Abstract

Cephalomedullary nail (CMN) is an ideal internal implant for the treatment of Basicervical femoral neck fracture (BFNF). This study uses finite element analysis techniques to compare the biomechanical characteristics of three types of CMN systems, namely proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) InterTAN and proximal femur bionic nail (PFBN), in fixing BFNF using three cannulated screws (CSs) as controls, and analyzed their clinical significance. Based on femoral CT and internal implant data, a finite element analysis model for BFNF internal fixation was established: CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN. The three types of loads, namely one-legged stance, torsion the femoral head, and walking, were simulated based on reference literature to obtain extreme values and cloud maps of data, including stress on fracture fragments and internal fixation devices, pressure between fracture surfaces, separation displacement, and sliding displacement. The biomechanical characteristics of different internal fixation devices were compared and analyzed. The finite element analysis data showed that in the one-legged stance group, the stress between the InterTAN fracture block and the internal fixation device, the extreme value of the pressure and sliding displacement between the fracture surfaces were lower than those of the other three models; In the femoral head torsion group, InterTAN had lower extreme values for both femoral head torsion displacement and fracture surface sliding displacement. The extreme values of separation displacement are second only to PFBN. In the walking exercise group, the extreme values of all indicators in InterTAN were lower than those in other models. Compared with PFNA and PFBN, InterTAN has better anti rotation ability and anti-inversion deformity ability, can provide better stability and safety, and provide guarantees for early functional exercise. This study provides clinical reference significance for the use of InterTAN in the treatment of BFNF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hip Joint Fractures (HJFs) have a high incidence and are a common type of fracture. Hip Joint Fractures (HJFs) have a high incidence and are a common type of fracture. According to research statistics, over 250,000 people experience HJF each year, and this amount will double by 20501. At the same time, the mortality rate of HJF is also high, resulting in an average reduction of 2.7% in patient life expectancy2,3. Therefore, HJF is not only a serious threat to the quality of life and safety of patients, but also a huge burden on social medical security resources. Therefore, HJF is known as the “last fracture of life”4.

Basicervical Femoral Neck Fracture (BFNF) is a rare type of HJF, accounting for approximately 0.74% −4.5% of HJF cases5,6,7. The definition and treatment methods have long been controversial. Early scholars believed that the fracture line of BFNF ran at the junction of the trochanter and the base of the femoral neck, and was therefore considered an intermediate state between Femoral Neck Fractures (FNF) and Inter-trochanteric Fractures (ITF)8. Due to this unique anatomical feature, BFNF exhibits both lateral instability of femoral ITF and rotational instability of head and neck of FNF9. The dual instability of BFNF not only leads to difficulties in fracture reduction and internal fixation, but also increases the risk of postoperative internal fixation failure. Therefore, choosing reliable and sturdy Internal Fixation Devices (IFD) is of great significance for reducing postoperative complications and improving patients’ quality of life.

Based on previous research, several scholars have suggested using implants for the treatment of femoral ITF to treat BFNF7,10. At present, Cephalomedullary Nail (CMN) is the main treatment for femoral ITF, which can effectively disperse the stress of weight load and conform to better biomechanical structure. Meanwhile, CMN also has the advantages of minimal invasiveness, short hospitalization time, and low blood loss11,12,13. In addition, Intramedullary Nail (IMN) fixation belongs to elastic fixation. There is research confirming that micro movements (displacement less than 0.5 mm) between fracture ends can cause greater osteogenic effects than bone resorption, promoting bone healing14. Clinical studies have shown that CMN has satisfactory efficacy in treating BFNF7,15.

In current clinical applications, representative CMNs include: single screw derotation cephalomedullary nail such as Proximal Femoral Nail Antirotation (PFNA), twin interlocking derotation and compression screw cephalomedullary nail such as InterTAN, and Proximal Femoral Bionic Nail (PFBN) etc. At present, there is still a lack of biomechanical evidence on which type of CMN has more advantages. The purpose is to use Finite Element Analysis (FEA) techniques to compare the efficacy of three CMN systems, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN, in treating BFNF with fixed Cannulated Screws (CSs) as controls (assuming that PFBN will exhibit superior biomechanical properties). The second objective is to provide new ideas for the treatment of BFNF.

Method

Establishment of the FEA models

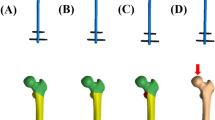

The experiment recruited a male volunteer who is 25 years old, 175 cm tall, and weighs 70 kg. The volunteer underwent a detailed and comprehensive physical examination by orthopedic doctors at The Third Bethune Hospital of Jilin University. A history of lower limb injuries and deformities, as well as related endocrine and immune system diseases that may affect bone metabolism, have been excluded. The volunteers were informed of the relevant risks and signed an informed consent form for the experiment. He underwent a left femur full length 3D CT scan at the radiology department of the hospital to obtain complete femoral DICOM data. After importing the data into Mimics Medical 21.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium software), a 3D model was created. Then, Geomagic Wrap 2021 software (Geomagic Company, USA) was used to further process the model, saved in STP format, and imported into SolidWorks 2023 (Dassault Systemes, USA). To obtain more accurate calculation results, the author manually segmented the model into distal Trabecular Bone (TB), proximal TB, and Cortical Bone (CB) parts using SolidWorks 2023 software. Due to anatomical differences, the thickness of CB altered in various regions. In this paper, the cortical thickness ranged from 7.0 mm (femoral shaft) to 1.0 mm (femoral head). Based on the fracture characteristics of AO/OTA 31-B3 in the 2018 version, the model was segmented16. Due to the fact that this study only involves the proximal femur, to reduce the pressure of FEA calculations, segmentation instructions were used to preserve only the proximal femur model and save it in part format (Fig. 1).

The models of CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN were constructed in SolidWorks 2023 based on data provided by the manufacturer. This study utilized rotation and translation functions in the assembly function module of SolidWorks 2023 software to adjust the IMN position to be consistent with the fixed position of the surgery (Fig. 2).

Material properties

The material properties of each component in the model were considered to be linearly elastic isotropic. Referring to previous studies, the properties of CB, TB, and titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4 V alloy) materials were obtained separately17,18,19,20,21. The data were imported into AnsysWorkbench, assigning material attributes to the corresponding entities (Table 1).

Boundary

Referring to previous research22,23, the following settings were made for the contact relationship of the model. The contact relationship between CB and TB on the same side of the fracture was set as binding. The contact mode between fracture surfaces, bone tissue and IFD, was set to friction, with a Friction Coefficient (FC) of 0.46 and FC = 0.3. The contact relationships between IFD components, such as the tension screws and compression screws of InterTAN, the tension screws and support screws of PFBN, the tension screws and main screws of PFBN, and the contact relationships between the main screws and distal locking screws of each IMN, were set to friction with FC = 0.23. Table 2 specifically shows each contact relationship.

To simulate the intraoperative locking state between the CMN and the main nail, the contact relationship between the two is set as binding, including: the spiral blade of PFNA and the main nail, the tension screw of InterTAN and the main nail, the compression screw of InterTAN and the main nail, the support screw of PFBN and the main nail, and the tension screw of PFBN and the main nail.

Loading conditions

According to previous research reports, the load stress during Two-legged stance, One-legged stance (OneLS), up and down stairs, and normal walking was 100% −140%, 232% −369%, 227% −316%, and 211% −285% of body weight24. To compare the efficacy of different IFD treatments for BFNF, this study selected three different load conditions: OneLS, torsion of femoral head (torsion), and walking exercise (Walking), to test the ability of IFD to resist fracture inversion instability and rotation instability, as well as to simulate the mechanical changes of fractures and IFD during postoperative functional exercise in patients. According to the reference, three sets of loads were set as follows1: OneLS group (OneLS-G): a vertical load of 300% body weight on the femoral head, which is 2100 N, with hip adduction of 12° and flexion of 10°25, and restrictions on movement in various directions are set on the mid section of the femur2; Torsion-G group: The torque of the femoral head is set to 15 N•m8,26, with restrictions on movement in various directions set in the mid section of the femur and behind the proximal end of the distal fracture fragment3; Walking group (Walking-G): The femoral head is loaded vertically at 250% of body weight, i.e. 1750 N, with hip joint adduction of 10°, flexion of 20°, and external rotation of 15°24. Restrictions on movement are set in various directions at the mid section of the femur. The above load is set at the weight-bearing area of the hip socket on the femoral head. The constraints and loads are shown in Fig. 3.

Meshing

A mesh convergence analysis was initially conducted by discretizing four models with tetrahedral elements. The convergence study employed a baseline mesh size of 4 mm, with convergence criteria defined as numerical variations of less than 5%27 and absence of localized stress concentration points. The final determined mesh size was 2 mm. To emphasize the mechanical behavior of the implant in specific regions of interest, all implant components were meshed with a refined element size of 1 mm, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

After gridding, the number of fixed model nodes and elements in each BFNF is shown in Table 3:

Observation index

ANSYS software was used to output stress cloud maps of implant and proximal fracture fragments under different loads. The “contact tool” function module was applied to output the sliding displacement, separation displacement, and pressure cloud map between fracture surfaces. For Torsion-G, the Displacement function module was used to output the femoral head displacement cloud map.

Finite element models validation

To clarify the reliability of the research model, the complete femur model was imported into ANSYS and assigned corresponding material parameters such as elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and density to CB and TB. The contact method was binding. The model remained fixed at the distal end and a vertical downward load of 2000 N was applied to the weight-bearing area of the femoral head. The maximum displacement of the femoral head in both horizontal and vertical directions was − 4.6117 mm and − 4.8708 mm. The strain range of the pressure side and tension side of the femoral neck was 6071.5–1108.6 μm/m and 3983.4–1080 μm/m. This is consistent with the biomechanical study and FEA results of femoral specimens in Daniel Kluess’ research28, proving the reliability of the research model. Based on previous studies29,30, the mid - shaft of the femur was fixed, and the same vertical load was applied to the femoral head. The output cloud map indicates that stress is concentrated on the medial surface of the femur, particularly at the femoral calcar. This finding is consistent with the physical structure of the femur and previous stress studies29,30,31,32,33,34, which once again validates the effectiveness of the model in this study.

Result

OneLS-G

IFD stress

Figure 5 shows the stress distribution of four internal implants in OneLS-G. CSs fixed group: The Maximum Stress Value (MSV) of the internal implants is 334.96 MPa, and the stress is centralized in the middle of the three CSs. The MSV of implants in the PFNA fixed group is 381.78 MPa, located at the intersection of the spiral blade and the main nail. The MSVs of the internal implants in the InterTAN and PFBN fixed groups after being loaded were 318.94 MPa and 355.22 MPa, respectively, located at the intersection of the compression screw and the main screw, and at the intersection of the tension screw and the support screw.

The stress of the proximal fracture fragment was concentrated on the pressure side fracture surface: the stress extremes of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups were 153.35 MPa, 95.734 MPa, 61.344 MPa, and 100.91 MPa (Fig. 6).

The extreme pressure values between fracture surfaces were concentrated on the fracture surface of the CB on the proximal pressure side of the femur: the extreme pressure values of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN fixation groups were 96.89 MPa, 56.482 MPa, 35.518 MPa, and 59.913 MPa (Fig. 7).

Sliding displacement and separation displacement between fracture surfaces.

In Fig. 8, after being loaded, the maximum sliding displacement between fracture surfaces was located on the pressure side cortical fracture surface. The maximum sliding displacement of each group of CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN was 0.24832 mm, 0.17585 mm, 0.14413 mm, and 0.16612 mm (Fig. 8).

In Fig. 9, after being subjected to load, the maximum separation displacement between fracture surfaces was located on the tension side cortical fracture surface. The maximum separation gaps of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups were 0.59364 mm, 0.27546 mm, 0.18349 mm, and 0.18079 mm. (Note: In the “gap” function module of this software, the separation distance is usually negative, and if there is no separation, it is 0)

Torsion-G

Femoral head torsion and displacement

The maximum displacement of the femoral head in the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups was 0.56839 mm, 0.5798 mm, 0.49534 mm, and 0.68545 mm (Fig. 10).

Sliding displacement and separation displacement between fracture surfaces.

The maximum sliding displacement between fracture surfaces in the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups was 0.14063 mm, 0.19789 mm, 0.132998 mm, and 0.288 mm (Fig. 11).

The maximum separation gaps between fracture surfaces in the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups were 0.18655 mm, 0.16095 mm, 0.1442 mm, and 0.13594 mm (Fig. 12).

Walking-G

Force analysis of implants stress

CSs group: the maximum stress of implants stress is 284.17 MPa, and the stress of the three CSs is concentrated in the middle; PFNA group: The maximum stress of implants stress is 311.39 MPa, located at the intersection of the spiral blade and the main nail; InterTAN group: The MSV of implants stress is 263.04 MPa, located at the junction of the distal locking nail and the main nail (Fig. 13).

The stress display of the two screws shows that the stress extremum is located at the thread engagement of the two screws, with a magnitude of 168.64 MPa. Stress concentration also occurs at the intersection of the two screws and the main screw (Fig. 14). PFBN group: The MSV of implants stress is 369.67 MPa, located at the intersection of the tension screw and the support screw in the middle.

Stress analysis of proximal fracture fragments

Under walking load, the stress of the proximal fracture fragment is concentrated near the fracture line on the pressure side of the femoral neck. The MSVs of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups are 108.4 MPa, 80.236 MPa, 38.172 MPa, and 80.524 MPa (Fig. 15).

Under walking load, the pressure between fracture surfaces is concentrated in the pressure side CB. The pressure extremes of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups are 45.176 MPa, 47.142 MPa, 18.046 MPa, and 31.249 MPa (Fig. 16).

Sliding displacement and separation displacement of fracture surface.

Under walking load, the maximum sliding displacement between fracture surfaces is located between the distal cortical fracture surfaces. The maximum sliding displacement of the CSs and PFNA groups is 0.24684 mm and 0.14789 mm. The maximum sliding displacement between fracture surfaces in the InterTAN and PFBN groups is 0.11097 mm and 0.18669 mm (Fig. 17).

Under walking load, the maximum displacement of fracture surface separation is located between the proximal cortical fracture surfaces. The maximum separation gaps of the CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN groups are 0.56677 mm, 0.23752 mm, 0.14474 mm, and 0.19866 mm (Fig. 18).

Discussion

HJF has become a serious threat to the safety of elderly people’s lives3. Due to its unclear definition and high failure rate of internal fixation, the treatment plan for BFNF has been controversial in the academic community9,35,36. When choosing internal fixation for the treatment of BFNF, the advantages of intramedullary fixation include smaller surgical incision, less intraoperative bleeding, and shorter surgical time37. It performs better than extramedullary fixation systems in terms of arm strength and resistance to bending and flexion, and can effectively prevent the occurrence of inversion. It has been highly sought after by many scholars15,36,38,39.

The Proximal Femoral Nail (PFN), also known as CMN, is characterized by: The cephalic or femoral head portion of the fixation construct is one or more screw or blade devices interlocked with the nail component of the construct. The paper targets to use FEA technology to compare and analyze the biomechanical performance of three different CMN systems, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN, under simulated loads of OneLS, Torsion, and Walking, in preventing inversion, preventing rotation, and assessing functional exercise, with CSs group as the control.

This study suggests that evaluating the performance of IFD mainly considers two aspects: stability and safety. Stability is manifested in the relative stability of the spatial anatomical relationship between fracture fragments after reduction by IFD, and the ability to reduce relative displacement between fracture fragments and prevent malunion when subjected to certain loads after surgery. The safety is demonstrated by the fact that the mechanical structure of IFD is less prone to stress concentration, which can lead to fracture failure; At the same time, it can effectively share the stress in the fracture block and change the stress distribution; Especially for elderly patients with osteoporosis, excessive stress concentration can lead to complications such as fracture collapse, inversion deformity, and IMN removal, preventing internal fixation failure. Although this study discusses stability and safety separately, the two characteristics complement each other, and high safety is a prerequisite for stability. High stability can create high security. The evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of internal fixation cannot be analyzed in isolation of two characteristics. This study evaluates stability by observing separation displacement, sliding displacement, and femoral head displacement between fracture surfaces, and evaluates safety by observing fracture block stress, internal implants stress, and fracture surface pressure.

According to literature40, when the peak stress of the titanium alloy internal fixation device reaches 450 MPa, it will lead to irreversible deformation of the titanium alloy internal fixation device. When the stress of the internal fixator is greater than 600 MPa, it will lead to the rupture of the internal fixator. However, our experimental results show that the stress of the implant does not reach the above-mentioned yield strength. Some studies have shown that41,42,43 the implant will be exposed to alternating stress for a long time, such as walking, even if the stress does not reach the yield strength, microscopic cracks will appear at the stress concentration and gradually expand, and finally rupture and internal fixation failure will occur. Therefore, it is important to reduce the value of stress concentration to improve the safety of the implant. With regard to micromovement at the fracture interface, the current consensus is that axial micromovement within an appropriate range can promote fracture healing14,44,45,46,47. In the internal fixation model of the basicervical fractures, the bone on the tension side and the pressure side are fractured. Therefore, the experimental output cloud chart can be observed: the extreme value of sliding displacement is on the pressure side, and the value of tension side is 0, and the value between the two changes step by step; The maximum value of the separation displacement is on the tension side, the value on the pressure side is 0, and the value between the two changes step by step. The shear forces generated during this period may adversely affect the regeneration of blood vessels and callus formation, resulting in delayed union44,45,48. In scenarios such as walking exercises, which impose multiple loads on the fracture site, unstable internal fixation can further impair fracture healing. Therefore, satisfactory internal fixation devices should reduce micromovement at the fracture interface.

CSs, as an internal fixation method for FNF, have shown good performance in combating rotational instability. However, its structure lacks the ability to resist varus deformity. In OneLS-G and Walking-G, although the extreme values of internal implants stress are lower compared to the other three CMNs, they are difficult to share bone stress and reduce pressure between fracture surfaces. At the same time, the maximum values of sliding displacement and separation displacement are higher than those of CMN, which cannot provide good inversion stability. It is not advisable to engage in functional exercise too early, as the risk of fracture malunion is high. In addition, its anti-rotation ability does not have a significant advantage compared to CMN in the torsion group. Another prospective study on BFNF49 compared CSs, DHS, and PFN, and found that although CSs have less soft tissue damage, less bleeding, and shorter surgical time, they have a higher risk of postoperative complications such as varus collapse, non-union of fractures, and screw breakage. Our study also demonstrated that CSs provided less fracture stability and took longer time for fracture healing. Scholar KIM’s research suggests that using blade type or double screw type CMN bone internal fixation to treat BFNF can significantly reduce the incidence of complications7. Therefore, it is not recommended to use CSs to treat young BFNF patients.

In CMN, InterTAN’s overall performance is significantly better than the other two CMNs. In OneLS-G and Walking-G, InterTAN can improve the stress distribution of fracture fragments and reduce the pressure between fracture surfaces. At the same time, the stress extremum of IFD is also low, and the risk of internal fixation failure caused by IFD fracture is also lower. In addition, InterTAN has shown good performance in controlling the separation displacement and sliding displacement between fracture fragments, indicating that it can provide good safety and inversion stability for BFNF fixation under these two loads. In the Torsion-G results, the model fixed by InterTAN has the lowest femoral head displacement value, sliding displacement extremum, and smaller separation displacement extremum, indicating that InterTAN can also provide good rotational stability. As a new type of CMN, the InterTAN head nail adopts a double screw design. During the insertion of the compression screw, the axial compression of the tension screw is driven by the interlocking thread between the compression screw and the tension screw. It converts anti-rotational stress into linear compression between the fracture ends, thereby enhancing the anti-shear performance of the screw and avoiding the “Z” effect. The design of double screws can hold more bone and achieve good stability. The double screw interlocking structure improves the stress distribution of IFD, avoids stress concentration, and ensures safety50,51,52. In our study, the contact relationship of the two head screws is set as binding, which mimics the effect of thread engagement as much as possible, but the compression effect of the fracture interface is simplified. Therefore, the actual clinical fixation effect may have higher stability and safety than the analysis results, such as smaller micromovement, smaller bone fragment and implant stress. Smaller fracture interface pressure and so on. However, there are currently few literature reports on the application of InterTAN in the treatment of BFNF, and further clinical evidence is needed for verification.

The head nail of PFNA is composed of only one spiral blade. The design of PFNA is to use impact force to drive the spiral blade into the cancellous bone and create a nail channel. This not only increases the contact area between the screw and the bone, but the compressed cancellous bone in reverse provides the anchoring effect of the spiral blade and provides higher resistance to rotation52,53,54. However, due to technical limitations, the model cannot simulate the compression effect of cancellous bone, so in reality, PFNA fixation may provide better stability and anti-rotation, resulting in less micromovement, pressure, and stress on the implant and bone at the fracture surface. Multiple studies suggest that PFNA has good efficacy in treating BFNF and can greatly reduce the fixed failure rate15,36,38,39. In this study, the safety and stability indicators of PFNA were not as good as InterTAN in all three experiments. A meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of PFNA and InterTAN in the treatment of unstable ITF suggests that the CMN InterTAN with dual screw integration is more effective in clinical practice, with fewer complications, fewer revisions, and fewer patients complaining of pain. However, the complex surgical procedures and prolonged operation time of InterTAN indirectly lead to an increase in intraoperative bleeding and fluoroscopy frequency55.

PFBN is a new type of CMN developed by the ZhangY team56. Its head nail is composed of double screws (Lag screw and Supporting screw) and forms a triangular stable structure with the main nail, theoretically possessing stronger biomechanical properties than PFNA and InterTAN. FEA has been used to compare the fixation effects of PFBN, DHS + DS, and PFNA on BFNF57, and it is believed that PFBN has better shear resistance and can improve mechanical properties. However, there were not many advantages demonstrated in the results of this experiment. Although PFBN and InterTAN, both CMN systems with two head nails, showed similar stability in all three experiments, the stress cloud maps of OneLS-G and Walking-G showed higher extreme values of implants stress in PFBN, which were concentrated at the cross locking point between the tension screw and the support screw. The performance of PFBN in sharing the stress of fracture fragments and reducing the pressure between fracture surfaces is not superior to InterTAN, and the value is similar to that of PFNA of single head nails, indicating that the safety is not high. The design of interlocking double headed nails can transfer stress between two screws and change the stress distribution. However, the difference between InterTAN and PFBN is that in the former, the two screws are locked by thread compression, and the stress transmission surface between the screws is wider and the stress is more dispersed. The two screws of the latter are interlocked at an angle, and the stress is concentrated in the intersecting parts, with higher and more concentrated stress. In addition, the CMN of double headed nails theoretically provides greater stability, but comes with greater trauma and more bone loss. Given the short clinical application time and lack of literature reports on the treatment of BFNF with PFBN, its efficacy needs further verification.

Limitation

This experiment used FEA to compare the biomechanical differences between CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN in treating BFNF. However, the femur model we used is from a healthy adult male and lacks certain applicability to elderly patients with femur deformation caused by underlying diseases such as osteoporosis. The bone and implants model used in the study are linearly elastic and isotropic, which cannot reflect the distribution of actual femoral bone mass and the detailed structure of bone and intervertebral disc. Moreover, the load applied in the experiment is relatively single compared to the actual clinical situation, and cannot evaluate the mechanical effects of soft tissues around the femur, such as muscle tissue, ligaments, periosteum, etc., on bone and fractures, thus having certain limitations. On the other hand, under normal physiological conditions, the force on the hip joint is not just a single load, but actually a combination of multiple loads that vary with different body postures and movement states. It is extremely hard to fully simulate the load on the femur under physiological conditions, especially dynamic loads like walking. Although this study set the contact relationship between models as friction and set the friction coefficient based on references, in actual clinical practice, the contact relationship between bone bone and bone ants stress is more complex. For example, special contact states such as tension screws that compress fracture fragments between fracture surfaces, PFNA spiral blades that compress and solidify osteoporotic bone, and interlocking threads between tension screws and compression screws in InterTAN are difficult to accurately simulate due to technical issues. Therefore, further biomechanical research and clinical trials are needed to draw more convincing conclusions.

Conclusion

In summary, the mechanical properties of CSs, PFNA, InterTAN, and PFBN in treating BFNF were studied through FEA. This study shows that compared with PFNA and PFBN, InterTAN has better anti rotation ability and anti inversion deformity ability, can provide better stability and safety, and provide guarantees for early functional exercise. This study provides clinical reference significance for the utilization of InterTAN in the BFNF treatment.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gullberg, B., Johnell, O. & Kanis, J. A. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 7 (5), 407–413 (1997).

Johnell, O. & Kanis, J. A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 15 (11), 897–902 (2004).

Papadimitriou, N. et al. Burden of hip fracture using disability-adjusted life-years: a pooled analysis of prospective cohorts in the CHANCES consortium. Lancet Public. Health. 2 (5), e239–e246 (2017).

Alexiou, K., Roushias, A., Varitimidis, S. & Malizos, K. Quality of life and psychological consequences in elderly patients after a hip fracture: a review. CIA 13, 143–150 (2018).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Surgical treatment of basicervical fractures of Femur—A prospective evaluation of 269 patients. J. Trauma: Injury Infect. Crit. Care. 64 (2), 427–429 (2008).

Guo, J. et al. Treatment of basicervical femoral neck fractures with proximal femoral nail antirotation. J. Int. Med. Res. 47 (9), 4333–4343 (2019).

Kim, J. T., Ha, Y. C., Park, C. H., Yoo, J. I. & Kim, T. Y. Single screw type of lag screw results higher reoperation rate in the osteosynthesis of basicervical hip fracture. J. Orthop. Sci. 25 (1), 152–155 (2020).

Blair, B., Koval, K. J., Kummer, F. & Zuckerman, J. D. Basicervical fractures of the proximal femur. A biomechanical study of 3 internal fixation techniques. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. (306), 256–263 (1994).

Yoo, J. I., Cha, Y., Kwak, J., Kim, H. Y. & Choy, W. S. Review on basicervical femoral neck fracture: Definition, Treatments, and failures. Hip Pelvis. 32 (4), 170 (2020).

Massoud, E. I. E. Fixation of basicervical and related fractures. Int. Orthop. 34 (4), 577–582 (2010).

Müller, F., Doblinger, M., Kottmann, T. & Füchtmeier, B. PFNA and DHS for AO/OTA 31-A2 fractures: radiographic measurements, morbidity and mortality. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 46 (5), 947–953 (2020).

Lewis, S. R., Macey, R., Gill, J. R., Parker, M. J. & Griffin, X. L. Cephalomedullary nails versus extramedullary implants for extracapsular hip fractures in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022 (1), CD000093 (2022).

Bartoníček, J. & Rammelt, S. The history of internal fixation of proximal femur fractures Ernst Pohl—the genius behind. Int. Orthop. (SICOT). 38 (11), 2421–2426 (2014).

Kenwright, J. & Gardner, T. Mechanical influences on tibial fracture healing. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 355S (355 Suppl), S179–S190 (1998).

Hu, S., Yu, G. & Zhang, S. Surgical treatment of basicervical intertrochanteric fractures of the proximal femur with cephalomeduallary hip nails. Orthop. Surg. 5 (2), 124–129 (2013).

Meinberg, E. G., Agel, J., Roberts, C. S., Karam, M. D. & Kellam, J. F. Fracture and dislocation classification Compendium-2018. J. Orthop. Trauma. 32 (Suppl 1), S1–170 (2018).

Ma, J., Zhao, Z., Zhi, X., Wang, H. & Wang, W. Finite element comparative analysis of three different internal fixation methods in the treatment of Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23 (1), 1030 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Titanium alloy gamma nail versus biodegradable magnesium alloy bionic gamma nail for treating intertrochanteric fractures: A finite element analysis. Orthop. Surg. 13 (5), 1513–1520 (2021).

Kim, J. W. et al. Structure-mechanical analysis of various fixation constructs for basicervical fractures of the proximal femur and clinical implications; finite element analysis. Injury 54 (2), 370–378 (2023).

Bernard, S. et al. Elasticity-density and viscoelasticity-density relationships at the tibia mid-diaphysis assessed from resonant ultrasound spectroscopy measurements. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 15 (1), 97–109 (2016).

Furui, A. et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the femoral neck system in unstable Pauwels III femoral neck fractures: A comparison with the dynamic hip screw and cannulated screws. J. Orthop. Trauma. 31 (3), 131–137 (2017).

Eberle, S., Gerber, C., von Oldenburg, G., Högel, F. & Augat, P. A Biomechanical evaluation of orthopaedic implants for hip fractures by finite element analysis and In-Vitro tests. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 224 (10), 1141–1152 (2010).

Nuño, N., Amabili, M., Groppetti, R. & Rossi, A. Static coefficient of friction between Ti-6Al‐4V and PMMA for cemented hip and knee implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 59 (1), 191–200 (2002).

Mu, J. X., Xiang, S. Y., Ma, Q. Y. & Gu, H. L. Selection of internal fixation method for femoral intertrochanteric fractures using a finite element method. World J. Clin. Cases 9 (22), 6343–6356 (2021).

Teng, Y., Zhang, Y. & Guo, C. Finite element analysis of femoral neck system in the treatment of Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture. Medicine 101 (28), e29450 (2022).

Ding, K. et al. Proximal femoral bionic nail—a novel internal fixation system for the treatment of femoral neck fractures: a finite element analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1297507 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Effects of different reduction patterns on stress distribution in patients with intertrochanteric fractures with intramedullary nail fixation: a finite element analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol [Internet]. 2025 Mar 12 [cited 2025 May 13];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2025.1507774/full

Kluess, D. et al. A round-robin finite element analysis of human femur mechanics between seven participating laboratories with experimental validation. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 10 (12), 1020–1031 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Establishing the 3-D finite element solid model of femurs in partial by volume rendering. Int. J. Surg. 11 (9), 930–934 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Finite element analysis of proximal femur bionic nail (PFBN) compared with proximal femoral nail antirotation and InterTan in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. Orthop. Surg. 14 (9), 2245–2255 (2022).

Yosibash, Z., Padan, R., Joskowicz, L. & Milgrom, C. A CT-Based High-Order Finite Element Analysis of the Human Proximal Femur Compared to In-vitro Experiments. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. June 1;129(3):297–309. (2007).

Zhang, Q. et al. The role of the Calcar femorale in stress distribution in the proximal femur. Orthop. Surg. 1 (4), 311–316 (2009).

Harty, M. The calcar femorale and the femoral neck. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 39-A (3), 625–630 (1957).

Hammer, A. The Calcar femorale: A new perspective. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong). 27 (2), 230949901984877 (2019).

Watson, S. T., Schaller, T. M., Tanner, S. L., Adams, J. D. & Jeray, K. J. Outcomes of Low-Energy Basicervical Proximal Femoral Fractures Treated with Cephalomedullary Fixation. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2016 July 6;98(13):1097–102.

Lee, Y. K. et al. Risk factors of fixation failure in basicervical femoral neck fracture: which device is optimal for fixation? Injury 49 (3), 691–696 (2018).

Kweon, S. H., Lee, S. H., Kook, S. H. & Choi, Y. C. Outcomes of cephalomedullary nailing in basicervical fracture. Hip Pelvis. 29 (4), 270 (2017).

Wang, Q. et al. Management of Low-Energy basicervical proximal femoral fractures by proximal femoral nail Anti‐Rotation. Orthop. Surg. 11 (6), 1173–1179 (2019).

Okano, I., Sawada, T., Kushima, N., Tachibana, T. & Inagaki, K. Treatment with helical blade cephalomedullary nail for Two-Part basicervical proximal femoral fracture in elderly patients: A retrospective observational study. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 8 (4), 244–251 (2017).

Vajgel, A. et al. Comparative finite element analysis of the Biomechanical stability of 2.0 fixation plates in atrophic mandibular fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 71 (2), 335–342 (2013).

Srivatsan, T. S., Soboyejo, W. O. & Lederich, R. J. The Cyclic fatigue and fracture behavior of a titanium alloy metal matrix composite. Eng. Fract. Mech. 52 (3), 467–491 (1995).

Fleck, C. & Eifler, D. Corrosion, fatigue and corrosion fatigue behaviour of metal implant materials, especially titanium alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 32 (6), 929–935 (2010).

Wu, Y. et al. Titanium Alloy Mater. Very High. Cycle Fatigue: Rev. Mater. ;17(12):2987. (2024).

Steiner, M., Claes, L., Ignatius, A., Simon, U. & Wehner, T. Disadvantages of interfragmentary shear on fracture healing–mechanical insights through numerical simulation. J. Orthop. Res. 32 (7), 865–872 (2014).

Elkins, J. et al. Motion predicts clinical callus formation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 98 (4), 276–284 (2016).

Vaughn, J. E. et al. Systematic review of dynamization vs exchange nailing for delayed/non-union femoral fractures. World J. Orthop. 9 (7), 92–99 (2022).

Shi, J., Xiao, Y., Wu, M. & Guan, J. Research on the nature of micromovement and the Biomechanical staging of fracture healing. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 35 (9), 1205–1211 (2021).

Loboa, E. G., Beaupré, G. S. & Carter, D. R. Mechanobiology of initial pseudarthrosis formation with oblique fractures. J. Orthop. Res. 19 (6), 1067–1072 (2001).

Sharma, A., Sethi, A. & Sharma, S. Comparative analysis of treatment of basicervical femur fractures in young adults with CCS, DHS, and PFN. Revista Brasileira De Ortop. (English Edition). 53 (6), 783–787 (2018).

Nüchtern, J. V. et al. Malpositioning of the lag screws by 1- or 2-screw nailing systems for Pertrochanteric femoral fractures: a Biomechanical comparison of gamma 3 and intertan. J. Orthop. Trauma. 28 (5), 276–282 (2014).

Hoffmann, S. et al. Biomechanical evaluation of interlocking lag screw design in intramedullary nailing of unstable pertrochanteric fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma. 27 (9), 483–490 (2013).

Wang, W., NI, B., Shen, H. & Lu, H. Meta-analysis of InterTan, PFNA and PFNA-II internal fixation for the treatment of unstable intertrochanteric fractures in elderly individuals. Acta Orthop. Belg. 89 (1), 51–58 (2023).

Frei, H. C., Hotz, T., Cadosch, D., Rudin, M. & Käch, K. Central head perforation, or cut through, caused by the helical blade of the proximal femoral nail antirotation. J. Orthop. Trauma. 26 (8), e102–e107 (2012).

Zhang, W., Antony Xavier, R. P., Decruz, J., Chen, Y. D. & Park, D. H. Risk factors for mechanical failure of intertrochanteric fractures after fixation with proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA II): a study in a Southeast Asian population. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 141 (4), 569–575 (2021).

Nherera, L., Trueman, P., Horner, A., Watson, T. & Johnstone, A. J. Comparison of a twin interlocking derotation and compression screw cephalomedullary nail (InterTAN) with a single screw derotation cephalomedullary nail (proximal femoral nail antirotation): a systematic review and meta-analysis for intertrochanteric fractures. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 13 (1), 46 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. Proximal femoral bionic nail (PFBN)—an innovative surgical method for unstable femoral intertrochanteric fractures. Int. Orthop. (SICOT). 47 (4), 1089–1099 (2023).

Cheng, X. et al. Finite element analysis of basicervical femoral neck fracture treated with proximal femoral bionic nail. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18 (1), 926 (2023).

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to all the authors for their assistance and backing during the data analysis and article composition stages.

Funding

This study was not supported by any fundings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. and X.C. : Conceptualization, Methodology, SoftwareC.C. and H.X. : Validation, Formal analysisZ.D. and F.C. : Data Curation, Writing - Original DraftG.H. : Writing - Review & EditingT.B. : VisualizationG.W. : Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The article lacks any research involving humans or animals conducted by its authors. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at The Third Bethune Hospital of Jilin University. Informed consent was acquired from all participants involved in the study. All procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Chen, X., Cao, C. et al. Finite element analysis of different cephalomedullary nail treatments for basicervical femoral neck fracture. Sci Rep 15, 40121 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23848-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23848-5