Abstract

In the paper the mechanical behavior under low (0.5 s⁻¹) and high-strain rate (50 s⁻¹) of four human cervical spine ligaments, anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), ligamentum flava (LF), and capsular ligament (CL), harvested from elderly donors (70–90 years) is investigated. Results highlight that the PLL, LF, and CL exhibit statistically significant increases in stiffness and elastic modulus under high-strain loading. An increase in the failure force was observed only for the PLL and LF at 50 s⁻¹. Meta-regression analyses revealed that age exerts a negative influence on certain mechanical parameters, emphasizing the need for age-matched biomechanical data in both clinical and computational studies. A visco-hyperelastic constitutive model was fitted to the experimental stress-stretch curves, capturing both low-strain and high-strain rate responses with high goodness-of-fit metrics. Presented results advance understanding of ligament mechanics in older populations and offer valuable data for improving mathematical models aimed at injury prediction, particularly for high-impact events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

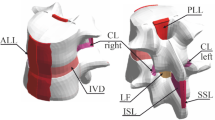

Cervical spine ligaments, including the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), the ligamentum flava (LF), and the capsular ligament (CL), are critical for maintaining the structural integrity and functionality of the neck1. They can be subjected to complex mechanical forces with strain-rates varying from relatively low, typical for usual daily activities, to high, occurring in sudden, high-velocity events like, e.g., sport-related impacts, falls, or car crash accidents. Sudden and unexpected spine movements that exceed the physiological range can cause ligament damage2. Thus, accurate identification of specific stress and strain thresholds that lead to ligament rupture is crucial for the effective design of spinal protection devices and safety features in vehicles, such as seat belts and headrests3,4.

To date, the mechanical response of human cervical spine ligaments has been studied under low1,5,6,7 or high-strain rate8,9. However, the analysis of the influence of strain rate on their properties is limited10,11,12. In10 it was considered for a younger population only. While in11 relatively low-strain rates were investigated, and in12 only two ligaments from an unspecified population were investigated. Consequently, despite their increased susceptibility to injury, older individuals have received comparatively less attention in the investigation of viscous properties. This emphasizes the need to extend the study of both the strain-rate effect and ageing on ligament biomechanical properties. The ageing population presents unique challenges due to age-related changes of biomechanical properties, such as reduced elasticity, altered collagen composition, and decreased cross-sectional areas, which can affect injury patterns and recovery processes13. Understanding how the mechanical behavior of cervical spine ligaments changes with age is crucial for developing more effective injury prevention and treatment strategies for the elderly population, who are at a higher risk of sustaining cervical spine injuries due to factors like decreased muscle strength and balance.

Nowadays, the development of these strategies can be successfully supported by numerical simulations. Indispensable tools in this field are the human body models (HBMs), such as the Total Human Model for Safety (THUMS) and the VIVA+4,14,15,16. They aim to simulate the response of the human body under various loading conditions and are often used in analyses of advanced safety systems, like airbags or road safety barriers, etc6. These models provide information about the complex mechanisms underlying injury without the ethical and practical constraints associated with cadaveric testing17. However, the accuracy of HBMs is limited by the biomechanical data they incorporate. These limitations are related especially to the geometry and material parameters of the tissues and organs. Most existing HBMs are based on data derived from younger cadavers and simplifying assumptions, which do not adequately capture the nuanced biomechanical properties of tissues in older populations18. Incorporating accurate, age-specific biomechanical data into HBMs is, therefore, crucial for enhancing their predictive accuracy and ensuring their relevance across diverse anthropometric groups. Thus, age-related alterations in ligament structure and function warrant further investigation. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, previous studies have not comprehensively described the strain rate effect on the mechanics of cervical ligaments and their properties under high-strain rates typical of real-world injuries5,6,19 in the elderly population.

Taking the above into account, this work presents an investigation of the low-strain and high-strain rate tensile response characteristics of cervical spine ligaments from older adult cadavers20. The study involves experimental tensile testing of ligament samples, followed by developing a potential constitutive model that accurately matches the observed experimental data. In the authors’ opinion, the anticipated outcomes of the work can serve as a valuable support across a range of practical fields, such as e.g., the design of therapeutic and injury prevention techniques for the elderly population and improvements of vertebral column models in in silico studies, including those with HBMs14,15,21,22.

Materials and methods

Gratitude to the body donors and their families is conveyed in the Acknowledgements in accordance with the guidelines of23. All cadavers analyzed in this work were acquired through a body donation program, following consent for use in educational and scientific activities. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IRB reference: Ordinance No. 26/2016 of the Rector of the Medical University of Gdańsk, dated June 6, 2016, concerning the “Program of Conscious Donation of Corpses”). A total of seven human cervical spines (mean donor age 78 years within a range 70–90) were obtained. The donor group comprised two males and five females, with an average weight of 78 kg (range 60–90 kg) and an average height of 172 cm (range 150–190 cm). Within 24–48 h postmortem, specimens of 15 ALL, 17 PLL, 13 LF, and 29 CL were isolated. Only those ligaments without any detectable pre-existing bone or soft-tissue pathology were included. Relevant anthropometric data, specifically age, gender, weight, height, and autopsy details, were collected and recorded for each donor in Table 1.

Specimens

Preparation

Each spine was harvested through a posterior approach. Two sagittal skin incisions were initially made, positioned 30–40 mm lateral to the posterior midline on each side of the spine. This incision extended from the occipital bone to the sacrum. The skin flap, along with underlying subcutaneous tissue, was dissected and excised. Subsequently, the dorsal muscles were detached from their cranial attachments. The muscles spanning the spinous processes, including the dorsal extensor muscles, were systematically dissected and removed. Next, the atlantooccipital and sacroiliac joints were resected. The ribs were transected approximately 10 mm lateral to the transverse processes, and the sacrum was horizontally sectioned at the S2/S3 level. The quadratus lumborum muscles were also debrided. Following these procedures, the entire spine was extracted and examined from an anterior view, with particular attention to the diaphragm and the psoas major muscles.

The spine was then lavaged three times with chilled saline (0.9% NaCl) at approximately 6 °C, each lavage lasting 15 min. The vertebral column was segmented after removing the short muscles and excising remnants of ribs at the costovertebral joints. The isolated segment of the entire cervical spine (C2-T1, with Ci and Ti standing for the i-th vertebra of the cervical and thoracic spine, respectively) was divided into functional spine units (FSUs). First, the intervertebral discs were cut, then the ligaments were dissected, and the facet joints were excised every other level, resulting in three FSUs named as C2–C3, C4–C5, and C6–C7.

Next, the obtained vertebra-disc-vertebra units were dissected to obtain the desired bone-ligament-bone (BLB) specimens (see Fig. 1). From each segment, the ALL, PLL, LF, and CL (left and right) were collected. The ligaments were then cleaned of fatty tissue. The ALL and PLL were separated from the bisected intervertebral disc. The nucleus pulposus was removed first, after which the annulus fibrosus (AF) was separated from the vertebral bodies along both the superior and inferior cartilaginous endplates (CEP). Final dissection of the AF from the deep layers of the longitudinal ligaments was initiated from the lateral aspects, taking into account morphological differences in fiber structure and orientation between the longitudinal ligaments and the AF. While the AF is characterized by a lamellar architecture with circumferentially arranged fiber bundles, the longitudinal ligaments consist of longitudinally oriented fiber bundles. The ligaments were then cleaned of fatty tissue. Preparation of the vertebral column and ligaments was performed by experienced anatomists using sharp and blunt techniques and a variety of dissection instruments. Each of the obtained samples was wrapped in multiple layers of lignin soaked in isotonic saline solution, then placed in a string bag and frozen at − 20 °C.

Geometry measurements

The boundaries of the ligaments were identified by an anatomy specialist through visual assessment of tissue texture, a tactile evaluation of differences in stiffness, and an analysis of the displacement range during the rotation of bone fragments. The initial length \(\:l\) of the ligament was assumed as the average distance between the bone attachments. To determine this, the boundaries of the ligaments were marked at the edge of the bone using a copying pencil, and the specimens were subjected to an initial preload of approximately 50 g. Next, photographs were taken from both sides of each specimen with the camera mounted on a tripod. The camera was aligned so that its optical axis was as perpendicular as possible to the background reference ruler. These photographic images were then uploaded to a computer-aided design environment (AutoCAD, Autodesk, Inc., USA) for further analysis. The images were scaled to their true size using a ruler with 1 mm divisions. The midlines of the marks were drawn with polylines whose width was set to 0. The boundary of the tested ligament is indicated by the green line in Fig. 2. A vertical array of black lines was drawn at 0.5 mm intervals, and the distance between boundaries was measured along each line. The initial length \(\:l\) was subsequently defined as the mean distance averaged across all such lines with 0.1 mm precision and was used to calculate the specimens’ stretch \(\:\lambda\:\). Following the approach described in reference10, the cross-sectional area \(\:A\) of each sample was estimated using the length-to-area ratio r. The ratios r for all ligaments were determined based on the mean values from the study7. For the LFs, and CLs, the relevant length corresponds directly to the initial length \(\:l\). However, for the ALL and PLL, the relevant length is defined as the distance between the centers of adjacent vertebrae. For these ligaments, the centers of the vertebrae were identified as the midpoint of the distance between the ligament attachments to the vertebrae, and the inter-centroid distance was subsequently measured within the graphical software7,8,10.

Mounting to the testing machine

The samples were removed from the freezer and placed in saline for approximately one hour. To mount the BLB samples in the testing machine, the specimens were placed into 3D-printed PLA cups24 and potted using resin (Technovit 3040, Kulzer GmbH) mixed with sand (CEN EN 196-1 standard)25. To enhance friction between the bone and the resin and to mitigate damage associated with boundary effects, the BLB complexes were reinforced as shown in Fig. 3. For ALL and PLL, sandpaper was applied to improve grip. Additionally, two cable ties were used to compress the vertebral body longitudinally, and circumferential wire wrapping was used for further stabilization (see Fig. 3A and B). For the LF, a centrally positioned steel screw was inserted into the middle of the bone (Fig. 3C), along with longitudinal reinforcement using cable ties. The CL BLB complexes were reinforced both circumferentially and longitudinally using wire ties (see Fig. 3D).

The casting of the reinforced samples was conducted as follows: for the ALL and the PLL samples, the cups were filled up to the level of the ligament attachment. For the LF, the cups were filled to completely cover the centrally positioned screw. Similarly, for the CL, the resin mixture was added to cover all applied reinforcement. During the curing process, the samples were wrapped in saline-soaked lignin to maintain moisture. After 15 min, the opposite side of each sample was mounted following the same procedure. Once both sides were prepared, the samples were wrapped in several layers of plastic stretch film and stored in a refrigerator at approximately 5 °C for 24 h to ensure complete curing.

Tensile tests

Low-strain rate

Before testing, the samples were removed from the refrigerator and immersed in physiological saline solution. Then samples were mounted in the tensile testing machine and subjected to an initial preload of 5 N tensile force, applied at a strain rate of 0.5 s⁻¹10. Subsequently, the samples were allowed to relax for 60 s26. Then, preconditioning was performed, which involved 60 cycles of 10% strain (\(\:0.1l\)) at a frequency of 1 Hz, followed by a 60 s recovery period. During the tensile testing phase, the samples were continuously strained at a rate of 0.5 s⁻¹ until complete rupture. All tests were conducted in an environmental chamber (see Fig. 4B) maintained at a constant temperature of 36.6 °C and a minimum relative humidity of 95%.

The tests were carried out using a custom-designed machine (Patent application: P.443948) (see Fig. 4A). This device features an AC stepper motor (Leadshine ELM-0400LH60F-SS-400 W) controlled by a servo controller (Leadshine ELP-RS400Z, 0.001 mm accuracy), which is connected to a linear module (YR-HGWS60K SFU1605). Force data were acquired from three bottom-mounted load cells (Utilcell M140, up to 1500 N). The displacement of the load cell (bracket) was recorded using a servo controller and a universal amplifier HBM QuantumX MX840A (Hottinger Baldwin Messtechnik, Germany) with Catman Data Acquisition Software.

High-strain rate

The high-strain rate tests were conducted using a modified version of the custom-designed tensile testing machine described in the previous section (see Fig. 5). The top-mounted load cell (bracket) was replaced with a rigid bracket. A steel guide with an absorber was installed through the hole in the rigid bracket. Preconditioning and data acquisition were carried out in the same way as described in the low-strain rate test section. To avoid eccentric position of the sample, a 3D-printed stabilizer with leveling screws was used. During the high-strain rate tensile test, the machine accelerated the rigid bracket to a strain rate of 50 s⁻¹ and maintained this value until the sample completely ruptured. The test configuration required a modification of the environmental control procedure. Instead of an environmental chamber, the specimens were stored in physiological saline solution at 36.6 °C immediately prior to testing. The entire main test was conducted within 10 min of removing the specimen from the solution.

Force-displacement post-processing

The post-processing steps described below were carried out in a custom Python script. A standardized post-processing procedure was implemented to extract characteristic regions and points from low-strain and high-strain rate ligament tensile tests. The raw force-displacement curves were segmented based on the well-established three-phase response of ligamentous tissue: (1) the toe region (from the initial point to the I transition point), (2) the linear region (between the I and II transition point), and (3) the sub-failure region (spanning from the II transition point to the failure point) (see Fig. 6)11,27. These points (initial, I transition, II transition, and the failure points) were systematically identified using a multi-step computational method, summarized as follows.

The raw data (displacement \(\:\varDelta\:u\) and force \(\:F\)) were smoothed with Savitzky–Golay filters to obtain a stable derivative of the force signal. An onset index of relevant data was established by requiring that both the smoothed derivative and the force exceed specified thresholds for a persistent window of samples. Additional points before the onset index were included in the clipped data to retain enough data for subsequent filtering. Then, the load-displacement curve was trimmed slightly beyond the peak force to ensure that the clipped data included the full ligament test.

Next, the clipped data were processed using a fifth-order, two-pole, Butterworth low-pass filter and an adaptive cutoff frequency selection approach. Cutoff frequencies were determined by integrating the Energy Spectral Density of the force signal until 95% of the energy was captured28. Additionally, a maximum cutoff frequency of 300 Hz was adopted to consider the physiological limitations of wave propagation in soft tissues based on SAEJ211 guidelines29. This hybrid approach suppressed measurement noise, without attenuating the relevant mechanical response. After filtering, indices corresponding to the initial point and failure point were identified in near-zero derivative regions to eliminate redundant data associated with machine stabilisation or late-stage noise.

The linear region for identifying the I and II transition points (see Fig. 6) was found by a binary search that located the largest segment exhibiting a linear fit (adjusted \(\:R^{2}>99.5\%\)) above a threshold. The segments from early toe and later sub-failure regions were excluded by imposing displacement bounds.

Averaging of experimental curves

The displacement increment \(\:\varDelta\:u\) was used to calculate each specimen stretch value with the following formula \(\:\lambda\:=\frac{l+\varDelta\:u}{l}\), where \(\:l\) is sample’s initial length. To obtain the corresponding stress value \(\:P=\frac{F}{A}\) (the engineering stress), force \(\:F\) value was divided by sample’s initial cross-sectional area \(\:A\). Characteristic points (I and II transition points) on the stress-stretch curves were averaged to obtain average ligament curves up to the averaged II transition points. Then, a linear function was fitted between the averaged I and II transition points, whereas the average tissue response between the initial point and the I transition point was captured by an exponential convex function, maintaining C¹ continuity with the linear function and ensuring a non-decreasing trend.

Transversely isotropic visco-hyperelastic constitutive model

The ligament structure is conceptualized as a composite material consisting of a base extracellular matrix strengthened by embedded collagen fibers.

The hyperelastic potential function, \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{i}\text{s}\text{o}}^{\text{e}}\) is split into the matrix \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{e}}\) and fibers \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}^{\text{e}}\) parts1,30:

where \(\:J=det\left(\mathbf{F}\right)\) is the Jacobian of deformation gradient \(\:\mathbf{F}\), variables \(\:\stackrel{-}{{I}_{1}}=\text{t}\text{r}\left(\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}\right)\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{{I}_{4}}={\mathbf{A}}_{0}\hspace{0.17em}:\hspace{0.17em}\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}\) are invariants of right Cauchy-Green tensor \(\:\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}={\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}}^{\text{T}}\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}\), in which \(\:\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}={J}^{-\frac{1}{3}}\mathbf{F}\), and \(\:{\mathbf{A}}_{0}={\mathbf{a}}_{0}\otimes\:{\mathbf{a}}_{0}\) is the fiber direction tensor in initial configuration.

A Neo-Hookean model was used to describe the matrix part \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{e}}\)31 with volumetric term suggested by Martins et al.32, resulting in:

where \(\:{C}_{10}=0.5\mu\:\), \(\:\mu\:\) is a shear modulus in MPa, \(\:{D}_{1}=\frac{2}{K}\) is a compressibility constant in \(\:\text{M}\text{P}{\text{a}}^{-1}\) and \(\:K\) in MPa represents the bulk stiffness33. For incompressible materials, \(\:{D}_{1}\) can be also calculated using:

where v is the Poisson ratio.

The polynomial function capturing the behavior of the fibers is expressed as:

The viscous isochoric component \(\:{{\uppsi\:}}_{\text{i}\text{s}\text{o}}^{\text{v}}\) is associated with both the matrix, and the fibers, characterized by the material constants \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\), respectively. The contributions from these terms are added according to the method proposed by30,34,35:

where \(\:\stackrel{-}{{J}_{2}}=\frac{1}{2}\text{t}\text{r}\left({\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}}}^{2}\right)\hspace{0.17em}\) and \(\:\stackrel{-}{{J}_{5}}={\mathbf{A}}_{0}\hspace{0.17em}:\hspace{0.17em}{\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}}}^{2}\) are viscous invariants of derivative of the right Cauchy-Green tensor \(\:\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}}={\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}}}^{\text{T}}\hspace{0.17em}\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}+{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}}^{\text{T}}\hspace{0.17em}\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{F}}}\). The terms are influenced by the square of \(\:\dot{\stackrel{-}{\mathbf{C}}}\), guaranteeing a dissipation potential that is positive-definite and responds to the magnitude of the strain rate, independent of its direction30,35.

Material parameters identification for uniaxial stress state

For the considered material model, five unique material parameters (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), \(\:{C}_{3}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\)) must be established. In the present study they are identified via curve-fitting procedure by making use of the experimental data from uniaxial tensile tests up to II transition point. Denoting the displacement direction as 1, which is the fibers direction, the uniaxial stress state expressed in terms of engineering stress \(\:{P}_{11}\) yields \(\:{P}_{11}\ge\:0,\:{P}_{22}={P}_{33}=0\). Assuming material incompressibility \(\:\left(\nu\:\approx\:0.5,J\equiv\:1,\:{\lambda\:}_{1}=\lambda\:,{\lambda\:}_{2}={\lambda\:}_{3}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\lambda\:}}\right)\) the invariants defining the energy function read:

The first principal value of the engineering stress \(\:{P}_{11}\), which is used for fitting procedures can be obtained from the following chain rule36:

Finally, using Eq. (9) together with the energy functions Eqs. (2), (4), (6) and Eqs. (7), (8), the expression for \(\:{P}_{11}\) is obtained as follows:

The material constants were determined by fitting the equation (Eq. (10)) through a nonlinear least-squares method (Python’s scipy.optimize library) to the experimental data up to the II transition point stretch value (\(\:{\lambda\:}_{\text{I}\text{I}}\)).

While fitting the (Eq. (10)) to the low-strain-rate data (0.5 s⁻¹) the assumption of negligible viscous effects (\(\:{\eta\:}_{1},\:{\eta\:}_{2}\approx\:0\)) was made, leading to the determination of three unique material constants (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\)). Additionally following constraints were made:

-

1.

Bounds: The shear modulus was assumed to be \(\:\mu\:\in\:[0.2;2.5]\hspace{0.17em}\text{MPa}\), implying \(\:{C}_{10}\in\:[0.1;1.25]\hspace{0.17em}\:\text{MPa}\) consistent with range reported in the literature1,35 and basing on the authors’ experience that lower values than \(\:0.2\hspace{0.17em}\text{MPa}\) of shear modulus may lead to numerical instabilities in FEM simulations,

-

2.

Convexity Condition: \(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\) and \(\:{C}_{3}\) to be positive, ensuring the convexity of the energy functions,

-

3.

Energy Ratio Penalty: a penalty term to enforce \(\:\frac{{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{e}}}{{\text{W}}_{\text{i}\text{s}\text{o}}^{\text{e}}}<0.5\) at the second transition point, to maintain a fiber-dominated response at higher stretches1,27. If this condition was satisfied, the penalty remained zero; otherwise, it was set to a high value (e.g., 100).

For the high-strain (50 s⁻¹) rate data viscous effects were included in the model, resulting in a set of five constants (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), \(\:{C}_{3}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\)). The following assumptions were implemented during the curve‑fitting procedure:

-

1.

Parameter Penalty: A penalty term was introduced to ensure that the mean values of \(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\) remained close to those determined at the low-strain rate (0.5 s⁻¹).

-

2.

Bounds: The minimum and maximum values of \(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\) derived from the low‑strain rate (0.5 s⁻¹) dataset were used as parameter bounds.

-

3.

Convexity Condition: The parameters \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\) were constrained to be positive, thereby maintaining the convexity of the energy functions.

-

4.

Energy Ratio Penalty: Analogous to the low‑strain‑rate fitting, an additional penalty was imposed at the second transition point to enforce \(\:\frac{{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{e}}+{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{v}}}{{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}^{\text{e}}+{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}^{\text{v}}}<0.5\), where.

-

5.

\(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{v}}={\int\:}_{1}^{{\lambda\:}_{\text{I}\text{I}}}{P}_{11,m}^{\text{v}}\hspace{0.17em}\text{d}\lambda\:\) and \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}^{\text{v}}={\int\:}_{1}^{{\lambda\:}_{\text{I}\text{I}}}{P}_{11,f}^{\text{v}}\hspace{0.17em}\text{d}\lambda\:\).

The Adj. R2, normalized root mean square error (NRMSE), and normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) metrics were used to evaluate the agreement between the experimental data and the fitted model.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statsmodels library in the Python environment37. In this analysis, the results of ligament stiffness, elastic modulus, failure force, and failure stress were compared under two loading conditions – low-strain and high-strain rate. For each ligament group, the mean and standard deviation were calculated, providing an initial assessment of the measurement characteristics. To evaluate the significance of differences between the loading conditions, statistical tests were applied: if the data exhibited a normal distribution (as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test), a Welch’s t-test was performed; otherwise, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was employed.

Results

Experimental results and post-processing

The geometric and mechanical properties of four cervical spine ligaments under low‑strain and high‑strain loading conditions are presented in Table 2. The parameters include cross‑sectional area A, initial length l, stiffness (slope in the linear region of the F(\(\:\varDelta\:u\)) curve), and elastic modulus E (slope in the linear region of the \(\:{P}_{11}\left({{\uplambda\:}}_{1}\right)\) curve). Additionally, failure force Ff represents the load at ligament rupture, while failure stress corresponds to the \(\:{P}_{11,f}\) value at failure. Transition points I and II, determined via the procedure outlined in Sect. 2.2.3, are reported in terms of the displacement (\(\:\varDelta\:u\)) and force at each point. The mean length of the cervical spine ligaments ranged from 6.4 mm to 9.9 mm, while the mean failure force Ff ranged from 118.6 N to 247.9 N. Among the ligaments examined, the highest modulus of elasticity was found in the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) (72.81 MPa at high-strain load), while the lowest value was found in the capsular ligament (CL) (8.59 MPa at low-strain load). Sample dimensions and mechanical properties of the ligaments, expressed as medians and quartiles, are provided in the Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of mechanical properties was performed using quasi-static loading conditions as the baseline. Along with the percent change, Table 3 lists the corresponding p-value and the effect size (Cohen’s d or Cliff’s δ in the nonparametric case). In the Table 3, N stands for the number of samples, whereas S denotes the low-strain rate test, and D the high-strain rate test. The percentage change was computed as \(\:\varDelta\:=\frac{\text{(D}-S\text{)}}{S}\times\:100\%.\) Welch’s t-test was applied in all comparisons except for the failure force (Ff) in the CL group, where Mann–Whitney’s U test was chosen due to non‐normal data. A statistically significant effect of strain rate on stiffness and elastic modulus (marked with an asterisk) was identified in the PLL, LF, and CL groups. Specifically, stiffness and elastic modulus in the PLL group rose by 37.03% and 85.68%, respectively; in the LF group, they increased by 78.35% and 75.13%; and in the CL group, both parameters increased by 48.15% and 49.58%, respectively.

Constitutive parameters

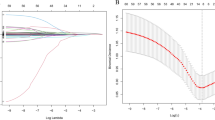

The boxplots of three hyperelastic parameters (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\)) identified from low-strain rate tests (0.5 s⁻¹) are presented in Fig. 7 for each ligament type (ALL, PLL, LF, and CL). Each boxplot shows the inter-quartile range (box), median (horizontal line), and whiskers extending to 1.5 × IQR; outliers are indicated by grey \(\:\times\:\) symbols. The mean value for each parameter appears beneath the corresponding ligament label.

The goodness-of-fit metrics (Adj. R², NRMSE, and NMAE) for the hyperelastic model fitted to experimental data for the low-strain rate tests are presented in Table 4. For all ligaments, the coefficient of determination R² exceeded 0.98, while the normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) and normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) remained low, ranging from approximately 0.02 to 0.03.

The hyperelastic model obtained with the mean values of \(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\) (see Fig. 7) was plotted up to each ligament’s mean II transition stretch value (see Fig. 8). Figure 8 also shows the corresponding experimental data (Exp. Data, grey lines), and averaged experimental data (Avg. Exp. Curve, black line) determined according to the method described in Sect. 2.2.4. The goodness-of-fit statistics (Avg. Exp. Curve vs. Model) are presented in Table 5. The coefficient of determination R² ranged from 0.69 for the capsular ligament (CL) to 0.96 for the ligamentum flavum (LF). The normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) varied between 0.05 and 0.16, while the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) ranged from 0.04 to 0.14.

The boxplots of five parameters (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), \(\:{C}_{3}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\), and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\)) obtained from fitting the high-strain rate (50 s⁻¹) data are presented in Fig. 9, using the same boxplot conventions as described for Fig. 7. The highest median value of parameter \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\) was observed in the LF group, while the highest median value of parameter \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\) was found in the PLL group.

Table 6 presents the mean ± SD of the goodness-of-fit metrics (Adj. R², NRMSE, and NMAE) for the visco-hyperelastic model calibrated to experimental data for the high-strain rate tests. The coefficient of determination R² exceeded 0.96. The normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) varied between 0.02 and 0.04, while the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) ranged from 0.02 to 0.04.

The visco-hyperelastic model was derived from the mean values of \(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), \(\:{C}_{3}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\), and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\), as shown beneath the boxplots in Fig. 9. Figure 10 presents mean-parameters visco-hyperelastic model with the corresponding experimental data (Exp. Data, grey lines), and averaged experimental curve (Avg. Exp. Curve, black line), see Sect. 2.2.4. The goodness-of-fit statistics (Avg. Exp. Curve vs. Model) are summarized in Table 7. The coefficient of determination R² exceeded 0.96. The normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) varied between 0.03 and 0.07, while the normalized mean absolute error (NMAE) ranged from 0.03 to 0.06.

Discussion

Preliminary tests on animal samples revealed a critical issue related to the assembly and positioning of unreinforced BLB complexes in the testing apparatus. Specifically, the samples tended to slip out of the resin-sand mix, undermining the reliability and validity of the experimental data. Furthermore, when the unreinforced BLB complexes were stretched, the ligament attachment often detached, or the bone fractured, rather than experiencing ligament rupture. This failure mode was likely attributed to the inherent structural weakness of the ligament–bone interface or the brittleness of the bone when subjected to tension.

To address these challenges, the BLB complexes were reinforced to prevent undesirable damage such as bone fracture or bone–ligament separation during uniaxial tensile testing2,10. This reinforcement was necessary to ensure both sample integrity and the reliability of the test results10,11. As a result, no premature slippage occurred in any of the reinforced BLB complexes, and ultimate failure consistently occurred within the ligament tissue itself.

It should be acknowledged that the method used to estimate the cross-sectional area of the ligaments is approximate and may not yield fully accurate values of elastic modulus and failure stress. Direct measurement of the cross-sectional area requires destructive procedures, which are not feasible in the present context. In addition, despite cleaning, the specimens often contained surrounding tissues that could not be completely removed. Moreover, the inherently complex geometry of the ligaments makes non-invasive approaches are prone to measurement inaccuracies.

A comparison of ligamentous mechanical properties obtained in the current study with those from prior literature1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 is illustrated in Fig. 11. The failure forces and stiffness values observed in the present study generally fall within the ranges reported in previous research. The observed discrepancies are likely due to differences in strain rate, donor age, sample preparation technique, demographic factors, and testing methodology. It is worth mentioning that despite the use of similar test conditions as the environmental chamber (for low-strain rate) and a standardized preconditioning protocol, the current mechanical properties were lower than those obtained in10. This can be explained by the fact that the average donor age (78 ± 6.34 years) in the present study was significantly higher than in10, where 27–50 years cadavers were studied. Furthermore, in10, the strain rate used in the high-strain rate tests was 3–5 times higher than in the current work. In general, the obtained values of failure forces and stiffness are in good agreement with the mechanical properties reported in studies involving older donors, such as6,11 for low-strain rate testing and9 for the high-strain rate testing. This is particularly evident for the LF ligament, for which the mean failure force in the present study (135.27 ± 54.23 N at 0.5 s⁻¹) is within the range (118.42 ± 27.48 N) obtained in11. Such consistency suggests that the mechanical properties of ligaments from older specimens converge to similar ranges under comparable testing conditions.

Younger donor populations often present ligaments with better-preserved collagen fiber orientations and less degenerative changes, thereby resulting in comparatively higher failure loads and greater stiffness11,38. This difference in tissue properties between younger and older populations underscores the importance of considering donor age and associated tissue quality when interpreting biomechanical data. Extrapolating biomechanical properties derived from younger cadaveric specimens to older populations risks overlooking the complex, age-related deterioration of the ligamentous tissues39,40. In the design of spinal implants, planning surgical stabilization procedures, evaluating dynamic events like sport accidents or car crashes, acknowledging these age-related differences is essential. Degenerative changes in the vertebrae and intervertebral joints may contribute to weakening of the ligament-bone interface, thereby reducing the overall load-bearing capacity and energy absorption potential of the vertebral column41,42,43, increasing the risk of injury and impaired function39,40.

A Weighted Least Squares (WLS) Meta-Regression was performed on data presented in Fig. 11. The effect of age on stiffness and failure force parameters for each ligament type was studied. High-strain and low-strain rates were considered separately. In each case, a negative regression coefficient value was obtained. However, the statistical significance and effectiveness of the regression model of this relationship were demonstrated only for the cases shown in Table 8. For the other cases, the proposed model did not perform well enough, and the p-value was greater than 0.05. The reason could be an insufficient amount of data.

The negative coefficients in Table 8 suggest that specimens harvested from significantly older donors have reduced stiffness if compared to cadaveric specimens from younger donors44,45. Over the human lifespan, the ligamentous tissues, comprising collagen and elastin, undergo progressive modifications at both the micro- and macrostructural levels, which are further intensified in the course of ageing46,47. Cumulative microdamage, such as microscopic tears and disruptions, along with collagen fiber disorganization and the infiltration of fibrotic and sclerotic processes, can render the tissue more fragile.

10 conducted a comprehensive study of the strain rate effect on the mechanical properties of cervical spine ligaments collected from a younger donor population. Their study revealed a significant stiffness dependency on the strain rate of all ligaments except the LF. In contrast, in our study, the LF exhibited the greatest increase in stiffness with the strain rate increase (78%), which was essentially greater than in10 (22%) and lower than in12 (265%). Our result corresponds well to1 under low-strain rate and to9 under high-strain rate, see Fig. 11. The stiffness increase observed for the strain rate of 50 s⁻¹ for the PLL and CL (Table 3) was slightly greater than the increase reported for the medium strain rate (20 s⁻¹) in10 (37% vs. 34% for the PLL and 48% vs. 43% for the CL)10. observed about two times greater strain rate effect for the high-strain rate (150–250 s⁻¹) than for the medium-strain rate. Generally, in the current study, a significant stiffness increase with the strain rate growth was obtained for all ligaments except ALL (Table 3), which exhibited approximately 19% lower stiffness at high-strain rate compared to quasi-static loading (Table 3). A 4% decrease in Young’s modulus, compared to a 19% decrease in stiffness, suggests that this decrease can be partially explained by the shorter length of the ligament samples used in the low-strain rate tests. Moreover, while in other studies1,7,10 the stiffness of the PLL was found to be greater than that of the ALL, in our low-strain rate tests the stiffness of the ALL was 25% greater than that of the PLL (Table 2). This suggests that relatively strong samples were used in the low-strain rate tests, which, combined with the small sample size and high biodiversity of the samples, may have resulted in the observed decrease in stiffness at higher strain rate in the ALL group. Furthermore, whereas in the other ligament groups the force at the second transition point was comparable for both strain rates, in the ALL group a 39% lower force was obtained in the high-strain rate tests compared to the low-strain rate tests (Table 2). The visco-hyperelastic constitutive model (10), which showed very good agreement with the experimental data (Table 7), predicts that the stiffness of the ligament increases during loading. Therefore, the significantly lower force at the second transition point may have reduced the stiffness of the ALL obtained in the high-strain rate tests due to the premature failure of some samples.

In the current study, a statistically insignificant increase in the failure force was observed only for the PLL and LF ligaments at high-strain rate tests (Table 3). Similarly, a smaller strain rate effect on the failure force than on stiffness was observed in10, where a significant increase was reported only for the CL. The greatest effect of strain rate on the failure force was obtained for the PLL (64%) and was greater than that reported for the medium strain rate (20 s⁻¹) in10 (46%). Thi result may be the effect of the relatively low failure load obtained for the PLL in the quasi-static tests compared to that obtained in1. In summary, comparison of our results with the rate dependence of mechanical properties documented by others8,9,10,12 indicates a smaller strain rate effect on the stiffness and failure load in the elderly population.

Direct comparison of the mechanical properties of spinal ligaments obtained at different strain rates is difficult. Therefore, in the current study, the visco-hyperelastic model taking into account the influence of collagen fiber reinforcement was proposed to describe rate-dependent, viscous mechanisms. In this formulation, the viscous component is adapted from approaches developed for collagenous tissues integrating a hyperelastic framework to capture the pronounced nonlinear response of ligament structures30,35. This approach contrasts with simplified linear-elastic models used in some HBMs, which do not account for fibrous tissues anisotropy or viscous effects15. Consistent with the strategy adopted in previous studies on soft tissues35. The material parameters are identified through a two-step curve-fitting process. First, hyperelastic parameters (\(\:{C}_{10}\), \(\:{C}_{2}\), and \(\:{C}_{3}\)) are extracted from quasi-static (0.5 s⁻¹) tests to represent the rate-independent behavior. Then, the viscous parameters (\(\:{\eta\:}_{1}\), and \(\:{\eta\:}_{2}\)) are derived under high-strain-rate conditions (50 s⁻¹), capturing additional time-dependent effects. This division ensures that both the elastic and the viscous contributions are separated and accurately quantified.

The high coefficients of determination (Adj. R²) and the low error metrics (NRMSE, NMAE) reported in Table 4-Table 7 and results illustrated in Fig. 7-Fig. 10 confirm that the present visco-hyperelastic model accurately characterizes the nonlinear and time-dependent behavior of the tested ligaments. The worst goodness-of-fit metrics were obtained for the mean-parameter hyperelastic model for the CL and ALL (Table 5), which may overestimate the static ligament response at stretches greater than 1.2 and 1.25, respectively (see Fig. 8). However, this had no effect on the goodness-of-fit for the visco-hyperelastic mean-parameter model, since the stretch for the second transition point was approximately 1.2 in the dynamic tests. It is worth noting that the second transition point usually serves as the onset of the collagen fiber failure process1. The elevated goodness-of-fit metrics indicate that the model captures both the initial low-strain response (largely governed by the matrix) and the subsequent, more pronounced fiber-dominated regime.

Although the present results extend the knowledge of cervical spinal ligament behavior at both quasi-static and dynamic strain rates, certain limitations should be noted. First, all tests were carried out under uniaxial tension, reflecting the dominant loading mode of these ligaments but not necessarily replicating the full complexity of in vivo conditions. In practice, conducting multi-axial or off-axis tests for such small spinal ligaments is exceedingly difficult or infeasible, primarily due to geometric and mechanical constraints. Second, the study’s sample size could be expanded to improve statistical power and capture inter-individual variability more comprehensively. Third, the donor cohort ranged from 70 to 90 years of age, so extrapolating these results to younger populations or pathological cases should be done with caution. Finally, future work might involve exploring loading rates faster than 50 s⁻¹ to further clarify ligament behavior under severe dynamic conditions, such as those experienced during high-speed impacts. Furthermore, extending the visco-hyperelastic model to the sub-failure region would allow describing ligament behavior up to the failure point. Addressing these issues would help refine and validate the visco-hyperelastic model for broader applications in cervical spine biomechanics and injury prevention.

Conclusions

This study investigated the mechanical behavior of four human cervical spine ligaments (ALL, PLL, LF, and CL) from older adult donors (70–90 years) under both low-strain (0.5 s⁻¹) and high-strain (50 s⁻¹) rate loading.

Key conclusions can be summarized as follows:

-

Strain-rate sensitivity: Ligaments such as the PLL, LF, and CL showed statistically significant increases in stiffness and elastic modulus under rapid loading. Conversely, the ALL in this study presented slightly lower stiffness at 50 s⁻¹ than at 0.5 s⁻¹. An increase in the failure force was observed only for the PLL and LF at 50 s⁻¹.

-

Age-related variations: Meta-regression indicated negative coefficients for stiffness and failure force with increasing donor age in certain cases. This finding reinforces the need to incorporate age-specific data into both clinical practice and computational models, particularly for geriatric populations.

-

Constitutive modeling: The two-step fitting protocol, extracting hyperelastic parameters from quasi-static experiments and viscous parameters from high-strain rate tests, was shown to be effective, with mean-parameter models accurately describing the average ligament response up to the second transition point.

-

Applications and future work: The presented stress–stretch data and material parameters can enhance FE and HBMs, potentially improving injury prediction in scenarios such as automotive crashes. Future research should focus on larger sample sizes, a broader range of donor demographics, and higher loading rates (> 50 s⁻¹) to further refine constitutive models and better capture ligament behavior under extreme conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw data contain identifiable donor information and are therefore not publicly deposited to protect participant confidentiality.

References

Trajkovski, A., Omerović, S., Hribernik, M. & Prebil, I. Failure properties and damage of cervical spine Ligaments, experiments and modeling. J. Biomech. Eng. 136, 031002, (2014).

Trajkovski, A., Hribernik, M., Kunc, R., Kranjec, M. & Krašna, S. Analysis of the mechanical response of damaged human cervical spine ligaments. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 75, 105012 (2020).

Ito, S., Ivancic, P. C., Panjabi, M. M. & Cunningham, B. W. Soft tissue injury threshold during simulated whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 29, 979–987 (2004).

Pachocki, L., Daszkiewicz, K., Łuczkiewicz, P. & Witkowski, W. Biomechanics of lumbar spine injury in road barrier Collision–Finite element study. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol 9, 760498 (2021).

Przybylski, D., Gregory, J. C., Prakash, R. P. & Savio, L. Y. W. Human anterior and posterior cervical longitudinal ligaments possess similar tensile properties. J. Orthop. Res. 14, 1005–1008 (1996).

Myklebust, J. B. et al. Tensile strength of spinal ligaments. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 5, 526–531 (1988).

Yoganandan, N., Kumaresan, S. & Pintar, F. A. Geometric and mechanical properties of human cervical spine ligaments. J. Biomech. Eng. 122, 623–629 (2000).

Bass, C. R. et al. Failure properties of cervical spinal ligaments under fast strain rate deformations. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 32, 7–13 (2007).

Ivancic, P. C. et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of intact human cervical spine ligaments. Spine J. 7, 659–665 (2007).

Mattucci, S. F. E., Moulton, J. A., Chandrashekar, N. & Cronin, D. S. Strain rate dependent properties of younger human cervical spine ligaments. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 10, 216–226 (2012).

Trajkovski, A., Omerovic, S., Krasna, S. & Prebil, I. Loading rate effect on mechanical properties of cervical spine ligaments. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 16, 13–20 (2014).

Butler, F. et al. Static and Dynamic Comparison of Human Cervical Spinal Ligaments. in IEEE Engineering In Medicine & Biology Society 10th Annual International Conference (1988).

Cowin, S. C. & Doty, S. B. Tissue Mechanics (Springer, 2007).

Östh, J., Brolin, K., Svensson, M. Y. & Linder, A. A female ligamentous cervical spine finite element model validated for physiological loads. J. Biomech. Eng. 138, 061005 (2016).

Dreischarf, M. et al. Comparison of eight published static finite element models of the intact lumbar spine: predictive power of models improves when combined together. J. Biomech. 47, 1757–1766 (2014).

John, J. et al. world! VIVA+: A human body model lineup to evaluate sex-differences in crash protection. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 1–19 (2022).

Cameron, M. W., Schemitsch, E. H., Zdero, R. & Quenneville, C. E. Biomechanical impact testing of synthetic versus human cadaveric tibias for predicting injury risk during pedestrian-vehicle collisions. Traffic Inj Prev. 21, 163–168 (2020).

Corrales, M. A., Cronin, D. S. & Sex Age and stature affects neck Biomechanical responses in frontal and Rear impacts assessed using finite element head and neck models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 681134 (2021).

Bass, C. R., Lucas, S. R. & Salzar, R. S. Injury biomechanics of the cervical spine. J. Biomech. 39, S195–S202 (2006).

Woo, S. L. Y., Hollis, J. M., Adams, D. J., Lyon, R. M. & Takai, S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. Am. J. Sports Med. 19, 217–225 (1991).

Wiczenbach, T., Pachocki, L., Daszkiewicz, K., Łuczkiewicz, P. & Witkowski, W. Development and validation of lumbar spine finite element model. PeerJ 11, 15805 (2023).

Östh, J., Brolin, K. & Bråse, D. A. Human body model with active muscles for simulation of pretensioned restraints in autonomous braking interventions. Traffic Inj Prev. 16, 304–313 (2015).

Iwanaga, J. et al. Acknowledging the use of human cadaveric tissues in research papers: recommendations from anatomical journal editors. Clin. Anat. 34, 2–4 (2021).

Wolny, R., Wiczenbach, T., Andrzejewska, A. J. & Spodnik, J. H. Mechanical response of human thoracic spine ligaments under quasi-static loading: an experimental study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 106404 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2024.106404 (2024).

Wolny, R., Wiczenbach, T., Pachocki, L., Wilde, K. & Rucka, M. The role of sand filler in enhancing the mechanical properties of polymethylmethacrylate composites. Archives Mech. 77, 53–66 (2025).

Cheng, S., Clarke, E. C. & Bilston, L. E. The effects of preconditioning strain on measured tissue properties. J. Biomech. 42, 1360–1362 (2009).

Mattucci, S. F. E. & Cronin, D. S. A method to characterize average cervical spine ligament response based on Raw data sets for implementation into injury biomechanics models. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 41, 251–260 (2015).

Fazlali, H., Sadeghi, H., Sadeghi, S., Ojaghi, M. & Allard, P. Comparison of four methods for determining the cut-off frequency of accelerometer signals in able-bodied individuals and ACL ruptured subjects. Gait Posture. 80, 217–222 (2020).

Society of Automotive Engineers. Instrumentation for Impact Test - Part 1 - Electronic Instrumentation. SAE J211-1 Preprint at. (1995).

Limbert, G. & Middleton, J. A transversely isotropic viscohyperelastic material: application to the modeling of biological soft connective tissues. Int. J. Solids Struct. 41, 4237–4260 (2004).

Sabik, A. & Witkowski, W. On implementation of fibrous connective tissues’ damage in Abaqus software. J. Biomech. 111736 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111736 (2023).

Martins, J. A. C., Pires, E. B., Salvado, R. & Dinis, P. B. A numerical model of passive and active behavior of skeletal muscles. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 151, 419–433 (1998).

Abaqus Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp. Abaqus Theory Guide. (2023).

Zhurov, A. I., Limbert, G., Aeschlimann, D. P. & Middleton, J. A constitutive model for the periodontal ligament as a compressible transversely isotropic visco-hyperelastic tissue A constitutive model for the periodontal ligament as a compressible transverse. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080701314894 (2007).

Jiang, Y., Wang, Y. & Peng, X. A. Visco-Hyperelastic constitutive model for human spine ligaments. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 71, 1147–1156 (2015).

Holzapfel, G. A. Nonlinear Solid Mechanics: A Continuum Approach for Engineering (Wiley, 2000).

Seabold, S., Perktold, J. & statsmodels Econometric and statistical modeling with python. at < www.statsmodels.org> (2010).

Mattucci, S. F. E. Biomechanical characterization of cervical spine ligaments in young populations. J. Biomech. 47, 3251–3256 (2014).

Kalichman, L. & Hunter, D. J. Lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis: A review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 37, 69–80 (2007).

Fujiwara, A. et al. Orientation and osteoarthritis of the lumbar facet joint. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 385, 88–94 (2001).

Koeller, W., Muehlhaus, S., Meier, W. & Hartmann, F. Biomechanical properties of human intervertebral discs subjected to axial dynamic compression—Influence of age and degeneration. J. Biomech. 19, 807–816 (1986).

Schleifenbaum, S. et al. Tensile properties of the hip joint ligaments are largely variable and age-dependent – An in-vitro analysis in an age range of 14–93 years. J. Biomech. 49, 3437–3443 (2016).

Barros, E. M. K. P. et al. Aging of the elastic and collagen fibers in the human cervical interspinous ligaments. Spine J. 2, 57–62 (2002).

Hulme, P. A., Boyd, S. K. & Ferguson, S. J. Regional variation in vertebral bone morphology and its contribution to vertebral fracture strength. Bone 41, 946–957 (2007).

Belavý, D. L., Armbrecht, G., Richardson, C. A., Felsenberg, D. & Hides, J. A. Muscle atrophy and changes in spinal morphology. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 36, 137–145 (2011).

Bogduk, N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 50, 613–628 (2012).

Lee, S. H. et al. The sagittal balance of cervical spine: comprehensive review of recent update. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 66, 611–617 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deepest gratitude to the individuals who selflessly donated their bodies to science and to their families for supporting this invaluable gift. Such generosity enables anatomical research that advances medical knowledge and ultimately improves patient care.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Centre Poland under grant number 2020/37/B/ST8/03231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RW, TW: Conceptualisation, Data Curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing - Original Draft. LP, AA-S. AS, KD: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Review and Editing. BM: Conceptualisation, Methodology. MR, WW: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – Review and Editing. KW: Funding Acquisition. ES, JHS, IK, PŁ: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures involving human specimens were performed in compliance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdańsk (Ordinance No. 26/2016). The specimens were obtained through a body donation program with appropriate donor consent for scientific use.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wolny, R., Wiczenbach, T., Pachocki, L. et al. Experimental evaluation and constitutive modelling of cervical spine ligaments under low and high strain rates. Sci Rep 15, 40139 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23918-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23918-8