Abstract

As a novel study, a newly formulated electroless biocide amphiphilic coating protected brass alloy in artificial seawater contaminated with bacteria. A new galvanic cell is represented for electroless deposition. The adherent polymeric complex of formula [Sn(tetra dentate ligand cephradine)Cl] was deposited. Synergism of tin and cephradine in the coating improved the antibacterial activity, as shown by a lower MIC than native cephradine antibiotic. The insulating, adherent coating surface film protected the brass alloy against microbiologically induced corrosion and showed no biofilm formation, as the compatible coating constituents kill and stop bacterial growth. The delocalized electron (s) permeated lipid layers and penetrated the microbial cell membrane, forming hydrogen bonds with active centers on the constituents of bacterial cells, perturbing respiration and killing bacteria. Polymerization decreased the polarity of the tin coating, increasing its lipophilicity and enhancing penetration. The electrochemical parameters (increased charge transfer resistance (Rct), reduced capacitance of the electrical double layer (Qdl) indicated a capacitive insulating coating. The low limiting dissolution current (156 mA cm−2 for 0.00013 M organotin, compared to 250 mA cm−2 for the blank sample) confirmed the inhibition of microbial corrosion by the organotin coating. However, the predominant form of corrosion is pitting corrosion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copper (Cu) is a relatively low-cost metal that is efficiently worked, ductile, and malleable (drawn into excellent electrical conducting wires due to good mechanical workability1; it is used in the manufacturing of heat exchangers and cooling systems. Cu piping or brass equipment (although durable may damage an entire batch of soap because copper salts accelerate soap’s rancidity. Cu is a common impurity or tramp element in most steels, promoting hot shortness, increasing strength and hardness through heat treatment, aging, and improving corrosion resistance2. Cu is an anti-fouling agent used widely inshore and offshore in the marine environment (e.g., heat exchanger tubes in desalination and power generation plants)3. Cupro-Ni alloys in atomic weight percentage 90/10, 70/30 are used in marine piping3. Monel alloy 400 (65% Ni, 30% Cu resists HCl and is used in processes involving chlorinated solvents and HCl formation in the alkaline and neutral salts encountered in the distillation and high velocity seawater4.

Brass (copper-Zn) is an advantageous copper alloy. Zn alloying element increased the mechanical strength and gave it a golden yellow. The atomic ratio content varied (10%–45% Zn) with the addition of other alloying elements to achieve synergistic combined properties, such as machinability, strength, hardness, ductility during both hot and cold working, conductivity, and corrosion resistance5. Many other alloying elements, including those that created the most complicated Cu alloys, were used. These alloys include the α phase (with up to 31% Zn in binary alloys, 1% Sn (admiralty brass), and 2% Al-brass), as well as 1–2% Pb, which improved machining.

Small Pb segregates: improved ductility on cold working by controlling metallurgy, physicochemical, and electrochemical behavior post machining, made brass standard for water fittings (long lasting in closed circuits such as central heating systems and fresh water supplies of drinking water. In certain known regions, the aggressive water supply requires cast gunmetal alloys, such as CZ132 (CuZn36Pb2As), which are resistant to dezincification. It is used for service above ground and is mandatory for underground applications6. The alloying elements Mn, Fe, Al, Si, Sn, and As improved strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance7.

Duplex α-β brass contains above 31% Zn, 1% Sn (naval brass), or 1–3% Pb to assist machining. Pb or Pb-free α and α-β brass are used in the cast and the wrought form. High-tensile α-β brass or β alloys contain up to 5% Al and 1–2% one/ more Sn, Pb, Fe, Mn elements used in both wrought and cast form7. Brass is the primary construction alloy for the shell and tube of heat exchangers in cooling water systems, used to extract steam from both turbines and other sources. It is the most applied Cu alloy in distillers, valves, water pipelines, storage tanks, heat exchangers, pumps, and condensers due to its good thermal and electrical conductivity, as well as excellent corrosion resistance7.

Brass corrodes in aerated neutral electrolytes. Nitric acid pickling causes general uniform corrosion (decreases thickness and service life). Cu oxidized into cuprite adherent surface layer film (oxygen reduced at the exterior). Further oxidation resulted in the accumulation of cupric precipitates in the overlying pores. Deczincified, spongy, fragile, and porous Cu regions resemble native brass. Brass may be completely dissolved, then Cu(II) ions are deposited. In α-brass, the whole Cu surface corroded in the affected areas. Uniform layer dezincification perforation occurs more slowly than the frequently occurring localized plug type8.

In α-β brass, the Zn-rich β phase preferentially attacked and dissolved. Zn-corrosion products are swept away or deposited on the Cu surface. Dezincification occurs in stagnant acid chloride solutions and at high temperatures. The concentration of Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions increased in the solution. Cu(II) redeposited on the Cu surface forms a porous structure, allowing corrosive species to penetrate the metal surface and subsequently cause dezincification. Further dezincification occurs by volume diffusion of Zn to the brass/solution interface. Dezincification can occur in two types: uniform layer type or localized plug type. It typically occurs in high brass (high Zn content) in acidic media, or in low brasses (low Zn content) in neutral, alkaline, or slightly acidic media8.

The reported corrosion inhibitors (CIs) for brass included eco-friendly natural products, thiadiazoles, mercapto-benzimidazoles, phosphonates, amino acid derivatives, and chitosan biopolymers1. Several CI adsorbed at Cu/solution interface: azoles, triazoles in alkaline and neutral media, 4-NH2-1,2,4-triazole/HCl, 2-SH-1-CH3-imidazole/H2SO4 (inhibition efficiency (IE) 81% at 0.0001 M), benzotriazole inhbitis pitting corrosion: wt.% 2-benzimidazolethiol and sulfathiazole in di-Cl-acetic acid (IE: 80%, 77% repectively); In aerated 0.5 M H2SO4 (indole-3-RCOOH at different temperatures, N-(5, 6-di-ph-4,5-di-H-1–2-4]triazin-3-yl)-guanidine, Ph-azo-pyrazolones or OH-quinoline and Br-PhCH2COO-1–2-3-triazole, pyrazoles in 0.1 M, 0.5 M HCl. In addition to (2-Cl/F-aniline, 2-NH2-phenetole, 2-ethylaniline, o-NH2-anisole, N-ph-1,4-phenylenediamine hexadecyl pyridinium-Br and hexa-decyl-tri-CH3-NH4Br, 3-NH2-1, 2, 4-triazole-5-thiol/0.5 M and o-toluidine9.

Another reported CI included bis- (1,1-benzotriazolylmethylene)-(2,5-thiadiazolyl)-disulfide in 3% NaCl and 0.5 M HCl. In addition to: 2-({-1-CH3-3-[(2 sulfanyl-Ph-NH]butylidene}-amino)-1-benzenethiol,2-({-1,2-di-Ph-2-[(2-sulfanyl-Ph)-NH]-ethylidene}-NH2)-1-benzenethiol,5-(3-NH2-Ph)-tetrazole in HCl. CI for dezincification was benzotriazole in 0.1N (HCl, H2SO4, NH4C1. Thiourea, thioglycolic acid, thioglycol, and halo-acetic acid in acidic chloride and sulphate solutions, tetrazole derivatives/HNO3, benzotriazole/NaCl, LiBr, HCl, 0.5 M NaCl. 2-CH3-benzimidazole/NaCl, Ph-hydrazone for pitting in 2.0 M HCl, Polyethylene glycol, imidazole, azoles, and gelatin biosurfactant in H2SO410.

Microbiologically induced corrosion (MIC) of metals and alloys caused by the presence of microorganisms (aerobic bacteria, anaerobic sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB), fungi) and/or surface biofilms. This problem causes trillions of dollars in annual losses for monitoring and control. Microorganisms initiate MIC by modifying the localized environment at the metal/solution interface or by initiating a pitting attack under an adherent biofilm. MIC damages many metals and alloys in marine environments, as well as cooling water systems (made from mild steel and brass alloy), power generation, and pipelines in the oil and gas industry11. The common corrosive bacteria are Bacillus cereus EN14, Achromobacter xylosoxidans EN15, and A. xylosoxidans EN16. The aerobic and SRB bacteria are isolated from different sources. MIC controlled by using biocides and nanocomposites containing nanoparticles with a large surface area improved interaction with bacterial cells. Montmorillonite loaded with an antibacterial agent. Schiff bases heterocyclic organic compounds were also used as biocides11. The terms “biofilm” and “biofouling” are related concepts but refer to different phenomena: The biofilm is a structured community of microorganisms, such as bacteria, algae, and fungi, that adhere to natural and artificial surfaces, often embedded in a self-produced polymeric matrix. Biofilms have a complex architecture that protects microorganisms against environmental stress, antimicrobial treatments, and the immune response. Biofouling is the unwanted accumulation of biological material (including biofilms) on surfaces submerged in, or exposed to, water. Biofouling is a significant issue in aquatic and marine environments, impacting various structures, including ship hulls, underwater pipelines, and cooling systems. The presence of biofouling causes problems, including increased drag on vessels, corrosion, and reduced efficiency in heat exchangers. Biofouling encompasses not only the initial formation of biofilms but also the subsequent growth of larger organisms, such as barnacles and mussels11.

Biofilm formation by bacterial microorganisms (MOs) causes (MIC), represented in supplementary information (SI), Fig. SI.1. Various mechanisms and MOs damage brass in marine environments by corrosive chemicals and aggressive H2S from the reduction of sulphate ions by SRB. Aerated wastewater contains nutrients for bacteria (modified M/solution interface causing pitting corrosion). Biofouling decreased the performance of the heat exchangers due to the hindrance of heat transfer11.

The corrosion of brass alloy in aggressive saline natural wastewater containing bacterial nutrients (dissolved oxygen, pH, heavy metals, organic matter, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)) has rarely been studied. Cephradine is an antibiotic (Ab) active against many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including penicillinase-producing Staphylococci12. This Ab has not yet been reported as a corrosion inhibitor for brass. This study aims to control the MIC of brass by low-cost organotin coating to minimize the use of toxic, dangerous chemical biocides (oxidizing, non-oxidizing, and methylene bis-SCN) that are efficient but negatively impact the environment. This study further aims to evaluate this novel polymeric coating for brass in the artificial marine wastewater (as an alternative, safer coating than toxic tributyl(C4H9)3Sn (TBT) compounds, which are potent biocides encountered in anti-fouling marine paints).

Materials and methods

The materials

All materials and chemicals used in this study were of analytical purity and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. The active chemical ingredient, cephradine, is obtained from local manufacturers and suppliers, including International Pharmaceutical Industries Co., Egypt (IPICO). The anhydrous stannous tin(II) chloride (SnCl2) is a colorless orthorhombic crystal, m.p. 246 °C, purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. Brass sheets were obtained from Copper Co.-Alexandria-Egypt. The elemental chemical analysis of brass in atomic wt.% was Ca (0.9), Sn (0.2), Mo(0.1), Fe(0.8), Zn (31.4), Cu(66.6).

Coating formulation and application

In electroless plating, tin is deposited by the chemical reduction of Sn(II) ions using a suitable reducing agent, such as Sodium Hydrogen Phosphate (NaH2PO2), which is nontoxic, stable, eco-friendly, and readily available in bulk quantities. The deposition conditions consist of only the electrolyte composition and temperature. The composition of the electrolyte bath (SnCl2, 20 g/L; NaH2PO2, 20 g/L; sodium acetate, 10 g/L; sodium succinate, 15 g/L) is heated to a temperature of 93 °C. The electroless mechanism represented by Eqs. (1), (2) and (3)13,14:

All solutions, precursors, tin chloride, and cephradine additive involved in the electrolyte bath mixed (water–methanol) were colorless. However, the yellow color of organotin formed as a colloidal polymer suspension, as shown in Fig. 1.

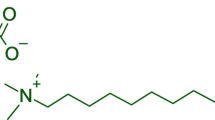

Since copper is more noble than hydrogen in the EMF series, the produced proton from the cell reaction is noncorrosive to copper but could affect zinc alloying elements9,10. For this reason, the coating is first prepared and then applied to the brass surface by hot dipping. The primary coating constituent and the polymeric structure of the Sn complex are represented in Fig. 2.

The general formula of Sn polymer composite coating is suggested based on the coordination of cephradine ligand to the central Sn(II)ion via amide, lactam carbonyl, COO−, and N-azo-moieties. N-heteroatoms donate free lone pairs to Cu, forming a coordinate-type bond. The N-atom of the β-lactam thiazolidine ring and the COO− ion formed a 5-membered ring. Sn complex is non-toxic, insoluble in water and common organic solvents. Coordination of cephradine to Sn(II) ion could enhance the antibacterial activity and protect brass alloy15. Organo Sn coating deposited on the brass surface as a thin film protective layer.

Characterization of coating

The polymeric structure of organo-tin coating was confirmed from the measured inherent viscosities (ηinh) for 0.5 g/dL concentration. A weight 0.001 g sample coating dissolved in 250 mL DMSO. The sample viscosity was determined at 30 °C using a Ubbelohde viscometer and Eqs. (4), (5) and (6).

where ηo and η are the viscosities of pure solvent and polymer solution, respectively.

The value ηinh equals 0.4 dLg−1 indicated a moderate molecular weight polymeric coating matrix16.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the coating sample were recorded using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrophotometer, covering a frequency range of 400–5000 cm−1. The powder X-ray diffraction pattern is collected over a 2θ range of 5° to 80° with a Cu-Kα x-ray (λ = 1.54 Å) radiation source.

Triplicate measurements of the antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the test organisms were performed at sample concentrations ranging from 100 to 0.007 µg/mL. The organotin coating was added to the nutrient broth, diluted with a loopful of the test organism to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard, and introduced into tubes containing broth media seeded with the test organisms (control). Cultures are incubated at 25 °C.

The artificial waste seawater containing colonized bacteria microorganisms (MOs) was isolated and obtained from the Institute of Graduate Studies and Research, Microbiology Department, Alexandria University, Egypt. The samples of the SRB mixed culture were isolated from wastewater from Alexandria Petroleum Co. The culturing media was Postgate B (g/L): 0.5 KH2PO4, 1.0 NH4Cl, 1.0 Na2SO4, 0.1 CaCl2.6H2O, 2.0 MgSO4.7H2O, 5 mL (60–70%) sodium lactate, 1.0 mL yeast extract, 0.1 mL ascorbic acid, 0.1 mL Thioglycollic acid, 0.5 FeSO4.7H2O, 26 NaCl, 500 mL seawater, and 500 mL distilled water. SRB was isolated by transferring 1 mL of each sample into a screw capped Falcon (15 mL) containing Postgate B media for culturing (SRB). The wastewater was first diluted with distilled water. The falcon tube is then placed inside an anaerobic jar and incubated for 7 days at 35 °C. Black turbidity indicated the growth of (SRB). Postgate B medium, with the same chemical composition, was used with the addition of agar to form a solid medium. One mL was diluted using several dilutions and plated to determine the viable count. The plates were incubated at 30 °C in a glass jar with an anaerobic bag and 1 g of pyrogallol to create anaerobic conditions and then incubated at 35 °C for 7 days. The SRB colonies were stained with Gram stain and examined under a light microscope at a magnification of 50x. The isolated bacterial strain is identified as a sulfate-reducing bacterium (SRB). The growth of SRB is monitored by observing the color change to black and the turbidity17. The black color (FeS) is attributed to the conversion of the sulfate ion into the sulfide ion, which binds iron to form iron sulfide. The total number of colony-forming units (CFU) is counted using Eq. (7):

Surface study carried out using scanning electron microscope (SEM)-Microscope Unit, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt. High-resolution imaging (limit ~ 3–6 nm) was used to image the surfaces with a relatively large, focused sample depth. Energetic incident electrons (es) beams scan the sample surface, causing elastic scattering, and es are emitted from the sample surface. Emitted and back-scattered electrons formed the sample. Accurate information about biofilm morphology attained from SEM images by careful sample preparation: Micrographs validated the adherent biofilm to bare and coated brass surfaces and analyzed microbial diversity. The surface biofilm and corrosion features were examined after a week of exposure. The prepared samples were immersed in a 2% glutaraldehyde solution for one hour, then dehydrated at 4℃ through a graded series of ethanol washes, followed by drying, coating with thin-layer gold, and observation under a field-emission SEM. Small pieces of fresh bacterial specimens from the bacterial culture were centrifuged. Bacterial cells were fixed by immediate immersion in 4% formaldehyde (phosphate-buffered fixative, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 3 h. Further fixation in 2% OsO4 in the same buffer solution at 4 °C for two hours, washed with buffer, and dehydrated at 4 °C using a graded ethanol series, dried, and mounted using carbon-paste on an aluminum stub and coated with a gold layer, thickness 400 Å in a sputter–coating unit (JFC-1100 E)18.

Coating evaluation

MIC was monitored by using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The experiment setup is represented in Fig. SI.210. The charge transfer resistance of brass in wastewater monitored using the 3-electrodes: working (WE), reference electrode (RE), counter electrode CE) in artificial wastewater medium: CH3COONa, 1.0; NH4Cl, 0.2; CaCl2.2H2O, 0.15; KCl, 0.33; NaCl, 0.30; MgCl2, 3.15; K2HPO4, 1.26; KH2PO4, 0.42; yeast extract, 1.0, 1.0 mL trace metal solutions in tap water: FeCl2.4H2O, 50; ZnCl2, 1.25; MnCl2.4H2O, 12.5; (NH4)6Mo9O24.4H2O, 1.25; CoCl2.6H2O, 3.75; NiCl2.6H2O, 2.5; CuCl2.2H2O, 0.75; H3BO3, 1.2519. Figure 3. showed a waste seawater sample after one week of incubation at 25 °C.

The volume of the test solution was kept constant at 50 mL in all experiments. The surface area of the WE sample was 0.979 cm2. Potential of RE: Hg/Hg2Cl2(s), KCl(saturated)) was 0.242 V at 25℃. CE completed the electrical circuit, allowing the current to flow. RE is positioned closely to the WE surface to minimize the Ohmic IR drop and overvoltage across the solution. The cell and its components are carefully cleaned after each experiment using a chromic acid-H2SO4 mixture, washed with tap water, double-distilled water, and a portion of the test solution. The cell attained thermal equilibrium at 30℃ in an ultra-thermostate and was connected to a computerized ACM 604 Potentiostat/Galvanostat. Sequencer 604 software is used for experimenting. Version 4 of the ACM software was used in data analysis. Each electrode is inserted at the appropriate joint10.

The open-circuit rest steady-state potential of WE (EOCP/rest) is developed due to the electrical double layer (EDL) at the brass/solution interface, established for half an hour to ensure reliable impedance measurements at EOCP. WE surface polarized by applied peak-to-peak sine periodic excitation wave AC signal of 10 mV amplitude at a frequency range: 0.01 Hz to 10 10^4 Hz. Potentiostat-controlled (WE-RE) potential and recording of response current between CE and WE are using an impedance analyzer. The electrode potential is referred to the SCE. Cell components were cleaned after each experiment with tap water, double-distilled water, and the test solution9.

The ecotoxicological risk of organotin was assessed using the Spirulina platensis microalga algal strain, which was cultivated after sonication under a 10-W Visible LED lamp and subsequently harvested. Then, the algal biomass was separated by centrifugation at 400 rpm and screened from the broth, and subsequently thickened, dewatered, and dried. The biomass was assessed spectrophotometrically at 482 nm10.

Results and discussion

Coating characterization

Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of the organotin coating: Sn–Cl bond stretching vibrations around 615 cm⁻1, Sn–O bond stretching vibrations at 573 cm⁻1, Sn–N bond vibrations around 420 cm⁻1 (if nitrogen is coordinated), Free NH stretching at 3325 cm⁻1, and cyclic NH stretching at 3293 cm⁻1.

Figure 5 confirmed the polymeric amorphous structure of the organotin coating.

The crystallinity of cephradine decreased upon intercalation with Sn(II) ion. The amorphous structure of the organotin coating confirmed its polymeric structure.

Table 1 showed that polymeric organotin (II) complex coating of formula [Sn(tetra-dentate cephradine) Cl] showed lower MIC than native cephradine. It was insoluble in water and common organic solvents.

The significant antibacterial activity of organon Sn meperidine was stronger than that of cephalins Ab in terms of low MIC, except for Mirabelli’s and E. faecalis species. Variation in activity against different organisms depends on the impermeability of cell membranes (polymerization of the organotin coating improves lipophilicity, which favors permeation of the lipid layer) and the different ribosomes of various cells17.

Figure 6 shows that the organotin coating kills most of the bacteria in terms of total viable cells.

The cell viability of S.pyogenes is nearly diminished by the addition of the organotin, confirming its antibacterial activity. The synergistic binding of tin to cephradine enhanced antibacterial activity by participating in the disruption of biological processes in bacterial cells. Polymerized amphiphilic organotin coating improved compatibility and interaction with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic components of bacterial cell walls (a requirement for biocide coating)20,21.

The SEM micrograph confirmed the amphiphilic polymeric structure. The Rough surface of bare brass indicated a higher CR by SRB in waste seawater. Rapidly developed biofilms on brass surfaces in waste seawater created heterogeneous microenvironments that destabilize protective oxide layers through metabolism (producing organic acids, SRB reduced sulphate ions into hydrogen sulfide, and forming differential aeration electrochemical cells under the biofilm. Figure 7 shows that the brass alloy covered by SRB is pure Gram-negative short rods (reducing sulphates to sulphides). The blackening of the medium is attributed to the formation of insoluble iron sulfides when sulfide ions react with ferrous ions present in the culture medium.

Figure 8 shows the SRB, which causes localized pitting corrosion, resulting in holes on the metal surface. These holes may be small or large in diameter, but in most cases, they are relatively small in diameter.

Figure 9 shows the intense biofilm formation on brass in SRB media containing SnCl2.

The synergistic protection of Sn and cephraddine is confirmed in Fig. 10.

No pitting corrosion appears, and a continuous polymer coating film entirely covers the metal’s surface.

The biofilm contains various bacterial cells, which induce the formation of differential concentration and aeration cells, and generate corrosive substances11. The microbial cells associated with the brass surface are enclosed in a secreted extracellular polymeric gel (EPS) matrix. Major bacteria live and grow by utilizing EPS macromolecules, including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, metabolites, and other particulates from the surrounding environment. EPS establishes the integrity of biofilm structure and function, controlling both physicochemical and biological properties. EPS represented 90% of the biofilm-protected bacteria from biocides. The conditioning of the initial adherent biofilm altered the chemistry of the brass surface for facilitating the attachment of the microorganisms (MOs) that further excrete stable cohesive EPS, assisting in irreversible adherent attachment and micro colony formation, causing MIC11.

At the microenvironment of the brass/solution interface, pH increased, dissolved oxygen decreased, and the concentration of various inorganic and organic species differed from the bulk solution. The hybrid organometallic Sn completely isolated the brass surface from MIC. This coating is superior to organic or inorganic coatings (paints, lacquers, and coal tar) or (porcelain enamels, chemical-setting silicate cement linings, glass coatings, and linings)22.

Orthophosphate acts as a passivator and an anodic inhibitor, forming a porous copper phosphate film whose voids are filled by reduced Sn species, followed by adsorbed cephradine molecules. Orthophosphate was an excellent passivator in the presence of oxygen. The four electron donors, heteroatoms (O, N, S, P), are present in the prepared organotin coating. Their increasing order of corrosion inhibition efficiency followed the order: Oxygen < Nitrogen < Sulphur < Phosphorus.

Cephradine protected brass via physi- or chemisorption onto Cu/solution interface by removing molecules of water on the surface for compact barrier film formation23. The coordinate covalent bond formed by interaction between lone pair and π-es available in cephradine molecules with the vacant metal d-orbitals of tin is also involved. Nevertheless, compound adsorption on the metal surface is enhanced by the formation of p-d bonds. As a result, p-electrons overlap with the 3d vacant orbital of the Cu atom due to the availability of N, O, S atoms and π electrons of double bonds of organic cephradine molecules23. The protection and insulating dielectric properties of the organo-Sn coating are confirmed by the impedance Nyquist plots (Fig. 11).

Native brass showed Nyquist impedance spectra that consisted of a distorted semicircle followed by a diffusion tail, indicating that the corrosion mechanism was under diffusion control. The disappeared diffusion tail, which was replaced by a capacitive loop in the coating sample, confirmed the strong adsorption of the coating constituents on the brass surface and inhibition of the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction. The charge transfer controls MIC. The increase of the semicircle diameter at high cephradine concentration is attributed to the adsorption of its molecules at the metal/solution interface, that retarding the charge transfer process during copper oxidation (the slowest rate-determining step of MIC).

Nyquist spectra were analyzed by nonlinear fitting of the observed impedance data to the equivalent circuit model (Fig. 12).

The calculated parameters obtained from the equivalent circuit fitting analysis of the bare and coated samples. Due to the inhomogeneity of the corrosion system, capacitance is implemented as a constant phase element (CPE) during the analysis of the impedance plots. Two values, Q and n, define the CPE. The impedance, Z, of CPE is presented by Eq. (8):

where ω and f: frequency in rads−1 and Hz, respectively. For n = 1 for CPE capacitor, ZC = (iωC)−1, C = ideal capacitance. For a heterogeneous system, n ranges from 0.9 to 110.

The theoretical element (Rs) represented the solution resistance between WE and RE; Rf is the resistance of the coating film; Rct represents the charge-transfer resistance. Constant phase element Q1 is composed of the film capacitance CPEf and the deviation parameter n1, and Q2 is composed of the double-layer capacitance CPEdl plus the deviation parameter n2. Warburg impedance (W) caused a Warburg diffusion tail in the low-frequency range. Dissolved oxygen diffused from the bulk solution to the brass surface.

The impedance spectra were nonlinearly fitted to the equivalent semicircle model with a small error, as shown in Fig. 139.

The impedance parameters were given in Table 2.

The charge transfer resistance over the brass surface coated by organotin increased with increasing cephradine concentration from 0.0 to 0.0001.3. The presence of the bulky Ph group covered many active sites of the brass surface. The electron density on the multiple heteroatoms (S, N, O) increases the electron density at the main adsorption centers (-S–H).

The organotin coating was evaluated by anodic polarization after immersion in the test wastewater for a period of two months. Cu+2 ion leached with the corrosion product from the brass surface in an amount that depends on the applied current density. The mass-transfer-limiting current (iL) attained at high anodic overpotentials is attributed to a passive layer of copper oxide (CuO)9,10. After a two-month exposure to wastewater, the current–voltage curves are represented in Fig. 14.

The lowest current density on anodic polarization of the metal surface at a potential range (0.250 V–1.25 V), scan rate 60 mVmin−1.The blank bare metal sample showed the most significant current density.

Effect of cephradene concentration on the limiting current required for electropolishing. Applied potential (0.5–1.5 V) and current density recorded in Table 324:

Pitting corrosion after biofilm removal, confirming the existence of SRB and aerobic bacteria dominating the biofilm, Fig. 15.

Long-term performance and real-world applicability are confirmed by extended durability studies, which exceed six months, conducted under dynamic conditions. Figure 16 shows an SEM micrograph of a coated brass sample after immersion in a real seawater sample for seven months under the ambient aerated conditions:

Table 4 shows the optical density of the microalgae at 482 nm. Only high concentrations of 250 µgL−1 organotin affected the optical density of the algal biomass.

The large optical density of the spirulina microalga (cyanobacteria) in the presence of different concentrations of aged organotin indicated a decrease in cytotoxicity on the algal cells with aging, a time too long to be encountered in controlling MIC.

Mechanism of coating inhibition

The distorted tail semicircle (Nyquist impedance plot) in the blank brass sample exhibited a diffusion tail, indicating that the corrosion of copper is controlled by a cathodic oxygen reduction reaction, which proceeds to form H2O2, followed by either water reduction or direct reduction.

The suggested dissolution mechanism of brass is represented by Eqs. (9), (10) and (11)9,10:

Simultaneous copper oxidation is suggested as follows:

During the dissolution of active Zn in aerated wastewater, both hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions are possible. Since the saturated solubility of oxygen in pure water at 25 °C is 10−3 mol dm−3, it slightly decreases with increasing concentration of dissolved salts. Proton produced from bacterial metabolism (H3O+) is easily reduced at the brass/solution interface. Zn is oxidized by corrosive, acidic bacterial metabolites, as shown in Eqs. (12) and (13).

Soluble Zn(II) ion was in equilibrium with many Zn (hydroxides and oxides) species.

During the electroless deposition of a tin coating, tin coordinated with cephradene, forming a new polymeric hybrid coating. The coating filled the pores in the active sites on the brass surface.

Tin deposition involved crystal nucleation and growth. Cephradine Ab adsorbed on the surface of tin crystals enhanced crystal growth12,13. The newly formulated polymeric tin coating is a promising alternative to brass alloy in cooling systems, compared to common biocidal corrosion inhibitors such as benzotriazole and tetrakis-OH-CH3-phosphonium sulfate, which have been shown to mitigate MIC in Cu-Ni alloy completely but have not been reported for brass alloy25.

The mechanism of killing bacteria by organotin can be suggested as follows: interaction with essential cellular components and binding of organotin molecules to SH groups in bacterial proteins or enzymes. Hence, it disrupts their function, leading to cellular damage, the destruction of bacterial DNA, and ultimately, bacterial cell death; it also induces oxidative stress in bacteria.

Conclusion

This study confirmed the ease of formulating a new protective organotin coating for brass alloy against microbial corrosion by SRB. The coating was formulated using low-cost materials at feasible preparation conditions. Cephradine additive during electroless coating of Sn on brass alloy formed a polymeric organotin coating. The prepared anticorrosive protective coating formed a physical barrier at the brass/wastewater interface. Sn was a cathodic sacrificial coating to copper. Cephradine molecules are adsorbed and further adsorbed, reinforcing the metallic tin coating. This coated brass exhibited good corrosion resistance to MIC and is recommended as a low-cost coating for brass alloys used in water pipes. Organosn coating acts through numerous experimental studies, concluding that cephradine antibiotic, when bound to tin, increases its protective π-electrons, heteroatoms, and cathodic Sn coating. This is a new biocidal coating reported for brass alloy. Based on efficiency. The future work recommends the application of this formulation in organic paint coatings (for enhanced corrosion resistance) instead of antimicrobial agents (quaternary ammonium compounds and silver nanoparticles, which were not examined for brass alloys).

Data availability

"Data is provided within the manuscript file".

References

MacMahon, A.D., 1965. Copper: a materials survey (Vol. 8225). US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines.

Wang, K., Ju, Y. L., Lu, X. S. & Gu, A. Z. On the performance of copper foaming metal in the heat exchangers of pulse tube refrigerator. Cryogenics 47(1), 19–24 (2007).

Swain, G. W. J., Farrar, R. A. & Hutton, S. P. The use of controlled copper dissolution as an anti-fouling system. J. Mater. Sci. 17, 1079–1094 (1982).

Schütze, M., Roche, M. and Bender, R., Corrosion resistance of steels, nickel alloys, and zinc in aqueous media: Waste water, seawater, drinking water, high-purity water (2015)

Hong, S. H. et al. Recent development of coloring alloys. Prog. Mater Sci. 123, 100811 (2022).

Schock, M. R. & Neff, C. H. Trace metal contamination from brass fittings. J. Am. Water Works Ass. 80(11), 47–56 (1988).

Powell, C. and Webster, P., Copper alloys. In: Corrosion Performance of Metals for the Marine Environment EFC 63 (pp. 26–41). CRC Press. (2019)

Mattsson, E. Corrosion of copper and brass: Practical experience in relation to basic data. Br. Corros. J. 15(1), 6–13 (1980).

Elbatouti, M. & Fetouh, H. A. Extraction of eco-friendly and biodegradable surfactant for inhibition of copper corrosion during acid pickling. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 37(7–8), 649–663 (2019).

Wang, A. et al. Assessing the ecological risk of representative wastewater based on a growth inhibition method with freshwater algae (Raphidocelis subcapitata). Crop Health 1(1), 7 (2023).

Omar, S.H., Khalil, N.E., EL-Ahwany, A.M.D., El-Sayed, H.A.E. and Arafat, S.O.Y., Mitigation of Microbiologically Induced Corrosion (MIC) and Preventive Strategies. Research Trends of Microbiology (2021)

Murray, B. E. & Moellering, R. C. Jr. Antimicrobial agents in pulmonary infections. Med. Clin. North Am. 64(3), 319–342 (1980).

de León, C.P., Kerr, C. and Walsh, F.C., Electroless plating for protection against wear. Surface coatings for protection against wear, p.184 (2006)

Petro, R.A., Modern Applications of Novel Electroless Plating Techniques (2014)

Chaudhary, A., Phor, A., Agarwal, G. K. & Singh, R. V. Studies on Cephradine and its compounds with tin (II), lead (II), manganese (II), and iron (II). Heterocycl. Commun. 10(6), 393–398 (2004).

Mann, P. J., Wen, S., Xiaonan, Y. & Stevenson, W. T. A modified Ubbelohde viscometer with improved dilution characteristics. Eur. Polymer J. 26(4), 489–491 (1990).

ElTatawy, R. A., Ismail, A. M., Ayoup, M. S., Ismail, M. M. & Fetouh, H. A. Preparation and kinetic studies of a new antibacterial sodium alginate gelatin hydrogel composite. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29206 (2024).

Mohammed, A. and Abdullah, A., November. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM): A review. In: Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Hydraulics and Pneumatics—HERVEX, Băile Govora, Romania. 7–9 (2018)

Yang, L., Chang, W. S. & Huang, M. N. L. Natural disinfection of wastewater in marine outfall fields. Water Res. 34(3), 743–750 (2000).

Gleeson, B. et al. Novel organotin antibacterial and anticancer drugs. Polyhedron 27(18), 3619–3624 (2008).

Mazzaglia, A. et al. Supramolecular assemblies based on complexes of nonionic amphiphilic cyclodextrins and a meso-tetra (4-sulfonatophenyl) porphine tributyltin (IV) derivative: Potential nanotherapeutics against melanoma. Biomacromol 14(11), 3820–3829 (2013).

Hattawi, S. N. et al. New approach for processing chitosan as a low-cost protective hybrid coating for C-steel in acidic media. Heliyon 10(13), e34092 (2024).

Pryor, M. J. & Cohen, M. The mechanism of the inhibition of the corrosion of iron by solutions of sodium orthophosphate. J. Electrochem. Soc. 98(7), 263 (1951).

Silchenko, D. J. et al. Establishing the patterns in the anode behavior of copper in phosphoric acid solutions when adding alcohols. Bocтoчнo-Eвpoпeйcкий жypнaл пepeдoвыx тexнoлoгий 4(6), 35–41 (2018).

Chaitanya Kumar, K. & Appa Rao, B. V. Mitigation of microbially influenced corrosion of Cu–Ni (90/10) alloy in a seawater environment. Res. Chem. Intermed. 42, 5807–5823 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF, Science and Technology Development fund) in cooperation with Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Alexandria University provided funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manal A. El Sayed, Howida A. Fetouh contribute equally to the manuscript wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All authors approved the participation consent and confirmed that there were no ethical issues.

Consent for publication

Authors approved consent on publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sayed, M.A.E., Fetouh, H.A. Electroless deposition of effective biocide biofouling polymeric organo tin cephradine coating for brass alloy in wastewater. Sci Rep 15, 39375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23654-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23654-z