Abstract

In order to explore the evolution characteristics of mechanical and permeability properties of sandstone under real-time temperature conditions in deep geological environments, thermal-hydraulic-mechanical (THM) coupling tests were conducted on sandstone specimens at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 95 °C. The tests were performed using the Rock Top multi-field coupling tester to investigate the changes in strength, deformation, and permeability of the sandstone across the specified temperature range. Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to analyze the microstructure of the sandstone and its influence on mechanical properties. The results indicate that with increasing temperature, the strength of sandstone initially increases and then decreases, while the peak strain exhibits a rapid and nonlinear increase. Furthermore, the permeability of sandstone decreases initially and then increases as the temperature rises, demonstrating lower sensitivity to temperature variations compared to confining pressure. At various temperatures, the failure modes observed in sandstone consistently demonstrate typical shear slip characteristics. Moreover, at elevated temperatures, there is a significant increase in the number of cracks observed on the failure surface of sandstone. Under the action of lower temperature (25℃~65℃) the pores and micro-cracks of sandstone appear highly compact, and the new cracks are relatively few, but under the action of higher temperature (75℃~95℃), the size and number of defects in sandstone increase obviously, which is the fundamental factor that leads to the change of mechanical and permeability characteristics of sandstone. The research findings presented in this paper provide theoretical support for assessing the stability of surrounding rock in high geothermal tunnel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the deepening implementation of China’s “Belt and Road” initiative and the “Western Development” strategy, there has been a growing trend of deep underground space development in the western region1,2. The complex geological conditions and significant burial depth in deep underground areas often result in high ground stress and elevated seepage pressure environments. These conditions contribute to considerable rock deformation and pose significant engineering instability challenges in deep underground tunnels3. Additionally, the significant anomalies in geothermal activity in this region pose considerable challenges for the design, construction, and operation of deep-buried tunnels4. Therefore, conducting research on the mechanical properties, permeability characteristics, and microstructural evolution of sandstone under different real-time temperature conditions is of significant theoretical importance for the construction and operation of high-temperature tunnels in mountainous areas.

Currently, scholars both domestically and internationally have extensively researched the mechanical properties and permeability characteristics of rocks under thermal-hydro-mechanical (THM) coupling. This research includes investigations into the effects of THM coupling on rock strength5,6,7,8, acoustic properties9, and permeability10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For instance, Jiang et al.18. examined the mechanical properties of sandstone at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 100 °C, finding that the compressive strength and elastic modulus of sandstone decrease with increasing temperature, and post-peak deformation transitions from brittle to ductile behavior. Zhang et al.19. conducted permeability tests on red sandstone under different real-time temperature conditions, observing that the compressive strength of sandstone initially increases with temperature and then decreases. Zhang et al.20. and Lyu et al.21. studied the evolution of acoustic emission during the entire process of rock damage and failure under THM coupling, identifying a close correlation between acoustic emission ringing rate and rock damage deformation and fracture. Bu et al.22. found through experimental studies that the permeability of rocks under THM coupling decreases with increasing temperature. However, the aforementioned studies primarily focus on the mechanical and permeability properties of sandstone under THM coupling and do not deeply investigate the mechanism of thermal damage to rocks under THM coupling. Therefore, Wu et al.23. suggested that research on rock thermal damage should start from a microscopic level.

Methods used to determine the micro-damage characteristics of thermal damage in rocks mainly include scanning electron microscopy (SEM)24, nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMR)25,26 analyzers and micro-electron computed tomography (CT)27. Among these, SEM (scanning electron microscopy) has the advantages of a wide observation range and intuitive imaging, making it widely used in non-destructive detection of the microstructure inside rocks28,29. Zuo et al.30. used SEM to study the fracture morphology of sandstone under THM, revealing that the fracture mechanism of sandstone is influenced by a combination of intergranular fracture, trans granular fracture, and adhesive material fracture as temperature increases. Additionally, Meng et al.31. based on real-time high-temperature SEM images of sandstone, analyzed the trend of changes in microcracks during the temperature rise process, indicating that high temperatures lead to microstructural degradation and an increase in the permeability of sandstone. However, the aforementioned scholars have only focused on the macro-mechanical and permeability properties of sandstone or have been limited to the study of micro-thermal damage mechanisms. As a result, there is a lack of correlation between macro-mechanical properties, permeability characteristics, and microstructural evolution patterns.

The aforementioned research has made a lot of meaningful contributions to analyzing the mechanical properties of rocks and seepage patterns under thermohydraulic coupling. However, these studies have all examined seepage patterns under a single constant confining pressure, lacking insights into the evolution of rock seepage under varying confining pressure conditions. Furthermore, most research has focused on macroscopic mechanical properties. Therefore, this study employs the Rock Top multi-field coupling testing apparatus to analyze rock seepage characteristics at different temperatures through isogradient confining pressure increases. Simultaneously, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) techniques are utilized to investigate the microstructural evolution of sandstone under varying temperature conditions, revealing the interrelationship between macroscopic mechanical properties, permeability characteristics, and microstructural mechanisms.

Test principles and methods

Test rock samples and preparation

The sandstone used in the experiment was sourced from Sichuan Province. Following the requirements for standard specimen preparation, it was processed into a standard cylindrical shape with dimensions of 50 mm in diameter and 100 mm in height (Fig. 1). The flatness at both ends of the sandstone was maintained at less than 0.02 mm. Figure 2 shows the results of X-ray diffraction testing of the sandstone, revealing the predominant presence of three minerals: chlorite, sodium feldspar, and potassium feldspar, along with some quartz, muscovite, and calcite. Prior to the experiment, the sandstone was dried in a 105 °C oven for 24 h and then saturated in a vacuum saturation chamber32. Subsequently, the sandstone’s acoustic properties were tested using an ELB-UTD400 non-metal ultrasonic detector, with samples exhibiting abnormal wave velocities being discarded.

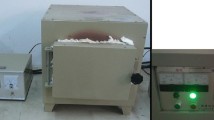

Test equipment

The equipment used in this experiment is the Rock Top multi-field coupling test system (Fig. 3). This equipment consists of axial compression, confining pressure, and permeation systems. The maximum applied axial stress is 500 MPa, the maximum applied confining pressure is 60 MPa, and the maximum applied upper and lower port pressures are 60 MPa and 50 MPa respectively, with a control precision of ± 0.01 MPa. The temperature control range is 20 °C to 150 °C with an accuracy of ± 0.5 °C. Internally, it is equipped with two LVDT displacement sensors (with a range of 12 mm and accuracy of 0.001 mm) and one radial strain sensor (with an accuracy of 0.001 mm and a resolution of 0.0001 mm).

Permeability test principle

The experiment employs the constant volume transient pressure pulse method to measure the variation of permeability of sandstone under different temperatures and confining pressures during cyclic loading and unloading states. The permeability expression used in this paper is based on the transient method and is as follows33:

Where: k is sandstone permeability (m2); \(\Delta {P_t}\) is upstream and downstream pressure difference measured value (MPa); \(\Delta {P_0}\) is initial pressure difference (MPa); \(\mu\) is fluid viscosity coefficient34 (At 25 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.8937 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 35 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.7225 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 45 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.5960 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 55 °C, the viscosity is µ = 0.5036 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 65 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.4325 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 75 °C, the viscosity is µ = 0.3765 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 85 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.3316 × 10−3 Pa·s; At 95 °C, the viscosity of water is µ = 0.2950 × 10−3 Pa·s); A is rock sample cross-sectional area (m2); L is water seepage length (m); t is time (s); \({C_1}\), \({C_2}\) are the water capacity of the upstream and downstream pressure vessels respectively; \(- \alpha\) is the slope of the semi-logarithmic pressure difference - time curve.

Test programs and test steps

To ensure the experiment remains unaffected by steam, this study sets the maximum temperature at 95 °C. The experimental temperature range is set from 25 °C to 95 °C, with increments of 10 °C, to simulate tunnel environments at burial depths of 100–2000 m3. Concurrently, the confining pressure was set at 30 megapascals to simulate in-situ stress conditions at a burial depth of 1,200 m, assuming an average rock density of 2.5 × 10³ kilograms per cubic metre35. The seepage pressure difference between the upstream and downstream ends of the rock is set at 0.2 MPa. The specific experimental protocols are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. The experimental procedure is as follows:

-

(1)

Install the sandstone into the triaxial pressure chamber, install the circumferential sensor and axial sensor in turn, and connect their seepage channels. Finally, perform an installation check.

-

(2)

After completing the oil filling of the confining pressure chamber, to prevent the saturated water in the sandstone from escaping due to a temperature rise, apply a confining pressure and maintain it at 5 MPa. Additionally, maintain the upstream and downstream seepage pressure difference at 0.2 MPa, raise the temperature of the stress chamber to the set value, and keep it stable for 12 h.

-

(3)

The perimeter pressure was gradually increased to 10 MPa using a stress loading rate of 1 MPa/min.

-

(4)

Under specified confining pressure conditions, both upstream and downstream seepage pressures were elevated to 5 MPa. Following a period of stabilisation, the downstream seepage pressure decreased to 4 MPa. Subsequently, the upstream and downstream pumps and their associated valves were shut off to create a sealed space, maintaining this state until internal pressure equilibrium was achieved within the sandstone. The permeability coefficient of the sandstone under these conditions was ultimately calculated using the fluid decay law.

-

(5)

Upon completion of the above step, the confining pressure was sequentially increased to 15, 20, 25, and 30 MPa at a loading rate of 0.2 MPa/min. Step 4 was then repeated to determine the permeability of the sandstone at the specified confining pressures. The specific experimental protocol is detailed in Table 1.

-

(6)

When step 5 was completed, the axial displacement was applied at a rate of 0.03 mm/min, and the stress and strain of the sandstone specimen were measured until its destruction occurred.The specific test protocol is detailed in Table 2.

Analysis of sandstone mechanical properties

Stress-strain curve

To facilitate the analysis of stress-strain curve results of sandstone at different temperatures, this study divides them into two groups: 25 °C to 55 °C, and 65 °C to 95 °C, as shown in Fig. 4. Experimental findings reveal that the overall shape of the sandstone stress-strain curve is significantly influenced by temperature and can be divided into five distinct stages: (I) compaction stage; (II) linear elastic stage; (III) stable crack propagation stage; (IV) unstable crack propagation stage; and (V) post-peak failure stage. In the 25 °C to 55 °C range, the stress-strain curve of sandstone exhibits characteristics of brittle fracture. After reaching peak strength, the load-bearing capacity rapidly declines, accompanied by post-peak residual stress. In the 65 °C to 95 °C range, the curve shows a pronounced pre-peak yielding stage and post-peak ductility, indicating reduced brittleness and increased ductility of sandstone after 65 °C. Additionally, compaction is more apparent at 95 °C, suggesting increased microcracks and porosity within the sandstone at higher temperatures, leading to decreased density.

Variations in peak strength, peak strain, and elastic modulus

In order to characterize the mechanical behavior depicted in the stress-strain curve, this study utilizes parameters including peak strength \(\sigma c\),peak strain \(\varepsilon c\),and elastic modulus \(Ec\) to evaluate the impact of temperature on the mechanical properties of sandstone. The calculated results are presented in Table 3.

Peak strength

Figure 5 illustrates the variation of peak strength of sandstone with temperature. The peak strength of sandstone shows an initial increase followed by a decrease with rising temperature. Compared to room temperature, as the temperature increases from 35 °C to 65 °C, the peak strength of sandstone increases by 1.43%, 3.23%, 5.92%, and 10.39%, respectively. This increase is primarily attributed to the thermal expansion of mineral grains within the sandstone at temperatures below 65 °C, leading to a reduction in distance between adjacent grains and gradual closure of internal primary fissures. As a result, the load-bearing capacity of the sandstone is enhanced. As the temperature rises from 65 °C to 95 °C, the peak strength of the sandstone gradually decreases. Relative to sandstone at 65 °C, its strength decreases by 4.94%, 8.76%, and 13.29%, respectively. This decrease is mainly due to the increased thermal stress on mineral grains, leading to the development of internal microcracks. Additionally, the erosive and lubricating effects of high-temperature water on mineral grains are intensified, thereby reducing the load-bearing capacity of the sandstone.

Peak strain

Figure 6 illustrates the variation of peak strain in sandstone with temperature. The results demonstrate a significant impact of temperature on the peak strain of sandstone. As the temperature rises, the peak strain of sandstone tends to decrease. At room temperature, the peak strain of sandstone is approximately 0.993%, which is almost the same as the peak strain at 35 °C, indicating minimal effect of lower temperatures on the peak strain of sandstone. However, as temperatures exceed 45 °C, the peak strain of sandstone gradually increases, with a more noticeable increase after 65 °C. This shift implies a transition of the sandstone from brittle failure to ductile failure.

Modulus of elasticity

Figure 7 illustrates the variation of the elastic modulus of sandstone with temperature. The study reveals a gradual decrease in the elastic modulus of sandstone with increasing temperature, presenting a distinct contrast to the pattern observed in peak strain with temperature. As the temperature increases from 35 °C to 65 °C, the elastic modulus of sandstone decreases by 4.41%, 7.01%, 10.69%, and 18.22%, respectively, compared to specimens at room temperature. This indicates relatively low damage within the sandstone at temperatures below 65 °C, attributed to the lower sensitivity of its elastic properties to temperature within this range. With temperatures rising above 65 °C, the elastic modulus of sandstone notably decreases, indicating significant internal damage and deterioration in its mechanical properties.

Test results on permeability characteristic of sandstone

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between sandstone permeability, temperature, and confining pressure. The magnitude of sandstone permeability ranges from 10−18 m2. As the confining pressure increases, the permeability of sandstone decreases nonlinearly. Particularly, under low confining pressure conditions, there is a significant reduction in permeability, while the rate of decrease lessens with further increases in confining pressure. For instance, at 95 °C, the permeability of sandstone decreases by 14.33%, 21.71%, 23.48%, and 24.13% with increasing confining pressure. This reduction is mainly due to the significant compaction effects of microcracks within the sandstone under lower confining pressures, which gradually weaken under higher confining pressures, leading to a reduced rate of permeability decrease. The permeability of sandstone initially decreases and then increases with temperature, in line with the findings of Li et al.31. At lower temperatures, the closure of primary fissures within the sandstone blocks effective flow channels, resulting in a relative decrease in permeability. At higher temperatures, thermal stress encourages the development of microcracks within the sandstone, increasing the number of effective flow channels. Effective flow channels can lead to a relative increase in permeability, similar to the mechanism observed in peak strength.

Additionally, Pearson correlation coefficients reveal the relationships between temperature, confining pressure, and permeability variables, as shown in Fig. 9. It is observed that the correlation coefficient between confining pressure and permeability is −0.71, while the correlation coefficient between temperature and permeability is −0.13, indicating that sandstone permeability is more sensitive to confining pressure than to temperature.

Characteristics of sandstone damage and internal mechanisms

Destruction patterns in sandstone

Figure 10 illustrates the failure modes of sandstone at different temperatures. The figure shows that the failure modes of sandstone under different temperature conditions are typically characterized by shear failure. At lower temperatures (25 °C to 65 °C), the failure mode of sandstone transitions from gradual-angle shear failure to steep-angle shear failure, with the fracture angle (angle between the failure plane and the horizontal direction) increasing continuously. At higher temperatures (75 °C to 95 °C), the predominant failure mode of sandstone is gradual-angle shear failure, with the fracture angle gradually decreasing. New fractures are evident on the surface of the sandstone between 85 °C and 95 °C, indicating that higher temperatures promote the development of microcracks in the sandstone and result in degradation of its macroscopic mechanical properties.

Microscopic failure characteristics analysis

Figure 11 depicts the microscopic characteristics of sandstone under different temperature conditions. In Fig. 11a, it can be observed that at room temperature, the internal structure of the sandstone consists of dispersed particles with numerous inherent microcracks and pores. The particles are primarily bonded through bridging. At this stage, the maximum width of cracks is only 2 μm. At temperatures ranging from 35 °C to 65 °C, thermal stress on the mineral particles induces thermal expansion, resulting in closer contact between particles and partial closure of inherent microcracks in the sample. As the temperature increases to 55 °C, the surface becomes uneven with more prominent edges, and the majority of microcracks have widths less than 1 μm. This phenomenon is a primary reason for the observed increase in peak strength and decrease in permeability of the sample. However, at 75 °C, the elevated thermal stress on sandstone particles leads to an increase in the number, length, and width of cracks. Mineral crystal structures are disrupted, evident by the presence of clear transgranular fractures. As the temperature exceeds 85 °C, the number of pores and cracks in the sandstone continues to expand, resulting in significant cracks penetrating the network. By 95 °C, the cracks have penetrated the crystal particles, and the surface microcrack width approaches 31 μm. Consequently, due to increased internal damage, the macroscopic mechanical behavior of the sandstone, such as peak strength and modulus, exhibits a decreasing trend, while permeability demonstrates an increasing trend.

Mechanisms of temperature, confining pressure, and pore water pressure on the microstrcture of sandstone

To further elucidate the impact of temperature, confining pressure, and pore water pressure on the microstructure of sandstone, Fig. 12 illustrates the mechanism of sandstone’s micromechanical behavior. Taking the microelement Y from the loaded specimen as the object, as shown in Fig. 12a, the microelement contains numerous inherent defects in its original state, such as intragranular cracks, intergranular cracks, and inherent pores, with free water filling the voids and cracks. At lower temperatures (25 °C to 65 °C), the mineral particles within the sandstone undergo thermal expansion, leading to a reduction in the distance between the particles. Additionally, the sandstone is constrained by confining pressure, further reducing the interparticle spacing, gradually closing the inherent cracks, and narrowing the permeable channels. From a macroscopic perspective, the peak strength of the sandstone increases, and the permeability decreases, as shown in Fig. 12b. At higher temperatures (75 °C to 95 °C), the mineral particles in the sandstone undergo uneven thermal expansion, generating significant thermal stresses and causing rapid propagation of intragranular and intergranular cracks. Furthermore, the erosive and lubricating effects of high-temperature water on mineral particles promote the softening of the sandstone and enhance its ductile failure. Consequently, the peak strength of the sandstone decreases, while the permeability relatively increases, as depicted in Fig. 12c.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of temperature and confining pressure variations on the mechanical properties and seepage characteristics of sandstone through a series of experiments. The principal conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

With increasing temperature, the peak strength of the sandstone initially increases and then decreases. Meanwhile, the peak strain shows a nonlinear rapid increase, while the elastic modulus exhibits an opposite trend.

-

(2)

The permeability of sandstone decreases with increasing confining pressure, while it exhibits a trend of initially decreasing and then increasing with rising temperature. The Pearson correlation coefficient between permeability and confining pressure is greater than that with temperature, indicating that the sensitivity of sandstone permeability to confining pressure is higher than to temperature.

-

(3)

Under different temperature conditions, the failure mode of sandstone manifests as shear failure. At lower temperatures, it transitions from a shallow dip angle shear failure to a steep dip angle shear failure. At higher temperatures, it exhibits a shallow dip angle shear failure, accompanied by a noticeable increase in associated cracks.

-

(4)

Increasing temperature promotes the development of internal pores and fractures in sandstone, particularly at higher temperatures where interconnected fractures form a network within the rock. Cracks with widths close to 31 μm can be observed. The strengthening effect of thermal stress on sandstone gradually becomes inhibited by the damaging effect.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Xie, H. P., Ren, S. H., Xie, Y. C. & Jiao, X. M. Development opportunities of the coal industry towards the goal of carbon neutrality. J. China Coal Soc. 46, 2197–2211. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2021.0973 (2021).

Liu, W. D. Scientific Understanding of the belt and road initiative of China and related research themes. Progress Geogr. 34, 538–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2019.1571125 (2015).

Guo, P. Y., Bu, M. H., Zhang, P., Li, Q. B. & He, M. C. Review on catastrophe mechanism and disaster countermeasure of high geo-temperature tunnel. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 42, 1561–1581. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0186 (2023).

Zou, B. P., Luo, Z. Y., Xu, F. J., Ding, H. N. & Tao, Z. G. Experimental study on impact dynamic characteristics of deep sandstone under thermal-hydraulic-mechanical coupling conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39, 1750–1761. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2020.0205 (2020).

Wang, B., Sun, K., Liang, B., Chi, H. & Recovery, A. Experimental research on the mechanical character of deep mining rocks in THM coupling condition. Energy Sources, Part Utilization Environ. Eff. 00, 1660–1674 https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2019.1571125 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Mechanical behaviors of coal surrounding horizontal wellbore during drilling process considering the effects of loading rate, pore pressure and temperature. Geomechan. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-023-00561-z (2023).

Reppas, N., Davie, C. T. & Gui, Y. The Effects of Cooling on Fine-Grained Sandstone in Relation to Wellbore Injection of Carbon Dioxide. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03446-5(2023) (2023).

Liu, L. Y. et al. Mechanical properties of sandstone under in-situ high-temperature and confinement conditions. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater. 32 (4), 778–787 (2025).

Zha, W. H., Song, X. L. & Wu, T. F. Experimental study of mechanical characteristics of coal-serial sandy mudstone at different temperatures. Rock. Soil. Mech. 35, 1334–1339 (2014). http://ytlx.whrsm.ac.cn/CN/Y2014/V35/I5/1334

Lyu, C. et al. Experimental study on mechanical Properties, permeability and acoustic emission characteristics of gypsum rock under THM coupling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54 (11), 5761–5779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02586-w (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Effect of temperature on permeability of mudstone subjected to triaxial stresses and its application. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79761-w (2024).

Li, B. et al. Experimental study on damage and the permeability evolution process of methane-containing coal under different temperature conditions. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 184, 106509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106509 (2020).

Reppas, N. et al. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical (THM) wellbore analysis under sub-zero CO2 injection. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105954 (2024).

Yu, Y., Meng, Z., Gao, C., Lu, Y. & Li, J. Experimental investigation of pore pressure effect on coal sample permeability under different temperatures. Nat. Resour. Res. 31, 1585–1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-022-10033-y (2022).

Li, G. et al. Dynamic evolution of shale permeability under coupled temperature and effective stress conditions. Energy 266, 126320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.126320 (2023).

Brantut, N. & Baud, P. Development of permeability heterogeneity during compaction of porous sandstone. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JB030022(2025) (2025).

Chen, W. Z., Lei, J., Yu, H. D., Li, F. F. & Ma, Y. S. Study on coal adsorption-permeability model under the coupling of temperature and pore pressure. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 38, 1729–1746 (2019).

Jiang, H., Jiang, A., Zhang, F. & Feng, Y. Experimental investigation on the seepage characteristics and temperature–permeability (T–P) model of sandstone after different temperature treatments. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147, 13177–13189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-022-11526-x (2022).

Zhang, P. S., Zhao, C. Y., Hou, J. Q., Li, T. H. & Zhang, X. Experimental study on seepage characteristics of deep sandstone under temperature-stress-seepage coupling conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39, 1957–1974. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2020.0229 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Experimental investigation on permeability evolution of limestone caprock under coupled THM processes. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 38, 1819–1827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0886-4 (2019).

Lyu, C., Liu, J., Ren, Y., Liang, C. & Zeng, Y. Mechanical characteristics and permeability evolution of salt rock under thermal-hydro-mechanical (THM) coupling condition. Eng. Geol. 302, 106633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106633 (2022).

Bu, Y. S., Yang, S. Q. & Huang, Y. H. Experimental study on the influence of temperature and damage degree on permeability of sandstone. Eng. Mech. 38, 122–130. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2020.06.0374 (2021).

Wu, F. et al. Thermo-hydro-mechanical (THM) evolution law and development of permeability and pore structure of enhanced geothermal systems at ultra-high temperatures. Geothermics 97, 102253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geothermics.2021.102253 (2021).

Xie, Z. W., Ling, S. X., Liao, X. & Zhao, S. Y. Study on the weightless-expansion mechanism of red-layer mudstone at different heat treatment temperatures. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 42, 154–167. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0371 (2022).

Huang, Y. H., Yang, S. Q. & Teng, S. Y. Temperature dependence of the permeability of sandstone under loading and unloading conditions of confining pressure. Math. Geosci. 53, 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11004-020-09860-7 (2020).

Li, M., Wu, Z., Weng, L., Zhou, Y. & Liu, Q. Evaluating the pore characteristics of granite in disposal system under thermo-hydro-mechanical (T-H-M) coupling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 160, 105237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2022.105237 (2022).

Tian, W. L., Yang, S. Q., Elsworth, D., Wang, J. G. & Li, X. Z. Permeability evolution and crack characteristics in granite under treatment at high temperature. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 134, 104461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104461 (2020).

Zhu, A. et al. Experimental investigation on permeability, meso-damage and fractal characteristics of limestone caprock under THM coupling based on µ CT technology. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 212, 110197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110197 (2022).

Yan, B. Q., Ren, F. H., Cai, M. F., Guo, Q. F. & Chao, C. Research review of rock mechanics experiment and numerical simulation under THMC multi-field coupling. Chin. J. Eng. 43, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn2095-9389.2019.07.29.005 (2021).

Zuo, J. P., Xie, H. P., Zhou, H. W., Fang, Y. & Fan, X. Fractography of sandstone failure under temperature-tensile stress coupling effects. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6915.2007.12.009 (2007).

Meng, T. et al. Experimental study on permeability and porosity evolution of host rock with varying damage degrees in excavation damaged area under real-time ultra-high temperature and triaxial stress/seepage pressure condition. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 8075–8097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02408-x (2021).

Ministry of Electric Power Industry of the People’s Republic of China. GB/T50266-99 Standard for Tests Method of Engineering Rock Masses (China Planning, 1999).

Li, B. B., Gao, Z., Yang, K., Li, J. H. & Ren, C. H. Study on coal adsorption-permeability model under the coupling of temperature and pore pressure. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39, 668–681. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2019 (2020).

Zhang, Z. S. & Cui, G. X. Fluid Mechanic 3rd edn, 8 (Tsinghua University Press, 2015).

Zhang, P. S., Xu, D. Q., Yan, W., Li, H. X. & Fang, X. Study on the influence of post peak cyclic loading on sandstone mechanics and permeability characteristics under different confining pressures. Coal Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2023-0384( (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52568046, 41962017), the Natural Science Foundation in Guangxi Province of China (No. 2023GXNSFAA026185), the High-Level Innovation Team and Outstanding Scholars Program of Guangxi Institutions of Higher Learning of China (Gui Jiao Ren Cai [2020]6), the Doctoral Foundation of Guangxi University of Science and Technology (No. 03200009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and J.Y. were responsible for revising, reviewing and translating the first draft. W.H. was responsible for the conduct of the experiments and the processing of the data and the design of the graphs. J.W. is responsible for time planning and scheduling, and provides advice and methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Z., Huang, W., Yang, J. et al. Experimental study on mechanical and permeability behaviors of sandstone under real-time temperature. Sci Rep 15, 40151 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23869-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23869-0