Abstract

Pearl millet, recognized for its resilience to climate challenges, thrives in drought-prone and poor soil quality areas. This study aims to evaluate the impact of drought stress on six agronomic traits in 188 pearl millet accessions and identify stable and drought-tolerant accessions that can be developed into forage parental lines. Field experiments conducted in summer 2023 and 2024 under irrigated (control) and rainfed (stress) treatments at Hays, Kansas, revealed significant differences among the accessions, treatments, and year based on an aligned rank transform test for all the traits evaluated. The rank summation index selected 30 drought-tolerant germplasms per maturity group from the whole collection. Principal component analysis based on GBS SNP data indicated a higher level of genetic variation within the selected and unselected germplasms. By utilizing BLUP-based GGE biplot, MTSI, MGIDI, and FAI-BLUP stability models, we identified three early (E11—PI197115, E5—PI197368, and E12—PI197327), four medium (M19—PI197465, M5—PI197436, M1—PI197326, and M29—PI197069), and two late (L5—PI197291 and L19—PI197278) maturity accessions with broad adaptability across environments. Chlorophyll index, stay-green, and biomass traits served as effective indicators for drought tolerance, showing moderate to high heritability across maturity groups and stable performance across years. These results are crucial for developing drought-tolerant parental lines and hybrids with enhanced forage yield, addressing livestock feed challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A high crop yield variability due to inevitable environmental changes is becoming a common challenge for the long-term sustainability of global food and feed production1. Increased environmental variability affects grain yield, quantity and quality of biomass and forages for grazing, and profitability of farm operations2. The unpredictable and variable rainfall and precipitation and abiotic stresses like drought and high temperature (heat) are increasing the rate of conversion of irrigated crop acres to dryland, reducing the crop yields and lowering the land values3. The variation in rainfall distribution during the growing season in different areas around the globe impacts forage production2. In the United States (US), irrigation has reduced crop yield variability by 41%4. Expanding irrigation, however, puts more strain on the world’s freshwater supplies, frequently resulting in their unsustainable use5. The Kansas Water Plan strongly emphasized locally driven approaches to water management, suggesting focused efforts to increase crop water use efficiency (WUE) and the use of alternative crops to alleviate water scarcity6. Pre-breeding plays a crucial role in improving yield, and stress tolerance by identifying key traits or trait combinations, with germplasms providing essential genetic diversity7,8. These challenges to meet the global demand will be dependent on the continuous research efforts on screening germplasms to identify potential accessions for developing stress tolerant and high yielding hybrids involving both classical and molecular pre-breeding approaches. The pre-breeding multi-environment evaluation strategies for a stable yield with minimum drought impact will also be dependent on the available genetic resources and the subsequent selection for adaptation to challenging environmental stresses.

Existing forage crops in the US, like alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is known for its nutritional value and palatability but lacks to thrive in poorly drained soils and acidic conditions9. Clovers (Trifolium spp. L.) are good to improve soil fertility, but can have a high bloat potential in grazing animals if not managed carefully10. Corn silage (Zea mays L.) is also used as high-energy forage for livestock11, however it requires more water and proper moisture content for optimal fermentation12. These challenges associated with the forage crops need to be addressed. Alternative forage crops like sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum [L.] R. Br.) are being investigated by researchers and farmers for their drought tolerance and high silage yields requiring less water than corn13. Pearl millet, one of the alternative climate resilient crops, can be adapted as dryland grain, forage, and cover crop, suitable feed for poultry and livestock particularly for monogastric animals and humans14. Having evolved in Africa’s drought-prone arid and semi-arid areas, pearl millet outperforms other annual grass crops under non-irrigated and low rainfall conditions15, maintaining high yields with 381 to 584 mm of annual rainfall16. Hassanat17 reported that under dryland conditions, pearl millet produced 6322 and 97,511 kg ha−1 of forage dry matter harvested at the heading stage with 203 and 279 mm of rainfall, respectively.

In the 1990s, TifLeaf and Ghai forage cultivars of pearl millet were in cultivation for grazing, hay, cover crops, and forage purposes with 0.50 M ha−1 18 and a slight increase of 0.61 M ha−1 19 acreage in 2002 in the southeastern USA. Pearl millet is gaining importance again since 2019 as a promising forage crop substituting summer fallow in grain sorghum-winter wheat cropping systems in the southeastern USA region20,21. Unlike sorghum, pearl millet genetically possesses several unrealized forage attributes: short growing season with more tillers and high photosynthetic efficiency, thinner stems, and more feed value due to low lignin content and high palatability22. Above all, the absence of prussic acid23 makes pearl millet safe for summer grazing at any crop stage with high-quality forage24. The highest water-use efficiency (WUE) of forage pearl millet (6.13 Mg ha−1 mm−1) was reported by Crookston25 in tilled soil than in no-till and makes pearl millet a suitable alternative for drought-sensitive forage/feed crops. Sasani26 reported that irrigating pearl millet with 75% of its water requirement does not change its forage yield and quality while its WUE keeps increasing with higher water stress. However, the dry matter digestibility of forage pearl millet (64.0–69.0%) is slightly lower than forage corn (73.0%) but similar to forage sorghum (63.0%)17. Also, pearl millet forage yields (4.5–6.5 t ha−1) are lower than the 8–16 t ha−1 reported for forage sorghum in Western Kansas27.

Pearl millet is a cross-pollinated species, possessing a wide range of genetic variations, and the available diversified germplasm resources are not fully exploited for improving the agronomic traits, stress tolerance, and for high productivity in diverse agro-climatic conditions28,29,30. Globally, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), Research and Development Institute, and Global Genebank Information System (GRIN) have more than 66,000 diversified accessions that represent more than 140 pearl millet species. Unfortunately, limited research has been done for the development of genetic and genomic resources for forage traits in pearl millet31. Yadav and Bidinger32 reported that improved pearl millet varieties demonstrate high biomass production and superior forage quality compared to other cereal crops, making it a valuable alternative under water-limited conditions. Sustained breeding efforts are needed for increased forage yield potential with enhanced drought tolerance in pearl millet hybrid development, particularly for tropical and sub-tropical regions where water resource is limited.

Rank summation index (RSI) described by Mulamba and Mock33 is an ideal method to identify high-yielding and drought-tolerant germplasms, as it enables efficient multi-trait selection by ranking and summing germplasms across key traits. However, selecting superior genotypes for forage yield might be challenging since it is affected by multiple factors such as genotype (G), environment (E), and management (M) practices. This is further complicated by the genotype-by-environment interaction (GEI), thus slowing the genetic progress in breeding programs34. As a result, it is essential to understand how environmental variations influence genotypic traits and their adaptability in a specific stress condition. Different stability models such as ANOVA-based35,36, regression-based37 methods were used earlier, and additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) and genotype plus genotype-by-environment interaction (GGE) biplot38 were developed to apprehend the effects of the GEI for trait-based stability assessment. In recent times, multi-environment trial (MET) analysis has been developed, increasing the use of linear mixed-effect models such as best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) to analyze the MET data39. Multi-trait-based stability evaluation methods including multi-trait mean performance and stability index (MTSI), multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index (MGIDI), and multi-trait index based on factor analysis and genotype-ideotype distance (FAI-BLUP) index are the robust statistical tools for effective selection of stable accessions across different environmental conditions40,41,42. However, few studies addressing the selection of stable pearl millet cultivars using multi-trait-based stability evaluation methods have been reported43,44,45 and not for traits for forage improvement. The current research grounded in this context, and proposes a framework by using RSI, GGE biplot, MTSI, MGIDI, and FAI-BLUP indices for the selection of drought-tolerant and stable pearl millet germplasms that would be the basis for the parental lines and heterotic forage hybrid development with improved yield potential and drought tolerance across diverse environmental conditions.

We hypothesize that pearl millet germplasms representing different maturity groups in this study exhibit varying levels of drought tolerance, which can be quantified under field conditions to identify superior parental lines for forage hybrid development. The objectives of the study were to: (a) characterize the agronomic traits and molecular genetic diversity among pearl millet germplasms and classify them into distinct maturity groups (b) quantify the effects of limited water on key agronomic traits across the evaluated germplasms under contrasting moisture regimes (c) identify drought-tolerant germplasms within each maturity group as potential parental lines for forage pearl millet hybrid development.

Results

Weather parameters of the experimental site

The average temperature recorded during the cropping season of 2023 and 2024 was 22.0 and 22.9 °C, respectively, which is optimal46 (Fig. 1a). The amount of rainfall received in 2023 and 2024 was 254.5 and 271.5 mm respectively, indicating a considerable difference between the two years. Also, the rainfall received during the critical flowering period in August was highest in 2024 (106.9 mm) when compared to 2023 (95.3 mm) (Fig. 1b). Rainfed treatment received only natural rainfall and were not supplemented with irrigation, whereas, the irrigated treatment received timely supplementary irrigation to avoid drought stress. Irrigation (~ 25 mm) was provided during the critical growing stages (vegetative, flowering, and grain filling stage) in the irrigated (control) field experiments in both years. Historical weather data and rainfall pattern recorded during the cropping period confirmed that the rainfed treatment experienced significant soil moisture deficits, validating their use as a drought treatment in this study (Fig. 1). The moisture sensor (Teros12) used in summer 2024 recorded a cumulative moisture content of 1.28 cubic meters of water per cubic meter of soil (m3m−3) in the irrigated as compared to the rainfed treatment (0.694 m3m−3) from July to October (Fig. 1c). Mesonet data reflecting the soil moisture content in 2023 (0.72 m3 m−3) was nearly identical to Teros12 sensor measurements of 2024 rainfed treatment (0.69 m3 m−3) (Fig. 1c), indicating that drought stress in 2023 was comparable to that observed under rainfed conditions in 2024. Also, the strong positive correlation between Mesonet and rainfed measurements in 2024 (Fig. 1d) further supports the use of Mesonet records as a reliable proxy for assessing drought stress in 2023.

Weather parameters from Kansas Mesonet for the experimental station (ARCH, Kansas, USA). (a) Daily temperature and (b) monthly rainfall comparing the five year-average (2020–2024), 2023 and 2024, (c) monthly average soil moisture content comparing five-year average (Mesonet), 2023 (Mesonet), 2024 (Mesonet), experimental rainfed 2024 (Teros12 sensor), and experimental irrigated 2024 (Teros12 sensor), (d) Correlation between Mesonet 2024 soil moisture and experimental rainfed 2024 soil moisture showing a strong relationship.

Variation and mean performance

Aligned rank transform (ART) analysis revealed significant effect (p < 0.001) of genotype, treatment (irrigated and rainfed), and genotype × treatment interaction for all studied traits in both years (Table 1). Significant genotype × treatment interactions were observed for all traits indicating that genotype performance varied under irrigated and rainfed treatments. Pairwise treatment comparison using Kruskal–Wallis test (p < 0.001) showed that irrigated treatment significantly performed better than rainfed treatment for the traits including CL, PH, and BM in both years (Fig. 2). The mean performance of the germplasms under irrigated and rainfed treatments in both years across different maturity groups is given in Table 2. It was lower in rainfed treatment across the years within each maturity group for all traits except DF. Flowering was delayed for early and medium maturity groups in rainfed treatment in both years. However, there was no difference in the average DF mean performance for the late maturing germplasms under irrigated and rainfed treatments.

Inter-relationship analysis

An inter-relationship analysis was performed among the studied traits using the percent reduction for 2023 and 2024. The relationship within each trait between the years (2023 and 2024): CL (r = 0.35), SG (r = 0.17), and BM (r = 0.17) showed a significant positive correlation. In the relationship between the traits, CL showed a significant positive correlation with PH in both 2023 (r = 0.19) and 2024 (r = 0.25). Likewise, PH and PT showed a positive correlation across the years (r = 0.25 in 2023 and r = 0.15 in 2024). Whereas, a significant positive correlation was observed between CL and PT (r = 0.32) only in 2024 (Fig. 3).

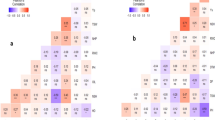

Rank summation index

The RSI was calculated separately for different maturity groups using the percent reduction values by considering all the evaluated traits for both 2023 and 2024 together (Fig. 4). Based on the RSI results, 90 germplasms were selected (30 from each maturity group) (Supplementary Table S1) for stability analysis.

Heatmap of rank summation index based on the percent reduction of 2023 and 2024 for (a) early (b) medium, and (c) late maturing pearl millet germplasms for all the traits together. Blue cells: germplasms with a lower percent reduction, thus being drought-tolerant; Red cells: indicate germplasms with a higher percent reduction, thus being drought-susceptible. CL, chlorophyll index; PH, plant height; PT, number of productive tillers; SG, stay-green; BM, biomass.

Genetic structure

Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using SNP markers generated through genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), which enables cost-effective, high-throughput genome-wide genotyping. The use of GBS-derived SNPs allowed for a dense and unbiased representation of the genetic variation across the 188 germplasm accessions. The first two principal components accounted for a cumulative variance of 16.8%, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 9.1% and 7.8%, respectively (Fig. 5). Despite the modest proportion of variance explained, the PCA revealed broad genetic dispersion, indicating significant diversity within the panel. The subset of 90 selected accessions—comprising 30 each from early, medium, and late maturity groups—were distributed across the PCA plot, demonstrating that the selection effectively captured genetic diversity both between and within maturity classes.

Multi-traits-based stability analysis

BLUP-based GGE biplot

The BLUP-based GGE biplot selected stable and high-ranking germplasms from different maturity groups for traits CL, PH, PT, SG, and BM based on their close relatedness to the ideal germplasm (Fig. 6). The first two PCs accounted for 63.46% of the total variation for the early, 64.08% for medium, and 58.19% for the late maturity group. For the early maturing, germplasms E12, E11, E3, E5, E26, and E2 were positioned closer to the center of the concentric circle, indicating greater stability (Fig. 6a). Similarly, germplasms M29, M1, M21, M19, M5, and M28 in the medium-maturity group (Fig. 6b), and L4, L19, L1, L13, L5, L16, and L2 in the late maturity group (Fig. 6c) were closer to the center, reflecting their stability.

Multi-trait mean performance and stability index (MTSI)

MTSI index ranks the germplasms by employing information from the agronomic traits CL, PH, PT, SG, and BM in and across the environments. Utilizing a selection intensity of 20%, six superior germplasms with high mean performance and stability were selected among the early, medium, and late maturity groups (Fig. 7). From the early maturing group, germplasms E11, E5, E8, E12, E22, and E10, showing low MTSI index, thus indicating the stable performance of the selected germplasms (Fig. 7a). Similarly, M19, M5, M1, M28, M15, and M29 in the medium (Fig. 7b), and L17, L16, L5, L19, L12, and L2 in the late maturity group were selected as superior germplasms (Fig. 7c).

Multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index (MGIDI)

Utilizing a selection intensity of 20%, six germplasms were selected by the MGIDI index within each maturity group. The selected germplasms exhibited a low MGIDI index, indicating more closeness to the ideal ideotype. For the early maturing, germplasms E12, E11, E5, E25, E3, and E28 were selected based on their low MGIDI scores (Fig. 8a). Germplasms M19, M21, M29, M24, M1, and M5 were selected from the medium-maturing (Fig. 8b). For late maturing, L12, L4, L5, L17, L19, and L1 were selected as the ideal germplasms (Fig. 8c).

Multi-trait index based on factor analysis and genotype-ideotype distance (FAI-BLUP)

Based on a selection intensity of 20%, FAI-BLUP selected six superior germplasms within each maturity group with a low FAI-BLUP score. For early maturing, E12, E11, E5, E3, 26, and E28 were selected as ideal germplasms (Fig. 9a). Germplasms M19, M21, M29, M1, M5, and M28 were ideal for medium-maturing (Fig. 9b). For late maturing, L12, L5, L4, L17, L16, and L19 were selected as the ideal germplasms (Fig. 9c).

Selection differential, heritability, and selection gain

The selection differential percentage (SD%), heritability (h2), and selection gain percentage (SG%) were calculated using the estimates obtained from the three stability indices (MTSI, MGIDI, and FAI-BLUP). In this study, h2 ranged from low (0.2–0.4), moderate (0.4–0.7), and high (> 0.7) across traits and maturity groups, and similarly, variation in SD% contributed to differences in SG% (Table 3). Based on SG% values from the different models across all maturity groups, FAI-BLUP provided the highest SG% for CL, PH, and PT in early-maturing germplasms. MTSI showed higher SG% for multiple traits including CL, PH, and SG in medium and late maturity groups, as well as SG in early maturity and BM in early maturity. MGIDI provided the highest SG% for PT in late and for BM in medium maturing germplasms. Overall, MTSI was the most robust and consistently effective model for maximizing genetic gain across traits and maturity groups in this study (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the drought tolerance of 188 pearl millet germplasms for forage yield potential. There was no considerable difference in the average temperatures recorded but with notable variations in the amount and distribution of rainfall received during the cropping period in 2023 and 2024, resulting in significant variations in the performance of the germplasms across the years. The increase in precipitation in summer 2024 as compared to 2023 enhanced the soil moisture levels, which is crucial for facilitating essential physiological processes like photosynthesis and transpiration during the crop’s growth cycle47. Soil moisture comparisons further revealed that Mesonet 2023 data aligned with rainfed 2024 conditions (Fig. 1c), highlighting consistency in drought stress patterns across years, while the strong correlation between Mesonet and Teros12 measurements in 2024 validated the use of Mesonet observations as reliable proxies for rainfed field-level soil moisture48. Also, the lower CL, PH, and PT in 2023 compared to 2024 can be attributed to the relatively low rainfall during the critical flowering period and overall cropping season in 2023. Drought stress, especially during the flowering stage reduces pollen viability and seed production, resulting in lowered yields and performance49.

Despite these differences, both years-imposed moisture stress in rainfed, with aligned rank transform (ART) and Kruskal–Wallis tests confirming highly significant treatment effects and genotype × environment interactions (Fig. 2). The instability of genotype performance across irrigated and rainfed conditions underscores the need for multi-environment testing under variable rainfall regimes. These findings emphasize the need to understand rainfall variability and its influence on pearl millet performance. Breeding efforts aimed at improving drought tolerance and adaptability to varying rainfall distribution could strengthen the crop’s resilience to environmental fluctuations50,51,52. Also, the use of ART for non-parametric factorial analysis in this study was effective in dissecting genotype × treatment effect in irregular distributed data without distorting the original scale which are common drawbacks of transformation-based approaches53.

A significant positive correlation within chlorophyll index, stay-green, and biomass was observed over the years. Ali54 reported similar results with a significant positive relationship between chlorophyll and stay-green in wheat. These three traits also exhibited moderate to high heritability across each maturity group, indicating a strong genetic control and stability across years, thus making them as reliable indicators of drought resilience55,56,57,58. PH and PT also showed a positive association with each other across the years. Interestingly, the positive correlation of CL with PH and PT, indicates that chlorophyll retention might contribute to improved plant height and panicle traits under stress conditions59,60. Fodder quality and biomass are influenced by various factors61, with most of them showing a positive correlation with each other31. Saygidar62 reported a positive correlation between biomass yield, plant height, number of tillers per plant, dry matter digestibility rate, relative feed value, and crude protein in pearl millet. The use of percent reduction values for correlation analysis provides a reliable depiction of the relative impact of drought on the studied traits, as it accounts for the degree of stress-induced variability. It provides valuable insights into the interrelationships among the component traits, which can aid in selecting drought-tolerant germplasms. Xu63 reported the use of drought tolerance index (DI) for analyzing the correlation of eight yield-related traits in spring wheat and observed a positive relationship between DIs of chlorophyll index and PH.

For selecting drought-tolerant germplasm, we used RSI based on the percent reduction64 by considering all the studied traits (CL, PH, PT, SG, and BM) for both 2023 and 2024 together. We narrowed down the preliminary selection by using RSI from 188 to 90 germplasms and classified into three maturity groups (early, medium, and late), each with the top thirty ranked germplasms, exhibiting low percent reduction and high drought tolerance. The genetic structure analysis also confirmed wide variation among the selected accessions within each maturity group. This classification is based on flowering time, a crucial trait for adaptation to climatic variability as it ensures the crop’s development coincides with the rainy period65. Ramalingam45 used RSI using percent reduction to select drought-tolerant seed and pollinator parental lines in pearl millet. Similarly, Okoli66 reported the selection of green maize hybrids based on RSI.

The widespread distribution of the 90 selected accessions in the PCA space confirms that the germplasm selection strategy between and within each maturity group captured the wide genetic diversity of the full panel. Additionally, the germplasm dispersion within each group reflects intra-group variability, supporting the utility of this panel for downstream applications such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS), genomic prediction, or other targeted breeding efforts30.

The significance of genotype × treatment effect for the traits under study revealed they are controlled by polygenes and is challenging to make an effective selection of stable germplasms across diverse environments. It is clearly demonstrated through the difference in the mean performance of the studied germplasms with a significant genotype, treatment, and year interaction for all the traits under study. RSI was used to identify drought-tolerant accessions considering the difference in control and stress environments performance. However, identifying stable accessions adaptable to multi-environments by tackling the limitations of GEI necessitates robust methods to address these challenges67. Lee68 highlighted the use of multi-environmental trials and stability analysis for evaluating yield-related traits across different maturity groups for the selection of stable genotypes in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mohammadi69 investigated the effectiveness of different yield-based drought-tolerant indices in durum wheat and reported that the stress susceptible index (SSI)70, tolerance index (TOI)71, and yield stability index (YSI)72 models were inaccurate in identifying drought-tolerant stable genotypes particularly in dryland areas. Stress susceptibility index (SSI) used by Yadav and Bidinger32 in pearl millet had a limitation as it considered change in genotype performance from control to stress treatment. For drought screening, Yadav73 suggested not to use the drought response index (DRI) to identify drought-tolerant pearl millet population due to many limitations.

By considering these limitations reported in the earlier studies, we used four advanced stability models: BLUP-based-GGE biplot74, MTSI41, MGIDI42, and FAI-BLUP40 in this investigation. These four models in recent studies were used and justified the significance and reliability of the selection of stable genotypes. BLUP-based-GGE biplot has the greatest relative ability to distinguish among accessions selected for consistent performance across diverse environments74. Zuffo75 recommended MTSI as this model is more efficient for the selection of stable genotypes across adverse drought and saline stress environments. A simulation study by Olivoto76 clearly indicated that MGIDI is a multi-trait-based framework highlighting the uniqueness and robustness of the model to analyze multivariate data across diverse environments. Progeny selection using FAI-BLUP index was effective in soybean (Glycine max L.) for stability performance as this model was balanced with desirable genetic gains for all traits simultaneously77.

The results from these four robust models facilitated more efficient and reliable selection of accessions from each maturity group with stable performance across four environments. These four advanced stability models clearly justified the efficiency of each model to delineate the G × E interactions and is clearly revealed in the selection of most of the stable genotypes identified by each model were different except few in all three maturity groups (Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9 and Table 4). Several studies in other cereals have reported the use of combination of these indices for consistently selecting stable genotypes in sorghum78, maize79,80, wheat69, and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.)81,82.

Most of the accessions identified through FAI-BLUP and GGE biplot analyses were common across maturity groups, reflecting a consistent trend between the two models. Most accessions selected across the four models overlapped in at least two of them, while MTSI uniquely identified three accessions from the early maturity group that were not captured by the other three models. Venn diagrams, as a visualization tool was used to bring all the selected accessions together by different stability indices and identified the commonly shared accessions by all four models for each maturity group. Three accessions (E11—PI197115, E5—PI197368 and E12—PI197327) from early, four (M19—PI197465, M5—PI197436, M1—PI197326, and M29—PI197069) from medium and two (L5—PI197291 and L19—PI197278) from late maturity exhibited wide adaptation, demonstrating stable performance across four environments as these selected drought-tolerant accessions were commonly identified in all four stability models (Fig. 10). Naveen43 conducted similar study by using four different stability models, assessed the selection efficiency and identified ideal and stable genotypes from a diverse global set of 248 pearl millet genotypes evaluated in diverse environments. The selected nine drought-tolerant pearl millet germplasms from this study will be further used for quality traits’ analyses for the development of hybrids with improved forage yield potential and quality traits.

Venn diagram with the accessions selected by MTSI, MGIDI, FAI-BLUP indices, and GGE-Biplot for (a) early (b) medium, and (c) late maturing germplasms. MTSI: Multi-trait stability index; MGIDI: Multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index; FAI_BLUP: factor analysis genotype-ideotype distance- best linear unbiased predictions; GGE_Biplot: genotype plus genotype-by-environment biplot. Common accessions selected by different indices: Early maturity: PI197115 (E11), PI197368 (E5), PI197327 (E12), Medium maturity: PI197465 (M19), PI197436 (M5), PI197326 (M1), PI197069 (M29), Late maturity PI197291 (L5), PI197278 (L19).

Conclusions and future research

This study primarily focused on traits such as chlorophyll index, staygreen, plant height, productive tillers, and biomass which are related to drought tolerance. The stability performance cross-validated through four stability models (BLUP-based GGE biplot, MTSI, MGIDI and FAI-BLUP) selected nine drought-tolerant germplasms (Early: PI197115, PI197368, PI197327; Medium: PI197465, PI197436, PI197326, PI197069; Late: PI197291, PI197278) from different maturity groups. These drought-tolerant selected nine accessions recorded higher mean performance for chlorophyll index, productive tillers and biomass across 188 germplasms indicating as potential source for parental lines and hybrid development with increased forage yield potential under drought stress environments. The findings of this study also suggest that traits such as chlorophyll index and stay-green could serve as reliable indicators of drought tolerance in pearl millet for improved forage yield potential. Additionally, biomass-related traits like plant height and productive tillers, despite exhibiting variability, hold the potential for enhancing biomass production per unit area. These insights contribute to forage breeding strategies aimed at improving drought resilience and biomass yield in pearl millet under water-limited conditions. The decision to limit the scope to these traits was due to the extensive screening of 188 germplasms, making the inclusion of forage-quality traits in these large collections practically cumbersome and challenging. Future research is required to address this gap by characterizing the selected nine germplasms from all three maturity groups in this study for key forage quality traits, including wet biomass at different stages followed by quality traits like crude protein content, in vitro digestibility, neutral detergent fiber content, acid detergent fiber content, lignin content, and cellulose and hemicellulose content. These evaluations will enhance the understanding of forage potential and nutritional value, contributing to the development of high yielding pearl millet parental lines and forage hybrids with improved yield potential.

Materials and methods

Planting materials

Out of 309 pearl millet germplasms received from International Crop Research in Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), Niger, West Africa30, 188 photo-insensitive accessions were used for this study (Supplementary Table 1). These accessions with diverse geographic origins were selected based on their photoperiod insensitivity. These accessions are being maintained through repeated selfed generations at the Kansas State University Agriculture Research Center, Hays (ARCH), Kansas, USA.

Field experiments

The accessions were evaluated under irrigated (control) and rainfed (stress) treatments at ARCH, KS (latitude 38.9798 N, longitude 99.3268 W; soil type: Harney silt loam), in the summer 2023 and 2024. Two-row plots with a length of 3 m and a 1.5-m alley were arranged in an augmented block design across the four environments. The irrigated treatment received natural rainfall and three supplemental irrigations throughout the cropping season. In contrast, the rainfed treatment depended entirely on natural rainfall, thus representing the drought stress. Three supplemental irrigations were provided to irrigated treatment at three critical growth stages: vegetative, flowering, and grain filling. Weather parameters like temperature, rainfall, and soil moisture from the experimental station were recorded for five-year average, 2023, and 2024 using the Kansas Mesonet (https://mesonet.k-state.edu/weather/historical/). Teros 12 soil moisture sensor was used to record the daily soil moisture content in summer 2024 irrigated and rainfed field experiments. In 2023, soil moisture data from the Kansas Mesonet were used because in-field soil moisture sensors were not installed that season. The Mesonet station is located within the experimental site and provides high-resolution, standardized soil moisture measurements. Its 2024 data closely matched the in-field Teros 12 sensor data collected in 2024, justifying its use as a reliable proxy for quantifying drought stress in 2023.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Three plants were randomly selected from each plot for data collection. The agronomic traits such as days to 50% flowering (DF), chlorophyll index (CL), plant height (PH), stay-green (SG), number of productive tillers (PT), and biomass (BM) were measured at different developmental stages of the plants. The days to 50% flowering were recorded as the days from planting until 50% of the accessions had female flowers. Chlorophyll meter SPAD-502 Plus (Model 502, Spectrum Technologies, Plainfield, IL) was used to measure the chlorophyll index 10 days after the anthesis. The average of five measurements taken from different areas of the flag leaf was calculated and recorded as a single reading per plant. Plant height expressed in centimeters was measured from the soil surface to the tip of the main stem. Plot-based visual scoring of the stay-green rating was done at or shortly after physiological maturity. A scale of 1 to 10 was used to assign scores based on the percentage of green leaves56. A rating of 1 indicated 10% green leaves, 5 indicated 50% green leaves and 10 indicated 100% green leaves. The number of productive tillers was counted per plant and the biomass was recorded by weighing the harvested above-ground plant material in grams (g) per plant.

Non-parametric test

Data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro–Wilk83 and Levene’s84 tests, respectively, and found to be non-normally distributed. Therefore, an aligned rank transform (ART) non-parametric analysis was conducted using the ARTool package85 in R version 4.4.2 to assess the effects of genotype, treatment, and genotype × treatment interactions separately for each year. Pairwise comparisons between treatments were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test86. Results were graphically visualized using the ggplot2 package in R version 4.4.287.

Percent reduction and rank summation index

All 188 accessions were classified into three maturity groups based on the average data of days to 50% flowering from irrigated field experiments in summer 2023 and 2024 as: early maturing (55–65 days), medium-maturing (66–75 days), and late maturing (> 75 days)88,89. Equation (1) was used to calculate percent reduction for each trait using the average values of the three plants per plot.

where IR and RF indicate the average value of the trait under irrigated and rainfed treatments, respectively. Based on the percent reduction, a multi-criteria selection procedure known as rank summation index (RSI) was employed to identify the highest-ranked germplasms by simultaneously evaluating all five traits (CL, PH, SG, PT, and BM) together45. Germplasms with the least percent reduction were ranked first while those with the highest were ranked last. The thirty highest-ranked accessions were selected within each maturity group and advanced for further analysis. The corrplot package in R version 4.4.2 was used to perform the correlation90 using the percent reduction values for the traits under study for 2023 and 2024.

Genetic structure

We used single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers developed through genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) method to verify the genetic variation in the selected germplasms in this present investigation. Fresh leaf tissues (50 mg) were collected from 188 pearl millet germplasms at the 5-leaf stage. DNA was extracted and genotyped at the University of Minnesota Genomic Center (UMGC). DNA samples were digested using the restriction enzymes Pstl (CTGCAG) and Mspl (CCGG) and barcode adapters were ligated to individual samples. The sequence data was trimmed and the quality control of reads was verified before and after trimming using FASTQC. SNPs were called using the Tift 23D2B1-P1-P5 reference genome91. SNPs with missing rate > 20%, minor allele frequency < 0.05, and heterozygosity > 0.1 were removed92. The retrieved SNPs were first imputed using beagle imputation and later pruned using Plink, yielding 13,576 high-quality SNPs. Principle component analysis (PCA) was performed where two PCA axes were built with the 188 pearl millet accessions and the selected germplasms from each maturity group were projected on these axes using the ggplot2 package in R version 4.4.2.

Multi-traits-based stability analysis

In this study, four different multi-trait-based models such as BLUP-based GGE biplot, MTSI, MGIDI, and FAI-BLUP were used to identify the reliable and consistent stable accessions across diverse environments by considering all the measured traits together. The gge () function from the metan package in R version 4.4.2 was used to perform the GGE biplot analysis using the BLUP values93. For other three models (MTSI, MGIDI, and FAI-BLUP) the metan package in R version 4.4.2 was used to calculate the different indices using different functions94.

BLUP-based GGE biplot

Best linear unbiased predictions (BLUP) were predicted by considering year and treatment as fixed effects while the genotype and replication nested within the year and treatment as random effects. Equation (2) was used to calculate the linear mixed-effects model using the lme4 package in R version 4.4.2

where Yijklm is the observed value of the trait, μ is the overall mean, Yeari and Treatmentj are fixed effects for the ith year and jth treatment, respectively, Gk is the random effect of the kth genotype, and Rl(ij) is the random effect of the lth replication nested within the ith year and jth treatment combination. The residual error is represented by εijklm95.

Multi-trait mean performance and stability index (MTSI)

Equation (3) was used to estimate the multi-trait mean performance and stability index.

where MTSIi is the multi-trait stability index of the ith genotype, Fij is the jth score of the ith genotype, and Fj is the jth score of the ideotype. The MTSI was calculated using the mtsi () function from the metan package41.

Multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index (MGIDI)

The MGIDI was determined as described by Olivoto and Nardino42 in four steps: (a) rescaling the traits (b) using factor analysis (c) planning ideotype and (d) computing the MGIDI index. Equation (4) was used to calculate MGIDI.

where MGIDIi is the multi-trait genotype-ideotype for the ith genotype, Yij is the score of the ith genotype in the jth factor (i = 1, 2… g; j = 1, 2… f; g and f being number of genotypes and factors respectively), and Yj is the jth score of ideotype. The “gamem” and “mgidi” functions in the metan package were used to calculate the MGIDI index96.

Multi-trait index based on factor analysis and genotype-ideotype distance (FAI-BLUP)

After defining the ideotype, the distance of each genotype from the ideotype was determined and transformed into a spatial probability, which in turn allowed the genotype ranking. Equation (5) was used to estimate the FAI-BLUP index.

where Pij is the probability that the ith (i = 1,2,…,n) genotype is the same as the jth (j = 1,2,…,m) genotype; dij is the genotype-ideotype distance from the ith genotype to the jth ideotype, based on the normalized Euclidean distance mean44. The FAI-BLUP index was estimated using the fai_blup () function in the metan package94.

The Venn diagram was created using the venn_plot () function in the metan package in R version 4.4.294.

Selection differential, heritability, and selection gain

Equation (6) was used to calculate the selection differential (ΔS) using the percentage of population mean97.

Equation (7) was used to calculate the broad sense heritability (h2) based on mean performance.

where σ2g, σ2i, and σ2e are variances related to genotypes; genotype-environment interaction, and error respectively; e and b refer to the number of environments and blocks per environment, respectively.

Equation (8) was used to compute selection gain (ΔSG) percentage under selection.

where Xo is the mean for WAASBY index of the original population; Xs is the mean for WAASBY index of selected genotypes; h is heritability.

We calculated selection differential percentage (SD%), heritability percentage (h2), and selection gain percentage (SG%) from only three stability models (MTSI, MGIDI and FAI-BLUP). For all stability models, h2 value < 0.4 as low, 0.4 to 0.7 as moderate and > 0.7 as high heritability were considered45. Unlike heritability, SD% and SG%—do not have fixed universal classification ranges, as their values are trait- and scale-dependent. SG% reflects the expected outcome of selection, as it integrates SD% and h2. In this study, SG% was interpreted to show the best stability model across traits and maturity groups.

Data availability

The genomic data of the 311 pearl millet germplasms collected in this study have been deposited into the NCBI database under accession code PRJNA1224272. Other additional relevant data are included in the manuscript and supplementary table files.

Abbreviations

- RSI:

-

Rank summation index

- BLUP-based GGE biplot:

-

Best linear unbiased predictions based genotype plus genotype-by-environment interaction biplot

- MTSI:

-

Multi-trait mean performance and stability index

- MGIDI:

-

Multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index

- FAI-BLUP:

-

Multi-trait index based on factor analysis and genotype-ideotype distance

References

McKenzie, F. C. & Williams, J. Sustainable food production: Constraints, challenges and choices by 2050. Food Sec. 7, 221–233 (2015).

Giridhar, K. & Samireddypalle, A. Impact of climate change on forage availability for livestock in Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation. (ed. Sejian, V.) 97–112 (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2265-1_7

Suttles, K. M. et al. Kansas agriculture in 2050: a pathway for climate-resilient crop production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 1404315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1404315 (2024).

Kukal, M. S. & Irmak, S. Impact of irrigation on interannual variability in United States agricultural productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 234, 106141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106141 (2020).

Dalin, C., Wada, Y., Kastner, T. & Puma, M. J. Groundwater depletion embedded in international food trade. Nature 543, 700–704. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21403 (2017).

Kansas Water Office. 2022 Kansas Water Plan. Topeka, KS: Kansas Water Office. Accessed 12.20.24; https://www.kwo.ks.gov/water-plan/water-plan (2022).

Sukumaran, S., Rebetzke, G., Mackay, I., Bentley, A.R., & Reynolds, M.P. Pre-breeding strategies in Wheat Improvement (ed. Reynolds, M.P., & Braun, HJ.). 451–469 (Springer, Cham. 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90673-3_25

Prasanth, A., Premnath, A. & Muthurajan, R. Genetic divergence study for duration and biomass traits in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Electron. J. Plant Breed. 12, 22–27 (2021).

Undersander, D. et al. (eds) Alfalfa Management Guide (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Bloat, F. P. Forage Facts. https://www.asi.k-state.edu/doc/forage/fora17.pdf

Karnatam, K. S. et al. Silage maize as a potent candidate for sustainable animal husbandry development—perspectives and strategies for genetic enhancement. Front. Genet. 14, 1150132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1150132 (2023).

Muck, R. E. Silage microbiology and its control through additives. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 39, 183–191 (2010).

Sattler, S. E., Funnell-Harris, D. L. & Pedersen, J. F. Brown midrib mutations and their importance to the utilization of maize, sorghum, and pearl millet lignocellulosic tissues. Plant Sci. 178, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.01.001 (2010).

Davis, A. J., Dale, N. M. & Ferreira, F. J. Pearl millet as an alternative feed ingredient in broiler diets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 12, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/japr/12.2.137 (2003).

Hassan, M. U. et al. Growth, yield and quality performance of pearl millet (Pennisetum americanum L.). Am. J. Plant Sci. 5, 2215–2223. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2014.515235 (2014).

Lee, R. D. et al. Pearl millet for grain. Univ. Georgia Bull. 1216, 1–8 (2009).

Hassanat, F. M. Evaluation of pearl millet forage (McGill University, 2007).

Andrews, D. J. & Kumar, K. A. Pearl millet for food, feed, and forage. Adv. Agron. 89, 89–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60936-0 (1992).

Myers, R. L. Alternative crop guide: pearl millet. Accessed: Sep 15, 2024. Jefferson Institute. http://www.Jeffersonian.org (2002).

Baumhardt, L. R. & Salinas-Garcia, J. Dryland agriculture in Mexico and the U.S. Southern Great Plains. Dryland Agric. 23, 341–364. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr23.2ed.c10 (2006).

Bhattarai, B., Singh, S., West, C. P. & Saini, R. Forage potential of pearl millet and forage sorghum alternatives to corn under the water-limiting conditions of the Texas High Plains: A review. Crop Forage Turfgrass Manag. 5, 190058. https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2019.08.0058 (2019).

Nagaraja, T. E. et al. Millets and pseudocereals: A treasure for climate resilient agriculture ensuring food and nutrition security. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 84, 1–37 (2024).

Sedivec, K. K. & Schatz, B. G. Pearl millet: Forage production in North Dakota (1991).

Burton, G. W. & Forston, J. C. Inheritance and utilization of five dwarfs in pearl millet (Pennisetum typhoides) breeding. Crop Sci. 6, 69–70. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1966.0011183X000100010022x (1966).

Crookston, B., Blaser, B., Darapuneni, M. & Rhoades, M. Pearl millet forage water use efficiency. Agronomy 10, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10111672 (2020).

Sasani, S., Jahansooz, M. R. & Ahmadi, A. The effects of deficit irrigation on water-use efficiency, yield, and quality of forage pearl millet. Agron. Plant Breed. 150, 1–5 (2004).

Holman, J., Obour, A., Dooley, S. & Roberts, T. Kansas summer annual forage hay and silage variety trial. Kansas Agric. Exp. Stn. Res. Rep. 8, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.4148/2378-5977.8328 (2022).

Passot, S. et al. Characterization of pearl millet root architecture and anatomy reveals three types of lateral roots. Front. Plant Sci. 7(829), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00829 (2016).

Shivhare, R. & Lata, C. Exploration of genetic and genomic resources for abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in pearl millet. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.02069 (2017).

Kanfany, G. et al. Genomic diversity in pearl millet inbred lines derived from landraces and improved varieties. BMC Genomics 21, 469. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06796-4 (2020).

Daduwal, H. S., Bhardwaj, R. & Srivastava, R. K. Pearl millet a promising fodder crop for changing climate: A review. Theor Appl Genet 137, 169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-024-04671-4 (2024).

Yadav, O. P. & Bidinger, F. R. Dual-purpose landraces of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) as sources of high stover and grain yield for arid zone environments. Plant Genet. Resour. 6, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262108993084 (2008).

Mulamba, N. N. & Mock, J. J. Improvement of yield potential of the Eto Blanco maize (Zea mays L.) population by breeding for plant traits. Egypt. J. Genet. Cytol. 7, 40–51 (1978).

Quintero, A., Molero, G., Reynolds, M. P. & Calderini, D. F. Trade-off between grain weight and grain number in wheat depends on GxE interaction: A case study of an elite CIMMYT panel (CIMCOG). Eur. J. Agron. 92, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2017.09.007 (2018).

Yates, F. & Cochran, W. G. The analysis of groups of experiments. J. Agric. Sci. 28, 556–580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600050978 (1938).

Shukla, G. K. Some statistical aspects of partitioning genotype-environmental components of variability. Heredity 29, 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.1972.87 (1972).

Eberhart, S. T. & Russell, W. A. Stability parameters for comparing varieties. Crop Sci. 6, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1966.0011183X000600010011x (1966).

Yan, W., Kang, M. S., Ma, B., Woods, S. & Cornelius, P. L. GGE biplot vs. AMMI analysis of genotype-by-environment data. Crop Sci. 47, 643–653. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2006.06.0374 (2007).

van Eeuwijk, F. A., Bustos-Korts, D. V. & Malosetti, M. What should students in plant breeding know about the statistical aspects of genotype × environment interactions?. Crop Sci. 56, 2119–2140. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2015.06.0375 (2016).

Rocha, J. R. A. S. C., Machado, J. C. & Carneiro, P. C. S. Multitrait index based on factor analysis and ideotype-design: Proposal and application on elephant grass breeding for bioenergy. GCB Bioenergy 10, 52–60 (2018).

Olivoto, T., Lúcio, A. D. C., da Silva, J. A. G., Sari, B. G. & Diel, M. I. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials II: Selection based on multiple traits. Agron. J. 111, 2961–2969. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.03.0221 (2019).

Olivoto, T. & Nardino, M. MGIDI: Toward an effective multivariate selection in biological experiments. Bioinformatics 37, 1383–1389. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa981 (2021).

Naveen, A. et al. Delineation of selection efficiency and coincidence of multi-trait-based models in a global germplasm collection of pearl millet for a comprehensive assessment of stability and high-performing genotypes. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-024-02245-3 (2024).

Khandelwal, V. et al. Identification of stable cultivars of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) based on GGE Biplot and MTSI index. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 84, 668–678. https://doi.org/10.3174/ISGPB.84.4.18 (2024).

Ramalingam, A. P. et al. Drought tolerance and grain yield performance of genetically diverse pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) seed and restorer parental lines. Crop Sci. 64, 2552–2568. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.21271 (2024).

Djanaguiraman, M., Sofi, P. A., Shanker, A. K., Ciampitti, I. A., Perumal, R. & Prasad, P. V. V. Growth and development of pearl millet. In Pearl Millet: A Resilient Cereal Crop for Food, Nutrition, and Climate Security 225–247 (2024).

Blum, A. Plant BREEDING for Water-Limited Environments (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Waite, J. Corn and forage sorghum yield and water use in Western Kansas (Master’s thesis, Kansas State University). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (2016). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/corn-forage-sorghum-yield-water-use-western/docview/1872340994/se-2

Bidinger, F. R., Mahalakshmi, V. & Rao, G. D. P. Assessment of drought resistance in pearl millet [Pennisetum americanum (L.) Leeke] I. Factors affecting yields under stress. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 38, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9870037 (1987).

Li, Z. et al. Melatonin improves drought resistance in maize seedlings by enhancing the antioxidant system and regulating abscisic acid metabolism to maintain stomatal opening under PEG-induced drought. J. Plant Biol. 64, 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-021-09297-3 (2021).

Serraj, R., Buhariwalla, H. K., Sharma, K. K., Gaur, P. M. & Crouch, J. H. Crop improvement of drought resistance in pulses: A holistic approach. Indian J. Pulses Res. 17, 1–13 (2004).

Hash, C. T. et al. Marker-assisted backcrossing to improve terminal drought tolerance in pearl millet in Molecular approaches for the genetic improvement of cereals for stable production in water-limited environments (ed. Ribaut J.M & Poland D.) 114–119 (CIMMYT, 2000).

Mansouri, H., Paige, R. L. & Surles, J. G. Aligned rank transform techniques for analysis of variance and multiple comparisons. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 33, 2217–2232 (2004).

Ali, A., Ullah, Z., Sher, H., Abbas, Z. & Rasheed, A. Water stress effects on stay-green and chlorophyll fluorescence with focus on yield characteristics of diverse bread wheats. Planta 257, 104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-023-04140-0 (2023).

Ochieng, G. A. Novel sources of the stay-green trait in sorghum and its introgression into farmer preferred varieties for improved drought tolerance. (University of Nairobi, Kenya, 2022). http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/161501

Xu, W., Rosenow, D. T. & Nguyen, H. T. Stay green trait in grain sorghum: relationship between visual rating and leaf chlorophyll concentration. Plant Breed. 119, 365–367. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0523.2000.00506.x (2000).

Kumar, R. et al. Stay-green trait serves as yield stability attribute under combined heat and drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Growth Regul. 96, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-021-00758-w (2022).

Ramkumar, M. K. et al. A novel stay-green mutant of rice with delayed leaf senescence and better harvest index confers drought tolerance. Plants 8, 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100375 (2019).

Wasaya, A. et al. Evaluation of fourteen bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes by observing gas exchange parameters, relative water and chlorophyll content, and yield attributes under drought stress. Sustainability 13, 4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094799 (2021).

Singh, A. K., Singh, S. K., Garg, H. S., Kumar, R. & Choudhary, R. Assessment of relationships and variability of morphophysiological characters in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress and irrigated conditions. Bioscan 9, 473–484 (2014).

Minson, D. J. Forage in ruminant nutrition (Academic Press, 1990).

Sayğıdar, N., Yücel, C. & Taş, T. Determination of biomass yield, forage quality and mineral content of pearl millet varieties (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) under semi-arid conditions. Black Sea J. Agric. 7(5), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.4711/bsagriculture.1522914 (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Impact of drought stress on yield-related agronomic traits of different genotypes in spring wheat. Agronomy 13, 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13122968 (2023).

Jumrani, K. & Bhatia, V. S. Identification of drought-tolerant genotypes using physiological traits in soybean. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 25, 697–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-019-00665-5 (2019).

Diack, O. et al. GWAS unveils features between early- and late-flowering pearl millets. BMC Genomics 21, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-07198-2 (2020).

Okoli, E. E. Exploitation of rank summation index for the selection of 21 maize hybrids for green maize production in South-eastern Nigeria. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. Discov. 6, 13–18 (2021).

Cabello, R., Monneveux, P., De Mendiburu, F. & Bonierbale, M. Comparison of yield-based drought tolerance indices in improved varieties, genetic stocks and landraces of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Euphytica 193, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-013-0887-1 (2013).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Multi-environment trials and stability analysis for yield-related traits of commercial rice cultivars. Agriculture 13, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13020256 (2023).

Mohammadi, R. Efficiency of yield-based drought tolerance indices to identify tolerant genotypes in durum wheat. Euphytica 211, 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-016-1727-x (2016).

Fischer, R. A. & Maurer, R. Drought resistance in spring wheat cultivars. I. Grain yield responses. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 29, 897–912. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9780897 (1978).

Rosielle, A. A. & Hamblin, J. Theoretical aspects of selection for yield in stress and non-stress environment. Crop Sci. 21, 943–946. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1981.0011183x002100060-033x (1981).

Bouslama, M. & Schapaugh, W. T. Stress tolerance in soybean. Part 1: Evaluation of three screening techniques for heat and drought tolerance. Crop Sci. 24, 933–937. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1984.0011183X002400050026x (1984).

Yadav, O. P. Drought response of pearl millet landrace-based populations and their crosses with elite composites. Field Crops Res. 118, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2010.04.005 (2010).

Sood, S., Bhardwaj, V., Kumar, V. & Gupta, V. K. BLUP and stability analysis of multi-environment trials of potato varieties in sub-tropical Indian conditions. Heliyon 6, e05525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05525 (2020).

Zuffo, A. M. et al. Multi-trait stability index: A tool for simultaneous selection of soybean genotypes in drought and saline stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 206, 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.12409 (2020).

Olivoto, T., Diel, M. I., Schmidt, D. & Lúcio, A. D. MGIDI: A powerful tool to analyze plant multivariate data. Plant Methods 18, 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-022-00952-5 (2022).

Volpato, L. et al. Inference of population effect and progeny selection via a multi-trait index in soybean breeding. Acta Sci. Agron. 43, e44623. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v43i1.44623 (2020).

Behera, P. P. et al. Genetic gains in forage sorghum for adaptive traits for non-conventional area through multi-trait-based stability selection methods. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1248663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1248663 (2024).

Singamsetti, A. et al. Genetic gains in tropical maize hybrids across moisture regimes with multi-trait-based index selection. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1147424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1147424 (2023).

Subramani, P. et al. Selection of superior and stable fodder maize hybrids using MGIDI and MTSI indices. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 24, e498624418. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-70332024v24n4a55 (2024).

Ghavidel, S., Pour-Aboughadareh, A. & Mostafavi, K. Identification of drought-tolerant genotypes of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) based on selection indices. Crop Sci. Res. Arid Reg. 5, 671–687. https://doi.org/10.2203/csrar.2024.371176.1294 (2024).

Ghazvini, H. et al. A framework for selection of high-yielding and drought-tolerant genotypes of barley: Applying yield-based indices and multi-index selection models. J. Crop Health 76, 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-024-00981-1 (2024).

Shapiro, S. S. & Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611 (1965).

Levene, H. Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics 278–292 (Stanford University Press, 1960).

Kay, M. & Wobbrock, J. ARTool: aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial ANOVAs. R package version 0.11, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.594511 (2021).

Kruskal, W. H. A nonparametric test for the several sample problem. Ann. Math. Stat. 23, 525–540 (1952).

Wickham, H. Data analysis. In ggplot: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 189–201, 2016.

Bezançon, G. et al. Changes in the diversity and geographic distribution of cultivated millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) varieties in Niger between 1976 and 2003. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 56, 223–236 (2009).

Dussert, Y., Snirc, A. & Robert, T. Inference of domestication history and differentiation between early- and late-flowering varieties in pearl millet. Mol. Ecol. 24, 1387–1402 (2015).

Wei, T. et al. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 56, e24 (2017).

Salson, M. et al. An improved assembly of the pearl millet reference genome using Oxford Nanopore long reads and optical mapping. G3 Bethesda 13, 051. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkad051 (2023).

Ramalingam, A. P. et al. Pilot-scale genome-wide association mapping in diverse sorghum germplasms identified novel genetic loci linked to major agronomic, root, and stomatal traits. Sci. Rep. 13, 21917. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48758-2 (2023).

Olivoto, T. et al. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials I: Combining features of AMMI and BLUP techniques. Agron. J. 111, 2949–2960. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.03.0220 (2019).

Olivoto, T. & Lúcio, A. D. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 11, 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13384 (2020).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using “Eigen” and S4. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.lme4 (2003).

Olivoto, T. & Nardino, M. MGIDI: A novel multi-trait index for genotype selection in plant breeding. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217778 (2020).

Falconer, D. S., Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. (Dep. Genet., Edinburgh Univ., UK, 1981)

Acknowledgements

This is a contribution from Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station KAES number 25−153-J. This is also part of the USDA-ARS National Program 215: Pastures, Forage and Rangeland Systems, as a co-author is now working for USDA-ARS. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the US Department of Agriculture or any part herein. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sabreena A. Parray: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing original draft. Ajay Prasanth Ramalingam and Midhat Z. Tugoo: Data collection and compilation; Desalegn D. Serba: material development and reviewing the draft manuscript. P. V. Vara Prasad: Conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; supervision; validation; visualization; and editing. Ramasamy Perumal: Conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; supervision; validation; visualization; writing and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parray, S.A., Ramalingam, A.P., Tugoo, M.Z. et al. Harnessing genetic diversity for drought tolerance and forage yield improvement in pearl millet germplasms through a prebreeding framework. Sci Rep 15, 40033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23884-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23884-1