Abstract

Energy Management of PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities integrates RES, such as PV panels, WT, battery ESS, and the grid to optimize energy utilization, enhance sustainability, and reduce reliance on conventional energy sources. At the same time, the system has to address problems in balancing costs and efficiency, because the rise in RE like PV and wind, and the need for ESS and grid integration, can make it harder to match supply and demand. To address these issues, this paper proposes a hybrid strategy for EM in PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities. The hybrid method integrates the POA and GENN. The main aim is to reduce operational costs and improve the energy efficiency of the PV-powered lighting system. POA is utilized to optimize energy allocation among RES, the grid, and energy storage, enhancing resource utilization and maintaining supply-demand balance. While GENN is utilized to predict energy generation and consumption patterns, it enhances the accuracy of forecasting for improved system performance. By then, the proposed method is implemented on the MATLAB platform and evaluated with various existing approaches. The POA-GENN approach achieves an operational cost of 365.24 €ct and an efficiency of 99.2%, demonstrating its effectiveness in optimizing the EM of PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The EM strategy for PV-powered lighting in smart cities uses RES such as PV panels and WT to help cut back on energy from conventional sources1. The system relies on ESS, for instance, battery ESS, that stores any surplus energy made during the day to use when there is less renewable energy2. EM technology makes sure resources are shared properly among PV, wind, storage, and the grid, achieving constant and reliable electricity for public lighting3. The lighting system changes with demand and supply of energy, so the lights keep working as expected even when solar or wind power changes4. Smart control systems are employed to manage energy distribution efficiently across different urban zones, from dense city centers to suburban areas, ensuring that lighting needs are met while avoiding overconsumption5. Grid interaction is facilitated to provide backup power and balance supply-demand fluctuations when renewable energy generation is insufficient6. The approach contributes to improving energy efficiency and promoting sustainability in urban infrastructure7. Scalability means the system can be put into use in different city settings to supply energy and meet various infrastructure requirements8. Integrating RES, including PV and WT, supports a future free of energy dependence and relies less on non-RES9. Lastly, the system helps urban infrastructure become more environmentally friendly by replacing traditional energy sources with clean alternatives, which helps make cities more environmentally friendly10.

Challenges

PV-powered lighting systems bring many benefits, but handling their costs and efficiency is still quite challenging. One problem is that solar irradiance changes often, causing energy to be produced unevenly and making it difficult for systems to estimate their available energy, reducing their efficiency. To compensate, oversized PV arrays or additional storage capacity are often deployed, increasing capital and maintenance costs. Moreover, the integration of ESS, while essential for reliability, introduces cost burdens associated with battery degradation, replacement cycles, and system upkeep. Energy losses due to inefficient power conversion, poor load forecasting, and suboptimal energy dispatch further diminish overall system performance. Managing city lighting systems in a range of urban areas with different kinds of lighting and conditions requires smart, adjusting control systems, adding to the overall system expenses. With these obstacles present, it is still difficult to have effective, efficient, and affordable EM in urban lighting powered by PV systems. Table 1. Shows Challenges in Existing Models.

Literature survey

Several research studies have focused on PV EM in smart systems with different techniques. A review of some of these works is provided below.

The research in11 have presented two effective methods for optimizing the training of a FFNN for sensor-less control of PV converters in DC nanogrids: EMA and SCSO. The network parameters were adjusted using these algorithms to precisely estimate PV output current based on inputs like voltage, temperature, and solar irradiation. This approach helps to make the system more stable since the current, failing sensors are replaced with a predictive model. The technique improved the way PV-powered nanogrid systems work and effectively managed nonlinear regression estimation. The research in12 have introduced the PSO-RNN to optimize energy dispatch in smart island systems. Using the improved PSO algorithm, this technique ensures system balance and lowers operating costs by figuring out the best way to distribute energy among energy storage, renewable sources, and interruptible loads. EM choices in grid-connected operations were made more accurately and efficiently when the RNN was used to forecast renewable energy outputs like PV and wind.

The research in13 have developed the CCG, which was a DL-based method for predicting indoor temperatures. CCG effectively controls power consumption for all household appliances, including ESS charging and discharging, by coordinating device-specific limitations. The DNN predicts the temperature inside, which was a crucial component that affects how well air conditioners perform. This combination strategy maintains user comfort through intelligent, flexible appliance scheduling while increasing energy efficiency and lowering home energy costs.

The study in14 have presented the ANN to maximize solar-powered display refrigerator performance. This method uses an ANN in conjunction with a variable speed drive to control the compressor’s working frequency in response to environmental factors and cooling requirements. Implementing ANN-enabled adaptive control leads to a higher coefficient of performance, reduces the amount of electricity used, and boosts energy efficiency. The method aims to keep the system running at peak performance by meeting thermal needs, solar energy power, and sustainability.

The research in15 have introduced the BSFAO approach for partial shade MPPT in PV systems. The problem of tracking multiple MPPs brought on by uneven solar irradiation was addressed by this hybrid approach. Using BSFAO, MPPT can be increased for indoor energy harvesting in smart homes by rapidly finding the global peak power point, which improves energy efficiency and allows fast tracking under a variety of changing weather conditions.

The research in16 have developed an ABC algorithm to optimize the LCC evaluation of PV systems for a variety of load and climate scenarios in a few Indian smart cities. The algorithm aimed to recommend the best PV system setup considering price, energy output, upkeep expenses, and potential carbon credit advantages. This optimized technique allows more precise long-term cost checking and helps ensure sustainable city energy infrastructure.

The study in17 have presented an improved LSTM-based optimal home micro-grid EM technique to effectively control energy production, storage, and consumption in homes using PV and battery ESS. The method provided an accurate prediction of PV-generated energy using a better LSTM that can adapt to changes in energy flows. This strategy reduces dependency on traditional energy sources while increasing energy efficiency, facilitating cost-effective decision-making, and advancing the integration of renewable energy into residential micro-grids by effectively adapting to fluctuating energy demands and solar intermittency.

A day-ahead smart electricity market for a decarbonized microgrid structure with a demand response program was proposed in18. The approach reduced carbon emissions and operating costs. The IEEE 33-bus system served as a demonstrative instance to validate the implementation of the smart power market model in a substantial real-world system. The model employed the AVOA to optimize operational costs based on generation capacity, energy prices, and current load demand. The findings indicated that energy expenditures and PAR were diminished, along with carbon emissions, while the DI remained at a minimal level.

An efficient energy management strategy for the optimal control of the MG utilizing advanced MILP was developed in19. Additionally, a DSM mechanism utilizing MILP was proposed for an internet of things-enabled grid. The MG was modelled in MATLAB, employing a dual-level communication framework to connect to the server in the cloud. Global and local communication was enabled by MQTT and TCP/IP protocols, appropriately. Finally, the simulation model incorporated distributed generators, like PV and wind turbines, together with a hybrid microgrid, suited to many scenarios, including residential structures and small commercial buildings.

A hybrid approach for optimal management of energy in a grid-connected hybrid power station that incorporates a battery was developed in20. The hybrid approach integrated the SAO technique with the MDDNN. The SAO-MDDNN method was employed to enhance the battery’s longevity. The battery ESS has been optimized for efficiency through the SAO method. The MDDNN was employed to forecast power consumption. The SAO-MDDNN technique exhibited considerable potential for enhancing the management of energy in hybrid RES, providing increased environmental advantages, cost savings, and efficiency.

A hybrid approach for a PV-powered grid system with a PI controller was designed in21 to enhance power quality. The hybrid strategy involved the simultaneous execution of the CMBO and the PCSANN. The CMBO technique was employed to minimize the total harmonic distortion of the system, while the PCSANN method was utilized to predict the optimal solution for the overall system. The CMBO-PCSANN logic controller calibrated the proportional–integral controller to regulate the voltage and current of the grid-fed inverter. This enhanced overall power quality of the system and facilitated a rapid response to diverse disturbances in load and inputs. The CMBO-PCSANN model reduced the total harmonic distortion of the system.

A hybrid methodology for the management of energy across several MGs incorporating electric vehicle charging was proposed in22. The hybrid technique entailed the concurrent application of GJO and PCGAN. The GJO technique was to optimize the energy management of many MGs with electric vehicle charging. The electric vehicle’s discharging and charging schedules were optimized with the GJO methodology. The PCGAN methodology was employed to predict the optimal EV control system. The model effectively handled the energy of many microgrids with electric vehicle charging, while reducing carbon emissions, operational costs, and transmission losses.

The operational optimization of IEDSs was carried out by employing a hybrid method for the unbalanced operation of the power distribution system to achieve optimal energy flow23. The hybrid methodology integrated the LSO with vCANNs. LSO was employed to enhance the load flow of the imbalanced radial distribution electrical network. vCANN was utilized to forecast the energy distribution of natural gas and thermal networks. The model optimized the total operational cost in the most economical manner to distribute energy throughout the integrated model while satisfying demand and network restrictions.

A hybrid RES comprising PV, WT, and fuel cell components was developed in24 for both grid-connected and stand-alone configurations, emphasizing capacity and cost credits to assess dependability and cost effectiveness. The systems were designed to reduce costs while enhancing dependability, demonstrating that the grid-connected system attains a 13.1% decrease in overall cost, amounting to 73.016 million dollars, compared to the stand-alone system at 84.025 million dollars, with comparable reliability rates of 97.58% versus 97.22%. Furthermore, the grid-connected system demonstrated enhanced energy use, decreasingwaste energy by 34.2%. The independent system attained capacity credit of 1.08 MW compared to 1.01 MW, owing to its complete dependence on renewable energy sources.

A cost-effective scaling methodology for battery ESS in grid-connected microgrids utilizing the ARO technique was proposed in25. The model integrated economic and technical factors, encompassing depth-of-discharge restrictions, initial battery SOC, and several wind turbine models. The result analysis validated the resilience of the methodology against variations in wind turbine and PV power, battery efficiency, and load demand. The findings demonstrated the efficacy and computational efficiency of ARO for practical and adaptable management of microgrid energy.

The literature comparison of different optimization techniques for PV EM in smart systems is illustrated in Table 2.

Research gap and motivation

Despite the significant advancements in energy system optimization techniques, several research gaps persist, particularly in balancing operational cost reduction with enhanced system efficiency in diverse and dynamic environments. Existing approaches such as EMA, SCSO, PSO-RNN, and DL-based strategies have demonstrated effectiveness in specific applications like sensor-less control, indoor temperature prediction, and partial shading conditions. However, many of these techniques are limited by context-specific applicability, insufficient coordination of multiple energy sources, and a lack of comprehensive frameworks that simultaneously address prediction accuracy, adaptive control, and economic performance. Moreover, current methods often overlook integrated strategies that optimize both technical performance and financial sustainability. The motivation for this research is driven by the need to develop a flexible and robust optimization approach that not only improves EM and system responsiveness but also supports operational cost reduction and increased efficiency, enabling smarter, more sustainable energy infrastructures in evolving smart city environments. Electrical networks must systematically implement, regulate, and enhance renewable energy sources to ensure stability on the grid and power supply security. AI and other intelligent methodologies are powerful tools capable of reducing costs, improving system efficiency, addressing the complexities of the global energy transition, and accelerating the decarbonization process. They are mostly utilized for energy demand control, optimization of grid operations, and prediction of renewable energy supply and consumption26.

Several existing software-based approaches to energy management for renewable systems manifest some key limitations: (i) accuracy of prediction is fairly limited as the conventional machine-learning approach or single neural network often fails to take into account the nonlinear variation of solar irradiance, wind speed, and load patterns; (ii) low optimization performance: standard meta-heuristics like PSO or GA may often lead to a local optimum with suboptimal scheduling decisions; (iii) lack of adaptability, since most frameworks tackle forecasting and optimization as independent separate components instead of complementary and iterative ones; and (iv) computational limitations: several tools do not deliver trustworthy results for a large-scale smart city scenario. The proposed framework, which integrates GENN-based forecasting with POA-based optimization, deals with these solutions by offering higher-accuracy demand and generation prediction, a robust global search ability for energy allocation optimization, an iterative scheme for forecasting and optimization interaction, and computationally efficient performance for real-time smart city applications.

Contribution

The main contribution of this manuscript is summarized as follows:

-

The proposed POA-GENN technique presents a hybrid strategy for EM in PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities, addressing challenges related to minimizing operational costs and maximizing energy efficiency.

-

POA is utilized to optimize energy allocation among PV, wind, ESS, and the grid, ensuring balanced supply-demand management and efficient resource utilization.

-

GENN is employed to predict energy generation and consumption patterns, enabling accurate forecasting and better decision-making for energy distribution.

-

This proposed method is applied in MATLAB and is compared to PSO-RNN, ANN, BSFAO, LSTM, and CCG-DNN to prove its effectiveness.

-

The POA-GENN method shows that it can significantly lower costs and achieve greater energy savings than other techniques.

Research novelty & objectives

The novelty of this research lies in the integration of POA with GENN towards renewable-integrated smart city energy management. While forecast-optimization integrations were already done, these approaches suffer from (i) the tendency of an optimizer towards premature convergence and (ii) the inability of a predictor to capture multi-source correlations. On the contrary, the unique combination of scent-diffusion and adaptive trail-following movement in POA provides a better compromise between global exploration and local exploitation, whereas GENN utilizes both graph structure and ensemble diversity to lessen forecasting variance and fortify itself against intermittency. Together, POA and GENN utilize forecast-informed optimization in which accurate renewable/load forecast directs adaptive scheduling decisions to minimize cost and stabilize the system. This study is the first attempt to deploy POA for energy scheduling and to integrate it with GENN for renewable forecasting, hence making the proposed POA-GENN a novel hybrid formulation in contrast with existing optimization-forecasting models.

The primary objectives of this research are defined as follows:

-

To develop an accurate forecasting framework by employing a GENN to predict renewable energy generation and load demand, thereby reducing uncertainty in decision-making.

-

To design an efficient optimization strategy using the POA to allocate resources (PV, wind, ESS, and grid) under operational and system constraints.

-

To integrate forecasting and optimization iteratively, such that forecasting results dynamically guide optimization, and optimization outcomes refine forecasting model requirements, achieving continuous improvement in system performance.

-

To minimize operational cost and enhance energy efficiency of PV-powered smart city lighting systems while ensuring supply–demand balance and maintaining system stability.

-

To compare the model against existing approaches to validate the effectiveness of the proposed POA-GENN model in terms of cost, reliability, and efficiency.

The paper’s remaining section is arranged as follows: The configuration of the EM system with RES for PV-powered lighting in smart cities is explained in Part 2. The POA-GENN approach for minimizing the operational cost of the MG system is described in Part 3. The results and discussion are presented in Part 4. In such a manner, the manuscript is concluded in Part 5.

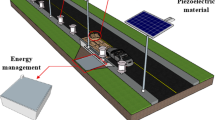

Configuration of EM system with RES for PV-powered lighting in smart cities

Figure 1 illustrates the configuration of an EM system with integrated RES for PV-powered lighting in smart cities. The system utilizes PV panels and WT as primary RES to generate electricity, reducing reliance on conventional grid power. The generated power is monitored and distributed through a smart meter that communicates bi-directionally with an EM controller. This controller intelligently allocates power across various loads, including residential appliances and public lighting systems. A key feature is the inclusion of an ESS, which stores excess energy during periods of high-RES generation and supplies power when renewable availability is low, thereby enhancing system reliability. The lighting system, represented as a dedicated load, receives power through DC lines, ensuring efficiency and stability in urban lighting. Communication flows facilitate dynamic control and optimization based on energy availability, demand, and cost. Grid integration ensures power backup during low RES output, maintaining uninterrupted lighting. The EM system adapts to varying energy scenarios, ensuring efficient utilization of available resources. By combining smart control, renewable integration, and storage, the configuration supports a sustainable, energy-efficient lighting infrastructure tailored for modern smart cities.

Modeling of energy storage system

A battery ESS is a crucial component of the MG system under discussion; it can stabilize the variation of RES production, efficiently decouple generation and consumption across time, and resolve the intractable conflict between energy supply and demand27. Equation (1) is used to establish a mathematical operating model for battery ESS.

Here, \(\:{Z}_{t}^{ESS,u},{Z}_{t}^{ESS,v}\) are the battery \(\:ESS\) input and output power, respectively, and \(\:{Z}_{t}^{ESS}\) denotes the battery \(\:ESS\) functioning at time step \(\:t\). The status at the prior time step \(\:t-1\) is connected to the battery \(\:ESS\) current capacity at time slot \(\:t\) is shown by Eq. (2).

Where \(\:\xi\:\) is the \(\:ESS\) loss factor, \(\:{\omega\:}_{c}\) and \(\:{\omega\:}_{d}\) is its charging and discharging efficiency, and \(\:{R}_{t}^{ES}\) is the \(\:ESS\) capacity at time slot \(\:t\). The \(\:ESS\) remaining capacity and charging/discharging power are constrained at time slot \(\:t\) by:

Where, \(\:{Z}_{max}^{ESS}\) is the maximum charging/discharging power that can be used in a specific period of time \(\:\varDelta\:t\), \(\:{R}_{min}^{ES}\) and \(\:{R}_{max}^{ES}\) are the \(\:ESS\) lowest and highest remaining capacity limitations, respectively.

Battery degradation considerations

As well as SOC and power constraints, cycling behavior largely dictates the practical life span of the ESS because frequent deep discharges and rapid charge–discharge transitions accelerate the degradation of the battery and reduce its usable capacity, leading to increased replacement costs. To consider this factor, therefore, a degradation cost term is incorporated into the objective of the optimization:

where \(\:{c}_{cycle}\) is the cost per equivalent full cycle (€), \(\:{Q}_{throughput}\) is the charge throughput accumulated (Ah), and \(\:{Q}_{rated}\) is the nominal capacity (Ah). This proxy tracks the wear that is due to cycling within the simulation horizon. By minimizing operational cost and degradation cost, POA-GENN causes the ESS to operate within recommended SOC limits, bypass unnecessary deep cycles, and eventually enjoy longer life.

Modeling of photovoltaic

The output power of solar PV is dependent on both ambient temperature and irradiance. Using the beta PDF as in Eq. (6), these unknown parameters are modeled28.

Where solar irradiance is shown by \(\:m\). The beta PDF parametric values \(\:\gamma\:\) and \(\:\omega\:\) are calculated from the mean irradiance value in Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively.

Where, \(\:{\sigma\:}^{2}\) stands for standard deviation and \(\:\beta\:\) for the irradiance mean value. The beta PDF Eq. (9) is used to calculate the solar power.

Solar PV power output is displayed in Eq. (9).

In this work, the PDF is used to describe the normalized solar irradiance. The Beta distribution is very appropriate for irradiance values because (i) its support is bounded and ranges from 0 to 1, which perfectly fits normalized values of solar radiation; (ii) it is a very flexible distribution allowing a number of shapes (symmetric, skewed, unimodal, or bimodal), and therefore it can portray different sky conditions, from clear to cloudy, depending on and ; and (iii) it has been consistently applied in previous works on solar irradiance and PV performance modeling. Some alternative distributions, such as Gaussian or Weibull, could, however, be considered lesser choices because the former extends into negative values, whereas the latter is unbounded; both cases are unphysical regarding the range of irradiance data. Therefore, the Beta-PDF remains an appropriate mathematically consistent choice for PV-irradiance modeling, as considered in this work.

Modeling of wind turbine

The kinetic energy of the wind is transformed into mechanical energy by the WT29. The turbine rotor blades’ aerodynamic power \(\:{P}_{a}\) can be stated as follows.

Where, \(\:{P}_{v}\) is the kinetic power of the wind; the energy coefficients or \(\:{E}_{c}\) are determined by the turbine tip speed ratio \(\:\left(\sigma\:\right)\) and the blade pitch angle \(\:\left(\gamma\:\right)\). \(\:{D}_{t}\), \(\:\rho\:\) and \(\:{v}_{t}\) stand for the WT’s blade area, air density, and wind speed, respectively. The turbine tip speed ratio can be expressed as follows:

The following equation provides the aerodynamic torque \(\:{T}_{a}\).

Typically, the wind resources in an urban environment are considered less favorable when compared to open rural settings due to turbulence, wake interaction, and relatively low average wind speeds; however, there has been a recent surge in interest with respect to deploying small-scale and building-integrated wind turbines for the purpose of distributed energy generation in smart cities. These small-scale wind and solar power systems have been proven to provide complementary hybrid RES systems with wind energy during periods of minimum solar activity (e.g., evening, or cloudy days), thus improving the overall hybrid system’s reliability. Hybridization with PV and ESS further solves problems posed by standalone urban wind in rectifying large fluctuations and providing increased energy availability. The POA-GENN framework explicitly takes wind variability into account across the forecasting-optimization loop, providing adaptive scheduling even under very harsh conditions of urban wind. This justifies the usefulness of the model in city-scale applications wherein diversified renewable integration is of essence.

Modeling of AC grid

The grid is regarded as a low-voltage, three-phase network with a conventional network link. Here \(\:{I}^{{\prime\:}}\) means the inverter current, \(\:{I}_{X},{I}_{Y},{I}_{Z}\) is the three-phase current, \(\:{w}_{XZ}\) and \(\:{w}_{YZ}\) denotes the public grid voltages between phases, \(\:X,Y,Z,\) respectively30.

Equations (14–16) express the grid modeling Eq.

Where, \(\:{g}_{X}\) and \(\:{g}_{Y}\) is the inverter control variable, \(\:{h}_{X},{h}_{Y},{h}_{Z}\) denotes the sample voltages of the three phases, and \(\:{w}_{XZ}^{{\prime\:}},{w}_{YZ}^{{\prime\:}}\) represents the output inverter voltages between phases \(\:X\) and \(\:Z\), \(\:Y\) and \(\:Z,\) respectively.

Proposed POA-GENN approach to minimize the operational cost of the EM system

The proposed POA-GENN approach aims to minimize the operational cost of the EM system by optimizing energy allocation between RES, the grid, and ESS using the POA. Meanwhile, the GENN improves the accuracy of energy generation and consumption forecasting, enabling more efficient management of resources and ensuring a balance between supply and demand, ultimately reducing costs, and enhancing system performance. Figure 2 depicts the problem–solution flowchart of the proposed research. The flowchart shows the input resources (PV, WT, ESS, grid), the problem formulation (forecast demand/supply, cost minimization), the GENN-based forecasting stage, the POA-based optimization stage, and the outcome: an optimized energy management strategy for PV-powered lighting systems in smart cities.

The integration of GENN and POA is performed in a sequential-iterative manner. GENN generates PV generation and wind generation and load demand for the next time step, based on present system conditions, at every time-interaction interval. These forecast values are fed as inputs to the POA, which determines the schedule for dispatching energy from PV, WT, ESS, and grid to minimize operating costs subject to technical constraints. After realizing the optimized schedule for that time interval, the system states are updated and GENN generates a fresh load forecast for the subsequent time interval. This brings about an iterative forecast → optimize → update cycle, whereby GENN works to reduce input uncertainty, and POA schedules resources in response. Such an integration keeps the architecture robust with respect to dynamically emerging changes in the environment and circumvents the disintegration prevalent in conventional forecasting–optimization approaches.

Perfumer optimization algorithm

POA is a nature-based metaheuristic that imitates the behavior of scent diffusion and trail-following exhibited in the perfumery dynamics. It works because artificial agents, such as perfume molecules, search through a solution space using sensing and detecting scent gradients, aiming to attain a balance between exploration and exploitation. This algorithm is particularly suitable for solving complex, multi-objective optimization problems due to its adaptive searching ability and resistance to premature convergence. Its lightweight structure and flexibility make it well-suited for optimizing EM in smart city infrastructure, such as lighting systems, by efficiently allocating resources and improving energy efficiency while minimizing costs and environmental impact31. POA is utilized to optimize energy allocation among RES, the grid, and energy storage, enhancing resource utilization andmaintaining supply-demand balance.

The POA is a population-based metaheuristic lying behind nature, where a molecule of perfume diffuses into the atmosphere while an agent trails the path of increasing scent intensity. A unique aspect of POA is that it strikes a balance between exploration (scent diffuses all over the search space) and exploitation (trail-following of promising solutions adaptively).

Initialization: The search space is D-dimensional with lower and upper bounds of \(\:{L}_{d}\) and \(\:{U}_{d}\) respectively. A solution population of size N is initialized as follows:

Evaluation of fitness: The fitness of each solution is determined by means of the objective function \(\:f\left({X}_{i}\right)\). The best solution of iteration \(\:t\) is marked by \(\:{X}_{best}^{t}\).

Scent diffusion (exploration): In order to probe new regions, each agent diffuses its own scent in the search space. The update rule is defined as follows:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) is a diffusion coefficient that decreases linearly with iterations to make the solution path gradually less random.

Trail-following (exploitation): Agents follow stronger scent trails (best-performing solutions) at varying probability.

where \(\:\beta\:\) is a following coefficient that grows with iteration count to instill stronger exploitation near convergence.

Adaptive balance of exploration and exploitation: At each step, the agents’ update will be chosen as follows:

where \(\:{p}_{explore}\) dynamically decreases from 0.8 to 0.2 as iterations progress, allowing a smooth transition from global exploration to local exploitation.

Termination Criterion: This process is repeated until the maximum number of iterations \(\:{T}_{max}\) is reached or convergence is detected.

Step 1: Initialization

Set up the input parameters such as battery SOC, solar irradiance, and grid power.

Step 2: Random generation

After initialization, random vectors are generated to produce diverse energy distribution scenarios among PV, WT, the grid, and ESS.

Where \(\:n\) denotes the number of energy allocation parameters and \(\:M\) represents the population size reflecting multiple energy sharing strategies.

Step 3: Fitness function

The objective is to minimize the operational cost of the energy system while ensuring supply-demand equilibrium.

Here, \(\:Z\left(t\right)\) indicates the system’s operational cost from using different energy sources and storage operations.

Step 4: Exploration phase

This phase represents a broad design search, where energy allocation configurations undergo substantial variations. Similar to experimenting with diverse combinations in perfumery, the POA generates diverse candidate strategies for distributing energy among PV, WT, grid, and ESS.

The best and worst energy allocation strategies in the population are used to establish reference solutions for each candidate. The reference energy allocation is established by Eq. (23):

Assuming that \(\:re{f}_{u}\) is the reference allocation for the \(\:{u}^{th}\) candidate, \(\:{Y}_{B}\) and \(\:{Y}_{W}\) are the best- and worst-performing allocation configurations in the current population, respectively, \(\:r\) is a random number inside [0,−1] and \(\:I\) is a random number chosen from the set {1,2}.

The newly derived energy allocation strategy is evaluated and updated if it improves the objective function, as expressed in Eq. (24):

The updated fitness value for this new allocation is represented by:

Here, \(\:{E}_{u}^{S1}\) is the updated operational cost value.

Step 5: Exploitation phase

This stage performs local tuning around the most promising energy allocation designs. Here, small but strategic changes are made to optimize energy sharing effectiveness without significantly altering distribution properties. The updated energy allocation is expressed as Eq. (26).

Here, \(\:{Y}_{u}^{S2}\) is the refined energy allocation strategy, \(\:{E}_{u}^{S2}\) is the new fitness score assessing how well the allocation balances energy supply and demand, \(\:r\) is a random value between 0 and 1, and \(\:t\)is the iteration timer.

Step 6: Termination

Once the termination condition is satisfied, the algorithm finalizes the most effective energy allocation strategy that coordinates energy flow between various RES, the grid, and ESS. This ensures optimal utilization of available resources while maintaining the balance between supply and demand. If the termination condition is not met, the process continues iterating, refining allocation strategies to achieve an optimal solution. The pseudocode of the POA is presented in the following.

Graph ensemble neural network

GENN is an advanced deep learning framework that integrates multiple graph-based neural models to enhance predictive efficiency and system adaptability32. GENN uses ensemble learning to unite multiple Graph Neural Network (GNN) structures, which enable it to detect advanced patterns and relationships in structured data. This approach addresses the limitations of individual models by aggregating diverse feature representations, ensuring higher accuracy and improved decision-making. Additionally, GENN adapts to evolving conditions by dynamically adjusting its learning process based on variations in graph structures. GENN is utilized to predict energy generation and consumption patterns, enhancing the accuracy of forecasting for improved system performance. GENN performs forecasting of renewable generation (i.e., PV and wind) and load demand, which then act as inputs into the POA-based optimization stage.

Graph construction:

-

Nodes: Each distributed energy resource (DER) is represented as one node, including PV array, wind turbine, ESS, and load cluster.

-

Edges: Edges denote some physical or operational relationships (e.g., PV–ESS interconnection, ESS–load dependency, grid–DER link). The adjacency matrix ‘A’ encodes these dependencies.

Node features: At every time step ‘t’, each node is represented by a feature vector.

Learning task: The GENN learns to predict next-step values of renewable generation and demand, which are finally fed into the POA optimizer for resource scheduling.

Ensemble strategy: To reduce forecasting variance and improve generalization, several base GNN models are trained (Graph Convolutional Networks having identical architectures but with different initialization seeds). The average of all the base predictions becomes the final prediction.

The initial process begins with feature aggregation and normalization using a transformation step designed to refine the data input and enhance the predictive performance of the GENN for energy forecasting:

Where, \(\:{E}^{\left(k\right)}\) represents the optimized feature set for forecasting renewable energy output, grid load variations, and lighting system demands, \(\:A\) represents the connectivity between distributed energy nodes, \(\:D\) is a scaling coefficient adjusting input importance, \(\:{M}^{\left(k\right)}\) is a learnable weight matrix that adapts to operational changes, and \(\:\beta\:\) represents an activation function that boosts forecasting precision under fluctuating energy profiles.

Next, each energy node, whether representing a PV input, storage units, or load demands, updates its forecast using contextual signals from neighboring elements:

Here, \(\:{e}_{v}^{\left(k\right)}\) represents the updated forecast for node \(\:v\), reflecting generation or demand, \(\:S\left(v\right)\) indicates the set of adjacent nodes influencing the prediction, \(\:{M}^{\left(k\right)}\) is a dynamic matrix controlling influence strength, and \(\:\beta\:\) represents an activation function improving prediction accuracy.

To stabilize the forecasting output, results from multiple models are averaged, minimizing inconsistency in power distribution strategies:

Where, \(\:\widehat{x}\) represents the aggregated energy forecast, encompassing PV generation and lighting demand, \(\:N\) denotes the total number of forecasts in the ensemble, and \(\:{f}_{n}\left(Y\right)\) indicates the individual prediction from the \(\:{n}^{th}\) model.

Forecasting precision is refined using a loss function that measures the error between predicted and actual values:

Here, \(\:L\) quantifies the deviation, \(\:{x}_{j}\) represents observed energy behavior of generation or consumption, and \(\:{\widehat{x}}_{j}\) indicates the predicted counterpart. A lower loss function value reflects improved decision-making for adaptive energy scheduling.

A regularization term is introduced to maintain model robustness and prevent overfitting during long-term learning:

Here, \(\:\lambda\:\) is the regularization weight, maintaining model generalizability and \(\:{\parallel{M}^{\left(k\right)}\parallel}^{2}\) represents the set of learnable parameters within the GENN framework.

By integrating this GENN-driven forecasting structure, the system achieves high precision in predicting PV generation and lighting system energy consumption patterns, ultimately enhancing energy sharing efficiency and operational stability for sustainable smart cities. The GENN was trained using MSE loss with an Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001, batch size = 64). Training consisted of 100 epochs with early stopping triggered if no improvement was seen for 10 epochs. The GENN then feeds into POA, providing better-informed inputs based on accurate forecasts of renewable availability and load demand in a graph structure that reflects actual DER interconnections. This allows the optimizer to schedule resources in a cost-minimizing yet efficient manner, keeping in mind the stochastic variations of renewable energy.

Traditionally, a GNN can capture the spatial dependencies between distributed energy resources, but being a single model with initialization and training data sensitivity, it suffers from overfitting or under-generalization in highly dynamic renewable environments. On the other hand, ensemble RNNs best learn temporal dependencies, but they treat DERs as independent time series without any consideration for their graph-structured interconnections (e.g., the PV–ESS, WT–load relationships). The proposed model combines theadvantages from the two: through graph convolutional layers, it encodes structural dependencies of the smart city energy system while the ensemble reduces variance across base learners, thereby achieving more stable forecasting than does a single GNN. Offered by GENN over RNN ensembles is greater adaptiveness to spatial–temporal variability, which is a necessity for energy forecasting.

In the reason for integrating POA with GENN lies in their complementary strengths and weaknesses. POA, when termed as a metaheuristic optimizer, is best for searching the decision space when it is highly complex, while also attempting to treat several constraints. But since the erroneous forecasts are used as inputs, POA performs very poorly, because the optimization leads to suboptimal scheduling that increases cost on a poor forecast. GENN, on the other hand, learns nonlinear temporal–spatial patterns in renewable and demand data and can forecast more accurately than a single model predictor. But, without being coupled with another tool, GENN cannot impose system constraints or optimize scheduling decisions. Thus, GENN decreases the uncertainty in the input to POA, and POA takes the forecast information from GENN and produces an optimal energy allocation that is compliant with the constraints. This synergy ensures that the proposed POA-GENN framework is aware of environmental variability and acts on it with cost-minimizing control actions and therefore outperforms the standalone approach of forecasting or optimization.

Result and discussion

This section presents the simulation outcome and the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The POA-GENN is introduced for EM of PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities. The proposed method, implemented using the MATLAB platform, is evaluated in comparison to several existing methods, including PSO-RNN, ANN, BSFAO, LSTM, and CCG-DNN.

All simulations were carried out using MATLAB R2023a on a workstation equipped with an Intel® Core™ i7-11700 CPU @ 2.50 GHz, 32 GB RAM, and Windows 10 (64-bit) operating system. The forecasting models (GENN and baseline neural models) were implemented using MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox, while optimization experiments (POA and baseline metaheuristics) were coded in MATLAB scripts. The simulation horizon covered a 24-hour operation cycle, with time steps of 1 h, and repeated across 30 independent runs with different random seeds to ensure statistical reliability. Load profiles were derived from typical smart lighting demand curves. For POA, the population size was set to 50, with a maximum of 200 iterations per run. GENN training was conducted with 128 hidden units, ReLU activation, Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001), batch size = 64, and trained for up to 100 epochs with early stopping (patience = 10). All other baseline algorithms were implemented under the same simulation platform with their recommended hyperparameters for a valid comparison.

Figure 3 illustrates the analysis of solar irradiance. The irradiance starts at 0 W/m² at the 6th hour and increases steadily, reaching a peak of approximately 1000 W/m² just before the 12th hour. After this peak, significant fluctuations are observed due to atmospheric variations, with irradiance dropping sharply to around 600 W/m² shortly after the 12th hour, then briefly rising near 900 W/m². During the time between the 14th and 16th hour, the light intensity oscillates between 300 and 50 W/m². By the 16th hour, the output decreases each minute and drops close to 0 W/m² by the 18th hour. The pattern of this shows that solar energy often varies greatly, affecting how efficiently PV-powered lighting systems operate. Midday peak and rapid drops indicate cloud transients/atmospheric variability typical of real weather time series. The mid-afternoon oscillations (300→50 W/m²) denote intermittent shading or speedily passing clouds. The GENN better predicts these sub-hour irradiance patterns than single-model predictors, GENN provides POA with a tighter prediction distribution (lower variance of forecast). This allows POA to cause pre-scheduling of battery charge/discharge so that the system will not operate only after irradiance has dropped. POA role include uses GENN forecast to advance charging when a sharp dip is predicted (wasting low PV energy) or to delay discharge when surplus is anticipated.

The PV current analysis is presented in Fig. 4. Starting from 0 A at the 6th hour, the current gradually increases, reaching a peak of approximately 10 A just before the 12th hour. Afterward, due to variable solar irradiance, the current exhibits fluctuations, sharply dropping to around 7 A shortly after the 12th hour and momentarily rising above 9 A before continuing to oscillate between 6 A and 8.5 A from the 13th to the 15th hour. As time progresses, a consistent decline is observed, with the current falling to around 5 A by the 16th hour and further reducing to 0 A by the 18th hour. Such a profile accurately shows the PV system’s reaction to how much sun it gets, which helps predict future power output and make PV-powered lighting systems more efficient. PV current is scaled by irradiance. Small transient peaks correspond to very fast irradiance changes and to quick reactions from MPPT/inverter. GENN predicts the future PV current (via irradiance forecast) so that POA may temporally shift ESS operation (charge when surplus is predicted; discharge when a drop is forecast).

Figure 5 depicts the battery current analysis. The battery starts to charge when the solar current is about 0 A at the 6th hour, and by about the 12th hour, the current is 10 A, showing that battery charging is efficient when peak sunlight is generated. Over the time period from 12 to 14th hours, the current moves between 7 A and 9.5 A, providing evidence that environmental factors are changing the solar irradiance. After the 14th hour, the current decreases steadily from approximately 9 A to 3 A by the 16th hour, followed by sharper declines and irregularities between 2 A and 4 A, eventually returning to 0 A at the 18th hour. This pattern reflects the dynamic energy flow and storage adjustments essential for the uninterrupted operation of lighting infrastructure in smart urban environments. Battery charges when there are a PV surplus and discharges as PV power decreases. These fluctuations reflect POA decisions responding to the ever-changing PV and load. Based on the forecast from GENN, POA can avoid rapid changes that would otherwise lead to a quick charge and discharging (which leads to cycling losses). Another trait is for POA to pre-charge to an intermediate SOC in anticipation of an expected drop, then discharge at a controlled rate in the low PV scenario, balancing load requirements with degradation.

The PV voltage analysis is shown in Fig. 6. At the 6th hour, the voltage sharply increases to above 40 V and then rapidly drops to approximately 36 V, indicating the transition from startup to stable generation. Between the 8th and 14th hours, the voltage remains relatively steady between 36 V and 37.5 V, corresponding to optimal solar energy harvesting during peak sunlight hours. From the 14th hour onward, the voltage shows a gradual decrease, reaching around 35 V by the 18th hour. This steady voltage trend demonstrates consistent PV output with minor variations, supporting a reliable power supply forlighting infrastructure throughout the daylight period. A narrow voltage band means good MPPT, and inverter control try to keep the operating point close to the PV maximum power region despite changes in irradiance. POA-GENN, however, does not directly control the PV voltage; it instead tries to alleviate load swings by adjusting ESS or inverter dispatch setpoints that would otherwise give rise to voltage transients.

Figure 7 shows the analysis of battery voltage. At the 6th hour, the battery voltage is approximately 35 V. It gradually increases, reaching a peak of about 36.8 V around the 12th to 13th hour, which corresponds to the time of highest solar irradiance and optimal PV charging. After this peak, the voltage slightly decreases, returning to around 34.5 V by the 18th hour. Throughout the day, the battery voltage remains within a stable range of 34.5 V to 36.8 V, indicating efficient EM and a well-regulated charging and discharging cycle suitable for a PV-powered lighting system in smart city environments. Voltage variations are linked to SOC and charge/discharge currents. A narrow band means a controlled charging process. POA able to prevent voltage extremes and keep charging well within the recommended range-again, show SOC band and not just current/voltage.

The analysis of PV active power is shown in Fig. 8. At the end of the 6th hour, the system has no power, but the power begins to grow steadily to about 300 W by the end of the 12th hour, representing the greatest solar energy at midday. After 12th hour, you can notice power output dropping to about 200 W, then going back up to just over 270 W by the 14th hour. This variation is likely due to intermittent shading or environmental changes affecting solar input. Following the 14th hour, the power gradually decreases with additional fluctuations, dropping to around 150 W at the 15th hour and further falling to approximately 80 W by the 16th hour. Finally, the output declines to 0 W at the 18th hour. This power trend aligns with typical solar generation patterns and highlights the importance of adaptive energy control in PV-powered lighting systems for smart urban infrastructure. A case for a PV active-power follows the irradiance; the short-time variability implies atmospheric transients. During short surpluses, POA-GENN shall charge the battery to convert PV energy from being wasted, while during short dips in the transient, it discharges (charge/discharge synergies with load to level net power delivered so that PV + battery behaves more constant).

Figure 9 illustrates the active power analysis of the battery. The battery starts at 0 W at the 6th hour, gradually increasing as the demand and system operation intensify. The power output peaks at around 300 W at the 12th hour, coinciding with maximum energy generation and load activity. Between the 12th and 14th hour, the graph shows multiple fluctuations, where the power drops to nearly 230 W and briefly rises to about 280 W, indicating dynamic charging and discharging actions in response to system load and PV availability. After the 14th hour, the battery power declines consistently, dropping to around 150 W by the 16th hour and further to 80 W after the 16th hour. By the 18th hour, the output returns to 0 W. This profile confirms the battery’s active role in balancing power supply during variable solar input and ensuring uninterrupted lighting functionality in smart city infrastructure. The battery charges/discharges concerning PV power surpluses and deficits. Peaks around mid-time refers heavy charging with abundant PV power and discharging whenever necessary. The scheduling of the POA application should minimize the volatility of battery power while providing the best means of meeting load. Expect HV-switching events to appear less with POA-GENN.

Figure 10 depicts the grid power analysis. At the 1 st hour, the power drawn from the grid surges to approximately 2000 W, followed by a sharp reversal at the 2nd hour, reaching nearly − 1000 W, indicating power being fed back to the grid. By the 3rd hour, the power spikes again to around 2200 W before declining to approximately 500 W by the 4th hour. Between the 4th and 5th hour, the power level hovers near 0 W, suggesting minimal grid interaction. At the 5th hour, the system starts drawing more power again, climbing to about 1500 W by the 6th hour. A brief fluctuation peaks near 2200 W at the 7th hour, after which the power stabilizes at around 2000 W and remains steady through to the 10th hour. These fluctuations reflect a dynamic power exchange pattern between the smart city’s lighting system and the grid, governed by load demands and the availability of solar and battery power throughout the day. The early swings from either direction imply system exports (negative sign) and at times-maybe due to mismatching between the generation pattern and the load or overcoming scheduled exchanges. These generations mean scheduling ESS with GENN forecast application in such a way that grid imports at peaks are lowered and exports are done only under economic efficiency.

The load power analysis is presented in Fig. 11. Initially, the load starts at 2000 W at the 0th hour, quickly rising to 2700 W, where it remains constant until around the 3rd hour. At the 4th hour, the load drops back to 2000 W, indicating a lower demand phase. However, at the 5th hour, the load again increases significantly to 2800 W, marking the highest demand level observed in the period. This peak lasts until the 6th hour, followed by a drop back to 2000 W. A short spike to 2600 W occurs at the 7th hour before it again settles at 2000 W, which remains consistent through to the 10th hour. These fluctuations reflect dynamic lighting and energy usage needs in a smart city environment, necessitating efficient load management strategies in coordination with grid and renewable energy inputs. Scheduling decisions are therefore the driver. Since load is quite deterministic (step changes), if one forecasts load with accuracy, POA can accordingly schedule battery dispatch. With GENN forecasting load and POA, anticipation of load peaks could lead to pre-charging or avoiding rapid draws from the grid.

Figure 12 shows the PV output power analysis. During the initial phase, between the 1 st and 2nd hour, the inverter power output fluctuates significantly, ranging from approximately 1000 W to 3500 W, indicating a transient operational behavior. Around the 2nd hour, the power output sharply increases and stabilizes near 3500 W, with noticeable high-frequency oscillations occurring between the 2nd and 6th hour, where the output varies slightly between 3300 W and 3800 W. These variations are likely caused by changes in solar irradiance and dynamic adjustments in the energy conversion process. From the 6th hour onward, the power output becomes steady at approximately 3500 W, indicating that the PV system has reached a consistent and efficient operating condition suitable for continuous energy supply to smart city lighting systems.

The PV reactive power analysis is shown in Fig. 13. Throughout the entire duration, the reactive power remains consistently close to 0 VAR, with only very small oscillations observed intermittently between the 1 st and 6th hour. These slight fluctuations vary within a narrow range of approximately − 100 VAR to + 100 VAR, indicating minimal reactive power exchange. From the 6th hour onward, the reactive power output fully stabilizes at 0 VAR, showing that the inverter is supplying active power only to the load. This steady behavior highlights the system’s efficient performance, making it well-suited for smart city lighting applications where reactive power compensation is not required. System operates at close to unity power factor (PF ~ 1) so power quality is good. POA-GENN is basically optimizing for active energy only; any reactive power management is done by the inverter control and is not within the scope of the POA-GENN.

Figure 14 illustrates the monthly analysis of average wind speed, separating natural wind and the additional wind generated by vehicle movement. In January, the total average wind speed is approximately 5.6 m/s, with natural wind contributing about 4.2 m/s and vehicle movement adding around 1.4 m/s. February shows a slight increase to about 5.8 m/s. The values continue to rise through March at 6.2 m/s and April at 6.2 m/s. May and June record further increases, reaching 6.2 m/s and 6.8 m/s, respectively. The peak occurs in July and August, both at approximately 6.9 m/s, where the contribution from vehicle movement is most prominent. A decline follows in September at 5.6 m/s and in October at the lowest value of 4.8 m/s. The wind speed begins to recover in November with 5.9 m/s and in December with 6.1 m/s. By forecasting wind speed, GENN allows POA to include wind forecast in the scheduling. Its impact, with regard to the given profiles, is smaller than PV but nonetheless contributes to cost and energy mix. This analysis highlights the potential for harnessing wind energy in urban environments, where both natural and vehicle-induced airflow can be effectively utilized to support renewable energy systems and improve the efficiency of urban infrastructure.

Table 3 compares the operational costs of various methods applied to the lighting system with PV-energy sharing management for sustainable smart cities. The PSO-RNN method incurs a cost of 525.37€ct, demonstrating moderate efficiency in balancing energy resources. The ANN approach achieves a lower cost of 438.16€ct, reflecting better adaptability to system dynamics. The BSFAO method results in a higher cost of 656.35€ct, indicating less effective energy tracking under varying conditions. The LSTM technique records 589.33€ct, showing reliable but comparatively costlier performance. The CCG-DNN strategy delivers 475.28€ct, offering an effective balance between device coordination and energy use. The proposed POA-GENN method outperforms all, achieving the lowest cost of 365.24€ct, confirming its effectiveness in enhancing operational efficiency for the lighting system with PV-energy sharing management in sustainable smart cities.

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of efficiency across various methods used in energy forecasting and management. The PSO-RNN method demonstrates high efficiency at 92.5%, showing strong capability in energy dispatch and prediction. The LSTM approach follows with 90.6%, showcasing effective forecasting for dynamic energy patterns. CCG-DNN performs with 86.3%, highlighting competent device coordination and energy scheduling. ANN achieves 81.4%, indicating moderate adaptability in handling environmental variations. BSFAO records the lowest efficiency at 76.1%, reflecting limited tracking performance under partial shading conditions. The proposed POA-GENN method surpasses all with an efficiency of 99.2%, confirming its superior ability to enhance performance in the lighting system with PV-energy sharing management for sustainable smart cities.

Table 5 presents the mean ± standard deviation and p-values of the two-tailed t-tests performed to determine whether the other methods significantly differ from the proposed POA–GENN. The results were applied to the test, with the methods applied through 30 independent runs and then subjected to statistical analysis. In all these cases, p-values were below 0.001, which means the reductions in operational cost and the efficiency gains were statistically significant. The results thus prove that POA–GENN’s great performance is not by coincidence but has real statistical validation. The higher efficiency of POA–GENN is due to complementary characteristics present both in POA and GENN.

Exploration–Exploitation Strength of POA: The POA mimics the perfume diffusion in nature, balancing intensification (exploitation) with diversification (exploration). This technique allows the algorithm to explore the solution area searching for local optima to avoid them and finally end up with globally optimal schedules for energy allocation. When compared with classical approaches such as PSO, BSFAO, or DDPG, POA is even better in keeping the system stable while consistently searching for low-cost solutions for smart city lighting systems.

Forecasting Robustness of GENN: GENN is an integration of graph learning methods with ensemble neural networks in forecasting temporal dynamics and spatial correlations of energy demand and renewable supply. While the ensemble reduces bias and variance, the graph structure captures the interconnection between lighting zones and distributed resources. Thus, GENN becomes more accurate and resilient than independent predictors such as ANN or LSTM.

Synergistic Integration: With demand and renewables generation forecasted accurately by GENN, POA then generates an optimized schedule for lighting. Consequently, GENN is able to keep its forecasts aligned with operational needs thanks to continual feedback from within this optimization–forecasting loop. Such closed-loop interaction makes POA–GENN able to adapt to uncertainty, minimize operational cost, and maximize efficiency. Now, these factors explain why POA–GENN delivers better results and demonstrated as a better solution for smart-city lighting, where cost-effectiveness, adaptability, and dependability are mandatory.

Discussion

Optimized EM in PV-powered lighting systems for smart cities is crucial due to the highly variable nature of solar irradiance, which rises from 0 W/m² at dawn to a peak near 1000 W/m² before noon, then fluctuates irregularly between 50 W/m² and 900 W/m² in the afternoon, before dropping back to zero by evening38. This variability directly affects the PV current, which increases from 0 A to around 10 A at peak sunlight, then oscillates between 6 A and 8.5 A during fluctuating irradiance periods, finally tapering off to zero. PV voltage remains relatively stable between 36 V and 37.5 V during peak hours, decreasing gradually afterward, and ensuring consistent power output. The battery system actively adapts to these changes, with charging currents reaching up to 10 A around midday and battery voltage peaking at about 36.8 V, then declining steadily, reflecting efficient charge-discharge cycles. Active power from the PV system and battery follows similar patterns, peaking around 300 W at noon and adjusting dynamically to fluctuating solar input and load demands. Grid power exchange shows significant variability, especially during early hours, indicating a responsive interaction between load, renewable sources, and storage. The load itself varies between 2000 W and 2800 W throughout the day, emphasizing the need for precise energy forecasting and management. The effectiveness of the proposed POA-GENN method is proven by its low operational cost of 365.24 €ct and its high energy efficiency of 99.2%, making it the best choice for PV-powered lighting systems in balancing cost reduction and performance in a sustainable smart city.

Conclusion

The proposed POA-GENN hybrid technique handles problems related to EM in PV-built lighting systems forsmart cities, since it integrates improved optimization and accurate forecasting methods. By combining the POA for optimal energy allocation and the GENN for precise prediction of energy generation and consumption, the method significantly improves system performance. Implemented and tested on MATLAB against existing approaches such as PSO-RNN and ANN, the POA-GENN technique demonstrated superior results with an operational cost of 365.24 €ct and an efficiency of 99.2%, compared to PSO-RNN, which had a cost of 525.37 €ct and an efficiency of 92.5%, and ANN, which had a cost of 438.16 €ct and an efficiency of 81.4%. This confirms that using this approach improves the sustainability and stability of linking renewables, lowers costs, and makes it appropriate for EM in smart city lighting systems.

Limitation

It is difficult for the proposed method to maintain its standard output when there is low solar radiation or poor access to wind, since it relies on variability in RES. Sometimes, when power is cut during these gaps, the system cannot operate properly, which is an issue for urban lighting.

Scalability: Currently, the implementation was validated for a moderate smart city lighting scenario. Since the framework, in principle, could be extended toward larger urban environments, with highly complex networks involving thousands of nodes, its performance has still not been fully tested. Future works should, therefore, concentrate on distributed or hierarchical implementations to guarantee seamless scalability.

Computational Complexity: The hybrid method combines optimization (POA) with forecasting (GENN) and thereby increases the computational load compared to one-model methods. Although simulation on the present hardware configuration yields acceptable runtime, algorithmic complexity may also increase disproportionately when dealing with larger datasets or finer scheduling horizons. Effective parallelization of POA and GENN and lighter versions of them will certainly help in alleviating such difficulty.

Real-Time Adaptability: The study mainly focused on the scheduling process in the day-ahead planning horizon and hourly interval. In contrast, real-world smart city lighting calls for quick response to last-minute changes, including the sudden demand surge, faults, or abrupt weather variations. Faster inference and optimization cycles in the real-time setup could be aided by edge computing and online learning methods.

By further considering this limitation, future opportunities to improve scalability, increase performance while lowering computational overhead, and achieve real-time adaptability for a practical large-scale installation are recognized.

Future work

It is possible for future work to involve more advanced predictions and regular changes to EM strategies in real time. Using extra energy methods such as solar-wind hybrid systems, vehicle-to-grid support, and peer-to-peer sharing improves the power grid’s reliability in every environment.

An IoT-based sensor and actuator network combined with POA–GENN framework integration would provide real-time monitoring and control of the smart lighting system. Such integration would thus maximize responsiveness and allow for dynamic adaptation to changing urban conditions. The optimization-forecasting cycle, integrated with digital twin models of urban infrastructure, can now be used to virtually test and validate lighting strategies before they are physically deployed. This method can reduce risk, enhance better decisions, and create a safe environment in which scenarios can be tested through analysis. Performing pilot studies in urban districts or smart campuses will yield insights into real-world issues such as communication latency, hardware limitations, and system interoperability. Pilot deployment would also allow stakeholders in validating both the technical feasibility of the framework and its socio-economic value.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Alternate Current

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- ABC:

-

Artificial Bee Colony

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- ARO:

-

Artificial Rabbits Optimizer

- AVOA:

-

African Vulture OptimizerAlgorithm

- BTS:

-

Base Transceiver Stations

- BSFAO:

-

Bird Swarm Fostered Aquila Optimization

- CCG:

-

Column-and‐Constraint Generation

- CMBO:

-

Cat and Mouse-Based Optimization

- DC:

-

Direct Current

- DI:

-

Discomfort Index

- DL:

-

Deep Learning

- DNN:

-

Deep Neural Network

- DSM:

-

Demand-Side Management

- DDPG:

-

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient

- DDPG-DRL:

-

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient-Deep Reinforcement Learning

- EM:

-

Energy Management

- EMA:

-

Evolutionary Mating Algorithm

- ESS:

-

Energy Storage Systems

- FFNN:

-

Fixed Forward Neural Network

- GA:

-

Genetic Algorithm

- GJO:

-

Golden Jackal Optimizer

- GNN:

-

Graph Neural Network

- GENN:

-

Graph Ensemble Neural Network

- IP:

-

Internet Protocol

- IEDS:

-

Integrated Energy Distribution System

- LCC:

-

Life Cycle Cost

- LSO:

-

Light Spectrum Optimizer

- LSTM:

-

Long Short-Term Memory

- MG:

-

Microgrid

- MPP:

-

Maximum Power Point

- MGEM:

-

Microgrid Energy Management

- MILP:

-

Mixed-Integer Linear Programming

- MPPT:

-

Maximum Power Point Tracking

- MQTT:

-

Message Queue Telemetry Transport Protocol

- MDDNN:

-

Matrix Diffractive Deep Neural Network

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- PAR:

-

Power Adequacy Ratio

- PDF:

-

Probability Density Function

- POA:

-

Perfumer Optimization Algorithm

- PSO:

-

Particle Swarm Optimization

- PCGAN:

-

Progressive Conditional Generative Adversarial Network

- PCSANN:

-

Pyramidal Convolution Shuffle Attention Neural Network

- RES:

-

Renewable Energy Sources

- RNN:

-

Recurrent Neural Network

- SAO:

-

Snow Ablation Optimization

- SOC:

-

State-of-Charge

- SCSO:

-

Sand Cat Swarm Optimization

- TCP:

-

Transmission Control Protocol

- vCANN:

-

Viscoelastic Constitutive Artificial Neural Network

- WT:

-

Wind Turbines

- \(Z_t^{ESS,u}\) :

-

ESS Input

- \(Z_t^{ESS,v}\) :

-

ESS Output

- \(Z_t^{ESS}\) :

-

Battery ESS Function

- t :

-

Time step

- \(t-1\) :

-

Previous Time Step

- \(\xi\) :

-

ESS Loss factor

- \(\omega_c\) :

-

Charging efficiency

- \(\omega_d\) :

-

Discharging efficiency

- \(Z_{max}^{ESS }\) :

-

Maximum Charging/Discharging Power

- \(R_{min}^{ES}\) :

-

ESS lowest remaining capacity

- \(R_{max}^{ES}\) :

-

ESS highest remaining capacity

- m :

-

Solar Irradiance

- \(\sigma^2\) :

-

Standard Deviation

- \(\beta\) :

-

Beta PDF

- \(P_a\) :

-

Rotor blade’s aerodynamic power

- \(P_v\) :

-

Kinetic power of the wind

- \(E_c\) :

-

Energy Coefficients

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Turbine tip speed ratio

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Blade pitch angle

- \(D_t\) :

-

WT’s blade area

- \(\rho\) :

-

WT’s air density

- \(v_t\) :

-

WT’s wind speed

- \(T_a\) :

-

Aerodynamic torque

- \(I^\prime\) :

-

Inverter current

- \(I_X,I_Y,I_Z\) :

-

Three-phase current

- \(w_{XZ},w_{YZ}\) :

-

Public grid voltages between three phases

- \(g_X,g_Y\) :

-

Inverter control variable

- \(\:h_X,h_Y,h_Z\) :

-

Sample voltages of the three phases

- \(w_{XZ}^\prime,w_{YZ}^\prime\) :

-

Output inverter voltages between three phases

- \(Z(t)\) :

-

System’s operational cost

- \(E_u^{S1}\) :

-

Updated operational cost value

- \(E_u^{S2}\) :

-

New fitness score

- \(Y_u^{S2}\) :

-

Refined energy allocation

References

Pandiyan, P. et al. Technological advancements toward smart energy management in smart cities. Energy Rep. 10, 648–677 (2023).

Mohamed, M. A. E. et al. Optimal energy management solutions using artificial intelligence techniques for photovoltaic empowered water desalination plants under cost function uncertainties. IEEE Access. 10, 93646–93658 (2022).

Dui, H., Lu, Y. & Xing, L. Optimizing power resilience performance of intelligent solar photovoltaic system for smart energy management considering reliability and cost. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 74 (3), 3071–3082 (2024).

Al Smadi, T. et al. Artificial intelligence control of energy management PV system. Results Control Optim. 14, 100343 (2024).

Şahin, M. E. & Blaabjerg, F. PV-powered hybrid energy storage system control using bidirectional and boost converters. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 49 (15), 1260–1277 (2022).

Rojek, I., Mikołajewski, D., Mroziński, A. & Macko, M. Machine learning-and artificial intelligence-derived prediction for home smart energy systems with PV installation and battery energy storage. Energies 16 (18), 6613 (2023).

Saleem, M. I., Saha, S., Izhar, U. & Ang, L. Optimized energy management of a solar battery microgrid: an economic approach towards voltage stability. J. Energy Storage. 90, 111876 (2024).

Chekira, O. et al. An improved microgrid energy management system based on a hybrid energy storage system using an ANN NARMA-L2 controller. J. Energy Storage. 98, 113096 (2024).

Behera, P. K. & Pattnaik, M. Supervisory power management scheme of a Laboratory-Scale Wind-PV-Based LVDC microgrid integrated with hybrid energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 60 (3), 4723–4735 (2024).

Guo, S., Ren, F., Wei, Z. & Zhai, X. A multi-objective collaborative planning method for a PV-powered hybrid energy system considering source-load matching. Energy. Conv. Manag. 316, 118848 (2024).

Sulaiman, M. H., Mustaffa, Z., Seyyedabbasi, A. & Irawan, A. Optimizing the deep learning parameters using metaheuristic algorithms for PV-battery-based DC nanogrids. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 45 (1), 2358068 (2024).

Gao, L. & Gao, Z. An optimal management architecture based on a digital twin for smart solar-based Islands incorporating deep learning and modified particle swarm optimization. Sol. Energy. 262, 111872 (2023).

Afroosheh, S., Esapour, K., Khorram-Nia, R. & Karimi, M. Reinforcement learning layout‐based optimal energy management in smart home: AI‐based approach. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18 (15), 2509–2520 (2024).

Eltawil, M. A., Mohammed, M. & Alqahtani, N. M. Developing machine learning-based intelligent control system for performance optimization of solar PV-powered refrigerators. Sustainability 15 (8), 6911 (2023).

Mendhe, N. & Vidyarthi, A. An effective hybrid approach-based control for the MPPT of PV systems under partial shading conditions for indoor energy harvesting in smart homes. Multimedia Tools Appl. 82 (30), 46717–46740 (2023).

Beniwal, R., Kalra, S., SinghBeniwal, N. & Gupta, H. O. Smart photovoltaic system for Indian smart cities: a cost analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (15), 45445–45454 (2023).

Arun, M. et al. Deep learning-enabled integration of renewable energy sources through photovoltaics in buildings. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 61, 105115 (2024).

Alhasnawi, B. N., Zanker, M. & Bureš, V. A smart electricity markets for a decarbonized microgrid system. Electr. Eng. 107 (5), 5405–5425 (2025).

Alhasnawi, B. N., Jasim, B. H., Sedhom, B. E. & Guerrero, J. M. A new communication platform for smart EMS using a mixed-integer-linear-programming. Energ. Syst. 16 (2), 471–488 (2025).

Suresh, B., Lakshmiprabha, K. E., Kumar, U. A. & Natraj, N. A. Battery integration and grid-connected hybrid power plant with an optimal energy management system integrated into a multilevel configuration. J. Energy Storage. 121, 116514 (2025).

Aurangzeb, M. et al. A novel hybrid approach for power quality improvement in a Vehicle-to‐Grid setup using Droop‐ANN model. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023 (1), 7786928 (2023).

Rangasamy, S., Prakash, S. A., Sakhare, N. N. & Kumar, U. A. Multiple microgrids with electric vehicle charging in a hybrid GJO-PCGAN approach for energy management. Electr. Eng. 107, 7523–7537 (2025).

Bhoopathi, M., Papana, V. P., Reddy, C. V. K. & Kumar, U. A. Unbalanced operation of integrated power distribution system for optimal energy flow using LSO-vCANNs approach. Environment Dev. Sustainability, 13, 1–25 (2024).

Alshboul, S., Abuelrub, A., Al-Masri, H. M. & Al-Shetwi, A. Q. Reliability-Driven optimization of hybrid renewable systems: assessing capacity and cost credits. Smart Grids Sustainable Energy. 10 (56), 1–25 (2025).

Momani, R. Q., Abuelrub, A., Al-Masri, H. M. & Al-Shetwi, A. Q. Cost-optimal sizing of battery energy storage systems in microgrids using artificial rabbits optimization. Energy Nexus. 19, 100486 (2025).

Alhasnawi, B. N., Hashim, H. K., Zanker, M. & Bureš, V. The rising, applications, challenges, and future prospects of energy in smart grids and smart cities systems. Energy Convers. Management: X. 27, 101162 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Physical-model-free intelligent energy management for a grid-connected hybrid wind-microturbine-PV-EV energy system via deep reinforcement learning approach. Renew. Energy. 200, 433–448 (2022).

Alzahrani, A. et al. A strategy for multi-objective energy optimization in smart grid considering renewable energy and batteries energy storage system. IEEE Access. 11, 33872–33886 (2023).

Laghridat, H., Essadki, A., Annoukoubi, M. & Nasser, T. A novel adaptive active disturbance rejection control strategy to improve the stability and robustness for a wind turbine using a doubly fed induction generator. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020 (1), 9847628 (2020).

Wang, D., Locment, F. & Sechilariu, M. Modelling, simulation, and management strategy of an electric vehicle charging station based on a DC microgrid. Appl. Sci. 10(6), 2053 (2020).

Hamadneh, T. et al. Perfumer Optimization Algorithm: A Novel Human-Inspired Metaheuristic for Solving Optimization Tasks. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering and Systems 18(4), 1–11 (2025).

Duan, R., Yan, C., Wang, J. & Jiang, C. Graph ensemble neural network. Inform. Fusion. 110, 102461 (2024).

Rauf, H., Khan, H. A., Khalid, M., Arshad, N. & Pecht, M. Reliability and economic assessment of integrated distributed hybrid generation and battery storage for base transceiver stations in intermittent utility grids. IEEE Access. 13, 121799–121814 (2025).

Zhu, Z., Weng, Z. & Zheng, H. Optimal operation of a microgrid with hydrogen storage based on deep reinforcement learning. Electronics 11 (2), 196 (2022).

Li, Y., Wu, J. & Pan, Y. Deep reinforcement learning for online scheduling of photovoltaic systems with battery energy storage systems. Intell. Converged Networks. 5 (1), 28–41 (2024).

Moosavi, M., Olamaei, J. & Shourkaei, H. M. Optimizing microgrid performance a multi-objective strategy for integrated energy management with hybrid sources and demand response. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 17827 (2025).

Chen, B., Li, Z., Liu, B., Fan, H. & Zhong, Q. Robust optimization for smart demand side management in microgrids using robotic process automation and grey Wolf optimization. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 19440 (2025).