Abstract

In this paper, we successfully developed a rapid and straightforward one-pot synthesis method for klockmannite CuSe nanoparticles, demonstrating their potential application in supercapacitors. This synthesis is notably faster and simpler than previously reported methods, requiring no specialized equipment, and can be completed in just 30 min. This process consistently produces 2 nm CuSe nanoparticles with a well-defined hexagonal crystal structure, which is ideal for enhancing supercapacitor electrode performance. In our study, CuSe@SP (Copper selenide supported on SuperP carbon) electrodes exhibited optimal results in TBABF₄ electrolyte, achieving low resistance, high conductivity, and elevated energy density. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that electrolyte properties—especially ion concentration and the size of negative anions—play a critical role in determining ion transfer rates, with smaller anions significantly enhancing performance. These results not only highlight the potential of our rapid synthesis method but also contribute to a deeper fundamental understanding of electrolyte behavior in advanced supercapacitor systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, global population growth has led to increased consumption of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, resulting in their significant deficiency.1,2,3,4,5 The consumption of fossil fuels primarily causes pollutants release, leading to irreversible damage to the environment and Earth’s climate.2,3,4 Global warming, coupled with the depletion of fossil fuels, has prompted the search for alternative renewable energy sources and the necessary technologies to store this energy.3,6 Energy storage technologies that provide solutions for storing and releasing sustainable energy consist of three main types: batteries, capacitors, and fuel cells.2,7,8,9,10.

In the last decades, a new technology known as “Supercapacitors” has emerged, providing more efficient solutions. Supercapacitors, also called electrochemical capacitors,11,12,13 they are positioned at the intersection of traditional capacitors and batteries.14 Supercapacitors show high capacitance, high power density, high efficiency, and overall high durability.5,15,16 This technology provides a power density over 20 times greater than that of traditional batteries and allows for much shorter charging and discharging times.2,17 Moreover, supercapacitors remain active longer than batteries, able to return to the original state through high charge–discharge cycles and resilience in extreme working conditions (− 40 to 80 °C).13,18 The pursuit of efficient energy storage solutions has directed significant research toward developing advanced materials for supercapacitors.

However, to fully harness their potential, the development of electrode nanomaterials with superior performance characteristics is essential.19 The effectiveness of supercapacitors is intrinsically linked to the properties of the materials used in their construction. Nanomaterials have garnered significant attention due to their remarkable electrical, physical, and electrochemical properties.20,21,22 These materials present exciting opportunities to overcome critical challenges in energy storage, such as enhancing energy density, power density, and overall device efficiency.22,23,24,25 Within this context, the synthesis and characterization of innovative electrode materials have emerged as a focal point for enhancing supercapacitor performance.

A significant advantage of nanomaterials is their high surface area to volume ratio,26,27 which facilitates enhanced interactions between the electrode and electrolyte, thereby increasing charge storage capacity and enhancing overall supercapacitor performance.13,28,29 Additionally, the tunability of nanomaterials at the atomic level allows for the optimization of supercapacitor performance by tailoring properties such as porosity, surface chemistry, and mechanical strength.5,30,31 This precise control over material characteristics opens new avenues for advancing energy storage technologies.

Based on their charge storage mechanisms, we can broadly categorize supercapacitors into electrochemical double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and pseudocapacitors.28,32,33,34,35 EDLCs rely on non-faradaic electrostatic processes, whereas pseudocapacitors utilize faradaic redox reactions, often leading to higher energy storage capacities.36,37 Among the nanomaterials exhibiting the properties mentioned above, metal oxides32 and metal chalcogenides19,21 are prominent candidates for supercapacitor fabrication. Our research highlights the potential of metal chalcogenides,38,39,40,41,42,43 including various copper selenides (CuSe, Cu2Se, Cu3Se2), as promising electrode materials due to their high electrical conductivity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness.21 Moreover, the scalable synthesis of these materials via chemical methods has led us to believe they might be a suitable fit for energy storage nanomaterials.

With their hexagonal nanostructure, klockmannite copper selenide (CuSe) nanostructures offer exceptional potential for energy storage applications.21,41,44 Despite extensive research on copper chalcogenides, a simple one-pot colloidal synthesis of CuSe remains unexplored.41 This study presents a novel approach to synthesizing klockmannite CuSe, leveraging its high surface area and abundance of active sites for enhanced electrochemical performance.

The properties of nanostructured materials, including their optical and catalytic characteristics, are significantly influenced by various factors such as size, surface area, structure, shape, solvent, and morphology.45,46 Crucially, all of these parameters are determined by the synthesis method used. Thus, the choice of synthetic route plays a vital role in tailoring the properties of nanostructured materials.47 Ndlwana et al. showed a wide observation on the different synthetic methods such as hydro/solvothermal routes, Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD), and Microwave-Assisted Synthesis.48.

Hydro/solvothermal methods require bomb reactors with Teflon lining, and the synthesis is usually carried out at high temperatures that take hours to days.41,49 In comparison, the CVD methods may be more economical and emit less waste, but they require highly intricate and expensive instrumentation.50,51,52 Additionally, even hot-injection methods involve high temperatures and typically utilize flammable or combustible materials, for which reason they require a glove box and specialized equipment, such as Schlenk lines.53,54 For these reasons, we decided to develop a rapid and straightforward one-pot synthetic method for klockmannite CuSe nano-powders, Another key factor in the supercapacitive electrode development is the electrolyte.55,56 The choice of electrolyte is crucial for supercapacitor performance, as the operational potential range is determined by the electrolyte’s electrochemical stability.57 Moreover, the electrolyte’s impact can vary depending on the nature of the electrolyte’s ions,8 ionic conductivity,58 and compatibility with the electrode material.5,59 At present, three main types of electrolytes are utilized in both research and industrial applications: aqueous electrolytes, organic electrolytes, and ionic solutions.55,59,60 Furthermore, Organic electrolytes are renowned for their ability to broaden the potential window, thereby directly boosting the energy density of a supercapacitor device.57,59.

One such organic solvent is acetonitrile (MeCN), a well-known polar solvent with a high dielectric constant and low viscosity. Recent studies have demonstrated that acetonitrile not only supports high ionic conductivity but also contributes to the stability of electrode–electrolyte interfaces in transition metal selenide systems, ultimately enhancing energy density and cycle life.18 It has been demonstrated by Xu that acetonitrile effectively stabilizes electrolyte solutions in lithium-based systems,61 a principle that translates well into supercapacitor technology. Further, Yamada et al.62 and Nilsson et al.63 have demonstrated that enhanced salt solvation in acetonitrile-based electrolytes leads to a reduction in internal resistance and an improvement in energy density in electrochemical devices. Essentially, these studies emphasize how crucial solvent-electrolyte compatibility is for optimal energy storage performance,64,65 making acetonitrile the ideal choice for advanced supercapacitors.

This research analyzes the synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation of CuSe nanoparticles as an energy storage material for supercapacitor electrodes. This work presents easily scalable CuSe synthesis, with and without carbon support. We also demonstrate the dependence of the electrochemical properties on the utilized electrolyte during electrode testing and device fabrication. The findings of this study offer valuable insights into the design of high-performance supercapacitor electrodes, with potential implications for the future of energy storage technology.

Experimental

Materials

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without additional purification. The water was purified using a Milli-Q system with a resistivity greater than 15 MΩ·cm. Copper chloride dihydrate, CuCl2∙2H2O, 99%, Selenium-powder, Se, 99.5%, and L-Ascorbic acid, 99%, were purchased from Fisher Chemicals. The carbon Blacks Black-Pearls® 2000 and Vulcan® XC-72 were purchased from Cabot, while SuperP® conductive, 99%, was purchased from Holland-Moran. Acetonitrile, MeCN, AR, and Dimethylformamide, DMF, AR, were purchased from Bio-Lab. N-Methylpyrrolidone, NMP, AR, Polyvinylidene fluoride, PVDF, AR, Sodium borohydride, NaBH4, 99%, Sodium perchlorate, NaClO4, 98%, Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate, TBABF4, 98%, and Tetraethylammonium tetrafluoroborate, TEABF4, 99%, were purchased from Thermo-Scientific. The Lithium perchlorate, LiClO4, 98%, was purchased from Alfa-Aesar, and tetraethylammonium hexafluorophosphate, TEAPF6, 98%, was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Instrumentation

Various methods and instrumentation were utilized to characterize and analyze the materials. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were captured using an Ultra-High-Resolution Field Emission SEM (Maia 3, Tescan). At the same time, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was performed using the Aztec EDS microanalytic system (Oxford Instruments) to determine material composition. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) were conducted on a JEM-2100F TEM (JEOL) operating at 200 keV equipped with a GATAN 894 US1000 camera and a GATAN 806 HAADF STEM detector. The EDS analysis was facilitated by a JEOL JEM-2100F TEM at 200 kV with an Oxford Instruments X-Max 65 T SDD detector, using a probe size of 1 nm and analyzed with AZtec software (v. 3.3) based on the standardless Cliff − Lorimer method. ImageJ software was employed for nanoparticle size and size distribution analysis using the threshold function. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using an X’pert Pro X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical) and a Bruker diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) to analyze the crystal structures of the materials. A Kβ filter 1D for Cu radiation was used with a diffraction angle (2θ) range of 20° to 80°. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using a BET surface area and pore size analyzer (TriStar II Plus, Micromeritics) at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K).

CuSe and CuSe@SP nanoparticle synthesis

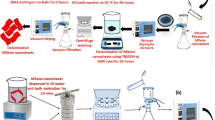

In a typical procedure, one mmol of CuCl2*2H2O was dissolved in 25 ml of DI water. To this solution, 10 mmol of L-ascorbic acid (C6H8O6, H2Asc) was added.66 A clear and transparent solution was obtained upon vigorous stirring for 10 min at 80 °C under an ambient atmosphere (this solution was labeled as solution A). Next, 0.99 mmol of elemental Se-powder was dissolved in 25 ml of DI water in the presence of a strong reducing agent, such as 1.2 mmol of NaBH4. A clear and transparent solution was obtained upon vigorous stirring of this solution for 10 min at 80 °C under an ambient atmosphere (this solution was labeled as solution B). Next, solution B was mixed with solution A. After a reaction time of 10 min, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool down naturally to room temperature. A black precipitate was obtained by washing the powder three times with DI water. Then, the participant was washed with isopropanol three more times and centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 5 min each time. Then, the powder was dried under an IR lamp for 30 min and in the oven overnight. A schematic representation of the synthesis process described in Fig. 1. In order to achieve CuSe@SP, different wt% of SP carbon have been added to solution A, before mixing (Fig. S3).

Slurry preparation and electrode fabrication

After the synthesis of CuSe and CuSe@SP nano-powders, the powders were utilized for the slurry. The preparation of slurry usually depends on the application method. In this work, we disclose two different application methods: application with an applicator and application with an air-brush.

The applicator slurry was prepared through an easy and fast procedure: 100 mg of PVDF was added to a mortar and pestle and ground with 2 ml of NMP until fully dissolved. Subsequently, 900 mg of CuSe@SP was added and mixed with an additional 6 ml of NMP. The solvent was added to the mixture gradually until an inky, shiny slurry was achieved. Following this step, the slurry was applied by a 100 μm applicator on a 7 × 16 cm aluminum foil of 20 μm width and 3.4 mg/cm2 weight. Later on, the layer was dried in the oven at 65 °C overnight. For air-brush slurry, eighty milligrams (80 mg) of PVDF were added to a glass vial, followed by 10 mL of DMF, and mixed with a magnetic stirrer. The mixture was stirred until the PVDF was fully dissolved. Then, 800 mg of the synthesized nano-powder was added and mixed for 5 min, followed by another 5 min of sonication in a sonicator bath. The resulting mixture was used immediately after sonication and was not stored. Then, the ink was air-brushed on the same-sized aluminum foil on a heated hot plate in the fume hood. The achieved mass loading of the electrodes was around ~ 4 mg/cm2. The described amounts were adjusted proportionally based on the desired mass loading.

Electrochemical testing

All the electrochemical measurements were conducted using a Potentiostat/Galvanostat (n-stat multi potentiostat, Ivium). The electrochemical performance for the supercapacitor study was carried out in a three-electrode setup. In this configuration, a carbon-coated electrode served as the working electrode (WE), with an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode (RE), and a platinum wire as the counter electrode (CE). The three-electrode system was immersed in electrolyte and carried out in ambient conditions. All the electrolytes were prepared in non-aqueous conditions with MeCN as the solvent. The electrochemical characterization of the material was performed using cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques. All the collected data were analyzed in Excel, Origin, and ZSimpWin software.

Device preparation

The above-described layers were used to prepare a symmetrical EDLC pouch device of 2 × 5 cm2 in size and with an average mass of 0.2 g. After we tested all the electrodes in various conditions, we determined the best electrolyte for the device fabrication. A device was fabricated and electrochemically tested to measure the energy and power density. A schematic description of the fabricated device can be found in Fig. 1.

Power and energy density calculations

The specific capacitance (Cs, F·g⁻1), areal capacitance (Ca, mF·cm⁻2), Energy density (Wh·kg⁻1), and power density (W·kg⁻1) were all calculated from the CV curves and GCD curves using equations previously published in the literature67 and by our group.41,42,68.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to improve clarity and enhance grammar. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Results and discussion

Nano-powder characterization of CuSe

We started our study with the optimization of the copper selenide nanoparticles (CuSe-NPs) and carbon-supported copper selenide nanocomposites (CuSe@SP-NCs) synthesis. The synthesis was carried out in different concentrations of CuCl2 and various mass percentages of SP-carbon in order to achieve the best combination. In this section, we will focus on CuSe-NPs. Figure 2 shows two SEM micrographs of the best synthesized CuSe nanoparticles. As can be seen, the nanoparticles display spherical morphology with a size of 2 nm (1.83 ± 0.41 nm). All the synthesized particles were sent for HR-TEM analysis. However, due to the particles’ unique optical properties, high magnification was found to be problematic (see Fig. S1). The microscopes measured EDS and EDX. The atomic ratios describe a 1:1 and 1:1.33 ratio of Cu to Se, respectively. In order to have a better understanding of the CuSe nanostructure, an XRD was performed. The X-ray diffraction patterns of copper selenide showed a crystalline structure of single-phase CuSe-NPs, with diffraction peaks observed at 2θ values of 26°, 28°, 31°, 46°, 50°, 56°, and 70°, which correspond to (011), (012), (006), (110), (018), (116), and (028) hkl indexes, in correlation with the literature.41,69 The observed diffraction pattern closely matched the standard diffraction pattern of klockmannite hexagonal CuSe crystals (JCPDS Card No.00–034-0171). To investigate the specific surface area of the samples, BET adsorption–desorption isotherms were performed, and the resulting curves were analyzed; a surface area of 13.0793 m2/g and pore size of 99.791 Å were found (Fig. S3).

Nano-powder characterization of CuSe@SP

Following the non-supported CuSe-NPs synthesis, we carried out the same synthesis on different types of carbon supports, such as BP2000, AC (TOB), and SUPERP. However, in this paper, we will disclose only the CuSe-SUPERP (CuSe@SP) supported particles that showed the most promising results (Fig. S2). The size and morphology of the CuSe@SP are presented in Fig. 3. The integration of spherical nanoparticles onto SP carbon transforms the morphology of CuSe@SP, yielding a more uniform, compact structure with enhanced surface area that improves electron transport and overall electrochemical performance. The EDS and EDX measured a 1:1 and 1.33:1 atomic ratio of Cu to Se, respectively. The x-ray diffraction patterns measured in this sample entirely overlap the measured peaks for non-supported CuSe-NPs, Fig. 2c. However, they show higher intensity at (006) and (110) indexes. This may be explained by stronger selectivity and preferred orientation. Usually, in layered CuSe, an enhancement of 001 (006) indicates that the crystallites are arranged in a plate-like structure along the c-axis. Additionally, the carbon support can influence the nucleation/orientation of layered chalcogenides through van der Waals forces, which boost 001 and 110 indexes.70,71 BET measurements were also conducted, and they showed a surface area of 52.6379 m2/g and a pore size of 141.562 Å (Fig. S3).

Electrochemical measurements

Following the characterization of the nanomaterials, we fabricated the electrodes using an applicator or air-brushing techniques. The applicator was found to be an easy and very cost-effective method to create layers. However, the resulting layers have been physically unstable for electrochemical use. For this reason, we chose to focus on the air-brushing technique, which is a fast and easy method to achieve highly stable electrode layers. Following the air-brushing step, no additional drying was needed, and the electrodes were ready to use. The fabricated layers were cut into 1 × 1 cm2 electrodes, and a series of electrochemical measurements were performed to identify the optimal electrolyte for our supercapacitor electrodes. All the electrochemical tests were executed in MeCN with various electrolytes, such as NaClO4, LiClO4, TBABF4, TEABF4, and TEAPF6, in three different concentrations- 0.1 M, 0.5 M, and 1.0 M.

EIS study

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis is a critical factor in studying supercapacitor electrodes. In order to investigate electrical conductivity, ionic diffusion, charge transfer mechanisms, and capacitive behavior, EIS measurements were conducted using Nyquist plots (Z'real vs. -Z"imaginary) over a frequency range of 0.01–100,000 Hz. The Nyquist plot reveals two distinct regions: a semicircular section at high frequencies and a linear region at low frequencies. This observation is indicative of the electrochemical properties of the electrodes. The equivalent electrical circuit, commonly referred to as the Randles circuit, incorporates the charge-transfer resistance, Rct, and the Warburg impedance, ZW. Based on the analysis, the impedance values of the Randles equivalent circuit can be separated into real (in-phase), Z′, and imaginary (out-of-phase), Z″ components over a wide range of frequencies.

The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot corresponds to the magnitude of the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) at the electrode surface, and it can be attributed to various factors, including (i) the electrolyte resistance within the electrode pores and (ii) the contact resistance between the electrode and the current collector. However, the resistance starting point, the electrolyte resistance (Rs), is usually related to the bulk electrolyte resistance or the equivalent series resistance (ESR). Lastly, the linear region can be attributed to ion transport limitations within the porous electrode structures, the bulk electrolyte, or nonuniform ion transport pathways from the bulk electrolyte to the porous electrode surface caused by inconsistency in electrode pore size and roughness.

A comparison between all the Nyquist plots of all the measured electrolytes can be found in Fig. 4. An EIS comparative analysis of the Rs values for all electrolytes is presented in Fig. 4. Based on these results, the electrolytes can be ordered in terms of increasing resistance as follows: TBABF4 (11.19 Ω) < LiClO4(14.34 Ω) < NaClO4(16.55 Ω) < TEABF4(20.6 Ω) < TEAPF6(23.73 Ω). It can be seen that TBABF4 shows the smallest Rs value, which means it has the smallest contact resistance between the electrode and the electrolyte. We also calculated the Rct values from the Nyquist plots and determined the order of the Rct to be as follows: TBABF4(6.21 Ω) < NaClO4(8.61 Ω) < TEAPF6(12.6 Ω) < TEABF4(14.55 Ω) < LiClO4(16.02 Ω). Additionally, from the Warburg impedance, the linear part of the plot, we can clearly indicate that BF4 ions show the best conductivity out of all the electrolytes. In comparison, PF6 and the ClO4 ions show electron or ion transport limitations and much lower conductivity. The anions radius can explain these phenomena, where BF4 ions have the lowest radius of 229 pm, ClO4 ions demonstrate a radius of 237 pm, and PF6 ions are 254 pm, the largest of the ion sizes. Further, we compared the ion solubility of the ions in MeCN, and found out the following ratio BF4- > PF6− > > ClO4−.72 It is also important to mention that the ionic solubility strongly relates to ionic mobility, and emphasizes our findings. Based on EIS measurements, it can be concluded that the size of the electrolyte ions hinders their conductivity. Among all the impedance analyses presented, it is evident that TBABF4 demonstrates superior performance as an electrolyte for CuSe@SP electrodes.

CV study

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) analysis is an essential measurement for understanding the performance of supercapacitor electrodes. CV measurements were carried out across a range of scan rates in order to explore the charge storage mechanisms, electrode reversibility, and overall electrochemical behavior. These CV results provide valuable insight into the electrode’s capacitive properties and its potential for energy storage applications. In order to produce a symmetrical EDLC device, we first evaluated the electrochemical performance of the nanocomposed electrodes in a three-electrode system using various electrolytes. The laboratory-made electrodes were used as working electrodes, with Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl saturated) as a reference electrode and platinum wire as a counter electrode.

Figure 5 represents the CV performance of the first tested electrolyte, sodium perchlorate (NaClO4). The electrodes were measured in three different scan rates, 30, 50, and 100 mV, and in three different concentrations, 0.1 M, 0.5 M, and 1.0 M. The measurements were carried out in a potential window range of − 2.5 to 1.0 V. In all three different concentrations, at least two anodic peaks are detected at − 1.5 V and 0.5 V, and at least two cathodic peaks can be seen at − 2.0 V and 0.0 V. The appearance of oxidation and reduction peaks leads us to conclude that the material shows faradaic behavior. The peaks show a broadening shape, in contrast to battery-like materials. However, when we compare all three concentrations, it becomes apparent that the higher the concentration, the broader the CV, which means the higher the specific capacitance)Fig. 6). Furthermore, a slight shift in the redox peaks can be detected; this shift can be explained by the following reasons. In low electrolyte concentrations, the electrode feels lower ionic conductivity and higher resistance. On the other hand, as the concentration increases, the resistance drops, which reduces potential loss and makes the peaks sharper and shift closer to more favourable potentials. Additionally, redox reactions in pseudocapacitors usually entail insertion/extraction of electrolyte cations.65 Consequently, in low concentrations, fewer cations are available, and this limits the kinetics.64 We can also determine that the higher the concentration of NaClO4, the greater the current range of the electrode; it is observed to be ± 0.04 A for 1.0 M.

(a) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M NaClO4 in various scan rates. (b) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M NaClO4 in various specific currents. (c) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M NaClO4 in various scan rates. (d) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M NaClO4 in various specific currents. (e) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M NaClO4 in various scan rates. (f) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M NaClO4 in various specific currents.

The second electrolyte that we tested was LiClO4, and in this case, we believed that a smaller ion could lead to more reactive reactions and faster electron transfer. However, only the experiments carried out in 0.1 M were successful )Fig. 7). The lowest concentration showed a higher potential window of − 2.5 to 1.5 V and a current range of ± 0.03 A. However, a high pill-off effect and total electrode destruction could be observed in 0.5 M and 1.0 M.

Figure 8 presents the electrochemical measurement of TBABF4, the third electrolyte. The CV curves show more pronounced pseudo-capacitive behavior, a rectangular shape with redox peaks. The potential range was measured at − 2.5 to 1.0 V, and the highest observed current range is ± 0.03 A for 0.5 M. The observed anodic peaks are at − 1.6 V and − 0.1 V, and the cathodic peaks are found at 0.2 V and − 1.75 V. It can be said that the higher the concentration, the more noticeable the redox peaks. We also can conclude from the CV and GCD curves that with the increase in concentration, higher redox peaks can be detected. These peaks can be explained by more pronounced faradaic behavior. However, in this case, the best results can be observed in 0.5 M and not in the highest concentration. When combined with the EIS results, this electrolyte shows promising characteristics for the device fabrication step.

(a) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TBABF4 in various scan rates. (b) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TBABF4 in various specific currents. (c) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TBABF4 in various scan rates. (d) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TBABF4 in various specific currents. (e) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TBABF4 in various scan rates. (f) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TBABF4 in various specific currents.

The following two electrolytes were chosen to be TEABF4 and TEAPF6 because we believed that smaller molecules may provide faster ion transfer between the electrode and the electrolyte. However, preliminary EIS testing showed higher electrolyte resistance. The electrochemical measurements for TEABF4 were conducted in a potential range of -2.5 V to 1.0 V and can be found in Fig. 9. The 0.1 M concentration showed the best pseudo-capacitive behavior out of all the concentrations. However, we can see that a 1.0 M concentration shows a bigger potential window with a higher current range of ± 0.03 A. Additionally, in this electrolyte, we can detect three redox peaks at − 1.0 to − 1.5, − 0.5 to 0.0, and 0.5–1.0 V; these peaks shift a bit with the increase in electrolyte concentration. The final electrolyte is TEAPF6. All the electrochemical results can be found in Fig. 10. In this case, the measurements were carried out in a potential window of 1.0 to − 2.5 V when the highest measured current range was 0.01 A to − 0.03 A, and as it can be seen, the current distribution was not symmetrical in contrast to all the other electrolytes. As was described previously in TEABF4, here too, three redox peaks can be detected at the same voltage. However, in this case, the anodic peaks are more pronounced than the cathodic ones.

(a) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TEABF4 in various scan rates. (b) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TEABF4 in various specific currents. (c) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TEABF4 in various scan rates. (d) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TEABF4 in various specific currents. (e) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TEABF4 in various scan rates. (f) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TEABF4 in various specific currents.

(a) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TEAPF6 in various scan rates. (b) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.1 M TEAPF6 in various specific currents. (c) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TEAPF6 in various scan rates. (d) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 0.5 M TEAPF6 in various specific currents. (e) CV curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TEAPF6 in various scan rates. f) GCD curves of CuSe@SP electrode in 1.0 M TEAPF6 in various specific currents.

A full comparison between all the electrolytes and their concentrations can be found in Fig. 11. As it can be concluded, the resulting cyclic voltammograms exhibit a rectangular shape with redox peaks, indicating pseudo-capacitive behavior. At higher scan rates, the retention of this shape suggests efficient charge transfer and rapid ionic diffusion within the electrode material. However, it is also important to mention that not all the electrolytes show symmetrical current division, which is crucial for GCD.

GCD study

Galvanostatic Charge–Discharge is a fundamental technique used to evaluate the performance of supercapacitor electrodes. By applying a constant current to an electrode and monitoring its voltage over time, researchers can determine key characteristics, such as specific capacitance, energy density, and power density. This method is particularly valuable for understanding the behavior of different electrode materials and optimizing their performance for specific applications. Additionally, galvanostatic charge–discharge can be used to assess the electrode’s stability over multiple cycles, providing insights into its long-term durability. Additionally, the specific capacitance of the electrodes, with an active area of 1 cm2 immersed in the electrolyte, was calculated from the CV curve using the following equation.

In this equation, 'Cs' represents the specific capacitance (F·g⁻1), 'V' is the potential sweep rate (mV·s⁻1), (Vc—Va) denotes the operational potential window, 'I' is the current response (mA), and 'm' is the mass of the deposited electrode material. Additionally, we calculated the capacitance, energy density, and power density.

The results of the GCD cycles at different current densities of all the electrolytes are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. Each charging and discharging cycle shows non-linear behavior. No perfect rectangular shape is observed, which suggests a non-faradaic material nature.

Specific capacitance values were calculated using established equations, with the corresponding specific capacitance values shown in Fig. 12. Notably, a reduction in current density led to an increase in specific capacitance, primarily due to reduced electrolyte ion diffusion resulting from time limitations. At a current density of 4 A·g−1, the GCD curve exhibited the highest capacitance value of ~ 75 F·g−1 for LiClO4 electrolyte. When looking at higher current densities, TBABF₄ seems to keep more of its low-rate capacitance compared to ClO₄⁻ electrolytes. This aligns with its lower Rs/Rct seen in the EIS data. Consequently, this clarification serves to reconcile the apparent discrepancy between the resistance rankings obtained from EIS and the measured low-rate capacitance values. Furthermore, the lowest capacitance over all three concentrations was of the TEAPF6 electrolyte. However, the specific capacitance can be arranged in the following order: ClO4 group > BF4 group > PF6 group.

The current density (A·g−1) vs. specific capacitance (F·g−1) of (a) the ClO4 electrolytes group in various concentrations, (b) the TBABF4 electrolytes group in various concentrations, (c) the TEABF4 electrolytes group in various concentrations, and (d) the TEAPF6 electrolytes group in various concentrations.

Energy and power density results

Upon performing calculations of energy density, power density, and coulombic efficiency, the following conclusions were drawn: perchlorate-based electrolytes exhibited the highest energy density and power density, with LiClO₄ achieving 187.4 Wh·kg−1 and 5291.0 W·kg−1, respectively. However, these electrolytes demonstrated the lowest stability. The next best-performing electrolyte, TBABF₄, yielded optimal results at a concentration of 0.5 M, with an energy density of 102 Wh·kg−1 and a power density of 1091.3 W·kg−1. Despite these favorable characteristics, TBABF₄ displayed the lowest energy density among all the electrolytes studied. The TEA-based electrolytes did not present notable results in terms of either energy density or power density. The Coulombic efficiency for most electrolytes was approximately 100% or higher, indicating that charging and discharging times were nearly equivalent. Notably, a coulombic efficiency exceeding 100% suggests a discharge time longer than the charging time, a highly desirable feature for supercapacitors.

Device electrochemical testing

A symmetrical EDLC supercapacitor device was prepared in order to confirm the ultimate CuSe@SP electrode performance. The device was fabricated according to Fig. 13 and tested electrochemically after we found and analyzed the best conditions for these measurements. Based on the previously presented results, the chosen electrolyte for this device was 1.0 M TBABF4 (Fig. S4). However, the resulting specific measured capacitance overall current densities was 1 F·g⁻1, an interesting characteristic, however, not a good behavior for a supercapacitor. According to these results, it is apparent that further work has to be done in order to achieve a better understanding of the CuSe@SP supercapacitors and their electrochemical properties. Furthermore, much more testing has to be done in order to understand the variety of parameters that may influence this measurement.

Conclusions

This paper presents a rapid and straightforward one-pot synthesis of CuSe. The significance of these findings lies in the development of a novel and accessible approach to synthesizing CuSe nanoparticles, which has the potential to drastically advance the field of nanomaterials . In contrast to established one-pot pathways described in literature and industry, our synthesis does not require any special lab equipment, such as hydrothermal bombs or silar systems. Our synthesis can be completed in 30 min, including washing, making it less time-consuming than the previously mentioned methods. It is also important to mention that our synthesis is easily scalable for industrial use. Furthermore, this synthesis consistently provides 2 nm nanoparticles with klockmannite hexagonal CuSe crystals and can be conducted quickly and efficiently on any provided carbon support. In the realm of nanomaterials, it is widely recognized that smaller particles possess a greater number of active sites, which is a crucial factor in the advancement of supercapacitor electrodes.

Based on the electrochemical testing, our results also reveal that the electrolyte TBABF₄ exhibits the lowest overall resistance, with an Rs of 11.19 Ω and an Rct of 6.21 Ω, outperforming LiClO₄, NaClO₄, TEABF₄, and TEAPF₆. These findings indicate that TBABF₄ facilitates superior ion transport and lower charge-transfer resistance, which are key factors in achieving higher specific capacitance. This finding clearly suggests that employing smaller anions in supercapacitor designs could enhance ion transport and overall performance.

In the evaluation of various electrolytes, LiClO₄ at a concentration of 0.1 M exhibits the highest low-rate energy density, measuring at 187.4 Wh kg⁻1. However, its performance is compromised by a lack of stability at elevated concentrations. In contrast, TBABF₄ at 0.5 M demonstrates a superior balance between stability, rate capability, and operational window, making it the optimal choice for practical devices that prioritize durability and power output. Thus, while LiClO₄ may be advantageous for applications requiring short-duration, low-rate energy scenarios at conservative potentials, TBABF₄ emerges as the preferred electrolyte for applications demanding sustained performance and reliability.

Additionally, the results indicate that, an increase in concentration correlates with elevated values of all other measured parameters. The performance of electrolytes shows a complex, non-monotonic relationship with concentration, influenced by the specific type of salt used. This behavior arises from competing factors, namely viscosity and ion pairing, which can both significantly affect the overall performance. As a result, each electrolyte has a distinct optimal concentration at which its effectiveness is maximized. non-monotonically with concentration in a salt-specific manner due to opposing trends in viscosity and ion-pairing; each electrolyte exhibits its own optimum. Furthermore, the ion radius shows an immense contribution to the ion transfer rates, especially the negative anion size. In this study, the smallest anions demonstrated superior results compared to their counterparts. However, further work has to be done to determine the real role of the cations; several studies have been conducted on the subject that demonstrate a line of reasoning similar to our conclusions.73.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, J. & Azam, W. Natural resource scarcity, fossil fuel energy consumption, and total greenhouse gas emissions in top emitting countries. Geosci. Front. 15, 101757 (2024).

Castro-Gutiérrez, J., Celzard, A. & Fierro, V. Energy storage in supercapacitors: Focus on tannin-derived carbon electrodes. Front. Mater. 7, 1–25 (2020).

Rajagopal, S., Pulapparambil Vallikkattil, R., Mohamed Ibrahim, M. & Velev, D. G. Electrode materials for supercapacitors in hybrid electric vehicles: Challenges and current progress. Condens. Matter 7, 6 (2022).

Donaghy, T. Q., Healy, N., Jiang, C. Y. & Battle, C. P. Fossil fuel racism in the United States: How phasing out coal, oil, and gas can protect communities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 100, 103104 (2023).

Sharma, S. & Chand, P. Supercapacitor and electrochemical techniques: A brief review. Results Chem. 5, 100885 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Spray-painted binder-free snse electrodes for high-performance energy-storage devices. Chemsuschem 7, 308–313 (2014).

Islam, M. S., Mubarak, M. & Lee, H. J. hybrid nanostructured materials as electrodes in energy storage devices. Inorganics 11, 1–7 (2023).

Khan, A. U. et al. A new cadmium oxide (CdO) and copper selenide (CuSe) nanocomposite: An energy-efficient electrode for wide-voltage hybrid supercapacitors. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 656, 130327 (2023).

Packiaraj, R., Devendran, P., Venkatesh, K. S., Mahendraprabhu, K. & Nallamuthu, N. Unveiling the structural, charge density distribution and supercapacitor performance of NiCo2O4 nano flowers for asymmetric device fabrication. J. Energy Storage 34, 102029 (2021).

Karuppanan, K. K., Panthalingal, M. K. & Biji, P. Nanoscale, Catalyst Support Materials for Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications 468–495 (Elsevier, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813351-4.00027-4

Pandolfo, T., Ruiz, V., Sivakkumar, S. & Nerkar, J. General Properties of Electrochemical Capacitors. In Supercapacitors pp. 69–109 (Wiley, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527646661.ch2

Graś, M., Kolanowski, Ł, Wojciechowski, J. & Lota, G. Electrochemical supercapacitor with thiourea-based aqueous electrolyte. Electrochem. commun. 97, 32–36 (2018).

Ndiaye, N. M. et al. High-performance asymmetric supercapacitor based on vanadium dioxide and carbonized iron-polyaniline electrodes. AIP Adv. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Dave, P. N. & Gor, A. Natural Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels and Nanomaterials. In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications 36–66 (Elsevier, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813351-4.00003-1

Merabet, L., Rida, K. & Boukmouche, N. Sol–gel synthesis, characterization, and supercapacitor applications of MCo2O4 (M = Ni, Mn, Cu, Zn) cobaltite spinels. Ceram. Int. 44, 11265–11273 (2018).

Pandit, B. et al. Two-dimensional hexagonal SnSe nanosheets as binder-free electrode material for high-performance supercapacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35, 11344–11351 (2020).

Şahin, M. E., Blaabjerg, F. & Sangwongwanich, A. A comprehensive review on supercapacitor applications and developments. Energies 15, 1–26 (2022).

Theerthagiri, J. et al. Recent advances in metal chalcogenides (MX; X = S, Se) nanostructures for electrochemical supercapacitor applications: A brief review. Nanomaterials 8, 256 (2018).

Kundu, S., Yi, S. I. & Yu, C. Gram-scale solution-based synthesis of SnSe thermoelectric nanomaterials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 459, 376–384 (2018).

Štůsková, K. et al. The in vitro effects of selected substances and nanomaterials against Diaporthe eres, Diplodia seriata and Eutypa lata. Ann. Appl. Biol. 182, 226–237 (2023).

Mata-Padilla, J. M. et al. Synthesis and superficial modification “in situ” of copper selenide (Cu2−x Se) nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. Nanomaterials 14, 1151 (2024).

Terna, A. D., Elemike, E. E., Mbonu, J. I., Osafile, O. E. & Ezeani, R. O. The future of semiconductors nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 272, 115363 (2021).

Avasthi, P., Kumar, A. & Balakrishnan, V. Aligned CNT forests on stainless steel mesh for flexible supercapacitor electrode with high capacitance and power density. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 1484–1495 (2019).

Mahesh, M., Kumar, K. V., Abebe, M., Udayakumar, L. & Mathankumar, M. A review on enabling technologies for high power density power electronic applications. Mater. Today Proc. 1(46), 3888–3892 (2021).

Zhao, L. SnSe/SnS: Multifunctions beyond thermoelectricity. Mater. Lab 1, 1–20 (2022).

Sermiagin, A., Meyerstein, D., Bar-Ziv, R. & Zidki, T. The chemical properties of hydrogen atoms adsorbed on M°-nanoparticles suspended in aqueous solutions: the case of Ag°-NPs and Au°-NPs reduced by BD₄¯. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 57, 16525–16528 (2018).

Otowa, T., Tanibata, R. & Itoh, M. Production and adsorption characteristics of MAXSORB: High-surface-area active carbon. Gas Sep. Purif. 7, 241–245 (1993).

Mei, B. A., Munteshari, O., Lau, J., Dunn, B. & Pilon, L. Physical interpretations of nyquist plots for EDLC electrodes and devices. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 194–206 (2018).

Karuppasamy, K. et al. Unveiling a binary metal selenide composite of CuSe polyhedrons/CoSe2 nanorods decorated graphene oxide as an active electrode material for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 131535 (2022).

Yu, B. et al. Self-assembled pearl-bracelet-like CoSe2–SnSe2 /CNT hollow architecture as highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 1655–1662 (2018).

Isotta, E. et al. Effect of Sn oxides on the thermal conductivity of polycrystalline SnSe. Mater. Today Phys. 31, 100967 (2023).

Malavekar, D. B. et al. Synthesis of layered copper selenide on reduced graphene oxide sheets via SILAR method for flexible asymmetric solid-state supercapacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 869, 159198 (2021).

Böckenfeld, N., Jeong, S. S., Winter, M., Passerini, S. & Balducci, A. Natural, cheap and environmentally friendly binder for supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 221, 14–20 (2013).

Samynaathan, V., Iyer, S. R., Kesavan, K. S. & Michael, M. S. High-performance electric double-layer capacitor fabricated with nanostructured carbon black-paint pigment as an electrode. Carbon Lett. 31, 137–146 (2021).

Dai, S., Lin, Z., Hu, H., Wang, Y. & Zeng, L. 3D printing for sodium batteries: From material design to integrated devices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, (2024).

Muzaffar, A., Ahamed, M. B., Deshmukh, K. & Thirumalai, J. A review on recent advances in hybrid supercapacitors: Design, fabrication and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 101, 123–145 (2019).

Pazhamalai, P., Krishnamoorthy, K. & Kim, S. J. Hierarchical copper selenide nanoneedles grown on copper foil as a binder free electrode for supercapacitors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 14830–14835 (2016).

Jadhav, C. D., Patil, G. P., Lyssenko, S. & Minnes, R. Hot-injected ligand-free SnTe nanoparticles: A cost-effective route to flexible symmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 13(4), 2822–2835 (2025).

Jadhav, C. D., Patil, G. P., Amar, M., Lyssenko, S. & Minnes, R. Unveiling potential of SnS nanoflakes: A flexible solid-state symmetric supercapacitive device. J. Power Sour. 623, 235496 (2024).

Jadhav, C. D., Patil, G. P., Lyssenko, S., Borenstein, A. & Minnes, R. Electrolyte-dependent performance of SnSe nanosheets electrode for supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 94, 112364 (2024).

Patil, G. P., Jadhav, C. D., Lyssenko, S., Borenstein, A. & Minnes, R. Exploring one-pot colloidal synthesis of klockmannite CuSe nanosheet electrode for symmetric solid-state supercapacitor device. J. Mater. Chem. C 12, 14404–14420 (2024).

Patil, G. P., Jadhav, C. D., Lyssenko, S. & Minnes, R. Hydrothermally synthesized copper telluride nanoparticles: First approach to flexible solid-state symmetric supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155284 (2024).

Dutta, A. et al. 1D transition-metal dichalcogenides/carbon core-shell composites for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 21806–21816 (2023).

Shitu, I. G. et al. X-ray diffraction (XRD) profile analysis and optical properties of Klockmannite copper selenide nanoparticles synthesized via microwave assisted technique. Ceram. Int. 49, 12309–12326 (2023).

Kelly, K. L., Coronado, E., Zhao, L. L. & Schatz, G. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: The influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. Chart 107, 668–677 (2003).

Liu, Q., Zhang, A., Wang, R., Zhang, Q. & Cui, D. A review on metal- and metal oxide-based nanozymes: Properties, mechanisms, and applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 154 (2021).

Ndolomingo, M. J., Bingwa, N. & Meijboom, R. Review of supported metal nanoparticles: Synthesis methodologies, advantages and application as catalysts. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 6195–6241 (2020).

Ndlwana, L. et al. Sustainable hydrothermal and solvothermal synthesis of advanced carbon materials in multidimensional applications: A review. Materials. 14, 5094 (2021).

Jadhav, C. D., Patil, G. P., Lyssenko, S. & Minnes, R. Hot-injected ligand-free SnTe nanoparticles: A cost-effective route to flexible symmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ta07111e (2024).

Cuenya, B. R. & Behafarid, F. Nanocatalysis: Size-and shape-dependent chemisorption and catalytic reactivity. Surf. Sci. Rep. 70(2), 135–187 (2015).

Chatterjee, S. Heavy fermion thin films: Progress and prospects. Electron. Struct. 3(4), 043001 (2021).

Kwon, H. et al. Ultra-pure nanoporous gold films for electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 13, 11656–11665 (2023).

Lyssenko, S., Amar, M., Sermiagin, A. & Minnes, R. Carboxylic ligands and their influence on the structural properties of PbTe quantum dots. PLoS ONE 20, 1–15 (2025).

Lyssenko, S., Amar, M., Sermiagin, A., Barbora, A. & Minnes, R. Tailoring PbTe quantum dot Size and morphology via ligand composition. Sci. Rep. 15, 18–21 (2025).

Zhi, M., Xiang, C., Li, J., Li, M. & Wu, N. Nanostructured carbon-metal oxide composite electrodes for supercapacitors: A review. Nanoscale 5, 72–88 (2013).

Tang, G., Liang, J. & Wu, W. Transition metal selenides for supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 1–29 (2024).

Ramachandran, R. & Wang, F. Electrochemical capacitor performance: Influence of aqueous electrolytes. In Supercapacitors—Theoretical and Practical Solutions 51–68 (InTech, 2018). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70694

Liu, Q., Zhang, S. & Xu, Y. Two-step synthesis of CuS/C@ PANI nanocomposite as advanced electrode materials for supercapacitor applications. Nanomaterials 10(6), 1034 (2020).

Frackowiak, E. Carbon materials for supercapacitor application. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 1774–1785 (2007).

Alrousan, S. et al. Nickel–cobalt oxide nanosheets asymmetric supercapacitor for energy storage applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 1–10 (2023).

Xu, K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104, 4303–4418 (2004).

Yamada, Y. et al. Unusual stability of acetonitrile-based superconcentrated electrolytes for fast-charging lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5039–5046 (2014).

Nilsson, V., Younesi, R., Brandell, D., Edström, K. & Johansson, P. Critical evaluation of the stability of highly concentrated LiTFSI—Acetonitrile electrolytes vs. graphite, lithium metal and LiFePO4 electrodes. J. Power Sour. 384, 334–341 (2018).

Dai, S., Yang, C., Wang, Y., Jiang, Y. & Zeng, L. In situ TEM studies of tunnel-structured materials for alkali metal-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 12, 1–34 (2025).

Zhang, K. et al. Reaction mechanism and structural evolution of tunnel-structured KCu7S4 Nanowires in Li+/Na+-Ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 1–9 (2024).

Pejjai, B., Reddy, V. R., Seku, K., Pallavolu, M. R. & Park, C. Eco-friendly synthesis of SnSe nanoparticles: Effect of reducing agents on the reactivity of a Se-precursor and phase formation of SnSe NPs. New J. Chem. 42(7), 4843–4853 (2018).

Landi, G. et al. A comparative evaluation of sustainable binders for environmentally friendly carbon-based supercapacitors. Nanomaterials 12(1), 46 (2021).

Feng, Z. et al. Solution processed 2D SnSe nanosheets catalysts: Temperature dependent oxygen reduction reaction performance in alkaline media. J. Electroanal. Chem. 916, 116381 (2022).

Yewale, M. A. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of CuS x Se 1−x thin film for supercapacitor application. J. Alloys Compd. 754, 56–63 (2018).

Liu, Y. Q. et al. Facile microwave-assisted synthesis of klockmannite CuSe nanosheets and their exceptional electrical properties. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–8 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Vertically oriented and interpenetrating CuSe nanosheet films with open channels for flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2, 1089–1096 (2017).

Perera, A. S. et al. Decoding the effect of anion identity on the solubility of N-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl)phenothiazine (MEEPT). Energy Fuels 39, 10649–10658 (2025).

Gittins, J. W. et al. Understanding electrolyte ion size effects on the performance of conducting metal−organic framework supercapacitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12473–12484 (2024).

Acknowledgements

AS is thankful to Ariel University for the postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. S.L. Data curation, Methodology. A.B. Data curation, H.P. Data curation. A.B. Supervision. R.M. Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sermiagin, A., Lyssenko, S., Barbora, A. et al. One pot synthesis of klockmannite CuSe nanoparticles for supercapacitors and the electrolyte role. Sci Rep 15, 40236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24042-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24042-3