Abstract

Urban renewal initiatives have accelerated the frequency of deep excavation projects implemented in close proximity to heritage structures. In soft soil regions, the nonlinear deformation behavior of soil creates substantial risks for the structural safety and long-term preservation of heritage buildings. Focusing on material degradation and pronounced deformation sensitivity of heritage buildings, this paper systematically analyzes the structural response to adjacent excavation through integrated finite element modeling. For a foundation pit excavation near a protected masonry heritage structure, the composite support scheme integrating TRD cement-soil cutoff walls, H-section steel beams, concrete horizontal bracing, and alternate bay excavation techniques effectively limited structural settlement to 2.43–3.13 mm, well below the 3.5 mm damage control threshold. Close correlation between monitoring data and numerical predictions confirmed the reliability of the modeling approach. Furthermore, numerical analysis validates that the code-prescribed soil displacement thresholds serve as upper-bound advisory limits for mitigating heritage structure damage, with case study calibration indicating a 30% reduction is warranted when considering horizontal soil displacement impacts. The developed technical pathway integrating “heritage structure deformation resistance assessment - excavation scheme optimization - preventive conservation implementation” not only provides actionable guidance for heritage-adjacent excavations but also offers transferable value for similar engineering projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of urban renewal initiatives, deep excavation projects are increasingly being undertaken in densely built-up urban areas in close to heritage buildings, this posing substantial geotechnical and structural engineering challenge1,2. As the pit walls lose lateral support during foundation pit excavation, the soil moves toward the free face (inside the pit) due to self-weight and stress release, causing ground settlement around the pit3,4,5. This movement is transmitted through the soil to the foundations of adjacent buildings. If the building’s foundation is shallowly buried, the settlement difference may exceed the building’s tolerance limit, resulting in uneven settlement of the foundations6, wall cracks7, or even structural inclination8. For buildings with pile foundations, lateral soil displacement and lateral forces will cause additional deformation and bending moments in the piles9,10. Furthermore, construction activities such as piling11, excavator operations12, and heavy vehicle movement generate vibrations that propagate through the soil to adjacent buildings13. Vibrations reduce the friction between soil particles and cause a transient increase in pore water pressure14, which may trigger liquefaction of saturated sandy soil and lead to a sudden drop in foundation bearing capacity.

Historical structures demonstrate considerable deterioration in both structural integrity and material characteristics owing to their advanced age and prolonged exposure to environmental factors. Taking masonry structures as an example, prolonged environmental erosion and sustained loading lead to significant deterioration of mortar strength. Test data indicate that the compressive strength may be reduced to merely 25% of its original design value15,16,17. Such material degradation in historic buildings exhibits substantially lower deformation tolerance compared to modern structures18,19. The complexity is further compounded by the fact that structures from different historical periods employed distinct construction techniques and material compositions, resulting in highly nonlinear mechanical responses. For instance, timber structures with mortise-and-tenon joints may exhibit distinctive hysteretic behavior under lateral deformation, while masonry arch structures demonstrate particular sensitivity to differential settlement. These unique characteristics render conventional excavation deformation control standards inadequate for cultural heritage preservation requirements20,21.

Engineering accident case studies reveal that construction-induced damage to historic buildings from deep excavation engineering has been a recurring problem22,23. These incidents reveal the limitations of conventional design approaches: on one hand, the empirical formula-based limit equilibrium method fails to accurately predict the nonlinear deformation behavior of soft soils. On the other hand, current regulations inadequately account for the unique characteristics of heritage structures and lack specific deformation control criteria.

With the advancement of computer technology, numerical simulation has gradually emerged as an innovative research tool. Finite element analysis has achieved sophisticated modeling capabilities that can account for complex factors such as soil stiffness characteristics at small strains and nonlinear soil-structure interactions at retaining system interfaces24,25. Numerical analysis methods are of great reference value for understanding the mechanism of how soil displacement affects heritage buildings. They help researchers qualitatively grasp how the settlement caused by foundation pit excavation is transmitted to building structures and the possible deformation trends of the structures26. However, their role in practical engineering applications, especially in guiding the design of foundation pit engineering in advance, has not been fully exerted. The “safe deformation threshold” for heritage buildings still relies on empirical standards. For example, Burd et al.27 proposed a simplified 2D assessment model to determine the value of characteristic strain, corresponding to the damage, but it has not been converted into foundation pit design parameters. Schuster et al.28 noted that while the model developed from the collected foundation pit design data had considerable applicability, it should be borne in mind that it may only be a first-order approximation. Prosperi et al.29 noticed that the limit values of the settlement parameters (i.e., differential settlement) proposed in national design codes and guidelines were too optimistic, and they should be determined based on the building’s feature.

In conclusion, ensuring the safety of heritage structures necessitates establishing a comprehensive control system that integrates the entire process from site investigation and design to construction and monitoring. However, relying solely on design Standards30,31 or empirical design practices often fails to prevent secondary damage to heritage structures that have already undergone conservation measures. Therefore, establishing a technical framework encompassing “heritage structure deformation resistance assessment - excavation scheme optimization - preventive conservation implementation” carries significant engineering value. The procedure is as follows: first, use finite element software to perform numerical simulation analysis to evaluate the deformation resistance of the heritage building, predict the degree and scope of damage to the heritage building caused by deformation induced by adjacent foundation pit excavation; then set corresponding deformation control thresholds; finally, feedback the evaluation and analysis results to the project construction unit and relevant management departments, optimize the design scheme if necessary, and take targeted protection measures for the vulnerable parts of the heritage building. This paper systematically analyzes the impact mechanisms of excavation construction on heritage structures, with particular emphasis on two numerical simulation-based deformation resistance assessment methodologies. Through case study validation, the research demonstrates the feasibility of this technical approach, thereby providing both scientific foundations and practical guidance for the design and implementation of conservation-oriented excavation projects in complex urban environments.

Methodology

Macro-modeling approach

Considering the desired level of precision and the required computation time, two modeling approaches available in ABAQUS can be employed to determine the deformation resistance of existing full-scale masonry structures: macro-modeling and micro-modeling. In macro-modeling approach, the masonry structure, composed of brick units and bonding mortar, is treated as a continuous homogeneous entity; micro-modeling approach discretizes the brick units and mortar into distinct components, where the brick units are simulated by continuous elements, while the mortar is simulated through carefully defined contact properties to investigate the mechanical behavior and failure mechanisms of masonry structures.

Macro-modeling approach considers the masonry structure—comprising blocks and mortar—as a continuous and homogeneous medium. To conduct macro-modeling analysis, it is essential to define an appropriate constitutive model for the material. The compressive constitutive model of masonry structures can adopt the Yang Weizhong model32. For the tensile stress–strain relationship, reference can be made to the constitutive behavior of concrete under tension: before reaching the peak tensile stress, the stress–strain relationship is linear; beyond the peak stress, the descending branch follows the typical curve used for concrete materials33,34, with the parameter set as αₜ = 2.0. The corresponding expression is as follows:

Compressive constitutive relationship:

\(\:{f}_{cm},\:{\epsilon}_{cm}\) - The peak stress and the corresponding peak strain on the compressive stress–strain curve of masonry, where:

\(\:{f}_{1}\) - Average compressive strength of masonry;

\(\:{f}_{2}\:\)- Average compressive strength of mortar;

Tensile constitutive relationship:

\(\:{f}_{tm},\:{\epsilon}_{tm}\) -The peak stress and its corresponding strain on the tensile stress–strain curve of masonry, where:

For brick masonry, the elastic modulus is given by \(\:{E}_{c}=370{f}_{cm}\sqrt{{f}_{cm}}\), and the Poisson’s ratio is \(\:\nu\:=0.15\). In the analysis of the structural loading, the compressive and tensile ultimate strains of the masonry can be taken as ten times the corresponding peak strain values35.

The Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model available in ABAQUS is employed for macro-modeling analysis. This model is designed to capture the nonlinear behavior of quasi-brittle materials, such as concrete, under complex loading conditions. It is particularly suitable for simulating the progressive development of microcracks, material degradation, and cracking in homogenized masonry structures during the loading process. The corresponding stress–strain relationship is defined in Fig. 1.

Specifically, the CDP model defines the compressive and tensile constitutive behavior of the material by inputting the following parameters: compressive stress–inelastic compressive strain \(\:({\sigma\:}_{c}-{\stackrel{\sim}{\epsilon}}_{c}^{in})\), compressive damage factor–inelastic strain \(\:({d}_{c}-{\stackrel{\sim}{\epsilon}}_{c}^{in})\), tensile stress–cracking strain \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{t}-{\stackrel{\sim}{\epsilon}}_{c}^{ck})\), and tensile stress–tensile damage factor \(\:{(\sigma\:}_{t}-{\stackrel{\sim}{\epsilon}}_{c}^{ck})\), along with the elastic modulus \(\:E\) and Poisson’s ratio \(\:\nu\:\). They are expressed as follows:

Therefore, when using the CDP model to analyze masonry structures, the damage factors Dc and Dt in the constitutive model of masonry must be converted into the corresponding CDP model damage parameters dc and dt based on the principle of energy equivalence36,37.

Micro-modeling approach

In micro-modeling analysis of masonry structures, the interaction between masonry units is defined using surface-based cohesive behavior, which characterizes the contact through interface bonding properties. This includes the normal strength and tangential shear strength at the interfaces between masonry and mortar. The traction–separation model is used to describe the failure behavior of the interface. In the initial linear elastic stage, the mechanical behavior can be expressed by Eq. (13).

In the equation, \(\:{t}_{n}\) is the normal tensile stress, \(\:{t}_{s},\: {t}_{t}\) are the first and the second shear stresses, respectively; \(\:{K}_{nn}\) is the normal stiffness, \(\:{K}_{ss}\) and \(\:{K}_{tt}\) are the first and the second shear stiffness, respectively (Fig. 2). \(\:{\delta}_{n}\) is the normal separation,\(\:{\delta}_{s}\) and \(\:{\delta}_{t}\) are the first and the second shear separation, respectively.

The contact stiffness can be calculated based on the elastic modulus of each constituent of masonry and the thickness of mortar (\(\:{h}_{m})\)38, as follows:

where \(\:{E}_{b},\:{E}_{m}\) are the elastic modulus of the block (b) and the mortar (m), respectively; \(\:{G}_{b},\:{G}_{m}\) are the shear modulus of the brick (b) and the mortar (m), respectively. Considering the fact that the modulus of the brick is less than the mortar, \(\:{E}_{b}=(5\sim20){E}_{m}\), so the stiffness in Eqs. (14, 15) can be simplified, for example:

In the micro-modeling analysis, the bricks are expanded by adding the mortar thickness, modelled as a series of continuum elements, while the interaction between the expanded bricks is defined using a traction-separation law. Therefore, the modulus of the expanded masonry structures should be modified to be equivalent to the original masonry assemblage of bricks and mortar. If the following equation is adopted39, the expression of the stiffness can be rewritten.

Where, \(\:{h}_{b}\), \(\:{h}_{m}\) are the thickness of brick unit and the mortar, respectively; n is the number of the brick layers and H is the total height. If the parameters between the brick and the mortar are assumed as \(\:{E}_{b}=(5\sim20){E}_{m}\), and \(\:{h}_{b}\approx\:5{h}_{m}\) for ordinary bricks, the expression of the stiffness can be further simplified as follows:

Equation 18 illustrates that the normal stiffness (also for the shear stiffness) has a close connection with the modulus of the masonry structure (E) and the thickness of the mortar (\(\:{h}_{m})\). Xia et al.40 advances a similar argument.

The initiation of damage and failure can be defined based on various criteria, such as maximum tensile stress, maximum shear stress, quadratic stress criterion, or mixed-mode fracture energy. According to the quadratic stress criterion, damage initiation at the interface occurs when the stress state satisfies the following Eq. (19).

Where \(\:{t}_{n}^{0},\:{t}_{s}^{0}\), and \(\:{t}_{t}^{0}\) are the peak normal tensile stress and shear stresses in directions s and t, respectively, under pure tension and shear conditions at interface separation. \(\:{t}_{n},\:{t}_{s}\) and \(\:{t}_{t}\) represent the normal stress and the shear stresses in directions s and t at the interface. The symbol \(\langle\:\rangle\) denotes the Macaulay bracket, indicating that compressive normal stress does not contribute to damage initiation.

As interface damage progressively evolves, the stiffness of the element degrades until the interface is fully separated and ceases to contribute to the structural response. In numerical models, multiple criteria can be used to determine complete failure, such as plastic displacement and fracture energy. The fracture energy is defined as Eq. (20).

Where \(\:{\stackrel{-}{\epsilon\:}}_{0}^{pl}\:\)and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{\epsilon\:}}_{f}^{pl}\) are the equivalent plastic strains at the onset of interface damage and at complete interface failure, respectively; L is the characteristic length of the finite element; \(\:{\stackrel{-}{u}}_{f}^{pl}\) is the equivalent plastic displacement at complete interface failure; and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{y}\) is the stress, which may refer to normal tensile stress or shear stress.

When both normal stress and tangential shear stress are present at the contact interface, the fracture energy is determined using the Benzeggagh–Kenane (BK) criterion, Eq. (21).

Where \(\:{G}_{n}^{c}\) and \(\:{G}_{s}^{c}\) are the fracture energies under pure normal tensile stress and pure shear stress, respectively. The total fracture energy is given by \(\:{G}_{T}={G}_{n}^{c}+{G}_{S}^{c}\), where \(\:{G}_{T}\) represents the sum of the fracture energies due to tangential shear stresses. For masonry structures, the parameter η can be taken as 2.041.

Fracture energy \(\:{G}_{f}\) is one of the key parameters in decoupled modeling analysis. A higher fracture energy indicates a greater resistance to crack propagation, allowing the structure to withstand larger external loads without failure. Under the same loading conditions, masonry structures with higher fracture energy exhibit fewer and narrower cracks. In contrast, lower fracture energy leads to easier crack initiation and propagation in masonry. Fracture energy can be calculated from the stress–displacement curve. The initial fracture energies corresponding to the onset of separation are denoted as \(\:{G}_{min,I}\) (normal direction) and \(\:{G}_{min,II}\) (shear direction), while the fracture energies corresponding to complete separation are denoted as \(\:{G}_{f,I}\) (normal) and \(\:{G}_{f,II}\) (shear). These values can be taken as \(\:{G}_{f,I}={5G}_{min,I}\) and \(\:{G}_{f,II}={10G}_{min,II}\)42,43.

Validation of FEM modeling

Model parameters

Zhejiang Customs Residential Annex (for simplicity, abbreviated as CRA) – A Municipal-Level Protected Historic Building in China. The structure was geometrically modeled as shown in Fig. 3. Certain simplifications were made in the model. The brick lintels at door and window openings were simplified as concrete lintels. The height of the brick foundation was set to 720 mm. The masonry units were assumed to behave elastically, while the interfaces between units were modeled using a traction–separation law. Damage initiation was defined based on the quadratic stress criterion, and complete interface failure was determined using the Benzeggagh–Kenane (BK) criterion. The Fig. 3 illustrates the trough-shaped soil displacement pattern induced by the adjacent excavation. \(\:H\) represents the excavation depth of the adjacent pit, with a value of 6.3 m.

According to experimental testing, the average compressive strength of the masonry in the CRA ranges from 7.1 to 10.5 MPa, while the mortar strength ranges from 2.1 to 7.5 MPa. Based on studies of masonry structures and standard30,31, the strength grades of the masonry and mortar are determined to be MU7.5 and M2.5, respectively. The average compressive strength of the masonry is \(\:{f}_{cm}\)=3 MPa and the average tensile strength is \(\:{f}_{tm}\)=0.377 MPa corresponding to a strain of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{t,m}\)=1.96 × 10−4. The values of the calculation parameters are listed in Table 1.

The stiffness \(\:{K}_{nn}({K}_{ss},{K}_{tt})\) is the slope of the line OA in Fig. 2, which can be employed to calculate the area of \(\:\varDelta\:OAB\),in linear elastic stage \(\:{S}_{\varDelta\:OAB}\) can be also expressed as:

Therefore, \(\:{K}_{nn}=\frac{E}{L}\),similar formula can be obtained for \(\:{K}_{ss},{K}_{tt}\).The length L is the characteristic length, with the value depending on the element geometry (i.e., mesh division) and formulation. It is a typical length of a line across an element for a first-order element, and a more precise definition of characteristic length can be found in Abaqus Analysis User’s Guide.

As masonry structures are assembled with large number of brick units, the mesh division for each brick unit determines the analysis efficiency and analysis accuracy. Investigations on mesh sensitivity on analysis accuracy for masonry structures modelled with micro-modeling approach in different commercial software44,45, illustrate that the numerical analyses have satisfactory results, if the number of the meshes in the length-direction is within 6 ~ 10, finer mesh division has limited improvement for analysis results. In this study, the characteristic length is 30 mm according to the feedback from the trial analysis with Abaqus for the same mesh division 8 × 4. The size of the brick is 240 (length)×60 (thickness) mm.

In the Table 1, the normal stiffness is defined a \(\:{K}_{n}=E/L\), with the tangential stiffness as \(\:{K}_{s}=G/L\), where \(\:G\) is the shear modulus, calculated from the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio, L=30 mm.

Damage evolution is defined using the fracture energy criterion based on the Benzeggagh–Kenane (BK) formulation. Based on the peak stress and strain values corresponding to MU7.5 masonry and M2.5 mortar, the calculated values are Eq. (23).

The foundation is modeled as an elastic body with a thickness of 60 mm (parametric analysis indicates that the foundation thickness has minimal influence on the results). The interface between the foundation and the building base is defined as a contact pair, with a friction coefficient of 0.4529. Deformations induced by the adjacent excavation, including settlement and horizontal displacement, are applied to the bottom boundary of the foundation model. The peak settlement is \(\:{\delta\:}_{v,max}=\)0.25%H, following a trough-shaped distribution30. While extensive research has been conducted on the magnitude and distribution of excavation-induced settlement outside the pit, studies on horizontal deformation are relatively limited. For engineering cases with trough-shaped settlement deformation, the horizontal deformation also exhibits a trough-shaped distribution, and the primary influence zones of both deformations are essentially the same. At the depth of shallow foundations, the magnitudes of both settlement and horizontal displacement are approximately equal to those at the ground surface24. Therefore, in the calculation, the horizontal soil displacement is assumed to follow the same distribution pattern as the soil settlement but with a smaller magnitude, and in the model, it is taken as 50% of the settlement value.

Model validation

Figure 4 presents the tensile damage contour plots (DAMAGET) of the structure under various ground settlements in the macro-modeling analysis. A higher DAMAGET value indicates more severe structural damage. As shown in Fig. 4, as the maximum soil displacement experienced by the building increases from 3 mm (\(\:\downarrow\:\)) + 1.5 mm \(\:(\to\:)\) to 7 mm (\(\:\downarrow\:\)) + 3.5 mm \(\:(\to\:)\), both the severity and extent of structural damage progressively increase (Table 2), the symbols (\(\:\downarrow\:\)) and \(\:(\to\:)\) represent the components of the vertical settlement and the lateral soil displacement. Based on the trough-shaped ground settlement pattern induced by the excavation, the soil displacement occurred around the building is primarily concentrated on the first doorway and window on the right side. Following the excavation, structural damage is also concentrated within this region, as indicated by the dashed box in Fig. 4.

It is generally considered that the structure is severely damaged when the damage coefficient (DAMAGET) exceeds 0.9. Therefore, when the soil displacement is less than 5 mm, the damage remains localized and the affected area is relatively limited. When the soil displacement exceeds 5 mm, penetration-type damage occurs, and a new damage area appears at multiple locations. To prevent damage to building structures, the combination of 5 mm vertical settlement and 2.5 mm horizontal soil displacement can be regarded as a threshold for the structural deformation tolerance. Prior to this threshold, severe damage occurs locally but does not extend through the entire section. Before this point, damage penetrates the full cross-section and continues to emerge at new locations. For clarity, the structural deformations shown in the contour plots in this study are magnified by a factor of 50.

Figure 5 shows the analysis results of the same building using the micro-modeling approach. Figure 5d presents the crack propagation contour (COPEN) corresponding to a soil displacement of 5.0 mm(\(\:\downarrow\:\)) + 2.5 mm (→). Figure 5f corresponds to a soil displacement of 7.0 mm (↓) + 3.5 mm (→). As shown in the Fig. 5, under the 5 mm soil displacement combination, the maximum crack width is 2.32 mm, while under the 7 mm soil displacement combination, it increases to 3.71 mm. When the soil displacement combination is less than 5 mm, the crack width remains relatively small.

Figures 4 and 5 indicate that the macro-modeling and micro-modeling approaches show good agreement in identifying vulnerable areas and assessing damage severity. In the macro-modeling analysis, regions with severe structural damage correspond to cracking areas in the micro-modeling results. As external soil displacement increases, both damage severity and crack width escalate. Therefore, for more complex analyses of a building’s deformation resistance, the macro-modeling approach can be effectively adopted.

Case study and results

Background and numerical modelling

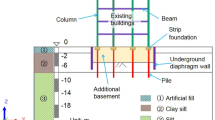

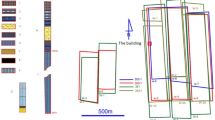

Former Site of Ningbo Post Office (NPO) – Zhejiang Provincial Cultural Heritage Building. The site was officially established in 1897, during the 23rd year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty, with an approved land area of 315.3 m2 and a total building area of 624.3 m2. The building is a masonry structure with exterior corridors, oriented west to east. Due to urban development needs, a new public building is planned to be constructed on the south side of the heritage structure (Fig. 6). Two design schemes for the basement are under consideration: a one-story and a two-story basement, corresponding to excavation depths of 6.3 m and 10.3 m, respectively. The retaining wall of the excavation will be approximately 10.15 m and 10.02 m away from the exterior walls of the two heritage buildings (Fig. 7).

NPO is a masonry structure, with exposed brickwork on the exterior and interior walls plastered with mortar and covered by decorative finishes. Experimental testing revealed significant variability in the strength of both bricks and mortar. The estimated mortar strength ranges from 2.1 to 7.7 MPa, and the average strength of the masonry units ranges from 10.5 to 16.25 MPa. Based on the average measured strengths of the masonry and mortar on site, and with reference to relevant masonry standard and research46, the strength grade of the masonry is determined to be MU7.5, and that of the mortar M2.5. The average compressive strength of the masonry is \(\:{f}_{cm}\)=3 MPa, and the average tensile strength is \(\:{f}_{tm}\)=0.377 MPa, corresponding to a strain of \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{t,m}\)=1.96 × 10−4.

Macro-modeling and micro-modeling are adopted simultaneously, with the macro-modeling approach used for the upper structure of the NPO and the micro-modeling approach for the lower part—stone plinths. The stone plinths are assumed to be homogeneous elastic bodies, and the interfaces between them are modeled as “hard contact,” allowing relative sliding. The contact surfaces are considered wet, with a friction coefficient of 0.6. The stone foundation rests on the subsoil, and the interaction between the foundation and the ground is modeled using a 60 mm thick homogeneous layer. According to the geotechnical report, the upper soil layer consists of approximately 3 m of fill containing brick fragments and rubble. The friction coefficient between the stone foundation and the subsoil is taken as 0.45.

The soil displacement induced by the adjacent foundation pit construction is applied to the lower of the subsoil. The maximum ground vertical settlement is assumed to be 0.15%H (for the two-story basement scheme, H = 10.3 m) and 0.25%H (for the one-story basement scheme, H = 6.3 m). The vertical settlement is assumed to follow a trough-shaped distribution30,31, while the lateral soil displacement at the burial depth of the strip-stone foundation is assumed to be consistent with the ground settlement, with its maximum value being 50% of the vertical settlement peak. Other parameters required for the damage plasticity model are taken as follows: dilation angle 30°, eccentricity 0.1, \(\:\frac{{f}_{b0}}{{f}_{c0}}=1.16\), K = 0.6667, and viscosity parameter 0.0005. Figure 8 shows the local mesh division of the former Ningbo Post Office site.

Numerical analysis results

Figure 9 shows the tensile damage contour maps (DAMAGET) of the heritage building adjacent to the one-story-basement foundation pit, with vertical settlement amplitudes \(\:{\delta\:}_{v,max}\) of 0.15%H, 0.20%H, and 0.25%H, and corresponding lateral soil displacement amplitudes equal to 50% of the vertical settlement values. As shown in the Fig. 9, both the damage coefficient and the extent of the damage increase with the external soil displacement. When the soil displacement is small, the damage coefficient remains low (DAMAGET = 048). However, when the maximum settlement reaches the recommended limit value of 0.25%H (\(\:{\delta\:}_{v,max}=15.75mm\)) as specified in the standard, severe damage (DAMAGET=0.93) occurs across nearly the entire section at the base of the arch, and noticeable displacement and misalignment of the foundation stone blocks can be observed (Fig. 9c). When the vertical settlement amplitude is 0.15%H, 0.20%H, and 0.25%H, the corresponding maximum settlement at the heritage building is 3.1 mm, 4.1 mm, and 5.2 mm, respectively — all within the mm range.

Figure 10 shows the tensile damage contour plots of the same heritage building subjected to differential ground settlements caused by the adjacent two-story basement pit excavation. The simulated vertical settlements are assumed to be 0.10%H, 0.15%H, and 0.20%H, with corresponding horizontal components at 50% of the vertical values (i.e., 0.05%H, 0.075%H, and 0.125%H).

Similar to the one-story-basement scheme, Fig. 10 illustrates that the severity and extent of damage increase with the increase of the amplitude of the soil settlement. Compared to the one-story-basement scheme, where only one bay of the protected building is directly affected by the excavation-induced soil settlement, the two-story-basement scheme results in a significantly wider settlement-affected zone, with nearly half of the structure located within the primary affected zone. Therefore, the extent and severity of damage are greater in the two-story scheme than in the one-story-basement scheme, for the identical amplitude of the soil settlement. For example, with a soil settlement combination of 0.2%H(↓) + 0.1%H(→), the one-story-basement scheme shows the damage localized at the base of a single arch, while the two-story-basement scheme exhibits multiple severely damaged areas, with the most critical damage occurring at the arch crown rather than the arch springing in the one-story-basement scheme. The shift in the location of severe damage can be attributed to the soil settlement pattern induced by excavation, which is modeled as a trough-shaped distribution. At the boundary between the primary influence zone (within 2 H) and the secondary influence zone (2 H to 4 H), there is a notable change in the displacement gradient. In the two-story-basement scheme, the crown thickness of the affected arch is smaller compared to that in the one-story-basement scheme, resulting in reduced deformation resistance. As a result, damage first occurs at the arch crown and tends to concentrate in this region.

The settlement amplitude of 0.15%H in Fig. 8 and 0.25%H in Fig. 7 correspond to the recommended soil settlement limits for the first-level and second-level safety grade foundation pits, respectively, as specified in the standard30,31. Numerical analysis reveals that when vertical settlement and lateral soil displacement are considered simultaneously—even with the lateral soil displacement limited to half the magnitude of the vertical settlement, localized severe damage may still occur in the structure if the soil displacement limits specified by the standard46 are adopted for design. However, if lateral soil displacement is ignored, no structural damage was observed (Fig. 11).

Figure 11 shows the contour of the tensile damage and contact open distance in the structure under the one-story-basement scheme. Only vertical settlement is taken into consideration in the analysis, with the amplitude increased to 0.25%H deliberately. The analysis results indicate the structure did not suffer degrading (DAMAGET = 0.0) when the lateral soil displacement is ignored, even if the vertical settlement is greater than the allowable value specified in the design standard. On the other hand, the separation behavior (COPEN) was still observed within the stone strip foundation, but the maximum separation is 1.4 mm, which is also notably smaller than the separation observed when the lateral soil movement is taken into account. It should be mentioned again that the interface between the upper masonry wall and the stone plinths is modeled as surfaced-based cohesive contact pair, implying the presence of adhesive interaction. In contrast, the contact between stone blocks within the foundation is modeled as a surface-to-surface “hard” contact pair, as the stones are stacked without mortar. Consequently, the stone block directly contacts with the masonry exhibit a distinct deformation pattern—bonded at the top face and separated at the bottom face.

To investigate the sensitivity of modelling technique for the interfaces between the upper masonry walls and the lower stone plinths, two additional FEM analyses were carried out: (a) The interfaces between the masonry wall and stone plinths, as well as between the stone plinths and the soil layer, are modeled as surfaced-based cohesive contact pairs; while the surfaces between stone units, being dry-laid, are assumed to be surface-to-surface “hard” contact pairs; (b) All interfaces are modeled as surfaced-to-surface “hard” contact pairs, including the interfaces between the masonry wall and stone foundation, the stone foundation and the soil layer, and the surfaces between stone units. In the analysis, the building is assumed to be adjacent to a foundation pit with a one-story basement. The vertical settlement amplitude is 0.25%H (H = 6.3 m), while the magnitude and distribution of lateral soil movement are assumed to be the same as those of the vertical settlement. Figure 12 shows that whether the masonry wall-stone plinths interface is modeled as surface-based cohesive contact pairs or not, it has minimal influence on the building’s deformation resistance assessment, as the tensile damage DMAGET has the identical numerical values 0.93, and the contact open distance (COPEN) only has a minor difference (3.0 mm vs. 3.3 mm).

Optimization of deep foundation pit engineering design

The previous sections have provided a detailed introduction to the macro-modeling approach, and based on this method, the mechanical response of NPO building during foundation pit excavation has been analyzed. The results indicate that the arch zone is most prone to damage due to stress concentration. Based on the simulation results and on-site tests, a graded control standard is proposed for the deep foundation pit design, which is adjacent to the NPO building:

-

(a)

Safety Limit: Soil displacement should not exceed 5 mm for the one-story-basement scheme or 10 mm for the two-story-basement scheme, in order to prevent through-cracking and ensure structural integrity.

-

(b)

Damage Control Threshold: Soil displacement should be limited to 3.5 mm for the one-story-basement and 7 mm for the two-story-basement scheme, aiming to restrict the development of localized cracking.

-

(c)

Early Warning Trigger: When vertical settlement or lateral soil displacement reaches 3.5 mm, emergency mitigation measures should be promptly initiated to prevent further structural degradation.

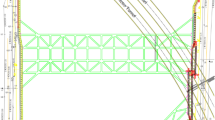

Based on the threshold values proposed above, predictive design analyses were conducted for both the One-story-basement and Two-story-basement excavation schemes. The predicted settlement values at the location of the heritage building are provided in Table 3 and Fig. 13. These predictions are then compared against the control thresholds to determine whether the design meets the required standards.

To ensure the safety of the foundation pit and adjacent heritage buildings, the construction team adopted the “TRD cement-soil mixing wall + H-beam reinforcement + one-layer concrete horizontal bracing + alternative bay construction” method in the actual engineering protection scheme. During construction, a rigorous execution plan was implemented, encompassing earthwork excavation sequencing, dewatering measures, and monitoring protocols. Figure 14 is the monitoring results of the deep soil displacement during critical periods. The entire foundation pit engineering construction period spans 90 days, commencing with earth excavation and concluding upon completion of the basement slab. Though two abrupt displacement changes were detected during specific time intervals and the final soil displacement is somewhat greater than the theoretical value, but the measured settlements (3.4–3.7 mm) and lateral soil displacement (2.46–2.83 mm) of both heritage buildings (NPO and CRC) were successfully maintained within the predetermined safety thresholds.

During one year of on-site structural deformation monitoring, the width of the original cracks in the structures, which located at the vault- the most prone area for cracking, has increased, but less than 1 mm (Fig. 15). On the other hand, newly localized micro-cracking was observed, which locates at the vault, with the actual damage patterns exhibiting excellent correlation with the predicted failure modes (specifically at vault arches and foundation interfaces, as shown in Fig. 16) from the numerical analysis. These findings demonstrate that: (1) the proposed control criteria effectively ensure the safety of heritage structures; (2) historic buildings exhibit significantly higher sensitivity to millimeter-scale deformations compared to modern constructions; (3) the H-beam retrieval process requires optimization (e.g., through grouting integration) with strict vibration control (≤ 0.27 mm/s). Through this engineering practice, we have demonstrated that the implementation of an integrated methodology incorporating high-fidelity numerical simulations, real-time monitoring throughout construction phases, and coordinated multi-measure control strategies enables precise deformation management for foundation pits adjacent to culturally significant structures. These findings provide empirical validation of the efficacy of the “simulation-monitoring-support” tripartite system in safeguarding heritage buildings during nearby excavation activities.

Conclusions

Focusing on the deformation compatibility issues between deep foundation pits and neighboring cultural relics in urban areas, this study develops a novel assessment framework for structural deformation resistance utilizing numerical modeling techniques. Based on representative cases such as the NPO heritage building, the study demonstrates the progressive deterioration mechanism caused by soil displacement in cultural relic buildings. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) As a critical preparatory work for excavation design, the deformation capacity thresholds of historical masonry buildings can be determined through computational analysis. The identified cracking criterion enables scientifically-grounded adjustments to existing Standard specifications, overcoming the dichotomy between unnecessary over-protection and potential structural damage in conventional practice.

(2) Macro- and micro-scale modeling approaches in ABAQUS provide complementary capabilities for evaluating the deformation resistance of masonry structures. For buildings with complex geometries (i.e., arched structure), macro-modeling employing homogenized constitutive relationships demonstrates superior performance in capturing global failure patterns and computational efficiency, whereas micro-modeling becomes essential when investigating masonry interface damage mechanisms. The proposed hierarchical modeling protocol enables targeted analysis matching different conservation engineering needs. Material parameters should be calibrated using field-measured data.

(3) Numerical analysis of the heritage buildings validates that the code-prescribed soil displacement thresholds serve as upper-bound advisory limits for mitigating heritage structure damage. When considering horizontal soil displacement impacts, research indicates a 30% reduction from code limits is warranted, achieving 70% of the specified threshold through case study calibration.

(4) To mitigate material degradation (e.g., 25% mortar strength reduction), reversible measures-temporary shoring, grout injection, and vibration monitoring—are implemented alongside checkerboard excavation to control deformation. A systematic “evaluation-optimization-conservation” approach ensures dynamic balance between heritage preservation and excavation engineering.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Masini, L., Gaudio, D., Rampello, S. & Romani, E. Observed performance of a deep excavation in the historical center of Rome. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 147, 05020015 (2021).

Lazzari, M., Geraldi, E., Lapenna, V. & Loperte, A. Natural hazards vs human impact: an integrated methodological approach in Geomorphological risk assessment on the tursi historical site, Southern Italy. Landslides 3, 275–287 (2006).

Huang Maosong, Wang, W. Zheng Gang. A review of recent advances in the underground engineering and deep excavations in soft soils. China Civ. Eng. J. 45, 146–161 (2012).

Zhang, D. M., Xie, X. C., Li, Z. L. & Zhang, J. Simplified analysis method for predicting the influence of deep excavation on existing tunnels. Comput. Geotech. 121, 103477 (2020).

Yan, N. et al. Study on the deformation characteristics of diaphragm walls in deep excavations within the Ningbo soft soil region. Sci. Rep. 15, 15036 (2025).

Son, M. & Cording, E. J. Responses of buildings with different structural types to Excavation-Induced ground settlements. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 137, 323–333 (2011).

Ali Soomro, M., Liu, K., Ali Mangnejo, D. & Mangi, N. Effects of twin excavations with different construction sequence on a brick masonry wall: 3D finite element approach. Structures 41, 866–886 (2022).

Kog, Y. C. Excavation-Induced settlement and Tilt of a 3-Story Building. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 31, 04016080 (2017).

Yuan, B. et al. Study on the interaction between pile and soil under lateral load in coral sand. Geomech. Energy Environ. 42, 100674 (2025).

Zheng, C., Franza, A. & Jimenez, R. Analysis of floating and end-bearing pile foundations affected by deep-excavations. Comput. Geotech. 153, 105075 (2023).

HU, G. et al. Research on influence laws of vibration by rotary drilling during foundation excavation on surrounding buildings and the environment. Ind. Constr. 54, 226–233 (2024).

Wang, S. & Zhu, S. Vibration impact of rock excavation on nearby sensitive buildings: an assessment framework. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 163, 107508 (2022).

WAN, Y. et al. Measured analysis of the vibration of the surrounding environment of the foundation pit by Heavy-Duty vehicles on the construction site in soft soil area. SOUTH. CHINA J. Seismol. 44, 128–138 (2024).

Yuan, B. et al. Dynamic behavior and deformation of calcareous sand under Cyclic loading. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 199, 109730 (2025).

Pathak, R., Saini, A., Wadhwa, A., Sharma, H. & Sangwan, D. An object detection approach for detecting damages in heritage sites using 3-D point clouds and 2-D visual data. J. Cult. Herit. 48, 74–82 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. An Uncertainty-Aware Crowd-AI collaboration system for cultural heritage damage assessment. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 9, 1515–1529 (2022).

Yu, Q., Yang, X., Wu, Y. & Fang, K. Adaptability assessment of the Enning road heritage district in China based on GA-BP neural network. Sci. Rep. 15, 15370 (2025).

Frasca, F. et al. Assessing microclimate thresholds for heritage preventive conservation to achieve sustainable and energy efficiency goals in a changing climate. Sci. Rep. 14, 18707 (2024).

Seo, H. R–C–C fusion classifier for automatic damage detection of heritage Building using 3D laser scanning. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 15, 927–941 (2025).

Afifi, H. A. M., Mansour, M. M. A., Hassan, A. G. A. I. & Salem, M. Z. M. Biodeterioration effects of three Aspergillus species on stucco supported on a wooden panel modeled from Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay Mausoleum, Egypt. Sci. Rep. 13, 15241 (2023).

Li, Y., Deng, Y., Li, A. & Jia, Y. Improving seismic performance for inclined historical Building by using external protection structure: case study of Yingxian wooden pagoda, China. J. Build. Eng. 96, 110381 (2024).

Liu, N. et al. Estimation of Building damage caused by adjacent deep excavation in clay. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. - Geotech. Eng. 174, 430–445 (2020).

Ertürk Atmaca, E., Genç, A. F., Altunişik, A. C., Günaydin, M. & Sevim, B. Numerical simulation of severe damage to a historical masonry Building by soil settlement. Buildings 13, 1973 (2023).

Ou, C. Y., Teng, F. & Li, C. W. A simplified Estimation of excavation-induced ground movements for adjacent Building damage potential assessment. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 106, 103561 (2020).

Yuan, B. et al. Effects of particle size on properties of engineering muck-based geopolymers: optimization through Sieving treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 492, 142967 (2025).

Son, M. & Cording, E. J. Evaluation of Building stiffness for Building response analysis to Excavation-Induced ground movements. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 133, 995–1002 (2007).

Burd, H. J., Yiu, W. N., Acikgoz, S. & Martin, C. M. Soil-foundation interaction model for the assessment of tunnelling-induced damage to masonry buildings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 119, 104208 (2022).

Schuster, M., Kung, G. T. C., Juang, C. H. & Hashash, Y. M. A. Simplified model for evaluating damage potential of buildings adjacent to a braced excavation. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 135, 1823–1835 (2009).

Prosperi, A., Longo, M., Korswagen, P. A., Korff, M. & Rots, J. G. Sensitivity modelling with objective damage assessment of unreinforced masonry façades undergoing different subsidence settlement patterns. Eng. Struct. 286, 116113 (2023).

Shanghai Housing and Urban-Rural Development Management Commission. Technical Standard for Excavation Engineering: DG/TJ08-61-2018 (Tongji University, 2018).

The National Standards Compilation Group of Peoples Republic of China. GB50007–2011 Code for design building foundation (China Architecture and Building, 2011).

Yang Weizhong. Constitutive relationship model for masonry materials in compression. Build. Struct. https://doi.org/10.19701/j.jzjg.2008.10.027 (2008).

Nina, Z. H. E. N. G. et al. Pseudo-static test study on seismic behavior of masonry wall restrained by core-tie-columns. China Civ. Eng. J. 46, 202–207 (2013).

Cheng Haoran & Jing Denghu. Typical diseases and pre-warning analysis on overall collapse of the City wall leaning against mountain in Nanjing. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 35, 143–152 (2023).

Zhang Wangxi, D. & Lianrui, L. Liu jie. Dynamic elastic-plastic time-history analysis of masonry structure based on ABAQUS. Build. Struct. 46, 64–70 (2016).

Lubliner, J., Oliver, J., Oller, S. & Oñate, E. A plastic-damage model for concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 25, 299–326 (1989).

Lee, J. & Fenves, G. L. Plastic-Damage model for Cyclic loading of concrete structures. J. Eng. Mech. 124, 892–900 (1998).

Lourenço, P. B. & Rots, J. G. Multisurface interface model for analysis of masonry structures. J. Eng. Mech. 123, 660–668 (1997).

Abdulla, K. F., Cunningham, L. S. & Gillie, M. Simulating masonry wall behaviour using a simplified micro-model approach. Eng. Struct. 151, 349–365 (2017).

Xia, Q., Liu, T., Li, Y., Xiong, Y. & Ma, Y. Simulation and multi-dimensional damage evolution analysis of detailed micro-model representing ancient brick masonry compressive behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 457, 139410 (2024).

Soomro, M. A., Mangnejo, D. A., Saand, A. & Hong, Y. Responses of a masonry façade to multi-propped deep excavation-induced ground deformations: 3D numerical parametric study. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 26, 5983–6011 (2022).

Dolatshahi, K. M. & Aref, A. J. Multi-directional response of unreinforced masonry walls: experimental and computational investigations. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 45, 1427–1449 (2016).

Benzeggagh, M. L. & Kenane, M. Measurement of mixed-mode delamination fracture toughness of unidirectional glass/epoxy composites with mixed-mode bending apparatus. Compos. Sci. Technol. 56, 439–449 (1996).

Pulatsu, B., Erdogmus, E., Lourenço, P. B., Lemos, J. V. & Tuncay, K. Simulation of the in-plane structural behavior of unreinforced masonry walls and buildings using DEM. Structures 27, 2274–2287 (2020).

Chaimae, K., Younes, E. R., Ouadia, M. & Shamass, R. Finite element simulation of masonry wall behavior: exploring various brick bonds and load conditions. Structures 77, 109089 (2025).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rual. Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for design of masonry structures: GB 50003 – 2011 (China Architecture and Building, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ningbo Lao Waitan North Shore Construction and Investment Co., Ltd. and the Ningbo Cultural Heritage Preservation and Management Institute for their support in on-site surveys, assessments, and preventive conservation efforts. We also appreciate Ningbo Ningda Foundation Treatment Technology Co., Ltd., the Geotechnical Institute of Ningbo Architectural Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd., Ningbo Huadong Nuclear Industry Survey and Design Group Co., Ltd., and Zhejiang Heli Building Special Technology Co., Ltd. for providing the foundation pit design, construction monitoring, and heritage building monitoring reports.

Funding

This research was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Cultural Relics Protection Science and Technology Project (2024014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guangbin WANG contributed to conceptualization, writing and funding acquisition. Qiqun LI developed the support system and optimized excavation parameters. Changyong SONG conducted numerical modeling and drafted the manuscript. Jiang CHEN and Yao YAO performed field monitoring and data validation, and made crucial supplements and improvements to the manuscript during the revision stage. Liujun YANG led the numerical sensitivity analysis and terminology standardization. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Li, Q., Song, C. et al. Preventive conservation engineering practice based on deformation resistance capacity evaluation of heritage buildings. Sci Rep 15, 40256 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23996-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23996-8