Abstract

Frailty, a common geriatric syndrome, is characterized by diminished physiological reserves and heightens the risk of adverse health events, including falls, hospitalizations, and mortality. Prevalence of frailty is increasing in populations by age. Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) plays a pivotal role in energy metabolism, inflammation, DNA repair, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. Despite numerous studies investigating the functions of SIRT6, the role of its genetic variations in frailty remains poorly understood. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between SIRT6 SNP rs117385980 (C > T) and frailty syndrome. This study included samples from a cohort of older adults in Birjand, Iran, comprising 227 subjects, aged 60–90 years divided according to frailty status. Allele and genotype frequencies of the SIRT6 rs117385980 variant were analyzed in all participants. Results of the study indicated the increased presence of non-frail and pre-frail individuals compared to the frail group. Among individuals aged 60–69, 70–79, and 80–90 years, the frequency of the heterozygous CT genotype demonstrated a declining trend with advancing age (p = 0.07). Our findings suggest that the presence of rs117385980 T allele was decreased in older subjects but increased with robustness suggesting a diverse effect. Further studies with larger sample sizes and Dates of death data are warranted to confirm these preliminary findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the world’s population ages, frailty is poised to emerge as a major public health concern in the coming decades1. Frailty, a common geriatric syndrome, is linked to aging and leading to decreased health and functional capacity in the elderly. Frailty is characterized by diminished physiological reserves and impaired organ function, rendering individuals more vulnerable to acute stressors and increasing their risk of adverse health outcomes including falls, hospitalizations, and mortality2. Fried et al. established one of the most prominent prevailing standards for frailty identification. A person is categorized as frail if they fulfill three or more of the five specified criteria, which include weakness, weight loss, slowness, low activity, and exhaustion3.

Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6), a member of the mammalian sirtuin family, is primarily localized in the cell nucleus and possesses mono-ADP-ribosylation, NAD+-dependent deacetylase, and defatty-acylation activities. As a key regulator of cellular metabolism, particularly beta-oxidation in the liver, SIRT6 is involved in a wide range of biological processes such as energy metabolism, regulation of inflammatory responses, DNA repair, oxidative stress, and fibrosis4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

SIRT6 exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through the suppression of c-JUN-dependent transcription of pro-inflammatory genes, including MCP-1 and IL-67. This anti-inflammatory role of SIRT6 is further supported by the finding that the downregulation of SIRT6 is implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammation through its association with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules8. Moreover, the NF-κB pathway, a pivotal regulator of immunity and inflammation, is negatively regulated by SIRT69. The expression of antioxidant genes can be modulated by SIRT6, thus safeguarding cells from oxidative stress-induced damage5.

SIRT6 overexpression mitigated frailty in B6 mice through mechanisms involving upregulated hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, enhanced de novo NAD + biosynthesis, and stimulated glycerol release from adipose tissue. These findings suggested that SIRT6 plays a pivotal role in maintaining energy homeostasis, thereby delaying the onset of frailty in aging10.

Serum SIRT6 levels were significantly lower in individuals with frailty compared to robust older adults. decreased serum SIRT6 levels was independently associated with a higher risk of developing frailty11.

The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs117385980 (C > T) is a stop gained variant within the exon 2 of SIRT6 gene, has been implicated in longevity and healthy aging. Previous studies have revealed an inverse correlation between the T allele of SNP rs117385980 and increased lifespan in a Finnish male cohort12. Given the potential of this SNP in modulating SIRT6 gene expression or protein structure, and consequently its function, and considering some shared characteristics of aging and frailty, we hypothesized a link between rs117385980 and frailty syndrome. The present study aims to test this hypothesis.

Methods

Study population

This case-control study was embedded within the baseline data of the Birjand Longitudinal Aging Study (BLAS). The study population consisted of a subset of elderly individuals from (BLAS), born between 1928 and 1958 in Birjand, Iran. BLAS is an ongoing community-based prospective cohort study of individuals aged 60 years and older residing in Birjand County, Iran. The sampling strategy for BLAS employed a multi-stage stratified random sampling method with age weightingThe study collected extensive data, including sociodemographic information, medical history, lifestyle factors, activities of daily living, cognitive function, and biological samples17. Our study sample was randomly selected from 961 subjects who participated in the first phase of BLAS and had whole blood samples available in the − 80 °C biobank. Participants were categorized into three age groups (60–69 years, 70–79 years, and 80 years and older). The final sample consisted of 227 individuals aged 60–90 years, who were further categorized based on frailty status: frail (n = 39), pre-frail (n = 150), and robust (n = 38).

The inclusion criteria for BLAS participants included age ≥ 60 years, willingness to participate, and ability to communicate. Exclusion criteria included being bedridden or having a life expectancy of less than 6 months (based on clinician judgment). For this particular study, sampling was performed randomly from the total BLAS participants who had DNA samples available in the biobank (from 1020 samples with a frailty prevalence of 17.85%, we selected approximately 22% of subjects).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Phase I: Ir.bums.REC.1397.54; Phase II: IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1399.071). Prior to the original data collection, all participants and/or their legal guardians provided written informed consent. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Demographic data, including age, sex, and years of education, were collected through structured interviews conducted by trained researchers. Anthropometric measurements were obtained following the NHANES III protocol. Weight was measured using a calibrated Seca instrument (Germany) with an accuracy of 0.5 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the square of height (m²), as defined by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III Body Measurements (Anthropometry).

Physical Performance Measurements: participants’ gait speed was measured by completing a 4.57-meter walk test three times, with the highest recorded speed used for analysis. Handgrip strength was measured six times (three per hand) using a SAEHAN dynamometer (Seoul, Korea), with the maximum value recorded as the participant’s grip strength.

Frailty assessment

Frailty was evaluated according to the Fried frailty phenotype criteria (3) using the following five components: Slow gait speed: Defined as the slowest 20% (lowest quintile) of the population based on gender and height. Specifically, the cutoffs were: time to walk 4.57 m ≥ 7 s for men with height ≤ 173 cm and women with height ≤ 159 cm.

Weak handgrip strength: Defined as the lowest 20% (lowest quintile) based on gender and body mass index (BMI) quintiles. Cutoffs were applied according to standard criteria from the Fried study (e.g., for men: ≤29 kg for BMI ≤ 24, ≤30 kg for BMI 24.1–26, ≤ 30 kg for BMI 26.1–28, and ≤ 32 kg for BMI > 28; for women: ≤17 kg for BMI ≤ 23, ≤17.3 kg for BMI 23.1–26, ≤ 18 kg for BMI 26.1–29, and ≤ 21 kg for BMI > 29).

Low physical activity: Defined as weekly energy expenditure < 383 kcal/week for men or < 270 kcal/week for women, assessed via the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam Physical Activity Questionnaire (LAPAQ) and converted to kcal using MET values.

Exhaustion: Identified using two items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D): “I felt that everything I did was an effort” and “I could not get going.” A positive response to either question for most of the time in the past week met the criteria for exhaustion.

Unintentional weight loss: Defined as self- or informant-reported loss of ≥ 4.5 kg (or ≥ 5% of body weight) over the past year.

Participants with ≥ 3 criteria were classified as frail; those with 1–2 criteria were prefrail.Comorbidity Data: Chronic diseases were verified through: Self- or informant-reported clinician-diagnosed conditions and Cross-checking electronic health records.

Sample collection

Fasting whole blood samples were collected and stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction.

Laboratory procedures

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using a commercial DNA extraction kit (Roje, Iran) following the manufacturer’s protocol. To quantify and assess the purity of the extracted DNA samples, a Nanodrop spectrophotometer was employed. the absorbance at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nanometers was measured. The 260/280 absorbance ratio was calculated to evaluate sample purity with respect to protein and other contaminants.

To detect the variant of interest in samples, PCR-RFLP technique was employed. Primers were designed and subsequently synthesized as follow: The forward primer sequence was 5’-CTCAGGCAAGACAGGGACAG-3’ and the reverse primer sequence was 5’-ATGAGGTGAGTGGAATGCTGG-3’. These primers were used for PCR amplification of the target fragment. The primers were made by Nedayefan, Iran company, https://nedayefan.com.

The total PCR reaction volume was 20 µL. The reaction mixture contained 2 µL of template DNA, 0.5 µL of each primer, 8 µL of master mix, and 9 µL of dH₂O. PCR amplification was performed using the following cycling parameters: an initial denaturation step of 95 °C for 5 min was followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at a highly specific temperature of 63 °C for 50 s, and extension at 75 °C for 1 min. These conditions were found to be optimal for efficient amplification of the target fragment. A 5-minute final extension at 75 °C was included for final extension of all amplified DNA fragments. To verify the amplification of the expected 661 bp fragment, the PCR amplicons were resolved on a 2% agarose gel.

The restriction enzyme digestion was performed at 37 °C for 16 h using 0.3 µL of BsuRI (HaeIII) restriction enzyme (Thermo Scientific company, Lithuania), 1 µL of Buffer R, 1.7 µL of dH2O, and 7 µL of PCR product. Following the restriction enzyme digestion, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% agarose gel to visualize the resulting DNA fragments. Amplicons containing the wild-type allele were digested to produce 43 bp, 161 bp, 216 bp, and 241 bp fragments; those containing the mutant allele yielded 43 bp, 216 bp, and a 402 bp fragment. A heterozygous CT genotype was inferred when both a 402 bp and a 161 bp fragment were visualized on the gel. The absence of the 402 bp fragment was indicative of a homozygous wild-type CC genotype, whereas the absence of the 161 bp fragment suggested a homozygous mutant TT genotype.

To further validate the genotyping results obtained from PCR-RFLP, Sanger sequencing was performed on three purposively selected samples representing different genotypic groups, including two homozygous wild-type (CC) and one heterozygous (CT) sample, by NiyaGene Human Genetics Company, Iran. The results confirmed complete concordance with the PCR-RFLP findings (Fig. 1).

PCR-RFLP results confirmation using Sanger Sequincing: The figure illustrates the validation of SIRT6 SNP rs117385980 (C > T) genotyping results obtained by Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) against Sanger sequencing. Panels (a), (b), and (c): Sanger sequencing chromatograms confirming selected genotypic groups: Panel (a): Shows the heterozygous CT genotype (sample Code: 1707) with overlapping blue (C) and red (T) peaks at the SNP position. Panels (b) and (c): Show the homozygous wild-type CC genotype (samples Code: 1414 and 1694), where only the blue peak (C) is present at the SNP position. Panel (d): Representative PCR-RFLP results separated on a 4% agarose gel. The target fragment was 661 bp prior to restriction digestion. Digestion was performed with the BsuRI (HaeIII) restriction enzyme: CC Genotype (Wild-Type): The amplicon is digested, yielding observable fragments of 241 bp, 216 bp, and 161 bp. (the 43 bp fragment is not discernible on this gel). CT Genotype (Heterozygous): Both the digested wild-type fragments (e.g., 161 bp) and the 402 bp fragment (indicative of the undigested mutant T allele) are visualized. 1 kb: Molecular weight marker (Ladder).

Statistical analysis

chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were employed using STATA statistical software to compare the allelic and genotypic frequencies of the target SNP across various phenotypic groups including frailty, age, gender, diabetes, and hypertension.

As we did not have any data in some of box we categorized the frail and non-frail population into a one group and then conducted the univariate and multiple logistic regression models. We utilize the backward approach with threshold of P < 0.2 for developing the final multiple logistic regression model. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was checked for the data of genotypes.

Results

The demographic data and clinical characteristics of individuals in different groups are given in the Table 1.

Genotype distributions (heterozygotes) and minor allele frequencies (MAF) for the SIRT6 rs117385980 variant are presented in Table 2.

The T allele was absent in the frail group (0%) and observed at a low frequency in the non-frail group (2.13%), although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.36) (Table 3).

On the other hand, the frequency of the T allele was numerically lower in the 80–90 years age group (0%) compared to the 60–69 (1.39%) and 70–79 (4.65%) age groups (p = 0.073) (Table 4). The trend was further highlighted by the comparison between the 70–79 and 80–90 age groups, where the Fisher’s exact test revealed a p-value of 0.06 and an odds ratio of 3.9.

In addition to the lack of a significant association between the minor allele frequency and frailty, no significant correlation was observed between the T allele frequency of rs117385980 and sex, diabetes, or hypertension in this study (Table 5).

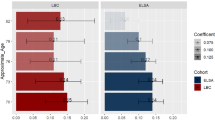

We performed multiple logistic regression models to assess the relationship between the T allele of rs117385980 and frailty (non-frail vs. frail status) while adjusting for potential confounders (Table 6).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the association between genetic variant within SIRT6 gene with frailty syndrome in Birjand elderly cohort. Although our findings did not reveal a significant association, a potential inverse association was observed between T allele of rs117385980 variant and individuals aged 80 years and over. The T allele was observed among individuals aged 60 to 80 years, but was absent in those older than 80.

Frailty prevalence in our Birjand cohort (17.18% frail) exceeded rates in prior Iranian studies, including a 14.3% rate using the Frailty Index (FI) in southwestern Iran18 and a 9.5% rate using the Frailty Phenotype (FP) in a larger Birjand sample19. This divergence reflects methodological differences: the FI quantifies cumulative health deficits, while the FP emphasizes physical decline, potentially explaining our cohort’s higher FP-based rate. Notably, U.S. studies report frailty prevalences of 5–17% in older adults20, with lower rates often attributed to robust healthcare systems. The elevated rate in Birjand may reflect regional disparities in healthcare access or socioeconomic factors—for instance, limited geriatric care in rural Iran could exacerbate physical decline, consistent with our FP-based assessment.

This finding is further supported by a similar study conducted in a Finnish male cohort, which demonstrated an inverse association between the T allele and a group of healthy men with a mean age of 83 years (p = 0.074)12. The SNP rs117385980 (C > T) has been previously linked to longevity in this Finnish male cohort, where heterozygosity was observed in 1/42 long-lived men (aged 77+) compared to 9/92 men who died younger (mean age 66)12. While this suggests an age-dependent survival disadvantage for carriers, the Finnish study’s male-only design precluded sex-specific analyses. Our study expands this paradigm by examining both sexes in the Birjand elderly population, revealing heterozygosity in 3.7% of males (4/106) and 3.2% of females (4/121), with no significant sex difference (p = 0.87). This challenges the assumption of inherent sex specificity and underscores the need for sex-balanced cohorts in genetic longevity research. Strikingly, both cohorts exhibited a marked decline in heterozygosity at advanced ages: Finnish men aged 77+ (1/42, 2.4%) and Birjand participants aged 80–90 (0/40). This age-dependent reduction may reflect antagonistic pleiotropy, where genetic variants beneficial in early life become detrimental in old age.

Furthermore, another study examining the genotype of 1192 participants from four groups, including the Iowa population, revealed that individuals with the CC or CT genotype of SIRT6 gene rs107251 exhibited a greater than 5-year survival rate compared to those with the TT genotype13. In another study of 503 individuals from Bama County, China—a region renowned for its high life expectancy rates compared to other Chinese counties—the C allele at rs350846 of the SIRT6 gene was associated with longevity14. However, another study on 1462 individuals from Hainan Island, China, investigating five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the SIRT6 gene (rs350852, rs350844, rs352493, rs4807546, and rs3760905) found no significant association with longevity15. Studies should be designed to investigate the role of these polymorphisms in the expression or function of SIRT6.

Extensive research has delved into the intricate relationship between the SIRT6 gene and genomic/epigenetic stability, with profound implications for lifespan. A comprehensive review by Korotkov et al. (2022) provides a thorough overview of this subject21. Their findings reveal that upregulation of SIRT6 significantly extends the lifespan of both male and female mice by 27% and 15%, respectively10. Conversely, the D63H mutation in SIRT6 has been linked to early embryonic lethality22.

SIRT6 protein functions as a protective agent against the age-related decline in DNA repair mechanisms. By stimulating both base excision repair (BER) and nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathways, SIRT6 mitigates the effects of aging. The deacetylation of DDB2 by SIRT6 is a pivotal mechanism underlying this protective function23,24. Furthermore, this protein effectively safeguards cells against DNA double-strand breaks by activating the homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathways. Notably, this mechanism can decelerate the aging process in long-lived species and extend cellular lifespan25. Moreover, SIRT6 plays a pivotal role in coordinating the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. Following deacetylation by SIRT1, SIRT6 acts as a scaffold by binding to phosphorylated γH2AX, thereby recruiting additional repair proteins to the damage site26. SIRT6 modulates the activity of DNA repair enzymes via mechanisms including deacetylation and ADP-ribosylation. For example, SIRT6-mediated deacetylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 is a critical step for subsequent PARP1-dependent ribosylation of H3 at serine 10, which is essential for effective DNA repair27.

SIRT6 functions as a genomic guardian against oxidative stress-induced damage. By activating DNA repair mechanisms, particularly through collaboration with PARP1 and MYH, it contributes to maintaining genomic integrity. MYH plays a crucial role in repairing oxidative DNA damage, especially in telomeres, and is recruited to the damage site in conjunction with SIRT6 and the Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 (9-1-1) complex. SIRT6 acts as an initial damage sensor, facilitating the recruitment of MYH and Hus1 to the lesion site. The interplay among these proteins is essential for preserving telomere integrity and preventing cellular senescence28,29,30.

Studies have demonstrated that SIRT6 plays a pivotal role in regulating the expression of LINE1 retrotransposons. SIRT6-deficient mice exhibit increased LINE1 activity, shortened lifespan, and growth defects. The underlying molecular mechanism is likely linked to the epigenetic regulation of LINE1 elements by SIRT6. Specifically, SIRT6 suppresses LINE1 transcription and retrotransposition by modifying the KAP1 protein31,32.

A separate study revealed a novel protective mechanism for SIRT6 in ligamentum flavum cells. SIRT6 appears to prevent cellular senescence by regulating telomerase activity. Overexpression of SIRT6 was associated with increased telomerase activity and decreased senescence markers33.

While the (possibility) of an inverse association between the presence of T allele and increased longevity in Birjand elderly individuals cannot be ruled out, more conclusive evidence is needed. A larger-scale analysis, incorporating mortality and lifespan data, is required to draw definitive conclusions. Unfortunately, complete Dates of death data for the Birjand Longitudinal Aging Study (BLAS) is currently unavailable. Another limitation of this study was the unequal distribution of participants across the frailty phenotype groups. The pre-frail group was larger than the frail and robust groups, constituting approximately two-thirds of the total sample. This imbalance may have limited our ability to detect significant differences between the frail and robust groups. Future studies with a more balanced distribution of participants across the frailty spectrum are needed to confirm these findings.

A notable aspect of frailty research is the diversity of assessment methods employed. While the (Physical Frailty Phenotype) and (Frailty Index/Deficit Accumulation) models are commonly utilized, their inherent differences in conceptualization and measurement can yield varying results. This diversity presents an opportunity for future studies to adopt a multi-method approach, enhancing the comprehensiveness and robustness of findings.

Furthermore, it is important to consider the statistical power of this study. The sample size was determined by the availability of samples in the BLAS biobank. While it was sufficient to detect trends and effect sizes similar to those reported in prior literature (12), the power to detect smaller associations was limited, particularly for a variant with such a low minor allele frequency. The consistency of the observed directional trends with previous findings and the application of multiple statistical models adjusting for key confounders strengthen the robustness of our analyses. Future studies with larger, prospectively powered cohorts are needed to confirm these preliminary associations.

Conclusions

This exploratory study did not find a statistically significant association between the SIRT6 rs117385980 variant and frailty syndrome. However, a non-significant trend was observed, suggesting a potential inverse relationship between the T allele and advanced age, which may imply a role in longevity. These findings should be interpreted with caution due to the exploratory nature of the analysis. Further validation in larger, prospective cohorts, preferably with longitudinal follow-up and mortality data, is necessary to confirm these observations and elucidate the functional implications of SIRT6 genetic variation in aging and frailty.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available and cannot be shared at this time due to intellectual property restrictions and their ongoing use in further research. However, they may be made available from the corresponding author, [Farshad Sharifi], upon reasonable request and after the completion of the ongoing related studies.

Abbreviations

- BLAS:

-

Birjand Longitudinal Aging Study

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MAF:

-

Minor Allele Frequency

- MNA:

-

Mini Nutritional Assessment

- PCR-RFLP:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SIRT6:

-

Sirtuin-6

References

Dent, E. et al. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet 394, 1376–1386 (2019).

Veronese, N. et al. Prevalence of multidimensional frailty and pre-frailty in older people in different settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 72, 101498 (2021).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M157 (2001).

Yang, X. et al. Roles of SIRT6 in kidney disease: a novel therapeutic target. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1–9 (2021).

Chang, A. R. & Mostoslavsky, R. SIRT6, a mammalian deacylase with multitasking abilities. Physiol. Rev. 100, 145–169 (2020).

Liu, G. et al. Emerging roles of SIRT6 in human diseases and its modulators. Med. Res. Rev. 41, 1089–1137 (2021).

Xiao, C. et al. Progression of chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis driven by activation of c-JUN signaling in Sirt6 mutant mice. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41903–41913 (2012).

Vitiello, M. et al. Multiple pathways of SIRT6 at the crossroads in the control of longevity, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 35, 301–311 (2017).

Santos-Barriopedro, I. et al. SIRT6-dependent cysteine monoubiquitination in the PRE-SET domain of Suv39h1 regulates the NF-κB pathway. Nat. Commun. 9, 101 (2018).

Roichman, A. et al. Restoration of energy homeostasis by SIRT6 extends healthy lifespan. Nat. Commun. 12, 3208 (2021).

Zhu, M. et al. Serum SIRT6 levels are associated with frailty in older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 27, 719–725 (2023).

Hirvonen, K. et al. SIRT6 polymorphism rs117385980 is associated with longevity and healthy aging in Finnish men. BMC Med. Genet. 18, 1–5 (2017).

TenNapel, M. J. et al. SIRT6 minor allele genotype is associated with > 5-year decrease in lifespan in an aged cohort. PLoS One. 9, e115616 (2014).

You, L. I. et al. Association of SIRT6 gene polymorphisms with human longevity. Iran. J. Public. Health. 45, 1420 (2016).

Lin, R. et al. Lack of association between polymorphisms in the SIRT6 gene and longevity in a Chinese population. Mol. Cell. Probes. 30, 79–82 (2016).

Naiman, S. et al. SIRT6 promotes hepatic beta-oxidation via activation of PPARα. Cell. Rep. 29, 4127–4143 (2019).

Moodi, M. et al. Birjand longitudinal aging study (BLAS): the objectives, study protocol and design (wave I: baseline data gathering). J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 19, 551–559 (2020).

Delbari, A. et al. Prevalence of frailty and associated socio-demographic factors among community-dwelling older people in Southwestern iran: a cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 20, 601–610 (2021).

Sobhani, A. et al. Low physical activity is the strongest factor associated with frailty phenotype and frailty index: data from baseline phase of Birjand longitudinal aging study (BLAS). BMC Geriatr. 22, 498 (2022).

Allison, R. 2, Assadzandi, S., Adelman, M. & nd, & Frailty: evaluation and management. Am. Fam Physician. 103, 219–226 (2021).

Korotkov, A., Seluanov, A. & Gorbunova, V. Sirtuin 6: linking longevity with genome and epigenome stability. Trends Cell. Biol. 31, 994–1006 (2021).

Ferrer, C. M. et al. An inactivating mutation in the histone deacetylase SIRT6 causes human perinatal lethality. Genes Dev. 32, 373–388 (2018).

Xu, Z. et al. SIRT6 rescues the age related decline in base excision repair in a PARP1-dependent manner. Cell. Cycle. 14, 269–276 (2015).

Geng, A. et al. The deacetylase SIRT6 promotes the repair of UV-induced DNA damage by targeting DDB2. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 9181–9194 (2020).

Tian, X. et al. SIRT6 is responsible for more efficient DNA double-strand break repair in long-lived species. Cell 177, 622–638 (2019).

Meng, F. et al. Synergy between SIRT1 and SIRT6 helps recognize DNA breaks and potentiates the DNA damage response and repair in humans and mice. Elife 9, e55828 (2020).

Liszczak, G. et al. Acetylation blocks DNA damage–induced chromatin ADP-ribosylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 837–840 (2018).

Mao, Z. et al. SIRT6 promotes DNA repair under stress by activating PARP1. Science 332, 1443–1446 (2011).

Mao, Z. et al. Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) rescues the decline of homologous recombination repair during replicative senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 11800–11805 (2012).

Tan, J. et al. An ordered assembly of MYH glycosylase, SIRT6 protein deacetylase, and Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 checkpoint clamp at oxidatively damaged telomeres. Aging (Albany NY). 12, 17761 (2020).

Simon, M. et al. LINE1 derepression in aged wild-type and SIRT6-deficient mice drives inflammation. Cell. Metab. 29, 871–885 (2019).

Van Meter, M. et al. SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nat. Commun. 5, 5011 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. SIRT6 enhances telomerase activity to protect against DNA damage and senescence in hypertrophic ligamentum flavum cells from lumbar spinal stenosis patients. Aging (Albany NY). 13, 6025 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences and Metabolism, Tehran, Iran. Special thanks are extended to the Elderly Health Research Center for providing the invaluable Birjand Longitudinal Aging Study (BLAS) samples. We acknowledge the use of Gemini AI and DeepSeek AI tools, which assisted in enhancing the writing quality of this paper alongside the authors’ efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: MA, ES, FS, VH. Laboratory work and data collection: ES, ZN, AV, RL. Performed statistical analysis: FS. Wrote the manuscript: ES. Critically reviewed and edited the manuscript: MA, FS, ES, VH.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study utilized samples from the Birjand Longitudinal Aging Study (BLAS), a prospective cohort study approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Phase I: Ir.bums.REC.1397.54; Phase II: IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1399.071). Prior to the original data collection, all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikholmolouki, E., Sharifi, F., Nickhah, Z. et al. The association of the SIRT6 rs117385980 variant with frailty and longevity: an exploratory study. Sci Rep 15, 40251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24018-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24018-3