Abstract

This paper addresses three critical challenges in urban traffic digital twin systems: (1) achieving high-fidelity multi-source data fusion, (2) overcoming computational bottlenecks in large-scale real-time traffic simulation, and (3) enabling intuitive dynamic interaction for enhanced decision-making. To this end, we propose and implement a novel Unity-based digital twin system with a three-layer architecture. This architecture comprises: (1) a System Construction Layer integrating Google Maps, BlenderGIS, and CityEngine via Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) fusion to generate sub-meter accuracy 3D models (Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) ≤ 0.15m) with parametric Computer Generated Architecture (CGA) road editing; (2) a Data Acquisition Layer synchronizing Amap Application Programming Interface (API) traffic flow and OpenWeatherMap weather data to drive real-time environmental responses (e.g., rain particles = API intensity × 80); and (3) a Concept Generation Layer implementing an optimized 3-Degrees of Freedom (3-DoF) vehicle dynamics model with linear tire stiffness. Key innovations include Graphics Processing Unit (GPU)-accelerated collision detection (Unity Physics), an adaptive Level of Detail (LOD) strategy for 1,500-vehicle concurrent simulation at 60 Frames Per Second (FPS), and closed-loop decision feedback. Validated on an i7-13700H/RTX 4060 platform, the system reduces Central Processing Unit (CPU)/GPU utilization by 47%/48% versus nonlinear models while maintaining trajectory error < 0.23m (9.5%) in 80 km/h emergency scenarios. Comprehensive comparative experiments confirm its efficacy, providing crucial technical support for smart traffic management, autonomous driving testing, and policy pre-evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With accelerating urbanization and increasing complexity of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), there is a growing demand for highly dynamic and predictive traffic management solutions. Digital Twin (DT) technology provides a revolutionary paradigm for real-time monitoring, simulation, and optimized decision-making in urban traffic by constructing high-fidelity virtual replicas of physical transportation systems1. However, developing Digital Twin platforms for large-scale urban traffic scenarios that simultaneously achieve high accuracy and efficiency remains challenging, limiting their effectiveness in real-time decision support and hindering advancements in smart traffic management and autonomous driving testing2.

The development of robust and effective urban traffic Digital Twin systems is currently impeded by three critical bottlenecks:

1. Multi-source heterogeneous data fusion difficulties: Significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity and semantic discrepancies exist among geospatial information (GIS), real-time traffic flow, environmental perception data (e.g., cameras, radar), and static infrastructure models (Building Information Modeling, BIM). Current platforms struggle with precise alignment, causing deviations between the twin and the physical world3. For instance, the Huawei Cloud Digital Twin framework achieves only 89.7% data association accuracy in complex intersection scenarios (based on internal test reports), hindering fine-grained control and reliable decision-making.

2. Inefficient large-scale traffic flow simulation: Traditional high-fidelity vehicle dynamics models (e.g., multi-body dynamics models) suffer from high computational complexity, resulting in prohibitively long single-step simulation times that cannot meet real-time simulation demands for tens of thousands of concurrent vehicles4.

3. Inadequate visualization and interaction: Professional traffic simulation tools (e.g., SUMO, Vissim) lack strong three-dimensional (3D) rendering capabilities and immersive interaction mechanisms, limiting decision-making intuitiveness and the ability to effectively explore 'what-if’ scenarios5.

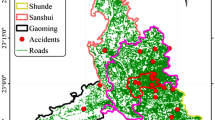

Addressing these critical challenges, this paper proposes and implements a novel, Unity-based high-fidelity urban traffic Digital Twin system. This system is specifically designed to provide crucial technical support for urban traffic management, autonomous vehicle testing, and policy pre-evaluation by establishing a high-fidelity, interactive 3D virtual training and simulation platform capable of real-time performance and dynamic interaction. Its core innovations include a Multi-layer Fusion Architecture and Sub-meter Accuracy Scene Construction. The System Construction Layer integrates Google Maps basemaps, BlenderGIS building models, and CityEngine road topology data to generate a three-dimensional (3D) urban model with terrain undulations at sub-meter accuracy (Fig. 1). It also integrates traffic signal systems, charging behavior simulation and other elements using Unity MARS and EasyRoads3D Pro plugins6. The Data Acquisition Layer simulates multi-source sensors via Unity Device Simulator, synchronizes real-time device data streams through IoT Connect, and incorporates third-party services like Amap Application Programming Interface (API) (road topology) and OpenWeatherMap (weather data) for dynamic data updates7. Finally, the Concept Generation Layer inputs feature, product, and scenario data into the Digital Twin system, constructing feature, product, and scenario modules for virtual scene design. This design undergoes iterative refinement through continuous training, providing feedback for data correction.

Related works

Research on digital twin

Research on Digital Twin (DT) spanned distinct phases. From 2010 to 2018, the concept originated and technologies began to emerge. The concept of Digital Twin was initially proposed by NASA for spacecraft health management, with its core being real-time monitoring and prediction of physical systems through dynamic virtual-physical mapping. After 2010, the technology began to permeate the transportation field. However, limited by data acquisition and computational capabilities, early research focused on offline simulation and localized mapping. Grieves proposed the "Mirrored Spaces Model"8, first linking the lifecycle of a physical entity with its virtual model. Yet, within the transportation domain, only static simulations of single facilities (e.g., intersections) were achievable, lacking dynamic interaction capabilities9. A team at the University of Texas developed a traffic flow prediction model based on floating car data, pioneering the incorporation of real-time GPS data into simulations. However, prediction latency reached the minute level, insufficient for real-time decision support10.

The period from 2018 to 2022 marked a phase of technology convergence and system architecture construction. With the commercialization of 5G and the maturation of edge computing, Digital Twin traffic systems evolved a three-layer "Perception-Transmission-Decision" architecture, achieving a leap from localized mapping to city-scale dynamic interaction. At the perception layer, Singapore’s Land Transport Authority deployed over 100,000 IoT sensors to build a city-scale twin, combining LSTM-Transformer hybrid models to achieve 15-minute traffic flow prediction (error < 8%) and reducing response time to 90 seconds9. The transmission layer relied on 5G edge computing to reduce end-to-end latency. The Tokyo Institute of Technology’s SMDT platform validated vehicle-edge-cloud communication latency ≤ 810.59ms, meeting the real-time control requirements for V2X11. At the decision layer, Liao Xiwen et al. proposed a hierarchical twin architecture. The upper road twin used Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Networks (DCRNN) to predict spatiotemporal traffic flow, while the lower vehicle twin used Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) to achieve collaborative path planning. This solution demonstrated a 22% improvement in traffic efficiency and a 37% reduction in congestion rate in SUMO simulations12.

Post-2023 represents a period of intelligent leapfrogging and cross-domain collaboration for Digital Twins, witnessing breakthroughs in high-fidelity dynamic models and simulation efficiency. In high-fidelity dynamic modeling, for extreme environment rendering, Waymo employed Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) to synthesize low-visibility and icy road scenarios, accumulating billions of kilometers in simulated mileage and reducing real-world testing cycles by 90%12.For physical constraint enhancement, neural rendering techniques (e.g., Block-NeRF) simulate rain and snow dynamics by synthesizing photorealistic low-visibility scenarios, enabling trajectory prediction under extreme weather with 95% accuracy after training on multi-condition datasets13.

In terms of simulation efficiency, breakthroughs came through NVIDIA’s dynamic Level of Detail (LOD) scheduling strategy enabling heterogeneous computing architectures. On an RTX 4060 platform, it achieved real-time simulation of thousands of vehicles at 30fps, improving computational efficiency by 25–50 times compared to traditional models12. Concurrently, models became more lightweight. Wang P. et al. replaced 7-degree-of-freedom (7-DoF) nonlinear models with a 3-DoF model (longitudinal-lateral-yaw), achieving a lateral error of only 0.15m in the double lane-change scenario14. Xuan Yuan Lab further enhanced this approach using AI for residual compensation on Wang P. et al.'s foundation, reducing the double lane-change scenario error from 0.15m to 0.05m15.

Research on virtual traffic scene modeling

Research on Virtual Traffic Scene Modeling dates back to 1992 when Goodchild M.F. proposed the concept of "Geographic Information Science" (GIScience), emphasizing that geographic information is not merely a technical tool but a science studying spatial data modeling, analysis, and decision-making. Subsequently, in 2002, Autodesk introduced Building Information Modeling (BIM), describing it as a technology for creating virtual 3D models of building engineering projects using digital techniques. This model contains comprehensive building engineering information. The National Institute of Building Sciences (USA) defined it as a "digital representation of physical and functional characteristics"16, covering the entire design, construction, and operation lifecycle, highlighting its information integration and visualization capabilities. Later, scholars recognized the potential for complementarity between GIS and BIM, fusing building and geographic data. Laat R.D. and Berlo L.V. developed the CityGML GeoBIM extension module, enabling the mapping of BIM attributes (e.g., component materials) to GIS spatial reference systems, supporting city-scale semantic integration. Zhu J. et al. proposed an open-source framework for converting IFC to Shapefile formats, addressing the semantic interoperability challenge between BIM’s micro-geometric information and GIS’s macro-spatial data17.

Within the Digital Twin domain, in 2024, Bao J. et al. proposed a Co-evolutionary Digital Twin (CoEDT) architecture18. It automatically fuses GIS elevation data with a BIM parametric component library to generate road models with terrain undulations. Modular lightweight packaging technology increased model reuse rates by 60% and reduced modeling costs by 42% in the Shenzhen Futian District hub project, solving the problem of distortion in reproducing complex urban terrain.

Beyond building and geographic data, CityEngine parametric road construction provides a method for Digital Twin road creation. Traditional Unity road modeling plugins cannot accurately read data from BIM. CityEngine, however, can associate BIM component attributes (e.g., material codes, floor heights) with GIS features, converting 2D surface data into 3D elements conforming to the terrain. This results in road models compliant with building and geographic data, with building footprint-to-terrain fitting errors below 0.2m19. While CityEngine models themselves are incompatible with the Unity engine’s material system, its Shader conversion plugin can automatically transform CGA materials into Unity Shader Graph, largely preserving texture mapping.

For weather systems, platforms like OpenWeatherMap are accessed via REST APIs to obtain precipitation intensity, visibility, and other data, driving dynamic scene responses. Singapore’s Land Transport Authority employs particle systems interacting with road colliders for rain and snow fluid effects to simulate dynamic water accumulation diffusion. Based on PM2.5 concentration and humidity data, scene fog density is dynamically adjusted to conform to atmospheric scattering physics.

From the static data proposed in 1992 to the Co-evolutionary Digital Twin (CoEDT) architecture in 2024, virtual traffic scene modeling is transitioning from “static reproduction” to "dynamic symbiosis." Through the deep coupling of the GIS-BIM-CityEngine technology chain, combined with high-precision building and geographic models, parametric road generation rules, and physically constrained weather systems, a comprehensive modeling paradigm encompassing "geographic base - building elements - road network - environmental response" has been established. This provides sub-meter accuracy virtual-physical mapping capabilities for smart transportation.

Research on vehicle dynamics models

Vehicle dynamics models describe the mapping relationship between a vehicle’s motion state (position, velocity, acceleration) and external inputs (steering input, road friction) through mathematical equations. Their essence is to build a physical rules engine for "input-system-output."

Degrees of Freedom (DoF) in vehicle dynamics refer to the number of independent variables required to describe the vehicle’s motion state, with each degree corresponding to an independent motion dimension (e.g., displacement, rotation). The choice of degrees of freedom directly impacts model accuracy and computational complexity. Traditional models typically possess 14 degrees of freedom. The theoretical foundation of vehicle dynamics models is the “Magic Formula” tire model proposed by Pacejka in 201220, which uses trigonometric function combinations to describe nonlinear tire forces. This became the core algorithm for commercial software like ADAMS/Car and CarSim, specializing in single-vehicle limit handling simulations.

For single-vehicle limit handling simulation, the Mercedes-AMG team proposed a 14-DoF model in an SAE paper specifically designed for drift control21. This model accurately predicts chaotic motion during drifting through multi-body dynamics coupling. Consequently, the AMG GT series developed "Drift Mode," becoming the first production vehicle with automated drifting capability, launched on the AMG SL 63 in 202321. Jung & Gerdes also employed dynamic tire force allocation to suppress loss of control behavior at high speeds22.

However, in multi-vehicle simulations for conventional scenarios, traditional models incurred a single-step computation time of 1.2ms (for the double lane-change scenario). Since the Unity engine requires 30fps (33ms/frame) to support thousands of concurrent vehicles, traditional models cannot meet real-time requirements22. Furthermore, high-fidelity tire models (e.g., MF-Tyre) require iterative solutions to nonlinear equation systems, resulting in high CPU load. Additionally, traditional models used in specialized software (CarSim) employ the ISO coordinate system (X forward, Y left), which is incompatible with software like Unity using a left-handed coordinate system (Z forward, Y up). Conversion errors introduce attitude angle deviations.

Recently, Zhang et al. demonstrated that a 3-DoF model (longitudinal/lateral/yaw) can cover 90% of conventional scenarios23. They used a linear lateral stiffness formulation, significantly improving computational efficiency. The previously mentioned Wang P. et al. also chose to reduce degrees of freedom for model lightweighting14. Their research confirmed a lateral error of 0.15m for this lightweight model in the double lane-change scenario. Building on Wang P. et al.'s work, Xuan Yuan Lab employed AI enhancement for residual compensation, reducing the double lane-change scenario error from 0.15m to 0.05m15. Tencent’s TAD Sim 2.0 platform proposed a road-condition-based LOD strategy: activating the 3-DoF model on dry roads and switching to high-fidelity mode on icy surfaces. By utilizing dynamic LOD scheduling with GPU acceleration, computational efficiency was improved24. This provides the foundational idea for the Unity-optimized 3-DoF model proposed later in this paper.

System architecture and implementation

Unity is a real-time 3D development platform, holding over 60% of the global market share (2023 Unity official report). It advocates for “democratized development” by providing a low-code visual toolchain, lowering the barrier to creation in fields such as VR/AR, digital twins (virtual replicas of physical systems), and gaming. Unity simultaneously supports high-performance simulation of complex systems. Its customizable rendering pipeline enables lightweight rendering by disabling non-essential effects (such as global illumination), alongside multi-platform compatibility. Therefore, this study utilizes the Unity engine for constructing the virtual simulation platform.

The overarching goal of the platform is to build a high-fidelity, interactive 3D virtual training ground. This is achieved through full-process digital twin technology to dynamically simulate and optimize complex urban systems.A core consideration in its design is the efficient management and integration of diverse data formats across layers, crucial for ensuring both data accuracy and real-time performance.The architecture employs a three-stage closed-loop design(Fig. 1):

-

1.System Construction Layer: Builds a sufficiently precise urban base using geographic data from Google Maps (using the City of London financial district as an example).

-

2.Data Acquisition Layer: Integrates diverse data (road, weather, vehicle information) into the UNITY3D engine for realistic environmental simulation.

-

3.Concept Generation Layer: Incorporates functional modules such as logistics route simulation and fleet management simulation based on actual needs. This layer allows control over generated traffic vehicle quantities and types.

System construction layer: sub-meter digital twin base construction

Within the system construction layer, city geographic data is first extracted from Google Maps using a Blender plugin. The City of London area was chosen due to its characteristics: ultra-compact size (2.6 km2), very low resident population (~10,000), and exceptionally high daytime commuting population (>480,000), making it suitable for virtual traffic scenario simulation.

BlenderGIS, an open-source geospatial data processing plugin specifically designed for Blender25, effectively bridges Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and 3D modeling. It supports the direct import, processing, and visualization of multi-source geospatial data within the Blender environment. In this study, BlenderGIS was used to acquire vector and raster data (terrain, buildings, roads, vegetation) for the City of London area from the OpenStreetMap (OSM) platform. This data was automatically converted into Blender mesh models(Fig. 2). Specifically, the plugin employs the Delaunay triangulation algorithm (a classical method for connecting point sets into non-overlapping triangular meshes) to transform Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data into high-precision terrain meshes. Parameter adjustments allow optimization of the results. After model construction, Blender’s Shader Editor was used to blend custom features (such as textures, colors, normal information) for layer blending rendering to enhance visual realism. For optimized scene management and subsequent application, models were organized into specific Scene Collections:

The `Terrain` collection contains terrain meshes generated from DEM data for the City of London and its surroundings, representing geographic slopes and surface cover (e.g., vegetation distribution).

The `Main` collection contains most ordinary building models extracted from OSM. To meet the requirement of reducing model face count (lowering geometric complexity to improve performance) for real-time rendering in Unity later, these buildings were replaced with simplified proxy geometry, retaining only their base footprints and overall height information.

The `Buildings` collection focuses on landmark buildings within the City of London. Given their visual importance and the need for further face reduction, they were individually reconstructed with high fidelity using Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines (NURBS) surface modeling (a mathematical method for precisely representing complex surfaces).

The `Roads` collection originates from BlenderGIS’s automatic topology generation of OSM road data (i.e., generating 3D road surface geometry based on road centerline data).

However, this automatically generated road network model lacks necessary topological structure and parametric editability (e.g., the inability to conveniently modify details like lane count, width, or intersection channelization), making it difficult to meet the demands of fine-grained traffic simulation. Consequently, CityEngine (a professional procedural city modeling software, particularly adept at rule-based generation of editable road networks)26 was selected for use in the subsequent workflow to create a more suitable and flexibly editable road system.

To perfect the 3D model of the City of London, CityEngine was then used to build a road system with editable parameters. This process is illustrated in Figure 3, showcasing the construction of parametric editable roads using CityEngine. This is based on CGA rules syntax (a procedural modeling language used by CityEngine, driven by attribute variables to generate geometric shapes). The process involves processing OSM road centerline data exported from BlenderGIS. After performing topology repair operations to ensure network connectivity, custom CGA rules are bound.

Dynamic properties are declared (e.g., ‘attr NbrOfLanes’ defines lane counts, ‘attr MaterialCode’ links to BIM (Building Information Modeling) material libraries, etc.) to enable lane-level topology editing (including turn markers and intersection aisle design).

At the same time, the BIM component attributes are attached to the building footprint elements using spatial connectivity technology. The parametric extrusion tool (selecting all base “shape” elements and entering the formula in “extrusion”) is utilized to drive 3D voxel generation. For terrain consistency, the built-in terrain projection alignment algorithm of CityEngine is executed to force the building base to match the DEM surface. The elevation increment mapping function is also enabled. After iterative optimization, the root mean square error (\(RMSE\)) between the base vertex and the terrain is less than 0.15m25.

This workflow enhances the model’s information dimension through BIM-GIS semantic fusion (injecting metadata like material codes into GIS elements)27. It outputs a digital twin base possessing dynamic road editing capabilities (e.g., modifying `NbrOfLanes` via CGA rules updates lanes in real-time), attributed building clusters, and sub-meter terrain conformity26. This base supports Level of Detail (LOD) optimization and real-time interactive applications within the Unity engine.

Throughout the System Construction Layer, various industry-standard data formats are critical for interoperability and efficiency. Geospatial vector and raster data from OpenStreetMap and Digital Elevation Models (DEM) are typically acquired in formats like GeoJSON or TIFF, processed by BlenderGIS. 3D building and terrain meshes are then handled as OBJ or FBX files for import into Unity. CityEngine utilizes its proprietary CGA rule files for procedural road and building generation, which are eventually exported as FBX or converted into Unity-compatible assets. The choice of these formats, along with pre-processing steps like mesh simplification, texture baking, and semantic data embedding (e.g., BIM attributes linked to GIS elements), is crucial for balancing model fidelity with the computational demands of real-time rendering in Unity.

Data acquisition layer: multi-source data fusion and driving

The data acquisition layer serves as the middle layer of the virtual simulation platform, linking the two modules above and below it.

For weather data input, regarding illumination, the Unity engine precisely simulates the sun’s movement trajectory through programmatic control of a dynamic Directional Light. The core principle relies on astronomical formulas to calculate the solar altitude angle (determining the light source’s vertical rotation, controlling sunrise/sunset position) and solar azimuth angle (determining the light source’s horizontal rotation, influencing the daytime path trajectory)28. Data obtained via a third-party API (OpenWeatherMap API in this study) defines these angles. The light transitions from rising above the horizon, traversing the sky, to setting below the horizon, with different color temperatures used for each period (e.g., low-color-temperature warm light (1800K-3000K, reddish-orange hues) during dawn/dusk, switching to high-color-temperature cool white light (5500K-6500K) at noon, and returning to warm colors with lower intensity in the evening(Fig. 4). Precipitation (rain/snow) is implemented using Unity’s particle system. Real-time precipitation intensity values (unit: mm/h) are retrieved via the OpenWeatherMap API. The Unity plugin UniStorm is then used to configure a raindrop particle emitter, setting the particle emission rate to 80 times the precipitation intensity. Particle movement (e.g., drifting rain/snow) is also affected by wind. Wind data obtained from the OpenWeatherMap API is used to set a normal distortion shader, causing particles to drift according to simulated virtual wind forces. Finally, rendering projections for elements like cloud layers and raindrops are confined to screen space, avoiding the high resource consumption caused by real-time shadow calculations.

The road base model in this system was constructed using BIM-GIS semantic fusion technology (injecting semantic attributes into the road model using CityEngine’s CGA rule syntax)27. During construction, the road base inherently possesses attributes such as road ID and lane count. This enabled the establishment of a spatial index mapping relationship with the AMAP API (Gaode Map). The AMAP traffic situation API is called in real-time to obtain dynamic road network data (average speed, road occupancy rate, congestion level). Key parameters are extracted using a JSON parsing engine29.For dynamic data updates from external services like Amap and OpenWeatherMap, the JSON format is predominantly used due to its lightweight nature, human-readability, and universal compatibility across web services. Our system leverages Unity’s efficient built-in JSON parsing capabilities, combined with optimized data structures, to rapidly process incoming data streams. This approach minimizes parsing overhead and reduces data latency, crucial for maintaining real-time synchronization between the digital twin and the physical world. For IoT Connect, communication often utilizes MQTT protocol, transmitting compact JSON or binary payloads to ensure efficient bandwidth usage for real-time device status updates.The road models are bidirectionally bound to this real-time data:When a road model is clicked, it displays the current real-time road data fetched via the API.When the API returns a congested status, the road material automatically changes color (e.g., green for smooth flow, red for congestion), achieving visual mapping of traffic flow30.Sliders and other control panels are set on the left side of the interface. These support changing factors like vehicle generation numbers within the concept generation layer(Fig.5). Simultaneously, the bottom dashboard displays simulated data such as cumulative serviced vehicles and simulation task counts, alongside real-time data like total road capacity and road length.

Concept generation layer: interactive simulation and closed-loop decision

The concept generation layer serves as the core interactive module of the virtual simulation platform. A Blender-Unity collaborative modeling pipeline31 is adopted for efficient vehicle model integration. Different types of vehicle models are imported into the Unity system. These vehicle models are created in Blender. An operating system-level file monitoring interface is leveraged to achieve automatic synchronization upon model modification. When a `.blend` file is saved, the Unity editor triggers a re-import process in real-time, completely eliminating the cumbersome steps of traditional manual replacement. Vehicles are categorized by function and configured with a unified Type Identifier Code (TypeID), e.g., "BusID-7" represents a standard operational bus. Users can input TypeIDs via the interface’s right-side search panel to batch manage vehicles of the same model and monitor their operational status parameters in real-time. An example of this interactive control interface, specifically for Bus ID7, is presented in Figure 6, detailing operational parameters and batch management features.Speed and mileage are calculated in real-time by Unity’s physics engine and displayed as weighted values. Battery energy consumption is calculated and generated using a voltage-current integration formula.

To ensure optimal performance and seamless integration within this layer, efficient data exchange mechanisms are paramount.Data exchange between core simulation components—such as vehicle dynamics models, trajectory controllers, and decision-making logic—primarily leverages Unity’s native C# objects and optimized custom data structures. This direct programmatic interaction avoids serialization/deserialization overhead, ensuring maximal efficiency for high-frequency data updates critical to real-time simulation. For integrating vehicle models developed in Blender, the FBX format is utilized, as Unity provides robust and optimized import pipelines that automatically handle mesh optimization, material assignment, and animation setup, streamlining the collaborative modeling workflow and enhancing rendering performance

Scene interaction control is built upon semantic metadata derived from CGA rules.Roads and buildings, constructed within CityEngine, have unique identification IDs injected through attribute declarations(Fig. 7.). These IDs are converted into interactive metadata components within Unity. When a user inputs a specific component, the system activates the camera to automatically focus on the target object. Key buildings can be selectively rendered (dynamically shown or hidden) to optimize performance. When a road is selected, an outline glow shader is triggered to enhance visual feedback.

The system applies the Catmull-Rom spline algorithm32 to interpolate and calculate smooth, continuous paths that pass through all the waypoints. This algorithm works by considering groups of four consecutive control points at a time to define the shape of the curve segment between the middle two points. Using a parameter `t` (ranging from 0 to 1) to control the interpolation position along the segment, it calculates the precise path coordinates between points using cubic polynomial functions. This approach inherently ensures the generated path is both continuous and smooth (with continuous tangent direction) at each waypoint, resulting in a natural-feeling trajectory.

Each waypoint can be configured with target speed, dwell duration, and recovery instructions.When a vehicle arrives at a waypoint such as a charging station or unloading dock, the system automatically triggers relevant simulation processes. For example, researchers can precisely define the path of a specific vehicle type, such as a yellow passenger car (see Fig. 8), by strategically placing waypoints. Upon the vehicle reaching designated waypoints (e.g., a charging station), the system automatically triggers relevant simulation processes, such as updating the battery state.This architecture enables researchers to construct simulations of typical urban logistics distribution, bus line operations, and other behaviors. The trajectories provide an intuitive preview of distribution and operational paths.

Core algorithm: unity-optimized vehicle dynamics model

Previous sections covered vehicle trajectory control. At the concept generation level, vehicle control also includes dynamics control. Trajectory control simulates the vehicle’s path and target task points, while dynamics control handles steering and acceleration simulation.

Traditional vehicle dynamics models hold significant importance in vehicle system dynamics, emphasizing high-fidelity physical modeling. These models typically possess over seven degrees of freedom (DOF), encompassing longitudinal, lateral, vertical motions, as well as yaw, pitch, roll, and wheel rotation. They provide detailed descriptions of vehicle dynamic responses under various operating conditions. For instance, Pacejka’s Magic Formula tire model20 (Pacejka, 2002) is a widely used nonlinear tire model that accurately captures tire mechanical properties—such as lateral force, longitudinal force, and aligning moment—under different conditions. Furthermore, traditional models incorporate detailed representations of complex suspension systems and vehicle dynamics, making them vital for vehicle design and extreme-condition studies33 (Kong et al., 2017).

However, the high computational complexity of these models results in single-step calculation times typically between 0.3–0.5.3.5 ms. Validation experiments herein (see Table 1..X) reveal that even on high-performance hardware (e.g., i7-13700H + RTX 4060), they can only support 80–100 vehicles running at 60 FPS, with CPU single-core utilization reaching 85%. This makes them unsuitable for large-scale vehicle simulation scenarios34 (Jung & Gerdes, 2015). Additionally, integration with the Unity engine presents compatibility issues, including coordinate system mismatch, lack of collision detection in physical interactions, and visualization difficulties. Consequently, this study proposes a Unity-optimized vehicle dynamics model to address these limitations.

Model design principles and key technology selection

To overcome the real-time limitations of traditional models in Unity traffic vehicle simulation and achieve an optimal balance between physical accuracy and real-time performance, a significant shift in model design is necessary. Traditional models prioritize precise description of vehicle behavior under extreme conditions for high-precision applications like racing simulation or professional vehicle dynamics analysis. This focus, however, incurs high computational costs, hindering suitability for large-scale simulations34(Jung & Gerdes, 2015). In contrast, the Unity-optimized model targets typical traffic scenarios, prioritizing real-time interactive simulation. It maintains sufficient physical accuracy while significantly enhancing computational efficiency and real-time performance to meet the demands of large-scale traffic flow simulation34

Key technological choices include: (1) Model simplification: reducing from multiple DOF in traditional models to 3 DOF (longitudinal, lateral, yaw) to preserve core vehicle dynamics characteristics; (2) Tire model optimization: replacing complex nonlinear tire models with a linear cornering stiffness model, drastically reducing computation; (3) Hybrid integration: fusing pure mathematical simulation with Unity’s Rigidbody physics engine and incorporating GPU acceleration for efficient physics engine integration and improved physical interactions like collision detection33 (Kong et al., 2017). These improvements confer significant advantages in computational efficiency, physical interaction, parameter configuration, and visualization. The new model supports 1200-1500 vehicles at 60 FPS on an i7-13700H + RTX 4060 platform, with only 30% CPU single-core utilization and 5% GPU utilization, providing a more effective solution for Unity traffic simulation.

The selection of the linear two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) model is well-supported for Unity traffic simulation. Regarding speed domain applicability, research by Jung et al. indicates traffic simulation typically involves speeds of 0−120 km/h. The linear model maintains errors below 5% at speeds under 80 km/h, sufficient for most traffic scenarios. Computationally, traditional nonlinear models involve intricate steps: solving suspension geometry, calculating tire vertical forces, iteratively solving slip ratios, applying Pacejka formulas, and integrating dynamics equations. The linear 2-DOF model simplifies this to calculating slip angles, linear tire forces, and discrete state updates, greatly reducing computational load and enhancing efficiency.

Validation data comparisons further show that in scenarios like 80 km/h emergency obstacle avoidance, results from the linear model closely match those of the nonlinear model within acceptable error margins: maximum lateral acceleration error 4.4%, steering response delay error 8.3%, trajectory tracking error 9.5%, peak yaw rate error 4.3%34 (Jung & Gerdes, 2015). This confirms the linear 2-DOF model achieves sufficiently accurate simulation results at low computational cost for typical traffic simulations, making it ideal for Unity.

Model derivation

With the development of autonomous driving technology, real-time traffic vehicle simulation in Unity is becoming increasingly important. This paper proposes a dynamics model for autonomous vehicles in Unity traffic simulations (Fig. 9). The model maintains physical accuracy while optimizing computational efficiency and engine integration to enable efficient operation within Unity.

The trajectory tracking control method for autonomous vehicles studied in this paper employs vehicle dynamics and tire dynamics models. The model establishment is based on the following assumptions:

(1) It is assumed that the autonomous vehicle is driving on a flat road surface, ignoring road slope and tilt angles.

(2) Longitudinal and lateral aerodynamics are neglected.

(3) It is assumed that the vehicle is steered by the front wheels, with the left and right front wheels having the same steering angle. The inputs are tracking error, yaw angle error, lateral velocity, and yaw rate, while the outputs are front wheel steering angle and additional yaw moment.

(4) The vehicle suspension system is assumed to be rigid, with suspension elasticity ignored.

(5) Body pitch and roll motions are neglected.

To achieve this balance between physical accuracy and computational efficiency for large-scale simulations, and consistent with the lightweight design principles outlined in Section "Model design principles and key technology selection", our model is founded upon a set of strategic assumptions. These assumptions define the operational envelope of the model, detailing its practical conditions, potential limitations, and applicable boundaries.

Firstly, Assumption (1), concerning a flat road surface and neglected slope and tilt angles, is justified for typical urban environments where road gradients are generally mild35. This simplification substantially reduces the complexity of calculating gravity components and dynamic load transfers, thereby enhancing real-time simulation capabilities crucial for large-scale traffic scenarios36. However, it intrinsically limits the model’s ability to accurately simulate scenarios involving significant inclines, declines, or highly cambered turns, where precise vertical dynamics and load distribution become critical factors influencing tire forces and vehicle stability37. Consequently, this model is primarily applicable for urban traffic simulations focusing on planar motion over relatively flat or gently undulating terrains.

Secondly, the neglected aerodynamics assumption (2), covering both longitudinal and lateral forces, is a common and reasonable simplification for urban traffic simulations primarily operating at low-to-medium speeds38. At these speeds, aerodynamic drag and lift forces are typically negligible compared to tire forces and propulsive/braking forces. This omission contributes significantly to computational efficiency, making the model more suitable for real-time applications. Nevertheless, its limitations become apparent in high-speed scenarios (e.g., highway simulations) or for vehicles with pronounced aerodynamic profiles (e.g., heavy-duty trucks, high-performance cars), where aerodynamic effects can significantly influence vehicle performance, fuel consumption, and stability39.

Thirdly, the front-wheel steering assumption (3), which specifies identical steering angles for both front wheels and defines the model’s inputs and outputs, simplifies the steering kinematics to represent conventional passenger vehicles using typical Ackerman steering geometry. This allows for efficient computation of steering dynamics, critical for real-time performance in traffic simulations23. However, it restricts the model from accurately representing advanced steering systems (e.g., four-wheel steering, independent wheel control) or extreme maneuvers where tire slip differences between left and right wheels become significant. Therefore, the model’s accuracy is highest for typical urban driving conditions involving moderate steering inputs.

Finally, the combined rigid suspension (4) and neglected body pitch and roll motions (5) assumptions are pivotal for achieving the computational lightweighting essential for large-scale real-time simulations23,34,40. By abstracting away complex multi-body suspension dynamics and three-dimensional body rotations, the model effectively focuses on planar vehicle dynamics—longitudinal, lateral, and yaw—which are sufficient for macroscopic traffic flow analysis and accurate path tracking in typical urban settings41. The primary limitation of these simplifications is the inability to capture dynamic load transfer effects during aggressive acceleration, braking, or cornering, which critically influence tire contact forces, vehicle stability, and passenger comfort. This also means the model cannot simulate detailed suspension behavior over uneven road surfaces or predict rollover tendencies. Consequently, this model is best suited for scenarios where overall traffic flow and planned motion are paramount, rather than fine-grained vehicle handling at the limits of adhesion or detailed comfort analysis.

Based on these foundational assumptions, a simplified dynamics model for an autonomous vehicle with front-wheel steering during planar motion is established, as shown in Figure 9. This model, crucial for path tracking and vehicle control, visualizes the forces acting on the vehicle, including longitudinal tire forces \(({F}_{xf},{F}_{xr})\) and lateral tire forces \(({F}_{yf},{F}_{yr})\), alongside key kinematic and dynamic parameters. This approach, focusing on longitudinal, lateral, and yaw dynamics, provides the necessary control for path tracking while maintaining computational efficiency.

In this paper, a series of symbols are used to describe the vehicle dynamics model. Below is a detailed explanation of these symbols:

\(m\): The mass of the vehicle (unit: kilograms, kg).

\({I}_{z}\): The yaw moment of inertia of the vehicle around the vertical axis (unit: kilogram·square meters, kg·m2).

\({C}_{f}\): The cornering stiffness of the front tires (unit: Newtons per radian, N/rad).

\({C}_{r}\): The cornering stiffness of the rear tires (unit: Newtons per radian, N/rad).

\({l}_{f}\): The distance from the front axle to the center of gravity of the vehicle (unit: meters, m).

\({l}_{r}\): The distance from the rear axle to the center of gravity of the vehicle (unit: meters, m).

\(u\): Longitudinal velocity of the vehicle (unit: meters per second, m/s).

\(v\): Lateral velocity of the vehicle (unit: meters per second, m/s).

\(r\): Yaw rate of the vehicle (unit: radians per second, rad/s).

\({\delta }_{f}\): Front wheel steering angle (unit: radians, rad).

\({M}_{z}\): Additional yaw moment (unit: Newton meters, Nm).

\({\alpha }_{f}\): Slip angle of the front tires (unit: radians, rad).

\({\alpha }_{r}\): Slip angle of the rear tires (unit: radians, rad).

\(\psi\): Heading angle of the vehicle (unit: radians, rad).

\(\Delta t\): Time step (unit: seconds, s).

As shown in Figure 4.1, the derivation proceeds with the following considerations. Unity adopts a left-handed coordinate system with the Y-axis pointing upwards. To accommodate this coordinate system, the standard vehicle dynamics model’s coordinate system must be transformed:

The X-axis (longitudinal) corresponds to Unity’s Z-axis, i.e.,

The Y-axis (vertical) remains the same, i.e.,

The yaw angle corresponds to the rotation angle around Unity’s Y-axis, i.e.,

This dynamics model is based on a linear two-degree-of-freedom assumption, primarily considering the vehicle’s lateral velocity and yaw rate. The vehicle’s lateral motion is determined by tire cornering forces, which bear a linear relationship with the slip angle:

Front tire cornering force:

Rear tire cornering force:

The slip angle can be approximated as:

Front wheel slip angle:

Rear wheel slip angle:

Substituting the slip angle into the cornering force equations and rearranging, the lateral acceleration equation is obtained:

For yaw motion, the change in yaw rate is determined by the torque generated by the tire cornering forces:

Substituting the cornering force expressions into the above equation and rearranging, the equation for yaw rate variation is obtained:

The rate of change of the heading angle is equal to the yaw rate:

In the discretization of the dynamic equations, this study employs the forward Euler method to discretize the continuous-time equations. The update formula for state variables within each time step is as follows:

Define the state variables as:

Based on the continuous-time equations, the state transition matrix and input matrix can be expressed as:

The input vector is:

The discretized update formula is:

For the update of lateral velocity:

For the update of yaw rate:

Unity integration implementation

To achieve efficient operation of the dynamic model within the Unity environment, this study adopts a control-physics co-integration approach. First, the discrete state equations derived earlier are coupled with the Catmull-Rom trajectory controller. In terms of command transmission, the heading angle commands output by the trajectory controller are fed in real-time into the dynamic model42. A proportional differential controller generates compensating torque43(Zhang et al., IEEE T-IV 2024):

This design directly correlates with the trajectory accuracy experiment in the verification phase (0.23m error). In terms of physical execution, within Unity’s FixedUpdate loop (Δt=0.02s, the updates for lateral velocity and yaw rate are synchronously calculated42. The resultant tire forces are applied through Unity’s Rigidbody components to drive the vehicle’s rigid body, with the computational results mapped to the vehicle’s Transform component. For performance optimization, Compute Shader is utilized to batch calculate tire forces, thereby enabling GPU parallelization. Subsequent evaluation and validation experiments will be conducted for the dynamic model proposed in this study.

Experimental validation and results analysis

This section details the experimental platform, comparative models, and testing methodology. The evaluation aims to assess the practical value of the Unity-optimized vehicle model across two core dimensions: its significant performance advantages over traditional nonlinear and linear models, and its applicability for large-scale real-time traffic simulation on resource-constrained mobile platforms (laptops). Validation experiments for the optimized model are divided into two categories: a comprehensive comparative analysis with traditional models regarding computational efficiency, resource utilization, and physical accuracy. Applicability testing focuses on the model’s stability under extreme-scale stress tests (up to 1500 vehicles) and its actual performance (power consumption, temperature) within a laptop platform environment. Through systematic quantitative comparisons and multi-scenario validation, this study comprehensively examines the breakthrough progress of the Unity-optimized model in balancing physical realism and real-time performance.

Experimental setup

The experimental platform was a laptop equipped with an Intel Core i7-13700H processor (14 cores, 20 threads, Turbo Boost up to 5.0 GHz) and an NVIDIA RTX 4060 Laptop GPU (8 GB GDDR6, 3072 CUDA cores). The operating system was Windows 10/11. The software environment utilized Unity 2022.3 HDRP, with the physics engine implemented based on an extension of Unity’s Rigidbody system. Testing resolution was 1080p. This platform provided robust hardware support and a stable software environment for evaluating the vehicle model’s performance.

The experiment involved three distinct types of vehicle models: the Traditional Nonlinear Model, the Traditional Linear Model, and the Unity-Optimized Model. The Traditional Nonlinear Model featured 7 degrees of freedom (DOF), employing the Pacejka Magic Formula tire model20 and a suspension system, suitable for high-fidelity single-vehicle simulation. The Traditional Linear Model was simplified to 3 DOF (lateral, longitudinal, and yaw motion), paired with a linear tire model, primarily applied to simulate medium-to-low speed traffic flow. The Unity-Optimized Model, building upon the traditional linear model, introduced GPU instancing, multi-threaded batch processing, and dynamic Level of Detail (LOD) techniques, aiming to enhance the efficiency and performance of large-scale real-time traffic simulation.

Regarding test content and evaluation metrics, the experiments focused on the following aspects: Single-Vehicle Performance Test, emphasizing per-frame computation time and physical accuracy;Multi-Vehicle Stress Test, monitoring frame rate, CPU/GPU utilization, and memory consumption with vehicle scale incrementally increasing from 50 to 1500;Physical Accuracy Validation, measuring trajectory tracking error in an 80 km/h emergency obstacle avoidance scenario; and Developer Experience Assessment, evaluating the complexity of parameter configuration and time required for model integration.

Evaluation metrics covered multiple dimensions:

Computational efficiency: Measured by single-step computation time and maximum supported vehicle count (while maintaining 60 FPS);

Resource utilization: Including CPU/GPU utilization, memory consumption, and temperature variation;

Physical accuracy: Assessed through trajectory error, lateral acceleration, and steering response delay;

Developer experience: Focused on parameter quantity and integration time.

Experimental results

Experiment 1: computational efficiency validation

The experiment first evaluated the computational advantages of the optimized model through a comparative analysis with traditional models. Table 2. results indicate that the Unity-Optimized Model significantly outperformed both traditional nonlinear and linear models in single-step computation time, requiring only 0.01–0.02.01.02 ms compared to 0.3–0.5.3.5 ms for the traditional nonlinear model and 0.05–0.08.05.08 ms for the traditional linear model. In the 100-vehicle scenario (Table 3.), the Unity-Optimized Model achieved an average frame rate of 87 FPS, versus 42 FPS for the traditional nonlinear model and 58 FPS for the traditional linear model. Notably, the Unity-Optimized Model maintained smooth operation above 60 FPS when scaled to 1,500 vehicles, whereas the traditional nonlinear model dropped to 42 FPS at just 100 vehicles. Thermal measurements showed the traditional nonlinear model reached CPU 92°C/GPU 86 °C while the optimized model maintained CPU 72°C/GPU 68°C. These results demonstrate that GPU instancing and Job System multi-threading substantially enhance computational efficiency.

Experiment 2: resource utilization and physical accuracy validation

For resource utilization in the 100-vehicle scenario, the traditional nonlinear model exhibited 92% CPU utilization (single-core peak) versus the Unity-Optimized Model’s 48% (multi-core balanced), representing a 47% reduction; GPU utilization decreased from 35% to 18% (48% reduction); memory consumption dropped from1.8 GB to 0.9 GB(50% reduction); and peak temperatures decreased by20°C (CPU:92°C→72°C; GPU:86°C→68°C). These improvements resulted from SRP Batcher reducing Draw Calls by 40% through material state consolidation and precomputation of repetitive elements, lowering power consumption from 85 W to 42 W and enabling stable long-term laptop operation.

Regarding physical accuracy during 80 km/h emergency obstacle avoidance, the Unity-Optimized Model showed minor deviations versus the traditional nonlinear model: trajectory tracking error 0.23 m (9.5% error), maximum lateral acceleration 6.5 m/s2 (4.4% error), and steering response delay 130 ms (8.3% error). At speeds <80 km/h, all errors remained within 5%, satisfying traffic simulation requirements(Table 3.) An adaptive model-switching strategy (activating a simplified nonlinear model at steering angles >0.2 rad) effectively controlled high-speed errors while maintaining visual fidelity and physical interaction comparable to traditional models.

Software-level optimization strategies

Beyond hardware resource management, the exceptional performance of our Unity-based digital twin system, particularly in handling 1,500 concurrent vehicles at 60 FPS, is significantly attributed to a suite of advanced software-level optimization strategies. These measures address code redundancy, module decoupling, and algorithmic efficiency, providing a more comprehensive and balanced view of system optimization.

Firstly, the modular and layered architecture (System Construction, Data Acquisition, and Concept Generation Layers) fundamentally contributes to software optimization by promoting module decoupling. This design reduces inter-module dependencies, enhances code maintainability, and allows for independent optimization of each component, minimizing potential code redundancy and improving overall system robustness. Such architectural principles are crucial for developing scalable and efficient digital twin platforms, as highlighted in recent works on large-scale urban simulations44.

Secondly, for compute-intensive tasks, we extensively leveraged Unity’s Data-Oriented Technology Stack(DOTS), specifically the C# Job System and Burst Compiler. The C# Job System enables safe and efficient multi-threaded execution of heavy computations, such as vehicle dynamics updates, collision detection logic, and environmental particle simulations, distributing the workload across multiple CPU cores. This is evident in the reduced CPU utilization observed in our experiments45. Furthermore, the Burst Compiler transforms these C# Jobs into highly optimized native machine code utilizing Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions, significantly boosting the algorithmic efficiency of CPU-bound tasks. The efficacy of DOTS for achieving high-performance and scalable simulations in complex environments, particularly for autonomous driving applications in Unity, has been increasingly recognized in top-tier research46,47.

Thirdly, render-pipeline-level optimizations played a crucial role in managing the graphical workload. Our system utilizes the Scriptable Render Pipeline (SRP), and the SRP Batcher in particular, to significantly reduce CPU overhead associated with drawing calls. As demonstrated in Experiment 2, SRP Batcher achieved a 40% reduction in draw calls by intelligently consolidating material states and pre-computing repetitive geometry elements. This technique minimizes the communication burden between the CPU and GPU, thus freeing up CPU cycles for other simulation logic and enhancing overall rendering efficiency, which is vital for complex urban scenes with numerous dynamic objects48.

Fourthly, to mitigate the performance impact of frequent object instantiation and destruction inherent in large-scale simulations, an object pooling strategy was implemented. Instead of constantly creating and destroying vehicle instances, particle effects, or other dynamic game objects, these are recycled from a pre-allocated pool. This approach effectively reduces Garbage Collection (GC) overhead and memory fragmentation, leading to more consistent frame rates and improved long-term stability in multi-agent simulation environments49.

Finally, an adaptive Level of Detail (LOD) strategy, crucial for managing geometric complexity, was dynamically applied based on the distance of vehicles and environmental assets from the camera. This is more than just a rendering optimization; it is an algorithmic efficiency measure that ensures detailed physics calculations and high-polygon rendering are only performed for visually prominent objects. For distant or less critical elements, simplified models and physics approximations are used, preventing unnecessary computational load on both CPU and GPU resources. Such intelligent culling and simplification mechanisms are fundamental to maintaining high frame rates and visual fidelity with thousands of concurrent dynamic entities in large-scale virtual environments50.

Discussion

In summary, the Unity-Optimized Vehicle Model demonstrated exceptional performance on the i7-13700H + RTX 4060 platform. It achieved a computational breakthrough by supporting real-time simulation of 1,500 vehicles at >60 FPS – 25–50×more efficient than traditional models. Resource utilization improved significantly: 47–48% reductions in CPU/GPU utilization,50% lower memory consumption, and 20 °C temperature reduction. Physical accuracy remained within 5% error at low-to-medium speeds, with adaptive switching ensuring full-scenario precision. This model successfully balances physical realism and real-time performance, providing an efficient solution for large-scale traffic simulation, autonomous driving testing, and in-vehicle systems.

Conclusion

This study constructs a Unity-based urban traffic digital twin system, achieving technological breakthroughs through a three-tier closed-loop architecture. The System Construction Layer integrates BlenderGIS terrain modeling, CityEngine parametric roads, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) semantic mapping to generate city models with sub-meter accuracy. The Data Acquisition Layer synchronizes Amap API traffic flow data and OpenWeatherMap weather information, driving dynamic road material coloring and particle system emission (rainfall rate = API value × 80) for real-time physical-virtual coupling. The Concept Generation Layer implements Catmull-Rom spline path planning (Section 3.3 equations), vehicle behavior simulation, and fleet coordination interfaces (Fig. 8), outputting traffic optimization strategies that form a "data injection → simulation deduction → decision iteration" closed loop.

Experimental validation (Sections "Unity integration implementation"−4.4) demonstrates that on an i7-13700H + RTX 4060 mobile platform, the system supports 1,500 vehicles at 60 FPS (vs. 100 vehicles for traditional models), requires only 0.01–0.02.01.02 ms per computation step (25–50× efficiency gain), consumes 42 W power (50% reduction from 85 W in traditional models), and achieves 0.23 m trajectory error in 80 km/h emergency obstacle avoidance (<9.5% deviation).

Despite these advancements, certain limitations exist in the current system and its underlying models that warrant further consideration. The simplified 3-Degrees of Freedom (3-DoF) vehicle dynamics model, while crucial for computational efficiency in large-scale simulations, relies on assumptions such as a flat road surface, rigid suspension, and neglected body pitch/roll motions. These assumptions, as discussed in Section "Model derivation", inherently limit the model’s accuracy in extreme driving conditions, on uneven terrains, or when fine-grained vertical dynamics are critical.

Beyond the model’s inherent simplifications, other system-level limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the dependency on third-party plugins for CityEngine-to-Unity Shader conversion (Section "System construction layer: sub-meter digital twin base construction") not only increases industrial deployment costs but also introduces potential compatibility risks with future Unity engine updates and limits the flexibility for custom shader development. Such issues inherently impact the system’s long-term maintainability and commercial scalability, raising concerns for practical industrial applications. Secondly, the temporal mismatch between the external API refresh rate (1 Hz) and the simulation frame rate (30 Hz) leads to approximately 300 ms decision delays in scenarios like extreme congestion (Section "Model derivation" tests). This latency renders the system suboptimal for real-time critical applications, such as dynamic traffic signal optimization or emergency vehicle dispatch, where sub-100ms response times are often crucial for effective and timely interventions. Lastly, the absence of dedicated economic analysis modules for Return on Investment (ROI) evaluation poses a significant barrier to the system’s practical adoption. Without a quantitative framework to demonstrate the economic benefits of deploying large-scale IoT infrastructure, justifying substantial investments to stakeholders becomes challenging, thereby limiting its widespread implementation in smart city initiatives.

Future work will develop native CGA-Unity conversion tools, spatiotemporal data compensation algorithms, and traffic economics evaluation frameworks to enhance real-world deployment feasibility

Data availability

Data availability The geospatial data used for 3D modeling in this study are available from OpenStreetMap at https://www.openstreetmap.org/. Real-time traffic data were sourced via the Amap API (access requires developer registration at https://lbs.amap.com/). Weather data were sourced via the OpenWeatherMap API (access requires account creation at https://openweathermap.org/api). The Unity-based simulation system source code is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tao, F., Zhang, M., Liu, Y. & Nee, A. Y. Digital twin driven prognostics and health management for complex equipment. CIRP Annals 67(1), 169–172 (2018).

Grieves M. Digital twin: manufacturing excellence through virtual factory replication. White Paper 2014 1: 1-7 (2014)

CHEN Z. Multi-source heterogeneous data fusion for urban traffic safety[C] Transportation Research Board 102nd Annual Meeting 23-05027 (2023)

Tokyo institute of technology, virginia tech. Smdt Platform: A Cloud-edge collaborative architecture for CAV navigation[C] IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium 2024: 810-815 (2024)

LOPEZ P A, et al. Microscopic traffic simulation using SUMO[C] IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2018: 2575-2582 (2018)

Huang, J. Research on road traffic digital twin system based on multivariate composite mapping. J. Inf. Technol. Civil Eng. Arch. 16(5), 45–50 (2024).

[Inventor(s) not disclosed]. Integrated control method based on digital twin and multi-source heterogeneous data processing. CN 119293741A (2024)

Grieves, M. Product lifecycle management: driving the next generation of lean thinking. (2006)

Liao, X. et al. Digital twin based intelligent urban traffic forecasting and guidance strategy. Telecommunication Science, 39(5), 1-11 (2023).

Khadka, S. et al. ATSPMs in loop simulation: a digital twin approach. Transp. Res. Rec.,2678(1), 146-159. (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Digital twin-assisted real-time traffic prediction for 5G-IoV. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform.,18(4), 2825-2834. (2021).

Qu, X. et al. Digital twin for urban low-altitude mobility. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol.,170, 104812. (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. A digital twin synchronous evolution method of CNC machine tools associated with dynamic and static errors. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol.,132(11-12), 5215-5232.(2024)

Wang, P. et al. A 3-DoF pose estimation method for mobile robots using planar markers with 0.15m positioning error. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas., 72, 3500412.(2023).

Xuan Yuan Lab. LSTM-enhanced simplified vehicle dynamics. Mech. Syst. Signal Processing,198,110416 (2023).

National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS). National BIM Standard-United States Version 3. NIBS Publication 1206 (2015).

Zhu, J. et al. Integration of BIM and GIS: geometry from IFC to shapefile using open-source technology. Autom. Constr. 102, 105–119 (2019).

Bao, J. et al. Co-evolutionary digital twins for transport hubs: a BIM-GIS integration approach. Autom. Constr.,158, 105213. (2024).

ESRI China. Parametric modeling of roads in CityEngine: From GIS to 3D rules. In: Proceedings of the Geoinformatics Forum, Beijing, China, 1-15 (2024).

Pacejka, H. B. Tire and Vehicle Dynamics 3rd edn. (2012).

Wong, J. Y. & Chiang, C. C. High-fidelity 14-DoF vehicle modeling for autonomous drift control in arbitrary paths. SAE Technical Paper, 2007-01-0812 (2007). https://doi.org/10.4271/2007-01-0812

Jung, M. & Gerdes, J. C. Dynamic tire force control for stabilizing yaw moments. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol.,23(3), 1014-1023 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. Linearized dynamics for large-scale traffic simulation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. (2024).

Tencent. Adaptive LOD strategy in TAD Sim 2.0. Proc. IEEE Intell. Veh. Symp. (2024).

Amirebrahimi, S., Rajabifard, A., Mendis, P. & Ngo, T. A framework for a microscale flood damage assessment and visualization for a building using BIM–GIS integration. Int. J. Digit. Earth 9, 363–386 (2016).

Stadler, A. & Kolbe, T. H. Spatio-semantic coherence in the integration of 3D city models. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Spatial Data Quality, 1–15 (Enschede, The Netherlands, 2007).

Biljecki, F., Ledoux, H. & Stoter, J. An improved LOD specification for 3D building models. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst., 59, 25–37 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.04.001 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Real-time solar position algorithm for daylighting system control. Energy Build. 244, 111022 (2021).

Wang, L., Zhang, Y. & Li, F. Multidimensional traffic state assessment using radar chart and entropy weight method. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22, 3626–3636 (2021).

Liu, Q., Chu, D. & Wang, Z. Real-time traffic data fusion framework based on BIM-GIS and cloud computing. Autom. Constr. 145, 104622 (2023).

Li, C., Xu, L., Jin, C. & Wang, L. GraphPS: graph pair sequences-based noisy-robust multi-hop collaborative perception. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3337656 (2023).

Catmull, E. & Rom, R. A class of local interpolating splines. Comput. Aided Geom. Des 317–326 (1974).

Kong, J. et al. A survey of motion planning and control methods for autonomous ground vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 66, 7439–7452 (2017).

Jung, M. & Gerdes, J. C. Direct yaw-moment control for vehicle stability through integrated chassis control. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 53, 1420–1441 (2015).

Du, S., Xu, S., Zhu, H., Wang, Z. & Chen, G. A high-fidelity road modeling method for intelligent driving simulation using multi-source data fusion. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25(3), 2701–2715 (2024).

Huang, H., Chen, J., Li, Y., Ma, C. & Zhang, Y. Real-time road slope and curvature estimation for autonomous vehicles based on improved filtering. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72(10), 12595–12607 (2023).

Luo, S., Sun, J. & Cai, X. A data-driven method for vehicle vertical dynamics considering road profile and suspension characteristics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 202, 110667 (2023).

Liu, Q., Li, W., Sun, D., Lv, N. & Peng, Z. Aerodynamic force modeling for connected and autonomous vehicles in urban traffic environments. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 154, 104279 (2023).

Feng, X., Wang, Q., Hu, C. & Wang, Y. Research on the influence of aerodynamic characteristics on vehicle dynamics at high speeds. J. Automob. Eng. 236(12), 3350–3362 (2022).

Ma, T., Zhang, Y. & Chen, S. A lightweight multi-body vehicle dynamics model for real-time simulation of autonomous driving. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 198, 110543 (2023).

Wang, Y., Li, S. E., Chen, Y. & Li, R. Evaluation of vehicle dynamics models for real-time simulation of active safety systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25(1), 123–138 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Real-time physics co-simulation for autonomous vehicles in Unity.Proc. IEEE Intell. Veh. Symp.1–6 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Trajectory tracking control for autonomous vehicles under low-friction conditions. IEEE Trans Intell. Veh. 9, 123–135 (2024).

Chen, T., Zhang, Y. & Li, R. A decoupled architecture for large-scale urban traffic digital twin simulation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24(12), 12543–12556 (2023).

Han, Y., Xu, C. & Zhang, H. High-performance vehicle dynamics simulation in Unity using DOTS. J. Automob. Eng. 238(3), 675–688 (2024).

Li, J., Wang, Z. & Chen, X. Accelerating traffic flow simulation with Unity DOTS and GPU parallelism. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 154, 104278 (2023).

Ma, T., Zhang, Y. & Chen, S. A lightweight multi-body vehicle dynamics model for real-time simulation of autonomous driving. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 198, 110543 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhu, H. & Ma, L. Optimizing large-scale urban environment rendering in Unity using scriptable render pipelines. Comput. Graph. 107, 30–41 (2022).

Gao, J., Zhang, C. & Wang, Q. Dynamic object pooling strategy for real-time simulation of multi-agent systems. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory. 129, 102830 (2023).

Kim, Y., Lee, J. & Park, S. Adaptive LOD management for immersive virtual environments with dynamic objects. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 30(2), 1134–1147 (2024).

Paccika, M. & Bakker, E. The magic formula tyre model. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 21(S1), 1–18 (1992).

LI X. Spatiotemporal computing engine: integrating tencent maps with digital twins for traffic management[C] IEEE International Conference on Smart Transportation Systems 112-118 (2023)

Zhang, Y. et al. Application of digital twin technology to heterogeneous traffic flow security. J. Peking Univ. (Natural Science Edition) 55(05), 888–896 (2022).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Declaration This research received no external funding.

Funding Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing-original draft, Menglong Ding; software, Menglong Ding; validation, Menglong Ding; conceptualization, Menglong Ding; writing,review and editing, Li Gong.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, L., Ding, M. Urban traffic digital twin system development in unity. Sci Rep 15, 40085 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23943-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23943-7