Abstract

Sexist attitudes and the myth of romantic love have been studied as cognitive distortions associated with various inappropriate behaviors in adolescence, including gender violence. Despite this known link, no single instrument has been adapted for the adolescent population to assess both distortions simultaneously. The objective of this study was to construct an instrument for adolescents that captures the main cognitive distortions associated with sexism and romantic love myths. The sample comprised 493 students (47.7% boys, 51.3% girls) aged 13 to 18 (M = 15.17; SD = 0.53) from schools in northern Spain. The results revealed a differential pattern by sex in the presence of distorted thoughts, with a higher prevalence among male adolescents. The Scale of Cognitive Distortions in Adolescents (EDICA) consists of 17 items and shows excellent reliability (α = .922), with a two-factor structure corresponding to sexism and myths of romantic love. Therefore, the EDICA is a suitable instrument for estimating cognitive distortions in the adolescent population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cognitive distortions are defined as “systematic errors in… thinking… [that]… maintain the patient’s belief in the validity of his negative concepts despite the presence of contradictory evidence”1. Cognitive distortions are present in all individuals and can be defined as systematic biases that arise in response to specific situations, influencing the way both internal and external information is processed. Generally, these biases or distortions do not adhere to the principles of logic, probabilistic reasoning, or plausibility2. They interfere with perception and decision-making3 and perpetua pre-existing cognitive schemata4, which may be maladaptive or erroneous.

Evidence supports the integral role that cognitive distortions play in many psychological disorders in adults, especially in anxiety and depressive disorders5, potentially impairing an individual’s mental health and, consequently, their quality of life6,7. Similarly, modifying these dysfunctional thought patterns constitutes the core action of Cognitive Therapy, where the fundamental goal of this therapeutic approach is to restructure patients’ negative thoughts and help them interpret situations more healthily, thereby modifying the maladaptive schemata that contribute to their distress8,9.

Apart from the adult population, many authors have highlighted the influence of cognitive distortions in all phases of individuals’ lives, including youth and adolescents10. For example, evidence supports the presence of anxiety11, suicidal ideation12, behavioral concerns13 and medical conditions14, with cognitive distortions being a general risk factor in youth psychopathology15. In addition to various psychological pathologies, cognitive distortions have been studied within different interpersonal problems, particularly regarding their role in the emergence of gender violence behaviors, where they are identified as a risk factor contributing to both the onset and persistence of these actions16.

Among the cognitive distortions as explanatory factors for gender violence behaviors, those rooted in traditional roles that view women as inferior are particularly significant. Specifically, these distortions include questioning the existence of abuse, minimizing its effects, blaming the victim, and exonerating aggressors. These beliefs, which consider women inferior solely based on their sex, are traditionally categorized as sexism17 and encompass various attitudes and thoughts asserting that men and women are fundamentally different and should hold distinct roles and social norms18.

According to the Theory of Ambivalent Sexism19, two distinct forms of sexism coexist: hostile and benevolent sexism. Hostile sexism involves overt antipathy toward women and emphasizes their supposed inferiority. Conversely, benevolent sexism portrays women in a traditional role, which often elicits seemingly prosocial behavior but is equally discriminatory. This latter form of sexism emphasizes the protection men are perceived to provide to women, based on stereotypical views, which can thus have harmful consequences20. Research examining sexism toward women has consistently reported that the outcomes of the benevolent component can be even more harmful than those of hostile sexism. This paradox occurs primarily because benevolent sexism is less recognizable as prejudice, making it more challenging to address and ultimately eliminate21.

In addition to the possible distortions related to sexism in the adolescent population, a biased perception of love often develops. Consequently, beliefs and attitudes that predict gender-based violence become normalized22 and are shaped within the so-called myths of romantic love23. Diverse research has identified the most influential myths related to romantic love24,25,26 including: omnipotence (love conquers all); exclusivity and fidelity (a person in love cannot be attracted to others); pairing up (being in a relationship is necessary for ultimate happiness); the “better half” or “soulmate” (choosing a predestined partner requires extra effort, fostering dependence); free will (love is an uncontrollable, internal, and personal feeling, unaffected by external influences like social factors); possession and jealousy (jealousy is an indicator, and even a necessity, of true love); and marriage (genuine love must culminate in cohabitation). Despite their prevalence, these myths are fictitious, misleading, and illusory, and they are impossible to fulfil25. Women learn a way of loving that can lead them to devalue themselves as independent people and accept their existence in a self-sacrificing manner to the other27. Adherence to these myths presents gender differences, with boys identifying more with the myths of omnipotence and ambivalence, while girls tend toward idealization with myths such as eternal passion28,29. The persistence of these beliefs in the adolescent population is critical, as it is directly associated with the normalization and minimization of dating violence28,29,30.

Teen dating violence is a highly prevalent problem among European youth, with particular concern in Spain, where an increase has been observed since 2017 in young people reporting having suffered violence within their romantic relationships31. Studies in this age group indicate that traditional forms of gender violence, characterized by physical attacks, have been increasingly replaced by emotional or psychological attacks, often facilitated by new technologies32. Prevalence data for physical violence among dating partners are situated around 30%33, reaching as high as 57.5% in some surveyed populations34. The same authors have observed an even higher prevalence of psychological and emotional violence, with figures reaching 95.5%. Additionally, acts of sexual violence are reported, with approximately 50% of participants claiming to have been victims of such aggression by their partners35.

Acts of violence using digital platforms or technological means have become highly relevant in the context of partner violence. Perpetrators use these means to victimize at rates ranging between 5.8% and 92%36. This latter typology of gender violence, conducted through digital media, has been identified in various studies as the most frequent form of direct aggression and control, and appears to be more accepted by the young population37.

A robust body of research now clearly demonstrates the connection between teen dating violence and adverse health consequences, both immediate and long-term38. The most immediate outcomes include the potential for physical injury39,40 and, in extreme cases, homicide41. In the long term, this violence is associated with increased internalizing symptoms (such as anxiety and depression), suicidal ideation, substance use, and re-victimization38.

The presence of gender violence behaviors among adolescents, including the persistence of discriminatory attitudes in this increasingly younger age group42, justifies the need for studies that analyze the origin and the determinants of these behaviors. Such research is crucial for designing effective prevention strategies for this population. A positive relationship has been observed between the acceptance of these beliefs and attitudes and the emergence of gender violence behaviors43,44.

The influence of cognitive distortions related to sexism and myths of romantic love on the emergence and persistence of gender violence behaviors in the adolescent population justifies the need for a specific measurement instrument adapted to young individuals. Currently, such an instrument is not available in the existing tools. Therefore, the present study sought to build a measurement instrument that collects the most frequent cognitive distortions associated with sexism and myths of romantic love among adolescents. The second objective of this study was to analyze the presence and behavior of cognitive distortions in a group of Spanish adolescents and to examine how these distortions vary according to the participants’ sex.

Based on the theoretical frameworks it is expected to observe differences depending on the sex of adolescents in the presence of distorted thoughts related to sexism and myths of romantic love, with a higher score in male adolescents. Moreover, a significant and positive association is expected between the presence of distorted thoughts and behaviors typical of gender violence, regardless of the sex of the adolescents.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The sample comprised 493 students aged between 13 and 18 years, age of 15.17 years (SD = 0.53). There were no significant differences in the average age based on sex (see Table 1).

Of the total participants, 47.7% (235 participants) were boys, and 51.3% (253 participants) were girls, with 1% (five cases) of the participants not providing information on this aspect.

Regarding the sentimental situation of adolescents, 50.3% of the participants claimed that they had never had a partner, 18.9% had a partner when answering the evaluation questionnaire, and 26.4% claimed to have had a partner in the past; however, in the actual moment, they do not have a stable romantic relationship. The remaining participating adolescents (4.4%) reported that the emotional relationships they had or were in at the time of completing the research questions were sporadic, not considered stable couples or courtships.

For data collection, the scale was digitized using Google Forms. Before collecting the participants’ data, informed consent was obtained from all parents after providing them with information on the objectives of the intervention, the instruments used, and the sociodemographic data required. Information on the research objectives, research team, and data protection compliance clause was included on the first page of the questionnaire to obtain consent from the minors. n addition to providing informed consent, participants must agree to the research objectives and the confidentiality of their data. No personal data that could lead to participant identification was collected. This study complied with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Researchers (PI080/2024), as well as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights (LOPDGDD). The researchers were present in the classrooms during the scale application, fully explaining the items and ensuring no one responded without understanding the questions.

Measures

Cognitive distortions scale related to gender violence (Escala de Distorsiones Cognitivas Adolescentes; EDICA)

The Cognitive Distortions in Adolescents Scale (EDICA) is a self-report psychometric instrument designed to assess dysfunctional thinking patterns in adolescents. The scale presents a series of statements covering various thought, action, and feeling patterns, requiring respondents to indicate their degree of agreement using a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = Totally Disagree to 4 = Totally Agree). The instrument explicitly assures anonymity and stresses that there are no correct or incorrect answers, promoting honest self-disclosure. The content of the EDICA scale focuses particularly on two main areas of distortion: gender-based stereotypes and maladaptive relational beliefs. Items targeting gender stereotypes assess adherence to traditional roles (e.g., “Girls are more sensitive than boys” or “There are jobs that are typical for boys and others for girls”), where items concerning relationships evaluate distorted beliefs about control, trust, and jealousy in romantic partners (e.g., “One way to take care of your boyfriend/girlfriend is to worry about knowing where he is and with whom” or “Trust in your boyfriend/girlfriend is demonstrated by revealing your social media passwords.”) (Appendix 1).

The final instrument configuration was established through the following detailed, sequential steps:

-

1.

Initial Literature Review and Item Generation: The process began with a comprehensive analysis of existing literature concerning instruments used to estimate sexist traits in both adult and adolescent populations. This phase also included a review of the characteristics of the myth of romantic love in young adults and its influence on the emergence and severity of dysfunctional behaviors. The findings from this initial research phase culminated in the generation of 22 preliminary statements that were deemed representative of the target phenomenon.

-

2.

Qualitative Validation via Focus Groups: To ensure the clarity and relevance of the preliminary items, two structured discussion groups were conducted with 20 adolescents aged 13–18 years. These participants were presented with the 22 statements to provide qualitative feedback regarding their representativeness within the adolescent population. The goal was to assess the clarity of the language and expressions used, as well as to identify and implement any necessary stylistic adjustments to facilitate accurate and reliable responses.

-

3.

Psychometric Evaluation and Final Testing: In the final phase, the original 22-statement scale—now refined based on the qualitative input—was administered to the study’s primary adolescent sample. This quantitative step was essential for analysing the instrument’s reliability (consistency) and concurrent validity (correlation with other established measures). To achieve this objective, the scale’s results were evaluated against data collected from the additional assessment instruments detailed later in this study.

Inventory of distorted thoughts about women and the use of violence (IPDMUV)

It is a measurement instrument that assesses the cognitive component of sexism and violence as a problem-solving strategy. It was initially designed for clinical practice45,46,47, although without psychometric guarantees as part of a cognitive behavioral program for treating abusers.

Two studies validated this instrument using Spanish sample groups. The first one48 administered the IDTWV to 1.395 university students after modifying the response system (from true–false to a four-point Likert-type scale). These authors also eliminated five items from the original scale. They grouped the remaining items into four dimensions, achieving a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. The main limitation of this study was that the sample group was composed exclusively of university students, with almost two-thirds of the participants being women.

In addition to the previous study, the inventory was validated once again49 with 180 inmates convicted of intimate partner violence. Several items were eliminated due to either their low factor loadings, their limited contribution to the scale’s consistency, or the fact that their wording was confusing. The factor solution is similar to that proposed previously48, with an alpha of 0.76. This second study also had several limitations: the sample group was comprised exclusively of incarcerated abusers, without a control group, social desirability bias was not controlled for; and convergent validity was not established.

A final revision of the scale47 proposed the Inventory of Distorted Thoughts about Women and the Use of Violence-Revised (IPDMUV-R), which is a unidimensional scale consisting of 21 binary items (true or false). This instrument allows for the identification of aggressors’ irrational beliefs related to gender roles and the supposed inferiority of women concerning men, as well as the use of violence as an acceptable way to resolve conflicts. The instrument met the criteria established by international standards, and its reliability, as evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.74. The greater the number of affirmative answers, the greater the number of cognitive distortions about women and the greater the use of violence. Eight points were proposed as a cut-off for discriminating aggressors (or potential aggressors) from non-aggressors.

In the study conducted by Ubillos-Landa et al.44 the latest version of the instrument was used in a Likert-type response format with four options. This instrument was administered to Spanish adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years. Based on a sample of 2.919 adolescents, the authors proposed a model comprising two factors: 1) Factor 1 (F1): Stereotyped beliefs about women. 2) Factor 2 (F2): Beliefs about violence, including blaming women and accepting violence while exculpating the aggressor. The reliability indices of the proposed model were high for both the original scale (α = 0.85) and for the factors of stereotypes about women (α = 0.88) and beliefs about the use of violence (α = 0.78), as well as a high correlation between this scale and the instruments proposed for its concurrent validation.

Adolescent gender-based violence scale (Escala de violencia de género en adolescentes: ESVIGA)50

An instrument made up of 26 statements that adolescents must complete in a Likert-type response format with five response options that reflect the frequency with which they have carried out behaviors considered gender violence. The scale is configured to cover the main behaviors of adolescent violence (cyber violence, physical violence, verbal violence, psychological violence, and sexual violence) both from the perspective of the aggressor (violence committed) and from the point of view of a possible victim (violence suffered). The internal consistency of the scale demonstrated high reliability across the overall scale (α = 0.965), as well as in the subscales of violence committed (α = 0.935) and violence suffered (α = 0.929).

Data analysis

Data analysis began with exploratory factor analysis using the principal component method and varimax rotation. The KMO and Bartlett tests were employed to assess the hypotheses concerning the adequacy of the factorial model and evaluate the validity of the construct.

Once a factorial solution was obtained, the resulting scale’s reliability was analyzed using Cronbach’s alpha statistic for both the entire scale and the subfactors detected during the exploratory analysis. The scale’s correlations with the Inventory of Distorted Thoughts about Women and the Use of Violence—Revised (IPDMUV-R) and the Gender Violence Scale among Adolescents (ESVIGA) were subsequently analyzed. Pearson correlations were utilized to estimate concurrent validity.

Results

Descriptive results

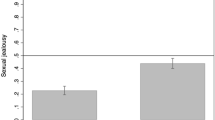

The descriptive results obtained in the sample indicate that adolescents show the highest degree of agreement with two statements related to prejudices about sex differences: “Girls are more sensitive than boys” and “Girls are cleaner than boys.” Simultaneously, within the factor that includes myths of romantic love, the statement on which adolescents agree to a greater extent, regardless of their sex, is: “If your partner does not let you see their phone, it is because they are hiding something.” Significant differences depending on sex were observed in all the statements included in the instrument, with boys aged between 13 and 18 years showed a higher degree of agreement than girls of the same age, and where only the statement that “Boys are unfaithful by nature” did not show sex differences (see Table 2).

Exploratory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis of the 22 items of the original scale yielded a factor structure comprising two factors, accounting for 51% of the variance. Although the statistical result was favorable (KMO = 0.952; p < 0.001), there were items whose factorial weights in the rotated component matrix were distributed equally between the two factors, failing to adjust correctly to the observed factorial distribution.

Eliminating the items that did not fit the factors obtained, a final solution was obtained, composed of 17 statements that maintained the good statistical results observed for the original scale (KMO = . 946; p < 0.001), increasing the total explained variance up to 56%, this percentage being equally distributed between the two factors (see Table 3).

The distribution of the items indicated in the previous table differentiates the first factor, which accounts for 29% of the variance observed in the data obtained. This factor comprises statements that denote prejudices regarding the differences between men and women (girls are cleaner than boys), or that make assertions based on sex differences between adolescents (some works are specific to boys and others to girls). All statements can be included within a factor called sexism or sexist statements. The second factor, explaining 27% of the observed variance, makes statements related to couple relationships (trust in your partner is demonstrated by revealing your social network passwords; if your partner does not feel noisy when they see you talking to another, he does not like you), fulfilling the characterization of being statements that include the so-called myth of romantic love present in adolescent relationships.

Reliability analysis

The results obtained from the reliability analyses of the scale showed good reliability for the entire instrument (α = 0.922), including the factors associated with sexism (α = . 896) and myths of romantic love (α = 0.882).

The results of the reliability analysis showed that eliminating any item did not improve the instrument’s overall reliability, suggesting that all statements have a significant contribution to the validity of the final scale (see Table 4).

Concurrent validity

The revised version of the Inventory of Distorted Thoughts about Women and the Use of Violence—Revised (IPDMUV-R) and the Committed Violence subscale of the Adolescent Gender-Based Violence Scale (ESVIGA) were used to analyze the concurrent validity of the instrument. A strong correlation was found (r = 0.804; p < 0.01) between the global scores of the EDICA and the IPDMUV-R, a finding that also encompasses the subfactors of both scales. Of particular relevance, the most significant correlation (r = 0.713; p < 0.01) exists between the “Sexism” factor of the EDICA and the “Use of Violence” factor of the IPDMUV-R.

Finally, significant correlations were observed in the global scores of the EDICA and the ESVIGA violence-committed subscale (r = 0.280; p < 0.01) but also in the respective factors of sexism (r = 0.926; p < 0.01) and myths of romantic love in adolescence (r = 0.880; p < 0.01; see Table 5).

Discussion

The results indicate a greater prevalence of sexism-related cognitive distortions among adolescent boys. This finding aligns consistently with prior research that has reported higher levels of both hostile and benevolent sexism in male populations, including university students51 and adolescents19,29,52. This pattern is further supported by studies demonstrating that boys score higher on statements associated with romantic love myths29. The Social Role Theory of Gender53,54 explains this phenomenon, positing that while female gender roles have evolved, the rigidity of traditional male stereotypes and expectations has remained relatively stable. This stability limits male acceptance of non-traditional social roles, thereby motivating the maintenance of traditional or sexist cognitive schemata.

Recent results55 have indicated the influence of existing beliefs on different forms of sexual violence through technology (technology-facilitated sexual violence; TFSV), with an increase in the justification of violence56 and a higher propensity for perpetration57. Additionally, during the last few decades, existing beliefs have been considered a relevant vulnerability factor for the perpetration and victimization of violence58, being considered one of the main backgrounds in the justification and promotion of dating violence59, regardless of the partner’s sex60.

Regarding the variable called myths of romantic love, this variable has been related to the presence of gender violence, with results indicating that the more participants adhere to romantic love, the more they blame the victim and exonerate the perpetrator29,61. The presence of distorted thoughts related to the myths of romantic love is especially problematic in the adolescent population, where, in addition to being frequent, it has been pointed out as a variable that decreases their awareness of some abusive behaviors—expressly indicated as a form of dating violence28. The joint presence of sexism and myths of romantic love in adolescence has been pointed out as an essential risk factor for the appearance of gender violence. Some studies62 have indicated that the presence of these variables increases and maintains violence between adolescent couples.

In the previous context, EDICA is a quick and reliable instrument for estimating distorted thoughts related to sexism and myths of romantic love in adolescents, with higher reliability than the instruments available to date. These distorted thoughts are estimated to occur in isolation in the youth population. The nine statements that make up the sexism factor present optimal psychometric results concerning the scales used to date44, and the eight statements that make up the factors associated with the myths of romantic love show reliable results, with better results from scales specifically designed to measure this construct61.

The 17 statements that comprise the scale demonstrate good reliability. Furthermore, they explain the variance observed in the adolescent population, with concurrent validity results indicating the association between this instrument and its factors and other validated instruments for the adult population. These include the appearance of behaviors considered adolescent gender violence.

Beyond the results obtained, this study has limitations that should be considered future research. The first limitation is related to the sample employed, which was small and obtained through accessibility or convenience sampling, restricted to adolescents enrolled in schools in northern Spain. This convenience sampling method yields a normative sample lacking clinical or psychopathological features, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results to socio-cultural contexts distinct from those previously described.

The second limitation is associated with the scales used for the concurrent validation of the instrument. Inventories were employed that, while having been validated in the adolescent population, were originally designed and constructed for the clinical adult population treated for gender violence. The use of tools with a clinical and adult focus as a basis for validating a scale oriented toward the general adolescent population could introduce bias or limitations in the precision with which the new instrument’s validity is estimated.

This last limitation was the primary objective to be addressed, which was pursued when developing the current research, as there are no instruments specifically designed for the adolescent population that address cognitive distortions related to gender biases. Hence, it was necessary to make the comparison with instruments that have already been verified to estimate that same variable in the adult population, and which have also shown their association with gender violence in that population.

In addition to the limitations noted regarding the sample and the choice of instruments, the statistical analyses performed are limited to an exploratory factor analysis to determine the scale’s structure, yielding a two-factor distribution that should be further tested with an independent sample through a confirmatory factor analysis. Furthermore, no analysis could be performed to evaluate the temporal stability of the instrument, which is crucial for validating of a new scale.

Finally, it is worth noting that the research addresses sensitive topics, such as sexism and gender violence, through self-report questionnaires, where the confidentiality of the data obtained is guaranteed; however, a social desirability effect may still occur. Participants may tend to respond in the way they consider socially more acceptable or ‘correct’ instead of honestly reflecting their beliefs, which could have affected the accuracy of the means obtained.

The aforementioned limitations do not detract from the obtained results; yet, they pave the way for future lines of research that can be conducted using the newly developed instrument, with the most immediate being those that address the previously noted limitations.

It would be desirable to immediately continue expanding the sample to diverse sociocultural contexts, both nationally and those of Latin American origin, to corroborate the two-factor structure (sexism and myths of romantic love) derived from the exploratory factor analysis. Furthermore, conducting longitudinal studies would enable the evaluation of the instrument’s temporal stability and test–retest reliability, as well as the collection of data on the evolution of distorted thoughts in adolescents over time. These studies also include the possibility of analyzing the predictive capacity of the EDICA regarding the onset or persistence of dating violence behaviors, in both perpetrators and victims. It is noteworthy that, beyond the observed association between cognitive distortions in adolescents and gender violence at this age, other lines of research could include the association of cognitive distortions with sexual risk behaviors such as sexting and pornography consumption among youth, which currently pose significant challenges.

Finally, a vast area for future investigations may encompass the relationship between cognitive distortions and internalizing psychopathology (anxiety and/or depression) as well as externalizing behavioral problems, following the research trajectory that links cognitive distortions with various psychological pathologies. It would also be relevant to study its relationship with variables such as experience in relationships, exposure to violence, or consumption of media content with sexist or romantic overtones.

The construction and validation of the Cognitive Distortions in Adolescents Scale (EDICA) extend beyond a mere academic exercise, carrying significant practical implications for the detection and prevention of maladaptive behaviors, particularly gender-based violence, within the school environment. This reliable and valid instrument is positioned as a rapid and effective tool for professionals (such as counselors, psychologists, and educators) to identify specific cognitive distortions in the adolescent population related to sexism and the myths of romantic love.

The early identification of youth with high scores on these factors enables educational centers to design and implement early interventions aimed at modifying thought patterns before they escalate into problematic behaviors. Furthermore, the EDICA is essential as a pre- and post-test measure to evaluate the efficacy of school prevention programs, providing quantifiable data on the reduction of adherence to these distorted beliefs.

The established association between these distorted thoughts and gender violence underscores the urgency of focusing preventive actions on the adolescent population. These actions must be aimed at decreasing the presence of these variables in both aggressors and potential victims, thus facilitating the early identification of warning signs that prevent this form of violence from occurring and persisting into adulthood.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B. & Emery, G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression (Guildford Press, 1979).

Korteling, J. E. & Toet, A. Cognitive Biases. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, (2nd ed.) 610–619, Elsevier, (2020).

Balzan, R. P. & Moritz, S. Cognitive biases and psychosis: From bench to bedside. Schizophr. Res. 223, 368–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.07.014 (2020).

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S. & Weishaar, M. E. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide (Guilford Press, 2003).

Beck, A. T. & Haigh, E. A. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734 (2014).

Leahy, R. Cognitive Therapy Techniques: A Practitioner’s Guide (Guilford Press, 2017).

Dobson, D. J. G. & Dobson, K. S. Avoidance in the clinic: Strategies to conceptualize and reduce avoidant thoughts, emotions, and behaviors with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Pract. Innov. 3(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000061 (2018).

Gloaguen, V., Cottraux, J., Cucherat, M. & Blackburn, I. M. A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 49(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00199-7 (1998).

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T. & Fang, A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 (2012).

Pace, U., D’Urso, G. & Zapulla, C. Hating among adolescents: Common contributions of cognitive distortions and maladaptive personality traits. Curr. Psychol. 40, 3326–3331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00278-x (2019).

Buğa, A. & Kaya, İ. The role of cognitive distortions related academic achievement in predicting the depression, stress and anxiety levels of adolescents. Int. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 9(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.1000210 (2022).

Naderi, H., Alizadeh, S., Alipour, Z., Mahdizadeh Azdin, S. & Khalilnezhad, M. Negative spontaneous thoughts and depression in adolescents with suicidal ideation: Mediating role of cognitive distortion and cognitive flexibility. Int. J. Health Stud. 9(4), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.22100/ijhs.v9i4.1075 (2023).

Panourgia, C. & Comoretto, A. Do cognitive distortions explain the longitudinal relationship between life adversity and emotional and behavioural problems in secondary school children?. Stress Health J. Int Society For The Investigation Of Stress 33(5), 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2743 (2017).

Arabameri, F. & Khodabakhshi-koolaee, A. The role of early maladaptive schemas on coping styles and fear of recurrence in women with breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. Multidiscip. Cancer Investig. 5(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.30699/mci.5.4.578-1 (2021).

Barriga, A. Q., Landau, J. R., Stinson, B. L., Liau, A. K. & Gibbs, J. C. Cognitive distortion and problem behaviors in adolescents. Crim. Justice Behav. 27(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854800027001003 (2000).

Gracia, E., Rodriguez, C. M., Martín-Fernández, M. & Lila, M. Acceptability of family violence: Underlying ties between intimate partner violence and child abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 35(17–18), 3217–3236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517707310 (2020).

Gutierrez, B. C. & Leaper, C. Linking ambivalent sexism to violence-against-women attitudes and behaviors: A three-level meta-analytic review. Sex. Cult. Interdiscip. Q. 28(2), 851–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10127-6 (2024).

Rollero, C. & De Picolli, N. Myths about intimate partner violence and moral disengagement: An analysis of sociocultural dimensions sustaining violence against women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(21), 8139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218139 (2020).

Glick, P. & Fiske, S. T. The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491 (1996).

Rivas-Rivero, E., Checa-Romero, M. & Viuda-Serrano, A. Factores relacionados con las creencias distorsionadas sobre las mujeres y la violencia en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria. Rev. Educ. 395, 363–389. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-395-517 (2022).

Barreto, M. & Doyle, D. M. Benevolent and hostile sexism in a shifting global context. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 98–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00136-x (2023).

Galende, N., Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Jaureguizar, J. & Redondo, I. Cyber dating violence prevention programs in universal populations: A systematic review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S275414 (2020).

Gómez Perea, L. & Viejo, C. Mitos del Amor romántico y calidad en las relaciones sentimentales adolescentes. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. 13(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.33881/2027-1786.rip.13114 (2020).

Yela, C. La otra cara del amor: mitos, paradojas y problemas. Encuentros Psicol. Soc. 1(2), 263–267 (2003).

Ferrer, V., Bosch, E. & Navarro, C. Los mitos románticos en España. Bol. Psicolog. 99, 7–31 (2010).

Pascual, A. Sobre el mito del amor romántico. Dedic. Rev. Educ. Humanid. 10, 63–78 (2016).

Rivas-Rivero, E. & Bonilla-Algovia, E. Salud mental y miedo a la separación en mujeres víctimas de violencia de pareja. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 11(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2020.01.035 (2020).

Ruiz-Palomino, E., Ballester-Arnal, R., Giménez-García, C. & Gil-Llario, M. D. Influence of beliefs about romantic love on the justification of abusive behaviors among early adolescents. J. Adolesc. 92(1), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.09.001 (2021).

Bonilla-Algovia, E., Carrasco Carpio, C., Rivas-Rivero, E. & Izquierdo-Sotorrío, E. The scale of myths of romantic love: Psychometric properties and gender differences in Spanish adolescents. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 41(6), 1533–1553. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075241228767 (2024).

Cislaghi, B. & Heise, L. Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociol. Health Illn. 42(2), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13008 (2020).

Sanmartín, A., Gómez, A., Kuric, S. & Rodríguez, E. Barómetro Juventud y Género 2023. Cent. Reina Sofía de Fad Juventud https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10144131 (2023).

Rodríguez-Castro, Y., Martínez-Román, R., Alonso-Ruido, P., Adá-Lameiras, A. & Carrera-Fernández, M. V. Intimate partner cyberstalking, sexism, pornography, and sexting in adolescents: new challenges for sex education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(4), 2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042181 (2021).

Wincentak, K., Connolly, J. & Card, N. Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychol. Violence 7(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040194 (2017).

Rubio-Garay, F., López-González, M. A., Carrasco, M. A. & Amor, P. J. The prevalence of dating violence: A systematic review. Psycholog. Pap. 38(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2831 (2017).

Duval, A., Lanning, B. A. & Patterson, M. S. A systematic review of dating violence risk factors among undergraduate college students. Trauma Violence Abuse 21(3), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018782207 (2020).

Caridade, S., Braga, T. & Borrajo, E. Cyber dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggress. Violent. Beh. 48, 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.018 (2019).

Linares, R. et al. Cyber-dating abuse in young adult couples: Relations with sexist attitudes and violence justification, smartphone usage and impulsivity. PLoS ONE 16(6), e0253180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253180 (2021).

Piolanti, A., Waller, F., Schmid, I. E. & Foran, H. M. Long-term adverse outcomes associated with teen dating violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics 151(6), e2022059654. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-059654 (2023).

Exner-Cortens, D., Camacho Soto, J. N., Yeates, K. O., van Donkelaar, P. & Craig, W. M. The association between teen dating violence and concussion. J. Adolesc. Health 75(6), 939–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.07.019 (2024).

Reidy, D. E. et al. In search of teen dating violence typologies. J. Adolesc. Health 58(2), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.028 (2016).

Adhia, A., DeCou, C. R., Huppert, T. & Ayyagari, R. Murder–suicides perpetrated by adolescents: Findings from the national violent death reporting system. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 50(2), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12607 (2020).

León, C. M. & Aizpurúa, E. ¿Persisten las actitudes sexistas en los estudiantes universitarios? Un análisis de su prevalencia, predictors y diferencias de género. Educ. XXI 23(1), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.23629 (2020).

Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., Redondo, N., Olmos, R. & Ronzón-Tirado, R. Intimate partner violence among adolescents: Prevalence rates after one decade of research. J. Adolesc. 95(1), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12108 (2023).

Ubillos-Landa, S., Goiburu-Moreno, E., Puente-Martínez, A., Pizarro-Ruiz, J. P. & Echeburúa-Odriozola, E. Evaluación de pensamientos distorsionados sobre la mujer y la violencia de estudiantes vascoparlantes de enseñanzas medias. Rev. Psicodidáct. 22(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1136-1034(17)30037-0 (2017).

Echeburúa, E. & Fernández-Montalvo, J. Tratamiento cognitivo-conductual de hombres violentos en el hogar: un estudio piloto. Anál. Modif. Conduct. 23(89), 356–384 (1998).

Echeburúa, E., Amor, P. J. & Corral, P. Hombres violentos contra la pareja: trastornos mentales y perfiles tipológicos. Pensam. Psicológ. 6(13), 27–36 (2009).

Echeburúa, E., Amor, P. J., Sarasua, B., Zubizarreta, I. & Holgado-Tello, F. P. Inventario de pensamientos distorsionados sobre la mujer y el uso de la violencia - revisado (IPDMUV-R): Propiedades psicométricas. An. Psicolog. 32, 837–846. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.231901 (2016).

Ferrer, V., Bosch, E., Ramis, C., Torres, G. & Navarro, C. La violencia contra las mujeres en la pareja: Creencias y actitudes en estudiantes universitarios/as. Psicothema 18(3), 359–366 (2006).

Loinaz, I. Distorsiones cognitivas en agresores de pareja: Análisis de una herramienta de evaluación. Ter Psicológ. 32(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082014000100001 (2014).

Penado-Abilleira, M. & Rodicio-García, M. L. Development and validation of an adolescent gender-based violence scale (ESVIGA). Anu. Psicolog. Juríd. 28(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2018a10 (2018).

Esteban Ramiro, B. & Fernández Montaño, P. Young people have sexist attitudes?: Exploration of ambivalent sexism and neosexism in university students. Femeris 2(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.20318/femeris.2017.3762 (2017).

Rodríguez-Castro, Y., Lameiras-Fernández, M., Carrera-Fernández, M. V. & Vallejo- Medina, P. La fiabilidad y validez de la escala de mitos hacia el amor: Las creencias de los y las adolescentes. Rev. Psicolog. Soc. 28(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1174/021347413806196708 (2013).

Eagly, A. H. & Wood, W. Social role theory. In Handbook of theories of social psychology (eds Van Lange, P. A. M. et al.) (Sage Publications Ltd, 2012). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n49.

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M. & Sczesny, S. Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am. Psychol. 75(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494 (2020).

Martínez-Bacaicoa, J., Real-Brioso, N., Mateos-Pérez, E. & Gámez-Guadix, M. The role of gender and sexism in the moral disengagement mechanisms of technology-facilitated sexual violence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 152, 108060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108060 (2024).

Sánchez-Hernández, M. D., Herrera-Enríquez, M. C. & Expósito, F. Controlling behaviors in couple relationships in the digital age: Acceptability of gender violence, sexism, and myths about romantic love. Psychosoc. Interv. 29(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a1 (2020).

Pina, A., Holland, J. & James, M. The malevolent side of revenge porn proclivity: Dark personality traits and sexist ideology. Int. J. Technoethics 8(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJT.2017010103 (2017).

Marcos, V., Gancedo, Y., Castro, B. & Selaya, A. Dating violence victimization, perceived gravity in dating violence behaviors, sexism, romantic love myths and emotional dependence between female and male adolescents. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 11(2), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2020.02.040 (2020).

Orozco Vargas, A. E., Aguilera Reyes, U., García López, G. I. & Venebra Muñoz, A. Efectos directos e indirectos de las actitudes hacia la violencia, la desvinculación moral y las creencias normativas en la violencia escolar. UB J. Psychol. 52(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1344/ANPSIC2022.52/2.34161 (2022).

Magalhães, M. & Aparicio-García, M. E. Ambivalent sexism, mental health and partner violence among opposite-sex and same-sex couples. J. Gend-Based Violence 8(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1332/23986808Y2024D000000018 (2024).

Ariza Ruiz, A., Viejo Almanzor, C. & Ortega Ruiz, R. El amor romántico y sus mitos en Colombia: una revisión sistemática. Suma psicológ. 29(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.14349/sumapsi.2022.v29.n1.8 (2022).

Carbonell Marqués, A. & Mestre, M. V. Sexismo y mitos del amor romántico en estudiantes prosociales y antisociales. Rev. Prism. Soc. 23, 1–17 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support provided by Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR) and Universidade da Coruña.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.P.A., M.L.R.G.; Methodology: M.P.A., M.L.R.G.; Software: T.A.H.; Data Curation: T.A.H.; Investigation: M.P.A., M.L.R.G., T.A.H.; Validation: M.P.A., M.L.R.G.; Formal analysis: M.P.A., M.L.R.G., T.A.H.; Supervision, M.P.A., M.L.R.G., Funding Acquisition: M.L.R.G.; Visualization: T.A.H.; Project administration: T.A.H.; Resources: T.A.H.; Writing (original draft): M.P.A.; Writing (review & editing): M.P.A., M.L.R.G., T.A.H..

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Penado Abilleira, M., Rodicio-García, ML. & Alonso del Hierro, T. Construction and validation of the cognitive distortions in adolescents scale. Sci Rep 15, 39917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23602-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23602-x