Abstract

Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC-P) is a very aggressive histopathological subtype of prostate cancer (PCa) that is strongly associated with poor clinical outcomes but for which no accurate biomarkers exist. Here, we demonstrate a novel application of texture analysis-based machine learning alongside multimodal nonlinear optical imaging using second-harmonic generation (SHG) and stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) at 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 Raman shifts to distinguish IDC-P from regular PCa and benign prostate. Images from each tissue type were analyzed to extract the first-order statistics and texture-based second-order statistics derived from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix of the images. A machine learning model was constructed using support vector machine (SVM) to classify the prostate tissue based on these statistics. Our results demonstrate that SVM models trained on either SHG or SRS images accurately classify IDC-P as well as high-grade PCa, low-grade PCa, and benign tissue with a mean classification accuracy exceeding 89%. Moreover, a mean classification accuracy of 98% was achieved using an SVM model trained on combined SHG and SRS images. Our study demonstrates that multimodal nonlinear optical imaging using SHG and SRS can be combined with texture analysis-based SVM classification to provide pathologists with a reliable biomarker of IDC-P.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) accounts for more than one-fifth of diagnosed cancers in males and is the third-largest cause of cancer death in Canadian men1. A particularly aggressive histopathological subtype of PCa is intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC-P). Morphologically, IDC-P is characterized by neoplastic cells confined within prostatic ducts and acini, exhibiting high-grade architectural patterns and pronounced nuclear atypia that resemble those observed in invasive adjacent carcinoma2. Clinically, the presence of IDC-P is strongly associated with elevated risks of metastasis and biochemical recurrence3. Driven by its reported low diagnostic reproducibility4,5, the ongoing debate surrounding the grading of IDC-P highlights the need for improved methods to better identify IDC-P and address this challenge. Given the poor clinical outcomes associated with IDC-P compared to less aggressive subtypes of conventional PCa, it is urgently necessary to provide pathologists with accurate biomarkers capable of discriminating IDC-P from regular PCa.

Nonlinear optical (NLO) imaging modalities have risen in prominence as diagnostic tools due to the non-ionizing and non-destructive nature of photon interactions and their ability to provide detailed biomolecular information at microscopic scales and high speed without the requirement for tissue staining dyes6,7. In particular, stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy is a proven NLO chemical imaging technique8,9 that utilizes infrared light to excite and produce images from the different vibrational modes of chemical bonds in biological samples. It has seen a multitude of applications including virtual histology10,11, in vitro12, and in vivo13 biological imaging. Second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy is another powerful NLO imaging technique that specializes in label-free collagen imaging14 due to its specificity in detecting only noncentrosymmetric structures and has been used to diagnose diseases such as cancer which alter collagen organization15,16,17.

SRS microscopy in the carbon-hydrogen (CH) stretching “high-wavenumber” region of the Raman spectrum has previously been used to evaluate cholesteryl ester content to differentiate low-grade and high-grade PCa18. It has also been used in the same spectral range to analyze cellular lipids and proteins for PCa Gleason scoring19, the grading system of PCa. SHG has similarly been applied for PCa grading based on collagen fiber architecture20,21,22 using techniques that evaluate the degree of collagen fiber orientation and alignment. However, neither of these imaging modalities have previously been used to identify IDC-P. Furthermore, none of these studies considered a multimodal approach combining SHG and SRS modalities to exploit their synergistic diagnostic potential.

Here, we applied a multimodal approach that investigated the use of SRS as well as SHG imaging to distinguish IDC-P from high-grade PCa (HGC, Gleason pattern 4 or 5), low-grade PCa (LGC, Gleason pattern 3) and benign prostate glands. Our work builds upon a previous work which identified Raman biomarker band information that is important for identifying IDC-P23. Based on this work, we collected SRS images at the 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 Raman shifts in the “fingerprint” region of the Raman spectrum, followed by SHG images of the same field of view (FOV) from 50 PCa tissue cores. Texture analysis24, a method that quantifies textural features of images based on gray-level differences, has previously been applied to the analysis of collagen and tissue organization for detecting cancer alongside a variety of NLO imaging modalities including SHG, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering, and two-photon excited fluorescence25,26,27. The goal of our study was to determine whether texture analysis-based features of PCa tissue extracted from SHG images and SRS images at the above Raman bands can be useful for the high-throughput identification of IDC-P.

By combining texture analysis, a technique that has never before been applied to SRS images, and support vector machines (SVM)-based classification, we show that both SHG and SRS microscopy imaging, when taken individually, can discriminate the four aforementioned types of tissue (IDC-P, HGC, LGC, benign prostate). Our work also demonstrates that higher classification accuracies can be achieved when the information from both modalities is combined into a single SVM model. These results lay the groundwork for future clinical applications of nonlinear optical imaging for diagnosing IDC-P and PCa, as well as hint to the biology of IDC-P.

Methods

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Human tissue samples

This study was approved by the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) ethics review board (reference number: 15.107). A cohort of 50 patients diagnosed with PCa who underwent first-line radical prostatectomy and participated in the Canadian Prostate Cancer Genome Project (CPC-GENE) was analyzed28. All patients signed an informed consent allowing for the use of their prostate tissue samples in research. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) radical prostatectomy specimens from these patients were used to construct tissue microarrays (TMAs). Two consecutive 4-µm tissue sections from each TMA block were cut and mounted onto glass slides (an H&E image from one such glass slide is shown in Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information S1). FFPE samples were used in this study because prostate cancer, including IDC-P, is often unpalpable and sparsely distributed, and embedding the whole prostate in paraffin enables more reliable detection than is possible with frozen sections or biopsies. The first sections underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining to detect α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR)/p63/34BE12, followed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) counterstaining29. The second sections were dewaxed and left unstained for SHG and SRS imaging. IHC-H&E slides were scanned using a whole-slide scanner (Nanozoomer, Hamamatsu). Images of selected regions were classified as IDC-P, LGC, HGC, or benign. IDC-P was identified according to Guo and Epstein established criteria and confirmed by IHC staining30. Images with invasive carcinoma were classified and annotated by a pathologist based on the highest Gleason grade in the image: LGC if they contained only Gleason grade 3 architecture, or HGC if any Gleason grade 4 or 5 patterns were present. Finally, images were classified as benign if they contained only benign glands. In total, IDC-P images were obtained from 18 patients, HGC from 28 patients, LGC from 15 patients, and benign images from 5 patients.

Multimodal NLO imaging

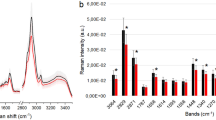

All experiments involving multimodal NLO imaging of prostate tissue samples were approved by the Carleton University Research Ethics Board (Project # 115118). The multimodal NLO images analyzed in this study were collected using a custom-built multimodal SRS microscopy platform. In this setup, an optical parametric oscillator system (Insight DS+, Spectra-Physics) provides a fixed laser output (“Stokes”; 1040 nm, ∼200 fs) and a tunable laser output (“pump”; 680–1300 nm, ∼130 fs) at a repetition rate of 80 MHz to target the Raman band of interest. As described in detail elsewhere31,32, the spectral focusing based SRS imaging platform employs a novel adjustable-dispersion glass blocks technology. The high refractive index (TIH53) glass blocks chirp the pump and Stokes pulses to 2.50 ps and 1.32 ps respectively, and the temporal delay between both excitation laser pulses is changed so that the instantaneous frequency difference matches that of the target Raman band. A 0.75NA 20X air objective (U2B825, Olympus) was used to image the tissue samples on regular microscope slides in transmission mode. The corresponding change in intensity of the pump beam due to stimulated Raman loss was measured as the SRS signal using lock-in detection. ScanImage (Version 5.6, Vidrio Technologies) was used to control laser scanning33. The SRS microscopy setup was modified to also collect SHG images by adding a longpass dichroic mirror with a cut-on wavelength of 450 nm (ZT1040dmbp, Thorlabs) to the output path that directed the second-harmonic light to another PMT (C14455-1560, Hamamatsu) as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Following the collection of the SRS images in the region of interest, the SHG images of the same FOV were collected by tuning the chirped pump laser to a wavelength of 830 nm. A time-averaged pump beam power of 65 mW at the sample was used to collect both the SHG and SRS images, while the SRS images also used a Stokes beam with a time-averaged power of 45 mW. The NLO imaging location was selected based on a side-by-side comparison of real-time 1450 cm−1 SRS images and the H&E image of the same sample core annotated by the pathologist (e.g. Figure 1b) for regions of IDC-P, HGC, LGC, and benign prostate. Each imaged location was additionally verified by a pathologist post-collection to ensure the tissue label assigned to the locations was accurate. The SRS images were collected in the fingerprint region at the Raman bands of 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1, corresponding to pump wavelengths of 904 nm and 886 nm. The 1450 cm−1 band represents the CH2 deformation vibrational mode with contributions from proteins and lipids while the 1668 cm−1 band represents the C = O stretch of the amide I vibrational mode with contributions from proteins34. These two Raman bands were chosen due to their known importance in classifying IDC-P and invasive PCa tissue23 in addition to their prominent peak heights providing a strong signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the SRS images relative to other Raman bands in the fingerprint region. The vibrationally resonant Raman signal in SRS images is typically accompanied by a non-vibrationally resonant background signal which arises due to optical effects such as cross-phase modulation, two-photon absorption, and thermal lensing35. To suppress the background contributions, off-Raman resonance images were also collected in the valleys between Raman peaks based on Raman spectroscopy data in the prostate tissue23 that represented only contributions from background effects. These off-Raman resonance images were collected at the Raman shifts of 1521 cm−1 (pump wavelength of 898 nm) and 1723 cm−1 (pump wavelength of 882 nm) corresponding to the on-Raman resonance images at 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 respectively. Images representing the vibrationally resonant Raman contribution were then obtained by subtracting the off-Raman resonance background image from the on-Raman resonance image. All SHG and SRS images were constructed by averaging 10 successively imaged frames at a resolution of 512 × 512. A pixel dwell time of 20 µs was used with a corresponding frame acquisition time of 5.2 s. The time required to acquire all SRS and SHG frames (in the following order: 1450 cm−1 on-resonance + off-resonance, 1668 cm−1 on-resonance + off-resonance, SHG) for one imaging location was approximately 6.5 min. Representative SHG and SRS images from the same 210 μm × 210 μm FOV in a prostate tissue core biopsy are shown in Figs. 1c–e and 2. A co-registered image of these SHG and SRS images is shown in Fig. 1f, showing the relative signal intensities of all three NLO channels. In total, data was collected from 201 FOV regions among the different cores.

Experimental setup schematic and workflow. In (a) the experimental setup, the pump and Stokes pulses are chirped by glass blocks (GB), combined at a dichroic mirror (DM), and scanned through an objective (OBJ) onto the sample (S) using galvanometer mirrors (GM). The light is then collected using a condenser (CON). Another dichroic mirror redirects the SHG light to the PMT, and the remaining light is collected in the SRS path after filtering the 1040 nm light and focusing it on the photodetector. (b) A representative annotated H&E image of a prostate tissue core with tissue regions annotated by a pathologist. HGC regions are shown in red and LGC regions in green, with the remainder being benign. Images were collected in the four regions demarcated by black squares on the core. The imaging process yields (c) 1450 cm−1 SRS images and (d) 1668 cm−1 SRS images after background subtraction, and (e) SHG images. (f) A co-registered image where SHG is shown in red, 1450 cm−1 SRS is shown in green, and 1668 cm−1 SRS is shown in blue. All the different multimodal NLO images (FOVs) are split into 3 × 3 subimages as shown in (g) to train and test an SVM (ECOC) model.

Representative images collected for different types of prostate tissue: IDC-P, HGC, LGC, and benign. The first column shows H&E/immunohistochemistry images for each tissue, and the three following columns show images of the same region acquired with SHG, with SRS at 1450 cm−1, and with SRS at 1668 cm−1. The final right-most column shows co-registered images where SHG is shown in red, 1450 cm−1 SRS is shown in green, and 1668 cm−1 SRS is shown in blue.

Texture analysis

To differentiate each different type of prostate tissue, the images were quantified using texture analysis based on first- and second-order statistics36. First-order statistics are directly derived from the gray-level pixel intensities of the image and do not consider the positioning of the pixels. In this study, the values of mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis are used as first-order statistics. Second-order statistics are instead derived from the spatial relations between the different pixels. Second-order statistics are therefore a method of quantifying the textures of the image, extracting information beyond the gray-level pixel intensity information used in first-order statistics. The spatial relations between the pixels are described by the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), which quantifies how often co-occurring pixel values appear with specific intensities at a given pixel offset36. For each image, GLCMs were calculated for four different one-pixel offsets (horizontal, vertical, diagonally up, diagonally down) after min-max normalizing the image to 128 Gy levels. To ensure that aberrant bright pixels did not influence the normalization, the top 1% of pixels were all assigned a gray level of 128. The second-order statistical parameters of contrast, homogeneity, energy, correlation, and entropy were then calculated by performing operations on the GLCM; an in-depth description of these statistical quantities can be found in Supplementary Information S2. Because the statistical quantities depend on the offset of the GLCM, each quantity was calculated for each of the four GLCM matrices and then averaged to yield a singular statistic.

Image segmentation for data analysis and FOV scoring

To increase the number of images to train and test on, all collected FOVs were split into a 3 × 3 grid (as shown in Fig. 1g), with a final count of 267 IDC-P subimages, 544 HGC subimages, 221 LGC subimages, and 46 benign tissue subimages. This corresponded to an FOV of 70 μm x 70 μm for the subimages, which is sufficient in scale to allow for the reliable measurement of texture-based features of multiple collagen fibrillar domains37 and soft tissue structures present within prostate tissue. A few FOVs contained more than one tissue type, in which case the image was split into two distinct FOVs corresponding to the different tissues. Other FOVs overlapped causing some of their subimages to coincide, in which case additional copies of a given subimage were removed. Due to the collagen imaged using SHG microscopy not always filling the entire image, split SHG subimages found not to contain enough collagen were discarded through a manual review. This approach excluded regions without any collagen texture that would therefore only add noise to the model. Fig. S2 in Supplementary Information S3 provides examples of subimage selection for the three above cases. The final count of SHG subimages came to 124 IDC-P subimages, 423 HGC subimages, 201 LGC subimages, and 34 benign tissue subimages. To account for the discrepancy in the number of subimages for each tissue type, the subimages were assigned learner weights such that the sum of all subimages for each tissue type had the same weight.

Multi-class discrimination of subimages and FOVs based on SVM model training

The SVM consisted of an error-correcting output code (ECOC) model in MATLAB R2024a. ECOC models enable multiclass learning by combining multiple binary SVM learners (one for each set of two classes) to construct a classifier. The ECOC model was trained using a polynomial kernel on the combination of 9 first- and second-order statistical parameters for each imaging modality (SHG and both SRS bands). The SVM model was trained to discriminate between the four basic types of prostate tissue: IDC-P, HGC, LGC, and benign tissue. The training and test sets were determined using a quasi-random splitting approach, where the imaged cores for each tissue type were randomly split in a 2:1 ratio. The subimages originating from these cores served as the training and test sets respectively. Splitting the training and test sets based on the prostate core of origin eliminated the intra-core bias that would arise from having tissues from the same core in both sets, and doing this split for each type of tissue ensured an equal representation of the tissue types in the training and test sets. This procedure was performed 10 times and the accuracy results from scoring the test set in each iteration were averaged to yield the final results. The accuracy is reported as a confusion matrix showing what percentage of subimages of a given tissue type (True class) are classified as a certain tissue type (Predicted class).

Multi-class discrimination of FOVs based on SVM model training

An alternative approach to taking the classification accuracy of the subimages is to determine how the FOVs (the original images before being split into 3 × 3) are classified by the model. This is done by finding the majority consensus (mode value) of the subimages composing each FOV. The approach of classifying the FOV, as opposed to each subimage individually, allows the SVM model to provide a definitive diagnosis for an imaged area. The results for the FOV majority-consensus classification accuracy are reported as a separate confusion matrix. In the event of a tie between two tissue types, the FOV was classified as the most aggressive tissue (IDC-P > HGC > LGC > benign tissue). The approach of FOV classification furthermore provides a convenient method of implementing a multimodal approach to image classification. The multimodal model returned the confusion matrix obtained from the aggregate majority consensus of both the SHG and SRS subimages for a particular FOV.

Feature selection

It sometimes occurs that certain statistical quantities do not end up having discriminatory power and are not useful for distinguishing different tissue types. When this is the case, these quantities only add noise to the model, decreasing its classification accuracy or potentially leading to over-fitting. To account for this possibility, one model was trained using all parameters, and then models were also trained where all parameters except one were present. When the exclusion of a parameter was found to increase the classification accuracy relative to the initial model, this parameter was excluded from the final model. The conditions under which these one-parameter-excluded models were trained were identical to the main model, that is to say, a 2:1 quasi-random split where the final results were averaged over 10 iterations. Two additional models were trained on only first- and second-order parameters only respectively to discern the relative importance of these parameters on classification accuracy for each imaging modality; the results from these models are shown in Supplementary Information S4.

Results

SHG and SRS images of prostate tissue expose distinct structures of cancerous and healthy prostate tissue

Representative images for IDC-P, HGC, LGC, and benign prostate imaged in the experiment are shown in Fig. 2. When comparing to the H&E images, it can be seen that the SHG images depict the collagen architecture of the imaged regions. The 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 SRS images are visually more similar to the H&E images since all components of the tissue contain the molecular signatures inherent to both SRS bands. When comparing both types of SRS images against one another, the 1450 cm−1 SRS images have higher SNR with stronger contributions from the stroma, and additional bright spots originating from lipofuscin granules18. In contrast, 1668 cm−1 SRS images show increased structural detail from protein contributions surrounding the stroma. Figure 2 also presents co-registered images which show the relative signal intensities of all three NLO channels.

First-order and second-order texture parameters exhibit statistically significant differences between IDC-P, HGC, LGC, and benign prostate tissue

Before training an SVM model based on the first- and second-order parameters, it is important to verify that statistical differences in those parameters are present between the different types of prostate tissue. This was done by using the Kruskal-Wallis test, a non-parametric ranked sum test that returns the p-value that different statistics come from the same distribution. The GLCM calculations and Kruskal-Wallis test were performed in MATLAB R2024a (Mathworks) for the SHG, 1450 cm−1 SRS, and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages. The test evaluated, for each pairing of tissues (for example, IDC-P versus HGC) and for each statistic derived from the subimages, the p-value that the statistics did not originate from a single distribution. The results are provided in Tables S2, S3, and S4 respectively in Supplementary Information S5, and generally indicate good discriminatory power between the different tissue types due to multiple statistics having statistically significant p-values (p < 0.05) for most tissue pairings. More statistically significant p-values were present in the tissue pairings for SHG subimages (69% of statistics) than in the 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages (54.8% of statistics) and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages (57.1% of statistics).

Having established that most statistics have statistically significant p-values, the process of feature selection determines which parameters are most important for classification for the SVM models. Comprehensive data showing the effects of the feature selection process are shown in Table 1. For the SVM model trained on SHG subimages, omitting the parameters of variance, skewness, kurtosis, or energy led to the one-parameter-removed model exceeding the classification accuracy of the baseline model, so these parameters were removed from the final SVM model. In the SVM model trained on 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages, all one-parameter-removed models exhibited lower overall classification accuracies, so all parameters were kept for the final SVM model. In the SVM model trained on 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages, omitting the parameters of mean and kurtosis increased the overall classification accuracy. Omitting the noisy parameters had the effect of increasing the overall classification accuracy of the SVM model trained on SHG subimages from 92.6% to 94.2%, and increasing the overall classification accuracy of the SVM model trained on 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages from 85.4% to 89.1%, a sizeable increase in both cases.

SHG and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages of prostate tissue can be accurately classified on the basis of first- and second-order parameters

The confusion matrices describing the classification accuracies of the subimages for the SVM models trained on SHG, 1450 cm−1 SRS, and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages are shown in Fig. 3a–c. The SVM model trained on SHG subimages reports high classification accuracies for subimages of each tissue type. Notably, the classification accuracies of HGC, LGC, and benign tissues all exceed 94%. However, there is a notable weakness in this model for detecting IDC-P, with 11.7% of IDC-P subimages being misclassified as HGC. This weakness can be linked to the Kruskal-Wallis test result for SHG subimages (Table S1), which returned high p-values for all statistics when comparing IDC-P and HGC. The classification accuracies for the SVM model trained on 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages are substantially lower than those of the SVM trained on SHG subimages, with a mean classification accuracy of only 49.3%. In contrast, the SVM model trained on 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages achieves classification accuracies similar to those of the SVM model trained on SHG subimages, with classification accuracies exceeding 92% for IDC-P and HGC tissues. However, this SVM model misclassifies 16.7% of benign tissue subimages as IDC-P and misclassifies 14.7% of LGC tissue as either HGC or IDC-P. This weakness can be linked to the Kruskal-Wallis result for the 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages, which showed IDC-P and benign tissues had only one statistically significant statistic.

Confusion matrices for classification of (a) SHG, (b) 1450 cm−1 SRS, and (c) 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages. The confusion matrices obtained when incorporating an FOV majority-consensus model are shown for (d) SHG, (e) 1450 cm−1 SRS, and (f) 1668 cm−1 SRS FOVs. The average classification accuracies of the central diagonal for each confusion matrix are 94.2% and 96.7% for the SHG models (subimage and FOV), 49.3% and 58% for the 1450 cm −1SRS models, and 89.1% and 92.6% for the 1668 cm −1 SRS models.

Majority consensus of subimages can be used to bolster SVM classification accuracy of FOVs

Incorporating an FOV majority-consensus model generally increases the classification accuracy for each tissue type (Fig. 3d-f). Most notably, the mean classification accuracy increased for each imaging modality, with the mean classification accuracy increasing from 94.2% to 96.7% for the SHG model, from 49.3% to 58% for the 1450 cm−1 SRS model, and from 89.1% to 92.6% for the 1668 cm−1 SRS model. In the case of the SVM model trained on SHG subimages, the number of IDC-P subimages classified as HGC is reduced from 11.7% to 6.9%, at the cost of a slightly higher fraction (5.9% to 6.3%) of misclassified LGC subimages. In the case of the SVM model trained on 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages, the majority-consensus model increases the classification accuracies of all categories, but still only achieves a low mean classification accuracy of 58%. For the SVM model trained on 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages, the classification accuracy for all cancerous tissues increases to above 92%, but the classification accuracy for benign tissue sees a slight decrease to 81.7%.

Multimodal SHG and SRS-based multi-class discrimination of FOVs based on majority consensus can be used to achieve a mean classification accuracy of 98%

Due to the low classification accuracy of the SVM model trained on 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages, the multimodal SHG + SRS model was implemented by using the SHG and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages. The multimodal model therefore classified the FOVs by evaluating the majority consensus of the combined SHG and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages taken in each particular FOV. The confusion matrix for the multimodal multi-class discrimination SVM model is shown in Fig. 4. It has nearly perfect accuracy, correctly classifying all tissues at accuracies exceeding 96%, and with an average classification accuracy of 98%. Notably, the multimodal SVM model has 2.6 times fewer IDC-P misclassifications than the SHG majority-consensus model (Fig. 3d) with an increase in classification accuracy from 93.1% to 97.4%. Moreover, it shows 8.7 times fewer misclassifications for benign tissue than the 1668 cm−1 SRS majority-consensus model (Fig. 3f) with an increase in classification accuracy from 81.7% to 97.9%. These increases in classification accuracy indicate that the multimodal SVM model mitigates the classification weaknesses of SVM models using only one modality.

Discussion

In this work, we developed a method to discriminate between subtypes of PCa tissue using an SVM model trained on texture analysis features extracted from SHG and SRS images at the 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 Raman bands. The first- and second-order statistics trained on by the SVM models showed a high proportion of low p-values when using the Kruskal-Wallis test, indicating the high discriminatory power of the statistics.

The SVM model trained on SHG subimages reported high classification accuracies for each tissue type (> 88%) that were even further improved after implementing FOV majority-consensus classification (> 93%). Using an FOV majority consensus improved the results by reducing the percentage of misclassifications of IDC-P as HGC from 11.7% to 6.9%. The high mean classification accuracies of 94.2% with subimages and 96.7% with FOV majority-consensus are consistent with the established potential of SHG for PCa grading20,21,22. However, in contrast to these prior studies, our SHG results establish the potential of SHG to identify IDC-P on top of achieving accurate grading for regular PCa, suggesting that changes in collagen architecture can be considered a reliable biomarker for IDC-P.

In a previous study, Raman bands in the fingerprint region demonstrated highly similar spectral profiles for IDC-P and adjacent invasive carcinoma, suggesting comparable biochemical compositions and shared tumor biology23. Both IDC-P and associated invasive adjacent carcinoma frequently harbor the same genetic alterations, such as TMPRSS2-ERG fusions and PTEN deletions, the latter being a hallmark of aggressive disease38,39,40,41. Importantly, this earlier Raman analysis focused exclusively on single epithelial cells (rectangular area of 24 µm2)23, whereas the current study expands upon these findings by incorporating both epithelial and stromal components (square area of 210 µm2). This broader approach not only enabled us to distinguish between IDC-P and the immediately adjacent PCa but also aligns with emerging evidence of the biology of the microenvironment of IDC-P showing differences in immune cell infiltration between PCa and IDC-P42. The integration of epithelial and stromal analyses in our study provides a more comprehensive perspective, potentially reflecting variations in the tumor microenvironment, including immune cell dynamics, that may influence their distinct biological and clinical behaviors.

The SVM model trained on 1450 cm−1 SRS subimages demonstrated much lower classification accuracies when compared to the SVM models trained on SHG and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages. The low classification accuracies disqualify the possibility of using SRS images at the 1450 cm−1 Raman band for PCa grading and identification of IDC-P. However, the fact that the 1668 cm−1 Raman band was successful in contrast to the 1450 cm−1 band permits us to infer that the chemical bonds targeted by the 1668 cm−1 SRS band provide textural information that is useful for classifying cancerous and non-cancerous tissue that is not present in the 1450 cm−1 band. Figure 2 shows the micromorphology in these two types of SRS images highlighting the different textural contributions of the two bands. In the 1668 cm−1 SRS image, the structure of the protein contributions surrounding the stroma is more detailed than in the 1450 cm−1 SRS image, despite the decreased SNR. Therefore, a probable reason for the success of the 1668 cm−1 SRS band is that the detailed cellular textures provide more discriminatory power. The success of the 1668 cm−1 band in contrast to the 1450 cm−1 band also highlights that only specific chemical components of the tissue, and therefore only images taken at certain Raman bands, can be used to discriminate cancerous and non-cancerous tissue types. These results once again highlight the importance of stromal differences between IDC-P and PCa.

H&E images are the clinical standard for prostate cancer diagnosis and have also been used in the past with GLCM and SVM for prostate cancer classification43. However, our approach offers key advantages. SRS and SHG provide label-free, quantitative imaging of molecular and structural features, and are therefore suitable for reproducibility and automation. Furthermore, the chemical information captured in SRS, which is known to be important in classifying IDC-P23, is not visible in H&E. As a result, the structural information of the collagen seen with SHG alongside the chemical information provided by SRS may improve discrimination beyond what is possible when using H&E alone. Our method can also be performed on glass slides before a final staining, expanding the range of tools available in digital pathology.

During feature selection, the classification accuracy of both SVM models trained on SRS subimages sees an unexpected decline when the parameter of variance is omitted, with the accuracy of the 1450 cm−1 SRS SVM model decreasing by 14.8% and the accuracy of the 1668 cm−1 SRS SVM model decreasing by 29.4%. An explanation for the relative importance of the variance in these models is that the second-order parameters are correlated with one another: with only first-order parameters, the model achieves a classification accuracy of only 29.3%, as shown in Table S1 in Supplementary Information S4. Unlike the SHG images, which are composed purely of collagen, the stromal SRS images are a combination of collagen and soft tissue. Since the collagen generally has a stronger signal than the soft tissue, a high variance is expected when both collagen and soft tissue are present while a low variance value is expected when there is only soft tissue. The variance may therefore be important for the SVM models trained on SRS subimages due to its ability to quantify the collagen to soft tissue ratio in the subimages.

While the individual SVM models trained on SHG subimages and 1668 cm−1 SRS subimages demonstrated a weakness at classifying IDC-P and benign tissue respectively, the multimodal SVM model incorporating the results of both SVM models does not demonstrate either shortcoming and provides a nearly perfect 98% average classification accuracy. The multimodal model therefore combines the classification strength of SHG for benign tissue and the classification strength of SRS for IDC-P. The lowest classification accuracy in the multimodal SVM model is 96.6% for LGC tissue, reflecting that the SHG image and 1668 cm−1 SRS image SVM models both had LGC as their second least-accurate classification category. This lower accuracy may be attributable to LGC regions being in proximity to HGC. However, the LGC classification percentage of the multimodal SVM model still considerably exceeds those obtained by the SHG majority-consensus model (93.7%) and 1668 cm−1 SRS majority-consensus model (92.0%), demonstrating the considerable benefit of a multimodal approach.

The results exhibited in this paper involved imaging SRS bands in the fingerprint region (800–1800 cm−1), building on previous work that demonstrated for the first time that several Raman bands in the fingerprint region had the potential to discriminate IDC-P from cancerous and benign tissue23,44. However, Raman bands in the CH stretching high-wavenumber region (2800–3100 cm−1) are typically more convenient to image using SRS due to the much higher density of CH bonds giving rise to a stronger SRS signal and therefore higher SNR. Potential Raman bands of interest in the CH region include the lipid, overlapping protein and lipid, and DNA bands located at 2850 cm−1, 2926 cm−1, and 2970 cm−1 respectively. A convolutional neural network trained on SRS images at the lipid and mixed protein and lipid bands demonstrated a Gleason scoring accuracy of 84.4%; this suggests that these bands could also be useful for detecting IDC-P19, and that as IDC-P appears globally similar to adjacent PCa, subtle differences between the two entities are still present. We anticipate that our approach based on textural analysis of SHG and SRS images when extended to the Raman bands in the high-wavenumber region will have the advantage of providing > 95% classification accuracy of IDC-P at significantly reduced (at least 2x lower) image acquisition times due to the increased SNR. The set of images used in this experiment included a low proportion of benign tissue due to the reclassification of some tissue as cancerous by pathologists following data collection. While the current study provides compelling results showing that texture analysis is fully capable of classifying benign tissue from cancerous tissues, future studies will expand the assortment of benign images to further bolster this claim. In this work, we used the widely established method of combining GLCM-based texture statistics with SVM due to the proven success of this model alongside SHG-based collagen imaging36. However, other methods such as convolutional neural networks, especially when using data augmentation methods to mitigate the effects of smaller datasets, have also been proven to be strong tools for classification of multimodal images and represent a potential future avenue of research for classifying IDC-P45.

A conclusive diagnosis of IDC-P is reported to be difficult for pathologists due to subjective diagnostic criteria and a lack of available biomarkers4. The results we present in this paper exhibit that NLO imaging techniques based on SHG and SRS imaging can be combined with texture analysis and SVM classification to provide pathologists with a reliable biomarker of IDC-P. Notably, both SHG and SRS (1668 cm−1) imaging modalities individually demonstrated high classification accuracies, while nearly perfect classification accuracies were achieved by combining both modalities. The clear benefit obtained from using two imaging modalities to classify IDC-P further highlights the potential of multimodal SHG + SRS acquisitions in a clinical setting. By using 4 μm FFPE tissue sections and standard glass slides, our method is also compatible with conventional histopathological workflow, and the non-destructive nature of NLO allows for performing any routine stain after imaging the slide23. Avenues for future research involve expanding these methods to a broader set of data for further validation and clinical applications such as an intraoperative handheld probe for the diagnosis of disease from prostate cores obtained in vivo.

Data availability

The raw data for the images used in this study, including the SHG images, 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 SRS on-resonance and off-resonance images, as well as background-subtracted 1450 cm−1 and 1668 cm−1 SRS images, are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Brenner, D. R. et al. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2020. CMAJ. 192, E199–E205 (2020).

Humphrey, P. A., Moch, H., Cubilla, A. L., Ulbright, T. M. & Reuter, V. E. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part B: Prostate and bladder tumours. Eur. Urol. 70, 106–109 (2016).

Pantazopoulos, H. et al. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate as a cause of prostate cancer metastasis: A molecular portrait. Cancers (Basel). 14, 820 (2022).

Iczkowski, K. A. et al. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate: Interobserver reproducibility survey of 39 urologic pathologists. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 18, 333–342 (2014).

Varma, M. et al. Intraductal carcinoma of prostate reporting practice: A survey of expert European uropathologists. J. Clin. Pathol. 69, 852–857 (2016).

Parodi, V. et al. Nonlinear optical microscopy: From fundamentals to applications in live bioimaging. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 585363 (2020).

Pallen, S., Shetty, Y., Das, S., Vaz, J. M. & Mazumder N. Advances in nonlinear optical microscopy techniques for in vivo and in vitro neuroimaging. Biophys. Rev. 13, 1199–1217 (2021).

Cheng, J-X. & Xie, X. S. Vibrational spectroscopic imaging of living systems: An emerging platform for biology and medicine. Science 350, aaa8870 (2015).

Hu, F., Shi, L. & Min, W. Biological imaging of chemical bonds by stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Nat. Methods. 16, 830–842 (2019).

Lee, M. et al. Recent advances in the use of stimulated Raman scattering in histopathology. Analyst 146, 789–802 (2021).

Ma, L., Luo, K., Liu, Z. & Ji, M. Stain-free histopathology with stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Anal. Chem. 96, 7907–7925 (2024).

Hill, A. H. & Fu, D. Cellular imaging using stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Anal. Chem. 91, 9333–9342 (2019).

Lin, P. et al. Volumetric chemical imaging in vivo by a remote-focusing stimulated Raman scattering microscope. Opt. Express. 28, 30210–30221 (2020).

Mostaço-Guidolin, L., Rosin, N. L. & Hackett, T-L. Imaging collagen in scar tissue: Developments in second harmonic generation microscopy for biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1772 (2017).

Keikhosravi, A., Bredfeldt, J. S., Sagar, A. K. & Eliceiri, K. W. Second-harmonic generation imaging of cancer. Methods Cell. Biol. 123, 531–546 (2014).

Tilbury, K. & Campagnola, P. J. Applications of second-harmonic generation imaging microscopy in ovarian and breast cancer. Perspect. Medicin Chem. 7, 21–32 (2015).

Mirsanaye, K. et al. Machine learning-enabled cancer diagnostics with widefield polarimetric second-harmonic generation microscopy. Sci. Rep. 12, 10290 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Hyperspectral stimulated Raman scattering microscopy facilitates differentiation of low-grade and high-grade human prostate cancer. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 484001 (2021).

Ao, J. et al. Stimulated Raman scattering microscopy enables Gleason scoring of prostate core needle biopsy by a convolutional neural network. Cancer Res. 83, 641–651 (2023).

Ling, Y. et al. Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of cancer heterogeneity in ultrasound guided biopsies of prostate in men suspected with prostate cancer. J. Biophotonics. 10, 911–918 (2017).

Ageeli, W. et al. Characterisation of collagen re-modelling in localised prostate cancer using second-generation harmonic imaging and transrectal ultrasound shear wave elastography. Cancers (Basel). 13, 5553 (2021).

Garcia, A. M. et al. Second harmonic generation imaging of the collagen architecture in prostate cancer tissue. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express. 4, 025026 (2018).

Grosset, A-A. et al. Identification of intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on tissue specimens using Raman micro-spectroscopy: A diagnostic accuracy case–control study with multicohort validation. PLoS Med. 17, e1003281 (2020).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern : Syst. SMC. 3, 610–621 (1973).

Wen, B. L. et al. Texture analysis applied to second harmonic generation image data for ovarian cancer classification. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, 096007 (2014).

Legesse, F. B., Medyukhina, A., Heuke, S. & Popp, J. Texture analysis and classification in coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy images for automated detection of skin cancer. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 43, 36–43 (2015).

Uckermann, O. et al. Label-free multiphoton imaging allows brain tumor recognition based on texture analysis-a study of 382 tumor patients. Neuro oncol. Neuro oncol Adv 2, vdaa035 (2020).

Fraser, M. et al. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature 541, 359–364 (2017).

Grosset, A-A. et al. Hematoxylin and eosin counterstaining protocol for immunohistochemistry interpretation and diagnosis. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 27, 558–563 (2019).

Guo, C. C. & Epstein, J. I. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy: Histologic features and clinical significance. Mod. Pathol. 19, 1528–1535 (2006).

Gagnon, J. R. et al. Spectral focusing-based stimulated Raman scattering microscopy using compact glass blocks for adjustable dispersion. Biomed. Opt. Express. 14, 2510–2522 (2023).

Allen, C. H. et al. Investigating ionizing radiation-induced changes in breast cancer cells using stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 28, 076501 (2023).

Pologruto, T. A., Sabatini, B. L. & Svoboda, K. ScanImage: Flexible software for operating laser scanning microscopes. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2, 13 (2003).

Movasaghi, Z., Rehman, S. & Rehman, I. U. Raman spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 42, 493–541 (2007).

Luca, Genchi, S. P. L. & Liberale, C. Background signals in stimulated Raman scattering microscopy and current solutions to avoid them. Adv. Physics: X. 8, 2176258 (2023).

Mostaço-Guidolin, L. B. et al. Collagen morphology and texture analysis: From statistics to classification. Sci. Rep. 3, 2190 (2013).

Rivard, M. et al. Imaging the noncentrosymmetric structural organization of tendon with interferometric second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Biophoton. 7, 638–646 (2014).

Lotan, T. L. et al. Cytoplasmic PTEN protein loss distinguishes intraductal carcinoma of the prostate from high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod. Pathol. 26, 587–603 (2013).

Schneider, T. M. & Osunkoya, A. O. ERG expression in intraductal carcinoma of the prostate: Comparison with adjacent invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 27, 1174–1178 (2014).

Morais, C. L. et al. Utility of PTEN and ERG immunostaining for distinguishing high-grade PIN from intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 39, 169–178 (2015).

Downes, M. R., Satturwar, S., Trudel, D. & van der Kwast, T. H. Evaluation of ERG and PTEN protein expression in cribriform architecture prostate carcinomas. Pathol. Res. Pract. 213, 34–38 (2017).

Diop, M-K. et al. Leukocytic infiltration of intraductal carcinoma of the prostate: An exploratory study. Cancers (Basel). 15, 2217 (2023).

Brancato, V. et al. Unveiling key pathomic features for automated diagnosis and Gleason grade estimation in prostate cancer. BMC Med. Imaging. 25, 299 (2025).

Plante, A. et al. Dimensional reduction based on peak fitting of Raman micro spectroscopy data improves detection of prostate cancer in tissue specimens. J. Biomed. Opt. 26, 116501 (2021).

Huttunen, J. et al. Automated classification of multiphoton microscopy images of ovarian tissue using deep learning. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 066002 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the University Health Network team for providing the TMAs, and Dr. Nazim Benzerdjeb MD who created the TMAs. We thank the molecular pathology core facility and Mirela Birlea of the CRCHUM for help in preparing prostate sections. The authors acknowledge the support of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (funding reference number PJT-169164), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (funding reference number RGPIN-2022-04897) (SM). Dr. Dominique Trudel receives salary support from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec, Santé (FRQS, Clinical Research Scholar, Senior). The CRCHUM also receives support from the FRQS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JRG and CHA imaged the prostate cores. JRG performed the data analysis. FD and FL helped conceive the methods in the data analysis. JRG, SM, DT and MK-D wrote the main manuscript text. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. SM, DT and FL conceived the idea and supervised the work. All authors took part in the revision process and approved the final copy of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gagnon, J.R., Allen, C.H., Diop, MK. et al. Label-free histological identification of intraductal carcinoma of the prostate using texture analysis-based multimodal stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Sci Rep 15, 39874 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23780-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23780-8