Abstract

This study employed a physical foaming method to prepare foam concrete with steel slag (SS) partially replacing cement. The compressive strength was tested at different SS replacement ratios (0–50%). Through SEM testing, combined with ImageJ image analysis and the box-counting method, the fractal dimension was calculated. The results indicated that the pore size distribution of the steel slag foam concrete (SSFC) approximately followed a lognormal distribution. With increasing SS replacement ratio, both the average pore size and fractal dimension first decreased and then increased, reaching minimum values at a 20% SS replacement ratio, where the pore structure was the most uniform, with fewer large pores and the smallest fractal dimension D. In contrast, the compressive strength initially increased and then decreased with higher SS content, also peaking at the 20% replacement ratio. The observed trend of compressive strength decreasing with increasing fractal dimension D suggests that a lower D value corresponds to a more uniform pore distribution, with pores predominantly concentrated in relatively smaller size ranges, thereby reducing the formation of large pores that are prone to causing failure. Based on the fractal characteristics of the pores, a quantitative model was established to describe the relationship between compressive strength, fractal dimension, and porosity. This model clearly demonstrates a negative correlation between strength and fractal dimension, and it showed a good fit (R2 > 0.99) when validated against experimental data. The research demonstrates that an appropriate amount of steel slag can effectively optimize the pore structure and enhance the mechanical properties of foam concrete, providing theoretical and engineering insights for the resource utilization of industrial solid waste.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Foamed concrete (FC) is a lightweight material that reduces density by incorporating foam generated from a foaming agent. It offers high strength, excellent thermal insulation, and soundproofing properties1,2,3. This makes it widely applicable in external wall insulation, structural components, backfilling projects, and bridge void filling4,5,6,7.The macroscopic mechanical properties of foamed concrete are closely related to its micro and meso-structural characteristics, and elucidating this relationship has drawn significant attention in both engineering and scientific fields8,9,10,11,12.

In recent years, with increasing demands for the sustainability of building materials, the application of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) and novel cementitious systems has garnered increasing attention. Although fly ash remains the most widely used modification component in cement-based composites traditionally, current research trends have gradually shifted toward ternary and even quaternary composite cementitious systems, with the incorporation of nanomaterials (e.g., nano-silica) to further enhance performance, such as improving fracture toughness and other mechanical behaviors. However, systematic studies on novel admixtures and multi-component composite cementitious materials—particularly those combining thermally activated cementitious materials and nano-modification technologies—remain relatively limited13,14.

Against this background, fractal theory provides a powerful tool for quantitatively characterizing the complex microstructure of materials and establishing correlations with macroscopic properties. The fractal dimension can effectively quantify the geometric disorder and scale-invariant features of porous materials and has been widely applied in studies on pore structure, damage evolution, and fracture behavior of concrete15,16.

Pioneering work by Carpinteri et al.17 demonstrated the effectiveness of fractal dimension in evaluating crack size randomness in brittle materials, revealing its capability to reflect intricate damage mechanisms during crack propagation. Zhang et al.18 further refined this approach by correlating fractal dimensions from CT images with macroscopic mechanical damage variables through an improved box-counting method, thereby elucidating the micro–macro relationship in concrete. Studies by Armandei et al.19 and Issa et al.20 established that fractal dimension effectively quantifies fracture surface roughness and its correlation with fiber content or aggregate gradation, where higher fractal dimensions correspond to enhanced fracture toughness. Zhou et al.21 and Lyu et al.22 extended fractal analysis to performance prediction by establishing relationships between fractal parameters and macroscopic properties, specifically addressing frost resistance and dynamic compressive strength, respectively. Notably, Li et al.23 achieved three-dimensional multiscale damage evolution tracking in fiber-reinforced concrete through X-ray computed tomography-based fractal dimension analysis. However, current research predominantly focuses on conventional concrete systems, with limited exploration of fractal dimension variations in solid waste-modified systems such as steel slag composites.

Although the aforementioned studies have established a foundation for the application of fractal theory in linking the microstructure and macroscopic properties of concrete, most current work remains focused on conventional cement-based systems. Research on the relationship among fractal dimension, pore structure, and compressive strength in solid waste-modified cementitious systems, such as steel slag concrete, is still relatively scarce. Particularly in foamed concrete—a highly porous material—the complexity of the pore structure and its interaction with solid waste additions have not been systematically elucidated in terms of their effects on fractal characteristics and the resulting mechanical behavior.

Steel slag (SS) is a significant byproduct produced in large quantities during the steel manufacturing process, exhibits high density, high strength, and potential cementitious activity24,25,26, making it highly promising for applications in construction materials. Utilizing SS in the preparation of foamed concrete not only alleviates environmental burdens and reduces production costs but also significantly enhances its compressive strength27,28,29. Bai et al.30 incorporated iron-rich SS and carbon fibers into foamed concrete to improve its overall performance. Their study revealed that the optimal addition of iron-rich SS was 15%, which increased the compressive strength of the foamed concrete by 18.59% compared to the control group. Additionally, the material exhibited excellent electromagnetic wave absorption and superior electromagnetic loss properties. Liao et al.31 conducted a study to examine the effects of incorporating ultrafine SS on the performance characteristics of foamed concrete. The findings indicated that as the composition of SS increased, both the compressive strength and fracture strength of SSFC initially rose before subsequently declining, while water absorption exhibited a consistent upward trend. Furthermore, the inclusion of SS powder significantly enhanced the long-term strength of SSFC. He et al.32 studied the influence of SS powder with varying specific surface areas on the properties of foamed concrete. Through strength tests, XRD, and SEM analyses, they found that the compressive strength of foamed concrete initially increased and then decreased with the increase in the specific surface area of the SS powder. Zhou et al.33 explored the potential of fully replacing lime with steel slag (SS) as a calcium source, combined with deactivated ZSM-5, for producing autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC). The study focused on how the Ca/Si ratio affected key properties such as foaming performance, bulk density, mechanical strength, mineral content, pore distribution, and microstructure. Results revealed that increasing the Ca/Si ratio enhanced the foaming effect in the early stages. An optimal Ca/Si ratio of 0.92 resulted in AAC that satisfied the national standards for both compressive strength and bulk density, meeting the specifications for grade A2.5 and B05. Piro et al.34 investigated the effects of partially replacing cement and fine aggregates with SS on the compressive strength and resistivity of concrete with different mix proportions. Their results indicated that SS-enhanced M25 concrete exhibited 2.27% lower CS compared to non-SS M25 concrete after 28 days of curing. Conversely, SS-modified M35 concrete showed a 6.74% higher CS than its unmodified counterpart. Yuan et al.35 conducted grouped experiments on pavement concrete using SS powder as a partial replacement for cement, varying water-cement ratios, SS parameters, and coarse aggregate particle sizes. The findings showed that the incorporation of SS improved concrete workability but attenuated compressive strength. The concrete exhibits optimal performance when the SS content is 35%. In coarse aggregates, utilizing SS as a sand substitute effectively reduced cost.

However, existing research has predominantly focused on the influence of steel slag on the macroscopic properties of foamed concrete, while systematic investigations into the evolution of microstructural (particularly pore structure) fractal characteristics after its incorporation and how such fractal behavior affects compressive strength remain scarce. Furthermore, recent international studies have shown a growing tendency to employ non-contact measurement techniques (such as digital image correlation, DIC) to examine the effects of multi-component admixtures and nano-modification on crack development in concrete36,37, and to analyze fracture mechanisms from the perspective of interfacial microstructure38. These emerging methodologies also provide valuable references for the present study.

Against this backdrop, this paper takes steel slag foamed concrete as the research object. Through experimental testing of the compressive strength and SEM microstructures at varying steel slag incorporation levels, image processing techniques were employed to statistically analyze pore distribution, and the box-counting method was applied to calculate the corresponding fractal dimensions. This study systematically investigates the influence of steel slag content on the fractal dimension and establishes a quantitative relationship among fractal dimension, pore structure, and compressive strength. The aim is to reveal, from a microstructural perspective, the mechanism by which steel slag influences the macroscopic properties of foamed concrete, thereby providing a theoretical basis and design guidance for the high-value utilization of solid waste in functional building materials.

Materials and testing methods

Experimental materials

The materials utilized in this experiment comprised Conch-brand P·O 42.5 grade Portland cement sourced from Anhui, SS obtained from Ma’anshan Iron & Steel Company in Anhui, tap water, and foaming agent.

Cement

The Portland cement used in this study was Conch-brand P·O 42.5 grade, sourced from Anhui. This type of cement is known for its low cost, rapid setting and hardening, as well as its superior durability and abrasion resistance. The chemical composition and performance indicators are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Its physical properties are summarized in Table 3.

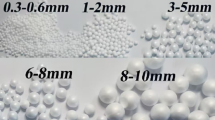

Steel slag

The SS employed in this investigation was sourced from Ma’anshan Iron & Steel Company in Ma’anshan City, Anhui Province, and had been weathered for over two years. The SS was sieved through a 1.18 mm mesh, and the resulting material used in the experiments is shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The chemical composition and physical properties of the steel slag are summarized in Tables 1 and 3, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, the chemical composition of the steel slag is similar to that of cement. The major oxides responsible for paste hardening—CaO, SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and Fe₂O₃—collectively account for 91.25% of the steel slag and 91.44% of the cement. The steel slag used in this study is highly alkaline, with a basicity value (R = CaO/SiO₂) of 4.1, which exceeds the threshold of 2.5 for classification as high-alkalinity slag. According to existing literature, the reactivity of steel slag is positively correlated with its basicity, indicating that the slag used in this study possesses relatively high reactivity.

The free lime (f-CaO) content was determined to be 2.7% using the sucrose-EDTA complexometric titration method in accordance with the Chinese standard YB/T 4328-2012, meeting the specified requirements. Furthermore, boiling and autoclave tests conducted on steel slag-cement paste following the Chinese standard GB/T 24763-2009 demonstrated an expansion rate of less than 7.8%, which is below the limit stipulated in the standard. These results confirm that the long-term weathered steel slag exhibits excellent volume stability. Therefore, this study utilized steel slag as a cementitious material to partially replace cement, thereby reducing overall cement consumption.

Foaming agent

The foaming agent creates fine pores in the concrete by trapping air bubbles within the slurry, reducing its overall weight. The foaming agent used in this test is a blowing agent produced by a company in Wuhan. The blowing agent is a transparent liquid with pH value of 8.3. The main chemical component is sodium dodecyl sulfate. Its foaming ratio is 40. Its performance meets the specification requirements.

Preparation of SSFC

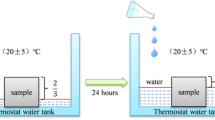

(1) Dry Mixing Phase: According to the mix proportion, cement and steel slag were weighed and initially dry-mixed at a low speed (approximately 300 rpm) for 60 s, followed by high-speed mixing (approximately 600 rpm) for an additional 30 s. (2) Liquid Phase Addition: Pre-measured water was added and mixed at low speed for 60 s. Then, pre-generated foam—produced by diluting the foaming agent (foaming agent-to-water ratio = 1:30)—was slowly incorporated into the slurry. Alternatively, preformed foam was directly pumped into the mixture. (3) Foam Parameters: Foam generator model: HW-3 high-speed foam generator; Foaming pressure: 0.6 MPa; Foam production rate: 1000 mL/min. (4) Mixing and Casting: After foam addition, the mixture was gently blended at low speed for 20–30 s. This process was repeated 3–4 times until homogeneity was achieved. The mixture was cast into molds coated with a release agent and lightly vibrated to remove large air bubbles (vibration table frequency: approximately 50 Hz; vibration duration: 3–5 s per mold). (5) Density Control: During preparation, the density of the slurry was monitored by weighing a 1 L sample. If the measured density deviated by more than ± 2% from the target value (600 kg/m3), the foam volume was empirically adjusted until the target density was met. (6) Specimen Preparation and Curing: At least six specimens were prepared for each group (three for compressive strength testing and three as backups or for repeat tests). The specimens measured 100 × 100 × 100 mm. They were demolded after 24 h and cured in a standard curing room (20 ± 2 °C, relative humidity ≥ 95%) until 7 days of age. The sample preparation process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

In the experiment, the dry density of the bentonite-steel slag foam concrete specimen was designed to be 600 kg/m3, and the steel slag was designed to replace cement with 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% and 50%, that is, the mass ratio of steel slag to cement was 0:100, 10:90, 20:80 , 30:70, 40:60, and 50:50 respectively. The water consumption in the test was controlled by water-to-binder ratio of 0.45.

Compressive strength test

The unconfined compressive strength test for SSFC was conducted according to the standard (JG/T 266-2011). The compressive strength tests were carried out using a universal testing machine. The test was performed under displacement control, with a loading rate of 1.0 mm/min. During the experiment, the axial load and displacement were recorded using a computer.

SEM analysis

Samples for SEM analysis were taken from the natural fracture surfaces of specimens after the compressive strength tests. These samples were placed in anhydrous ethanol to terminate the hydration reaction, dried, and subjected to gold coating. The micro-structural morphology of SSFC samples was analyzed using a JEM-6510 scanning electron microscope (SEM). All SEM images were acquired using a JEM-6510 microscope at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a magnification of 27 × . The images were saved in lossless TIFF format. For each specimen, at least three representative areas were randomly selected for imaging, resulting in a total of more than 15 images for statistical analysis.

Experimental results

Microstructure and fractal dimension of SSFC

Figure 4 shows the SEM images of FC with varying SS proportions. It is evident that the microstructure of SSFC undergoes significant changes with increasing SS proportion. As the SS proportion increases, the structure initially becomes denser. For instance, in concrete without SS, the surface grooves are relatively large. However, after incorporating 10% and 20% SS, the groove sizes gradually decrease, and the pore structure becomes more uniform. When the SS proportion is further increased, structural degradation becomes evident. The surface groove sizes gradually enlarge, and distinct cracks appear in concretes with 40% and 50% SS, indicating a looser pore structure. This phenomenon can be explained as follows: during the preparation of foamed concrete, adding a certain amount of SS increases the fluidity of the slurry, which facilitates the bonding between the foam and slurry. This bonding reduces the likelihood of foam collapse, resulting in a large number of small-diameter pores in the concrete. However, when the SS proportion exceeds 20%, the slurry becomes too fluid, causing the settling of SS, a reduction in viscosity, and a decrease in friction between the slurry and foam surfaces. Consequently, the upper-layer slurry becomes more fluid, causing the foam to grow larger as it rises, and in some cases, to collapse. This process forms numerous interconnected pores or even large cracks in the concrete.

All SEM images were processed using ImageJ for binarization: the original TIFF images were uniformly converted to 8-bit grayscale. The binarization threshold was automatically determined using an iterative algorithm, which identifies the optimal segmentation threshold by maximizing the inter-class variance in the grayscale histogram, thereby effectively avoiding subjective bias from manual selection.

A geometric sequence with a base of 2 was used for the box sizes (ε), i.e., ε = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, …, ε_max. This series covers a wide range of scales from single pixels to characteristic feature sizes in the images, meeting the multi-scale requirements of fractal analysis. When ε approaches zero, the fractal dimension calculation formula using the box-counting dimension method is expressed as:

From the above equation, it follows that smaller ε values yield more accurate fractal dimensions. However, ε cannot be infinitesimally small—its minimum value corresponds to the length of a single pixel. This is because the pixel size δ is defined as the length of the image L divided by the number of pixels in a column. The side length a of the square box is then a = εδ, where ε = 1,2,4, …,2i. By fitting the relationship between different ε values and their corresponding N(ε), and using the least squares method, the following equation is obtained:

Here, D1 represents the fractal dimension in the two-dimensional plane, equaling the absolute value of the regression slope due to its inherent negative trend.

It should be noted that the fractal dimension calculated in this study is derived from two-dimensional SEM images. While this approach is widely adopted for its practicality and effectiveness in characterizing planar pore complexity, the pore structure of foamed concrete is inherently three-dimensional and exhibits multi-scale characteristics. The conversion from 2 to 3D fractal dimension using the relation D = D1 + 1 is based on the assumption of isotropic and non-stratified pore distribution, which may not fully capture the spatial heterogeneity of the pore network. Future studies employing non-destructive 3D imaging techniques such as X-ray micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the fractal behavior in three dimensions and further validate the correlations established in this work.

Not all box sizes were included in the linear regression for the fractal dimension calculation. The minimum box size (εmin) was set to 4 pixels to exclude the influence of pixel-level noise. The maximum box size (εmax) was set to less than one-fourth of the shorter side length of the image to avoid statistical uncertainty due to an insufficient number of boxes. The final valid regression interval was determined based on the following two criteria: (a) a segment of the double logarithmic curve exhibiting good linearity (initially identified by visual inspection); and (b) a coefficient of determination (R2) greater than 0.995 for the linear regression within this segment. Only when the goodness-of-fit of the linear regression met this criterion was the slope considered to represent a reliable fractal dimension value D₁, indicating significant fractal characteristics within the corresponding scale range.

The fractal dimension for each sample was reported as the average value calculated from at least three different fields of view in the SEM images. The relationship between steel slag replacement ratios and corresponding fractal dimensions is summarized in Table 4, with representative test results displayed in Fig. 5.

The fractal dimension calculated using the box-counting method, represents the value in a two-dimensional plane. The three-dimensional fractal dimension (D) is 1 greater than the two-dimensional fractal dimension (D1), i.e., D = D1 + 139. This approximation remains reasonable provided that the following conditions are met40,41: 1) the material structure exhibits no significant stratification or strong anisotropy in three dimensions; 2) the selected two-dimensional cross-section is representative and reflects the scale-invariant characteristics of the overall pore structure; 3) the fractal properties observed in the two-dimensional section are consistent across multiple randomly selected sections. In this study, the stability of D₁ across samples was verified through two-dimensional fractal analysis performed on at least three specimens for each mix proportion. Hence, within the constraints of the experimental conditions, it is feasible to adopt the relation D = D₁ + 1 as a reasonable estimation.

As shown in the table, the fractal dimension of FC increased after the incorporation of SS. This is attributed to the rough and uneven surface of the SS, which has a relatively high fractal dimension. The fractal dimension of SSFC reduces initially and then augments with the SS proportion, reaching its minimum at 20% proportion. To better characterize the influence of the SS proportion on the fractal dimension, the ImageJ tool was used to label the pores and analyze the pore diameter characteristics of the specimens. This analysis served to represent the changes in micro-structural patterns and the mechanisms behind the variation in fractal dimensions. The pore size characteristics of SSFC with varying SS proportions are summarized in Table 5. The pore size distribution for each specimen was determined by analyzing no fewer than 600 pores. A lognormal distribution model was employed to fit the data, and the goodness-of-fit was confirmed by coefficients of determination (R2) exceeding 0.96 for all cases, indicating a good fit. The standard errors (SE) of the fitting parameters μ and σ were computed via nonlinear regression. All parameter estimates were found to be statistically significant based on t-tests (p < 0.05). Therefore, the probability density \(f_{d} (d,\mu ,\sigma )\) function was used to describe the distribution.

where d is the pore diameter (μm), μ is the mean of the logarithm of d and σ is the standard deviation of the logarithm of d.

The pore size distribution characteristics of each sample were determined by analyzing the range and frequency of pore diameters, as shown in Fig. 6. As seen in Fig. 6, the pore size distribution of SSFC adheres to a log-normal distribution, with the pore diameters concentrated in the range of 160–250 μm. Table 5 presents the results calculated based on the probability density function. The larger the log mean value μ, the greater the corresponding pore diameter. The log standard deviation σ indicates the degree of dispersion in the pore size distribution; a higher σ value corresponds to a broader range of pore sizes. The analysis revealed a close relationship between the fractal dimension and the pore size distribution. As the SS proportion rises, the dispersion of the pore size distribution first decreases and then increases, leading to a decrease and then an increase in the fractal dimension. At 20% SS proportion, the dispersion of the pore size distribution is minimal, the pore structure is most compact, and the fractal dimension is smallest. It is also observed that a smaller fractal dimension corresponds to a smaller average pore size. This is because, at constant porosity, a more uniform pore distribution results in a higher number of smaller pores and a lower proportion of larger pores, thus reducing the average pore size. In contrast, a larger fractal dimension indicates a more uneven pore distribution, with higher dispersion. Smaller pores merge to form larger ones, increasing the proportion of larger pores and thus raising the average pore size.

Fractal dimension and its correlation with material strength

Figure 7 illustrates the compressive strength of FC with different levels of SS proportion. The results indicate that adding SS improves the compressive strength of FC. As the SS proportion rises, the compressive strength of SSFC initially increases but later decreases. The peak compressive strength of SSFC occurs when the SS proportion reaches 20%. One-way analysis of variance showed that the strength of the 20% steel slag addition group was significantly different from that of the other groups (p < 0.05). At this point, the compressive strength of the SSFC reached 1.8 ± 0.073 MPa, which meets the performance specifications for foamed concrete with a target density of approximately 600 kg/m3 as stipulated in the Chinese industry standard JG/T 266-2011.This phenomenon corresponds with the observed alteration in pore structure, which becomes more compact at first and then more porous as the SS proportion increases.

Considering the analysis above, it can be concluded that the compressive strength of SS foamed concrete (SSFC) is inversely related to its fractal dimension, with a decrease in fractal dimension corresponding to an increase in compressive strength. This indicates that a narrower range of pore size distribution leads to a more uniform pore structure, and under the same porosity, smaller average pore size results in higher compressive strength. To gain a deeper understanding of the connection between foamed concrete strength and its fractal dimension, it is essential to establish a quantitative relationship between them. According to literature42, there is a connection between the porosity of FC and its fractal dimension:

In the equation, φ denotes the porosity of FC, fc is a proportional constant, dc represents the aperture diameter, di denotes the initial aperture diameter, and D stands for the fractal dimension.

The compressive strength of foamed concrete (FC) is closely related to its skeleton fractal dimension. Unlike the mass fractal dimension, the skeleton fractal dimension primarily describes the amount of intermolecular forces between pores, and there is a functional connection between the two. This connection can be described by the following equation39:

In the equation, N denotes the quantity of binding links, X represents the fractal dimension of skeleton. The skeleton fractal dimension X is 1 unit smaller than the mass fractal dimension D, i.e., X = D − 1 = D1, where D1 is the two-dimensional fractal dimension.

The compressive strength of foamed concrete (FC) results from the cumulative bonding forces within the material. Its fracture strength, on the other hand, is determined by both the quantity of interparticle binding links and the attractive forces between the particles. Consequently, the compressive strength of FC can be expressed by the following equation:

Using Eq. (4) and (6), the expression for the compressive strength of FC in relation to porosity (φ) can be derived as follows:

In the equation, (2X − 3D + 3)/[3(D − 3)] represents the parameter b. From X = D − 1, the compressive strength can be derived as a function of the fractal dimension D:

where σf represents the compressive strength of the foamed concrete, σf0 denotes the compressive strength of the dense (non-porous) foamed concrete, φ is the porosity of the foamed concrete, and D is the three-dimensional fractal dimension.

To investigate the relationship between the compressive strength and porosity of the SSFC, the compressive strength of SSFC with 20% steel slag replacement was tested at different porosity levels: 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7. The compressive strength of the dense foamed concrete (with zero intentional porosity) at 20% steel slag replacement was experimentally determined to be 26.9 MPa. Using the previously measured fractal dimension value of D = 2.8, the relationship between compressive strength and porosity was derived as follows: \(\sigma_{f} = 26.9(1 - \varphi )^{3}\) with a correlation coefficient of 0.9958. Figure 8 compares the experimentally measured compressive strengths with the fitted curve, demonstrating a good agreement. Furthermore, the proposed relationship was compared with data from Reference39, as shown in Fig. 9. The close consistency between the two further validates the feasibility and general applicability of the derived relationship between compressive strength and porosity.

Using Eq. (8), the influence of the fractal dimension on compressive strength was also illustrated, as shown in Fig. 10. Figure 10 clearly demonstrates that as the fractal dimension increases, the compressive strength of foamed concrete notably declines, consistent with the trend observed in this study—where SS proportion increases, strength initially increases and then decreases, while fractal dimension decreases initially and then increases. This indicates that the fractal dimension has a significant influence on the strength of foamed concrete. The physical relationship between the skeletal fractal dimension (X) and the mass fractal dimension (D), expressed as X = D − 1, can be interpreted as a dimensional reduction from a ‘space-filling’ structure to a ‘load-bearing’ network41. A higher fractal dimension D indicates a more complex and heterogeneous pore structure, which results in a more tortuous and fragile solid skeleton (higher X). Such a complex skeletal network leads to inefficient load transfer and intensified stress concentrations, ultimately reducing the macroscopic compressive strength17,39.

This intuitive mechanism is consistent with our experimental results: the sample with the most uniform pore structure (20% SS replacement) exhibited the lowest D value and consequently the highest strength, strongly validating the inverse correlation between compressive strength and fractal dimension.

Conclusion

This study aims to enhance the understanding of micro-structural changes in foamed concrete with the incorporation of SS and to establish the relationship between fractal dimension and macroscopic mechanical properties. Through macro- and micro-testing, combined with image analysis software, the mechanical properties, pore structure, and fractal dimension were quantified, revealing their interrelationships. The main findings are as follows:

-

(1)

The incorporation of SS increased the fractal dimension of foamed concrete, with the fractal dimension initially decreasing and then increasing as the SS proportion increases; the SSFC pore size distribution approximated a lognormal distribution. Adding an appropriate amount of SS improves the uniformity of SSFC’s micro-structure. As SS proportion increases, SSFC’s average pore size and pore size dispersion δ first decrease and then increase, showing a strong correlation between fractal dimension and pore size dispersion. Smaller pore size dispersion leads to a more uniform pore structure, and thus a lower fractal dimension.

-

(2)

The compressive strength of SS foamed concrete exhibits an opposite trend to fractal dimension with increasing SS proportion. As SS proportion increases, SSFC’s compressive strength initially rises and then declines, peaking at a SS proportion of 20%. This is because a lower fractal dimension represents smaller pore size spans, leading to a more uniform pore structure, which results in smaller average pores and denser matrix, thereby enhancing concrete strength.

-

(3)

A relationship model between foamed concrete compressive strength and its fractal dimension was established. The accuracy of this formula was validated by comparing measured compressive strength values at different porosity levels. The resulting diagram illustrates the impact of fractal dimension on strength, showing a clear decrease in SSFC strength with increasing fractal dimension. Thus, fractal dimension significantly influences the strength of foamed concrete. Incorporating an appropriate amount of SS ensures a more uniform pore structure, reduces the fractal dimension, and subsequently increases its compressive strength.

Further discussion

This study only explored the performance of steel slag foam concrete (SSFC) under conditions of a dry density of 600 kg/m3 and a water-binder ratio of 0.45. It did not investigate the influence of different densities and water-binder ratios, nor did it conduct durability tests. Although the established theoretical model fits well with the experimental data (R2 > 0.99), its universality still needs to be further verified through larger sample data.

In addition to compressive strength, the fractal dimension may also serve as a potential indicator for predicting the durability of steel slag foamed concrete (SSFC). A more uniform pore structure, reflected by a lower fractal dimension, is likely to enhance impermeability and resistance to aggressive ion penetration, thereby improving durability properties such as freeze–thaw resistance and sulfate attack resistance. For instance, a lower fractal dimension implies fewer interconnected large pores, which are critical pathways for moisture and chloride ingress. Future research should systematically investigate the relationship between fractal dimension and key durability indicators (e.g., chloride diffusion coefficient, freeze–thaw cycle performance) to establish a comprehensive microstructure–property–durability framework for SSFC.

Subsequent studies can combine X-CT technology to expand the mix proportion parameters and systematically carry out durability tests, in order to establish a complete evaluation system of microstructure—mechanical properties—durability. The refined pore structure formed under the substitution of 20% steel slag is expected to enhance the impermeability and support the application of SSFC in external wall insulation and backfilling projects.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dhasindrakrishna, K., Pasupathy, K., Ramakrishnan, S. & Sanjayan, J. Rheology and elevated temperature performance of geopolymer foam concrete with varying PVA fibre dosage. Mater. Lett. 328, 133122 (2022).

Brelak, S. & Dachowski, R. Effect of autoclaved aerated concrete modification with high-impact polystyrene on sound insulation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 245, 022089 (2017).

Raj, A., Sathyan, D. & Mini, K. M. Physical and functional characteristics of foam concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 221, 787–799 (2019).

Amran, Y. H. M., Farzadnia, N. & Abang Ali, A. A. Properties and applications of foamed concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 990–1005 (2015).

Bhosale, A., Zade, N. P., Sarkar, P. & Davis, R. Mechanical and physical properties of cellular lightweight concrete block masonry. Constr. Build. Mater. 248, 118621 (2020).

Krämer, C., Schauerte, M., Kowald, T. L. & Trettin, R. H. F. Three-phase-foams for foam concrete application. Mater. Charact. 102, 173–179 (2015).

Jin, Y., Wang, X., Huang, W., Li, X. & Ma, Q. Mechanical and durability properties of hybrid natural fibre reinforced roadbed foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134008 (2023).

Ioannidou, K. et al. Mesoscale texture of cement hydrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 2029–2034 (2016).

Tikalsky, P. J., Pospisil, J. & MacDonald, W. A method for assessment of the freeze–thaw resistance of preformed foam cellular concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 34, 889–893 (2004).

Ma, H. et al. Micro/meso scales characterization of alkali-activated fly ash-slag concrete under sustained high-temperatures with X-CT, MIP, and SEM tests. Mater. Today Sustain. 28, 101036 (2024).

Zhao, D. et al. Study on the correlation between pore structure characterization and early mechanical properties of foamed concrete based on X-CT. Constr. Build. Mater. 450, 138603 (2024).

Ghahremani, G., Bagheri, A. & Zanganeh, H. The effect of size and shape of pores on the prediction model of compressive strength of foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 371, 130720 (2023).

Xi, X. et al. Mechanical properties and hydration mechanism of nano-silica modified alkali-activated thermally activated recycled cement. J. Build. Eng. 98, 110998 (2024).

Wang, L., Zhang, P., Golewski, G. & Guan, J. Editorial: Fabrication and properties of concrete containing industrial waste. Front. Mater. 10, 1169715 (2023).

Mandelbrot, B. B. The fractal geometry of nature (Echo Point Books & Media, 2022).

Campbell, P. & Abhyankar, S. Fractals, form, chance and dimension: benoit B. Mandelbrot. Math. Intell. 1, 35–37 (1978).

Carpinteri, A. & Yang, G. P. Fractal dimension evolution of microcrack net in disordered materials. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 25, 73–81 (1996).

Zhang, L., Dang, F., Ding, W. & Zhu, L. Quantitative study of meso-damage process on concrete by CT technology and improved differential box counting method. Measurement 160, 107832 (2020).

Armandei, M. & de Souza Sanchez Filho, E. Correlation between fracture roughness and material strength parameters in SFRCs using 2D image analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 140, 82–90 (2017).

Issa, M. A., Issa, M. A., Islam, Md. S. & Chudnovsky, A. Fractal dimension––A measure of fracture roughness and toughness of concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 70, 125–137 (2003).

Zhou, S. et al. Study on the influence of fractal dimension and size effect of coarse aggregate on the frost resistance of hydraulic concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 431, 136526 (2024).

Lyu, Y. et al. Dynamic failure characteristics of high-strength concrete and high-strength rock based on fractal theory. Eng. Fract. Mech. 308, 110345 (2024).

Li, X., Ma, R., Bao, Y., Sun, H. & Liu, R. Three-Dimensional Assessment of Damage Evolution for Fiber-Reinforced Recycled Powder Concrete Based on X-Ray Computed Tomography and Fractal Theory (2024). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4796970

Liu, S. & Li, L. Influence of fineness on the cementitious properties of steel slag. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 117, 629–634 (2014).

Devi, V. S. & Gnanavel, B. K. Properties of concrete manufactured using steel slag. Procedia Eng. 97, 95–104 (2014).

Jiang, Y., Ling, T.-C., Shi, C. & Pan, S.-Y. Characteristics of steel slags and their use in cement and concrete—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 136, 187–197 (2018).

Baalamurugan, J., Kumar, V. G., Padmapriya, R. & Raja, V. K. B. Recent applications of steel slag in construction industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 2865–2896 (2023).

Li, Y., Liu, F., Yu, F. & Du, T. A review of the application of steel slag in concrete. Structures 63, 106352 (2024).

Wu, P. et al. The harmless and value-added utilization of red mud: Recovering iron from red mud by pyrometallurgy and preparing cementitious materials with its tailings. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 132, 50–65 (2024).

Bai, Y., Chen, Y. & Xie, Y. Electromagnetic wave absorption value of iron-rich steel slag for application in foam concrete. Mater. Lett. 371, 136923 (2024).

Liao, Y., Jiang, G., Wang, K., Al Qunaynah, S. & Yuan, W. Effect of steel slag on the hydration and strength development of calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 265, 120301 (2020).

He, D. L. et al. Influence of steel slag powder with different specific surface area on the properties of foam concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 575, 95–99 (2012).

Zhou, L. et al. Effect of Ca/Si ratio on the properties of steel slag and deactivated ZSM-5 autoclaved aerated concrete. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 100, 100853 (2023).

Piro, N., Salih Mohammed, A. & Hamad, S. M. Slump monitoring and electrical resistivity comparison in concrete modified with steel slag as fine aggregate replacement. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 9, 2 (2024).

Yuan, B., Zhao, D., Lei, J. & Song, S. Preparation and performance testing of steel slag concrete from steel solid waste. Buildings 14, 2437 (2024).

Golewski, G. L. Investigating the effect of using three pozzolans (including the nanoadditive) in combination on the formation and development of cracks in concretes using non-contact measurement method. Adv. Nano Res. 16, 217–229 (2024).

Golewski, G. L. Using digital image correlation to evaluate fracture toughness and crack propagation in the mode I testing of concretes involving fly ash and synthetic nano-SiO2. Mater. Res. Express 11, 95504 (2024).

Golewski, G. L. et al. Experimental evaluation of mode II fracture and microstructure of matrix-aggregate bond of concrete with crushed limestone. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 23, e05183 (2025).

Chen, Y. & Xu, Y. F. Compressive strength of fractal-textured foamed concrete. Fractals 27, 1940003 (2019).

Gouyet, J.-F. & Bug, A. L. R. Physics and fractal structures. Am. J. Phys. 65, 676–677 (1997).

Krohn, C. E. & Thompson, A. H. Fractal sandstone pores: Automated measurements using scanning-electron-microscope images. Phys. Rev. B 33, 6366–6374 (1986).

Xu, Y., Jiang, H., Chu, F. & Liu, C. Fractal model for surface erosion of cohesive sediments. Fractals 22, 1440006 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the support provided by the following funding sources.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province of China (Grant No. 2208085MD98) and the Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Anhui Province of China (Grant No. 2022AH052430). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Guosheng Xiang:** Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Funding acquisition. **Qianqian Chen:** Investigation; Writing—review & editing. **Feiyang Shao:** Investigation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. **Zhe Huang:** Supervision; Review. **Ruiqing Xu:** Supervision; Review. **Ming Zhang:** Supervision; Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Shao, F., Xiang, G. et al. Fractal dimension of steel slag foamed concrete and its connection with compressive strength. Sci Rep 15, 40164 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23934-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23934-8