Abstract

Multiple-choice questions constitute a critical format for assessing language application proficiency in standardized English tests, such as BEC and TOEIC. Developing explanatory content for such materials traditionally relies heavily on manual labor in test item analysis, which is labor-intensive and time-consuming. Consequently, Artificial Intelligence (AI) approaches centered on Machine Reading Comprehension for Multiple Choice (MCRC) are becoming the preferred solution for generating auxiliary educational content. This task demands models capable of profoundly understanding textual semantics and accurately identifying complex relationship patterns between passages, questions, and answer options. Although Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) have achieved remarkable success on MCRC tasks, existing methods confront two primary limitations: (1) they remain susceptible to misclassifying highly textually similar yet semantically distant distractor options (e.g. synonymous business terms); (2) they exhibit significantly diminished accuracy when tackling questions requiring indirect reasoning or background knowledge to identify implicit answers. To address these challenges, this paper proposes Contrastive Learning-driven Hierarchical Attention Model for Multiple Choice (CL-HAMC). The proposed model innovatively employs multi-head attention mechanisms to hierarchically model the triple interactions among passages, questions, and options, simulating the progressive, multi-layered reasoning process humans undertake during problem-solving. Furthermore, it incorporates a contrastive learning strategy to sharpen the model’s ability to discern nuanced semantic distinctions among answer choices. Extensive experiments on the RACE, RACE-M, and RACE-H benchmarks demonstrate that CL-HAMC achieves substantial and consistent performance gains, establishing a new state-of-the-art (SOTA) on all three datasets. Moreover, CL-HAMC exhibits competitive results on the DREAM dataset. This study provides an effective solution towards the automated processing of highly distractor-rich multiple-choice questions within the English auxiliary learning domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

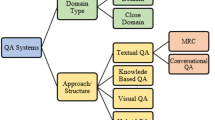

Machine Reading Comprehension (MRC), as a core task in natural language processing, aims to enable machines to accurately answer questions based on a given text. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of deep learning techniques, MRC has achieved significant progress in both dataset construction and model development. Depending on the answer format, MRC tasks can be categorized into four types: cloze-style (e.g. CNN & Daily Mail dataset1), multiple-choice (e.g. RACE dataset2), span-extraction (e.g. SQuAD dataset3), and open-ended generation (e.g. MS MARCO dataset4). Among these, Multiple-Choice Reading Comprehension (MCRC) requires models to identify the correct answer from a set of given options. Often, the correct answer cannot be directly extracted from the passage but requires reasoning over the deep semantic relationships between the passage, question, and options, thus imposing higher demands on models’ semantic understanding and reasoning capabilities.

MCRC techniques have demonstrated significant applicability across multiple interdisciplinary domains. For instance, in intelligent processing of business English, these techniques have been successfully applied to scenarios such as communication and signal processing, as well as biomedical literature analysis, providing critical technological support for improving efficiency in international trade and cross-lingual collaboration. The advantages are twofold: first, they help resolve terminological ambiguities in formal texts such as legal contracts (e.g. differences in interpretation of FOB and CIF clauses across legal systems5); second, they enable inference of implicit intentions in cross-cultural business communication (e.g. indirect expressions commonly used in East Asian business emails6), thereby supporting decision-making and communication.

To systematically evaluate models’ performance on these capabilities, researchers widely adopt the RACE and DREAM multiple-choice reading comprehension datasets as benchmarks. RACE (Lai et al.2), derived from English exams for Chinese middle and high school students, is currently the largest English MCRC dataset, covering texts from multiple disciplines. DREAM7, on the other hand, centers on multi-turn dialogues and simulates authentic business interactions. Figure 1 illustrates a representative example from the RACE dataset along with its structural characteristics.The two datasets exhibit complementary characteristics in terms of task features: the RACE dataset is characterized by higher reasoning complexity and a dense use of domain-specific terminology, aligning more closely with the demands of standardized tests that assess deep text comprehension and logical reasoning abilities; in contrast, the DREAM dataset, leveraging its dialogue-based structure, faithfully replicates authentic communicative scenarios in business English (such as client negotiations and email correspondence), emphasizing the cultivation of practical language application and interactive skills.

In recent years, pre-trained language models represented by BERT8, RoBERTa9, and ALBERT10 have achieved remarkable results on multiple-choice reading comprehension (MCRC) tasks. By pre-training on large-scale corpora, these models can effectively capture deep linguistic features, thereby demonstrating superior performance in MCRC tasks. The Option Comparison Network (OCN) proposed by Ran et al. identifies correlations between answer options through word-level comparisons, thereby facilitating reasoning in MCRC. DCMN+11 employs a bidirectional matching mechanism that considers not only the relevance between the question and the passage but also the relevance between the options and the passage, providing a more comprehensive modeling of the semantic relationships among the passage, the question, and the candidate options. The MMM framework12 adopts a multi-stage task learning strategy: in the first stage, external data are used for coarse-tuning to enhance the model’s reasoning ability; in the second stage, fine-tuning is performed on MCRC datasets to further improve task-specific performance.

All of the above matching-based models rely on pre-trained models for semantic encoding of the context, considering both the correct answer and distractors simultaneously. This approach, however, limits the model’s ability to accurately capture differences between options:

-

1.

When options exhibit high surface-level textual similarity but significant semantic differences (e.g. near-homographs like “affect” vs. “effect”), the model often struggles to discern the semantic distinctions and tends to rely on shallow linguistic patterns, leading to incorrect selection.

-

2.

Although current pre-trained models can effectively capture textual features, they face difficulties in providing correct answers when certain candidate options lack explicit support in the passage or question.

This study aims to more accurately capture the differences between answer options and to simulate the human cognitive process in solving multiple-choice MCRC tasks. We propose a Contrastive Learning-driven Hierarchical Attention Multiple-Choice model (CL-HAMC). When humans tackle MCRC tasks, the process typically involves multi-level cognitive operations: first, semantic encoding and integration of the text are performed to establish a textbase and a situation model; subsequently, fine-grained relational reasoning occurs between the question and the options, wherein subtle differences among options are compared, distractor representations are suppressed, and the semantic association of the correct option is reinforced.

Inspired by this cognitive mechanism, the proposed model leverages the multi-head attention13 module in pre-trained language models to explicitly model interactions among the passage, question, and options at multiple levels—including word-level, phrase-level, and semantic-relation-level. Additionally, a contrastive learning mechanism is introduced: by constructing positive and negative sample pairs, the representation of the question is pulled closer to the correct option and pushed farther from incorrect options, thereby better capturing discriminative features among options.

This approach not only structurally aligns with the hierarchical cognitive strategy humans use for option comparison and reasoning, but also explicitly models option differences in the representation space via contrastive learning, enhancing the model’s discriminative capability in MCRC tasks. The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

We propose a CL-HAMC, which effectively enhances the model’s information extraction capability by improving the identification of both correlations and distinctions among answer options.

-

2.

The model simulates the human cognitive process in solving multiple-choice reading comprehension (MCRC) tasks, employing a hierarchical attention mechanism to progressively focus on the interactions among passages, questions, and options, thereby significantly mitigating errors caused by highly similar distractors.

-

3.

Extensive experiments were conducted on multiple benchmark datasets, including RACE, RACE-M, RACE-H, and DREAM. The results demonstrate substantial performance improvements, validating the model’s effectiveness and generalization capability.

Reated work

Multiple-choice machine reading comprehension

With the release of large-scale multiple-choice reading comprehension (MCRC) datasets and the rapid advancement of pre-trained models, MCRC has evolved from traditional approaches to deep learning paradigms, achieving substantial performance gains. Early works, such as the introduction of attention mechanisms by Bahdanau et al.14, provided new perspectives for natural language processing and were subsequently applied to MCRC. Huang et al.15 proposed a co-matching framework that employed dual attention and hierarchical LSTMs to integrate information across multiple sentences, significantly enhancing cross-sentence reasoning, yet it lacked explicit modeling of inter-option contrasts. Subsequent studies have further refined representation alignment and discriminative power: Kim et al.16 progressively eliminate demonstrably incorrect choices, whereas Zhang et al.11 jointly optimize key-sentence selection and fine-grained option comparison.

Later research focused on enhancing semantic understanding and reasoning precision through multi-stage, multi-task, and multi-head collaborative mechanisms. Jin et al.12’s multi-stage, multi-task framework mitigated the scarcity of annotated data in low-resource settings; and Zhu et al.17’s dual multi-head collaborative attention model performed global-local interactions across passages, questions, and options, yielding further gains in reasoning accuracy. However, these approaches generally suffer from complex architectures, high computational cost, and optimization challenges.

Recent efforts highlight the critical role of data and training strategies in performance improvement. Longpre et al.18 demonstrated the impact of data quality on MCRC outcomes; Li et al.19 proposed next-generation dataset construction methods; Bai et al.20 introduced a multi-role collaborative data selection framework that effectively reduces misclassification of distractors. Collectively, existing research can be categorized into four areas: attention and matching mechanisms, option interaction modeling, data and training strategies, and pre-training paradigm enhancements. Nonetheless, common limitations remain, including insufficient fine-grained modeling of option differences, heavy reliance on high-quality data, and challenges in model complexity and optimization.

Contrastive learning

Contrastive Learning (CL), initially applied in computer vision, is an unsupervised approach that learns feature representations by pulling similar samples closer while pushing dissimilar samples apart. SimCLR21, a seminal contrastive learning framework, constructs positive-negative sample pairs via data augmentation and leverages the InfoNCE loss function to learn rich feature representations from these pairs. SimCSE22 first introduced contrastive learning to natural language processing, learning textual sentence embeddings based on SimCLR. Its core methodology maximizes similarity between semantically related sentence pairs while minimizing similarity between unrelated pairs, thereby acquiring sentence embeddings with semantic coherence. ArcCon23 developed an angular space contrastive learning approach, which captures angular relationships between sentences through angle-constrained cosine similarity and further refines sentence representations using<anchor, positive, negative> triplets. PairSCL24 proposed a supervised sentence-level contrastive learning method that employs cross-attention mechanisms to derive joint representations of sentence pairs, narrowing distances between same-class pairs and expanding distances between different-class pairs through contrastive objectives. Shorinwa et al.25 systematically reviewed uncertainty quantification methods for large language models (LLMs) and highlighted that semantic similarity–driven contrastive learning (e.g. Semantic-Similarity UQ) can effectively mitigate misclassification of highly similar distractors.Our work integrates contrastive learning without extra information augmentation, precisely capturing distinctions among options to significantly enhance the model’s discriminative capacity.

Methodology

Problem definition

Given a triplet \(\langle P, Q, O \rangle\), where \(P = \{P_1, P_2, \ldots , P_m\}\) represents a passage composed of m sentences, Q denotes a question related to the passage, and \(O = \{O_1, O_2, \ldots , O_n\}\) is an option set containing n candidate answers. The model’s objective is to learn a probability distribution function: \(F(O_1, O_2, \ldots , O_n \mid P, Q)\).

CL-HAMC model

The model framework proposed in this work is illustrated in Fig. 2, and consists of three core components: a context encoder, a contrastive learning–driven hierarchical attention module, and a decoder. The context encoder first transforms the input natural language text—including passages, questions, and candidate options—into machine-interpretable semantic feature representations, providing the foundation for subsequent deep analysis and reasoning. Building upon these encoded features, the contrastive learning–driven hierarchical attention module simulates the cognitive process of humans performing MCRC. In the first stage, a hierarchical attention mechanism captures interactions among passages, questions, and options across multiple granularities, from word-level to sentence-level and semantic-level. Subsequently, a contrastive learning strategy is introduced to enlarge the representational distance between correct and incorrect options, thereby enhancing the model’s sensitivity to fine-grained differences among options. Finally, the decoder integrates the multi-level, multi-granularity information extracted in the preceding stages and conducts comprehensive comparison and reasoning over all candidate options to produce the final answer.

Encoder

Pretrained models incorporate extensive out-of-domain knowledge that efficiently captures contextual semantic information during text encoding. We therefore employ a pretrained model as the encoder to encode passages, questions, and options into fixed-dimensional feature vectors:

where \(\text {Encoder}(\cdot )\) outputs the feature representation from the final linear layer of the pretrained model. Here \(\textbf{h}^p \in \mathbb {R}^{|P| \times l}\), \(\textbf{h}^q \in \mathbb {R}^{|Q| \times l}\), and \(\textbf{h}^o \in \mathbb {R}^{|O| \times l}\) denote the embedding vectors of the passage, question, and options respectively. The terms |P|, |Q|, and |O| represent input sequence lengths, while l denotes the hidden dimension of the pretrained model.

Contrastive learning-driven hierarchical attention module

Hierarchical attention module

Simulating human cognition in MCRC tasks—locating relevant contextual information before selecting answers from options—our modular architecture employs stackable hierarchical attention modules to extract deep features of \(\langle P, Q, O \rangle\) (default \(k=1\) layer). Passage-question fusion \(\textbf{h}^{pq}\) is derived via Eq. (4), while question-option fusion \(\textbf{h}^{qo}\) via Eq. (5):

Cross-level semantic interactions are captured through attention mechanisms: Eq. (6) computes relevance with \(\textbf{h}^{pq}\) as Query and \(\textbf{h}^o\) as Key/Value, while Eq. (7) symmetrically processes \(\textbf{h}^{qo}\) and \(\textbf{h}^p\):

Multi-head attention enriches representations by parallel computation and concatenation:

where MLP(\(\cdot\)) outputs \(\mathbb {R}^{d_{\text {model}} \times l}\) features. Learnable parameters include: \(\textbf{W}_i^Q \in \mathbb {R}^{d_{\text {model}} \times d_q}\), \(\textbf{W}_i^K \in \mathbb {R}^{d_{\text {model}} \times d_k}\), \(\textbf{W}_i^V \in \mathbb {R}^{d_{\text {model}} \times d_v}\) per head, and fusion matrix \(\textbf{W}^F \in \mathbb {R}^{h \cdot d_v \times d_{\text {model}}}\). This hierarchical multi-head design significantly enhances MCRC performance.

Contrastive learning module

Contrastive learning enhances feature discrimination by comparing inter-sample similarities and differences. To capture nuanced distinctions among options, we integrate contrastive learning as follows: First, apply mean pooling to MHA outputs to obtain feature vectors g (Eqs. 11 and 12). For each sample i in batch \(\mathcal {B}\), we construct positive pairs \((g_1^i, g_2^i)\) and treat other samples as negatives. The contrastive loss \(\mathcal {L}_{cl}\) is computed via InfoNCE:

where \(\text {sim}(\cdot )\) computes cosine similarity, \(\tau\) is a temperature hyperparameter, and \(k \ne i\) enforces negative sampling.

The fused representation \(C_i\) combines dual-path features for final prediction (Eq. 14), with three fusion strategies ablated in Sect. 4.3 (Fig. 3):

where \(C_i \in \mathbb {R}^l\), and \(\text {Fuse}(\cdot )\) denotes element-wise product, concatenation, or MLP-based fusion.

Decoder

We compute probability distributions over candidate options, where \(O_i\) denotes the ith option, \(C_i\) represents the output features of the \(\langle P, Q, O_i \rangle\) triplet, and \(O_k\) indicates the correct answer. The predictive loss is defined in Eq. (15), while the final objective function combines it with contrastive loss via weighted summation (Eq. 16) to drive model training:

where \(\textbf{W} \in \mathbb {R}^l\) is a learnable parameter, n is the number of candidate options, and \(\lambda\) is a weighting hyperparameter.

Experimental results

The RACE (Reading Comprehension from Examinations) dataset2, a canonical benchmark for MCRC tasks, comprises English examination questions from Chinese secondary schools. It is stratified by difficulty into two subsets: RACE-M for middle school and RACE-H for high school. As detailed in Table 1, the complete dataset contains 27,933 passages and 97,687 questions, with RACE-M consisting of 7139 passages and 28,293 questions, while RACE-H includes 20,794 passages and 69,394 questions. Data splits allocate 90% to training, 5% to validation, and 5% to test sets.

DREAM (Dialogue-based REAding comprehension exaMination) is a dialogue-oriented multiple-choice reading comprehension dataset proposed by Sun et al.7. The dataset is collected from real English language examinations and contains 6444 dialogues and 10,197 associated questions. Unlike RACE, DREAM has several distinguishing characteristics:

-

1.

Dialogue structural complexity: each dialogue contains an average of 5.2 turns, with answers often distributed across multiple turns;

-

2.

Diverse reasoning patterns: 84% of the answers require context-dependent inference, and 34% of the questions rely on external commonsense knowledge (e.g. answering “Sam might attend the party” requires understanding the implicit commitment conveyed by “promised to come”);

-

3.

Dynamic options: the number of options per question is not fixed (averaging 3.3 options per question) and includes many colloquial near-synonyms (e.g. distinguishing between “likely” and “probably”).

Regarding data usage, this study strictly follows the data split methodology proposed by Zhu et al.17 (specific proportions and composition are detailed in Table 1) to ensure the comparability and reproducibility of experimental settings.

Evaluation metrics

In multiple-choice machine reading comprehension (MCRC) tasks, accuracy serves as the primary evaluation metric:

where \(N^+\) denotes correct predictions and N the question count.

Experimental environment

ALBERT-xxlarge encoder with \(k=2\) hierarchical attention modules; PyTorch implementation; 10 training epochs; Learning rate \(2\times 10^{-5}\); 0.1 dropout per layer; \(\tau =0.05\), \(\lambda =0.2\); LAMB optimizer26 (batch size 8, 2000-step warmup); 4 nvidia RTX 4090 Ti GPUs.

Results and analysis

This section conducts a comprehensive comparative analysis between our proposed model and state-of-the-art multiple-choice reading comprehension (MCRC) approaches. To ensure experimental reliability, we perform 10 independent training runs with different random seeds, reporting the averaged results as final performance metrics. This methodology minimizes random fluctuations and enables precise assessment of model capability.

For the UDG-LLM27 model, we use the BERTScore settings from the original paper to perform semantic matching between the model outputs and the reference answers. Specifically, for each candidate option, we compute its BERTScore with the reference answer, and the option with the highest similarity is taken as the model’s prediction. If this option matches the correct reference answer, the prediction is considered correct, and the model’s overall accuracy is subsequently calculated.

As evidenced in Table 2, the proposed model demonstrates superior performance across all RACE difficulty levels. Compared to the state-of-the-art (SOTA) ALBERT-xxlarge+DUMA, it achieves accuracy improvements of +1.1%, +0.4%, and +0.7% on RACE-M, RACE-H, and the full RACE dataset respectively, establishing its effectiveness for MCRC tasks. Crucially, versus the base ALBERT-xxlarge encoder, the model attains more substantial gains of +3.3%, +3.5%, and +2.7% on these benchmarks. These results indicate that by hierarchically extracting semantic features and discerning nuanced option disparities, the model not only enhances semantic representation but also significantly boosts generalization capability, validating its efficacy for complex reading comprehension scenarios.

As shown in Table 3, on the DREAM dataset, the proposed method achieves a 2.3% improvement in accuracy over the baseline ALBERT-xxlarge model, demonstrating a significant advantage over existing approaches. Compared with the state-of-the-art UDG-LLM model, our method exhibits a slight performance gap (1.27% lower), which may be attributed to UDG-LLM’s use of larger or more complex model parameters. Future work could explore integrating CL-HAMC with UDG-LLM to further exploit the potential of the MCRC task. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of our approach in handling complex dialogue structures and semantic reasoning, confirming its capability to achieve advanced semantic understanding and inference within conversational contexts.

Ablation experiment

To assess the contributions of individual components, we conducted ablation studies on the RACE dataset, focusing on the hierarchical attention module, the contrastive learning module, and the integration strategy. Systematic experiments verified the effectiveness of each module and associated parameters in enhancing semantic feature extraction and discriminating correlations among candidate options.

Context encoder module

To evaluate the impact of different pre-trained language models as the context encoder, we conducted comparative experiments using BERT-large, RoBERTa-large, XLNet-large, and ALBERT-xxlarge while keeping all other modules unchanged. This setup systematically investigates the influence of encoder architecture on overall model performance. Detailed experimental results are presented in Table 4.

It can be clearly observed from Table 4 that the ALBERT-xxlarge+CL-HAMC model achieves the best performance, attaining 92.3% accuracy on RACE-M, 89.0% on RACE-H, and 90.1% on the overall RACE dataset. This result significantly outperforms other CL-HAMC–based models, surpassing XLNet-large+CL-HAMC by 2.7% on RACE-M, 0.7% on RACE-H, and 0.6% on the full RACE dataset. These findings indicate that the combination of ALBERT-xxlarge with the CL-HAMC module not only fully leverages the strong semantic representation capability of ALBERT-xxlarge but also further enhances the model’s ability to comprehend complex textual structures and multiple-choice questions through the CL-HAMC module.

Hierarchical attention module

For the hierarchical attention module, this section focuses on the experimental validation of the hierarchical attention of article-question pairs and candidate items, question-candidate pairs and articles, while ensuring that the other modules remain unchanged, and Table 5 shows the effect on the model of this paper under the removal of different hierarchical attention.

The full model incorporates all hierarchical attention components. Table 5 demonstrates that ablating individual interaction modules degrades overall performance by 1.6% and 1.3% respectively, while removing all hierarchical attention causes a significant 2.8% decline. This confirms that our hierarchical attention mechanism enhances cross-level feature representations among passages, questions, and options, effectively capturing critical semantic relationships.

As shown in Fig. 4, we vary the stacking depth of attention layers (k = 1 to 6) on RACE validation/test sets. Optimal performance occurs at k=2 layers, beyond which performance plummets drastically (k > 5). This degradation may stem from vanishing gradients or overfitting during model training.

Contrastive learning module

To further investigate the impact of the contrastive learning module on model performance, we conducted systematic ablation experiments on the loss weighting coefficient (\(\lambda\)). By keeping all other components fixed, the hyperparameter was varied over \(\lambda \in \{0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8\}\). The results are illustrated in the figure, where the training curves represent the overall loss trends and the validation curves indicate the convergence of the Variation of Information (VOI) metric. The shaded areas reflect the variance observed across different experimental settings.

Convergence of training and validation curves under different \(\lambda\) values. Solid lines indicate training loss and validation results (VOI); shaded regions represent variance. \(\sigma \_{\textrm{train}}\) and \(\sigma \_{\textrm{valid}}\) denote the mean variances of the training and validation curves, respectively.

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of the weighting parameter \(\lambda\) on model convergence and stability. When \(\lambda = 0\), both training and validation curves exhibit pronounced fluctuations, with the largest variance. Settings of \(\lambda = 0.4\) and 0.8 improve stability compared to \(\lambda = 0\), but remain inferior to \(\lambda = 0.2\). Notably, \(\lambda = 0.2\) achieves the best performance, with faster convergence, minimal variance after approximately 50k iterations, and the most stable trend. This indicates that a moderate contrastive learning weight enhances feature discrimination and generalization, whereas excessive \(\lambda\) causes the contrastive loss to dominate, weakening the main task and inducing instability. Therefore, \(\lambda = 0.2\) provides the optimal balance between the main task and contrastive learning.

While keeping all other module parameters unchanged, we further extracted the association features between context–question pairs and candidate options, and visualized them as a correlation matrix heatmap (Fig. 6). In the figure, color intensity is proportional to the strength of the feature correlations, providing an intuitive illustration of the semantic association differences among options with respect to the context–question pairs.

Figure 6 illustrates the feature correlations between candidate options and the passage–question pairs. For Question 1, heatmap (a) shows pronounced differences among options, with option D exhibiting the highest correlation, which corresponds to the predicted answer. In contrast, heatmap (b) indicates option C as having the highest correlation, while the distinctions among options are less marked. These results suggest that incorporating contrastive learning enhances the model’s ability to discriminate fine-grained differences among candidate options.

For Question 2, the required answer cannot be directly inferred from the passage. Nevertheless, by leveraging inter-option differences and integrating passage and question information, the model successfully identifies the relevant candidate. Specifically, it recognizes that sentence 14 (“horseless carriage”) was invented by Henry Ford, and sentence 16 describes the establishment of the “Ford Motor Company,” resulting in option B having the highest correlation and being correctly predicted. These findings demonstrate the model’s capacity for reasoning beyond explicit textual evidence by capturing subtle semantic distinctions among options.

Fusion strategy

Fusion strategies play a critical role in the final output features of the model. This paper conducts experiments on three fusion methods: multiplication, concatenation, and linear layer fusion. Specifically, multiplication employs element-wise multiplication for feature fusion; concatenation directly joins two features to form the output feature vector; linear layer fusion utilizes a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to extract abstract semantic information from feature vectors, with its hidden layer dimension set to 512. Figure 7 demonstrates the performance of different fusion strategies on RACE-M, RACE-H, and RACE datasets.

As shown in Fig. 7, the model employing the MLP integration strategy outperforms the other two strategies in terms of accuracy, while also exhibiting lower variance and higher stability. Although the introduction of the MLP integration incurs some computational overhead, it achieves the optimal trade-off between performance, stability, and accuracy. The modest increase in computational cost is justified by the significant improvement in performance and enhanced stability, making the MLP integration strategy the chosen solution for the final model.

Conclusion

We identify two core challenges in intelligent multiple-choice comprehension in English education: discriminating highly confounding options and inferring implicit answers. To address these challenges, we propose CL-HAMC (Contrastive Learning–driven Hierarchical Attention Model), which simulates human-like progressive reasoning in business contexts through hierarchical interactions among text, questions, and options, while leveraging contrastive learning to enhance sensitivity to subtle semantic differences between near-synonymous terms.

Experiments on the RACE benchmark dataset demonstrate that CL-HAMC outperforms state-of-the-art methods, achieving up to 0.7% improvement in accuracy, and also exhibits strong performance on the DREAM dataset, confirming the synergistic effectiveness of hierarchical attention and contrastive learning. Our work provides a scalable solution for automated English education, with particular applicability to standardized test item generation and AI-driven question-answering systems. Future research will focus on developing cross-domain adaptation frameworks for business knowledge (e.g. finance and law) and constructing interactive tutoring systems with real-time adaptive feedback capabilities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hermann, K. M. et al. Teaching machines to read and comprehend. In Proc. of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 1, NIPS’15, 1693–1701 (MIT Press, 2015).

Lai, G., Xie, Q., Liu, H., Yang, Y. & Hovy, E. RACE: Large-scale ReAding comprehension dataset from examinations. In Proc. of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds. Palmer, M. et al.) 785–794 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2017), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D17-1082.

Rajpurkar, P., Jia, R. & Liang, P. Know what you don’t know: Unanswerable questions for SQuAD. In Proc. of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (eds. Gurevych, I. & Miyao, Y.) 784–789 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P18-2124.

Nguyen, T. et al. Ms marco: A human generated machine reading comprehension dataset. Choice 2640, 660 (2016).

Bridge, M. Cif and fob contracts in English law: Current issues and problems. In Research Handbook on International and Comparative Sale of Goods Law (ed. Bridge, M.) 213–239 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019).

Jung, Y. Korean Business Communication: A Comprehensive Introduction (Taylor & Francis, 2022).

Sun, K. et al. DREAM: A challenge data set and models for dialogue-based reading comprehension. Tran. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 7, 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00264 (2019).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proce. of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (eds. Burstein, J. et al.) 4171–4186, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1423 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019).

Zhuang, L., Wayne, L., Ya, S. & Jun, Z. A robustly optimized BERT pre-training approach with post-training. In Proc. of the 20th Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics (eds. Li, S. et al.) 1218–1227 (Chinese Information Processing Society of China, 2021).

Lan, Z. et al. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. In 8th International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Dcmn+: Dual co-matching network for multi-choice reading comprehension. Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 9563–9570. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6502 (2020).

Jin, D., Gao, S., Kao, J.-Y., Chung, T. & Hakkani-tur, D. Mmm: Multi-stage multi-task learning for multi-choice reading comprehension. Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial IntelligenceProc. AAAI Conference on Artificial IntelligenceProc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 8010–8017. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6310 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17, 6000–6010 (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. H. & Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. In 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015 (2015).

Wang, S., Yu, M., Jiang, J. & Chang, S. A co-matching model for multi-choice reading comprehension. In Proc. of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers)(eds. Gurevych, I. & Miyao, Y.) 746–751 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P18-2118.

Kim, H. & Fung, P. Learning to classify the wrong answers for multiple choice question answering (student abstract). Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 13843–13844. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i10.7194 (2020).

Zhu, P., Zhang, Z., Zhao, H. & Li, X. Duma: Reading comprehension with transposition thinking. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Proc. 30, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2021.3138683 (2022).

Longpre, S. et al. A pretrainer’s guide to training data: Measuring the effects of data age, domain coverage, quality, & toxicity. In Proc. of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Duh, K., Gomez, H. & Bethard, S.) 3245–3276 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.naacl-long.179.

Li, J. et al. Datacomp-lm: In search of the next generation of training sets for language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 14200–14282 (2024).

Bai, T. et al. Efficient pretraining data selection for language models via multi-actor collaboration. In Proc. of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Che, W. et al. 9465–9491 (Association for Computational, 2025), DOI: https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.466.

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proc. of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’20 (JMLR.org, 2020).

Gao, T., Yao, X. & Chen, D. SimCSE: Simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. In Proc. of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds. Moens, M.-F. et al.) 6894–6910 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.552.

Zhang, Y. et al. A contrastive framework for learning sentence representations from pairwise and triple-wise perspective in angular space. In Proc. of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Muresan, S. et al.) 4892–4903, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.336 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 2022).

Li, S., Hu, X., Lin, L. & Wen, L. Pair-level supervised contrastive learning for natural language inference. In ICASSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 8237–8241, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9746499 (2022).

Shorinwa, O., Mei, Z., Lidard, J., Ren, A. Z. & Majumdar, A. A survey on uncertainty quantification of large language models: Taxonomy, open research challenges, and future directions. ACM Comput. Surv. https://doi.org/10.1145/3744238 (2025).

You, Y. et al. Large batch optimization for deep learning: Training bert in 76 minutes. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Qu, F., Sun, H. & Wu, Y. Unsupervised distractor generation via large language model distilling and counterfactual contrastive decoding. In Ku, L.-W., Martins, A. & Srikumar, V. (eds.) Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 827–838, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.findings-acl.47 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 2024).

Richardson, M., Burges, C. J. & Renshaw, E. MCTest: A challenge dataset for the open-domain machine comprehension of text. In Proc. of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds. Yarowsky, D. et al.) 193–203 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2013).

Dhingra, B., Liu, H., Yang, Z., Cohen, W. & Salakhutdinov, R. Gated-attention readers for text comprehension. In Proc. of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Barzilay, R. & Kan, M.-Y.) 1832–1846 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2017), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P17-1168.

Chen, D., Bolton, J. & Manning, C. D. A thorough examination of the CNN/Daily Mail reading comprehension task. In Proc. of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Erk, K. & Smith, N. A.) 2358–2367 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2016), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P16-1223.

Parikh, S., Sai, A., Nema, P. & Khapra, M. Eliminet: A model for eliminating options for reading comprehension with multiple choice questions. In Proc. of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-18, 4272–4278 (International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 2018), https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2018/594.

Zhu, H., Wei, F., Qin, B. & Liu, T. Hierarchical attention flow for multiple-choice reading comprehension. In Proc. of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI’18/IAAI’18/EAAI’18 (AAAI Press, 2018).

Radford, A. Improving language understanding with unsupervised learning. OpenAI Res. (2018).

Sun, K., Yu, D., Yu, D. & Cardie, C. Improving machine reading comprehension with general reading strategies. In Proc. of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (eds. Burstein, J. et al.) 2633–2643 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019), https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1270.

Yang, Z. et al. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding (Curran Associates Inc., 2019).

He, P., Gao, J. & Chen, W. DeBERTav3: Improving deBERTa using ELECTRA-style pre-training with gradient-disentangled embedding sharing. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Funding

This work is supported by Research Project of Henan Province’s Cultural Promotion Project in 2024 [2024XWH225].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lina Ji:Supervision,Writing–original draft.Linghua Yao:Writing–review and editing.Wei Xu:Software,Data curation,Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, L., Yao, L. & Xu, W. English-focused CL-HAMC with contrastive learning and hierarchical attention for multiple-choice reading comprehension. Sci Rep 15, 40246 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24031-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24031-6