Abstract

This study aims to investigate the correlation between tensile mechanical properties and chemical composition of Hippophae rhamnoides roots at different growth stages within tailings dam restoration areas, and to establish predictive models. 1-year-old, 4-year-old, and 10-year-old H. rhamnoides root systems were selected as study subjects. Through single-root tensile tests and chemical composition analysis, principal component parameters were extracted using partial least squares regression (PLSR). Combined with support vector machine (SVM) for dimensionality reduction training, a PLSR-SVM prediction model was constructed. Accuracy comparison analysis was conducted on four different prediction models.Analysis of the correlation between tensile properties and chemical composition, along with model predictions, indicates: (1) Relationship between tensile properties and age: Both the average tensile force and tensile strength of H. rhamnoides root exhibit a decreasing trend with increasing age. Regarding size effects, root tensile force follows a power-law growth pattern with increasing root diameter, while tensile strength demonstrates a power-law decay characteristic. Distinct elastic-plastic characteristics are evident in individual root stress-strain curves. Root diameter at different ages shows a negative correlation with ultimate stress, independent of strain. (2) Correlation between tensile properties and chemical composition: The tensile strength of H. rhamnoides at different ages was significantly negatively correlated with lignin content and highly significantly positively correlated with root diameter; the tensile strength was significantly positively correlated with lignin content and highly significantly negatively correlated with root diameter. The tensile properties of H. rhamnoides at different ages were significantly different from each component of the root system, and the single chemical component content could not fully explain the size effect between root diameter and tensile properties. (3) Predictive performance of models linking tensile properties to chemical composition: The PLSR-SVM model demonstrated optimal overall performance in predicting tensile properties, with the evaluated error metrics significantly outperforming traditional the principal component analysis (PCA) model, the back propagation neural network (BP) model, the PLSR model, and the SVM model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hippophae rhamnoides, a typical drought-tolerant shrub of the Elaeagnaceae family in China’s arid regions, possesses advantages of cold resistance, drought tolerance, and adaptability to infertile soils. Its dense thickets, extensive root systems, and strong ability to produce suckers play a vital role in ecological projects such as soil and water conservation and slope stabilisation1,2. Globally, there are over 200,000 tailings ponds, with China alone hosting approximately 12,000 such facilities, accumulating a staggering two billion tonnes of tailings3.Tailings exhibit distinctive properties including poor particle grading, low water retention capacity, and high heavy metal toxicity. These characteristics constrain plant root growth and suppress microbial activity, rendering ecological stabilisation outcomes difficult to predict. Consequently, research into tailings ecological remediation presents a natural challenge for geotechnical and mine restoration practitioners. As a prototypical pioneer species for tailings ecological restoration, H. rhamnoides has found extensive application in slope protection and soil improvement projects within tailings pond environments.

Plant root systems play a pivotal role in restoring soil structure within tailings areas4,5, enhancing both soil stability5 and slope stability6. When soil is disturbed, plant roots convert shear stress, thereby demonstrating their tensile properties7. Research indicates that the tensile mechanical properties of roots are influenced by plant chemical composition7,8,9. Consequently, investigating the correlation between the tensile characteristics of plant roots in tailings areas and their chemical constituents has emerged as a research focus at the intersection of plant physiology, plant mechanics, and biochemistry. Huang et al.10 proposed that the cellulose and lignin ratios in herbaceous plants within landslide-prone areas significantly impact root mechanical properties.Hu et al.11 discovered significant differences in cellulose content between primary and lateral root segments, with a correlation to tensile properties. Genet12 categorised roots into coarse and fine types, observing distinct mechanical properties between them, with higher cellulose content in fine roots.Soippa et al.13 and Zhang et al.14 established that lignin within root chemistry exerts the most pronounced effect on root tensile strength. However, few studies have addressed the mechanisms linking root diameter, chemical composition, and tensile properties in plants growing in tailings areas. Particularly scarce are reports on predictive models correlating tensile characteristics with chemical composition.

The advancement of computing has facilitated the application of intelligent predictive models in geotechnical engineering and ecological restoration, with nonlinear fitting and multidimensional computation providing enhanced predictive capabilities15,16. However, different models possess distinct advantages and disadvantages. Wan et al.17 employed the back propagation neural network (BP) for nonlinear training of concrete fibre content factors. Yet, the presence of multicollinearity within the sample led to issues such as relatively high relative errors in predicting concrete mechanical properties18. Mao et al.19 employed principal component analysis (PCA) to investigate the distribution characteristics, source identification, and ecological risk factors of eight extracted heavy metals, subsequently applying positive matrix factorisation (PMF) to address PCA’s limitations in spatial heterogeneity20. Bin21 employed partial least squares regression (PLSR) to address multicollinearity issues in loess slope stability factors. However, the model exhibited limited nonlinear convergence capability between variables and slope safety factors, thereby compromising stability assessment accuracy. Yang et al.22 employed support vector machines (SVM) to analyse nonlinear residual sequences of dam deformation data. While capable of handling nonlinear relationships, the model failed to account for causal relationships between environmental variables and effect quantities, resulting in reduced model accuracy.

Research into the mechanisms linking plant root chemical composition to tensile properties has predominantly focused on plants in forested and cultivated soils, with scant attention directed towards mine tailings soils. Studies examining the chemical properties of H. rhamnoides, a key plant species in mine ecological restoration, remain scarce. Few investigations have explored the influence of mechanical properties through the lens of plant chemical composition structures, and the application of the PLSR-SVM coupled method in mine restoration has yet to be reported. Consequently, the following questions require resolution in tailings environments: (1) How do tensile properties vary across root age groups? (2) What correlation exists between lignin/cellulose content and tensile strength? (3) What factors account for tensile strength differences among roots of varying diameters? (4) How can conventional models be adapted to predict root characteristics within the complex tailings environment? Consequently, this study establishes a PLSR-SVM model correlating root chemical composition with tensile properties. This quantitative analysis of root chemical content and tensile strength provides predictive modelling support and scientific reference for selecting plants for tailings ecological restoration and evaluating root tensile characteristics.

Research content and methodology

Material collection

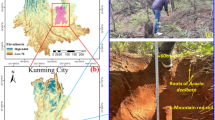

The sampling site for the test material is the second-class valley-type tailing pond at Crooked Head Mountain, part of the Bensteel Group. The shrub H. rhamnoides is a typical species in the ecological restoration area on the outer slope of the tailing dam. The study is in line with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research on Endangered Species and the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). After obtaining a permit to collect H. rhamnoide in the tailings area from the Bensteel Group, specimens were collected from H. rhamnoides plants of restoration ages 1-year-old, 4-year-old, and 10-year-old for the three terraces of the tailings pond (labeled A to C in sequence).The locations of the field sampling sites are shown in Fig. 1. In July 2023, we selected 16 to 20 sample plots on the three steps of the tailings dam, clearing away dead debris and weeds. Referring to the methods of Delory et al.23, Yang et al.24 and Wang et al.25, Liaoning nonferrous metals survey and Research Institute, an authoritative CMA testing institution recognized by the national certification and accreditation supervision committee, was entrusted to test the plant height, crown width and ground diameter of H. rhamnoides. The mean plant height (92.63 ± 17.83) cm, crown spread (85.06 ± 17.07) cm, and ground diameter (1.28 ± 0.21) mm for 1-year-old H. rhamnoides. Mean plant height (135.31 ± 18.80) cm, crown spread (107.63 ± 15.44) cm, ground diameter (1.80 ± 0.29) mm for 4-year-old H. rhamnoides.The mean plant height (322.50 ± 74.10) cm, crown spread (212.75 ± 79.90) cm, and ground diameter (4.48 ± 1.45) mm for 10-year-old H. rhamnoides, and the above were used as the standard plant data for the three steps. Using the full excavation method for collection, roots exhibiting straight growth and normal development were selected and brought back to the laboratory. Surface soil was gently brushed off to avoid mechanical damage. After thorough cleaning, the roots were stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator for subsequent experiments.The root systems of H. rhamnoides at different ages in the tailings area, as shown in Fig. 2.The Voucher specimens were stored in the botanical specimen room of the experimental center of Liaoning Nonferrous Survey Research Institute, which is recognized by the National Accreditation and Supervision Commission as an authoritative CMA testing institution.

The map of situ sampling. Google Earth image snippets of the area (https://www.google.com/earth/) show the location of the study area Crooked Head Mountain, part of the Bensteel Group in Liaoning Province, China.

Test preparation and tensile test methods

The diameter of H. rhamnoides root was measured using electronic vernier calipers, with the diameter of the root section expressed as the average value D (mm) at three equal points. Different ages of H. rhamnoides were classified statistically by diameter into 1 (0.5 < D ≤ 1 mm), 2 (1 < D ≤ 1.5 mm), 3 (1.5 < D ≤ 2 mm), 4 (2 < D ≤ 3 mm), 5 (3 < D ≤ 5 mm), and 6 (5 < D ≤ 10 mm) diameter classes. Root tensile strength was measured using a microcomputer-controlled electronic universal testing machine with a maximum capacity of 100 kN, a scale distance of 100 mm, and a tensile speed of 10 mm/min, with the test procedure duly recorded.

Methods of chemical composition determination

After determining the tensile properties, root samples were classified by diameter for chemical composition testing.The test method was based on the Van’s detergent fiber analysis and national standards “GB/T 20806 − 2006 feed in the determination of acid detergent lignin (ADL)”26 “GB/T 20806 − 2006 feed in the determination of neutral detergent lignin (NDL)”27, as well as the Agricultural Industry standard “NY/T 1459–2007” for determining acid detergent fiber (ADF)28. The mass fractions were calculated as the average of three replicate samples for each diameter class. Holocellulose content and the lignin-to-cellulose ratio were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

Result analysis

Mechanical properties of the root system

Roots of H. rhamnoides root across various growth stages consistently demonstrated high tensile resistance. The mean tensile force was 1-year-old > 4-year-old > 10-year-old H. rhamnoides root. As root diameter increased, the divergence between fitted curves for different age cohorts widened (Fig. 3a). Tensile force exhibited a significant positive power-law relationship with root diameter (Fig. 3a), whereas tensile strength displayed an inverse negative power-law relationship (Fig. 3b). Specifically, mean tensile strength decreased in the order: 1-year-old > 4-year-old > 10-year-old H. rhamnoides. These results confirm a pronounced size effect linking root biomechanical properties to diameter, particularly within the 3–5 mm range. This suggests that finer roots may enhance slope stabilization more effectively than thicker roots, a performance variation primarily attributable to site-specific growing conditions and internal tissue structure29. Additionally, substantial individual variation in tensile strength occurred even among same-age H. rhamnoides root of comparable diameter, aligning with findings by Leung et al.29 and Liu et al.30.

Deformation characteristics of the root system

Figure 4 displays the stress-strain curves of H. rhamnoides root at different ages. Here, the letter “S” represents H. rhamnoides; the number preceding “S” indicates the age, while the number following it denotes the diameter class.

Each stress-strain curve obtained from the tensile tests of H. rhamnoides root exhibited distinct characteristics. For comparison, the ultimate stresses of H. rhamnoides root within the 1–5 diameter class were compared with the average ultimate stresses for that class31, selecting the closest curve as the representative curve for that diameter class32. Figure4 reveals that the ultimate stresses of H. rhamnoides root across different ages and diameter classes showed a negative correlation with root diameter. Specifically, in Fig. 4(a), the ultimate stress for 1-year-old H. rhamnoides decreased from 65.5 MPa in diameter grade 1 to 23.0 MPa in diameter grade 5; in Fig. 4(b), the 4-year-old H. rhamnoides root decreased from 56.5 MPa in diameter grade 1 to 17.2 MPa in diameter grade 5; and in Fig. 4(c), the 10-year-old H. rhamnoides root decreased from 44.9 MPa in diameter grade 1 to 13.1 MPa in diameter grade 5. However, strain was found to be independent of root diameter. The stress-strain curves indicated that all root diameters initially underwent elastic deformation, transitioning to plastic deformation as stress increased, demonstrating significant elastic-plastic characteristics. Differences among the curves for various root diameters indicated that smaller diameters exhibited steeper slopes, requiring greater stress per unit strain.

Characterization of the distribution of the content of major chemical components in the root system

Table 2 presents the contents of the main chemical components of the H. rhamnoides root system across different diameter classes and ages.

As shown in Table 2, lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, holocellulose and the content ratio of lignin to cellulose ranged from 23.85% to 27.58%, 12.32% to 38.21%, 8.60% to 9.78%, 21.19% to 46.81%, and 0.65 to 2.16, respectively. The sum of cellulose, lignin and hemicellulose contents of roots at different ages was as follows: 1-year-old (62.36%) > 4-year-old (53.90%) > 10-year-old H. rhamnoides (53.11%). While these differences were relatively small, significant variations in root chemical constituents were observed among different ages of H. rhamnoides at different diameter levels. Mean lignin and hemicellulose contents decreased with increasing root diameter, with significant differences between the diameter classes of 1-year-old and 10-year-old H. rhamnoides, as well as significant differences in mean hemicellulose content among the diameter classes of 4-year-old H. rhamnoides. The correlations between the contents of other chemical components were not significant.

Analysis of the effect of chemical composition structure on mechanical properties

The spatial structures and chemical formulas of the root chemical constituents are shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 5(a) shows that lignin is a complex reticulated phenolic polymer, primarily composed of phenylpropane units33. It exhibits considerable strength; however, the π-π conjugation of the phenolic polymer’s benzene rings can enhance the overall brittleness of the polymer as its molecular weight increases. Fig. 5(b) depicts cellulose as a linear microfibrillar polymer mesh made up of D-glucose (individual rings)34.Its strong, boat-structured six-membered rings and inter-ring ether bonds35. effectively enhance the stretching and rotation of chemical bonds. Thus, cellulose and lignin provide strength and toughness to the root system. However, the effect of lignin on root tensile strength is weaker than that of cellulose. 1-year-old H. rhamnoides exhibited the highest cellulose content (26.68 ± 2.77%) and, correspondingly, the optimal tensile strength and tensile modulus among all age groups (Tables 1 and 2). Its high-cellulose microfibril structure (Fig. 5b) enhances toughness through ether bonds, while the brittle effect of lignin (26.81 ± 0.45%; Fig. 5a) is counterbalanced by cellulose dominance, resulting in superior tensile performance. In contrast, 10-year-old H. rhamnoides showed significantly reduced cellulose content (19.62 ± 5.01%), with both tensile force and tensile strength lower than those of 1-year-old H. rhamnoides (Table 1). Although lignin content (26.64 ± 0.55%) did not differ significantly from that of 1-year-old H. rhamnoides root, the decline in cellulose weakened the cell wall structure, leading to degraded mechanical properties.The content ratio of lignin to cellulose of 1-year-old H.rhamnoides (0.87–1.18) was significantly lower than that of 10-year-old H.rhamnoides (1.25–1.85), indicating that a lower the content ratio of lignin to cellulose better balances strength and toughness (Table 2). This demonstrates cellulose’s advantage in resisting tensile damage, which is in agreement with the results of the studies of Zhang et al.35 and Commandeur et al.36 Fig. 5(c) shows that hemicellulose, characterized by low polymerization, instability and small molecular weight in an amorphous state37, has certain adhesive properties. The average hemicellulose content in roots of different-aged H.rhamnoides (8.55%−10.08%) was relatively low, with insignificant differences, and its amorphous structure Fig. 5(c) had a weaker impact on mechanical properties.

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients between the parameters, revealing that the tensile strength of H. rhamnoides at different ages is significantly negatively correlated with lignin content and highly positively correlated with root diameter. Conversely, tensile strength shows a significant positive correlation with lignin content and a highly significant negative correlation with root diameter. The relationship between the tensile properties of H. rhamnoides and the components of the root system varies significantly with age, indicating that a single component cannot fully account for the relationshipbetween the mechanical properties and diameter of the root system.

Research has revealed a significant negative correlation between tensile strength and lignin content. This primarily stems from lignin’s brittle nature and its antagonistic interaction with cellulose. The reticular structure formed by phenylpropane units in lignin molecules enhances rigidity through π-π conjugation, yet its high molecular weight simultaneously diminishes the root system’s capacity for energy dissipation during plastic deformation. Furthermore, elevated lignin-to-cellulose ratios constrain cellulose’s contribution to toughness. Tensile strength exhibited a power-law decrease with increasing root diameter (Fig. 3b), with fine roots demonstrating superior tensile performance due to their higher cellulose content and more homogeneous cortex tissue structure. Overall, one-year-old H. rhamnoides root exhibited optimal mechanical properties, significantly outperforming roots from other growth stages.

PLSR-SVM based coupled modeling approach

Partial least squares regression (PLSR)

PLSR is an integrated, all-in-one multiple regression approach37, which utilizes decision variables to mitigate the effects of multiple covariates in the input factors. It efficiently extracts the most informative features to build model Eq38.

Set\({e_{0i}}\)and\({F_0}\)as the normalized vectors of xi, y respectively.Within \({E_0}={\left( {{e_{01}},{e_{02}}, \cdot \cdot \cdot ,{e_{0p}}} \right)^T}\), set \({t_1}\)as the first component of\({E_0}\), \({t_1}={E_0}{w_1}\), and set\({a_1}\)as the first component of\({F_0}\), \({a_1}={F_0}{c_1}\)。.

In PLSR regression, the covariance between component\({t_1}\)and component\({a_1}\)is required to be maximized.

To solve the following optimization problem:

The first component can be obtained applying the Lagrange multiplier method to Eq. (4).

\({E_0}\) and \({F_0}\) are regressed on components \({t_1}\)and \({a_1}\), respectively:

Among them, \({p_1}=E_{0}^{T}{t_1}/{\left\| {{t_1}} \right\|^2}\), \({r_1}=F_{0}^{T}{a_1}/{\left\| {{a_1}} \right\|^2}\). Matrices \({E_1}\) and \({F_1}\) are the residuals from the first regression.

By repeating Eq. (4) to (6) using the residual matrix, k component tk can be derived. The number of components is determined using the principle of cross-validation.

Support vector machine (SVM) modeling

SVM, based on statistical learning theory, aims to minimize structural risk39 to ensure the minimum classification error rate40.The SVM model identifies a categorical hyperplane\(t={w^T}x+b\) and formulates a quadratic programming.

The classification problem can be framed as the following quadratic programming:

By employing the Lagrange multiplier method, Eq. (8) can be transformed into:

,

By defining the kernel function \(K\left( {{x_k},{x_l}} \right)=\left\langle {\varphi \left( {{x_k}} \right),\varphi \left( {{x_l}} \right)} \right\rangle\) instead of \(\left\langle {{x_k},{x_l}} \right\rangle\), Eq. (9) is transformed into a planning problem:\(\hbox{max} \left( { - \frac{1}{2}\sum\limits_{k} {\sum\limits_{t} {{a_k}{a_l}{y_k}{y_l}K\left\langle {{x_k},{x_l}} \right\rangle +\mu \sum\limits_{k} {{a_k}} } } } \right)s.t.\)

Eq.༈10༉addresses the nonlinear classification problem.

Coupled modeling of PLSR and SVM

The coupling of PLSR with SVM has been successfully applied in various fields, including water quality prediction41, air quality prediction42 and dam displacement monitoring43. Given that both PLSR and SVM models exhibit significant prediction errors37,38 due to their inherent nonlinearity36 and the presence of multiple input variables21, a coupled model is constructed to leverage the strengths of both approaches. The flow of PLSR-SVM coupled model analysis is shown in Fig. 6.

PLSR-SVM modeling of tensile Property-Chemical composition linkage

Parameter statistics

Based on the single-root tensile test and chemical composition test data of H. rhamnoides root system, t1 lignin, t2 cellulose, t3 hemicellulose, t4 holocellulose, t5 lignin-to-cellulose ratio and t6 root diameter, a total of six parameters. The dependent variables included y1 tensile force and y2 tensile strength. After removing data that affected modeling variability, 72 sets of representative measurements were chosen as the final sample, with descriptive statistics for the various variables in the H. rhamnoides sample presented in Table 4.

Parameter correlation analysis

From Table 3 in Sect. 3.3, it is evident that the correlation among the six parameters is significant, and multicollinearity among independent variables can lead to instability in the prediction model42, which is very detrimental to modeling analysis43. Traditional linkage methods and data-driven BP models often fail to address the effects of multiple covariates among input factors. While PCA, stepwise regression (SR) and PLSR can help mitigate this issue, PCA extractsprincipal components and contribution rates but neglects the correlation between these components and the dependent variable, resulting in the loss of key information and decreased model prediction accuracy. SR removes highly correlated variables, which may reduce the training data’s plausibility, leading to less effective predictions. Therefore, employing the PLSR coupling method is essential for rationally extracting the explanatory variable characteristics of principal factors.

PLSR-SVM prediction model and effect analysis

Regression using PLSR reveals the percentage of variance change with increasing number of principal components, as shown in Fig. 7.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, PLSR can achieve the lowest percentage of variance by extracting just three principal components, t1, t2, t3 expressions:

The principal components t1, t2, t3 serve as the input layer of SVM, reducing the original six dimensions to three. The output layer contains only two nodes, effectively lowering the dimensionality of the SVM and simplifying the model structure.

To further validate the fitting accuracy of the root tensile mechanics prediction model developed using the PLSR-SVM coupling method, we also established root tensile mechanics prediction models using BP, PCA, PLSR and SVM prediction models were also established based on the above 72 sets of data. Comparison plots of the measured values against the PLSR-SVM coupled predictions, along with the fitting accuracy of the various prediction models, are presented in Fig. 8.The fitting accuracy of different prediction models for tensile force (N) and tensile strength (MPa) is compared in Tables 5 and 6, with model performance ranked according to maximum error.

As shown in Fig. 8; Tables 5 and 6, the measured and predicted values of tensile force and tensile strength for the H. rhamnoides root system across the 72 sample sets are closely aligned. The maximum errors of tensile force and tensile strength were 5.61 N and 3.01 MPa, respectively. The average errors were 1.60 N and 0.41 MPa, with standard errors of 2.13% and 0.82%, and the average relative errors were 3.21% and 2.96%. Overall, the model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting the tensile strength of the root system.

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, which links tensile properties to the chemical composition of H. rhamnoides root, exhibits the smallest error index and outperforms the other four prediction models in terms of fitting accuracy. In conclusion, the PLSR-SVM prediction model for the tensile properties-chemical composition linkage of H. rhamnoides root is reasonable and effective.

Discussion

The study investigated the relationship between the tensile properties of H. rhamnoides root systems and factors such as age and chemical composition. Results indicate that both tensile strength and tensile modulus of root systems exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing plant age (Fig. 3). This pattern aligns with Hou’s findings on the tensile properties of alfalfa fibrous roots across different age stages44. Furthermore, the tensile force and tensile strength of H. rhamnoides root at various ages exhibited a power-law relationship with root diameter, consistent with Genet et al.‘s mechanical studies on three coniferous and two broadleaf tree species12. More notably, root diameter at different ages exhibited a negative correlation with ultimate stress, independent of strain, aligning with Zhang et al.‘s findings on the relationship between root mechanical properties and size45.

When investigating the relationship between chemical constituents in root systems and tensile strength, it was observed that higher lignin content often correlates with lower tensile strength. This finding aligns with the conclusion drawn by Zhang et al.14 regarding a significant negative correlation between lignin content and tensile strength in Pinus tabulaeformis roots. However, this contrasts with the cellulose-dominant tensile performance perspective proposed by Yun et al.46. This discrepancy may stem from the combined influence of plant species, chemical composition levels, spatial arrangement structures, and other substances, necessitating deeper analysis incorporating diverse plant types and primary constituents47,48. Concurrently, it underscores that relying solely on individual chemical components to explain the dimensional relationship between root diameter and tensile mechanical properties proves insufficient49.

This study primarily investigates the typical plant H. rhamnoides within tailings dam remediation zones, proposing a PLSR-SVM predictive model linking tensile properties to chemical composition. Although demonstrating high predictive accuracy, the model does not comprehensively cover the region’s diverse plant communities, thereby limiting its practical engineering guidance due to plant type constraints. Subsequent research should expand sample diversity by selecting representative plants of different types (shrubs, herbaceous species, etc.) and root morphology (taproots, fibrous roots, reticulate roots, etc.) for comparative tensile mechanical studies. This should be combined with advanced characterisation techniques such as CT scanning to elucidate macro-micro mechanisms linking plant tensile performance, chemical composition, and spatial structure. Integrating multi-source data (soil parameters, topography/hydrology, remote sensing imagery) to construct intelligent multi-objective optimisation models will enhance predictive accuracy and generalisation capabilities. This approach enables dynamic assessment of tailings slope stability and precise selection of restoration vegetation, providing scientific foundations for ecological rehabilitation in mining areas.

Conclusion

Based on the chemical composition of H. rhamnoides root, a plant for ecological restoration of mines, we analyzed the tensile properties in relation to the distribution characteristics and chemical structure of the chemical components at different ages and diameters. Using the PLSR-SVM model, we drew the following conclusions:

(1) The average tensile strength of H. rhamnoides is ranked as 1-year-old > 4-year-old > 10-year-old.The tensile force increases as a power function with root diameter, while tensile strength decreases as a power function with age. Significant elastic-plastic characteristics were observed in the stress-strain curves, and the root diameter was negatively correlated with the maximum stress and independent of the strain.

(2) The sum of cellulose, lignin and hemicellulose contents of roots at different ages were as follows: 1-year-old (62.36%) > 4-year-old (53.90%) > 10-year-old H. rhamnoides (53.11%). The average lignin and hemicellulose content decreased with increasing root diameter, with significant differences between the 1-year-old and 10-year-old H. rhamnoides diameter classes. Additionally, there were significant differences in mean hemicellulose content among the 4-year-old diameter classes. While significant variations in chemical content were found among different ages and diameter classes of H. rhamnoides root, the overall correlation was not significant.

(3) The tensile strength of H. rhamnoides root system at different ages was significantly negatively correlated with lignin content and significantly positively correlated with root diameter. Conversely, tensile strength was significantly positively correlated with lignin content and highly significantly negatively correlated with root diameter. The correlation between tensile properties at different ages and root components varied, suggesting that single chemical components could not fully explain their interdependence.

(4) The PLSR-SVM prediction model effectively addressed the issue of multiple covariances among independent variables by extracting three strong principal components as the input space for SVM, thus reducing dimensionality and simplifying the model structure. The maximum errors for tensile force and tensile strength are 5.61 N and 3.01 MPa, the average errors are 1.60 N and 0.41 MPa, the standard errors are 2.13% and 0.82%. The average relative errors were 3.21% and 2.96%, demonstrating high prediction accuracy that exceeds that of the models developed using BP, PCA, PLSR and SVM.

Data availability

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhi, H. et al. Research on shear characteristics and influencing factors of Hippophae rhamnoides root-soil composites [J]. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 32, 184–191 (2025).

Jing, H. W. et al. The application and prospect of clonal plant hzppophae spp. In the management of ecological environment [J]. Shaanxi For. Sci. Technol. 34, 35–38 (2006).

Shi, C. H. et al. Research progress and engineering practice on comprehensive utilization of tailings [J]. China Min. Magazine. 33, 107–114 (2024).

Zhang, Q. Y., Tang, L. X. & Pan, L. Characterization of tensile strength based on chemical composition of root system. J. Nanjing Forestry Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 44, 186–192 (2020).

Su, X. M., Liu, J. M. & Zhou, Z. Z. Tensile properties of different plant root systems in loess hilly areas. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 26, 259–264 (2019).

Ji, J., Kokutse, N. & Ucnet, M. Effect of Spatial variation of tree root characteristics on slope stability;A case study on black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)and arborvitae (Platycladus orientalis)stands on the loess Platcau. China Catena. 92, 139–154 (2012).

Zhou, P., Wen, A. B. & Yan, D. C. Root distribution and tensile resistance characteristics of herbaceous ridge plants on purple soil slopes in the three Gorges reservoir area. Soil. Water Conserv. Bull. 37, 1–6 (2017).

Zuo, Z. Y. & Rentuya, G. R. A comparative study of root tensile properties of three native plants in central and Western inner Mongolia. Soil. Water Conserv. Bull. 35, 52–57 (2015).

Vergani, C., Chiaradia, E. A. & Bischetti, G. B. Variability in the tensile resistance of roots in alpine forest tree specics. Ecol. Eng. 46, 43–56 (2012).

Huang, Y. H., Li, S. S. & Yue, H. Root tensile properties of four herbaceous plants in the avalanche zone and their relationship with chemical composition. Subtropical Soil. Water Conserv. 33, 9–15 (2021).

Hu, J. H., Liu, J. & Li, X. S. Tensile properties of root system of Artemisia Nigra and its correlation with chemical composition. Soil. Water Conserv. Bull. 40, 87–93 (2020).

Genet, M., Stokes, A. & Salin, F. The influence of cellulose content on tensile strength in tree roots. Plant. Soil. 278, 1–9 (2005).

Soippa, G. S., Michele, M. D. & Iorio, A. D. The response of spartium junceum roots to slope: anchorage and gene factors. Ann. Botany. 97, 857–866 (2006).

Zhang, C. B., Chen, L. H. & Jiang, J. Why fine tree roots are stronger than thicker roots: the role of cellulose and lignin in relation to slope stability. Gmorphology 206, 196–202 (2014).

Wu, Q. & Fu, Y. L. Support vector machine. J. Xi’an Univ. Posts Telecommunications. 25, 16–21 (2020).

Hu, P., Wen, Z. & Hu, X. L. Inversion of landslide permeability coefficient based on genetic algorithm and support vector machine. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 48, 160–168 (2021).

Wan, C. X. & Sun, M. Prediction model of mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete based on BP neural network. Sci. Technol. Bull. 37, 90–93 (2021).

Ma, F. Y. & Li, X. X. Landslide displacement prediction model based on improved sparrow search algorithm-coupled kernel limit learning machine algorithm. Sci. Technol. Eng. 22, 1786–1793 (2022).

Mao, K. Z. et al. Source apportionment and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments of Dongping lake based on PCA-PMF model. Sci. Rep. 15, 32026 (2025).

Wei, Q., Jin, L., Chen, W. & Hao, G. Pollution characteristics and source analysis of heavy metals in sediment of Panlong river. Shandong Agricultural Sci. 52, 8 (2020).

Gong, B. Study of PLSR-BP model for stability assessment of loess slope based on particle swarm optimization.[J]. Scientific reports. 11(1), 17888–17888 (2021).

Yang, H., Yue, J. P. & Zhou, Q. K. Combined SVM and Arima model for dam deformation prediction. Surv. Bull. 4, 74–78 (2021).

Delory, B. M., Weidlich, E. W. A., Van, D. R., Pagès, L. & Temperton, V. M. Measuring Plant Root Traits Under Controlled and Field Conditions: Step-by-Step Procedures.[J]. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 1761 (2018).

Yang, Q. C. et al. Study on the cohesive shear characteristics and intrinsic modelling of the root-tailing soil interface of amorpha fruticosa[J]. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 11800 (2022).

Wang, G. H. et al. Content and specification of the research and compilation of Chinese vegetation Journal[J]. J. Plant. Ecol. 44 (02), 128–178 (2020).

GB/T 20805-2006 Determination of acid detergent lignin in feedstuffs [S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2006.

NY/T 1459–2007. Determination of Acid Detergent Fiber in feedstuffs [S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2007.

GB/T 20806 – 2006 Determination of Neutral Detergent Fiber in feedstuffs [S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2006.

Leung, T. Y., Yan, W. M. & Hau, C. H. Root systems of native shrubs and trees in Hongkong and their effects on enhancing slope stability. Catena 125, 102–110 (2015).

Liu, Y. Q., Rele, G. & Ruhan, A. Comparison of tensile resistance characteristics of single roots of five plant species in two growth periods. J. Inner Mongolia Agricultural Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 38, 25–30 (2017).

Qiao, N., Yu, Q. Q. & Lu, H. J. Mechanical effects of plant slope protection in cold and arid environments and the chemical composition response of root systems. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 9, 108–113 (2012).

Bai, L. Y., Liu, J. & Hu, J. H. Study on the mechanical properties of taproot of purple locust (Sophora japonica). Arid Zone Res. 38, 1111–1119 (2021).

Zhang, S. Y. Study on the Effect of Chemical Composition on the Mechanical Properties of Wood Cell Wall (China Academy of Forestry Science, 2011).

Zhang, Q. Y., Tang, L. X. & Pan, L. Study on mechanical properties of shrub root system and applicability of Wu model in Kras. J. Yangtze Acad. Sci. 37, 53–58 (2020).

Zhang, Q. Y., Tang, L. X. & Liao, H. G. Effect of microstructure of root cross section on tensile properties of indigofera multiflora. Plant Ecol. 43, 709–717 (2019).

Commandeur, P. R. & Pyles, M. R. Modulus of elasticity and tensile strength of Douglasfir roots. Can. J. For. Res. 21, 48–52 (1991).

Shi, X. Z., Wu, Y. M. & Tang, L. Z. Application of partial least squares regression neural network model in blast vibration peak velocity prediction. Vib. Shock. 32, 45–49 (2013).

Tanveer, M., Rajani, T. & Rastogi, R. Comprehensive review on twin support vector machines. Ann. Oper. Res. 1, 1–46 (2022).

Tang, R. H. & Luo, W. X. Parameter inversion of soft soil roadbeds based on the optimal support vector machine with the universal gravity search algorithm. J. Railway Sci. Eng. 19, 1568–1576 (2022).

Yu, Q. B., Li, Y. & Bai, Y. Prediction of support vector machine PM (2.5) based on cluster analysis and least squares. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 157–164 (2017).

Zhang, S., Shi, W. R. & Shi, X. Water quality prediction based on partial least squares regression and SVM. Comput. Eng. Appl. 51, 249–254 (2015).

Xu, H. L., Wang, J. L. & Jing, K. Combined model of pls-svm dam displacement monitoring based on wavelet de-noising. Water Power Energy Sci. 28, 81–82 (2010).

Kulkami, S. G. & Chaudhary, Haudhary, Nandi, Andi, S. Modeling and monitoring of batch processes using principal component analysis (PCA) assisted generalized regression neural networks (GRNN). Wbiochemical Eng. J. 18, 193–210 (2004).

Hou, S. Study on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Herbaceous Root Composite Soil and Stability of Shallow Loess Slope [D] (Chang’an University, 2020).

Zhang, Q. Y. et al. Tensile mechanical properties of roots based on chemical composition [J]. J. Nanjing Forestry Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 44, 186–192 (2020).

Yun, C. et al. Root tensile strength of terrace hedgerow plants in the karst trough valleys of SW china: relation with root morphology and fiber content[J]. International soil and water conservation research. 10, 677–686 (2022).

Hu, J. H. et al. Relationship between root tensile properties and its responses to their chemical contents of Artenusza Orcloszca species [J]. Bulletin of soil and water conservation. 40(06), 87–93 (2020).

Baets, D. S. et al. Root tensile strength and root distribution of typical mediterranean plant species and their contribution to soil shear strength[J]. Plant. Soil. 305, 207–226 (2008).

Lu, C. H. & Chen, L. H. Relationship between root tensile mechanical properties and its main chemical components of tipical tree species in North China[J]. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. (Transactions CSAE). 29, 69–78 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Our research was supported by the Project of Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province, China (No. 20180550192); the Liaoning Bai Qian Wan Talents Program, China (No. [2015]33); the Project of Science and Technology of Liaoning Province, China (No. 2019JH8/10300107 and No. 2020JH2/10300100); the Central Guide to Local Science and Technology Development Project of Liaoning Province, China (2021JH6/10500015); the Science and Technology Development Plan of Weifang, China (No. 2023GX071); Department of Transportation Science and Technology Program Project of Shandong Province, China (No. 2024B54).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Y. and Z.H. conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; W.C. and Z.H. processed the data and drafted the manuscript; X.W. and Q.Y. collected experimental samples and the data; D.T. identified experimental samples; X.C. and D.Y. explained and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Q., Hao, Z., Cao, X. et al. Study on tensile properties of Hippophae rhamnoides roots and prediction model of chemical composition in tailing areas. Sci Rep 15, 40150 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23916-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23916-w