Abstract

The soil fungus Penicillium gladioli was identified by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy of the extract showed 50 compounds. Among the detected peaks, n-hexadecanoic acid showed the largest relative peak area (7.989% of the total ion chromatogram), followed by phenol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl) (6.543%). Regarding the in vivo anti-toxoplasma potential, there was an enhancement of the histological features of the liver of Swiss albino mice with a substantial decrease (p < 0.05) in the inflammatory mediators, including cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β. The colorimetric determination of the nitric oxide and malondialdehyde in the liver of the fungal extract-treated group revealed its antioxidant effect by significantly reducing (p < 0.05) the oxidative stress markers. P. gladioli extract established antibacterial potential on P. aeruginosa bacteria with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 64 to 512 µg/ml. Moreover, it demonstrated antibiofilm potential using crystal violet assay and SEM. Also, 45% of the isolates displayed downregulation of the lasR, lecA, and pelA biofilm genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diverse microorganisms are present in the soil, and they can adapt to environmental conditions by yielding various natural substances or metabolites to deal with harsh habitat characteristics1. Owing to their great pharmacological activities, such metabolites could be employed as pharmaceutical products. Fungi constitute a large proportion of soil microbes and can produce many bioactive compounds. Therefore, saprophytic fungi are a sustainable source of various compounds with different biological activities1.

Toxoplasma gondii is an a parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, an ailment affecting millions of people2. Usually, acute toxoplasmosis is followed by asymptomatic latent infection, and T. gondii encysts in several organs. Such latent infections often reactivate in the immunocompromised hosts, triggering severe fatal illness if left untreated3.

Owing to available treatment options still hampered by severe adverse effects, there is a strong push to develop other new options of therapy for toxoplasmosis. Consequently, there is a crucial necessity to find innovative anti-toxoplasma drugs or to improve the existing ones4,5.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a pathogenic bacterium with various virulence factors, like biofilm formation. Biofilm is a group of bacterial cells in an extracellular matrix. The biofilm formation facilitates the communication between bacterial cells and resistance gene transfer. In addition to the multiple virulence factors of P. aeruginosa, it can resist multiple traditional antibiotics. The recent rising antibiotic resistance rates among bacteria have elicited a great demand to seek alternative chemicals from natural origin to overcome drug-resistant microbes6.

Soil is a suitable environment for the growth of various microbes. So, it is highly explored to elucidate microorganisms that have the capability to yield valuable bioactive products, like antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic agents7.

Thus, much research was performed to evaluate the potential antibacterial and antivirulence action of different natural substances8. Saprophytic fungi like Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, and Emericella nidulans9 could produce various secondary metabolites that possess antibacterial action.

From this point of view, the anti-toxoplasma and antibacterial effects of the saprophytic fungi Penicillium gladioli extract were investigated in infected mice with virulent RH HXGPRT(−) strain of T. gondii and P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, respectively. An illustrative representation of the current investigation’s framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Isolation of fungi from soil samples

Five grams of different samples of soil were gathered in sterile polythene bags from Tanta, Egypt, at various locations. In the microbiology laboratory, the soil samples were diluted in sterile water (1 g of soil in 10 mL of water). Then, the prepared suspension was added to potato dextrose agar (PDA, Oxoid, USA) plates, which were incubated at 28 °C for 1 week. Then, isolation of the pure fungal culture was performed on PDA plates10.

Identification of the saprophytic fungi

The isolated saprophytic fungus was obtained as a pure culture on PDA plates11 to be recognized by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region12. The sequence of the utilized primer was 5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′ in the forward direction and 5′-TCCTCCGCT TATTGATATGC-3′ in the reverse direction. The sequences of the amplified products were determined at Macrogen Co., Korea. Then, the resulting sequences were deposited in the Gene Bank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) under the accession number PV893029. The BLAST analysis revealed 100% identity with Penicillium gladioli (accession number AF033480). Using the MEGA 7.0 program, a phylogenetic tree was constructed.

Preparation of the fungal fermentation broth

The identified saprophytic fungal isolate was cultivated at 25 °C for 10 days in a potato dextrose liquid, and the ethyl acetate fungal extract was prepared, as previously explained13. The crude fermentation broth was thoroughly blended for the selected isolate (107 CFU/ml) and centrifuged. Liquid supernatant was extracted with an equal amount of ethyl acetate and repeated three times. The organic solvent extract was then evaporated under reduced pressure to yield the crude metabolite for screening its anti-toxoplasma and antibacterial activities.

Identification of bioactive metabolites by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

The Perkin Elmer model (Clarus 580/560 S) was employed in the column analysis (Rxi-5Sil MS column 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 df), employing helium as a carrier gas14. During the chromatographic run, the temperature of the injector was set at 280 °C. One microliter of the fungal extract was injected into the scanning instrument for 30 min, with an initial oven temperature of 60° C for 10 min, ramp of 10 °C/min to 280 °C for 6 min, split 20:1, solvent delay, 3 min. The conditions for the mass detector were transferred line temperature of 280 °C, ion source temperature of 200 °C, and the effect of ionization mode at 70 eV, a scan time of 0.2 s, and a scan interval of 0.1 s. Given fragments from 50 to 600 Da, the component spectrum was compared with the spectrum database of recognized components held in the GC-MS NIST library.

Parasite

The virulent RH HXGPRT(−) strain of T. gondii was obtained from the medical parasitology department, faculty of medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt, and it was conserved by its serial passage in Swiss albino mice15.

Experiment

Thirty-six Swiss albino mice (4–6 weeks old, weighing 20–25 g) were obtained from Alexandria University. The mice were retained in conditions of 23 ± 2 °C/45–55% relative humidity. Essential procedures were performed to provide proper care. The procedures were accepted by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt (approval number 0306733).

The mice were randomly grouped into three groups (each composed of 12 mice).

Group I was intra-peritoneally (IP) infected with 3500 tachyzoites of T. gondii, and it wasn’t treated.

Group II was IP infected with 3500 tachyzoites of T. gondii and then treated orally with spiramycin (Medical Union Pharmaceuticals, Egypt, 200 mg/kg/day) for five days5.

Group III was IP infected with 3500 tachyzoites of T. gondii and then treated orally with P. gladioli fungal extract (150 mg/kg/day) for five days16.

On the sixth day, half of the mice from all groups were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after anaesthesia by isoflurane inhalation, and the rest were employed to calculate the survival rate17.

Anti-toxoplasma effect of P. gladioli fungal extract.

The survival time and rate were estimated as previously reported18. The mean count of the tachyzoites was detected in one milliliter of the peritoneal fluid by a hemocytometer (HBG®- Germany)19. The parasite burden percent reduction (%R) was revealed in the experimental groups15 employing the formula:

Scanning electron microscopic study (SEM)

Tachyzoites of T. gondii from the peritoneal exudates of mice from the different experimental groups were prepared for SEM examination, as previously reported19, to elucidate the consequence of the fungal extract on the parasite’s ultrastructure.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical elucidation

As previously explained, liver from mice was preserved in 10% formalin for histopathological study20 after staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-schiff (PAS) stain20,21. The immunohistochemical investigations were achieved using the monoclonal antibodies for cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) as previously reported22.

Colorimetric investigation

Colorimetric kits (Biodiagnostics, Egypt) were employed to measure the nitric oxide (NO) and malondialdehyde (MDA) in the liver at 540 nm.

Antibacterial effect

It was illuminated by the agar well diffusion method in Muller-Hinton agar plates, employing ciprofloxacin (2 µg/mL) and DMSO, as positive and negative controls, respectively23,24,25. Twenty P. aeruginosa clinical isolates were tested and obtained from the pharmaceutical microbiology department, faculty of pharmacy, Tanta University. Then, after revealing the antibacterial action by measuring the diameters of the inhibition zones around the wells, the MICs were determined using 96-well microtitration plates, as formerly clarified25.

Antibiofilm action

The capacity of the fungal extract to hinder the ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilm was elucidated using crystal violet assay in microtitration plates26. Also, the consequence of the fungal extract on the biofilm gene expression (lasR, lecA, and pelA) was investigated using qRT-PCR. The antibiofilm action of the fungal extract was elucidated using the crystal violet assay (at 0.5 MIC values) on the biofilm formation ability of P. aeruginosa isolates. The values of the optical density (OD) were determined at 590 nm using ELISA reader. Then, the capability of tested isolates to form biofilm was grouped into four classes as follows: Non-biofilm former isolates (ODc < OD < 2 ODc), weak biofilm former isolates (2 ODc < OD < 4 ODc), moderate biofilm former isolates (4 ODc < OD < 6 ODc), and strong biofilm former isolates (6 ODc < OD). The cut-off OD (ODc) was identified as the product of the addition of the mean OD to three standard deviation (SD) of the negative control.

The effect of the fungal extract was studied on the expression levels of the biofilm genes (lasR, lecA, and pelA) by qRT-PCR. After growing the isolates in TSB in the presence and absence of 0.5 MICs, they were incubated overnight at 37 °C. After the incubation period, cells were harvested by centrifugation and immediately stored at − 80 °C. The total RNA from P. aeruginosa isolates was extracted and purified using TRIzol® reagent (Life Technologies, USA) following the manufacturer protocol. Reverse transcription was employed using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Germany). After that, the formed cDNA was amplified using Maximas SYBR Green/Fluorescein qPCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

The average threshold cycle (CT) values were normalized to the housekeeping gene (16s rRNA). The relative gene expression of the treated isolates was compared to that in the untreated ones according to the 2−∆∆Ct method27. Primers are listed in Table S128,29.

The antibiofilm activity of the fungal extract was further revealed using SEM. Briefly, cover slips in six-well plates were inoculated with P. aeruginosa bacteria suspension (107 CFU/mL) and incubated overnight at 37 °C under two conditions: (i) medium alone (control, without the fungal extract) and (ii) medium supplemented with the fungal extract at 0.5 MIC values. After incubation, the coverslips were gently rinsed with sterile phosphate buffer to remove planktonic cells. For SEM preparation, samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, rinsed, and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. Dehydration was performed through a graded ethanol series, and the specimens were then dried, mounted on aluminium stubs, and sputter-coated with a gold-palladium layer. Imaging was performed using SEM (Hitachi, Japan), and representative micrographs were acquired30,31.

Statistics

Quantitative data were designated as mean ± standard deviation (SD) using GraphPad Prism software (USA). The significance was referred to at p < 0.05. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed for abnormally distributed quantitative variables to compare more than two studied groups, followed by Bonferroni for comparing each two groups. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve and the Chi-square for the log-rank test for significant survival were also used.

Results

P. gladioli fungus

The obtained fungal culture was identified by ITS region sequencing as P. gladioli (Fig. S1 and Table 1).

GC-MS

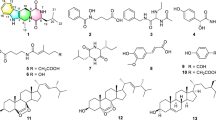

Bioactive metabolites were identified by GC-MS exploration, as GC-MS is considered one of the best procedures for differentiating the constituents of volatile matter, acids of alcohols, long chains, branched hydrocarbons, and esters. The compounds’ retention time (Rt) and peak area percentage are presented in Table 2; Fig. 2.

Parasitological results

Survival time and survival rate

No mortality was detected on the day of scarification (the 6th day post-infection) in all groups. All six mice in the control group (group I) died on the 7th day. In the spiramycin-treated group (group II), four of the six mice died on the 7th day (66.7% survived mice) and one on the 8th day (16.7% survived mice) with a mean of 7.83 days. In the P. gladioli extract-treated group (group III), none of the six mice died on the 7th day (100% survived mice), and three on the 8th day (50% survived mice) with a mean of 8.5 days. The prolonged survival time in group III was substantial (p < 0.001) in comparison to the non-treated control group (group I) and the spiramycin-treated group (group II) (Fig. 3, Table S2).

Mean number of tachyzoites of T. gondii.

In comparison to group I (mean ± SD = 545.5 ± 343.0), treated groups displayed a noteworthy decline (p < 0.001) in the tachyzoites count, with a mean ± SD of 22.2 ± 21.4 and 36.3 ± 26.4 with a reduction of 95.9% and 93.3% in group II (spiramycin) and group III (P. gladioli extract), respectively (Table 3).

SEM

SEM of T. gondii tachyzoites attained from the peritoneal fluid of the untreated group (group I) exposed normal-sized crescent-like tachyzoites with smooth surfaces (Fig. 4A). In contrast, group II, treated with spiramycin, showed an increase in the tachyzoites’ size in the form of ballooning with surface irregularities and coarse ridges (Fig. 4B). Likewise, in the P. gladioli extract-treated group (group III), tachyzoites increased in size with surface irregularities, a tear in the upper end, and a bulge in the lower end (Fig. 4C). Tachyzoites in Fig. 4D showed surface ridges and depressions.

The scanning electron micrograph of T. gondii tachyzoites (×15000). Tachyzoites in group I (Positive control) showed a normal size, shape, and surface (A). Group II (Spiramycin group) showed an increase in the size with coarse surface ridges (B). Group III (Fungal extract group) showed an increased size with surface irregularities, such as a tear in the upper end and a bulge in the lower end (C). In addition, group III (D) revealed surface ridges and depressions.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical results

Figures 5 and 6 reveal the liver histological features of the different groups. Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10 also reveal COX-2, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β immunohistochemical reactions.

Analysis of liver architecture by H&E staining. (A,B) Group I (Positive control) shows a loss of the normal hepatic architecture, compressed hepatic sinusoids, multiple pyknotic nuclei (black arrow), multiple karyolitic nuclei (dashed black arrow), and diffuse vacuolar degeneration of hepatocytes with multiple large vacuoles (V) and ballooned hepatocytes. (C–F) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) show marked improvement and regaining of the normal hepatic structure in the form of organized hepatic architecture with hepatic cords (c) radiating from the central vein (CV) and separated by the hepatic sinusoids (S) with pericentral zone and midzone hepatocytes. Polyhedral hepatocytes appear with rounded vesicular nuclei and granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (black arrow) separated by sinusoids (S) which are lined with endothelial cells and Kupffer cells. Also, portal triad (PT) and some inflammatory cells (blue arrow) can be seen in group III (Fungal extract group) (E).

Analysis of liver glycogen by PAS staining. (A) Group I (Positive control) expresses weak PAS-positive cells. (B,C) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) express a strong PAS cytoplasmic stain (glycogen) in the hepatocytes around the central veins. (D) Area percentage of PAS-positive cells in all groups. The single asterisk designates a substantial (p < 0.05) difference, and the abbreviation (NS) designates a non-significant (p > 0.05) difference where n = 10. (PAS × 400, scale bar = 50 μm).

COX-2 immunohistochemical staining analysis of liver sections. (A) Group I (Positive control) expresses a strong positive COX-2 reaction in the form of brown stain within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (yellow arrows) with a significant difference from both groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group). (B,C) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) show few COX-2 positive cells (yellow arrow) and a negative reaction in most cells with non-significant difference with each other. (D) Area percentage of COX-2 immune reaction in all groups. The single asterisk designates a substantial (p < 0.05) difference, and the abbreviation (NS) designates a non-significant (p > 0.05) difference where n = 10. (COX-2 × 400, scale bar = 50 μm).

TNF-α immunohistochemical staining analysis of liver sections. (A) Group I (Positive control) expresses a strong positive TNF-α reaction in the form of brown stain within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (yellow arrows) with a significant difference from both group II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group). (B,C) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) show few TNF-α positive cells (yellow arrow) and negative reaction in the most of cells with a non-significant difference from each other. (D) Area percentage of TNF-α immune reaction in all groups. The single asterisk designates a substantial (p < 0.05) difference, and the abbreviation (NS) designates a non-significant (p > 0.05) difference where n = 10. (TNF-α × 400, scale bar = 50 μm).

IL-6 immunohistochemical staining analysis of liver section. (A) Group I (Positive control) expresses a strong IL-6 positive reaction in the form of brown stain within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (yellow arrows) with a significant difference from both groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group). (B,C) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) show few IL-6 positive cells (yellow arrow) and a negative reaction in most cells with a non-significant difference from each other. (D) Area percentage of IL-6 immune reaction in all groups. The single asterisk designates a substantial (p < 0.05) difference, and the abbreviation (NS) designates a non-significant (p > 0.05) difference where n = 10. (IL-6 × 400, scale bar = 50 μm).

IL-1β immunohistochemical staining analysis of liver section. (A) Group I (Positive control) expresses a strong IL-1β positive reaction in the form of brown stain within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (yellow arrows) with a significant difference from groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group). (B,C) Groups II (Spiramycin group) and III (Fungal extract group) show few IL-1β positive cells (yellow arrow) and a negative reaction in the most of cells with a non-significant difference from each other. (D) Area percentage of IL-1β immune reaction in all groups. The single asterisk designates a substantial (p < 0.05) difference, and the abbreviation (NS) designates a non-significant (p > 0.05) difference where n = 10. (IL-1β × 400, scale bar = 50 μm).

Colorimetric results

As oxidative stress markers, NO and MDA levels were noticeably diminished (p < 0.05) in group III compared to group I, as exposed in Fig. 11. This outcome designates the antioxidant consequence of the fungal extract, which helps it in the anti-toxoplasma consequence to alleviate the detrimental effects of the infection.

Antibacterial potential of the fungal extract on P. aeruginosa isolates

The fungal extract exposed inhibition zones around the wells, as shown in Fig. 12. The MICs of the fungal extract ranged from 64 to 512 µg/ml (Table 4).

Antibiofilm action

About 65% of P. aeruginosa isolates were able to form biofilm strongly or moderately. Remarkably, the fungal extract considerably declined this percentage to 20% (Table 5).

Figure 13 exposes the result of P. gladioli on the biofilm gene expression, as it downregulated the biofilm-related genes in 45% of the isolates.

SEM was utilized to illuminate the consequence of the fungal extract on the bacterial biofilm. As shown in Fig. 14, a noteworthy decline in the number of the biofilm-forming isolates was found after treatment with P. gladioli extract.

Discussion

Soil is regarded as one of the most appropriate environments for the growth of many microbes, like bacteria and fungi. Here, the saprophytic fungus, P. gladioli, was isolated and identified from a soil sample from Tanta, Egypt. We investigated its anti-toxoplasma and antibacterial action as the fungal extract represents a sustainable and eco-friendly source of various active compounds.

A remarkable number of the natural product-derived drugs originate from microbes or plants32. Natural products from microbes, like fungi, are a significant source of many antibacterial and anti-parasitic agents. This is attributed to the abundant diversity of the fungal species and their numerous secondary metabolites. They are better than plants as they don’t necessitate different land and water resources and can yield a vast biomass with a low cost33.

GC-MS is an efficient method for recognizing constituents in natural extracts34. Thus, we employed GC-MS to elucidate the bioactive chemicals in the ethyl acetate fungal extract, revealing the presence of 50 compounds. Among the detected peaks, n-hexadecanoic acid showed the largest relative peak area (7.989% of the total ion chromatogram), followed by phenol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl) (6.543%). Antibacterial and anti-toxoplasma activities of the fungal extract may be related to these active compounds. Kalariya et al.35 documented the antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-parasitic actions of naphthalene derivatives produced by P. gladioli. Similarly, Oliveira et al.36. stated the anti-leishmanial activity of naphthalene derivatives. Donger et al.37 found that undecenal possessed antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activities. Shaaban et al.38 have also designated an antimicrobial consequence of hexadenoic acid against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Also, it was demonstrated by Lalthanpuii et al.39 that hexadecanoic acid was effective against the tapeworm Raillietina echinobothrida.

Based on the inadequate therapeutic choices, many adverse effects, and the risk of emergence of many resistant parasites, several researchers have considered medicinal natural extracts as potential safe new drugs for treating toxoplasmosis40,41. Various bioactive compounds from the fungi extract have demonstrated diverse pharmacological effects against different microbes42. Here, the anti-parasitic effect of P. gladioli on T. gondii was elucidated in mice. The longest survival time was reported in the P. gladioli extract-treated group (group III) with a mean of 8.5 days, which was statistically noteworthy (p < 0.05) in comparison to the non-treated control (group I) and spiramycin-treated group (group II). Almallah et al.18. documented a boosted survival rate of mice infected with T. gondii treated with probiotics as a safe, natural tested agent.

Regarding the parasite load, the treated groups exhibited a noteworthy decline (p < 0.05) in the mean count of tachyzoites in the peritoneal fluid compared to group I. The significant decline was 93.3% in the P. gladioli extract-treated group (group III) with a mean ± SD of 36.3 ± 264 in comparison to the group I with a mean ± SD of 545.5 ± 343.0. This reduction in the percentage of parasite count is consistent with the results of different recent investigations accomplished on T. gondii tachyzoites4,17,18,19,43,44,45.

Several bioactive agents formed by saprophytic fungi can lessen reactive oxygen species levels, subsequently decreasing inflammation46,47,48,49. The main cause of the mice’s bad clinical condition and death is the severe inflammation produced in the vital organs by the massive parasite replication46. Here, the fungal extract-treated group showed a noteworthy diminishing in the immunostaining of COX-2, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, which are inflammatory markers. This lessening in the inflammatory mediators could be related to the decrease in the parasite-induced tissue damage. The fungal extract could have anti-inflammatory potential on its own, but this point necessitates further studies to establish whether the extract exerts a direct immunomodulatory effect. Previous reports have described the potential anti-inflammatory action of fungal extracts50,51.

SEM elucidation of the tachyzoites in the peritoneal fluid of P. gladioli extract-treated group (group III) showed a distortion in the tachyzoites’ shape and irregularities of their surface in the form of bulges, ridges, and depressions. These changes demonstrated the effect of the oral inoculation of the fungal extract on the tachyzoites in the peritoneal fluid. The adequate bioavailability of the extract allowed its presence in tissue in sufficient amounts that could affect the parasites15. Additionally, the surface distortion at the ultrastructural level could have reduced the reproduction of the tachyzoites, which was a principal cause of the significant decrease in the parasite load52.

The P. gladioli fungal extract revealed antibacterial action on the tested P. aeruginosa isolates. This could be attributed to the bioactive chemicals in the fungal extract. Ganesan et al.53 described the antibacterial action of n-hexadecanoic acid on Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Also, Sajayan et al.54. documented the antibacterial and antibiofilm action of n-hexadecanoic acid from marine sponge-associated bacteria Bacillus subtilis. Many studies have documented the antibacterial action of phenolic compounds like phenol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl)55,56,57. The chief mechanism of action of phenolic compounds is the disruption of the bacterial membranes.

Biofilms are reported to be involved in more than 60% of human infections58. Therefore, substantial research has focused on finding antibiofilm compounds. In P. aeruginosa, biofilm formation relies mostly on the communication between cells by quorum-sensing (QS) controlled by QS genes like lasR59. Also, P. aeruginosa can produce a cytotoxic lectin expressed by the lecA gene in the biofilm-forming cells. In addition, the lecA gene is important in the biofilm architecture as it is involved in the extracellular matrix, which controls the biofilm structural integrity. The pelA gene plays a noteworthy role in forming the carbohydrate-rich structure in biofilm60. Here, we inspected the antibiofilm outcome of the fungal extract by crystal violet, SEM, and qRT-PCR. It elucidated a remarkable antibiofilm action as it downregulated the biofilm-related genes in 45% of the isolates. One of the limitations in our study is employing GC-MS analysis for chemical profiling of the fungal extract, as it is limited to volatile and semi-volatile constituents, and thus other non-volatile compounds with potential biological activity may not have been detected. The individual compounds in the crude fungal extract will be elucidated for their own anti-toxoplasma and antibacterial potentials in our future studies. Figure 15 represents the experiments conducted in this study.

Conclusion

The current work suggests that P. gladioli could serve as a new alternate treatment for acute toxoplasmosis and P. aeruginosa infections. It revealed a detrimental impact on the parasite in vivo and bacteria in vitro. It could also be investigated on other parasites and bacterial species. Future clinical studies should also be performed on this saprophytic fungus to illuminate its effectiveness in clinical settings.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and the supplementary information.

References

Usman, M. et al. Synergistic partnerships of endophytic fungi for bioactive compound production and biotic stress management in medicinal plants. Plant Stress. 100425 (2024).

Szewczyk-Golec, K., Pawłowska, M., Wesołowski, R., Wróblewski, M. & Mila-Kierzenkowska, C. Oxidative stress as a possible target in the treatment of toxoplasmosis: perspectives and ambiguities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5705 (2021).

Al-Malki, E. S. Toxoplasmosis: stages of the protozoan life cycle and risk assessment in humans and animals for an enhanced awareness and an improved socio-economic status. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 962–969 (2021).

El-Kady, A. M. et al. Ginger is a potential therapeutic for chronic toxoplasmosis. Pathogens 11, 798 (2022).

El-Kady, A. M. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles produced by Zingiber officinale ameliorates acute toxoplasmosis-induced pathological and biochemical alterations and reduced parasite burden in mice model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011447 (2023).

Helmy, Y. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance and recent alternatives to antibiotics for the control of bacterial pathogens with an emphasis on foodborne pathogens. Antibiotics 12, 274 (2023).

Kumar, C. G., Mongolla, P., Joseph, J., Nageswar, Y. & Kamal, A. Antimicrobial activity from the extracts of fungal isolates of soil and Dung samples from Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India. J. De Mycol. Médicale. 20, 283–289 (2010).

Tuon, F. F. et al. Antimicrobial treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antibiotics 12, 87 (2023).

Sheikh, H. .S. Antimicrobial activity of certain bacteria and fungi isolated from soil mixed with human saliva against pathogenic microbes causing dermatological diseases. 17, 331–339 (2010).

Lee, J., Kim, H. S., Jo, H. Y. & Kwon, M. J. Revisiting soil bacterial counting methods: optimal soil storage and pretreatment methods and comparison of culture-dependent and-independent methods. PLoS One. 16, e0246142 (2021).

Abdelwahab, G. M. et al. Acetylcholine esterase inhibitory activity of green synthesized nanosilver by Naphthopyrones isolated from marine-derived Aspergillus niger. PloS One. 16, e0257071 (2021).

Ababutain, I. M. et al. Identification and antibacterial characterization of endophytic fungi from Artemisia sieberi. Int. J. Microbiol. (2021).

Devi, N. & Prabakaran, J. Bioactive metabolites from an endophytic fungus penicillium sp. isolated from centella Asiatica. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 4, 34–43 (2014).

Ms, R. & Pushpa, K. Research Phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of leaf extract of pergularia daemia (Forssk) Chiov. Asian J. Plant. Sci. (2017).

El-Zawawy, L. A., El-Said, D., Mossallam, S. F., Ramadan, H. S. & Younis, S. S. Triclosan and triclosan-loaded liposomal nanoparticles in the treatment of acute experimental toxoplasmosis. Exp. Parasitol. 149, 54–64 (2015).

Saleh, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory potential of penicillium brefeldianum endophytic fungus supported with phytochemical profiling. Microb. Cell. Fact. 22, 83 (2023).

Moglad, E. et al. Momtaz Al-Fakhrany, O. Antibacterial and anti-Toxoplasma activities of Aspergillus niger endophytic fungus isolated from ficus retusa: in vitro and in vivo approach. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 51, 297–308 (2023).

Almallah, T. M. et al. The synergetic potential of Lactobacillus delbrueckii and Lactobacillus fermentum probiotics in alleviating the outcome of acute toxoplasmosis in mice. Parasitol. Res. 122, 927–937 (2023).

Eid, R. K. et al. Surfactant vesicles for enhanced Antitoxoplasmic effect of norfloxacin: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Int. J. Pharm. 638, 122912 (2023).

Al-Kuraishy, H. M. et al. Potential therapeutic benefits of Metformin alone and in combination with sitagliptin in the management of type 2 diabetes patients with COVID-19. Pharm 15, 1361 (2022).

Al-Kuraishy, H. M., Al-Gareeb, A. I., Elekhnawy, E. & Batiha, G. E. S. Nitazoxanide and COVID-19: a review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 11169–11176 (2022).

Alqahtani, M. J., Elekhnawy, E., Negm, W. A., Mahgoub, S. & Hussein, I. A. Encephalartos villosus Lem. Displays a strong in vivo and in vitro antifungal potential against Candida glabrata clinical isolates. J. Fungi. 8, 521 (2022).

Abdel Bar, F. M. et al. Anti-quorum sensing and anti-biofilm activity of Pelargonium× hortorum root extract against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: combinatorial effect of Catechin and Gallic acid. Molecules. 27, 7841 (2022).

Elekhnawy, E., Sonbol, F., Abdelaziz, A. & Elbanna, T. An investigation of the impact of triclosan adaptation on proteus mirabilis clinical isolates from an Egyptian university hospital. Braz. J. Microbiol. 52, 927–937 (2021).

Attallah, N. G. et al. Promising antiviral activity of Agrimonia pilosa phytochemicals against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 supported with in vivo mice study. Pharm. 14, 1313. (2021).

Attallah, N. G. et al. Anti-biofilm and antibacterial activities of Cycas media R. Br secondary metabolites: in silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches. Antibiotics. 11, 993 (2022).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Mastoor, S. et al. Analysis of the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity of natural compounds and their analogues against Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Molecules. 27, 6874 (2022).

Nejabatdoust, A., Zamani, H. & Salehzadeh, A. Functionalization of ZnO nanoparticles by glutamic acid and conjugation with Thiosemicarbazide alters expression of efflux pump genes in multiple drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 25, 966–974 (2019).

Sonbol, F. I., El-Banna, T., Abd El‐Aziz, A. A. & El‐Ekhnawy, E. Impact of triclosan adaptation on membrane properties, efflux and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 126, 730–739 (2019).

Relucenti, M. et al. Microscopy methods for biofilm imaging: focus on SEM and VP-SEM pros and cons. Biology. 10, 51 (2021).

Patra, J. K. et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 16, 1–33 (2018).

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 770–803 (2020).

Chikowe, I., Bwaila, K. D., Ugbaja, S. C. & Abouzied, A. S. GC–MS analysis, molecular docking, and Pharmacokinetic studies of Multidentia crassa extracts’ compounds for analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities in dentistry. Sci. Rep. 14, 1876 (2024).

Kalariya, R. N. et al. New amino acids naphthalene scaffolds as potent antimicrobial agents: in vitro assay and in Silico molecular Docking study. ChemistrySelect 9, e202400338 (2024).

Oliveira, L. F. G. et al. Antileishmanial activity of 2-methoxy-4H-spiro-[naphthalene-1, 2′-oxiran]-4-one (Epoxymethoxy-lawsone): a promising new drug candidate for leishmaniasis treatment. Molecules 23, 864 (2018).

Dongre, P., Doifode, C., Choudhary, S. & Sharma, N. Botanical description, chemical composition, traditional uses and Pharmacology of citrus sinensis: an updated review. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 8, 100272 (2023).

Shaaban, M. T., Ghaly, M. F. & Fahmi, S. M. Antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid Methyl ester and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles against multidrug‐resistant bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 61, 557–568 (2021).

Lalthanpuii, P., Lalchhandama, K. Technology Analysis of chemical constituents and antiparasitic activities of the extracts of imperata cylindrica. Res. J. Pharm. 13, 653–658 (2020).

Younis, S. S., Abou-El-Naga, I. F. & Radwan, K. H. Molluscicidal effect of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica on biomphalaria Alexandrina snails and schistosoma mansoni cercariae. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 13, 35–44 (2023).

Choi, K. M., Gang, J. & Yun, J. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii RH strain activity of herbal extracts used in traditional medicine. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 32, 360–362 (2008).

Santos, I. P. et al. Antibacterial activity of endophytic fungi from leaves of indigofera suffruticosa miller (Fabaceae). Front. Microbiol. 6, 350 (2015).

Gamea, G. A. et al. Direct and indirect antiparasitic effects of chloroquine against the virulent RH strain of Toxoplasma gondii: an experimental study. Acta Trop. 232, 106508 (2022).

Hezema, N. N., Eltarahony, M. M. & Abdel Salam, S. A. Therapeutic and antioxidant potential of Bionanofactory ochrobactrum sp.-mediated magnetite and zerovalent iron nanoparticles against acute experimental toxoplasmosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011655 (2023).

Saad, A. E., Zoghroban, H. S., Ghanem, H. B., El-Guindy, D. M. & Younis, S. S. The effects of L-citrulline adjunctive treatment of Toxoplasma gondii RH strain infection in a mouse model. Acta Trop. 239, 106830 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Molecular mechanisms of the chemical constituents from anti-inflammatory and antioxidant active fractions of ganoderma neo-japonicum Imazeki. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 6, 100441 (2023).

Al-Kuraishy, H. M., Al-Gareeb, A. I., Elekhnawy, E. & Batiha, G. E. S. Dipyridamole and adenosinergic pathway in Covid-19: a juice or holy Grail. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 23, 140 (2022).

Al-Fakhrany, O. M. & Elekhnawy, E. Helicobacter pylori in the post-antibiotics era: from virulence factors to new drug targets and therapeutic agents. Arch. Microbiol. 205, 301 (2023).

Alomair, B. M. et al. Is sitagliptin effective for SARS-CoV-2 infection: false or true prophecy? Inflammopharmacology 30, 2411–2415 (2022).

Chen, W. Y. et al. Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of fungal Immunomodulatory protein involving microglial Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3678 (2018).

Borquaye, L. S. et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of extracts of reissantia indica, Cissus cornifolia and Grosseria vignei. Cogent Biol. 6, 1785755 (2020).

FarahatAllam, A., Shehab, A. Y., Mogahed, N. M. F. H., Farag, H. F. & Elsayed, Y. Abd El-Latif, N.F. Effect of nitazoxanide and spiramycin metronidazole combination in acute experimental toxoplasmosis. Heliyon. 6 (2020).

Ganesan, T., Subban, M., Christopher Leslee, D. B., Kuppannan, S. B. & Seedevi, P. Structural characterization of n-hexadecanoic acid from the leaves of Ipomoea Eriocarpa and its antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14, 14547–14558 (2024).

Sajayan, A., Ravindran, A., Selvin, J., Ragothaman, P. & Seghal Kiran, G. An antimicrobial metabolite n-hexadecenoic acid from marine sponge-associated bacteria Bacillus subtilis effectively inhibited biofilm forming multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Biofouling 39, 502–515 (2023).

Oulahal, N. & Degraeve, P. Phenolic-rich plant extracts with antimicrobial activity: an alternative to food preservatives and biocides? Front. Microbiol. 12, 753518 (2022).

Takó, M. et al. Plant phenolics and phenolic-enriched extracts as antimicrobial agents against food-contaminating microorganisms. Antioxidants. 9, 165 (2020).

Bouarab-Chibane, L. et al. Antibacterial properties of polyphenols: characterization and QSAR (Quantitative structure–activity relationship) models. Front. Microbiol. 10, 829 (2019).

Abdelraheem, W. M., Abdelkader, A. E., Mohamed, E. S. & Mohammed, M. Detection of biofilm formation and assessment of biofilm genes expression in different Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Meta Gene. 23, 100646 (2020).

Yang, D. et al. Paeonol attenuates quorum-sensing regulated virulence and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 12, 692474 (2021).

Tuon, F. F., Dantas, L. R. & Suss, P. H. Tasca Ribeiro, V.S. Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm: a review. Pathogens. 11, 300 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. Maha Hammady Hemdan for her support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, O.M.A.-F.; Investigation, E.E., N.S., and L.A.S.; Methodology, E.E., N.A.E.-S., S.Y., H.A.R., E.A.E., L.A.S., and O.M.A.-F.; Resources, E.M. and R.A.; Software, E.M., E.E., R.A. and N.S.; Writing-original draft, R.A., S.Y., H.A.R., E.A.E., and O.M.A.-F.; Writing-review and editing, E.E. and E.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was performed in line with the guidelines of the ethics committee of the Faculty of medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt (approval number 0306733). The authors declare that they have adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elekhnawy, E., Moglad, E., Sirag, N. et al. Multifunctional bioactivity of eco-friendly Penicillium gladioli extract against Toxoplasma gondii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 15, 42297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23921-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23921-z