSD and NULISA, but not Olink is shown in Fig. 2B. The detectability of IL- 1α, shared only between MSD and Olink, is shown in Fig. 1C. MSD detected 9 of 12 proteins, while only 4 proteins were detected by NULISA. IL- 1α had high detectability in both, MSD and Olink (Fig. 2C).

Detectability of protein markers across three platforms (Meso Scale Discovery (MSD), NULISA, and Olink) for (A) 30 shared proteins, (B) additional 12 proteins shared only by MSD and NULISA and C) one protein shared only between MSD and Olink. Protein detectability is shown as a percentage, with red bars representing detectable proteins (> 50%) and blue bars indicating non-detectable proteins (< 50%).

For visualization, detectability of 30 shared proteins for three platforms are shown as box plots (Fig. 3).

Correlation between three proteomics platforms

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis identified biomarkers with excellent agreement (ICC ≥ 0.75; e.g., CCL3, CXCL8, MMP-1, VEGFA), moderate agreement (ICC 0.40–0.74; e.g., CCL13, CCL19, CCL2, CCL4, CXCL10, CXCL11, IL6, TNF-α, IL17A, IL18, TNFSF-14), and low or non-significant agreement (ICC < 0.40, and/or p > 0.05; e.g., CCL11, CCL7, CCL8, CD274, IFN-γ, IL2, IL4, IL5, IL7, IL10, IL13, IL33, CX3CL1, TNF-β and TNFSF-10. The majority of proteins that showed strong agreement across the three platforms also had high detectability (Table 3).

The proteins with the highest ICC and good detectability including CXCL8, CCL3, VEGFA and MMP-1, showed consistently strong pairwise correlations as indicated by Pearson correlation coefficients across three platforms varying from 0,71 to 0.97 (Table 4).

Moderate to strong correlations in pairwise comparisons were observed for TNF-α, CXCL8, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL3, IL6, IL18, CCL4, CCL2, CCL7, CCL8, CCL13, CCL19, VEGFA, MMP-1, TNFSF-10, and TNFSF-14. However, for some proteins, correlations were lower for specific platform combination. For example, IL2, IL5, IL13, and IL33 showed a moderate correlation only between NULISA and MSD, but not across other two pairwise comparisons.

Approximately 50% of the proteins exhibited weaker correlations (r < 0.4), including IL4, IL7, IL10, CX3CL1, CCL11, and TNF-β. The majority of these proteins had low number of detectable samples (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, some proteins, such as IL6, TNF-α and CCL4 showed moderate to strong correlation despite of lower detectability, especially in Olink (e.g. respective detectability of these proteins was 13.8% 29.9%, 34%).

In Fig. 4 Pearson correlation coefficients (R) and corresponding significance levels (p) are shown as an illustration for two proteins with strong correlations and high detectability (CXCL8 and VEGFA), and for proteins with moderate to strong correlation despite detectability in less than 50% of samples (IL6 and CCL4).

Correlation analysis of protein levels between MSD, NULISA, and Olink platforms. Protein levels are shown as log2-transformed values. Plots are presented for CXCL8, VEGFA, IL6 and CCL4. Each plot includes the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and the corresponding p-value. In Supplementary Fig. 1, correlation analysis data are shown also for other proteins.

Differentially expressed proteins in ICD, ACD and HD vs. controls across three platforms

Mixed effects model analyses identified several proteins across platforms that were differentially expressed in ICD, ACD, or HD compared to controls, with consistently higher protein levels in the dermatitis samples. The highest number of differentially expressed proteins was found in ICD and HD, whereas ACD showed fewer differences and MMP-1 was the only protein with significantly different expression in ACD in only MSD, with a trend toward significance on the other two platforms.

Supplementary Table 2 shows the results of the fixed effect estimates, 95% CI and significance levels for all 30 protein markers and platforms.

Figure 5 visualizes the mixed-model results across all 30 shared proteins. Circles indicate proteins with > 50% detectability, while triangles indicate proteins detectable in ≤ 50% of samples. Symbols are only shown for proteins with significant differences (P < 0.05).

Across all platforms combined, 11 proteins showed significant differential expression, including both detectable and non-detectable proteins. CXCL8, MMP-1, and VEGFA showed consistent differential expression in ICD and/or HD across all three platforms, while other proteins were platform-specific, such as IL-18 (HD, MSD only) and IL-5 (ICD, NULISA only).

When considering platform-specific results, MSD identified 7 significant proteins (VEGFA, CXCL8, IL18, TNSF-14, MMP-1, CCL3 and CCL4), all detectable in > 50% of samples. NULISA identified 10 significant proteins (all in ICD), of which 4 were detectable in > 50% of samples (VEGFA, IL5, CXCL8 and CCL2), and 6 (TNSF-14, MMP-1, IL-13, CCL7, CCL3, and CCL4) were detectable in ≤ 50%. Olink identified 5 significant proteins, 3 detectable in > 50% of samples (VEGFA, MMP-1, CXCL8) and 2 (CCL3 and CCL4) detectable in ≤ 50%. Across all three platforms, fixed-effect estimates were positive, indicating upregulation in dermatitis-affected skin.

Heatmap summarizing mixed-effects model results for protein expression in HD, ICD, and ACD compared to controls across three analytical platforms (MSD, NULISA, Olink). The heatmap displays the estimated effect size for each protein (color scale). Symbols denote significant proteins (P < 0.05), indicating detectability: (filled circle) detectable in > 50% of samples, (filled triangle) detectable in ≤ 50% of samples.

Figure 6 presents boxplots as an illustration for CXCL8, VEGFA, IL18, CCL2, MMP-1 and IL5. These proteins showed differential expression in at least one condition (ICD, ACD, or HD). With the exception of IL5, which had low detectability on Olink (1.1%) and MMP-1 which had borderline detectability on NULISA (49.4%), other proteins were detectable in > 50% of samples across all three platforms. Notably, the pattern of increased expression for these proteins was similar across platforms, with higher levels consistently observed in ICD and HD.

Fixed effect estimates of protein expression differences between dermatitis groups (ICD, ACD, HD) and controls, based on the mixed model analysis. Each boxplot shows the distribution of estimated differences for CXCL8, VEGFA, IL18, CCL2, MMP-1 and IL5. The P-value gives the significance of the expression differences compared to control samples, as determined by the mixed effect model.

The calculated P-values throughout the manuscript were not adjusted for multiple testing. To assess whether our results may be driven by random chance, we constructed a quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot of observed versus expected p-values across all protein–platform–condition combinations, complemented by a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As shown in the Q–Q plot (Supplementary Fig. 2), the p-values closely followed the expected uniform distribution, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test yielded a p-value of 0.86. This indicates that the p-values do not significantly deviate from the null expectation, suggesting that the reported findings are unlikely to reflect systematic inflation of false positives.

Discussion

This study compared three multiplex immunoassay platforms, Meso Scale Discovery (MSD), NULISA, and Olink for their ability to detect inflammatory protein biomarkers in stratum corneum tape strips (SCTS) from both non-affected and dermatitis-affected skin. MSD demonstrated the highest detectability, identifying a broader range of proteins across samples. NULISA, and in particular Olink showed lower detectability for a majority of protein markers. However, for proteins with sufficient detection rates, all three platforms showed broadly consistent differential expression patterns between dermatitis-affected and non-affected skin, and correlations between platforms were generally strong. Given the growing use of SCTS as a minimally invasive method for skin biomarker analysis, these findings help inform the choice of appropriate platform in dermatological research.

Assay detectability

MSD showed the highest overall detectability in SCTS samples, followed by NULISA and Olink. Across all proteins measured by each platform, MSD achieved an overall detectability of 69.8% for its 43 proteins, while NULISA reached 28.5% across its 246 proteins, and Olink showed the lowest detectability at 15.2% for its 92 proteins. While a direct comparison of overall detectability is complicated by differences in the number and pre-selection of protein targets across platforms, analysis of the 30 shared proteins confirmed MSD’s highest sensitivity, detecting 70% of these targets. Moreover, approximately 50% of proteins were detected by MSD in more than 95% of samples, demonstrating its robustness. Several of these protein markers, including IL18, IL-1β, VEGFA, CXCL10,and CXCL8 were previously detected in SCTS in various skin conditions such as AD, CD,and skin cancer1,3,5,6,11,13,16. Notably, by MSD several additional markers, including members of TNF ligand family (TNFSF-10, TNFSF-11,and TNFSF-14), TNF-inducible gene 14 protein (Pentraxin 3) and transmembrane protein CD274, were identified in SCTS with a high detectability rate.

NULISA detected 30% of the shared proteins but showed high sensitivity for a smaller subset, including VEGFA, IL18, and CXCL8, with these proteins detectable in over 80% of the samples. Olink had the lowest sensitivity, and detected 16.7% of the shared proteins. Similar to NULISA and MSD, it demonstrated high detectability for VEGFA, IL18, and CXCL8, and for MMP-1.

These differences in detectability between platforms likely reflect technical factors such as immunoassay detection method and used antibodies. Notably, Feng et al.7 compared the same three platforms in blood samples from COVID-19 patients and reported a different sensitivity ranking: NULISA > MSD > Olink. This contrast may be due to sample type, as SCTS contains much lower protein concentrations and may introduce matrix effects that affect assay performance. The protein panels used also differed. A separate study using Olink reported a higher number of measured proteins in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab, using pre-selected Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease panels (353 proteins)12,17. However, detectability rates were not provided. That study also used a different extraction buffer and performed eight successive extractions compared to three in our protocol, potentially enhancing protein yield but limiting comparability. Protein yield is an important determinant of detectability in SCTS studies, and future work should systematically investigate how extraction conditions influence recovery and comparability across platforms. Difference in sample input volume between platforms is also a potential factor that could influence detectability. Olink uses as little as 1 µL per assay, NULISA 10–30 µL, and MSD 50 µL. However, both Olink and NULISA are PCR-based methods, which can achieve high sensitivity from very small inputs and are therefore less dependent on sample volume than non-PCR assays such as MSD (electrochemiluminescence detection).

Correlation across platforms

The pairwise Pearson correlation and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis demonstrated good comparability across the three platforms, especially for proteins with high detectability. Proteins such as CXCL8, IL18, VEGFA, and MMP-1 exhibited strong agreement (r = 0.71 to 0.97) across platforms, highlighting the reliability of these assays for well-detectable markers.

Moderate to strong correlations were observed for proteins like CCL2, CCL7, CXCL10, IL5, IL6, and TNFSF-10, though variability across platforms was noted for some proteins, such as IL5 and CCL7. Approximately 50% of the proteins showed weaker correlations (r < 0.5), particularly those with low detectability such as CCL11, CX3CL1, IL7, and TNF-β. Notably, IL10, a good detectable protein in NULISA and MSD, showed week correlations (r = 0.12), suggesting that platform-specific factors, such as antibody recognition or nonspecific binding correction10, may affect concordance between different platforms. On the other hand, some proteins such as IL6, CCL3, CCL4, CCL13, CCL19,and TNFSF-10 showed good correlations despite being detected in less than 50% of samples in NULISA and Olink. This suggests that even for proteins with some platform-specific variability in detectability, reliable comparability can still be achieved.

Good comparability between immunoassay platforms has also been reported in studies measuring blood biomarkers. However, similar to our study, results for low-detectable proteins were found to be less consistent9,10. In a study by Feng et al.7 where expression of blood biomarkers was compared across three platforms, larger differences in detectability corresponded to lower correlations, emphasizing the importance of platform sensitivity and good detectability for reliable cross-platform comparison.

Differential protein expression in dermatitis subtypes across platforms

Eleven of the thirty shared protein markers, including IL13, IL18, CXCL8, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, MMP-1, TNFSF-14, CCL7, VEGFA,and IL5 showed significantly different expression between control skin and skin affected by patch-induced ICD, ACD,or HD on at least one of the investigated platforms. Most of these protein markers are well established mediators of innate and Th-cell mediated immunity in inflammatory skin diseases and have previously been measured in SCTS as biomarkers in irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, disease severity, and treatment monitoring in atopic dermatitis1,3,4,5,11,13. MMP-1, CXCL8, CCL3, CCL4,and VEGFA were differentially expressed across all platforms in ICD and/or HD, supporting their potential as robust indicators of skin inflammation.

When restricting to proteins detectable in more than 50% of samples, MSD identified the highest number of significantly differentially expressed proteins, particularly in patch-induced irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and hand dermatitis (HD), detecting 7 protein markers. NULISA and Olink identified fewer differentially expressed biomarkers, although NULISA uniquely identified different expression of IL5 in ICD. When including proteins detectable in fewer than 50% of samples, MSD identified 7 significant proteins, NULISA 10, and Olink 5. These results demonstrate that the number of significantly expressed proteins, is strongly influenced by protein detectability.This finding aligns with previous comparative studies, such as that of by Feng et al.7 in COVID-19 patients, where differences in detectability translated into variability in platform results. Importantly, for proteins detectable in more than 50% of samples, expression patterns were highly consistent across platforms, supporting robust cross-platform correlation. For example, VEGFA, MMP-1, and CXCL8 showed both high ICC values and concordant differential expression across platforms. In contrast, TNFSF-14 showed relatively high correlation but inconsistent differential expression, likely due to poor detectability (Olink 40%, NULISA 24%, MSD 100%).

Notably, the largest number of differentially expressed proteins was observed in ICD, whereas in ACD, MMP-1 was the only protein significantly increased. Most ACD patients (28 out of 33) exhibited only mild patch reactions (+), which may partly explain the relatively low cytokine release. Consistently, higher levels of typical inflammatory markers such as VEGFA and CXCL8 were observed in ICD compared with ACD, reflecting stronger inflammation in ICD. This pattern likely reflects the biology of irritant responses, which are characterized by rapid barrier disruption and robust innate immune activation. In addition, response kinetics may contribute: irritant-induced inflammation develops quickly, whereas in ACD, adaptive T cell–derived cytokines may peak later and remain localized deeper in the skin, such that at the time of sampling (96 h after patch testing) they may not yet be detectable in the stratum corneum. Another possible explanation is variation in protein yield; however, we found no differences between skin conditions.

Practical considerations

NULISA and Olink enable the analysis of multiple biomarkers in a single run using small sample volumes (10–30 µL for NULISA and 1 µL for Olink), resulting in faster analysis and significantly smaller sample volumes. In contrast, MSD requires multiple runs to analyze a larger set of biomarkers (up to 10 protein markers per plate), demanding more time and sample volume (50 µL per plate). This may pose challenges in SCTS samples, where extraction buffer volume must be kept low to avoid excessive dilution. The number of samples per analytical run is similar across the platforms: up to 80 samples can be analyzed per run on MSD, 83 on NULISA, and 88 on Olink.

Notably, MSD is the only platform that provides absolute protein concentrations, which is particularly important when working with SCTS samples. The amount of stratum corneum collected per tape strip can vary considerably due to factors such as anatomical site, applied pressure, and the SC depth from which the strip is obtained1,3. Absolute quantification offers clear advantages for longitudinal studies and for comparisons with findings from other studies using different methodologies.

In terms of flexibility, NULISA offers limited customization through pre-configured biomarker panels, whereas Olink allows a moderate degree of customization. MSD provides the highest flexibility, supporting fully customizable plates, for tailoring assays to specific research needs. In this study we selected specific panels to maximize the number of shared proteins as possible across platforms. Unlike NULISA, Olink and MSD offer a broader range of pre-designed and customizable panels, which may be particularly advantageous for exploratory studies. It is important to note, however, that this is a rapidly evolving field; companies are continuously expanding their marker portfolios, enhancing panel customization options, and increasingly incorporating features such as absolute quantification. These developments may further influence platform selection in future studies.

Study strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study lies in the direct comparison of assay performance using the same biological material obtained from clinically relevant skin conditions. For cross-platform comparison, a substantial number of shared proteins were analyzed, including mediators with distinct immune signature, relevant to various skin diseases. This comparative approach provides valuable insights into platform’s detectability, and their ability to measure relevant immune markers. The study specifically focused on stratum corneum tape strip (SCTS) samples, a minimally invasive and easily accessible sample, highlighting its potential for dermatological researchers.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the conclusion that MSD demonstrated higher detectability applies specifically to SCTS samples from dermatitis patients and may not generalize to other diseases. Second, the study relied on predefined protein targets for each platform, which may constrain cross-platforms comparability. Nonetheless, all three platforms shared a set of 30 protein markers, which encompass a broad spectrum of immune responses, including Th1-, Th2-, and innate immunity pathways, known to play key roles in inflammatory skin diseases. Beyond these shared proteins, we also assessed and reported the detectability of the full panel available on each platform, which may be especially relevant for researchers considering these technologies for exploratory or biomarker discovery-oriented studies. Another limitation was the lack of anatomical location-matched control samples for HD, as it was often not possible to obtain unaffected skin from another hand. Instead, patch-test control samples from back skin were used, which may have influenced expression differences between dermatitis and control skin.

We did not perform sensitivity analyses to specifically assess potential site-related effects. As limit of detection (LOD) was automatically defined per run by each platform’s software, this may have influenced detectability outcomes, which were based on the proportion of samples exceeding these LODs. This cutoff was chosen because NULISA reports detectability using the same criterion, and similar studies have adopted this approach7,8. Although we did not test alternative thresholds, the > 50% cutoff represents a pragmatic balance between inclusiveness and robustness. Additionally, the same buffer was used for protein extraction across platforms, and no platform-specific matrix optimization was performed. ACD reactions were predominantly mild (+), and lower cytokine signals may therefore reflect reaction strength rather than a true absence of biomarker changes. Lastly, while the study primarily focused on detectability, it did not assess other parameters such as intra-assay precision, inter-assay variability, or platform reproducibility, which are essential for evaluating assay reliability and robustness18. Precision metrics for these platforms have been reported in vendor documentation (technical notes). Future studies incorporating direct assessment of reproducibility in SCTS samples will be important to complement our findings.

Conclusion

In this study, MSD provides better detectability in SCTS samples from dermatitis patients, whereas NULISA and Olink offered advantages in sample efficiency and throughput. Despite differences in detectability and quantification methods, all three platforms showed moderate to strong correlations for the majority of detected proteins, indicating consistency in protein expression across assays. Moreover, for proteins that were well detected across all platforms, the platforms demonstrated similar patterns of differential expression between control and dermatitis-affected skin.

Importantly, MSD was the only platform that provided absolute protein concentrations, enabling straightforward correction for total protein on the tape. This is essential when analyzing stratum corneum samples, especially given the variable amounts of protein collected by tape strips.

Measuring a broad range of inflammatory markers in non-invasive SCTS is of great importance, especially in occupational settings where distinguishing different subtypes of dermatitis will facilitate prevention and treatment. Our results highlight platform-specific strengths within the dermatitis context studied, though their generalizability to other diseases and biomarker panels requires further investigation. While promising, this work was primarily methodological and exploratory, and translation of these biomarkers into diagnostic settings will require further validation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

de Boer, F. L., van der Molen, H. F. & Kezic, S. Epidermal biomarkers of the skin barrier in atopic and contact dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 89, 221–229 (2023).

Keurentjes, A. J., Jakasa, I. & Kezic, S. Research techniques made simple: stratum corneum tape stripping. J. Invest. Dermatol. 141, 1129–1133.e1121 (2021).

Clausen, M. L., Kezic, S., Olesen, C. M. & Agner, T. Cytokine concentration across the stratum corneum in atopic dermatitis and healthy controls. Sci. Rep. 10, 21895 (2020).

Halling, A. S. et al. Skin TARC/CCL17 increase precedes the development of childhood atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151, 1550–1557e1556 (2023).

McAleer, M. A. et al. Topical corticosteroids normalize both skin and systemic inflammatory markers in infant atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 185, 153–163 (2021).

Rinnov, M. R. et al. Skin biomarkers predict development of atopic dermatitis in infancy. Allergy 78, 791–802 (2023).

Feng, W. et al. NULISA: a proteomic liquid biopsy platform with attomolar sensitivity and high multiplexing. Nat. Commun. 14, 7238 (2023).

Di Molfetta, G. et al. Inflammation biomarkers and Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study using NULISAseq. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst). 17, e70079 (2025).

McKinski, K., Tang, H., Wang, K., Birchler, M. & Wright, M. Comparison of highly sensitive, multiplex immunoassay platforms for streamlined clinical cytokine quantification. Bioanalysis 17, 17–29 (2025).

Zetlen, H. L. et al. Comparison of multiplexed protein analysis platforms for the detection of biomarkers in the nasal epithelial lining fluid of healthy subjects. J. Immunol. Methods. 517, 113473 (2023).

Brans, R., Jakasa, I., Goc, S., John, S. M. & Kezic, S. Stratum corneum levels of inflammatory mediators and natural moisturizing factor in patch test reactions to thiurams and fragrances and their possible role in discrimination between irritant and allergic reactions to Hapten mixtures. Contact Dermat. 84, 299–307 (2021).

He, H. et al. Tape-strip proteomic profiling of atopic dermatitis on dupilumab identifies minimally invasive biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 11, 1768 (2020).

Koppes, S. A. et al. Stratum corneum profiles of inflammatory mediators in patch test reactions to common contact allergens and sodium lauryl sulfate. Br. J. Dermatol. 176, 1533–1540 (2017).

Johansen, J. D. et al. European society of contact dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing - recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermat. 73, 195–221 (2015).

Shrout, P. E. & Fleiss, J. L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 86, 420–428 (1979).

de Boer, F. L. et al. Skin barrier- and immune response-related biomarkers of solar UVR exposure comparing indoor and outdoor workers. JID Innov. 4, 100280 (2024).

Olesen, C. M. et al. Tape-strips provide a minimally invasive approach to track therapeutic response to topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 9, 576–579.e573 (2021).

Van Gool, A. et al. Analytical techniques for multiplex analysis of protein biomarkers. Expert Rev. Proteom. 17, 257–273 (2020).

Funding

The funding for this study was provided by the Expertise Centre for Substance-related Occupational Diseases in the Netherland (Lexces), as part of a government-subsidized research initiative on the prevention of occupational diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK, HvdM and FdB were involved in conceptualization of the study. SK and NM prepared the draft manuscript. FdB, TR and NM were involved in patient diagnosis and/or sample collection. JV performed biomarker analysis. NM and WO performed statistical analysis. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Metwally, N.K.A., de Boer, F., Vreeken, J. et al. Comparison of three multiplex immunoassays for biomarker analysis in stratum corneum tape strips. Sci Rep 15, 40014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23579-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23579-7