Abstract

Background Neurocognitive impairment is one of the serious treatment-related late complications of childhood cancer survivors (CCS). This study aimed to evaluate neurocognitive impairment of Korean CCS at their adolescent and young age for whom little was known. Method We recruited 720 Korean CCS diagnosed with primary cancer before the age of 19 years and 222 siblings of CCS. We measured neurocognitive function using the Korean version of Neurocognitive Questionnaire (K-NCQ) composed of four subdomains, with cut-off level of impairment set at the upper 10% of score distribution among sibling group. We evaluated the risk of neurocognitive impairment in CCS as compared with sibling by multiple logistic regression analysis. Results Average (standard deviation) ages of CCS at cancer diagnosis and at survey was 9.3 (5.3) and 17.6 (5.1) years, respectively. Compared with siblings, prevalence and adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of neurocognitive impairment were significantly higher in CCS with CNS solid tumor for task efficiency (31.5% vs. 16.2%, 2.58(1.47, 4.50)) and organization (24.1% vs. 13.5%, 2.70(1.44, 5.07)) subdomains. Consistent findings were observed in the subgroup analysis of 156 CCS with sibling participants and their siblings (n = 183). However, CCS with non-CNS solid tumor or hematologic malignancy showed no increased risk of impairment for four subdomains of K-NCQ. Conclusion Young-aged Korean CNS solid tumor survivors may have a higher risk of neurocognitive impairment for task efficiency and organization subdomains. However, neurocognitive function for memory and emotional regulation subdomains did not differ between CCS and siblings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As observed in Western countries1,2, the 5-year survival rate of Korean childhood cancer patients has markedly increased from 56.2% in 1993–1995 to 78.2% in 2007–2011, which results in around 1,100 new childhood cancer survivors (CCS) per a year3.

Meanwhile, compared with adult cancer survivors, CCS are more likely to face diverse negative health and quality-of-life consequences being related to the various late complications of intensive cancer treatment received at earlier age4. Neurocognitive deficit is often reported as one of the serious late complications of CCS5. Cancer itself as well as various cancer treatment modalities such as cranial radiation, neurosurgery, and chemotherapy are supposed to increase the risk of neurocognitive impairment in CCS5,6.

Several reports from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, a very large cohort study of CCS in the US and Canada (US cohort CCSS) including around 15,000 CCS, have revealed that one-third of adult CCS suffer from neurocognitive deficit such as learning difficulty, diminished intelligence, reduced executive function, difficulty in sustained attention, decreased memory processing speed, difficult emotional regulation, and impaired visual-motor integration7,8,9,10. Interestingly, a study from the US cohort CCSS showed that higher proportions of Asians or Pacific Islanders (203 adult CCS, mean age: 29.2 years) reported neurocognitive impairment than non-Hispanic White CCS (12,186 CCS, mean age: 31.5 years) did, for task efficiency (30.6% vs., 24.7%) and memory (32.1% vs. 25.3%) subdomains, although there was no statistically significant difference in the neurocognitive functioning score between the two groups.6) Considering the genetic, environmental, and cultural difference, study findings from CCS in Western populations may not be applicable to Asian CCS.

There are some Asian studies that assessed the function of CCS11,12,13. However, most of the Asian studies included small number of CCS and have scarcely compared the neurocognitive function of CCS with that of non-cancer control group. In addition, Asian studies have evaluated neurocognitive function of CCS by diverse methods across the studies and none of them assessed neurocognitive function using the same tool for the US cohort CCSS, which makes comparison of study findings difficult.

Therefore, we evaluated the neurocognitive function of Korean young-aged CCS using the Korean version of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study-Neurocognitive Questionnaire (CCSS-NCQ), as compared to the neurocognitive function of siblings as a non-cancer control group.

Methods

-

1.

Study design and study participants

The present study is a cross-sectional study, using data from an ongoing Korean CCS cohort study (KoCCS). The KoCCS recruited CCS who were diagnosed with any type of cancer or bone marrow disorders before the age of 19 and had completed primary cancer treatment at one of three tertiary care hospitals in South Korea between October 2017 and December 2021. The KoCCS also recruited the siblings and parents of the CCS participants when they visited the study center for follow-up cancer surveillance of CCS.

Among the participants of the KoCCS, 800 CCS and 246 siblings aged 7 years or older were selected for the present study. We excluded 5 CCS who did not receive chemotherapy, 4 CCS and 2 siblings whose neurocognitive questionnaire data were missing. We also excluded 71 CCS and 22 siblings who had a history of psychological, neurological, ear, and eye diseases that may affect neurocognitive function. Finally, a total of 720 CCS and 222 siblings were included in our analysis.

The present study was approved by the institutional review board of each institute. (IRB file number: 2017-08-024 at Samsung Medical Center, IRB file number: KC17ONDI0694 at The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, IRB file number: CNUHH-2017-159 at Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital). Caregivers or legal representatives of the child participants who are under 18 years of age signed a written informed consent form. Adult CCS and siblings provided informed consent on their own. All methods in the present study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

-

2.

Study variables

The present study used the data collected for KoCCS. Clinical information including the age at diagnosis, the age at the completion of treatment, and clinical data (cancer type, presence of metastasis, and treatment modalities including chemotherapy alone or in combination with surgery, radiotherapy, and stem cell transplantation) was collected through the review of medical records. We calculated time lapse since treatment completion. We classified 30 types of cancer diagnoses into four groups as follows: central nervous system (CNS) solid tumors (medulloblastoma, ependymoma, and glioma), non-CNS solid tumors (neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma), hematologic malignancies (acute lymphoblastic leukemia(ALL), acute myeloid leukemia, and lymphoma), and others (aplastic anemia, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis).

Information on sociodemographic characteristics such as age at first visit, sex, education level, main caregiver’s level of education, and the frequency of insomnia for both CCS and siblings was collected using a self-administered questionnaire. We classified the education level of CCS and siblings into five categories based on school attendance and school levels (6-3-3 in Korea): a non-schooler, elementary schooler, middle schooler, high schooler, and after graduating high school. We categorized caregiver’s level of education into three groups: high school graduate or lower, college graduate, and master’s degree or higher. We categorized frequency of insomnia per a week into four groups: none, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, and 5 days or more.

Neurocognitive function of CCS and siblings was measured using the Korean version of the CCSS-NCQ (K-NCQ) (supplementary Table 1)14. CCSS-NCQ was originally developed for St. Jude’s Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and demonstrated excellent reliability and high construct and concurrent validity as compared with 32 items of the Behavior Problem Index (BPI)15 and 18 items of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI)16 in adult survivors of the US cohort CCSS10,14.

Cronbach α for assessing the internal consistency of the K-NCQ was 0.91 for the total scale and between 0.74 and 0.89 for four subdomains14. Based on four subdomains (task efficiency, emotional regulation, organization, and memory) composed of 11, 8, 2, 4 item questions, respectively, K-NCQ reflects the neurocognitive function of CCS. Responses to each item question consists of three levels (1: never a problem, 2: sometimes a problem, and 3: often a problem) and summary score of each subdomain is calculated by adding up the responses to all relevant item questions. A higher score indicates worse functioning. Having a neurocognitive impairment in each subdomain of K-NCQ for the present study was defined if the score of a CCS was higher than the cut-off level for upper 10% score of 222 sibling participants, according to the US cohort CCSS study17.

-

3.

Statistical methods

We compared sociodemographic characteristics between CCS and sibling groups using the chi-square test and Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for categorical variables and the student’s t-test for numerical variables after excluding those with missing values for the relevant variables. We calculated the adjusted mean K-NCQ score of each subdomain by ANCOVA test after adjusting for sex, age at survey, education level, caregiver’s level of education, and insomnia frequency. We compared the mean K-NCQ scores of each subdomain between CCS and siblings by cancer types, using the t-test. We compared the proportion of neurocognitive impairment for each subdomain between CCS and siblings by cancer types, using the chi-square-test. We estimated the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to evaluate the risk of neurocognitive impairment in CCS as compared with siblings, using multiple logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, sex, education level, caregiver’s level of education, and insomnia frequency. The covariates were selected because their distribution was different between CCS and siblings (P-value < 0.1). Although there was no significant difference between CCS and siblings in our analysis, we included caregiver’s level of education as a covariate, because parental education level has been reported to be associated with intelligence quotient of children18.

We conducted subgroup analysis in CCS with sibling participants (n = 156) and their siblings (n = 183) to look at the possible effect of CCS without sibling participants to study results and presented the findings from the subgroup analysis in supplementary tables. We compared the sociodemographic characteristics of CCS with sibling participants with their siblings as well as CCS without sibling participants by the chi-square test and Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for categorical variables and the student’s t-test for numerical variables. We compared the mean K-NCQ scores and the proportion of neurocognitive impairment for each subdomain between CCS with sibling participants with their siblings by cancer types, using the t-test and chi-square test. We evaluate the risk of neurocognitive impairment in CCS with sibling participants as compared with their siblings, using generalized linear mixed model in which each family unit was included as a random effect, and other covariates (age, sex, education level, caregiver’s level of education, and insomnia) were included as fixed effects.

We considered P-values < 0.05 to be statistically significant, and all statistical tests were two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 720 CCS. The average age of 720 CCS at cancer diagnosis was 9.3 years (standard deviation (SD) 5.3, range 0–19) and the time lapse from treatment completion to survey was 7.2 years (SD 5.2). Hematological malignancy (49.4%) was the most common cancer type. All CCS had received chemotherapy with (75.6%) or without (24.4%) additional treatment modalities. Around one-third of CCS received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) combined with other treatment modalities. When we looked into the characteristics of CCS according the participation of their own siblings (supplementary Table 2), age at survey and educational level were lower and the proportion of HSCT recipient was higher in CCS with sibling participants, while other characteristics were similar between the two groups.

Table 2 compares the sociodemographic characteristics between CCS and siblings. The proportions of male, older age at survey, higher education levels, and the frequency of insomnia were greater among CCS than among siblings (P = 0.018). When we compared the sociodemographic characteristics between 156 CCS with sibling participants and their siblings (n = 183), similar findings were observed for sex, education level, while age at survey and insomnia frequency were similar between the two groups (supplementary Table 3).

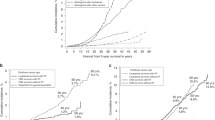

As presented in Fig. 1, the proportions of neurocognitive impairment between siblings and all CCS were not significantly different for all four subdomains of K-NCQ. However, there were significant differences in the proportions of impairment for task efficiency (p = 0.004) and organization (p = 0.05) subdomains of K-NCQ across the four different tumor types of CCS.

Proportion of neurocognitive impairment for subdomains of Korean version of the Neurocognitive Questionnaire. Figure. 1: P-values were obtained by chi-square test. *for comparing childhood cancer survivors (CCS) and their siblings. †for comparing among different types of tumor of CCS.

Table 3 presents the comparisons of K-NCQ scores for each subdomain between siblings and CCS according to cancer types. CCS with CNS solid tumor showed significantly higher scores (worse function) for task efficiency and organization subdomains of K-NCQ than their siblings. The proportions of impairment in task efficiency and organization subdomains of K-NCQ were also higher among CCS with CNS solid tumor than among siblings. Similar findings were observed in subgroup analysis in 156 CCS with sibling participants and their siblings (supplementary Table 4). On the other hand, CCS with hematologic malignancy showed lower score (better function) for emotional regulation subdomain of K-NCQ with borderline statistical significance (p = 0.059). The proportions of impairment in emotional regulation subdomain of K-NCQ was lower among CCS with hematologic malignancy than among siblings, also with borderline statistical significance (p = 0.051). There was no significant difference between siblings and CCS with CNS solid tumor in all four subdomains of K-NCQ.

Table 4 presents the aOR and 95% CI assessed by the multiple logistic regression analysis to evaluate the risk of neurocognitive impairment for four subdomains of K-NCQ in CCS by cancer types. Compared with siblings, CCS with CNS solid tumor were 2.70 times and 2.31 times more likely to have an impairment in task efficiency and organization subdomains of K-NCQ, respectively. CCS with other types of tumor showed no increased risk of neurocognitive impairment for all four subdomains of K-NCQ. These findings were consistently observed in subgroup analysis conducted in 156 CCS with sibling participants and their siblings (supplementary Table 5), even after the consideration of family effect and other covariates by the generalized linear mixed model.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study in Korean CCS and siblings revealed that CCS were more likely to have an increased risk of experiencing neurocognitive impairment compared with siblings, and the risk differed across K-NCQ subdomains and cancer types.

A systematic review including four Asian studies with neurocognitive function assessment reported that 10% to 28.0% of CCS with CNS tumors and leukemia had an impairment in the overall and perceptual intelligence12. In a more recent systematic review of 13 Asian studies, a mild-to-moderate degree of impairment in intelligence was found in 10.0 to 42.8% of CCS11, which appeared to be higher than the reported rate in Western CCS19. Although the methods for assessing neurocognitive function differ between the studies, these findings from ours and other Asian studies support that Asian CCS are also very likely to have an increased risk for neurocognitive impairment, as found in Western CCS studies.

In CCS with CNS tumors, both malignancy in the CNS itself and its treatment are known to cause cognitive impairment5,20. CNS-directed therapeutic modalities such as cranial radiation, intrathecal methotrexate, and neurosurgery have been associated with significantly worse performances of CCS on neurocognitive tests19,21. In the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study conducted in CCS after 18 years from the diagnosis of a CNS tumor, 11% of CCS who had not received radiotherapy exhibited long-term memory impairment, and CCS with craniospinal radiotherapy had a 2.7 times higher risk for intelligence impairment, 3.96 times higher risk for learning ability decrease, and 1.54 times higher risk for attention deficit20. A Korean study of 58 CCS with medulloblastoma reported 19%,12.1%,29.3%,and 39.7% of the CCS had lower full-scale IQ, verbal IQ, performance IQ, and memory quotient, respectively, by more than 1-standard deviation of average score22. However, in the Korean study, the neurocognitive function of CCS was not compared with that of non-cancer controls and covariates that may influence neurocognitive function of CCS were not considered. In our study, the risk for impairment in task efficiency and organizational subdomains in CCS with CNS solid tumor was significantly higher compared with siblings, even after adjusting for covariates such as educational level of CCS and main caregivers as well as insomnia frequency. A report from the US cohort CCSS study showed that adult CCS with CNS tumors (mean age: 31.5 years) were less competent in all four subdomains of CCS-NCQ than siblings17. Thus, findings for the impairment in task efficiency and organization are similar, while the findings for emotional regulation and memory subdomains differ between our Korean study and the US cohort CCSS study. Given the difference in age of CCS at survey and at diagnosis, ethnicity, culture and environment, treatment modality between the studies, additional studies seem necessary to establish the long-term risk for cognitive impairment in CCS with CNS tumor.

Chemotherapy given to CCS is also known to be associated with later cognitive impairment of CCS. Kanellopoulos et al. (2016) demonstrated that very long-term survivors of childhood ALL who had received chemotherapy showed lower scores in processing speed, executive function, and working memory than their peers, although they did not experience any decline in overall intelligence23. Chemotherapy may cause neurocognitive late effects through multifactorial mechanisms, including oxidative damage, white matter damage, inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis, decreased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and reduced blood flow or vascularization in the brain, as suggested in animal experiments24,25.

Despite the changes in treatment modality for childhood hematologic malignancy from high-dose radiation therapy to chemotherapy with low-dose irradiation for CNS prophylaxis, cranial radiotherapy itself may result in deleterious effects on the neurocognitive function of CCS19. Moreover, CCS who have received HSCT are likely to experience altered neurocognitive function, possibly due to the high-dose chemotherapy, myeloablative courses, as well as vascular and infectious complications during the post-transplant period26. A US cohort CCSS study in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood acute ALL (mean age: 15.4 years) showed that CCS were more likely to have inattention-hyperactivity (19% vs. 14%), learning problem (28% vs. 14%) compared with siblings27. Another US cohort CCSS study in adult (mean age: 30.8 years for male and 30.5 years for female) reported that CCS had an increased prevalence of impaired task efficiency (16.9% vs. 11.7% in males, 17.6% vs. 12.5% in females) and impaired memory (19.9% vs. 11.6% in males,25.4% vs. 14.8% in females) compared with siblings, although there was no difference in emotional regulation and organization subdomains28. A Korean study in 42 CCS of ALL (mean 10.5 years at survey) also reported that CCS had worse attention, concentration, and executive function than healthy controls13. However, in our study, CCS with hematologic malignancy did not show an increased risk of neurocognitive impairment, compared with siblings. In addition, the proportions of impairment in CCS (16.0% for task efficiency and 9.3% for memory subdomains) was relatively lower in our study than that observed in the US cohort CCSS study. Given the difference in time at cancer diagnosis of CCS between the US cohort CCSS participants (1970 ~ 1999) and our study participants (1994 ~ 2021), the changes in treatment modality overtime might explain the discrepancy of study findings at least in part. Therefore, further studies seem necessary to establish the risk, underlying mechanisms, and modifiable factors for cognitive impairment in CCS with hematologic malignancy.

Indirect effects such as chronic health conditions, health behaviors (including sleep, fatigue, and physical activity), environmental issues (including family functioning, parental pressure, and academic achievement), demographic factors, and genetic polymorphisms may influence neurocognitive function of CCS7,11. Sleep disturbance has been associated with worse cognitive flexibility in adult CCS, and the risk ratio was almost equivalent to that for high-dose radiation29. In the US cohort CCSS study in adult CCS, poor sleep quality was also identified as a risk factor significantly associated with task efficiency as well as memory problems29. In our study, we found that insomnia was more frequent among CCS than among siblings and, thus, we adjusted insomnia frequency as a covariate in analytical model in order to eliminate the influence of sleep disturbances on neurocognitive impairment. Even after that, CCS showed increased risks for impairment in task efficiency and organization subdomains. This finding seems to suggest that poor sleep quality of CCS may increase the risk of neurocognitive impairment but it does not fully explain the increased risk of neurocognitive impairment.

Findings from our study should be carefully interpreted with consideration of some limitations. First, this study was conducted using a cross-sectional design, which may not support establishing a temporal association. Second, we assessed neurocognitive function depending on self-administered questionnaire that may not be free of information bias, potentially leading to under- or overestimation of study estimates. Third, our study subjects may not represent all of Korean CCS, although we tried to overcome this issue by including a cancer center located in an area far from the capital city and the distribution of cancer type of our study participants is very similar to that reported by the Korea Central Cancer Registry3 Fourth, because of the relatively low mean age of CCS at survey, our study could not address the neurocognitive deficits occurring at a later point in life. Lastly, we tried to mitigate the confounding effect by including the education level of the CCS, as well as that of their main caregivers and sleep disturbances. We also tried to avoid the effects of diseases that may influence cognitive development, by excluding CCS with hearing loss, decreased vision, neurological diseases, and psychological disorders. We also look at the possible effect of CCS without sibling participants to study results by conducting subgroup analysis in CCS with sibling participants (n = 156) and their siblings (n = 183), which showed similar findings to the analysis in all study participants regarding the risk of neurocognitive impairment even after intra-family influence was considered using generalized linear mixed model. However, we could not consider other possible confounding factors such as physical activity, household income, genetic factors, and social environment. Thus, residual confounding could be possible.

Our study has some strengths, too. First, the present study included a large sample size of CCS compared to other previous Asian studies. Second, we included CCS with diverse types of cancer, which makes it possible to look into the risks of neurocognitive impairment across different types of cancer. Third, our study included siblings as a comparison group. Fourth, we assessed neurocognitive function using the K-NCQ, for which a validation study has been completed. By using K-NCQ, we could reasonably compare our study findings with the findings of the US cohort CCSS study.

In conclusion, in this Korean study including relatively young CCS with an average time lapse of 8.6 years from treatment completion, we found that CCS are more likely to have a neurocognitive impairment in task efficiency and organization subdomains compared with sibling group, most evidently among CCS with CNS solid tumor. These findings suggest that CCS have an increased risk for neurocognitive impairment after completion of cancer treatment, even from a relatively earlier age. Therefore, further studies to identify high-risk groups and to develop early effective interventional strategies to mitigate neurocognitive impairment in CCS seem necessary.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publically available, because the informed consents for current study did not include “sharing of study data with other researchers of data opening to public”, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sultan, I., Alfaar, A. S., Sultan, Y., Salman, Z. & Qaddoumi, I. Trends in childhood cancer: incidence and survival analysis over 45 years of SEER data. PLoS One. 20, e0314592. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314592 (2025).

Gatta, G. et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5–a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 15, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70548-5 (2014).

Park, H. J. et al. Incidence and survival of childhood cancer in Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. 48, 869–882. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2015.290 (2016).

Robison, L. L. & Hudson, M. M. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 14, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3634 (2014).

Hardy, S. J., Krull, K. R., Wefel, J. S. & Janelsins, M. Cognitive changes in cancer survivors. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 38, 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_201179 (2018).

Sato, S. et al. Functional outcomes and social attainment in Asian/Pacific Islander childhood cancer survivors in the united states: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 30, 2244–2255. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-21-0628 (2021).

Cheung, Y. T. et al. Chronic health conditions and neurocognitive function in aging survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx224 (2018).

Prasad, P. K. et al. Psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes in adult survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2545–2552. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.57.7528 (2015).

Castellino, S. M., Ullrich, N. J., Whelen, M. J. & Lange, B. J. Developing interventions for cancer-related cognitive dysfunction in childhood cancer survivors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106(8), dju186 (2014).

Krull, K. R. et al. Reliability and validity of the childhood cancer survivor study neurocognitive questionnaire. Cancer 113, 2188–2197. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23809 (2008).

Peng, L. et al. Neurocognitive impairment in Asian childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-020-09857-y (2020).

Poon, L. H. J. et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes in Asian survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 13, 374–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00759-9 (2019).

Kim, S. J. et al. Neurocognitive outcome in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: experience at a tertiary care hospital in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 30, 463–469. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.4.463 (2015).

Jeong, S. M. et al. Validation study of the Korean version of the neurocognitive questionnaire in the childhood cancer survivor study. Child. Neuropsychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2025.2494841 (2025).

Zill, N. & Peterson, J. Behavior Problems Index (Children Trends Inc, 1986).

Derogatis, L. R. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual (NCS Pearson, 2000).

Ellenberg, L. et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood CNS malignancies: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Neuropsychology 23, 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016674 (2009).

Sajewicz-Radtke, U. et al. Association between parental education level and intelligence quotient of children referred to the mental healthcare system: a cross-sectional study in Poland. Sci. Rep. 15, 4142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88591-3 (2025).

Krull, K. R., Hardy, K. K., Kahalley, L. S., Schuitema, I. & Kesler, S. R. Neurocognitive outcomes and interventions in Long-Term survivors of childhood cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2181–2189. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4696 (2018).

Brinkman, T. M. et al. Long-Term neurocognitive functioning and social attainment in adult survivors of pediatric CNS tumors: results from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 1358–1367. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2589 (2016).

Williams, A. M. et al. Childhood neurotoxicity and brain resilience to adverse events during adulthood. Ann. Neurol. 89, 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25981 (2021).

Yoo, H. J. et al. Neurocognitive function and Health-Related quality of life in pediatric Korean survivors of Medulloblastoma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 31, 1726–1734. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1726 (2016).

Kanellopoulos, A. et al. Neurocognitive outcome in very Long-Term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after treatment with chemotherapy only. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 63, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25690 (2016).

Vichaya, E. G. et al. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced behavioral toxicities. Front. Neurosci. 9, 131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00131 (2015).

Seigers, R. & Fardell, J. E. Neurobiological basis of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment: a review of rodent research. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 35, 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.006 (2011).

Harrison, R. A. et al. Neurocognitive impairment after hematopoietic stem cell transplant for hematologic malignancies: phenotype and mechanisms. Oncologist 26, e2021–e2033 (2021).

Jacola, L. M. et al. Cognitive, behaviour, and academic functioning in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Lancet Psychiatry. 3, 965–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30283-8 (2016).

van der Plas, E. et al. Sex-Specific associations between Chemotherapy, chronic Conditions, and neurocognitive impairment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 113, 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa136 (2021).

Clanton, N. R. et al. Fatigue, vitality, sleep, and neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer 117, 2559–2568. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25797 (2011).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1720270).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lee YS, Song YM, Shin DW, Sung KW, Lee JW, Baek HJ and Chung NG made substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition and analysis of data, or interpretation of study results; Lee YS, Jeong SM, and Song YM drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual contents; All authors listed approved the work to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensured that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, YS., Jeong, SM., Sung, K.W. et al. Risk for neurocognitive impairment in Korean childhood cancer survivors. Sci Rep 15, 39906 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23709-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23709-1