Abstract

While previous investigations utilizing high-resolution satellite observations (e.g., Van Allen Probes) have elucidated the competition between radial diffusion and local wave-driven acceleration mechanisms during geomagnetic storms, the relative dominance of these processes under long geomagnetically quiet conditions (Kp = 2) remains poorly quantified. To address this gap, we utilize a three-dimensional radiation belt simulation model to resolve electron dynamics. Our study quantifies the comparative roles of radial diffusion and chorus wave-driven diffusion across long quiet time, incorporating two parameterized radial diffusion models and chorus wave diffusion coefficients. Simulations span electron energies of 300 keV–3 MeV and equatorial pitch angles of 30°–90°, reveal that radial diffusion is the dominant mechanism driving electron acceleration, particularly at lower L-shells and higher pitch angles, where flux peaks are more pronounced. Conversely, chorus wave-driven local diffusion primarily governs electron loss at lower pitch angles, while promoting acceleration at higher pitch angles. This study highlights the critical role of radial diffusion in shaping radiation belt electron dynamics during geomagnetic quiescence, with chorus waves playing a secondary but significant role. The findings underscore the need for improved parameterizations of radial diffusion models and provide a theoretical foundation for understanding the interactions between radiation belt electrons and space weather phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth’s radiation belts, toroidal regions encircling the planet, are characterized by populations of high-energy charged particles trapped by the geomagnetic field1,2. The inner belt is relatively stable, containing sub-MeV electrons, whereas the outer belt exhibits substantial dynamic variability in electron flux3. This variability is driven by a complex interplay of acceleration, loss, and transport mechanisms, making the understanding of high-energy electron production and evolution a central focus of radiation belt physics4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

Two primary mechanisms govern these processes: radial diffusion and local wave-particle interactions. Radial diffusion, induced by ultra-low-frequency (ULF) wave activity, results in the cross L-shell transport of electrons20,21. Local interactions, particularly those involving whistler-mode chorus waves, lead to electron acceleration and scattering via cyclotron resonance22,23,24,25. While both mechanisms are recognized as crucial, their relative contributions to electron acceleration and loss, particularly across different energy ranges and geomagnetic conditions, remain an area of active research.

Local diffusion by chorus waves violates the first and second adiabatic invariants, causing significant local acceleration and pitch-angle scattering, leading to both energization and loss to the atmosphere22,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Radial diffusion, conversely, violates the third adiabatic invariant, perturbing particle drift orbits33,34. Previous simulations relying solely on radial diffusion have often underestimated the rapid flux enhancements of high-energy electrons observed during geomagnetic storm recovery phases35,36,37. The inclusion of local diffusion, specifically driven by chorus waves, provides a more complete explanation for these rapid changes, highlighting the importance of wave-particle interactions.

Recent high-resolution observations from missions like the Van Allen Probes have provided unprecedented detail regarding radiation belt dynamics during specific geomagnetic events38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. For instance, analyses of the October 8–9, 2012, geomagnetic storm by Reeves et al.13 and Thorne et al.24 demonstrated the dominance of local acceleration via chorus wave-particle interactions in driving electron flux enhancements. These in situ measurements underscore the critical role of local diffusion in modulating electron flux variability.

However, the relative importance of radial versus local diffusion is known to be dependent on geomagnetic conditions. Three-dimensional simulations by Ma et al.38, comparing storm-time (March 17–19, 2013) and quiet-time (September 19–21, 2013) events, indicated a dominance of local diffusion during storms and radial diffusion during quiet periods. Further studies by Katsavrias et al.46 and Zhao et al.47 suggested an energy-dependent interplay: chorus waves initially accelerate “seed” electrons to relativistic energies, followed by further energization to ultra-relativistic energies via radial diffusion. This proposed two-step mechanism highlights a potential synergistic relationship. Theoretical investigations by Allison and Shprits48 and Allison et al.49, however, suggest that under conditions of low plasma density, chorus wave-driven local acceleration alone can directly accelerate electrons to ultra-relativistic energies.

Despite these advances, a comprehensive understanding of the relative contributions of radial and local diffusion to electron acceleration and loss during extended geomagnetically quiet periods, including their energy and pitch angle dependencies, remains incomplete. To address this critical knowledge gap, we present a detailed analysis of the interplay between these mechanisms during a prolonged period of geomagnetic quiescence (Kp = 2). Our approach combines parameterized radial diffusion models—specifically, the Brautigam and Albert35 (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\)) and Liu et al.50 (\(D_{{LL}}^{L}\)) models—with chorus wave local diffusion coefficients derived from the Zhang et al.51 database. By numerically solving the Fokker-Planck equation using a three-dimensional simulation code, we simulate electron evolution across a broad parameter space, encompassing energies from 300 keV to 3 MeV, pitch angles from 0° to 90°, and L-shells from 2 to 7. This comprehensive simulation allows us to disentangle the energy- and pitch-angle-dependent contributions of each mechanism, providing new insights into radiation belt dynamics during quiet-time conditions and contributing to improved space weather forecasting capabilities. Our findings reveal that, during these quiet periods, radial diffusion is the primary driver of electron acceleration, while chorus wave-driven local diffusion plays a secondary role. Conversely, electron loss is predominantly governed by local diffusion associated with chorus waves. The distinct energy- and pitch-angle-dependent interactions between these mechanisms are elucidated, offering a refined understanding of radiation belt dynamics.

Model and methods

Three-Dimensional diffusion model

This study employs the UCLA three-dimensional (3-D) diffusion code38 to simulate the evolution of electron phase space density (PSD) within Earth’s radiation belts. The code solves a modified form of the Fokker-Planck equation, which describes the temporal evolution of particle distributions under the influence of diffusive processes:

where, f denotes the electron phase space density (PSD), t represents the simulation time, µ, J, and L* are the first, second, and third adiabatic invariants (Adiabatic invariants are conserved quantities in charged particle periodic motion under slowly varying background magnetic fields, satisfying the adiabatic condition52, respectively. α is the electron equatorial pitch angle, <Dαα>, <Dαp> and < Dpp> are the bounce-averaged pitch angle, mixed (pitch angle, momentum), and momentum diffusion coefficients, respectively. These coefficients represent the effects of wave-particle interactions. <DL*L*> is the radial diffusion coefficient, representing transport across L-shells, while < DLL> is the radial diffusion coefficient assuming a dipole magnetic field. S(α) is a function related to the electron bounce period53, and τ denotes the bounce loss time, defined as one-quarter of the bounce period within the loss cone and infinite outside the loss cone.

The simulation domain spans L-shells from 2 to 7. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the adiabatic invariants (µ and K) and the corresponding particle energy and pitch angle. The momentum space boundaries are defined by 50 ≤ µ ≤ 100,000 MeV/G and K = 0, corresponding to electron energies ranging from 984 keV to 62.3 MeV at L = 2 and 43.2 keV to 9.1 MeV at L = 7. The pitch angle range extends from 0° to 90°. The computational grid consists of 121 energy cells, a radial resolution of ΔL = 0.25 and a pitch angle resolution of 1°. The inner boundary condition at L = 2 is set to f = 0. Following Shprits and Thorne54, a fixed outer boundary condition at L = 7 is imposed, derived from CRRES satellite measurements:

where E is the electron kinetic energy in MeV. The initial condition is the steady-state solution of the \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) model under quiet geomagnetic conditions (Kp = 2), given by:

The simulation is run for a duration of six days, assuming a dipolar geomagnetic field.

Chorus wave-driven diffusion coefficients

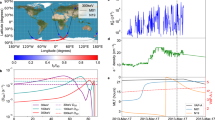

We simulate a geomagnetically quiet period with a constant Kp index of 2 (Fig. 2a, blue solid line). The plasmapause location (Lpp) is determined using the Carpenter and Anderson55 model:

Model parameters for the geomagnetically quiet period (Kp = 2). (a) Kp index (blue solid line) and calculated plasmapause location (Lpp) using the Carpenter and Anderson52 model (red dashed line). (b) Chorus wave amplitude (Bw) as a function of L-shell and magnetic local time (MLT), calculated using the Wang et al.54 model. (c) Background plasma density (Ne, cm−3) as a function of L-shell, calculated using the Sheeley et al.53 model (blue solid line).

This is represented by the red dashed line in Fig. 2a. The background plasma density is calculated using the Sheeley et al.56 electron density model (Fig. 2c). The plasma density inside the plasmapause is:

and outside the plasmapause:

The chorus wave diffusion coefficients are obtained from the Zhang et al.51 database. This database employs quasi-parallel chorus waves, and the wave spectrum follows a Gaussian distribution characterized by four key parameters: ωlc = 0.05|Ωe|, ωuc = 0.65|Ωe|, ωm = 0.35|Ωe|, δω = 0.15|Ωe|, where Ωe represents the electron cyclotron frequency. Linear interpolation is used to determine the coefficients based on L-shell and the calculated background plasma environment. The chorus wave amplitudes are calculated using the Wang et al.57 model, which provides low-frequency, equatorial chorus wave amplitudes for 21 L-shell grids and 24 magnetic local time (MLT) sectors (Fig. 2b). The interpolated diffusion coefficients are then scaled according to these wave amplitudes.

Figures 3, 4, and 5 present the scaled, bounce-averaged pitch angle diffusion coefficients (< Dαα>), momentum diffusion coefficients (< Dαp>), and mixed diffusion coefficients (< Dpp>) for L = 2, 4, 5, and 7, and MLT = 0, 6, 12, and 18. As evident in these figures, the chorus wave diffusion coefficients exhibit higher values in the region defined by 5 ≤ L ≤ 7 and 9 ≤ MLT ≥ 21, consistent with previous observations that high-latitude chorus waves are predominantly located outside the plasmapause on the nightside58,59.

Bounce-averaged pitch angle diffusion coefficients (< Dαα>) for chorus waves at Kp = 2, obtained by linear interpolation from the Zhang et al.49 database. Panels show coefficients for L = 2, 4, 5, and 7, and MLT = 0, 6, 12, and 18. The x-axis represents equatorial pitch angle (degrees), the y-axis represents electron energy (MeV), and the color scale indicates the diffusion coefficient magnitude.

Same as Fig. 3, but for the bounce-averaged momentum diffusion coefficients (< Dpp>).

Same as Fig. 3, but for the bounce-averaged mixed (pitch angle and momentum) diffusion coefficients (< Dαp>).

Radial diffusion coefficients

Several parameterized models for the radial diffusion coefficient (DLL) exist, including those developed by Brautigam and Albert35 (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\)), Ozeke et al.60 (\(D_{{LL}}^{O}\)), Liu et al.50 (\(D_{{LL}}^{L}\)), and Ali et al.61 (\(D_{{LL}}^{{\text{A}}}\)). The work of Drozdov et al.62 provides a baseline, showing that among five tested models, \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) was the top performer for long-term simulations. In contrast, Guo et al.44 showed in a three-dimensional storm simulation that \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) outperformed \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\). Therefore, in this study, we selected the two commonly used models in previous studies — \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) and \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) — to compare the differences in radiation belt electron evolution caused by the introduction of different radial diffusion coefficient models. The Brautigam and Albert’s35 model includes both electromagnetic (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAEM}}}}\)) and electrostatic (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAES}}}}\)) components. \(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAEM}}}}\) is derived from in situ measurements at L = 6.6 and ground-based magnetometer data at L = 463, expressed as a function of Kp:

The electrostatic term, \(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAES}}}}\), is a linear function of Kp35,64. However, previous studies65,66 have shown that including both components can lead to overestimation of electron fluxes in the slot region. Following established practice67, we exclude \(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAES}}}}\) and use only the electromagnetic component (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BAEM}}}}\)) in this study (Fig. 6, blue line):

Radial diffusion coefficients (DLL) as a function of L-shell. The blue solid line represents the \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) model33. The red solid line represents the \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) model48 for µ = 1000 MeV/G. The red shaded area encompasses the range of \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) values for µ = 400–8000 MeV/G. Units are day−1.

The Liu et al.50 model (Fig. 6, red region) is based on the electric field component (\({\text{D}}_{{LL}}^{{LE}}\)) derived using the method of Fei et al.68. They demonstrated that the electric field component is significantly larger than the magnetic field component, suggesting that radial diffusion is primarily driven by electric field fluctuations associated with ULF waves:

where \({\text{D}}_{{LL}}^{{LE}}\) is expressed as a function of Kp and µ, based on seven years of THEMIS satellite observations:

The \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) model is valid for 400 ≤ µ ≤ 8000 MeV/G. Figure 6 (red line) shows the diffusion coefficient for µ = 1000 MeV/G.

Results and analysis

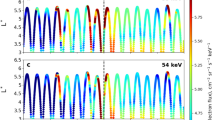

This section presents the results of our 3-D simulations, examining the evolution of seed (300 keV), relativistic (1 MeV), and ultra-relativistic (3 MeV) electrons under various diffusion mechanisms. We compare five simulation scenarios: (1) 1-D Radial Diffusion (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BA}}}}\) only): Simulations considering only radial diffusion using the Brautigam and Albert35 model. (2) 1-D Radial Diffusion (\(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) only): Simulations considering only radial diffusion using the Liu et al.50 model. (3) 2-D Local Diffusion (Chorus Waves only): Simulations considering only local diffusion due to chorus wave interactions. (4) 3-D Combined (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BA}}}}\) + Chorus): Simulations including both radial diffusion (\(D_{{LL}}^{{{\text{BA}}}}\)) and chorus wave local diffusion. (5) 3-D Combined (\(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) + Chorus): Simulations including both radial diffusion (\(D_{{LL}}^{L}\)) and chorus wave local diffusion. We analyze the simulated electron flux evolution for energies of 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV, and equatorial pitch angles of 30°, 60°, and 90°, to illustrate the relative contributions of each mechanism.

Evolution of 300 keV electrons

Figure 7 presents the temporal evolution of 300 keV electron flux for the five simulation scenarios. The 1-D radial diffusion simulations (Fig. 7a-c for \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\), and Fig. 7d-f for \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\)) show similar behavior. Using \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) as an example (Fig. 7a-c), we observe a gradual increase in electron flux across all pitch angles within the L-shell range of 4.5 to 6.5. The magnitude of this flux enhancement increases with pitch angle. At L = 5, after six days, the electron fluxes at 30°, 60°, and 90° increase from an initial value of 1.18e3 cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1 to 3.08e3, 3.73e3, and 4.02e3 cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1, respectively.

Simulated evolution of 300 keV electron flux (cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1) for different diffusion scenarios. Rows represent different simulation setups: (a-c) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\); (d-f) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\); (g-i) 2-D local diffusion with chorus waves; (j-l) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) and chorus waves; (m-o) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) and chorus waves. Columns represent different equatorial pitch angles: 30° (left), 60° (middle), and 90° (right). The x-axis represents simulation time (days), the y-axis represents L-shell, and the color scale indicates the electron flux.

The 2-D simulation, considering only chorus wave interactions (Fig. 7g-i), reveals a significant reduction in flux for 30° pitch angle electrons. At L = 5, the flux decreases from 1.18e3 to 730.11 cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1 after six days. For 60° and 90° pitch angles (Fig. 7h,i), the flux initially increases, peaking around day one, before subsequently decreasing. The peak flux increases with pitch angle, reaching 2.09e3 cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1 for 60° and 2.87e3 cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1 for 90°.

The 3-D simulations (Fig. 7j-l for \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) + Chorus, and Fig. 7m-o for \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) + Chorus) demonstrate that the combined effects of radial and local diffusion lead to electron acceleration across all pitch angles. Higher pitch angles consistently exhibit higher flux peaks.

Figure 8 presents the daily averaged flux of 300 keV electrons at a 90° pitch angle. Both radial diffusion models (Fig. 8a,b) show flux enhancements, peaking near L ≈ 5. Notably, \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) produces stronger acceleration at lower L-shells (L < 4) compared to \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\). The 2-D chorus wave simulation (Fig. 8c) shows an initial increase followed by a decrease in flux within the L-shell range of 4.75 to 7, peaking on day one. The 3-D simulations (Fig. 8d,e) exhibit the synergistic effect of chorus wave-driven acceleration and radial diffusion drove rapid electron flux enhancement within the initial 48 h.

Daily averaged flux (cm−2 sr−1 keV−1 s−1) of 300 keV electrons at a 90° equatorial pitch angle for different simulation days. (a) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\). (b) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\). (c) 2-D local diffusion with chorus waves. (d) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) and chorus waves. (e) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) and chorus waves. The x-axis represents L-shell, and the y-axis represents electron flux.

Evolution of 1 MeV electrons

Figure 9 illustrates the evolution of 1 MeV electron flux. The 1-D radial diffusion simulations (Fig. 9a-f) show electron acceleration across all pitch angles (30° to 90°). The 2-D chorus wave simulations (Fig. 9g-i) demonstrate electron loss at 30° pitch angle, but acceleration at 60° and 90°, with the peak flux increasing with pitch angle. The 3-D simulations (Fig. 9j-o) show acceleration at all pitch angles, with the combined effects of radial and local diffusion. The competition between inward radial diffusion and chorus wave pitch-angle scattering leads to a gradual increase in the 30° pitch angle electron flux (Fig. 9a, d, g, j, and m). For 60° and 90° pitch angles, both radial diffusion and chorus wave-induced energy diffusion contribute to enhanced electron acceleration. The flux peaks in the 3-D simulations are slightly higher than those in the 1-D and 2-D simulations.

Same as Fig. 7, but for 1 MeV electrons.

Figure 10 shows the daily averaged flux of 1 MeV electrons at a 90° pitch angle. Both radial diffusion (Fig. 10a,b) and chorus wave driven energy diffusion (Fig. 10c) contribute to electron acceleration, but operate in spatially distinct regions. Radial diffusion predominantly accelerates electrons in the L = 3.5–5.5 region, with flux peaking at L = ~ 4.6. In contrast, chorus waves drive acceleration primarily at L = 5–7, exhibiting maximum flux near L = ~ 5.5. The 3-D simulations (Fig. 10d,e) show the combined effect, resulting in even higher flux peaks at L = ~ 5.

Same as Fig. 8, but for 1 MeV electrons.

Evolution of 3 MeV electrons

Figure 11 presents the evolution of 3 MeV electron flux. The 1-D radial diffusion simulations (Fig. 11a-f) show effective electron acceleration across all pitch angles, with flux peaks near L ≈ 4.5. The 2-D chorus wave simulations (Fig. 11g-i) show acceleration for 30°–60° pitch angles, but a loss of electrons at 90°. The 3-D simulations (Fig. 11j-o) demonstrate acceleration across all pitch angles. Inward radial diffusion and chorus wave driven energy diffusion jointly promote the acceleration of 30°–60° pitch angle electrons. The electron flux in the 3-D simulations is significantly higher than in the 2-D simulations and comparable to the 1-D simulations, indicating that radial diffusion dominates the acceleration of 30°–60° pitch angle electrons. For 90° pitch angle electrons, the competing effects of radial diffusion-driven acceleration (Fig. 11c,f) and chorus wave pitch-angle scattering-induced loss (Fig. 11i) result in a net increase in electron flux (Fig. 11l,o).

Same as Fig. 7, but for 3 MeV electrons.

Figure 12 shows the daily averaged flux of 3 MeV electrons at a 90° pitch angle. Radial diffusion (Fig. 12a,b) accelerates electrons, while local diffusion with only chorus waves (Fig. 12c) results in a slight flux decrease. The 3-D simulations (Fig. 12d,e) exhibit increased electron flux, with the peak magnitude matching that of the radial-diffusion-only case.

Same as Fig. 8, but for 3 MeV electrons.

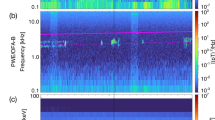

Comparative analysis of flux evolution

To provide a quantitative comparison of electron evolution under different mechanisms, we calculate the ratio of the electron flux after six days of simulation to the initial flux:

Figure 13 presents these flux ratios. A ratio of 1 (white) indicates no net change; a ratio greater than 1 (red) indicates net acceleration; and a ratio less than 1 (blue) indicates net loss.

Ratio of electron flux after six days of simulation to the initial electron flux, illustrating the net effect of different diffusion mechanisms. (a-c) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (d-f) 1-D radial diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (g-i) 2-D local diffusion with chorus waves for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (j-l) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) and chorus waves for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (m-o) 3-D combined diffusion with \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) and chorus waves for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. The x-axis represents L-shell, the y-axis represents equatorial pitch angle (degrees), and the color scale indicates the flux ratio.

The 1-D radial diffusion simulations (Fig. 13a-f) show significant acceleration of 300 keV–3 MeV electrons with in the L-shell range 2–5. At L > ~ 5, electrons with energies ranging from 300 keV to 3 MeV are more easily accelerated at high pitch angles, while at low pitch angles, the acceleration effect is not obvious and they may even be lost through radial diffusion outward.

The 2-D chorus wave simulations (Fig. 13g-i) show that outside the plasmasphere, chorus waves scatter 300 keV electrons (Fig. 13g), and the lower the pitch angle, the easier they are to be scattered. For 1 MeV electrons (Fig. 13h), chorus waves accelerate electrons at moderate and high pitch angles (> 30°) and scatter those at low pitch angles (< 30°). For 3 MeV electrons (Fig. 13i), chorus waves accelerate electrons with pitch angles between 15° and 75°, while scattering electrons near the loss cone and those with pitch angles between 75° and 90°.

The 3-D simulations (Fig. 13j-o) show that inside the plasmasphere (L < ~ 4.5) and outside the loss cone, electrons are accelerated across the energy range of 300 keV to 3 MeV. Outside the plasmasphere (L > ~ 4.5), electrons with energies of 300 keV–3 MeV and high pitch angles (> 30°) are accelerated, while those with low pitch angles (< 30°) are lost.

Specifically, for 300 keV electrons (Fig. 13a, d, g, j, and m), 1-D simulations show an increase in flux outside the loss cone. 2-D simulations show a decrease. 3-D simulations show an increase flux at moderate and high pitch angles (> 30°) and a decrease at low pitch angles (< 30°). At moderate and high pitch angles, the competing effects of inward radial diffusion and chorus wave pitch-angle scattering result in a net increase in flux. At low pitch angles (< 30°), the competition results in a net decrease in flux. Inside the plasmapause, radial diffusion is the sole process present. Consequently, electron acceleration in this region is primarily driven by radial diffusion. Outside the plasmapause, however, competition exists between inward radial diffusion and chorus wave pitch angle scattering. Therefore, acceleration of medium-to-high pitch angle (~ 30°–90°) electrons is primarily governed by inward radial diffusion, whereas loss of low pitch angle (< ~ 30°) electrons is dominated by chorus wave scattering. A similar analytical approach was applied to 1 MeV (Fig. 13b, e, h, k, and n) and 3 MeV (Fig. 13c, f, i, l, and o) electrons.

Relative contributions of radial and local diffusion

To compare the contributions of radial and local diffusion in the 3-D simulations, we calculate the ratios of the electron flux from the 1-D and 2-D simulations to the electron flux from the 3-D simulations after six days (Fig. 14). Figure 14a-f show the ratios of the 1-D simulation results (radial diffusion only) to the 3-D simulation results. Figure 14g-l show the ratios of the 2-D simulation results (chorus wave local diffusion only) to the 3-D simulation results. A ratio of 1 (white) indicates that the 1-D (or 2-D) simulation results are comparable to the 3-D results. A ratio greater than 1 (red) indicates that the 1-D (or 2-D) simulation results are higher than the 3-D results. A ratio less than 1 (blue) indicates that the 1-D (or 2-D) simulation results are lower than the 3-D results. Figure 14a-f show that the ratio of the 1-D simulation results to the 3-D simulation results is close to 1 across most of the parameter space, indicating that radial diffusion is the dominant mechanism during quiet geomagnetic periods. Figure 14g-l show that the ratio of the 2-D simulation results to the 3-D simulation results is generally less than 1, suggesting that chorus wave local diffusion alone underestimates the electron acceleration. The dominant mechanisms governing electron acceleration or loss across different pitch-angle ranges and spatial regions are detailed in Table 1.

Comparison of electron flux ratios after six days of simulation, highlighting the relative contributions of radial and local diffusion. (a-c) Ratio of 1-D radial diffusion (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) only) flux to 3-D combined (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) + Chorus) flux for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (d-f) As in (a-c), but for the \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) model. (g-i) Ratio of 2-D local diffusion (Chorus only) flux to 3-D combined (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) + Chorus) flux for 300 keV, 1 MeV, and 3 MeV electrons, respectively. (j-l) As in (g-i), but for the \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\) model. The x-axis represents L-shell, the y-axis represents equatorial pitch angle (degrees), and the color scale indicates the flux ratio.

Therefore, our results indicate that during quiet geomagnetic periods, the evolution of 300 keV−3 MeV electrons is primarily governed by radial diffusion, with chorus waves playing a secondary, but still important, role in local diffusion and pitch-angle scattering. This finding aligns with the simulation results of Ma et al.40 for quiet-time conditions.

Conclusions

This study investigated the relative contributions of radial diffusion and local chorus wave interactions to the evolution of radiation belt electrons during geomagnetically quiet conditions. We employed a three-dimensional (3-D) diffusion model, incorporating two parameterized radial diffusion models (\(D_{{LL}}^{{BA}}\) and \(D_{{LL}}^{L}\)) and chorus wave diffusion coefficients derived from the Zhang et al.51 database. By comparing 1-D (radial diffusion only), 2-D (chorus wave diffusion only), and 3-D (combined) simulations, we quantified the effects of these mechanisms on electron acceleration and loss across a range of energies (300 keV to 3 MeV) and pitch angles (0° to 90°).

Our principal findings are summarized as follows:

(1) Dominant Mechanism by Pitch Angle: For Low PA (e.g., 30°–60°), Electrons in this range are highly susceptible to cyclotron resonance with chorus waves, resulting in potent local acceleration. For High PA (e.g., > 70°), local acceleration becomes less efficient, while pitch-angle scattering by chorus waves—which drives precipitation loss—becomes the dominant local process. At the same time, radial diffusion is most effective at transporting and energizing electrons near 90° PA.

(2) The Acceleration-to-Loss Transition: At a fixed L-shell and energy, an electron at low PA experiences strong local acceleration. As its pitch angle increases, that local acceleration wanes, and local scattering (loss) grows stronger. The transition (the point where the net effect of these competing processes flips from positive to negative) occurs when the rate of loss from pitch-angle scattering surpasses the combined rate of acceleration from local energy diffusion and inward radial transport. This explains why we often see acceleration at low pitch angles and concurrent loss at high pitch angles.

(3) Energy and L-shell Dependencies: These dependencies are driven by the resonance conditions and spatial distributions of the waves. The local acceleration is strongest where the chorus wave power is highest (typically L ~ 4–6) and for energies that efficiently resonate with those waves (hundreds of keV to low MeV). Outside these regions/energies, local processes become weaker, allowing radial diffusion or loss to dominate.

In conclusion, our simulation-based study elucidates the dynamics of the outer radiation belt during extended geomagnetic quiescence. The results indicate that the belt exists in a state of dynamic equilibrium, primarily governed by the slow, continuous energization of electrons via radial diffusion. While local acceleration driven by chorus waves constitutes a secondary source, its contribution is non-negligible, particularly for electrons in specific energy and pitch-angle regimes. A key implication of this dynamic equilibrium relates to the initialization of space weather prediction models. The accuracy of these models is often limited by the fidelity of their initial conditions for pre-storm electron distributions. Our work demonstrates that a physically-driven simulation incorporating the continuous competition between radial transport and local wave interactions provides a more realistic quiet-time baseline than a static or averaged state, thereby offering a path to enhanced forecast accuracy. It is important to contextualize our findings within the scope of our model. The exclusion of significant loss processes, namely scattering by plasmaspheric hiss and EMIC waves, means our simulated electron fluxes likely represent an upper limit38,69,70. These mechanisms are known to be highly effective at removing electrons within the plasmasphere and at relativistic energies, respectively. Furthermore, the quantitative results are sensitive to our model inputs. The use of a steady Kp = 2 is an idealization, as natural variability would modulate both chorus and ULF wave power. Likewise, the plasma density model is a key determinant of the local diffusion rates and remains a significant source of uncertainty across the community.

Based on these findings and limitations, future work should proceed along two complementary paths. Computationally, the next step is to advance from idealized scenarios to long-term, data-driven simulations that span both quiet and storm intervals, clarifying how the quiet-time equilibrium preconditions the magnetosphere for storm-time dynamics. Such a framework should also incorporate ensemble simulations to rigorously quantify model sensitivity to uncertainties in plasma density and wave activity. Observationally, this study reinforces the need for comprehensive, multi-point missions capable of capturing simultaneous measurements of ULF waves, chorus waves, and electron populations. These datasets would provide the ultimate ground truth for validating and distinguishing between competing physical mechanisms in next-generation models.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Van Allen, J. A. & Frank, L. A. Radiation around the Earth to a radial distance of 107, 400 Km. Nature 183, 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1038/183430a0 (1959).

Ebihara, Y., & Miyoshi, Y. Dynamic Inner Magnetosphere: A Tutorial and Recent Advances. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0501-2_9 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2011).

Reeves, G. D. et al. Energy-dependent dynamics of KeV to MeV electrons in the inner zone, outer zone, and slot regions. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 121, 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JA021569 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Dynamic responses of outer radiation belt electron phase space densities to geomagnetic storms: A statistical analysis based on Van Allen probes observations. Space Weather 22, e2024SW004038. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024SW004038 (2024).

Baker, D. N. et al. An extreme distortion of the Van Allen belt arising from the ‘Hallowe’en’ solar storm in 2003. Nature 432, 878–881. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03116 (2004).

Baker, D. N. et al. Multiyear measurements of radiation belt electrons: Acceleration, Transport, and loss. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 124, 2588–2602. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026259 (2019).

Behailu, G., Nigussie, M., Reeves, G. D. & Wing, S. Driving parameters for Multi-MeV electrons flux variations in outer radiation belt. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e2021JA029625. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JA029625 (2021).

Borovsky, J. E. & Denton, M. H. Differences between CME-driven storms and CIR-driven storms. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 111. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JA011447 (2006).

Hua, M., Bortnik, J. & Ma, D. Dependence of electron flux dropouts in the earth’s outer radiation belt on energy and driving parameters during geomagnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031882. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA031882 (2023).

Ni, B. et al. Origins of the earth’s diffuse auroral precipitation. Space Sci. Rev. 200, 205–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-016-0234-7 (2016).

Ni, B. et al. Artificial modification of earth’s radiation belts by ground-based very-low-frequency (VLF) transmitters. Sci. China Earth Sci. 65, 391–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-021-9850-7 (2022).

Pinto, V. A. et al. Radial response of outer radiation belt relativistic electrons during enhancement events at geostationary orbit. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027660. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027660 (2020).

Reeves, G. D. et al. Electron acceleration in the heart of the Van Allen radiation belts. Science 341, 991–994. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1237743 (2013).

Ripoll, J. F. et al. Reproducing the observed energy-dependent structure of earth’s electron radiation belts during storm recovery with an event-specific diffusion model. Geophys Res Lett. 43, 5616–5625. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL068869 (2016).

Su, Z. et al. Ultra-low-frequency wave-driven diffusion of radiation belt relativistic electrons. Nat. Commun. 6, 10096. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10096 (2015).

Turner, D. L., Shprits, Y., Hartinger, M. & Angelopoulos, V. Explaining sudden losses of outer radiation belt electrons during geomagnetic storms. Nat. Phys. 8, 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2185 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Prompt enhancements of radiation belt electrons over a wide energy range based on phase space density variations: A detailed case study. Astrophys. J. 942, 30. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aca4c7 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. The evolutions of the seed and relativistic electrons in the earth’s outer radiation belt during the geomagnetic storms: A statistical study. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031284. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA031284 (2023).

Xiong, Y. et al. Responses of relativistic electron fluxes in the outer radiation belt to geomagnetic storms. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 120, 9513–9523. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JA021440 (2015).

Schulz, M. & Eviatar, A. Diffusion of equatorial particles in the outer radiation zone. J. Geophys. Res. 74, 2182–2192. https://doi.org/10.1029/JA074i009p02182 (1969).

Green, J. C. & Kivelson, M. G. Relativistic electrons in the outer radiation belt: differentiating between acceleration mechanisms. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 109. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JA010153 (2004).

Horne, R. B. & Thorne, R. M. Potential waves for relativistic electron scattering and stochastic acceleration during magnetic storms. Geophys Res Lett. 25, 3011–3014. https://doi.org/10.1029/98GL01002 (1998).

Summers, D., Thorne, R. M. & Xiao, F. Relativistic theory of wave-particle resonant diffusion with application to electron acceleration in the magnetosphere. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 103, 20487–20500. https://doi.org/10.1029/98JA01740 (1998).

Thorne, R. M. et al. Rapid local acceleration of relativistic radiation-belt electrons by magnetospheric chorus. Nature 504, 411–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12889 (2013).

Ma, D., Bortnik, J., Ma, Q., Hua, M. & Chu, X. Simulating the earth’s outer radiation belt electron fluxes and their upper limit: A unified Physics-Based model driven by the AL index. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109169. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL109169 (2024).

Horne, R. B. & Thorne, R. M. Relativistic electron acceleration and precipitation during resonant interactions with whistler-mode chorus. Geophys Res Lett. 30. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL016973 (2003).

Roth, I., Temerin, M. & Hudson, M. K. Resonant enhancement of relativistic electron fluxes during geomagnetically active periods. Ann. Geophys. 17, 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00585-999-0631-2 (1999).

Summers, D. & Ma, C. -y. A model for generating relativistic electrons in the earth’s inner magnetosphere based on gyroresonant wave-particle interactions. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 105, 2625–2639. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JA900444 (2000).

Albert, J. M. Evaluation of quasi-linear diffusion coefficients for EMIC waves in a multispecies plasma. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 108. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JA009792 (2003).

Albert, J. M. Evaluation of quasi-linear diffusion coefficients for Whistler mode waves in a plasma with arbitrary density ratio. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 110. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JA010844 (2005).

Albert, J. M. Using quasi-linear diffusion to model acceleration and loss from wave-particle interactions. Space Weather. 2 https://doi.org/10.1029/2004SW000069 (2004).

Albert, J. M. Nonlinear interaction of outer zone electrons with VLF waves. Geophys Res Lett. 29, 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL013941 (2002).

Fälthammar, C. G. Effects of time-dependent electric fields on geomagnetically trapped radiation. J. Geophys. Res. 70, 2503–2516. https://doi.org/10.1029/JZ070i011p02503 (1965).

Fälthammar, C. G. On the transport of trapped particles in the outer magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 71, 1487–1491. https://doi.org/10.1029/JZ071i005p01487 (1966).

Brautigam, D. H. & Albert, J. M. Radial diffusion analysis of outer radiation belt electrons during the October 9, 1990, magnetic storm. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 105, 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JA900344 (2000).

Miyoshi, Y. S. et al. Observations and modeling of energetic electron dynamics during the October 2001 storm. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 111. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JA011351 (2006).

Albert, J. M., Meredith, N. P. & Horne, R. B. Three-dimensional diffusion simulation of outer radiation belt electrons during the 9 October 1990 magnetic storm. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 114. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JA014336 (2009).

Ma, Q. et al. Modeling inward diffusion and slow decay of energetic electrons in the earth’s outer radiation belt. Geophys Res Lett. 42, 987–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL062977 (2015).

Ma, Q. et al. Diffusive transport of several hundred keV electrons in the earth’s slot region. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 122, 10.235–10.246. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JA024452 (2017).

Ma, Q. et al. Quantitative evaluation of radial diffusion and local acceleration processes during GEM challenge events. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 123, 1938–1952. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JA025114 (2018).

Drozdov, A. Y., Shprits, Y. Y., Aseev, N. A., Kellerman, A. C. & Reeves, G. D. Dependence of radiation belt simulations to assumed radial diffusion rates tested for two empirical models of radial transport. Space Weather. 15, 150–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016SW001426 (2017).

Hua, M. et al. Modeling the electron flux enhancement and butterfly pitch angle distributions on L Shells < 2.5. Geophys Res Lett. 46, 10967–10976. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084822 (2019).

Lejosne, S. et al. Differentiating between the leading processes for electron radiation belt acceleration. Front. Astronomy Space Sci. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2022.896245 (2022).

Guo, D. et al. Three-dimensional simulations of ultra-relativistic electron acceleration during the 21 April 2017 storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031407. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA031407 (2023).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Simulating Long-Term dynamics of radiation belt electrons using DREAM3D model. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 129, e2023JA032286. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA032286 (2024).

Katsavrias, C., Daglis, I. A. & Li, W. On the statistics of acceleration and loss of relativistic electrons in the outer radiation belt: A superposed epoch analysis. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 124, 2755–2768. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA026569 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. On the acceleration mechanism of ultrarelativistic electrons in the center of the outer radiation belt: A statistical study. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 124, 8590–8599. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027111 (2019).

Allison, H. J. & Shprits, Y. Y. Local heating of radiation belt electrons to ultra-relativistic energies. Nat. Commun. 11, 4533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18053-z (2020).

Allison, H. J., Shprits, Y. Y., Zhelavskaya, I. S., Wang, D. & Smirnov, A. G. Gyroresonant wave-particle interactions with chorus waves during extreme depletions of plasma density in the Van Allen radiation belts. Sci. Adv. 7, eabc0380. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc0380 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. On the calculation of electric diffusion coefficient of radiation belt electrons with in situ electric field measurements by THEMIS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL067398 (2016).

Zhang, Q. Y., Ma, X., Guo, D. Y., Fu, S. & Ni, B. B. Multi-dimensional modeling of the diffusionrates of radiation belt electrons by whistle-mode chorus waves and simulations of resultant radiation belt electron loss timescales. Chin. J. Geophys. (in Chinese). 67, 1679–1698. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2023R0548 (2024).

Baumjohann, W. & Treumann, R. A. Basic Space Plasma physics. https://doi.org/10.1142/p850 (1997).

Lenchek, A. M., Singer, S. F. & Wentworth, R. C. Geomagnetically trapped electrons from cosmic ray albedo neutrons. J. Geophys. Res. (1896–) 66, 4027–4046.) 66, 4027–4046. (1977). https://doi.org/10.1029/JZ066i012p04027 (1961).

Shprits, Y. Y. & Thorne, R. M. Time dependent radial diffusion modeling of relativistic electrons with realistic loss rates. Geophys Res Lett. 31. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL019591 (2004).

Carpenter, D. L. & Anderson, R. R. An ISEE/whistler model of equatorial electron density in the magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 97, 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1029/91JA01548 (1992).

Sheeley, B. W., Moldwin, M. B., Rassoul, H. K. & Anderson, R. R. An empirical plasmasphere and trough density model: CRRES observations. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 106, 25631–25641. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JA000286 (2001).

Wang, D. & Shprits, Y. Y. On how High-Latitude chorus waves tip the balance between acceleration and loss of relativistic electrons. Geophys Res Lett. 46, 7945–7954. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082681 (2019).

Meredith, N. P., Horne, R. B., Shen, X. C., Li, W. & Bortnik, J. Global model of Whistler mode chorus in the near-equatorial region (|λm| < 18°). Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087311. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087311 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Analytical chorus wave model derived from Van Allen probe observations. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 124, 1063–1084. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026183 (2019).

Ozeke, L. G., Mann, I. R., Murphy, K. R., Rae, J., Milling, D. K. & I. & Analytic expressions for ULF wave radiation belt radial diffusion coefficients. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 119, 1587–1605. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JA019204 (2014).

Ali, A. F. et al. Electric and magnetic radial diffusion coefficients using the Van Allen probes data. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 121, 9586–9607. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JA023002 (2016).

Drozdov, A. Y., Allison, H. J., Shprits, Y. Y., Elkington, S. R. & Aseev, N. A. A comparison of radial diffusion coefficients in 1-D and 3-D Long-Term radiation belt simulations. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 126, e2020JA028707. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA028707 (2021).

Lanzerotti, L. J. & Morgan, C. G. ULF geomagnetic power near L = 4: 2. Temporal variation of the radial diffusion coefficient for relativistic electrons. J. Geophys. Res. (1896–) 78, 4600–4610.) 78, 4600–4610. (1977). https://doi.org/10.1029/JA078i022p04600 (1973).

Cornwall, J. M. Diffusion processes influenced by Conjugate-Point wave phenomena. Radio Sci. 3, 740–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/rds196837740 (1968).

Kim, K. C., Shprits, Y., Subbotin, D. & Ni, B. Understanding the dynamic evolution of the relativistic electron slot region including radial and pitch angle diffusion. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JA016684 (2011).

Ozeke, L. G. et al. ULF wave derived radiation belt radial diffusion coefficients. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 117. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JA017463 (2012).

Glauert, S. A., Horne, R. B. & Meredith, N. P. Simulating the earth’s radiation belts: internal acceleration and continuous losses to the magnetopause. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 119, 7444–7463. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JA020092 (2014).

Fei, Y., Chan, A. A., Elkington, S. R. & Wiltberger, M. J. Radial diffusion and MHD particle simulations of relativistic electron transport by ULF waves in the September 1998 storm. J Geophys Res Space Phys. 111. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JA011211 (2006).

Drozdov, A. Y. et al. Energetic, relativistic, and ultrarelativistic electrons: comparison of long-term VERB code simulations with Van Allen probes measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 120, 3574–3587. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JA020637 (2015).

Drozdov, A. Y. et al. Depletions of multi-MeV electrons and their association to minima in phase space density. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097620. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL097620 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their assistance in evaluating this paper. This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42188101, 42174188, 42474217, 42330207, 42025404, and 42204160), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF0503700 and 2022YFF0503900), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 242025kf0008), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (Grant No. 2025AFA030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q. Y. Z, S. F., X. M. & B. B. N.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; Q. Z., Y. Q. L., & T. F. J.: formal analysis; W. X. C., J. H. W., Y. B. Z., X. Y. T., Y. L., K. K. X. & D. F. Z.: data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Fu, S., Ma, X. et al. Competing mechanisms of radial and local diffusion in radiation belt electron dynamics during quiet-geomagnetic conditions. Sci Rep 15, 40038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23908-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23908-w