Abstract

Mimosa pigra L. is a globally significant invasive species that threatens wetland and agricultural ecosystems across the tropics. This study models its population density (plants per square meter) in northeastern Thailand using Bayesian Poisson and negative binomial regression, incorporating soil physicochemical properties as predictors. Data were collected from 50 plots across three districts in Maha Sarakham Province, with analyses of soil pH, organic matter, phosphorus, potassium, and electrical conductivity. Model performance was assessed via the Leave-One-Out Information Criterion (LOOIC) and posterior predictive checks. The negative binomial model provided a superior fit by capturing overdispersion, identifying potassium concentration, soil texture classes (e.g., clay loam, sandy clay), stem diameter, and soil structure as key determinants of M. pigra density. This work represents the first Bayesian quantification of edaphic drivers of M. pigra in Southeast Asia, demonstrating the utility of Bayesian count models for invasion ecology and offering practical guidance for habitat prioritization, early detection, and targeted management in high-risk floodplain ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive alien plant species (IAPS) are among the most critical global threats to biodiversity, ecosystem integrity, and agricultural productivity1,2,3. Mimosa pigra L., a nitrogen-fixing shrub native to tropical America, has emerged as one of the world’s most aggressive invaders due to its rapid growth, prolific seed production, and ability to form dense monospecific stands that displace native vegetation and disrupt ecological processes4. In Southeast Asia, particularly within Thailand’s Chi River Basin, M. pigra has rapidly expanded across wetlands and disturbed areas, intensifying ecological degradation and agricultural challenges.

While climatic factors are often emphasized in invasion ecology, local edaphic conditions–such as pH, organic matter (OM), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and electrical conductivity (EC)–are key determinants of species establishment, resource acquisition, and competitive interactions at fine spatial scales5. Nutrient enrichment, particularly of nitrogen and potassium, can increase ecosystem susceptibility to invasion by enhancing plant growth and competitiveness3,6. Previous studies in Australia have shown that soil fertility and nutrient availability directly influence M. pigra establishment and management outcomes7,8,9, yet similar quantitative studies remain scarce in Southeast Asia.

The Chi River Basin in northeastern Thailand, a major sub-basin of the Lower Mekong Basin, is characterized by extensive floodplains with acidic, nutrient-poor soils interspersed with agricultural landscapes, providing an ideal setting to investigate edaphic controls on invasion risk. Some potentially relevant variables, such as soil moisture and anthropogenic disturbance, were excluded from this study due to logistical challenges in obtaining standardized, comparable measurements across all field plots; this limitation is further addressed in the Discussion.

Modeling invasion risk is statistically challenging because ecological field data are often discrete, skewed, and overdispersed. Conventional regression models or correlative species distribution models may not fully capture these complexities. Bayesian methods provide a flexible and robust framework for analyzing ecological count data, offering advantages such as explicit uncertainty quantification, integration of prior information, and improved handling of overdispersion and zero inflation10,11,12. Bayesian Poisson and negative binomial models, in particular, enable more accurate inference and predictive modeling of species abundance distributions.

Although the biology, ecology, and control strategies of M. pigra have been widely studied13,14,15, quantitative assessments of how soil nutrients and physical properties influence its local abundance remain limited, especially in Southeast Asia. Addressing this gap is critical for advancing predictive invasion ecology and designing targeted, soil-based management strategies.

In this study, we apply Bayesian Poisson and negative binomial count models to examine the influence of soil physicochemical properties on M. pigra density across 50 systematically sampled plots in the Chi River Basin, northeastern Thailand. The objectives are to (1) identify key soil-related predictors associated with invasion risk, (2) evaluate model performance using information-theoretic metrics, and (3) provide evidence-based recommendations for monitoring and managing high-risk habitats. This work also highlights the practical value of Bayesian modeling for ecological forecasting, particularly in data-limited or heterogeneous environments.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the study area, field sampling strategy, and Bayesian modeling framework; Section 3 presents model estimates, diagnostics, and comparative performance metrics; Section 4 interprets findings in the context of invasion ecology and management, and Section 5 provides key conclusions and recommendations.

Materials and methods

Study area

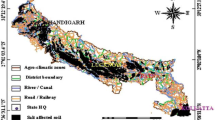

This research was conducted in Maha Sarakham Province, northeastern Thailand, encompassing three districts: Mueang Maha Sarakham, Kantharawichai, and Kosum Phisai. The study area is situated within the Chi River Basin, a lowland floodplain characterized by nearly level to gently undulating terrain, with slopes of 1–5% and predominantly flat to almost flat landforms. According to the Thai Meteorological Department16, Maha Sarakham has a tropical monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of approximately 27–28 \(^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) and a mean annual precipitation of 1,200 to 1,400 mm, concentrated during the southwest monsoon (May - October) and followed by a pronounced dry season (November - April).

Soils in Maha Sarakham area are predominantly sandy and inherently low in fertility, as documented by the Department of Mineral Resources17. Land use is dominated by rice cultivation, followed by sugarcane and cassava production, interspersed with wetlands and disturbed agricultural margins. These edaphic and land-use conditions create heterogeneous ecological niches that favor the establishment and proliferation of invasive species such as M. pigra, increasing the likelihood of its spread into adjacent habitats and contributing to broader ecological invasion dynamics.

Sampling plots systematically established in three districts of Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. The base map was created by the authors using QGIS (QGIS Development Team, QGIS Geographic Information System, Software version 3.40, https://qgis.org)18.

Data collection and soil analysis

At each of the 25 selected sites, two 2 m \(\times\) 2 m plots were established, yielding a total of 50 sampling plots. This sampling design captured a broad range of ecologically diverse microhabitats suitable for M. pigra establishment, thereby improving the representativeness and generalizability of the study findings. Plant density was measured by counting all M. pigra individuals within each plot. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of the plots in relation to hydrological features and surrounding land use, with plot details summarized in Table 1.

For soil sampling, five stations were randomly selected per plot, and three soil cores were collected at each station in a triangular arrangement. All cores from a plot were composited into a single sample for physicochemical analysis. Samples were collected from a depth of 0 - 30 cm and stored in sealed plastic bags to maintain moisture. Soil organic matter (OM) content was determined using the Walkley-Black wet combustion method19.

Key physicochemical parameters, including pH, available phosphorus (P), exchangeable potassium (K), and electrical conductivity (EC), were also measured due to their well-documented influence on plant growth, nutrient availability, and competitive interactions. Soil texture and structure were classified according to the USDA soil methodology and field protocols described in the Soil Survey Manual20, ensuring consistency with internationally recognized standards. Available phosphorus was determined using the Bray II extraction method21, exchangeable potassium was measured via ammonium acetate extraction followed by flame photometry and atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS)22,23, and soil pH was assessed using a glass electrode in a 1:1 soil-to-water suspension22. These procedures follow widely adopted protocols in soil science, allowing comparability with previous ecological and agronomic research.

Other potentially relevant ecological drivers, such as soil moisture and anthropogenic disturbance (e.g., land-use intensity, proximity to croplands or roads), were not included because consistent and comparable measurements across all plots were not feasible within the scope of this study. We acknowledge that these factors are important determinants of invasion dynamics, particularly in floodplain ecosystems where hydrology and disturbance strongly shape species establishment5,24. Their omission may contribute to residual variability in plant density, and we recommend their integration in future spatio-temporal monitoring frameworks.

Bayesian count models

To explore the relationship between M. pigra density and soil physicochemical properties, we employed Bayesian generalized linear models (GLMs) tailored for count data. In particular, we compared two widely used formulations: the Poisson and the negative binomial (NB) regression models. Both models utilize a log-link function, allowing for multiplicative effects of covariates on the expected count scale while ensuring non-negative predictions.

Let \(Y_i\) denote the observed count of M. pigra individuals in plot i, and let \(\varvec{x}_i\) represent the vector of covariates corresponding to soil properties and plant characteristics at that plot. The models were specified as follows:

-

Poisson model: \(Y_i \sim \text {Poisson}(\lambda _i), \quad \log (\lambda _i) = \beta _0 + \displaystyle \sum _{j=1}^{p} \beta _j x_{ij}\)

-

Negative binomial model: \(Y_i \sim \text {NegBin}(\mu _i, \phi ), \quad \log (\mu _i) = \beta _0 + \displaystyle \sum _{j=1}^{p} \beta _j x_{ij}\)

The negative binomial model extends the Poisson by introducing a shape (dispersion) parameter \(\phi\), which allows the variance to exceed the mean–i.e., \(\text {Var}(Y_i) = \mu _i + \mu _i^2 / \phi\). This formulation is particularly advantageous when modeling overdispersed count data, a common feature in ecological applications25,26.

Adopting a Bayesian framework enables full propagation of uncertainty, incorporation of prior knowledge, and coherent estimation under complex hierarchical structures10,12. All models were fitted using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, and convergence was assessed via \(\hat{R}\) diagnostics and effective sample sizes. Posterior predictive checks and information criteria were used to evaluate model adequacy and guide model selection.

Covariates. The predictor variables included soil pH, OM, P, K, EC, average stem diameter, soil texture (categorical), and soil structure (categorical). Categorical variables were incorporated using dummy coding, with “Clay” and “Granular” set as the reference categories for texture and structure, respectively.

Bayesian estimation. All models were fitted using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) via the brms package in R27, which interfaces with Stan28. We employed weakly informative priors instead of non-informative priors to incorporate minimal domain knowledge while avoiding unrealistic parameter estimates. This approach balances prior neutrality with numerical stability, consistent with recommendations in Bayesian inference10,29,30. Weakly informative priors act as gentle regularizers, preventing implausible coefficient magnitudes and enhancing sampling efficiency without exerting strong prior influence.

Specifically, regression coefficients were assigned Normal(0, 10) priors, centered at zero to reflect prior uncertainty regarding effect direction. The model intercept used a Student-t(3, 0, 10) prior, providing heavier tails to accommodate potential outliers. For the dispersion parameter (\(\phi\)) in the negative binomial model, a Gamma(0.01, 0.01) prior was used to account for possible overdispersion. These prior settings are weakly informative yet theoretically justified for ecological and epidemiological count data10,29.

Each model was run with four chains of 4,000 iterations, including 1,000 warm-up samples. Convergence diagnostics (\(\hat{R}=1\); ESS > 3,000) indicate reliable and independent posterior draws, demonstrating stable and efficient sampling across all parameters.

Model evaluation. Predictive performance was evaluated using the Leave-One-Out Information Criterion (LOOIC), a robust metric for estimating out-of-sample predictive accuracy in Bayesian models31. In addition, posterior predictive checks were performed to assess how well each model replicated the distributional features of the observed data. The negative binomial model produced a lower LOOIC compared to the Poisson model, indicating superior predictive performance, particularly under conditions of overdispersion. Based on these evaluations, the negative binomial model was selected as the final model for inference and interpretation.

Rationale. Modeling the covariates through a log-linear function is firmly rooted in the generalized linear model (GLM) framework, enabling clear interpretation of multiplicative effects on plant density while ensuring computational efficiency32. The Bayesian paradigm further strengthens the inferential process by explicitly accounting for uncertainty and providing the flexibility necessary to capture complex ecological relationships33.

Permissions and ethical considerations

This study involved non-destructive ecological fieldwork conducted in open-access public lands within Maha Sarakham Province, northeastern Thailand. Local communities commonly shared abandoned or marginal areas as survey sites for non-exclusive use. These areas are not classified as private property or protected zones under Thai law. As such, no specific research permits or ethical approvals were required.

Prior to fieldwork, the research team informed local community representatives in Mueang, Kantharawichai, and Kosum Phisai districts to ensure transparency and community awareness. The study complied with all applicable local regulations and posed no harm to people, property, or ecosystems.

Analytic results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed for key soil physicochemical properties and plant characteristics across 50 field plots. The variables included soil pH, organic matter (OM, i.e., soil organic matter content), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), bulk density, stem diameter, plant height, and M. pigra density (plants per square meter). Table 2 summarizes the central tendency and variability of these variables.

The mean soil pH was slightly acidic (6.61), with moderate variability. Potassium levels ranged widely, with an average of 46.21 ppm, while phosphorus content was low across all sites. The mean plant density was 12.49 plants/m2, with counts ranging from 1.5 to 35.5, indicating substantial heterogeneity in local population densities. Biomass also exhibited high variability, suggesting differential growth performance among invaded sites.

These baseline statistics provided context for subsequent modeling and facilitated the identification of key predictors influencing the spread and establishment of M. pigra.

Results

This study aimed to model the density of M. pigra–measured as the number of plants per square meter–as a function of soil physicochemical properties and plant morphological traits. To appropriately model the discrete response variable and account for potential overdispersion, we adopted a Bayesian generalized linear modeling framework incorporating both Poisson and negative binomial regression models.

Table 3 summarizes the posterior estimates from the Poisson model. Predictors whose 95% credible intervals exclude zero were interpreted as having strong evidence of an effect–including soil, K, stem diameter, and several soil texture classes (Clay Loam, Sandy Clay, Sandy Clay Loam, Sandy Loam, and Silty Clay). Subangular soil structure also showed strong evidence of a negative association with plant density. By contrast, variables such as pH, OM, N, P, bulk density, and plant height showed no strong evidence of effect.

Posterior estimates from the negative binomial model are presented in Table 4. The results are broadly consistent with those of the Poisson model, though the 95% credible intervals are slightly wider, reflecting greater uncertainty due to overdispersion. Soil, K and stem diameter show high posterior probability of non-zero effects (credible intervals excluding zero), as do five soil texture categories (Clay Loam, Sandy Clay, Sandy Clay Loam, Sandy Loam, and Silty Clay). Subangular soil structure exhibits strong evidence of a negative association with M. pigra density. The large estimated dispersion parameter further confirms overdispersion in the data, justifying the use of the negative binomial model for reliable inference.

Model comparison

To assess model performance, we compared the Poisson and negative binomial models using the Leave-One-Out Information Criterion (LOOIC), a fully Bayesian metric of out-of-sample predictive accuracy. A lower LOOIC indicates a better trade-off between model fit and complexity. We also report Bayesian \(R^2\) as a measure of the posterior mean proportion of variance explained by each model (Tables 5 and 6).

The negative binomial model achieved a slightly lower LOOIC (311.0) compared with the Poisson model (311.9), indicating superior out-of-sample predictive performance and greater parsimony (p_loo = 21.5 vs. 24.9). Although the elpd_loo difference between models was modest (\(-0.4\), SE = 1.6), the inclusion of a dispersion parameter (\(\phi\)) in the negative binomial specification allows it to explicitly model overdispersion in count data, leading to more robust inference and improved predictive reliability, particularly at higher plant densities25,26,34. Diagnostic checks, including Monte Carlo standard errors (MCSE = 0.2) and Pareto-k estimates (all \(k < 0.7\)), confirmed the stability of the LOO-based model comparison and further supported the negative binomial model as the preferred specification.

While the Poisson model yielded a slightly higher Bayesian \(R^2\) (0.615 vs. 0.596), suggesting marginally greater variance explained, the negative binomial model demonstrated superior predictive accuracy and a more flexible fit to the observed data. Taken together, these findings support the negative binomial specification as the most appropriate model, offering a principled way to account for overdispersion while maintaining strong explanatory power.

Posterior effects

Posterior predictive checks (PPCs) were performed to assess the adequacy of the fitted models in reproducing the observed distribution of M. pigra density. Two diagnostic plots were generated for each model: a density overlay plot comparing the distribution of observed and predicted counts and a bar plot displaying the frequencies of specific count values.

As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, both the Poisson and negative binomial models broadly captured the overall shape of the observed data. The Poisson model adequately reflected the central tendency but underestimated the variability, particularly in the upper range of count values. In contrast, the negative binomial model demonstrated a closer fit across the entire distribution, including the tails, highlighting its greater flexibility in handling overdispersion. These graphical diagnostics further support the selection of the negative binomial model as the more appropriate choice for inference and prediction.

Prediction interval analysis

Further evaluation of predictive performance focused on the negative binomial model, which was identified as the best-fitting model based on LOOIC and posterior predictive diagnostics. To visualize model uncertainty and predictive adequacy, prediction interval plots were generated using posterior draws from the fitted model.

Figure 4 presents the standard 95% prediction interval plot, which displays the observed counts alongside the model’s posterior medians and 95% prediction intervals. The majority of observed values fall within these intervals, suggesting that the model adequately captures both central tendency and variability.

To aid interpretation, Fig. 5 displays the same prediction intervals sorted by observed counts. This arrangement facilitates the identification of systematic patterns in model fit across the observed range. Additionally, Fig. 6 highlights observations that fall outside the 95% intervals (i.e., model “misses”), using color coding to distinguish between covered and uncovered observations. These deviations may reflect unmodeled heterogeneity, structural noise, or the influence of outliers.

Together, these graphical summaries reinforce the adequacy of the negative binomial model in accounting for the dispersion structure and predictive uncertainty inherent in the count data.

Model performance and interpretation

Based on the LOOIC comparison, the negative binomial model was marginally preferred over the Poisson model due to its slightly lower LOOIC and its ability to explicitly account for overdispersion, which is common in count data. Convergence diagnostics, including \(\hat{R}\) values near 1 and adequate effective sample sizes, indicated reliable parameter estimation for both models.

The final predictive equation derived from the negative binomial (NB) model for the expected count of M. pigra per square meter is expressed as follows:

Notation:

-

Density denotes the expected number of M. pigra individuals per square meter.

-

\(K\) denotes the concentration of extractable potassium in the soil, expressed in parts per million (ppm).

-

\(\text {Diameter}\) refers to the mean stem diameter of M. pigra individuals within each sampling plot, measured in centimeters.

-

\(\text {Texture}_i\) represents binary indicator variables for soil texture categories, where “Clay” serves as the reference level.

-

\(\text {Structure}_j\) represents binary indicator variables for soil structural forms, with “Granular” specified as the reference category.

-

\(\beta _0\), \(\beta _1\), \(\beta _2\), \(\gamma _i\), and \(\delta _j\) correspond to the regression coefficients estimated under the negative binomial framework.

The estimated coefficients and their 95% credible intervals are summarized in Table 7. The results show that soil texture and stem diameter exert meaningful effects on the expected density of M. pigra, while the effect of potassium concentration appears weak. Coefficients for Texture Loam, Texture Silty Clay Loam, and Structure Angular did not have 95% credible intervals excluding zero and thus were omitted from this summary, though they remain in the full model specification.

It is noteworthy that the model’s shape (dispersion) parameter was estimated to be very large, indicating that while overdispersion exists, the mean-variance relationship approaches that of a Poisson distribution augmented by an additional variance component.

Discussion

Ecological significance of predictors

The present study emphasizes the ecological significance of key edaphic and morphological variables in shaping the local abundance of M. pigra. Among these, soil potassium concentration, stem diameter, and soil texture emerged as the most influential predictors. Elevated potassium, a macronutrient critical for root development, osmotic regulation, and enzymatic activity, was positively associated with M. pigra density. This finding aligns with broader invasion-ecology evidence demonstrating that nutrient enrichment increases ecosystem susceptibility to alien species establishment by enhancing growth and competitive dominance3,6. From a management perspective, areas characterized by elevated soil fertility may thus constitute priority sites for early detection and intervention.

In contrast, the negative relationship between stem diameter and density reflects a classic self-thinning process, whereby intraspecific competition restricts recruitment and survival at higher population densities35. This indicates that stem diameter may serve as a cost-effective field proxy for invasion stage or stand maturity, allowing managers to differentiate between expanding fronts and long-established populations when allocating control efforts.

Soil texture was also found to be a pivotal determinant of invasion risk. Plots with sandy and clay loam soils supported substantially higher M. pigra densities, likely owing to their favorable moisture retention and aeration properties that facilitate seed germination and early establishment5. Conversely, heavy clay soils were associated with reduced densities, suggesting that poor drainage and compaction may function as edaphic resistance mechanisms that restrict invasion success in certain microsites. These findings underscore the role of soil fertility and physical structure in mediating invasion dynamics by influencing resource availability, hydrological conditions, and competitive interactions. Understanding these ecological mechanisms not only advances knowledge of invasion processes but also provides a foundation for soil-based risk assessments and the development of targeted management strategies in vulnerable wetland ecosystems.

The influence of soil texture is closely linked to site hydrology, particularly in floodplain environments. Sandy clay and clay loam soils, which balance water retention and aeration, create conditions conducive to M. pigra seed germination and seedling survival. In contrast, heavy clay soils with poor drainage may create anaerobic conditions that hinder establishment, acting as natural resistance zones. These findings align with previous research demonstrating that interactions between soil structure and hydrology function as critical ecological filters for invasive plant success.

Methodological implications

The negative binomial model was a better fit for the data than the Poisson model. It more accurately accounted for the overdispersion and the wide range of M. pigra densities. While the difference in LOOIC values was small, the negative binomial model’s inclusion of a dispersion parameter makes it a more robust and broadly applicable tool for ecological forecasting. These findings align with previous research showing that even slight improvements in predictive accuracy can offer significant advantages for ecological management and decision-making24,26,34,36.

A key contribution of this study lies in applying a Bayesian modeling framework to invasion ecology. Unlike traditional frequentist approaches, which typically rely on maximum likelihood estimates and may underestimate uncertainty in overdispersed datasets26, Bayesian methods propagate full posterior uncertainty, integrate prior knowledge, and allow retention of ecologically relevant predictors even when statistical support is weak10. This flexibility results in more stable inference and avoids premature variable exclusion. In addition, Bayesian models provide a unified platform for incorporating hierarchical structures, zero inflation, and spatiotemporal dynamics–features that are essential for understanding invasion processes but often challenging to address with conventional methods33,37. Posterior predictive checks, LOOIC-based model comparison, and effective sample size (ESS) diagnostics offer richer and more robust evaluations than likelihood ratio tests or AIC commonly applied in frequentist analyses31.

This study emphasizes that incorporating anthropogenic disturbances is crucial for enhancing the predictive accuracy of future invasion models. Large-scale soil displacement from activities such as road construction and land development creates new niche spaces and alters soil environments, thereby providing opportunities for seed germination and seedling establishment that facilitate the spread of invasive species like M. pigra. Therefore, extending Bayesian modeling frameworks to explicitly capture these land-use dynamics could significantly improve the utility of ecological forecasts for landscape-scale management.

Study limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the ecological drivers of M. pigra invasion, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the dataset comprises only 50 plots collected from a single province during a limited time frame, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings across broader spatial or temporal contexts. Seasonal dynamics, including variation in precipitation and flooding, were not explicitly incorporated and could influence both soil properties and plant densities.

Second, the study area is restricted to Maha Sarakham Province, whose soils are characterized by slightly acidic pH (\(\sim 6.5\)), low potassium availability, and clay to clay-loam textures typical of floodplain environments in the Lower Mekong Basin. While these edaphic conditions are broadly representative of many invaded wetlands in mainland Southeast Asia, they may not capture the full range of soil heterogeneity across the species’ invaded range. Consequently, extrapolation of our findings should be undertaken with caution.

Third, important ecological and anthropogenic variables–such as land-use history, disturbance regimes, proximity to water bodies, and competition with native flora–were not included in the current models. Their omission may contribute to unexplained variability in plant density.

Finally, although Bayesian models enable robust inference with relatively limited data, the high number of covariates relative to sample size may still pose risks of overfitting. Future research should therefore adopt longitudinal sampling across multiple seasons and extend coverage to other regions to enhance both model robustness and transferability.

Broader applications and future research

The findings offer practical insights for risk-based monitoring and habitat prioritization. Areas characterized by potassium-rich, sandy, or clay loam soils may be especially vulnerable to M. pigra invasion and should be prioritized for early detection, containment, and restoration. The strong predictive performance of the negative binomial model also suggests its utility in other contexts involving overdispersed count data.

To scale up these results, future studies should integrate this modeling framework with spatially explicit environmental data such as remote-sensed soil moisture, flood frequency, or land use classification derived from satellite imagery. Such integration could improve landscape-level forecasting of invasion risk and inform regional management strategies.

Additionally, incorporating climatic variables (e.g., seasonal precipitation or temperature anomalies) and hydrological metrics (e.g., flood duration or water table depth) could refine predictions of invasion dynamics under shifting environmental conditions. Hierarchical Bayesian models could also be used to partition variation across spatial or administrative units (e.g., sub-districts), while spatiotemporal Bayesian approaches may help identify emerging invasion fronts or lagged ecological responses38.

For example, a future extension of this study could combine plot-level count data with high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery and hydrological modeling to predict M. pigra expansion along riparian corridors in the Chi River Basin. This approach would allow for dynamic invasion risk maps and adaptive monitoring protocols.

In the context of global change, such forecasting frameworks are increasingly valuable. Climate variability, land-use change, and intensifying human disturbance are expected to accelerate the spread of invasive species in many tropical and subtropical regions3. Robust, data-driven models such as those developed in this study can play a central role in guiding proactive, spatially targeted management of biological invasions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of Bayesian count models–particularly the negative binomial model–in predicting the local density of M. pigra based on soil physicochemical properties. Among the predictors examined, potassium concentration, stem diameter, soil texture, and soil structure were identified as key ecological drivers influencing invasion dynamics. By directly addressing overdispersion and incorporating uncertainty, the Bayesian framework strengthens both inferential validity and predictive performance.

The results offer a robust scientific foundation for developing spatially targeted management strategies, particularly in areas with soil conditions conducive to M. pigra establishment. The integration of statistical modeling with ecological insight supports more informed, evidence-based approaches to invasive species risk assessment and intervention planning.

To improve predictive capacity and practical applicability, future research should expand this modeling framework to include climatic, hydrological, and anthropogenic factors. Incorporating spatiotemporal Bayesian approaches will further enhance model scalability and forecasting precision, thereby advancing the use of predictive ecological modeling in both regional management efforts and broader environmental policy development.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study includes field survey data on M. pigra density and associated soil properties collected from northeastern Thailand. Due to institutional data protection policies, the data are not publicly available. However, the corresponding author can make the dataset available upon reasonable request.

References

Pimentel, D., Zuniga, R. & Morrison, D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 52, 273–288 (2005).

Richardson, D. M. & Rejmánek, M. Trees and shrubs as invasive alien species - a global review. Divers. Distrib. 17, 788–809 (2011).

Essl, F. et al. Drivers, impacts, and management of future biological invasions under global change. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5–23 (2023).

Richardson, D. M. et al. Naturalization and invasion of alien plants: concepts and definitions. Divers. Distrib. 6, 93–107 (2000).

Nawaz, M. F., Bourri’e, G. & Trolard, F. Soil compaction impact and modeling: a review. Agronomy 10, 879 (2020).

Seabloom, E. W. et al. Plant species’ origin predicts dominance and response to nutrient enrichment and herbivores in global grasslands. Nat. Commun. 6, 7710 (2015).

Douglas, M. M., O’Connor, R. A. & Evans, R. M. The impact of the invasive weed Mimosa pigra on wetland wildlife in northern Australia. Wildl. Res. 25, 623–638 (1998).

Walden, D., Lonsdale, W. M. & Farrell, G. A risk assessment of the tropical wetland weed Mimosa pigra in northern Australia. Supervising Scientist Report 177 (Supervising Scientist, Darwin, Australia, 2004).

Paynter, Q. & Flanagan, G. J. Integrated management of Mimosa pigra: use of biological control and fire. Weed Technol. 18, 138–146 (2004).

Gelman, A. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis 3rd edn. (CRC Press, 2014).

Hooten, M. B., Johnson, D. S., McClintock, B. T. & Morales, J. M. Bringing Bayesian models to life. Ecol. Monogr. 90, e01429 (2020).

Green, E. J., Finley, A. O. & Strawderman, W. E. Introduction to Bayesian Methods in Ecology and Natural Resources (Springer, 2020).

Lonsdale, W. M. The biology of Mimosa pigra L. In K. L. S. Harley (Ed.), A Guide to the Management of Mimosa pigra (pp. 8–32) (CSIRO, Canberra, 1992).

Lonsdale, W. M. Rates of spread of an invading species: Mimosa pigra in northern Australia. J. Ecol. 81, 513–521 (1993).

Grice, A. C. Weed management in rangelands: mimosa and beyond. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 44, 993–999 (2004).

Thai Meteorological Department. Climate statistics of Thailand: annual temperature and precipitation. Preprint at https://www.tmd.go.th/ (2023).

Department of Mineral Resources. Geological and mineral resource zoning for land management in Maha Sarakham Province (Department of Mineral Resources, 2009).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System, version 3.40. Open Source Geospatial Foundation. Retrieved from http://qgis.org (2024).

Walkley, A. J. & Black, I. A. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37, 29–38 (1934).

Soil Survey Division Staff. Soil Survey Manual. USDA Handbook No. 18 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 2017).

Bray, R. H. & Kurtz, L. T. Determination of total, organic, and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Sci. 59, 39–45 (1945).

Jackson, M. L. Soil Chemical Analysis (Prentice Hall, 1965).

Sparks, D. L. et al. Methods of Soil Analysis – Part 3: Chemical Methods (Soil Science Society of America, 1996).

Wenger, S. J. & Olden, J. D. Assessing transferability of ecological models: an underappreciated aspect of statistical validation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 260–267 (2012).

O’Hara, R. B. & Kotze, D. J. Do not log-transform count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 118–122 (2010).

Hilbe, J. M. Negative Binomial Regression, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Bürkner, P.-C. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Carpenter, B. et al. Stan: a probabilistic programming language. J. Stat. Softw. 76, 1–32 (2017).

Gelman, A., Simpson, D. & Betancourt, M. The prior can often only be understood in the context of the likelihood. Entropy 19, 555 (2017).

McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan. 2nd edn. (CRC Press, 2020).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27, 1413–1432 (2017).

McCullagh, P. Nelder, J. A. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1989).

Clark, J. S. Why environmental scientists are becoming Bayesians. Ecol. Lett. 8, 2–14 (2005).

Warton, D. I., Lyons, M., Stoklosa, J. & Ives, A. R. Three points to consider when choosing a model for non-normal data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 646–653 (2016).

Pretzsch, H., Biber, P. & Uhl, E. Size–density relationships in mixed-species stands indicate density-dependent growth dynamics. Ecol. Appl. 30, e02108 (2020).

Thorson, J. T., Ianelli, J. N. & Shelton, A. O. Meta-analysis of life history data suggests models for vital rates are robust to data gaps. Ecol. Appl. 26, 701–713 (2016).

Cressie, N. & Wikle, C. K. Statistics for Spatio-Temporal Data (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

K’ery, M. & Royle, J. A. Applied Hierarchical Modeling in Ecology: Analysis of Distribution, Abundance and Species Richness in R and BUGS (Academic Press, 2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of field and laboratory personnel in data collection and analysis. This research project was financially supported by Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bhuvadol Gomontean and Khemmanant Khamthong jointly conceived the study and developed the methodological design. Both authors carried out fieldwork, curated the dataset, performed statistical analyses, and interpreted the results. Aljo Clair Pingal contributed to statistical validation and refinement of the Bayesian models. All authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. Khemmanant Khamthong supervised the project, provided administrative coordination, and secured research funding. Bhuvadol Gomontean and Khemmanant Khamthong contributed equally to this work. Khemmanant Khamthong is the corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomontean, B., Pingal, A.C. & Khamthong, K. Modeling invasion risk of Mimosa pigra L. in Northeastern Thailand using Bayesian count models. Sci Rep 15, 40156 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23826-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23826-x