Abstract

This study presents a hybrid seismic inversion framework to estimate 3D acoustic impedance volumes in a geologically complex and data-limited environment. The approach integrates physics-informed pseudo-well generation, based on calibrated rock physics modeling and variogram statistics, with a deep feedforward neural network (DFNN) that maps multi-attribute seismic data to acoustic impedance while substantially reducing dependence on low-frequency background models and dense well calibration. The compact DFNN serves as a high-dimensional nonlinear mapper that learns the relationship between seismic attributes and impedance logs, a task for which it is well suited, leading to accurate predictions. We generated synthetic elastic logs (compressional and shear velocities, and bulk density) using calibrated rock physics modeling and variogram-constrained stochastic simulation to supplement real well logs. We produced a lithologically diverse and statistically coherent training dataset. This process, applied to only 3 real wells, generated a robust ensemble of 36 synthetic pseudo-wells, effectively addressing the severe data scarcity and providing sufficient training data. Seismic attributes representing amplitude, phase, and frequency characteristics are selected to facilitate the model’s ability to resolve subtle geological heterogeneity. The trained DFNN is validated through a leave-one-well-out strategy yielding a cross-correlation coefficient of up to 95.4% and a normalized relative error below 1% when tested on the blind wells. Combining physical modeling with data-driven learning reduces reliance on low-frequency background models and dense calibration. Rather than replacing conventional inversion, it provides a complementary, geologically consistent, and computationally efficient approach for reliable reservoir characterization in offshore environments. Future work may focus on incorporate uncertainty quantification and volumetric convolutional networks to further improve spatial resolution and model reliability in complex subsurface settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Determining subsurface elastic properties from seismic data is paramount for successful hydrocarbon exploration, reliable reservoir characterization, and efficient field development. Acoustic impedance, in particular, offers critical insights into lithological changes, fluid distribution, and rock compaction, thus forming a cornerstone of seismic interpretation. Conventional model-based inversion methods have historically been used to derive impedance volumes. However, these methods rely heavily on well-calibration, low-frequency models, and iterative parameter tuning. Consequently, despite their widespread industrial application, the efficacy of these traditional approaches diminishes considerably in data-limited scenarios or geologically intricate settings characterized by significant lateral heterogeneity1,2,3,4.

The advent of machine learning, particularly deep learning, has catalyzed novel inversion strategies. These approaches are designed to directly learn the intricate relationships between seismic attributes and reservoir properties, circumventing the need for explicit physics-based models. Advanced deep architectures such as feedforward neural networks, convolutional neural networks, and attention-based U-Nets have shown exceptional proficiency. They effectively map complex, nonlinear patterns within seismic datasets5,6. Trained in supervised modes with well log data, these models have shown the capacity to generate high-resolution and geologically more consistent predictions, especially in their ability to integrate diverse data types and effectively manage the inherent nonlinearities of subsurface properties, thereby addressing limitations of conventional approaches7.

A significant impediment to the widespread deployment of these advanced models in practical geophysical applications stems from the inherent scarcity of labeled well data. Challenging environments such as offshore and deep carbonate reservoirs, including many fields in the Persian Gulf, often have limited well data. This scarcity makes supervised deep-learning model training prone to overfitting and spatial bias8,9. Data augmentation strategies have become progressively integrated into machine learning workflows to address this critical data scarcity. These techniques aim to increase the diversity and statistical robustness of training datasets. In geophysics, they include generating pseudo-well datasets, strategically perturbing existing logs, or synthesizing new samples based on geological and rock physics principles10.

Among the various data augmentation strategies, generating pseudo-wells through rock physics modeling stands out as a scientifically rigorous approach. This method involves meticulous modeling of the relationships between compressional velocity (VP), shear velocity (VS), and bulk density (Rho). It covers diverse lithofacies and fluid scenarios. This enables the creation of pseudo-wells that not only mimic real-world log behaviors but also explore a significantly broader spectrum of plausible subsurface conditions11,12. Pseudo-wells are not randomly generated; instead, they are constructed based on deterministic or stochastic simulations, constrained by geostatistical trends, facies distribution templates, and calibrated rock physics models. Consequently, they preserve geological plausibility and elastic realism, making them invaluable for enhancing training datasets13,14.

Integrating pseudo-wells into training datasets significantly enhances a model’s generalization capabilities, particularly evident during blind testing on wells excluded from the training phase. These augmented data help the model learn broader patterns in seismic-log relationships. This effectively reduces the impact of spatial data sparsity that could otherwise degrade performance. Furthermore, by simulating realistic variability across lithology, fluid saturation, and pore structure, the enriched log datasets empower neural networks to capture more subtle nonlinearities in seismic responses15.

The success of this data augmentation approach largely depends on how accurately the rock physics models represent real geological conditions. To ensure this, a proper rock physics workflow should be designed and tuned based on the measured data. Here, the Gassmann fluid substitution method and the differential effective medium (DEM) theory are normally utilized to compute synthetic log curves. Beyond theoretical application, parameter distributions are rigorously selected to mirror those observed in regional datasets accurately. This meticulous approach guarantees that the pseudo-wells represent field-like variability, drawing on established principles2,16.

Concurrently, the validation methodology is a critical consideration in seismic inversion, particularly with machine learning approaches. Conventional cross-validation, while common, can often lead to overly optimistic performance estimates, especially when applied to limited datasets. In this context, leave-one-well-out cross-validation emerges as a reliable alternative. This strategy systematically assesses the model’s generalizability by sequentially excluding each well from the training dataset and reserving it for independent validation. Such an approach realistically simulates real-world predictive scenarios and effectively mitigates the risk of overfitting to specific geological conditions17.

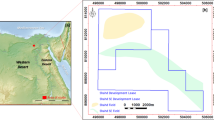

The current study is in the Aboozar oilfield, a hydrocarbon-bearing reservoir in the northern part of Persian Gulf. The geological formation under investigation spans the Ghar to the Ghar-D stratigraphic intervals. It predominantly consists of sandstone sequences with variable porosity and cementation. These characteristics make the interval particularly suitable for elastic inversion studies, as impedance contrasts within sandstone layers are more likely to reflect meaningful changes in lithology and fluid content. The prestack seismic dataset used in this study covers a 3D volume bounded by inline 54 to 612 and crossline 1600 to 1900 (21.1 km²), with a two-way traveltime (TWT) of 1000 ms. The dataset provides sufficient lateral and vertical resolutions to investigate heterogeneity within the reservoir while posing a challenge due to the limited availability of well control. We present a DFNN workflow for 3D acoustic impedance estimation. This research aims to overcome the limitations of sparse well data while maintaining geophysical realism and model interpretability in the inversion process.

Study area and stratigraphic framework

The study area is situated in the Aboozar oilfield, an offshore reservoir located in the northern sector of the Persian Gulf, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). This region lies in an important corridor of the Gulf, surrounded by several major oil fields, which enhances its relevance for regional hydrocarbon studies. Figure 1(b) presents a stratigraphic column showing the full vertical succession of formations from surface to depth. Within this column, the Ghar Formation is clearly marked, and the present study explicitly targets the interval extending from the Ghar to Ghar-D units. This interval comprises predominantly interbedded sandstone and shale deposited in deltaic to shallow marine settings and is known for its distinct elastic contrasts[18]. Nonetheless, the primary objective of this research is not stratigraphic delineation but rather the development and evaluation of a novel machine learning–driven workflow for constructing a high-resolution 3D acoustic impedance model in a data-constrained environment.

Dataset description

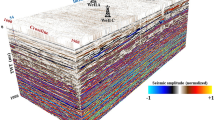

The seismic dataset consists of a 3D seismic volume resulting from prestack depth migration acquired over the Aboozar oilfield. As depicted in Fig. 2(a), the structural contour map of the Ghar Formation—interpreted from the seismic data—illustrates the reservoir geometry and the spatial distribution of the 3 wells (A, B, and C) within the seismic cube. Figure 2(b) shows the complete 3D seismic volume, covering inline 54 to 612 and crossline 1600 to 1900, with a maximum TWT of 1000 ms. This volume provides sufficient vertical and lateral resolution for detailed subsurface interpretation and reservoir modeling. All 3 wells are accompanied by detailed petrophysical logs, including VP, VS, Rho, gamma ray (GR), water saturation (Sw), total porosity (PhiT), and effective porosity (Phie). These logs cover the Ghar to Ghar-D interval, as shown in Fig. 3, providing essential data for geophysical analysis and machine learning applications in this study. These well logs form the basis for supervised machine learning and seismic-to-log integration within the acoustic impedance inversion workflow.

Methodology

To address the challenges associated with sparse well control and significant geological heterogeneity in the Aboozar oil field, this study proposes a multi-phase geophysical workflow that integrates rock physics-based data augmentation with a DFNN for estimating a high-resolution 3D acoustic impedance model. The proposed framework employs geostatistical techniques such as variogram-based spatial modeling combined with advanced machine learning to enhance the robustness and generalizability of seismic inversion. As shown in Fig. 4, the workflow begins with preprocessing of prestack seismic volumes and well log data, followed by constructing elastic rock physics models to statistically simulate and generate 36 pseudo-wells. These augmented datasets, alongside the original well logs, are used to train a DFNN optimized for nonlinear regression between seismic amplitudes and impedance values. Wavelet extraction, input normalization, and hyperparameter tuning (e.g., number of hidden layers, activation functions, and learning rate) are performed to ensure convergence and predictive accuracy. Model performance is assessed through a leave-one-well-out cross-validation strategy, particularly effective under data-constrained conditions. Further methodological details, including architectural design and implementation protocols, are described in the subsequent subsections. The DFNN was selected for its demonstrated capacity to model the complex, non-linear relationships between seismic attributes and acoustic impedance. This architecture offers an optimal balance between representational power and generalization ability, crucial for effective seismic inversion under data-constrained conditions. Its consistent performance in mapping diverse input features to continuous acoustic impedance values provides a computationally efficient and scalable solution for subsurface characterization.

Rock physics modeling and pseudo-well generation

Sparse well data coverage in the Aboozar oil field was addressed using a rock physics-driven data augmentation methodology, generating 36 synthetic pseudo-wells via an integrated workflow that combines elastic moduli estimation, lithofacies-specific petrophysical modeling, and fluid substitution11,12. This approach produces a geologically consistent ensemble of elastic logs for deep neural network training. The choice of quartz and wet clay as the end-member constituents in the rock physics modeling is firmly grounded in regional geological insights and well-established petrophysical behavior observed in the Aboozar oilfield. The target interval (Ghar to Ghar-D) primarily consists of deltaic to shallow marine sandstones, which have experienced notable diagenetic processes such as compaction and cementation. Core-based petrographic investigations and analog studies from nearby Persian Gulf fields consistently indicate a mineralogical composition dominated by detrital quartz, accompanied by clay-rich matrix and minor carbonate content. Quartz, representing a stiff elastic framework, and wet clay, modeling the more compliant matrix of shaly or altered facies, effectively span the elastic bounds of lithologies present in the interval. This two-component model is widely adopted for siliciclastic reservoirs and facilitates accurate elastic property estimation through standard rock physics averaging schemes11,12.

Furthermore, this adopted mineralogical framework aligns with regional geochemical studies, which report a predominance of silicate minerals (notably quartz and clay) and minimal carbonate content within the deltaic to shallow marine intervals of the Ghar Formation18. These mineralogical trends are corroborated by core analyses and XRD data from neighboring offshore fields in the Persian Gulf. The well log responses—particularly from gamma ray and density tools—further validate this interpretation by clearly delineating clean sandstones from shaly or diagenetically altered facies through distinct shifts in radiometric and bulk density values2,11. The quartz and wet clay mixture provides a geologically consistent and mathematically tractable basis for applying Voigt-Reuss-Hill averaging, enabling accurate estimation of effective elastic moduli while preserving essential lithological heterogeneity. The widespread use of this approach in prior rock physics studies of siliciclastic systems with limited core control reinforces its applicability to data-scarce seismic inversion settings12.

The mineral matrix was modeled as a composite of quartz and wet clay, with quartz exhibiting a higher bulk modulus and density than clay. The Voigt (KVoigt) and Reuss (KReuss) bounds for the bulk modulus, central to the Hill average19, are computed as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2):

where fq and fc are the volumetric fractions of quartz and clay, respectively, and Kq and Kc are the bulk moduli of quartz (36.6 GPa) and wet clay (20.9 GPa). The effective bulk modulus of the mineral composite (Kmineral) is then computed as the Hill average of the Voigt and Reuss bounds19, a relationship detailed in Eq. (3):

The shear modulus of the mineral composite (µmineral) is obtained similarly via the Hill average.

The dry rock frame was modeled using Hertz–Mindlin critical state theory, with parameters such as effective pressure, coordination number, and critical porosity specified in Table 1. The dry bulk (KHM) and shear (GHM) moduli are computed based on the Hertz–Mindlin theory20, as shown in Eqs. (4) and (5):

where µmineral is the mineral shear modulus (derived via Hill average), ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the mineral frame, Phic is the critical porosity, C is the coordination number, and Peff is the effective pressure. The resulting dry bulk and shear moduli were further adjusted for porosity variations using the modified Hashin–Shtrikman bounds21, ensuring mechanical consistency across the geological interval. The pore space was modeled with two fluid phases: brine and live oil. The effective fluid bulk modulus (Kfluid), which accounts for the mixture of these fluids based on Sw, was calculated using Wood’s formula22, as given in Eq. (6):

where Kbrine=2.154 GPa and Koil=0.81 GPa.

Fluid substitution was performed using Gassmann’s equation23 to compute the saturated bulk modulus (Ksat), presented in Eq. (7):

where PhiT is the total porosity, and Kdry is the dry bulk modulus of the rock frame. The saturated shear modulus was assumed to remain unchanged (Gsat=Gdry) as per standard Gassmann theory12. The saturated rock density (Rhosat) was estimated as a weighted average of the mineral and fluid densities11, computed using Eq. (8):

where Rhomineral=fq⋅Rhoq+fc⋅Rhoc is the mineral matrix density, Rhoq=2.65 g/cm3 is quartz density, Rhoc=2.35 g/cm3 is wet clay density, Rhobrine=1.0 g/cm3 is brine density, and Rhooil=0.802 g/cm3 is oil density. Finally, VP and VS wave velocities were calculated as follows12, using Eq. (9.a) and Eq. (9.b):

The calculated velocities derived key elastic attributes such as acoustic impedance, the VP/VS ratio, Poisson’s ratio, and Young’s modulus, providing a comprehensive elastic profile for each synthetic well log. The constructed rock physics model accurately captures the geological and elastic characteristics observed in real wells, thereby enabling the generation of realistic artificial wells for 3D acoustic impedance prediction across the study area. Table 1 summarizes the principal parameters utilized throughout this modeling workflow. These relationships yield the elastic log suite (VP, VS, and Rhosat) necessary for generating each pseudo-well, with the resulting synthetic logs subsequently used to train the deep neural network. By integrating mineralogical composition, pore geometry, and fluid effects, this methodology establishes a robust and geologically consistent framework for reservoir characterization and interpretation, particularly in data-limited environments. While the rock physics models provide detailed elastic parameterization, the subsequent application of statistical simulation ensures spatial continuity and facies-based realism in pseudo-well generation, bridging the gap between physical modeling and reservoir-scale prediction.

Statistical modeling and pseudo-well generation

Before statistical modeling, a seismic-to-well tie was executed to establish alignment between elastic log data and the seismic domain. Concurrently, wavelet extraction was performed to ensure accurate seismic-log integration. This preliminary step is critical for maintaining consistency between reflectivity-based modeling and subsequent inversion processes, as highlighted by recent geophysical studies emphasizing the importance of reliable wavelet estimation24,25,26. A statistical rock physics workflow was implemented to generate synthetic well logs informed by lithofacies classification and elastic modeling. Four lithofacies classes: oil-bearing clean sandstone, water-bearing clean sandstone, shaly sandstone, and tight sandstone, were defined using threshold-based conditional logic on shale volume, Phie, and Sw. This approach enabled discrete facies identification from continuous log data27. For each facies, synthetic elastic logs, specifically VP and Rho, were simulated via calibrated rock physics relationships. These synthetic logs were compared against corresponding real well logs, and residuals were analyzed to assess model accuracy. Background property trends were established and iteratively refined to enhance fidelity. Vertical variability of elastic properties was quantified through variogram analysis. A Gaussian variogram model was fitted with parameters: sample rate of 0.1524 m, maximum lag of 25 samples, sill of 1.2000, nugget of 0.4000, and vertical range of 3 samples. This ensured realistic vertical continuity and stochastic behavior in pseudo-well generation. Using the finalized variogram parameters, pseudo-wells were generated via constrained stochastic simulation, incorporating statistical distributions of key petrophysical parameters and calibrated facies trends. A total of 36 physics-constrained pseudo-wells (12 per real well A–C) were generated. The dataset, therefore, comprises two components: real measured logs (Wells A–C) and synthetic pseudo-wells. Pseudo-wells were used exclusively for training/augmentation; model selection, blind evaluation, and all reported metrics are based only on the real wells, preventing data leakage and ensuring field-relevant benchmarking. Although calibrated to the empirical distributions and facies trends of the real logs, the pseudo-wells are simulations and may not capture all local geological variability; this consideration is noted in the Discussion. For DFNN training, pseudo-wells were combined with the real logs to form input–target pairs alongside the 3D prestack seismic cube; validation used only the real wells.

The pseudo-well generation process was meticulously designed to balance geological realism with statistical variability. This multi-step workflow integrated lithofacies classification, calibrated rock physics modeling, and stochastic simulation constrained by variogram analysis. Initially, facies were labeled based on thresholded log data. Deterministic rock physics relationships, adjusted for local petrophysical trends, were then applied to assign elastic properties. Gaussian variogram models were calibrated to key properties like porosity and impedance to replicate spatial architecture and facies-dependent heterogeneity. The resulting pseudo-wells successfully capture the elastic distribution of actual wells while introducing geologically plausible heterogeneity. A rigorous quality control protocol—including residual analysis and multi-realization comparison—was implemented to ensure the synthetic datasets maintained physical consistency and geological credibility. The spatial coverage of the three real wells (A, B, and C) is confined to the central portion of the seismic cube (as depicted in Fig. 2). To supplement this area, pseudo-wells were distributed across the same region using variogram-based spatial constraints. This critical step utilized horizontal and vertical correlation ranges derived from the fitted Gaussian variogram models of the elastic properties. This systematic approach ensured that the synthetic sampling remained statistically independent while strictly maintaining the geological consistency and spatial continuity of key lithological and elastic trends across the study domain.

Data preparation for DFNN

Seismic attribute extraction was performed on the 3D prestack seismic cube along the trajectories of 3 real and 36 pseudo-wells within the Ghar to Ghar-D interval. From a comprehensive list of attributes, six were selected based on their strong statistical correlation with acoustic impedance, VP, and Rho. These include: RMS amplitude, envelope, instantaneous phase, instantaneous frequency, quadrature trace, and sweetness. This selection is consistent with recent multi-attribute ML practice, where attribute screening (e.g., PCA) and unsupervised mapping (e.g., SOM/UVQ-NN) highlight envelope, sweetness, spectral/instantaneous measures as informative predictors28,29. These attributes, chosen from amplitude, frequency, and phase domains, are widely recognized for capturing lithological contrasts, fluid effects, and impedance variability, enhancing the resolution and accuracy of inversion models30. The embedded wavelet was estimated using a statistical approach applied to a reflectivity sequence constructed from real and synthetic well logs. Assuming stationarity and minimum-phase characteristics, the extracted wavelet was validated through forward modeling by comparing synthetic seismograms with real seismic traces. Validation was performed by assessing phase alignment, spectral similarity, and time-window consistency, ensuring that the wavelet accurately represents the elastic behavior of the reservoir interval31.

An attribute selection process was implemented prior to training to avoid feature redundancy and ensure model interpretability. A correlation analysis was performed among candidate seismic attributes to identify and remove variables with high linear dependence (Pearson’s |r| > 0.9). This filtering step eliminated redundant features and improved the DFNN’s generalization ability. As a result, the final set of attributes was retained based on both statistical independence and their demonstrated sensitivity to lithological and fluid variations in previous geophysical studies. This rigorous feature selection ensured that the DFNN input space was compact, informative, and free from multicollinearity. Finally, seven high-impact seismic attributes—RMS amplitude, envelope, sweetness, instantaneous phase, instantaneous frequency, and quadrature trace—were selected based on three real wells and 36 pseudo-wells as inputs for the DFNN model to perform acoustic impedance inversion across the 3D seismic volume.

DFNN training and validation

To establish a high-fidelity nonlinear mapping between seismic attributes and acoustic impedance, a DFNN was configured with a topology optimized for sparse-data conditions. The architecture comprises 3 fully connected hidden layers, each containing 9 neurons. This configuration was empirically determined to balance representational capacity and generalization, minimizing underfitting and overfitting risks given the moderate-sized augmented dataset32,33. A Tanh activation function was applied to all hidden layers to leverage its zero-centered symmetry and facilitate faster convergence in regression contexts. A linear activation was employed at the output layer to generate continuous acoustic impedance values. To further improve generalization, L2 regularization (λ = 0.06) was introduced, penalizing large weights and suppressing over-responsiveness to high-frequency noise34. The key parameters of the DFNN are summarized in Table 2. Model optimization was carried out using the Conjugate Gradient (CG) algorithm, which employs second-order line search techniques without computing the full Hessian matrix35. Alternative optimizers, including Adam and RMSprop, were tested during preliminary trials. However, the conjugate gradient algorithm demonstrated more consistent convergence with the limited dataset and achieved slightly higher correlation on blind wells, leading to its selection for the final model. A total of 200 training iterations were conducted, ensuring convergence to a loss threshold (MSE < 10⁻⁵) without overfitting. Before training, all seismic attribute inputs were normalized to the range [–1, 1], standardizing dynamic ranges and accelerating convergence across the network. Hyperparameters, including neuron counts, iteration numbers, and regularization strength—, were initially optimized via grid-based sensitivity analysis using leave-one-well-out validation. The final configuration was chosen to achieve the best balance between accuracy and stability. The training was conducted using standard Python-based machine learning frameworks on an 8-core Intel Xeon workstation (3.6 GHz), with an average epoch duration of approximately 12.5 s.

To evaluate the mapping between seismic attributes and acoustic impedance, a correlation analysis was performed on a total of 948 data points which were extracted from our 39 wells (3 real wells and 36 pseudo-wells). For each well, 24 time-sampled points were selected at uniform intervals of 4 ms within the target reservoir window. These sample points were used to construct a scatter plot comparing predicted and reference P-impedance values. Predictions were obtained using a DFNN architecture of 3 hidden layers with 9 neurons each, trained using the selected high-impact seismic attributes. The final DFNN configuration was selected following a series of controlled comparative experiments against alternative optimization algorithms (Adam and RMSProp). The conjugate gradient optimizer demonstrated more stable convergence behavior and yielded higher predictive correlation on blind-well validation, justifying its adoption. Hyperparameters, including neuron count, learning iterations, and L2 regularization strength, were systematically tuned through grid-based sensitivity analysis within a leave-one-well-out cross-validation framework to achieve an optimal balance between predictive accuracy and generalization capability.

Results

The calibrated rock physics model produced synthetic elastic logs for VP, VS, and Rho that clearly agreed with the measured well data across the Ghar to Ghar-D interval. This strong correspondence supports the model’s applicability for simulating the reservoir’s elastic response. While this modeling and quantitative comparison were conducted for all three wells (A, B, and C), the results for Well A are presented as representative examples in Figs. 5, 6 and 7. Specifically, Fig. 5 displays cross-plots of predicted versus observed values, illustrating robust linear trends. Figure. 6 presents the distribution of differences, providing further insight into model performance. Additionally, Fig. 7 highlights the close alignment between synthetic and measured VP and Rho logs for Well A.

Distinct facies-specific elastic trends were notably evident. For instance, oil-bearing clean sandstones exhibited reduced velocities, which is attributable to fluid substitution effects. This phenomenon involves a measurable decrease in compressional and shear wave velocities resulting from the replacement of brine with hydrocarbons in the pore space, primarily due to the lower bulk and shear moduli of oil and gas compared to saline water. In contrast, shaly sandstones displayed comparatively lower elastic responses, while tight sandstones showed higher elastic responses, consistent with their respective clay content and diagenetic cementation. The quantitative quality control metrics reported in Table 3 further substantiate the overall modeling accuracy across all wells. This table provides prediction quality (PQ), correlation coefficient (CC), and normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) separately for each well. These results confirm that the rock physics model reliably captures the elastic behavior of all three wells individually, with PQ values consistently exceeding 91% and CC values above 87% for all parameters. PQ metric was computed to quantify the agreement between predicted and measured elastic log values. Defined as Eq. (10)36:

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) represents the measured value, \(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted value, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the mean of the measured values. This metric quantifies the proportion of the total variance in the measured data explained by the model, making it analogous to the coefficient of determination (R2) but expressed as a percentage for enhanced interpretability. Higher PQ values indicate superior predictive accuracy, with values exceeding 90% signifying strong model performance.

To incorporate geological heterogeneity into the inversion framework, facies classification was performed using shale volume (Vshale), Phie, and Sw derived from well logs across the Ghar to Ghar-D interval. The classification criteria used to define the lithofacies are summarized in Table 4. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the proportional distribution of the four identified facies—oil-bearing clean sandstone, water-bearing clean sandstone, shaly sandstone, and tight sandstone—within each of the three wells. These figures highlight variations in facies proportions among Wells A, B, and C, indicating lateral heterogeneity across the reservoir. Furthermore, Fig. 10 presents the depth-based facies columns for all three wells, clearly representing the vertical distribution and stratigraphic arrangement of lithofacies within the interval of interest. Collectively, these figures confirm both the lateral facies variability inferred from inter-well comparisons and the vertical heterogeneity in lithological composition, thereby supporting the development of a robust facies-based framework for subsequent variogram-constrained stochastic modeling and pseudo-well generation. To mitigate sparse well control and enhance the generalizability of the inversion model, 36 pseudo-wells were meticulously generated using the calibrated rock physics model combined with a variogram-constrained facies framework. Each pseudo-well was constructed to preserve the petrophysical trends and vertical heterogeneity observed in the original well logs, ensuring geological plausibility. As shown in Fig. 11(a), the process began by deriving calibration curves for observed and predicted Vp and Rho values. The workflow continued with aligning elastic property profiles to their corresponding background trends, as presented in Fig. 11(b). Figure 11(c) illustrates the comparison between observed and background profiles for PhiT and Matrix Stiffness Index (MSI), while Fig. 11(d) shows the residual analysis of these variables to confirm their consistency with the spatial variability observed in the original data.

Fundamental and initial stages of the sequential workflow for constructing a pseudo-well for well A across the Ghar to Ghar D interval (measured depth: 818.5–909.4 m). (a) Calibration curves derived from RPM for both observed (blue) and predicted (orange) values of VP (left) and Rho (right); (b) comparison of elastic properties (blue) with their corresponding trends (orange) for VP (left) and Rho (right); (c) comparison between observed (blue) and background (orange) trends for PhiT (left) and MSI (right); and (d) residual analysis of PhiT (left) and MSI (right) relative to their background trends.

To evaluate the consistency between the synthetic pseudo-wells and the real well data, a statistical comparison was performed based on the primary elastic properties VP and Rho. The analysis included the computation of mean, standard deviation, and variance for both datasets within the interval of interest. As summarized in Table 5, the synthetic logs show good statistical agreement with the real data, indicating that the generated pseudo-wells preserve the essential petrophysical trends. This consistency is further supported by the visual comparison shown in Fig. 11, where the synthetic curves closely follow the variations observed in the measured logs.

The final stages of the pseudo-well construction workflow are illustrated in Fig. 12. As shown in Fig. 12(a), a Gaussian variogram model was applied to the PhiT residuals to capture the vertical spatial correlation structure. Subsequently, 10 Gaussian realizations were generated for multi-property quality control, as depicted in Fig. 12(b), evaluating the consistency of synthetic logs with respect to PhiT, VP, VS, and Rho across the target interval. This multi-parameter validation step confirmed that the pseudo-wells faithfully reproduced the spatial variability and petrophysical heterogeneity observed in the original measurements, enriching the inversion training dataset with physically consistent and geologically plausible lithoelastic scenarios.

Final stages of the sequential workflow for constructing a pseudo-well for Well A across the Ghar to Ghar D interval (measured depth: 818.5–909.4 m). (a) Vertical variogram modeling of PhiT residuals using a Gaussian model; and (b) multi-property quality control by generating ten Gaussian realizations to evaluate the accuracy of the model in reproducing the variability observed within the original log data (PhiT, VS, VP, and Rho).

To visualize the quality of the generated pseudo-wells, Fig. 13 presents the VP, VS, and Rho logs for a representative example pseudo-well associated with Well A, covering the Ghar to Ghar-D interval. A total of 36 pseudo-wells were generated, with 12 pseudo-wells distributed around each of the three real wells (A, B, and C) using constrained stochastic simulation. For each pseudo-well, the (X, Y) position was randomly sampled within an elliptical neighborhood centered on the real well, with horizontal displacements limited to ± 250 m in the inline direction and ± 200 m in the crossline direction. These bounds were selected based on the spatial coverage of the seismic volume and the variogram range of the elastic property distributions to ensure sufficient statistical independence while remaining within the survey area.

The spatial distribution of the pseudo-wells around Wells B and C followed the same logic and constraints, as illustrated in Fig. 14. The elliptical placement region ensures that the training samples adequately represent local geological trends without violating spatial redundancy assumptions. It is important to note, however, that the precise surface location of the pseudo-wells is not critical. What matters is that the generated logs preserve the realistic elastic variability and petrophysical patterns required for training the DFNN. Therefore, the pseudo-wells function primarily as statistically grounded training samples, and their spatial position is constrained only to maintain independence and ensure coverage of the seismic domain.

Logs of VP, VS, and Rho for a representative pseudo-well generated around real Well A. This pseudo-well is located within a statistically valid elliptical neighborhood offset from the real well, based on the spatial constraints defined by the variogram model. The logs span the Ghar to Ghar-D interval and exhibit realistic elastic trends consistent with the lithological framework of the field.

Spatial layout of 36 pseudo-wells generated around real wells A, B, and C within elliptical neighborhoods defined by variogram-informed lateral offsets (± 250 m inline, ± 200 m crossline). The layout ensures statistical independence and full seismic coverage. While the surface locations are shown for clarity, they are illustrative only; the pseudo-wells serve as statistically and petrophysically valid training samples, and exact placement is not critical.

For input feature selection, 6 seismic attributes were retained due to their statistically significant correlations with acoustic impedance. These attributes—RMS amplitude, envelope, sweetness, instantaneous phase, instantaneous frequency, and quadrature trace—jointly capture the seismic response’s key amplitude-, phase-, and frequency-domain characteristics. Their combined utilization enhances sensitivity to lithological contrasts and fluid content variations. Prior to model training, all attribute values were normalized to the [− 1, 1] range and underwent rigorous quality control, resulting in a robust and high-fidelity input matrix for deep neural network inversion. Then, the trained DFNN model was applied to the entire prestack seismic volume, generating a 3D acoustic impedance cube for the Ghar to Ghar-D interval (Inline 54–612, Crossline 1600–1900, TWT 730–790 ms), as depicted in Fig. 15. The resulting impedance model exhibits laterally and vertically coherent patterns with a high degree of geological consistency. We observe that the low-impedance zones (blue-green) typically correspond to porous, hydrocarbon-bearing facies, whereas high-impedance regions (orange-red) represent tighter or water-saturated intervals. The cube successfully captures fine-scale stratigraphic complexity and facies transitions across the reservoir, including subtle discontinuities that are often challenging to resolve. Furthermore, integrating physics-guided pseudo-wells within this DFNN framework enables efficient reconstruction of subsurface heterogeneity with minimal real data, offering a scalable and cost-effective solution suitable for practical deployment in data-constrained or offshore fields.

Predicted 3D acoustic impedance volume generated by a DFNN, trained using seismic attributes and augmented well data. The output cube covers the range of Inline 54–612, Crossline 1600–1900, and TWT from 730 to 790 ms, and encompasses the interval of interest from Ghar to Ghar-D. The model, leveraging both real and pseudo-well logs, demonstrates spatially consistent impedance variations that reflect the geological structure across the seismic volume.

Scatter plot of predicted vs. actual P-impedance (with 1:1 reference line) based on 948 samples from 39 wells—3 real wells and 36 synthetic pseudo-wells. Markers are coded by data origin: real wells (A, B, C) are listed explicitly in the legend, while pseudo-wells follow the labels Pseudo.W.[A/B/C] _01_sim_XXXX (12 per real well; 36 total). Pseudo-wells were used for training/augmentation only; reported validation statistics are computed on real wells. Predictions were obtained with a DFNN (three hidden layers of nine nodes each) trained on seven seismic attributes, yielding a cross-correlation of 95.4% and an RMSE of 0.592.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the inversion workflow, a visual comparison is provided in Fig. 17 between the pre-inversion normalized seismic amplitude and the post-inversion acoustic impedance section along inline 148 to 610 at crossline 1600. The results show improved stratigraphic continuity and more precise delineation of subsurface heterogeneity, supporting the model’s ability to extract geologically consistent impedance structures from seismic data. The DFNN-predicted impedance section also reveals a distinct low-impedance anomaly, further validating the model’s predictive performance and confirming its ability to capture subtle lithological variations. This anomaly appears as a localized yellow–green zone within the study interval, corresponding to a low-impedance layer that aligns with the expected lithological contrast of the target sequence.

(a) Normalized seismic amplitude section (pre-inversion) along inline 148 to 610 at crossline 1600, highlighting the study interval from Ghar to Ghar_D. (b) Corresponding P-wave acoustic impedance volume (post-inversion) predicted by the trained DFNN. Compared to the raw seismic data, the inversion output exhibits enhanced stratigraphic resolution, improved vertical continuity, and clearer delineation of subsurface heterogeneities. The main low-impedance anomaly within the target interval is clearly indicated, corresponding to the interval of interest.

Furthermore, we validated our model using a leave-one-well-out cross-validation strategy based on the 948 test points sampled from the three real wells and their associated pseudo-wells. As shown in Fig. 16, the cross-plot of predicted versus actual acoustic impedance values demonstrates a strong linear relationship, with a cross-correlation coefficient of 0.954 (95.4%) and an RMSE of 0.592. When normalized against the average impedance (~ 8000 (m/s)·(g/cm³)), this corresponds to a relative error below 1%, indicating high prediction accuracy. Our results show consistent performance across different lithofacies and impedance ranges with no apparent systematic bias. The close alignment of points along the 1:1 line—across real and pseudo-wells—confirms the DFNN’s ability to generalize beyond the training data and accurately capture nonlinear relationships between seismic attributes and impedance, even in areas with limited well control. The integration of rock physics-based trends into the pseudo-wells significantly enhances geological interpretability. This solid foundation—built upon calibrated rock physics, statistical data augmentation, and supervised learning—supports a more confident, data-driven understanding of reservoir complexity. The broader implications of these findings are elaborated in the following sections.

Discussion

This study shows how integrating physics-guided pseudo-well generation with a DFNN can improve acoustic impedance inversion even in areas challenged by limited well data and/or complex geology. This integrative framework represents a crucial departure from conventional model-based inversions, which rely heavily on dense low-frequency calibration. Instead, our approach leverages a meticulously calibrated rock physics model to produce synthetic pseudo-wells that faithfully reproduce realistic petrophysical and elastic trends. As visually demonstrated in Figs. 5, 6 and 7 and quantitatively supported by Table 3, this rock physics modeling successfully generated synthetic elastic logs (VP, VS, and Rho) exhibiting strong alignment with measured well data, thereby validating the accuracy and geological plausibility of the augmented dataset.

A key strength of this methodology lies in its stochastic pseudo-well generation, strictly constrained by vertical variogram models and facies-guided petrophysical trends (Fig. 12). This strategy significantly broadens the diversity of lithofacies and elastic property combinations used to train the inversion network. As illustrated in Fig. 12, the generated pseudo-wells effectively populate the elastic parameter space, mitigating the typical limitations associated with sparse well control—particularly in offshore or frontier environments. Additionally, the seismic attributes selected for training—designed to capture amplitude, phase, and frequency-domain characteristics—collectively enhance the model’s sensitivity to geological heterogeneity and fluid-related variations, resulting in a more detailed and geologically realistic subsurface reconstruction.

This integrated workflow demonstrates a notable advancement compared to recent machine learning-based seismic inversion techniques. While Zheng et al. (2022) effectively showcased the efficacy of synthetic data for enhancing inversion accuracy7, their methodology notably lacked the multi-layered geological realism that our approach achieves through the rigorous incorporation of rock physics and variogram constraints. Similarly, Bai et al. (2025) leveraged synthetic rock images for data augmentation; however, their validation was confined to idealized scenarios, which limited their practical generalizability due to an absence of field-scale geological calibration10. Furthermore, although El-Sayed et al. (2025) highlighted the benefits of physics-informed learning for reservoir characterization, their specific workflow was validated solely on post-stack inversion within a simplified geological setting4. In distinct contrast, this study rigorously applies a novel physics-based pseudo-well generation and DFNN workflow directly to a genuine 3D prestack seismic dataset, thereby achieving remarkably robust impedance prediction within highly complex stratigraphic environments, achieving cross-correlation coefficients up to 95.4% and relative prediction error below 1% (Fig. 16). The achieved results generally exceed standard performance benchmarks reported in studies. From a practical perspective, this workflow provides a scalable and economically efficient solution for subsurface characterization, which is especially valuable in areas with limited well infrastructure. The generated acoustic impedance volume (Fig. 15) captures vertical and lateral geological continuity, allowing for the precise resolution of crucial features like thin shale interbeds, compartmentalized sand bodies, and subtle gradational facies boundaries. The model’s inherent spatial consistency and high interpretability underscore its utility for adequate reservoir delineation, dependable facies classification, and strategic well planning. Importantly, the method’s ability to achieve accurate stratigraphic representation without overfitting to scarce control data makes it exceptionally beneficial for applications in the offshore field, where traditional approaches frequently fall short.

A broader examination of recent seismic inversion studies reveals a prevailing emphasis on synthetic validation, with limited attention to real-world generalizability. As summarized in Table 6, several efforts—including37,38—demonstrated promising results using synthetic models. Yet their applicability to field data remains uncertain due to the absence of blind well validation. Similarly, although39,40 introduced innovative physics-informed networks, their evaluation focused predominantly on geological consistency without reporting numerical metrics. In contrast, our study bridges this gap by combining quantitative accuracy with geological plausibility, validated through blind field data. This dual validation approach ensures statistical robustness—reflected by cross-correlation values exceeding 0.95 and relative prediction errors below 1%—and preserves interpretability and geologic continuity, making the method well-suited for practical subsurface applications.

It is important to acknowledge several methodological considerations inherent to this framework. The core reliability of the pseudo-well generation process is fundamentally tied to the accuracy of the underlying rock physics modeling, the geostatistical fidelity of the facies templates, and their corresponding petrophysical distributions. Potential inaccuracies in mineralogical assumptions or fluid saturation models could propagate systemic biases through the entire inversion workflow. While the variogram-based multi-realization validation (Fig. 12b) indeed confirms the Gaussian models’ capacity to replicate key petrophysical patterns (PhiT, VP, VS, and Rho) from real log data, it does not comprehensively account for the full spectrum of inherent modeling uncertainty. Crucially, the absence of explicit uncertainty quantification—covering aleatoric (data-driven) and epistemic (model-based) components—represents a clear direction for future enhancement. Furthermore, while the DFNN exhibits strong generalization capabilities for blind wells within similar stratigraphic and structural contexts, its predictive performance may decline when extrapolated to geologically dissimilar settings beyond the established lithofacies space. Although only three real wells were available, constituting the entire field dataset, which may limit calibration and introduce bias, to mitigate overfitting under these constraints, we employed a simple DFNN with three hidden layers and L2 regularization, combined with strict leave-one-well-out validation to prevent data leakage. Although relatively shallow, this architecture balanced predictive accuracy and overfitting risk given the severe data limitations. More complex models, such as convolutional or recurrent neural networks, can better capture spatial seismic patterns but generally require larger, denser training datasets. Future work will explore volumetric CNN or hybrid architectures to improve spatial resolution and robustness as more data becomes available. The normalized error falls below 1%, which may seem unusually low; however, this result is based on a strict leave-one-well-out validation protocol, where each well was fully excluded from training and used only for blind testing. Pseudo-wells were used solely for training augmentation and not in validation, helping to prevent data leakage. Along with L2 regularization, this approach aimed to reduce overfitting. Still, some degree of overfitting cannot be entirely ruled out, and future work will include uncertainty quantification to further improve reliability.

To address the remaining methodological limitations, future research should prioritize incorporating formal uncertainty quantification frameworks capable of handling both aleatoric and epistemic components in data-sparse inversion workflows. Techniques such as Monte Carlo dropout and variational inference—which approximate Bayesian inference within deep neural networks—offer promising avenues for estimating predictive distributions and model confidence. Furthermore, integrating deterministic seismic inversion with the statistical outputs from the DFNN could facilitate hybrid workflows that seamlessly combine physical rigor with machine-learned flexibility. Regarding architectural advancements, adopting 3D convolutional networks or encoder-decoder frameworks like U-Net may better exploit spatial continuity within volumetric seismic data, thereby enhancing the resolution of subtle stratigraphic features. Incorporating physics-informed loss functions or embedding prior geological knowledge—such as facies transition rules or petrophysical constraints—into the training regime could further improve generalization, especially when extending the model to new fields or stratigraphic intervals with limited well control. Lastly, developing multi-resolution strategies that couple high-resolution impedance prediction in well-calibrated zones with coarser approximations in poorly sampled regions could enhance computational efficiency without sacrificing geological realism.

In terms of computational trade-offs, the pseudo-well generation phase—including rock physics modeling, lithofacies classification, and variogram-constrained stochastic simulation—required approximately 3 h for the full set of 36 wells. The subsequent DFNN training, using a conjugate gradient optimizer with early stopping, was completed in under 20 min on a standard workstation (Intel i7 CPU, 32 GB RAM). Compared to traditional model-based inversion methods that often require several hours per run due to iterative forward modeling and regularization, the proposed workflow offers a substantially reduced computational burden. While the initial physics-based modeling introduces some overhead, the overall framework remains efficient and scalable for field-scale applications. Moreover, access to preliminary field data and geological context can further streamline model selection, reduce the setup time for rock physics modeling, and accelerate pseudo-well generation in future applications.

Ultimately, this research illustrates that embedding geological constraints within data-driven inversion workflows can effectively facilitate the estimation of 3D acoustic impedance volumes in settings with sparse data. Although this approach might not always surpass the accuracy of traditional model-based inversions, it undeniably provides a viable alternative that curtails computational and interpretive efforts. The method delivers a geologically plausible impedance model by strategically integrating calibrated rock physics and stochastic pseudo-well augmentation. This model offers strong support for preliminary subsurface interpretation, making it a valuable asset for offshore or frontier regions characterized by sparse well control. The broader methodological and practical implications of this work will be further examined in the concluding section.

Conclusions

This research introduces a hybrid inversion framework that combines physics-informed pseudo-well generation with a DFNN model to estimate 3D acoustic impedance volumes using limited well data. The methodology leverages a calibrated rock physics model and variogram-constrained stochastic simulation to produce synthetic elastic logs (VP, VS, and Rho), which exhibit close alignment with observed well measurements, supporting the plausibility of the augmented dataset. Seismic attributes selected for training—chosen to reflect amplitude, phase, and frequency information—enabled the network to capture key geological patterns. The model showed capability in representing structurally relevant features, including thin shale interbeds and compartmentalized sand bodies, with reasonable spatial accuracy and continuity. Rather than aiming for exact replication, the workflow emphasizes geological coherence and interpretive consistency, making it particularly suitable for data-constrained environments.

Evaluation of the inversion performance utilized a leave-one-well-out validation strategy, yielding cross-correlation coefficients as high as 95.4% and normalized relative errors under 1%. Our results indicate a strong predictive accuracy, which favorably compares with previously reported benchmarks. Furthermore, the generated acoustic impedance volume reveals consistent vertical and lateral continuity, aligning well with known stratigraphic features and thereby showcasing its utility for facies interpretation and reservoir monitoring in data-limited environments.

The innovative aspect of this work lies in the unified framework that merges physics-based rock-physics simulation with data-driven inversion. This hybrid approach enhances geological realism and predictive reliability compared to conventional or purely data-driven methods. The proposed framework presents an effective and scalable alternative to conventional model-based inversion by reducing dependence on low-frequency background models and extensive well calibration. While it is not intended to replace all traditional methods, it provides a dependable solution for generating geologically coherent impedance volumes in data-scarce environments—a particularly valuable advantage in offshore fields with sparse well coverage and significant subsurface heterogeneity.

The future progression of this approach could be significantly strengthened by incorporating formal uncertainty quantification techniques—such as Bayesian inference or deep ensemble methods—to better characterize aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties inherent in data-scarce inversion workflows. In parallel, adopting 3D convolutional neural architectures may enhance the model’s ability to resolve subtle geological features by leveraging volumetric spatial context. Together, these advancements would reinforce the framework’s scalability, computational efficiency, and geological consistency, offering an effective foundation for data-driven subsurface interpretation in complex and underexplored geological settings.

Data availability

The raw data used in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements and proprietary restrictions with the data provider. Interested researchers may contact Arash Ghiasvand (first author).

References

Zhao, L., Nasser, M. & h. Han, D. Quantitative geophysical pore-type characterization and its geological implication in carbonate reservoirs. Geophys. Prospect. 61, 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2478.12043 (2013).

Dvorkin, J., Gutierrez, M. A. & Grana, D. Seismic Reflections of Rock Properties (Cambridge University Press, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511843655

Russell, B. H., Hedlin, K. J. & N1-N14. Extended poroelastic impedance. Geophysics 84. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2018-0311.1 (2019).

El-Sayed, A. S., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. M. Pre-stack seismic inversion for reservoir characterization in pleistocene to pliocene channels, Baltim gas field, Nile Delta, Egypt. Sci. Rep. 15, 1180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75015-x (2024).

Moseley, B., Markham, A. & Nissen-Meyer, T. Fast approximate simulation of seismic waves with deep learning. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:1807 06873. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.06873 (2018).

Tao, L., Ren, H. & Gu, Z. Acoustic impedance inversion from seismic imaging profiles using self-attention U-Net. Remote Sens. 15, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15040891 (2023).

Zheng, X., Wu, B., Zhu, X. & Zhu, X. Multi-task deep learning seismic impedance inversion optimization based on homoscedastic uncertainty. Appl. Sci. 12, 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031200 (2022).

Mosser, L., Dubrule, O. & Blunt, M. J. Stochastic seismic waveform inversion using generative adversarial networks as a geological prior. Math. Geosci. 52, 53–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11004-019-09832-6 (2020).

Dramsch, J. S., Corte, G., Amini, H., Lüthje, M. & MacBeth, C. Second EAGE Workshop Practical Reservoir Monitoring 2019. 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2019). https://doi.org/10.3997/2214-4609.201900028

Bai, K., Zhang, Z., Jin, S. & Dai, S. Rock image classification based on improved EfficientNet. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03706-0 (2025).

Avseth, P., Mukerji, T. & Mavko, G. Quantitative Seismic Interpretation: Applying Rock Physics Tools to Reduce Interpretation Risk (Cambridge University Press, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511600074

Mavko, G., Mukerji, T. & Dvorkin, J. The Rock Physics Handbook (Cambridge University Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108333016

Connolly, P. A. & Hughes, M. J. Stochastic inversion by matching to large numbers of pseudo-wells. Geophysics 81. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2015-0348.1 (2016). M7-M22.

Li, J. et al. A lithofacies prediction method based on stochastic simulation. J. Geophys. Eng. 20, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/jge/gxad003 (2023).

Wang, J., Cao, J., You, J., Cheng, M. & Zhou, P. A method for well log data generation based on a spatio-temporal neural network. J. Geophys. Eng. 18, 700–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/jge/gxab046 (2021).

Xu, S. & Payne, M. A. Modeling elastic properties in carbonate rocks. Lead. Edge. 28, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3064148 (2009).

Iturrarán-Viveros, U., Muñoz-García, A. M., Castillo-Reyes, O. & Shukla, K. Machine learning as a seismic prior velocity model Building method for full-waveform inversion: A case study from Colombia. Pure Appl. Geophys. 178, 423–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-021-02655-9 (2021).

Carcione, J. M. et al. Rock acoustics of diagenesis and cementation. Pure Appl. Geophys. 179, 1919–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-022-03016-w (2022).

Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A. 65, 349. https://doi.org/10.1088/0370-1298/65/5/307 (1952).

Dvorkin, J. & Nur, A. Elasticity of high-porosity sandstones: theory for two North Sea data sets. Geophysics 61, 1363–1370. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1444059 (1996).

Hashin, Z. & Shtrikman, S. A variational approach to the theory of the elastic behaviour of multiphase materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 11, 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(63)90060-7 (1963).

Wood, A. A. Textbook of Sound 3rd Ed. (G. Bell & Sons, 1955).

Gassmann, F. Uber die elastizitat Poroser medien. Vierteljahrsschrift Der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Zurich. 96, 1–23 (1951).

Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic data analysis: Processing, inversion, and interpretation of seismic data. Society Explor. Geophysicists. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.9781560801580.fm (2001).

Edgar, J. A., Van der Baan, M. & V59-V68. How reliable is statistical wavelet estimation? Geophysics 76 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3587220

Ma, L., Han, L. & Feng, Q. Deep learning for high-resolution seismic imaging. Sci. Rep. 14, 10319. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61251-8 (2024).

Grana, D. & Della Rossa, E. Probabilistic petrophysical-properties estimation integrating statistical rock physics with seismic inversion. Geophysics 75, O21–O37. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3386676 (2010).

Ismail, A., Radwan, A. A., Leila, M., Abdelmaksoud, A. & Ali, M. Unsupervised machine learning and multi-seismic attributes for fault and fracture network interpretation in the Kerry Field, Taranaki Basin, New Zealand. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9 (122). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-023-00646-9 (2023).

El-Dabaa, S. A., Metwalli, F. I., Maher, A. & Ismail, A. Unsupervised machine learning-based multi-attributes analysis for enhancing gas channel detection and facies classification in the Serpent field, offshore Nile Delta, Egypt. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour.. 10, 185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00907-1 (2024).

Chopra, S. & Marfurt, K. J. Seismic Attributes for Prospect Identification and Reservoir Characterization. (Society of Exploration Geophysicists and European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1190/1.9781560801900

Walden, A. & Hosken, J. An investigation of the spectral properties of primary reflection coefficients. Geophys. Prospect. 33, 400–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2478.1985.tb00443.x (1985).

Géron, A. Hands-on Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems (O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2022).

Chen, H., Gao, J., Zhang, W. & Yang, P. Seismic acoustic impedance inversion via optimization-inspired semisupervised deep learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2021.3107257 (2021).

Goodfellow, I. Deep Learning. (MIT Press, (2016). https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2016.22.4.351

Shewchuk, J. R. An Introduction to the Conjugate Gradient Method Without the Agonizing Pain (Carnegie Mellon University, Department of Computer Science, 1994).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R. Vol. 103 (Springer, 2013).

Das, V., Pollack, A., Wollner, U. & Mukerji, T. Convolutional neural network for seismic impedance inversion. Geophysics 84, R869–R880. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2018-0838.1 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Frequency-dependent AVO analysis: A potential seismic attribute for thin-bed identification. Geophysics 86. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2020-0777.1 (2021).

Sotelo, V., Almanza, O. & Montes, L. Post-stack seismic inversion through probabilistic neural networks and deep forward neural networks. Earth Sci. Inf. 17, 1957–1966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-024-01251-4 (2024).

Miele, R., Levy, S., Linde, N., Soares, A. & Azevedo, L. Deep generative networks for multivariate fullstack seismic data inversion using inverse autoregressive flows. Comput. Geosci. 188, 105622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2024.105622 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arash Ghiasvand: Methodology, conceptualization, data curation, software, writing original draft, review and editing.Abdolrahim Javaherian: Supervision, methodology, visualization, validation, review and editing. Maryam Amirmazlaghani: Supervision mMethodology, validation, review and editing.Mohammad Reza Saberi: Methodology, software, visualization, validation, review and editing. Hadi Mahdavi Basir: Methodology, validation, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghiasvand, A., Javaherian, A., Amirmazlaghani, M. et al. A physics-informed deep learning approach for 3D acoustic impedance estimation from seismic data: application to an offshore field in the Southwest Iran. Sci Rep 15, 39879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23611-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23611-w