Abstract

In contemporary performance education, the Animal Exercise course is one of the core training modules for developing imitative behavior. Typically, instructors facilitate this process through guided demonstrations and task-based instruction, encouraging students to engage in both imitation and creative exploration. The pedagogical approach is therefore characterized by active student participation and a strong emphasis on experiential, practice-oriented learning. However, assessment in Animal Exercise courses still relies primarily on instructors’ subjective judgment, resulting in inconsistent and non-standardized evaluations. This hinders students’ ability to identify skill deficiencies and improve their course performance. To address this challenge, we propose a quantitative framework for evaluating imitative behavior using pose estimation, termed Human Pose Estimation–Imitative Behavior Analysis (HPE-IBA). Using this framework, we employ a standard RGB camera to collect motion data from both students and gorillas, extract three-dimensional joint coordinates, and compute dynamic joint angles with MediaPipe. We then apply correlation analysis to identify weakly correlated features and core joints, followed by two-way ANOVA to examine the effects of training status and gender on students’ imitation performance. Analysis of chest-beating and walking imitation reveals a statistically significant interaction between training status and gender (p< 0.01), primarily reflected in joint patterns such as the right elbow and right knee. The proposed framework not only enhances the application of pose estimation in acting education but also provides a foundation for broader applications in performance-based motion analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imitative behavior is the cornerstone of acting education, contributing to the enhancement of students’ physical expressiveness and role construction abilities1. Among the influential methodologies, Animal Exercise, introduced by Stanislavski, serves as a key approach for training students in imitative behavior. He posited that by imitating the characteristic movements of animals, such as crawling, foraging, chest-beating, and scratching, students could strengthen their physical expressiveness and deepen their understanding and embodiment of roles2. In current pedagogical practice, instructors typically assume the role of demonstrators and facilitators, designing diverse imitation tasks to stimulate students’ bodily awareness and imagination. Through repetitive practice, peer feedback, and individual creativity, students gradually acquire the bodily control and expressive skills essential for performance. Today, Animal Exercise has been formalized as an independent course within performance curricula, aimed at enhancing students’ proprioception and bodily control. Although the curriculum is widely used in developing performance skills, the lack of quantitative, targeted analytical tools restricts the optimization of personalized training strategies, especially when considering the multifaceted impacts of gender and training status on imitation accuracy. The fundamental issue lies in the lack of in-depth study of the interrelationships among joints during the process of mimicking animal behaviors. At the same time, teaching evaluations in acting education suffer from fundamental shortcomings: the evaluation process overly relies on teachers’ subjective experiences and observations, leading to divergent guiding philosophies among different teachers, while the same teacher often adopts a uniform teaching method for different students, thereby making it difficult to accurately reflect individual differences and true performance levels3.

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision has transformed motion analysis methods4. With the aid of deep learning, human pose estimation technology has achieved real-time modeling of the movements of various body parts, providing strong support for motion analysis and behavioral assessment.5,6. For example, MediaPipe captures dynamic changes in key joints such as the shoulders, elbows, knees, and hips by tracking 33 key points in real time. This enables precise extraction and quantitative analysis of motion features, providing data support for evaluating movement accuracy, rhythm, and coordination 7,8. Although MediaPipe has been widely applied in motion tracking9, its potential in performing arts education has yet to be fully explored.

This study first collected motion data from gorillas and recorded videos of students imitating gorilla behaviors. Subsequently, MediaPipe technology was employed to extract three-dimensional joint coordinates and compute dynamic joint angles. To effectively utilize these data, a correlation analysis was conducted on the motion data of both gorillas and students, and core joints were selected as the primary experimental targets based on the results. Finally, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the core joint data to examine the effects of training status and gender on imitation behavior10. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

This study presents an analytical framework for the quantitative assessment of human imitation of animal behaviors. The framework supports analysis of students’ imitation of gorilla chest-beating and walking actions and demonstrates potential for broader application in other movement scenarios.

-

This study is the first to apply correlation analysis to animal exercise courses, identifying significant independence in joint angle changes in the chest-beating and walking data of gorillas and students. This finding provides a theoretical basis for further identification of core joints and offers important support for the scientific validity of quantitative assessments.

-

To examine the effects of gender and training status on imitative behavior, this study introduces a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. The model reveals the combined effects of gender and training status on the elbow and knee joints, providing valuable insights for targeted teaching optimization.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Chapter 2 provides a review of human pose estimation technology and its applications in motion analysis, with a focus on the current state of related research in performing arts education. Chapter 3 introduces the application of MediaPipe technology in this study and describes the experimental design, including participant information, action selection and standardization, as well as data collection and processing procedures. Chapter 4 validates whether joint angles can be analyzed independently, laying a theoretical foundation for subsequent studies. Chapter 5 applies a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyze the experimental results in depth, discussing the combined effects of gender and training status on imitative behaviors and providing targeted teaching feedback suggestions. Chapter 6 summarizes the research findings, discusses the limitations of the study based on the experimental results, and outlines future research directions.

Related work

This chapter reviews key areas of related research, laying the theoretical foundation for addressing the unique challenges of imitative behavior assessment in acting education.

Correlation analysis in motion analysis

Correlation analysis is a fundamental statistical method for quantifying associations between variables and plays a crucial role in motion analysis research11,12. In this domain, Pearson correlation is commonly used to measure the linear relationship between joint angles or body segments during pose sequences. For example, Fagerberg et al.13 examined temporal correlations between upper and lower limb joints (e.g., shoulders and knees) to understand motion coordination in full-body gestures. Their system extracted angular data from motion capture files and computed correlation matrices to evaluate inter-joint dependencies in complex actions.

In studies focusing on imitative behavior, researchers often use joint-wise correlation analysis to compare a subject’s movement trajectory with that of a target model. For instance, Demšar et al.14 computed correlations between animal and human joint trajectories using 3D pose vectors to evaluate motion similarity. This method facilitates the detection of synchronized or mismatched segments in imitation tasks.

Additionally, correlation analysis has been used to assess how training or fatigue affects joint dynamics. For example, time-series data across multiple trials can be segmented into windows and analyzed for intra-subject consistency using sliding-window correlation or dynamic time warping. Lan et al.15 also applied sensor-based motion capture and cross-sensor correlation verification to evaluate hardware consistency and data reliability, thereby helping to validate experimental conditions.

It is important to note that low Pearson correlation coefficients (e.g., below 0.4) do not imply biomechanical independence in a strict physiological sense. Joint interdependencies may be nonlinear and influenced by task-specific neuromuscular constraints. In this study, correlation analysis was employed as an exploratory approach to identify relatively decoupled joint pairs, serving as a heuristic to simplify modeling and highlight candidate joints for further analysis.

These studies highlight how correlation analysis can reveal latent patterns in movement coordination, motion similarity, and even systemic noise, thereby supporting research in physical therapy, dance science, and acting education.

Applications of human pose estimation in motion analysis

Recent advances in human pose estimation (HPE) have provided efficient tools for extracting detailed biomechanical data from video or depth sensors. Among these, MediaPipe Pose has gained popularity for its real-time performance and deployment simplicity. The system employs the BlazePose architecture, which combines a lightweight CNN detector and a landmark regression network to predict 33 human keypoints in 2D and 3D from RGB images. It supports frame rates up to 30–50 FPS on mobile or desktop platforms without GPUs.

Mitrovic et al.16 used MediaPipe to extract real-time joint angles in athletic performance videos. They computed angles between vectors formed by keypoints (e.g., shoulder–elbow–wrist), applied smoothing filters to reduce jitter, and conducted temporal analysis of movement phases. Similarly, Kim et al.17 quantified lower-body joint trajectories for rehabilitation exercises, using statistical thresholds to detect anomalies in knee and ankle motion. Their methodology involved synchronizing pose sequences with ground-truth data collected from wearable IMUs to validate accuracy.

WuBo et al.18 applied MediaPipe to a driving simulation study, where ankle flexion–extension angles were measured during acceleration and braking events. Their system processed 2D keypoints extracted from dashboard video feeds, with angle computation and event labeling synchronized via time stamps. The study demonstrated that small deviations in ankle angle dynamics could correlate with delayed reaction time and reduced control precision.

Moreover, MediaPipe has been widely adopted due to its real-time processing capabilities, lightweight architecture, and cross-platform availability. Compared with OpenPose and AlphaPose, MediaPipe is more suitable for resource-constrained environments where low latency is essential, making it a more efficient solution for teaching scenarios in performance education19.

Despite these successes in motion-heavy contexts, most HPE applications remain focused on sports or driving scenarios. Their potential in performance education, particularly in analyzing expressive and symbolic movement such as animal imitation, remains largely untapped.

Animal exercise courses and imitative behavior studies in acting education

In acting pedagogy, animal exercise courses are rooted in the Stanislavski system and are widely employed to enhance physicality, embodiment, and non-verbal expressiveness20. These exercises encourage students to mimic animal movements, such as crawling, climbing, chest-beating, and scratching, thereby developing kinesthetic awareness and emotional range21.

Most evaluations in such courses are qualitative and subjective, relying on instructors’ observation of student expressiveness and engagement. However, Gonzalez-Badillo et al.22 explored the use of joint angle tracking to assess motion proficiency in performance training. Their system used Kinect v2 sensors to extract skeletal data and compute joint angles over time to identify motor inefficiencies. They proposed a rule-based scoring system that evaluates joint flexibility and timing alignment of student actions with instructor models.

Despite these advancements, such methods remain underutilized in contexts involving imitative movement, particularly in theater and acting education. Fujisaki et al.23 emphasized the psychological and motivational value of animal exercises but did not provide methods for analyzing physical performance components such as spatial precision, movement symmetry, or velocity patterns.

In addition, most existing studies fail to consider multivariate factors such as gender, prior training experience, or the complexity of the target movement. This limitation reduces the effectiveness of delivering personalized feedback or adapting curricula to meet the needs of diverse learners. Our approach extends prior work by introducing human pose estimation-based metrics, capturing joint angles from camera feeds and enabling intersubject comparisons across multiple variables.

By utilizing 3D pose data (for example, from MediaPipe), it is possible to segment dynamic actions such as climbing and walking, compute joint-specific deviations between student and expert trajectories, and model individual progression. This enables instructors to move beyond binary pass/fail grading and to provide continuous, quantitative feedback during training.

Artificial intelligence in acting education: enhancing evaluation and feedback

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies into education has introduced automated movement evaluation systems capable of delivering real-time feedback. Bi Chunyan et al.24 conducted a comprehensive review of deep learning models for movement classification. They highlighted convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained on human pose sequences extracted using tools such as OpenPose or MediaPipe. These models achieved high accuracy in tasks such as action recognition, posture detection, and feedback generation, enabling real-time comparison between learner and reference motion templates.

Zhou Nan et al.25 developed a multimodal classroom behavior analysis platform that combined pose estimation with facial emotion recognition, using ResNet50 and LSTM-based time-series models. Their system aggregated behavioral cues (such as slouching, eye contact, and hand raising) into an engagement score that was updated in real time. This allowed teachers to identify disengaged students and adapt content delivery accordingly.

While these systems demonstrate the feasibility of AI-assisted teaching, they are primarily designed for static classroom scenarios and lack support for highly variable, expressive tasks such as acting or dance. Moreover, they often overlook symbolic or stylized movement forms, including animal imitation and exaggerated emotional gestures.

Our proposed framework builds upon these foundations by applying AI to the quantitative evaluation of imitative behavior, integrating time-synchronized pose analysis, intersubject comparison, and multidimensional factor modeling. This represents a novel application of AI in performance education and a step toward automated, personalized coaching systems in the expressive arts.

Methodology

To address the challenges of quantifying imitative behaviors in acting education, we propose a novel framework named Human Pose Estimation-Imitative Behavior Analysis (HPE-IBA). This framework integrates advanced pose estimation techniques with correlation analysis and two-way ANOVA to enable data-driven analysis and joint-level feedback, thereby supporting the optimization of teaching strategies. The following sections detail the methodology and experimental setup of the HPE-IBA framework.

Human pose estimation-imitative behavior analysis framework

The HPE-IBA framework consists of three core stages: data acquisition, motion feature quantification, and statistical analysis. Each stage is designed to transform raw motion data into actionable insights for personalized instructional feedback, utilizing human pose estimation and rigorous statistical analysis. The overall workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the details of each stage are described below.

Data collection and preprocessing

The experimental protocol was approved by the Department of Drama and Film Arts at Xingtai College. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Participants’ names and other identifying information were removed from all text, images, and videos, and written informed consent was additionally obtained for the publication of any images or videos.

A total of 10 acting students participated in the study, consisting of 5 trained (second-year) and 5 untrained (first-year) students, with an equal gender balance (5 males and 5 females). Participants’ heights ranged from 160 cm to 183 cm. The characteristics of training status, gender, and height were explicitly considered in the data analysis. In particular, joint coordinate normalization was performed using limb-length ratios (e.g., shoulder–wrist, hip–ankle) to minimize variability due to body size. Furthermore, training status and gender were used as grouping variables in the subsequent two-way ANOVA to examine their effects on imitation performance. Detailed participant information is shown in Table 1.

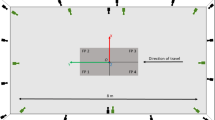

We first collected standardized video recordings of gorilla chest-beating and walking behaviors, along with synchronized recordings of students’ imitation performances during acting classes. Recordings took place in an indoor performance studio measuring approximately 8 \(\times\) 10 meters, equipped with adjustable overhead lighting to ensure uniform illumination. A full black blackout curtain was hung in the background to minimize environmental interference and enhance the accuracy of pose extraction. For hardware implementation, we employed a camera capable of capturing 1920 \(\times\) 1080 RGB resolution and 1280 \(\times\) 720 depth resolution at 60 frames per second.

Using the MediaPipe Pose module, we then extracted 33 three-dimensional key points from each frame. The raw data subsequently underwent rigorous cleaning and standardization to ensure accuracy and consistency in the subsequent analyses.

Motion feature quantification

To minimize students’ deliberate focus on specific actions, this experiment was conducted as part of an Animal Exercise course without disclosing its true purpose to participants. Each student watched 8 short video clips (approximately 5 seconds each) of gorilla chest-beating and walking behaviors. After a 10-minute observation period, students were asked to imitate the actions freely in an acting classroom equipped with a fixed camera. No instruction or correction was provided during the imitation process to preserve the natural expressiveness of movement. The resulting videos captured diverse and creative interpretations, providing a rich basis for motion analysis.

This study utilized MediaPipe to extract the three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates of body joints. Based on these coordinates, joint angles were computed by modeling adjacent limb segments as vectors. Specifically, the joint angle \(\theta\) was calculated using the arccosine of the dot product of two adjacent vectors, normalized by the product of their magnitudes, as shown in Equation 1:

Here, \(\textbf{u} = (u_x, u_y, u_z)\) and \(\textbf{v} = (v_x, v_y, v_z)\) represent vectors formed by two adjacent bones. for example, from the shoulder to the elbow and from the elbow to the wrist, respectively.

To quantify dynamic changes in movement, we further computed angular variation between two selected frames using Equation 2:

where \(\theta _1\) and \(\theta _2\) are the joint angles at two consecutive or reference frames, and \(\theta _c\) denotes the magnitude of angular change between them.

Normalization and limb proportion correction were applied using limb-length ratios (e.g., shoulder–wrist, hip–ankle) to reduce inter individual variability. These features served as the basis for statistical modeling and performance evaluation.

Interaction effects and analysis

The independence of joint movements is assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient matrices, with heatmaps visualizing the coordination patterns of symmetric and asymmetric joints. Furthermore, two-way ANOVA is employed to investigate the interaction effects of gender and experience on imitation accuracy.

Based on the statistical results, the core joints with the greatest impact on imitation accuracy are identified, and recommendations for optimizing teaching strategies are provided. The entire workflow transforms the motion information extracted from the video data into scientifically quantified feedback on imitative behavior in performing arts education, thereby providing data support for the formulation of personalized teaching strategies.

MediaPipe-based human pose estimation and data standardization

In this study, we focused on two continuous, non-discrete imitation behaviors: gorilla chest-beating and gorilla walking. These actions lack fixed initiation and termination points, making standardization essential for meaningful pose-based comparison. To address this, we defined a structured segmentation protocol for each motion type.

To prevent students from deliberately mimicking the gorilla’s motion patterns, they were allowed to perform chest-beating and walking actions freely, without restrictions on specific movement forms or execution duration. These performances were recorded on video and then precisely edited to extract complete pose sequences.

For the gorilla chest-beating action, segmentation was based on two alternating postures. The first posture was identified when the left hand was raised while the right hand struck the chest, and the second when this configuration was reversed. Similarly, for the gorilla walking action, the first frame was defined as the moment when the left foot was lifted and stepped forward while the right foot remained grounded, and vice versa for the second.

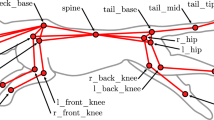

The selection of these key frames was not based on manual visual judgment but was instead derived from an analysis of joint angle trajectories extracted by MediaPipe. Specifically, we examined frame-by-frame variations in joint angles and identified key moments corresponding to local extrema or inflection points–such as limb elevation or impact. This rule-based segmentation ensured consistency across participants and minimized observer bias. The relevant joint angles were computed across all frames in each motion sequence. This process is visualized in Fig. 2, and the annotated joint angles are shown in Fig. 3.

To preserve naturalness and avoid priming effects, students were instructed to perform the actions without constraints on form or timing. The videos were then carefully trimmed to extract only the relevant motion cycles for analysis. This protocol ensured that the resulting pose sequences were consistent, comparable, and free from imitation bias, thereby enabling accurate assessment of joint-based imitation performance.

Ethics approval.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Drama and Film Arts at Xingtai College (No.2024002) and was conducted in accordance with relevant national and institutional ethical guidelines.

Consent to participate.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. All individuals whose images appear in this manuscript have agreed to the publication of these images.

Joint independence verification

Typically, the execution of movements is not achieved through the independent action of a single joint. Both gorilla movements and students’ imitations inevitably involve coordination among multiple joints. For example, during walking, leg movements are often accompanied by arm swings. As a result, teachers can only evaluate the similarity in students’ movements, without providing more precise guidance on the core joints involved in the actions. Moreover, due to variations in datasets, each analysis of imitative movements may involve different joints, posing a challenge for teachers to provide objective and quantifiable analysis methods. To address this issue, this study seeks to verify whether there is independence between joints during the movement execution.

To explore inter-joint coordination patterns, we conducted a correlation analysis based on joint angle data extracted from gorilla and student motion recordings.

Correlation analysis

We used MediaPipe to collect joint motion data from both gorillas and students performing chest-beating and walking actions. Prior to conducting factor analysis on imitative movements, we performed a correlation analysis on joint angle data to assess the degree of synergy among joints and to identify the most representative joints for subsequent investigation. The data included key joints such as the left and right shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and ankles.

In this study, we used the Pearson correlation coefficient to analyze the linear relationships between joint angles. According to Gogtay and Thatte26, the Pearson coefficient (r) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables, where +1 indicates perfect positive correlation, -1 indicates perfect negative correlation, and 0 indicates no linear correlation. Based on the principles of correlation analysis and empirical thresholds proposed by Cohen27 and Mukaka28, an absolute correlation coefficient below 0.4 is generally considered to reflect a lack of meaningful linear association. In this study, joint pairs with \(|r|<0.4\) were regarded as weakly correlated and assumed to exhibit low coordination during movement.

Based on the correlation heatmap in Fig. 4, it can be observed that the knee and hip joints of the gorilla and student exhibit significant independence during the walking motion. First, consider the left side of the Correlation Heatmap of Gorilla Walking Joint Angles. For shoulder movements, the correlation between the left shoulder and right shoulder is 0.33, indicating a certain degree of synchrony during walking, but this synchrony is relatively weak. For lower limb movements, the correlation between the left hip and right hip reaches 0.82, demonstrating a high level of coordination in the hip joints during gorilla walking, which plays a critical role in maintaining gait stability. For the knees, the correlation between the left knee and right knee is 0.81, reflecting a high level of synchrony in knee movements during gorilla walking. Additionally, the analysis of ankle joints shows that the correlation between the left ankle and right ankle is only 0.13, indicating a high degree of independence in ankle movement patterns. This may be related to the gorilla’s unique walking style and the role of the ankle in maintaining stability.

Next, consider the Correlation Heatmap of Student Walking Joint Angles on the right. The analysis of joint angle variations during walking reveals that the correlation between the left and right shoulders is 0.08, indicating a high degree of independence in shoulder movements. In contrast, the correlation between the left and right hips is 0.79, demonstrating a high level of coordination in the hip joints during walking. This suggests that the coordination of the hip joints plays a crucial role in maintaining walking stability. Additionally, the correlation between the left and right knees is 0.67, reflecting strong coordination between the knees, which is important for maintaining gait balance. Furthermore, the analysis of the ankle joints shows a correlation of 0.44 between the left and right ankles. This lower correlation, compared to that of the gorilla, may be attributed to differences in gait patterns and the varying demands for foot stability.

As shown in Fig. 5 , in the correlation matrix analysis of the gorilla chest-beating motion, we observed the coordination and independence features between different joints. First, the correlation between the left and right shoulders is as high as 0.93, indicating that the shoulder movements are highly synchronized during the chest-beating action. In contrast, the correlation between the shoulder and elbow joints is relatively low, with the left shoulder and left elbow correlating at 0.13, and the right shoulder and right elbow showing a correlation of -0.03. This suggests relatively independent movements with weak coordination between the two joints. The elbow joints exhibit moderate coordination, as indicated by a correlation of 0.53 between the left and right elbows. This indicates a certain degree of synchronization between the elbows, but it is not as strong as the shoulder coordination. The correlation between the hip joints is 0.81, indicating strong synchronization, which is crucial for maintaining body stability during the movement. However, the correlation between the hips and elbows is low, further suggesting that the upper and lower limbs exhibit independent movements during this action. A correlation of 0.67 between the knee joints reflects moderate coordination between the left and right knees. Although this coordination is weaker than the hips, it still indicates a certain level of synchronization. The correlation between the knees and shoulders is low, implying that the knee movements are not directly influenced by the shoulder actions. Finally, the ankle joints exhibit a very low correlation of 0.03 between the left and right ankles. This indicates almost no synchronization between the ankles, suggesting that the ankle joints play a role primarily in providing support and stability, rather than coordinating with the upper limb movements.

In the correlation heatmap analysis of the students’ chest-beating motion, we observed the characteristics of coordination and independence between different joints. First, the shoulder joints showed a low correlation, with a correlation of only 0.22 between the left and right shoulders, indicating a certain degree of independence in the movement of the shoulder joints. The correlations between the shoulders and their respective elbows were also relatively low, further emphasizing the independence of the upper limbs during the chest-beating action. Next, the elbow joints exhibited weak coordination between the left and right sides, with a correlation of 0.20 between the left and right elbows. This was the highest correlation value observed between the elbow joints, suggesting that the elbow movements are more dependent on the independent motion of the arms. In contrast, coordination in the lower limbs was more pronounced. The correlation between the left and right hips was 0.87, indicating that the hip movements during chest-beating are nearly synchronized, which helps maintain body stability and balance. The correlation between the left and right knees was 0.48, suggesting that while there is some coordination in knee movements, it is not fully synchronized. The correlation between the left and right ankles was 0.56, showing relatively higher synchronization, which contributes to maintaining a stable standing posture.

Core joint identification

In this study, we analyzed the coordination and independence between different joints during the gorilla chest-beating motion. The correlation heatmaps in Fig. 5a reveal clear differentiation between symmetric and asymmetric joint pairs. It was observed that symmetric joints, such as the left and right shoulders, exhibited high correlation values, with the left and right shoulders having a correlation of 0.93. This indicates a high degree of synchronization in the movement of symmetric joints during the chest-beating action. On the other hand, asymmetric joints, such as the shoulder and elbow, displayed relatively low correlation values, suggesting a greater degree of independence in their movement. For instance, the left shoulder and left elbow had a correlation of only 0.13, and the right shoulder and right elbow showed a near-zero correlation of -0.03. These findings underscore the fact that symmetric joints tend to move in close coordination, whereas asymmetric joints operate more independently. The low correlation values between asymmetric joints, such as the shoulder-elbow and knee-ankle pairs, further reinforce this distinction. The analysis provides valuable insights into the biomechanics of complex motion, highlighting the critical role of joint coordination in maintaining both stability and motion efficiency.

Based on these findings, we found that during chest-beating or walking actions, the angles of core joints can be analyzed independently, and these angle changes are not significantly influenced by the movements of other body parts. In walking movements, as illustrated in Fig. 4, both students and the gorilla demonstrate that core joint coordination is predominantly exhibited by the hip and knee joints. However, during chest-beating movements, as shown in Fig. 5a, gorilla data indicate a significant correlation between the shoulder and elbow joints, underscoring their critical role in this action. By contrast, as illustrated in Fig. 5b, students’ imitations yield a shoulder–elbow correlation coefficient below 0.4, suggesting insufficient coordination in their performance. This discrepancy primarily reflects differences in the quality of imitation and does not undermine the inherent importance of the shoulder and elbow as key joints in chest-beating movements. Overall, the results from the correlation heatmaps indicate that joint movement in the gorilla chest-beating action is characterized by a clear pattern of high coordination in symmetric joints and relatively independent movement in asymmetric joints.

Based on these observations, we will employ a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the factors influencing the course score in animal exercise courses. Chest-beating emphasizes the coordination between symmetric and asymmetric joints in the upper body, while walking examines the synergy and stability of whole-body movement. This experimental design not only provides robust empirical evidence for biomechanical analysis but also offers valuable insights for educational practice.

To further investigate the biomechanical characteristics of these movements, we attempt to identify the core joints associated with chest-beating and walking by analyzing the contribution ratio of symmetric joint pairs to the overall correlation. For each joint \(i\), the absolute sum of its correlation coefficients with all other joints (excluding the diagonal elements) is computed as shown in Equation 3:

where:

-

\(\Sigma _i\) represents the total absolute sum of the correlation coefficients for joint \(i\);

-

\(C_{ik}\) denotes the correlation coefficient between joint \(i\) and joint \(k\).

For a symmetric joint pair \(i\) and \(j\), the contribution ratio is calculated as the proportion of their absolute correlation coefficient to the total correlation sum of joint \(i\), as shown in Equation 4:

where:

-

\(P_{i \leftrightarrow j}\) represents the contribution ratio of the symmetric joint pair \(i \leftrightarrow j\), reflecting its significance in the overall correlation of joint \(i\);

-

\(|C_{ij}|\) denotes the absolute correlation coefficient between the symmetric joint pair.

To better capture the joint dynamics of the imitated subject, we conducted a detailed correlation analysis of gorilla movements. In the chest-beating action, the contribution ratios of symmetric joint pairs are as follows: hip joints (38.4%), shoulder joints (36.5%), elbow joints (33.8%), knee joints (26.4%), and ankle joints (3.4%). Similarly, in the walking action, the contribution ratios are: hip joints (38.9%), knee joints (37.7%), shoulder joints (28.4%), elbow joints (12.9%), and ankle joints (12.1%).

Based on these rankings, the shoulder and elbow are identified as core joints for chest-beating, while the knee is dominant in walking, respectively. Notably, the hip joint remains a core joint in both movements, indicating its crucial role in gorilla locomotion and upper-body coordination. However, for instructional purposes, selecting joints that facilitate clearer demonstration is essential. Therefore, in the subsequent experiments, we will focus on the elbow and knee joints, as they provide a more intuitive reference for students to comprehend and replicate upper and lower limb movements effectively.

Analysis of influencing factors

In this study, we selected students of different genders and training statuses to investigate the impact of these factors on movement imitation performance. By comparing different groups, we aim to reveal the mechanisms through which these factors influence the imitation process.

Gorilla chest-beating

To better analyze the phases of the chest-beating motion, we segmented the motion data into two keyframes and conducted an in-depth analysis for each. Specifically, we analyzed the changes in elbow angles between the two frames, especially the differences in the left elbow angle (le\(\theta\)) and right elbow angle (re\(\theta\)).

We conducted multiple two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) on 54 experimental datasets to evaluate the effects of acting training status, gender, and their interaction on elbow joint angles during the two stages of the chest-beating action. These analyses were aimed at assessing the impact of acting training status, gender, and their interaction on the changes in elbow joint angles during the two stages of chest-beating. The two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) method provided key parameters, including degrees of freedom (df), mean square (MS), F-statistic (F), p-value (p), and effect size (ES).

Analysis of differences in right elbow angles between students and gorilla during chest-beating imitation

To explore the influence of gender and training status on the effectiveness of imitation, we utilized the Mann-Whitney U test to analyze the joint angle data during the chest-beating action. The analysis particularly focused on the variations in the re\(\theta\) between the gorilla and the students across the two stages of chest-beating. The parameters analyzed included the mean and standard deviation of the gorilla and human groups, the U-statistic, and the p-value.

In the subsequent analysis, we categorized the participants into four groups: Trained female subjects (TF), Untrained female subjects (UF), Trained male subjects (TM), and Untrained male subjects (UM).

As shown in Table 2, the average difference in the re\(\theta\) joint angle for the gorilla was 20.88 degrees, while the average difference for UF was 18.68 degrees. The Mann-Whitney U test results showed that the U statistic was 42 and the p-value was 1, indicating that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. This means that when UF imitated the chest-beating action, their re\(\theta\) joint angle was not significantly different from that of gorillas.

In the UM group, the average re\(\theta\) joint angle difference for gorillas was 20.88 degrees, while the average difference for UM was 17.13 degrees. The Mann-Whitney U test results showed a U statistic of 23 and the p-value was approximately 0.95, indicating that there was also no significant difference between the two groups. This means that UM also showed no significant difference in re\(\theta\) joint angle compared to the gorilla when performing the action.

In the TF group, the average difference in the gorilla’s re\(\theta\) joint angle was 20.88 degrees, while the average difference for TF was 46.65 degrees. The Mann-Whitney U test results for this group showed a U statistic of 24 and a p-value of 0.125. Although the p-value is close to 0.05, it does not reach the threshold for statistical significance. This suggests that TF exhibited some difference in their re\(\theta\) joint angle compared to the gorilla, but this difference was not statistically significant.

In the TM group, the average re\(\theta\) difference for the gorilla was 20.88 degrees, while the average difference for the TM group was 9.87 degrees. The Mann-Whitney U test results showed a U statistic of 49 and a p-value of approximately 0.53, indicating no significant difference between the two groups. Thus, the TM group did not show a significant difference in their re\(\theta\) joint angle compared to the gorilla when mimicking the chest-beating action.

Through the Mann-Whitney U test on the left elbow joint angle, we found that there were no statistically significant differences in the left elbow angle between different groups (UF, UM, TF, TM) and the gorilla during the chest-beating imitation. Specifically, the U statistic for the UF group was 46 with a p-value of 0.6260; for the UM group, the U statistic was 19 with a p-value of 0.5727; for the TF group, the U statistic was 14 with a p-value of 0.9307; and for the TM group, the U statistic was 48 with a p-value of 0.4941. All p-values were greater than 0.05, indicating no significant difference in the left elbow joint angle among these groups. This suggests that human participants showed a high similarity in their left elbow movement to that of the gorilla during the chest-beating action, validating the experiment’s reliability and supporting its methodological consistency across groups.

Two-way ANOVA for chest-beating: gender and training status

In the two-way ANOVA conducted on the re\(\theta\) angle, we examined the impact of training status and gender on the angle differences between Frame 1 and Frame 2 (Table 3). The analysis results showed that gender had a significant effect on the re\(\theta\) changes in angle \((F(1, 47) = 8.0186, p < 0.05, \eta ^2 = 0.0972)\). There was a significant difference in angle changes between males and females.

Although the main effect of training status on the re\(\theta\) angle changes was not significant \((F(1, 47) = 3.3303, p > 0.05, \eta ^2 = 0.0428)\), the interaction between training status and gender was significant \((F(1, 47) = 16.1312, p < 0.01, \eta ^2 = 0.1780)\). This suggests that the combination of gender and training status has a significant impact on the changes in re\(\theta\) angles, with trained males and females showing different re\(\theta\) angle changes when imitating the action.

Similarly, in the two-way ANOVA conducted on the le\(\theta\) angles (Table 4), the results showed that neither gender nor training status had a significant effect on the le\(\theta\) angles \((\text {Gender: } F(1, 47) = 2.7722, p> 0.05, \eta ^2 = 0.0518; \text {Training Status: } F(1, 47) = 0.6868, p > 0.05, \eta ^2 = 0.0134)\). Furthermore, the interaction between gender and training status also did not have a significant effect on the le\(\theta\) angles \((F(1, 47) = 0.2508, p > 0.05, \eta ^2 = 0.0049)\).

Overall, this indicates that gender, training status, and their interaction had no significant effect on changes in the le\(\theta\) angles, with subjects showing consistent performance regardless of these factors. In contrast, the right elbow re\(\theta\) angle exhibited significant changes based on gender and training status. This suggests that the right elbow contributes more critically to imitation performance, while the left elbow plays a comparatively minor role.

Gorilla walking

Analysis of differences in right elbow angles between students and gorilla in walking imitation

We also used the Mann-Whitney U test to analyze joint angle data in walking imitation. The parameters were consistent with those for the gorilla chest-beating action, with the core joints being the right knee (rk\(\theta\)) and left knee (lk\(\theta\)).

As shown in Table 5, the analysis of the right knee angle differences (rk\(\theta\)) compares the variations between different student groups and gorillas. For the UF group (untrained females), the mean right knee angle difference for gorillas was 35.96 degrees, while the UF group had a mean of 33.18 degrees. The U statistic was 52, and the p-value was 0.6640, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the UM group (untrained males), the mean right knee angle difference for gorillas was 35.96 degrees, while the UM group had a mean of 49.53 degrees. The U statistic was 52, and the p-value was 0.4320, also greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the TF group (trained females), the mean right knee angle difference for gorillas was 35.96 degrees, while the TF group had a mean of 18.07 degrees. The U statistic was 9, and the p-value was 0.0059, which is less than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the TM group (trained males), the mean right knee angle difference for gorillas was 35.96 degrees, while the TM group had a mean of 26.74 degrees. The U statistic was 29, and the p-value was 0.1490, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

In the analysis of left knee angle differences (lk\(\theta\)), for the UF group (untrained females), the mean left knee angle difference for gorillas was 32.48 degrees, while the UF group had a mean of 45.14 degrees. The U statistic was 80, and the p-value was 0.2094, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the UM group (untrained males), the mean left knee angle difference for gorillas was 32.48 degrees, while the UM group had a mean of 49.22 degrees. The U statistic was 62, and the p-value was 0.1003, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the TF group (trained females), the mean left knee angle difference for gorillas was 32.48 degrees, while the TF group had a mean of 24.46 degrees. The U statistic was 28, and the p-value was 0.3749, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups. For the TM group (trained males), the mean left knee angle difference for gorillas was 32.48 degrees, while the TM group had a mean of 31.18 degrees. The U statistic was 48, and the p-value was 0.9710, greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Overall, the results of the left knee angle difference analysis suggest that, regardless of training, the student groups’ left knee angle variations exhibit a high degree of similarity to the gorilla’s movement characteristics, especially in the trained groups (TF and TM), which displayed a closer resemblance to the gorilla, showing more accurate imitation. Although the untrained groups showed slightly higher left knee angle variations compared to the gorillas, these differences did not reach statistical significance, indicating a general similarity in the left knee movement during imitation. These results further support the comparability of data between gorillas and students, providing strong evidence for studying the patterns of human imitation of gorilla movements.

Two-way ANOVA for walking: gender and training status

As shown in Table 6, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the effects of training status and gender, as well as their interaction, on right knee angle variation. The results indicate that the factor of training status has a significant main effect on right knee angle differences (\(F = 8.878\), \(p = 0.0044\)). Furthermore, the effect size for training status is 0.8257, suggesting a strong influence of training status on right knee angle variation. This finding highlights the significant difference in right knee angle changes between individuals with and without training status, emphasizing the crucial role of training status in action imitation or motor training.

The main effect of gender was not significant (\(F = 0.6815\), \(p = 0.4129\)), with an effect size of 0.0634, indicating that gender has a weak influence on right knee angle differences and may not be a significant factor in this behavior. Similarly, the interaction between training status and gender did not reach statistical significance (\(F = 0.1922\), \(p = 0.6629\)), with an effect size of 0.0179, suggesting that the combined effect of training status and gender on right knee angle differences is negligible.

Table 7 presents the results of a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) examining the differences in left knee angle changes. The results show that the factor of training status has a significant main effect on left knee angle differences (\(F = 8.4437\), \(p = 0.0054\)). The effect size for training status is 0.6677, indicating a strong influence of training status on the left knee angle variation. This finding suggests that individuals with training status exhibit significantly better performance in left knee angle changes compared to those without training status, highlighting the critical role of training status in motor control and action imitation.

The main effect of gender was not significant (\(F = 3.0008\), \(p = 0.0892\)), with an effect size of 0.2373, indicating that gender has a weak influence on the left knee angle differences. The results suggest that gender plays a limited role in the variation of left knee angles and may not be a primary factor in explaining differences in this behavior. Furthermore, the interaction between training status and gender did not reach statistical significance (\(F = 0.2016\), \(p = 0.6553\)), with an effect size of 0.0159. This indicates that the effects of training status and gender on left knee angle differences are independent, with no significant synergistic interaction between the two factors.

Effects of gender and training status on imitation

This study investigates the effects of gender and training status on the imitation of gorilla chest-beating and walking movements. Overall, training status plays a significant role in imitation accuracy, particularly in the control of right elbow and knee angles, while the influence of gender appears more nuanced, exhibiting interaction effects in certain contexts.

In the chest-beating movement, variation in the right elbow angle is significantly influenced by the interaction between gender and training status. Trained female participants showed a difference approaching statistical significance in right elbow angle compared to gorillas, suggesting that training may enhance imitation precision. In contrast, variation in the left elbow angle was not significantly affected by either gender or training status, likely because the left elbow plays a less dominant role in the movement.

In the imitation of the walking movement, training status had a particularly strong effect on the right knee angle, with the trained female group demonstrating higher accuracy. The left knee angle exhibited smaller differences across gender and training status, indicating greater stability and reduced sensitivity to individual variation.

Overall, while gender may influence imitation accuracy in specific joints (such as the right elbow and right knee), the effect of training status on improving precision appears to be more substantial. This suggests that accumulated training experience is a more critical factor than gender in developing precise limb control during imitation. From a pedagogical perspective, improved joint-level accuracy contributes to enhanced performance skills. Therefore, in animal imitation courses, instructors may benefit from focusing feedback on core joints, thereby providing a more objective and targeted basis for student guidance.

These findings underscore the importance of training status in improving imitation accuracy, especially in the control of joint movement during expressive performance. However, given the relatively small sample size, particularly within subgroups such as trained females, the statistical power of subgroup analyses may be limited. Although the observed interaction effects between gender and training status provide valuable insights, they should be interpreted with caution. The use of joint angle normalization and a focus on core joints helped mitigate individual variability to some extent. Nonetheless, future studies with larger and more diverse participant groups will be necessary to validate and generalize these findings. This study serves as an initial attempt to validate the factors influencing imitation scoring and provides a preliminary foundation for related work. Future research will aim to expand the sample size and diversity, and incorporate additional potential variables to systematically investigate the multidimensional influences on imitation evaluation.

Broader applications

Although HPE-IBA was developed to score expressive imitation in acting training, the same joint-angle features and machine learning pipeline could be applied to a variety of other tasks. Recent work has shown that limb-joint trajectories can be used for person re-identification, such as identifying missing individuals or suspects based on gait 19. In sports, deep pose estimation has been harnessed to build “AI coaches” that provide personalized technique feedback in real time 29. In ecology and ethology, pose-based machine learning methods are now used to classify animal behaviors from video 30. These examples highlight the versatility of our structural pose representations and suggest a broad range of future extensions for HPE-IBA.

Conclusion

This study delves into the evaluation methods in acting education and conducts a quantitative analysis of imitative behavior in animal exercise courses, revealing the impact of different training statuses and gender factors on imitative performance. We propose HPE-IBA, a MediaPipe-based quantitative analysis framework, to assess students’ performance in imitation exercises, with a particular focus on mimicking gorilla chest-beating and walking. This framework provides scientific support for objective evaluation and offers technical assistance for optimizing acting instruction. Furthermore, it holds the potential for flexible application to other motion scenarios.

Through correlation analysis of joint angle variations during the imitation of gorilla chest-beating and walking, we verified the weak correlation between joint angle changes in gorillas and students. Based on the high coordination observed in gorilla movements, the core joints for different actions were identified. This finding lays a theoretical foundation for future analyses of imitative behavior, suggesting that teachers should focus on guiding core joints, rather than relying on subjective observations. Additionally, this discovery provides reliable support for joint data analysis, helping to mitigate the complexity of models when analyzing multiple joints simultaneously. In analyzing the imitative actions of students with different genders and training statuses (trained vs. untrained), we reveal the interaction effects of gender and training status on imitative behavior through two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Specifically, training status significantly influenced the joint angles of the elbow and knee, while gender differences manifested in the coordination of certain joints. These results provide important insights for personalized teaching strategies in acting education, particularly when addressing students’ gender and training backgrounds.

Overall, this study emphasizes the value of quantitative analysis in imitative behavior for acting education. By focusing on joint angle changes and coordination, teachers can provide more precise feedback to help students correct deviations in their movements. Especially for students of different genders and training backgrounds, teachers can offer tailored suggestions based on the characteristics of joint movements, thereby enhancing the fairness and effectiveness of teaching. This study not only provides a scientific assessment method for acting education but also paves the way for future advancements in teaching research and technological applications.

The current study primarily focuses on two complex imitative actions, gorilla chest-beating and walking, which represent only a subset of imitative behaviors and thus have some limitations. Additionally, since MediaPipe is trained on human data and not explicitly validated on non-human primates, the extracted keypoints from gorilla videos should be interpreted with caution. To improve robustness in cross-species contexts, subsequent work may explore domain adaptation or the development of custom pose models. We also plan to expand the scope of analysis to include a wider variety of animal behaviors, providing a broader perspective for the application of this framework across different motion scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to generate the results presented in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adrian, B. Actor Training the Laban Way: An Integrated Approach to Voice, Speech, and Movement (Simon and Schuster, 2024).

Kissel, H. Stella Adler: The Art of Acting (Hal Leonard Corporation, 2000).

Huikai, L., Yuanhui, Y. & Yongsheng, C. Literature review on drama education research in China. New Generation: Theoretical Edition 231–232 (2020).

Zheng, C. et al. Deep learning-based human pose estimation: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 56(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3603618 (2023).

Shah, S. M. S., Malik, T. A., Khatoon, R., Hassan, S. S. & Shah, F. A. Human behavior classification using geometrical features of skeleton and support vector machines. Comput. Mater. Continua 61, 535–553. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2019.07948 (2019).

Arif, A. et al. Human pose estimation and object interaction for sports behaviour. Comput. Mater. Continua 72, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.023553 (2022).

Chauhan, R., Dhyani, I. & Vaidya, H. A review on human pose estimation using mediapipe. In 2023 3rd International Conference on Innovative Sustainable Computational Technologies (CISCT), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISCT57197.2023.10351240 (2023).

Kim, J.-W., Choi, J.-Y., Ha, E.-J. & Choi, J.-H. Human pose estimation using mediapipe pose and optimization method based on a humanoid model. Appl. Sci. 13(4), 2700. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042700 (2023).

Chen, L., Liu, T., Gong, Z. & Wang, D. Movement function assessment based on human pose estimation from multi-view. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 48, 321–339. https://doi.org/10.32604/csse.2023.037865 (2024).

Sawyer, S. F. Analysis of variance: the fundamental concepts. J. Manual Manip. Ther. 17, 27E-38E (2009).

Chen, Y., Li, L. & Li, X. Correlation analysis of structural characteristics of table tennis players’ hitting movements and hitting effects based on data analysis. Entertain. Comput. 48, 100610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2023.100610 (2024).

Senthilnathan, S. Usefulness of correlation analysis. Available at SSRN 3416918 (2019).

Fagerberg, P., Ståhl, A. & Höök, K. Designing gestures for affective input: An analysis of shape, effort and valence. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, 57–65 (ACM, 2003).

Demšar, U. et al. Establishing the integrated science of movement: bringing together concepts and methods from animal and human movement analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 35, 1273–1308 (2021).

Lan, Z. & Xu, M. Correlation analysis of driver fatigue state and dangerous driving behavior. In Proceedings of China SAE Congress 2022: Selected Papers (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2023).

Mitrović, K. & Milošević, D. Pose estimation and joint angle detection using mediapipe machine learning solution. In Serbian International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence 109–120 (Springer, 2022).

Kim, B. H. et al. Measurement of ankle joint movements using imus during running. Sensors 21, 4240. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21124240 (2021).

Wu, B., Zhu, Y., Nishimura, S. & Jin, Q. Analyzing the effects of driving experience on prebraking behaviors based on data collected by motion capture devices. IEEE Access 8, 197337–197351. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3034594 (2020).

Topham, L. K., Khan, W., Al-Jumeily, D. & Hussain, A. Human body pose estimation for gait identification: A comprehensive survey of datasets and models. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–42 (2022).

Stanislavski, C. An Actor Prepares (Routledge, 1989).

Adler, S. The Technique of Acting (Bantam, 1990).

González-Badillo, J. J., Sánchez-Medina, L., Ribas-Serna, J. & Rodríguez-Rosell, D. Toward a new paradigm in resistance training by means of velocity monitoring: a critical and challenging narrative. Sports Med.-Open 8, 118 (2022).

Shuhei, F. Animal exercise: Its content and practice. Research in Arts, Nihon University College of Art, 59–70 (2000).

Chunyan, B. & Yue, L. Survey on video-based human action recognition based on deep learning. J. Graph. Stud. 44, 625–639 (2023).

Nan, Z. & Jianshe, Z. Construction of a multimodal emotion semantic database for learning behavior in language intelligence scenarios. Language and Applied Linguistics, 121–131 (2023).

Gogtay, N. J. & Thatte, U. M. Principles of correlation analysis. J. Assoc. Phys. India 65, 78–81 (2017).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge, 2013).

Mukaka, M. M. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 24, 69–71 (2012).

Wang, J., Qiu, K., Peng, H., Fu, J. & Zhu, J. Ai coach: Deep human pose estimation and analysis for personalized athletic training assistance. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM ’19 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2019).

Kleanthous, N. et al. A survey of machine learning approaches in animal behaviour. Neurocomputing 491, 442–463 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all study participants for their invaluable cooperation. Each participant signed written informed consent forms, consenting to the publication of anonymized images in this online open-access article and understanding their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. We also appreciate their adherence to the health and safety measures implemented throughout the data collection period. No real names or other identifiable information appear in this manuscript. We also wish to express our sincere gratitude to Bo Wu for his guidance, support, and valuable feedback throughout this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and C.Z. contributed equally to this work. Y.Q. conceived the study and designed the experiments. C.Z. designed the methodology, performed data preprocessing, and conducted the statistical analysis. S.X. collected data and assisted with visualization. B.W. supervised the project, provided funding support, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, Y., Zhang, C., Xiong, S. et al. A framework of imitative behavior analysis for animal exercise courses via human pose estimation. Sci Rep 15, 40182 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23829-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23829-8