Abstract

A novel nanocomposite electrode, PANI-MOF5@SBA-15-NH2, was successfully fabricated by sequential functionalization of mesoporous SBA-15 silica with APTES and MOF5, followed by polyaniline coating via oxidative polymerization. The electrode exhibited excellent electrochemical performance, including a high specific capacitance of 757 F/g at 1 A/g, outstanding cycling stability with 98.8% capacitance retention after 8000 cycles, and a coulombic efficiency exceeding 100%. Additionally, it achieved an energy density of 27 W h/kg and a power density of 128 W/kg. These improvements result from the synergistic effects of high surface area, enhanced conductivity, and abundant electroactive sites. The composite shows strong potential for advanced supercapacitor applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the wake of increasing environmental issues and the necessity of using sustainable energy resources in response to the current energy crises, renewable energy sources like solar and wind energy have garnered significant research in the last few decades. Although promising renewable energy resources, these sources have limitations due to their intermittent nature and limited usage times, and hence require efficient energy storage systems to support continuous energy availability1,2,3,4,5. Supercapacitors have surfaced as potential options for future energy storage devices with high power density, fast discharge-charge times, extended life cycles, and environmentally friendly nature6,7,8. Recent technological advances in supercapacitors have been aimed at optimizing electrode materials to increase energy density at the expense of power density and cyclability of electrodes9,10.

Supercapacitors are generally classified as electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and pseudocapacitors according to their mechanism of charge storage. EDLCs take advantage of electrostatic adsorption/desorption of ions at the electrode/electrolyte interface via carbonaceous materials such as activated carbon, graphene derivatives, and high-surface-area and tunable porosity carbons. On the other hand, pseudocapacitors utilize rapid and reversible Faradaic redox processes of metal oxides, conducting polymers, and ionic liquids with higher capacitance but usually at the expense of cycling stability11,12.Recent works have proven that the integration of several classes of materials into hybrid electrodes greatly improves overall electrochemical performance through synergistic integration of their benefits13,14,15,16,17. For instance, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with their adjustable porosity structures, high specific area, and chemical flexibility have gained much interest as precursors or building blocks for electrodes of supercapacitors. Of MOFs, the ZnO nodes and 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate linkages of MOF-5 stand out due to their highly porous structure and capacity for facilitating the transport of ions to yield higher capacitance and rate performance18,19,20,21. In addition, mesoporous materials of silica like SBA-15 have found growing interest as structural scaffolding and templates for energy storage due to their large surface area, hydrothermal stability, and homogeneous pore sizes. Functionalization of SBA-15 using nitrogen-functional groups (such as amines) has been shown to increase electrical conductivity and enhance redox kinetics upon integration with pseudocapacitive materials. Interestingly, nitrogen-doping has been found to enhance charge transfer and wetting at the electrode-electrolyte interface and hence capacitance and cyclability22,23,24,25,26. Conductive polymers like polyaniline (PANI) and polypyrrole remain popular due to their high theoretical capacitance and ease of synthesis27,28,29,30,31. However, their limited mechanical and electrochemical stability during prolonged cycling has prompted researchers to design composite electrodes combining conductive polymers with MOFs and functionalized mesoporous supports32,33,34. Recent works highlight PANI-MOF composites supported on SBA-15-NH2 as a promising architecture, offering abundant active sites, efficient ion diffusion pathways, and enhanced cyclic durability35,36.

Despite these advances, challenges persist in achieving optimal synergy among the components to balance high capacitance, rate capability, and long-term stability under practical operating conditions. Hence, the present study focuses on the synthesis and electrochemical evaluation of a novel PANI-MOF5@SBA15-NH2 nanocomposite electrode, aiming to address the existing research gap in developing highly stable, high-capacitance electrodes suitable for symmetric supercapacitors. This approach leverages the structural robustness of SBA-15, the porosity and tunability of MOF-5, and the pseudocapacitive properties of PANI to deliver enhanced energy storage performance.

Materials and methods

Materials

Pluronic P123 (PEO20–PPO70–PEO20; Mr = 5800), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 98%), (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (H2N(CH2)3Si(OCH2CH3)3, ≥ 98.0%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37 wt%), zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn (NO3)2·6H2O), 98%), ammonium persulfate (APS, 98%), and 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (BDC, 98%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Aniline (C6H5NH2, ≥ 99.5%), toluene (C6H5CH3, ≥ 99.9%), dimethylformamide (DMF, 96%), and dichloromethane (DCM, ≥ 99.8%) were acquired from Merck. Deionized (DI) water was used to prepare aqueous solutions.

Synthesis of SBA-15

In a conventional procedure to prepare highly structured mesoporous SBA-15, triblock copolymer Pluronic P123 (4 g) was first mixed into purified water (30 mL). Then, HCl (2 M, 120 mL) was introduced to the mixture, which was then continuously stirred for 2 h under ambient conditions. Following this step, tetraethyl orthosilicate (8.5 g) was incorporated into the solution and stirred for a duration of 20 h at 30 °C. The resultant blend remained undisturbed at 80 °C for a duration of 24 h. The solid MS product was subjected to filtration, followed by multiple washing cycles, and left to dry thoroughly at ambient conditions overnight. Then, the obtained material was calcined at 550 °C for six hours, using a temperature ramp of 2 °C per minute37,38,39,40,41,42.

Synthesis MS-NH2

For the preparation of MS-NH2, pristine hexagonal-silica (MS) (3 g) from the previous step was dispersed in 100 mL of dry toluene. Under a nitrogen atmosphere and continuous stirring, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (2.43 g, 11 mmol) was added, and the mixture was refluxed for 48 h at 110 °C. Upon completion of the reaction, the resulting white precipitate was successively washed with 100 mL of hexane and 100 mL of dichloromethane. The final solid white powder product (MS-NH2) was dried under vacuum at room temperature for 12 h43.

Synthesis of MOF5@MS-NH2

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (360 mg, 1.21 mmol) was initially dissolved in 40 mL of DMF, along with 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate (66 mg, 0.4 mmol), under sonication. Subsequently, MS-NH2 (36 mg) was added to the solution, and the mixture was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave (80 mL capacity) and heated in an oven at 100 °C for 36 h. After cooling, the product was filtered and washed three times with DMF and ethanol, respectively. Finally, the sample was dried at 65 °C under high vacuum.

Synthesis of PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2

For the polymerization process, MOF5@MS-NH2 (1.5 g) was initially suspended in 100 mL of 1 M HCl containing 0.5 M aniline for 30 min under ultrasonic conditions. Subsequently, a dropwise addition of APS (50 mL, 1.1 M) solution was carried out over 30 min while the solution was stirred. Following 4 h of uninterrupted stirring, the mixture was filtered, rinsed in acetone and water four times, then subjected to vacuum drying at 90 °C for a full day.

Fabrication of the working electrode

The electrochemical properties of PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 for use as a high-performance electrode in supercapacitors were assessed. To create the electrode, a mixture containing 10 wt% acetylene black, 85 wt% of the active components, and 5 wt% polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) binder was blended in 20 mL of N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) to form a slurry. Subsequently, the slurry weighed about 3 mg and was applied to a 1 cm2 Carbon sheet and allowed to dry in a vacuum oven set at 90 °C for 8 h. A conventional three-electrode configuration was used, comprising a carbon sheet, platinum, and an Ag/AgCl electrode (KCl, 3 M), serving as the working, counter, and reference electrodes, respectively. All electrochemical evaluations were conducted in an H2SO4 solution (1 M) as the electrolyte. The electrochemical properties and effectiveness of the synthesized sample were evaluated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD), and cyclic voltammetry (CV) on an Autolab PGSTAT 204. EIS measurements were performed under open circuit conditions, utilizing an AC voltage of 5 mV over a frequency span from 100 kHz to 10 mHz. Specific capacitance (CS), energy, and power densities were derived from the charge/discharge profiles based on Eqs. (1–3)44:

where I, Δt, m, ΔV, P (W/kg), and E (Wh/kg) denote the fixed discharge current (A), duration of discharge, mass of the active material (g), voltage range (V), energy, and power, respectively.

Characterization

The morphology of the electrode components was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, VEGA3 TESCAN), energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) (Philips model X130), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi 200 kV). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was done using a Thermo Scientific device (model: Nicolet iS10, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis to identify the phase composition and crystal structure was performed with a Rigaku diffractometer (MiniFlex600, USA). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method measured surface area and porosity using a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 at a cryogenic temperature of -196 °C.

Results and discussion

Characterization of PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite

In Fig. 1, the different steps of the fabrication of the composite are illustrated. These steps are composed of the synthesis of MOF5@MS-NH2 and then the polymerization of MOF5@MS-NH2 with aniline. As shown in Fig. 1, MS was synthesized via tetraethyl orthosilicate and P123 at the first step, then modified with APTES and MOF5 to prepare MS-NH2 and MOF5@MS-NH2, respectively. Then, PANI chains with great electrical conductivity were uniformly coated on the surface of MOF5@MS-NH2, resulting in the production of the final composite PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite.

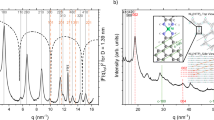

FT-IR spectroscopy was used to confirm the chemical structures of MS-NH2, MOF5@MS-NH2, and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2a, the FT-IR spectra of MS exhibits distinct peaks representative of the condensed silica network, featuring bands at 463, 800 and 1197 cm− 1, which align with the asymmetric/symmetric vibrations of Si–O–Si bonds. Furthermore, a band at 950 cm− 1 signifies the presence of Si–OH groups. Notably, the significant vibration peak at 1636 cm− 1 in the spectra of MS is attributed to physically adsorbed water molecules45. After APTES treatment, the FT-IR spectrum of MS-NH2 exhibits stretching vibrations of amino groups at 1499 and 1572 cm− 1, confirming the grafting of amino groups onto the silica surface46. The FT-IR spectra of MOF5@MS-NH2 show clear peaks at 1578 and 1384 cm− 1, which correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C–O linkage associated with Zn. Moreover, several weak peaks observed in the range of 1200–870 cm− 1 indicate the in-plane bending vibrations of the C–H bond within the BDC’s benzene ring. Similarly, the smaller peaks within the 820–670 cm− 1 range are attributed to the out-of-plane bending motions of the C–H bond in the BDC’s benzene ring. Notably, the 537 cm− 1 peak signifies the Zn–O stretching of the Zn4O cluster47. For PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2, the observed spectra reveal distinct absorption bands at 797, 1300, 1467, 1575, 3050, and 3210 cm− 1, which are indicative of PANI’s characteristic absorption features. The peak at 3050 cm− 1 is related to the stretching vibration of the C–H aromatic band, and the broad band at 3210 cm− 1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of N–H48,49. Figure 2b shows the expanded spectrum of MOF5@MS-NH2 and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2.

The confirmation of the ordered mesoporous structure was conducted through low-angle XRD, as illustrated in Fig. 2c. In all samples, three distinct diffraction peaks were observed: a prominent peak at 2θ = 0.94°, accompanied by two less intense peaks at 1.58° and 1.83°. These peaks, denoting (100), (110), and (200) diffraction, respectively, indicate the presence of a characteristic 2D hexagonal (P6mm) symmetry and a systematically arranged pore structure50. MS-NH2 displays three distinct peaks at (100), (110), and (200), indicating a meticulously organized 2D hexagonal mesostructure. The findings affirm that the structured mesoporous arrangement remains intact even after undergoing modification with MOF5; in addition, a peak at 6.8° also appeared due to MOF551. Nevertheless, the peak intensity at (100) for SBA-15 notably diminished as the amount of PANI increased, attributed to the polymer being incorporated within the channels52.

Figure 2d presents the wide-angle XRD spectrum of the synthesized MOF5@MS-NH2 and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 composites. In the XRD pattern of MOF5@MS-NH2, the three main diffraction peaks at 9.7°,13.7°, and 15.4° are related to MOF5. Following polymerization, a reduction in the intensity of MOF5@MS-NH2 characteristic peaks is observed. Notably, three peaks emerge at 2θ angles, approximately 14.2°, 19.8°, and 25.6°, representing the distinctive peaks of PANI53.

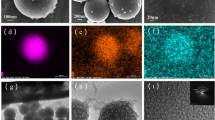

In Fig. 3, the SEM images depict the morphologies of MS, MOF5@MS-NH2, and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH254. The pristine MS (Fig. 3a) displays distinctive wheat-like formations of densely packed aggregates made up of uniformly sized short-rod domains. This structure is recognized for its extended parallel channels arranged in a 2D-hexagonal pattern55. In Fig. 3b, it is evident that MS nanoparticles are situated on the cubic structures of MOF556. After the polymerization reaction, PANI formed plate-like structures in certain areas, while functionalization with PANI occurred both inside the pores and outside the MS in other areas (Fig. 3c)57. According to the TEM analysis of the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 configuration, as depicted in Fig. 3d, it is postulated that the incorporation of MOF5 and PANI within the mesoporous channels of MS may serve as a mechanism for fortifying the structural integrity of the MOF5 framework. In contrast, the illustration of PANI distributions along the external facets of MS channels reveals that aniline polymerization takes place both inside the pores and on the exterior surface of the MS material58.

Two complementary analytical techniques, namely elemental analysis and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), were employed to accurately characterize the composition of a synthesized ternary composite consisting of PANI, amine-functionalized SBA-15 (SBA-15-NH2), and a zinc-containing metal–organic framework (MOF5). The results, which are presented in Table 1; Fig. 4, provide strong evidence for the successful integration of all components within the composite.

Elemental analysis revealed the expected weight percentages of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen, confirming the incorporation of the constituents including polyaniline, SBA15-NH2, and the MOF5. To validate the presence of additional elements, EDX spectroscopy was conducted. The EDX spectra clearly indicated the presence of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, silicon, and zinc. These elements can be attributed to specific components. The carbon is from PANI, SBA15-NH2, and MOF5. The nitrogen is from both PANI and the SBA15-NH2. The silicon is from the SBA15-NH2 while the oxygen is from the SBA15-NH2 and MOF5. The zinc from the MOF5. A minor chlorine signal was also observed, likely originating from residual precursors or reagents used during synthesis.

So, the results from elemental analysis and EDX confirm the successful synthesis of the ternary composite (PANI-MOF5@MSNH2) and the uniform distribution of its constituent components. The consistency of these findings across both techniques offers a robust validation of the composite’s structural integrity and compositional accuracy.

Figure 5a presents the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms for MS and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 at 77 K59. Both samples demonstrate a type IV isotherm with a type H1 hysteresis loop, characteristic of materials with one-dimensional cylindrical pores and capillary condensation phenomena. This behavior aligns with the classification of mesoporous materials according to IUPAC standards. The pore size distribution profiles of MS and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2, determined via the BJH method, are illustrated in Fig. 5b. The curves reveal mesoporous that are both consistent in size and narrow. The pore diameter (dp), specific surface area (SBET), total pore volume (VP), and pore wall thickness (bp) of MS and PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 were calculated. The BET specific surface area, pore volume, pore diameter, and pore wall thickness of the intact mesoporous silica SBA-15 were 725 m2g− 1, 6 nm, 1.1 cm3g− 1and 23.11 Å, respectively.

Meanwhile, for PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2, it was 330 m2g− 1, 6.7 nm, 0.57 cm3g− 1, and 28.7 Å. These results show that incorporating MOF5 and PANI inside the pores and on the surface of the MS-NH2 has reduced the pore volume and surface area and increased the pore wall thickness and pore diameter of the final porous composite. The obtained results can be found in Table 2. This mesoporous configuration facilitates the effective interaction between the electrode substance and the electrolyte, thereby enabling the efficient transfer of electrons and ions39.

Electrochemical characteristics for supercapacitor applications

The CV performance of the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite on a Carbon sheet was explored using 1 M H2SO4 as the electrolyte. The CV analysis was conducted within a potential window of − 0.2 to 0.8 V at varying scan rates of 5, 10, 25, and 50 mV/s, utilizing a three-electrode configuration (Fig. 6a). As depicted in Fig. 6a, increasing the scan rate resulted in a corresponding rise in current. This behavior may be rooted in the fact that PANI in the composition causes growth on the electrode surface, thereby increasing the current and electrochemical performance60. The CV curves for all shapes exhibit a pair of symmetric redox peaks, which correspond to pseudocapacitance behavior.

Additionally, as the scan rate increases, the oxidation peak migrates to a higher potential while the reduction peak shifts to a lower potential, mainly due to the resistance of the electrode. This suggests that the improved electrochemical performance is a result of the synergistic effects of the components within the synthesized nanocomposite. EIS was utilized to investigate further the supercapacitive properties, electrolyte movement, and resistance at the electrolyte-electrode interface. The Nyquist plot of the EIS spectrum of the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 sample with a fitted equivalent circuit in the frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 mHz with a bias potential of 5 mV is presented in Fig. 6b. Typically, the EIS profile consists of an inclined line in the low-frequency domain, indicating the Warburg diffusion process, which shows the ion infiltration from the solution into the bulk of the active electrode material.

Additionally, a quasi-semicircle appears in the high-frequency domain, representing the charge transfer resistance (RCT)61. The point where the curve intersects the real axis at high frequencies corresponds to the solution resistance (RS), encompassing the series resistance that includes the electrode’s inherent resistance, the electrolyte’s internal resistance, and the semicircle’s diameter observed at elevated frequencies. The distance in contact with the current collector (RS) from the origin of the actual impedance axis to the formed semicircle represents the resistance62. The elements of the circuit were composed of solution resistance (RS), a charge transfer resistance (RCT), constant phase element (CPE) of pseudocapacitance, and the Warburg resistance (ZW). The results of these resistances are given in Table 3.

A GCD test was performed to provide a more detailed demonstration of the electrochemical performance of the prepared product. Figure 7a exhibits charge-discharge curves of the PANI- MOF5@MS-NH2 electrode in 1 M H2SO4 in the potential window of − 0.2 to 0.8 V/s at the current densities of 1, 3, 5, and 10 A/g. The electrode exhibits nonlinear behavior in the GCD curves, suggesting that its supercapacitive performance results from a combination of the electrical double layer and pseudocapacitive effects63. The curve behavior indicates a supercapacitive property and excellent reversibility, and the results completely match those of the CV curves. In addition, the stability of the peaks at high current densities is related to the material’s electrochemical performance and fast kinetics. The nanocomposite electrode’s specific capacitance value was 757 F/g at the current density of 1 A/g. Moreover, the electrochemical measurements were conducted using 1 M KOH and 1 M Na2SO4 electrolytes, in addition to the previously studied 1 M H2SO4. The galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) curves of the electrode material at a current density of 1 A/g in all three electrolytes were plotted side-by-side for a direct comparison (Fig. S1).

Based on the GCD results and the calculated specific capacitance values using Eq. (1) the sample exhibited a significantly higher specific capacitance in 1 M H2SO4 than in the neutral (Na2SO4) and alkaline (KOH) electrolytes. This enhanced performance in the acidic medium may be attributed to the improved ionic conductivity and higher availability of H+ ions, which facilitate faster charge transfer and stronger pseudocapacitive interactions, particularly with polyaniline-based systems. These findings justify our choice of 1 M H2SO4 as the optimal electrolyte for this study.

Furthermore, as summarized in Table 4, the privileges of applying the prepared PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite as the electrode in the electrochemical system are compared with other reported similar electrode materials. Evidently, the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 electrode has demonstrated better supercapacitive performance, suggesting significant potential for its application in supercapacitors. Figure 7b shows the relation between specific capacitance values and current densities. It is evident that when the current intensifies, the specific capacitance diminishes. This reduction in capacitance at elevated currents is due to the limited movement of ions from the electrolyte solution to the electrode. Cyclic stability is an important factor in energy storage applications, which shows how much initial capacitance it maintains when a device is charged/discharged in successive cycles. The electrode’s cyclic stability was tested under a current density of 5 A/g. Figure 7c reveals that the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 electrode retains 98.8% of its initial capacitance after 8000 GCD cycles, demonstrating remarkable electrochemical stability and reversibility of the PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 electrode material. In order to evaluate the long-term electrochemical stability, the charge–discharge profiles were recorded at every 1000th cycle up to 8000 cycles. As presented in Fig. 7c, the GCD curves show only a 1.2% decrease in discharge time from cycle 1 to 8000, indicating the excellent cyclic stability of the electrode. As an ideal situation would have 100% coulombic efficiency, in Fig. 7d, PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite displays a 128% coulombic efficiency due possibly due to pseudocapacitive contributions and experimental conditions. Following this, the performance of energy storage was illustrated using a Ragone chart, where the energy density (E in Wh/kg) is mapped in relation to the power density (P in W/kg). According to the Ragone plot presented in Fig. 7e, the highest value of E (27 Wh/kg) was achieved at the current density of 1 A/g with a P value of 128 W/kg.

Conclusion

The PANI-MOF5@MS-NH2 nanocomposite was successfully synthesized and evaluated as a supercapacitor electrode in this study. Synthesized nanocomposite shows high electrical conductivity, a large surface area, more electrochemically active sites, and improved wetting properties in the electrolyte-electrode interface. CV revealed clear pseudocapacitive behavior with increasing current at higher scan rates, indicating efficient charge storage. EIS demonstrated low solution and charge transfer resistances, confirming effective ion and electron transport. GCD tests showed a high specific capacitance of 757 F/g at 1 A/g and outstanding cyclic stability, retaining 98.8% of initial capacitance after 8000 cycles. The electrode also exhibited a coulombic efficiency of 100%, likely due to pseudocapacitive contributions and experimental conditions. Moreover, an energy density of 27 Wh/kg and power density of 128 W/kg were achieved, surpassing many comparable materials. These results highlight the synergistic effects within the nanocomposite, confirming its potential as a promising material for high-performance supercapacitor applications.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dhineshkumar, S., Rajkumar, S., Sathiyan, A. & Merlin, J. P. Fabrication of Ag2WO4/PANI composite with enhanced supercapacitor performance. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 35, 1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-024-13202-2 (2024).

Aarthi, J. et al. Facile synthesis of Ce2(WO4)3-decorated polyaniline composites as promising electrode material for supercapacitor applications. Ionics (Kiel). 30, 5723–5735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-024-05676-1 (2024).

Shahmohammadi, A. et al. Transition metal phosphide/molybdenum disulfide heterostructures towards advanced electrochemical energy storage: Recent progress and challenges. RSC Adv. 15, 13397–13430. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5RA01184A (2025).

Omidvar, M. et al. Fabrication of an efficient supercapacitor based on defective mesoporous carbon as electrode material utilizing reactive blue 15 as novel redox mediator for natural aqueous electrolyte. Fuel 347, 128472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128472 (2023).

Dalvand, S. et al. A review on carbon material-metal oxide-conducting polymer and ionic liquid as electrode materials for energy storage in supercapacitors. Ionics (Kiel). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-024-05426-3 (2024).

Jouybar, S., Naji, L., Mozaffari, S. A. & Tafreshi, S. In situ electrochemical cobalt doping in perovskite-Structured lanthanum nickelate thin film toward energy conversion enhancement of polymer solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c04669 (2024).

Mehmood, T. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnBi2O4/PANI nanocomposite: A high-performance electrode material for next-generation supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 1031, 180887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2025.180887 (2025).

Dhineshkumar, S., Rajkumar, S. & Merlin, J. P. Development of high performance CoWO4@g-C3N4 composite as an electrode material for asymmetric supercapacitor application. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2025.04.051 (2025).

Kumar, N., Kim, S. B., Lee, S. Y. & Park, S. J. Recent advanced supercapacitor: A review of storage mechanisms, electrode materials, modification, and perspectives. Nanomaterials 12, 3708. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12203708 (2022).

Jouybar, S., Naji, L., Mozaffari, S. A., Sarabadani Tafreshi, S. & de Leeuw, N. H. Electrochemically engineered lanthanum nickelate as a promising transparent hole-transport layer for bulk heterojunction polymer solar cells: An experimental and DFT study. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 7, 1647–1665. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.3c03274 (2024).

Jamshidi, E., Dalvand, S., Manteghi, F. & Mousavi-Khoshdel, S. M. A cobalt-aluminium layered double hydroxide with a nickel core-shell structure nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. IScience. 28, 111672. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.111672

Forouzandeh, P., Kumaravel, V. & Pillai, S. C. Electrode materials for supercapacitors: A review of recent advances. Catalysts 10, 969 https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10090969 (2020).

Dalvand, S., Yaghoubi, S., Morteza Mousavi-Khoshdel, S. & Ghafuri, H. Investigating the application of caffeine-based ionic liquid modified by zinc bromide as an effective electrode in supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage. 44, 103323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.103323 (2021).

Reenu, Sonia, L., Phor, A., Kumar, S. & Chahal Electrode materials for supercapacitors: A comprehensive review of advancements and performance. J. Energy Storage. 84, 110698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.110698 (2024).

Askari, M. B., Salarizadeh, P., Moghadam, M. T. T., Azizi, S. & Ramezan Zadeh, M. H. Binary transition metal oxide/carbon compounds-based electrode materials for supercapacitor application: A comprehensive review. J. Alloys Compd. 1027, 180573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2025.180573 (2025).

Dashtian, K. et al. Recent trends in molecularly imprinted photoelectrochemical sensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 189, 118271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2025.118271 (2025).

Foroozandeh, A. et al. Recent advancements in biosensors for diagnosis of ovarian cancer: Analytical approaches. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 183, 118119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2024.118119 (2025).

Qu, Y., Shi, C., Cao, H. & Wang, Y. Synthesis of Ni-MOF/Ti3C2Tx hybrid nanosheets via ultrasonific method for supercapacitor electrodes. Mater. Lett. 280, 128526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2020.128526 (2020).

Kishore babu, S., Jayachandran, M., Maiyalagan, T., Vijayakumar, T. & Gunasekaran, B. Metal-organic framework (MOF-5) incorporated on NiCo2O4 as electrode material for supercapacitor application. Mater. Lett. 302, 130338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130338 (2021).

Hassan, H. et al. Innovative MOF-5/V2CTx composite for high-performance, and ultra-fast supercapacitors and hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta. 489, 144277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2024.144277 (2024).

Argirusis, C., Katsanou, M. E., Alizadeh, N., Argirusis, N. & Sourkouni, G. Recent advances in the application of MOFs in supercapacitors. Batteries 11, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11050181 (2025).

Shanmugam, S. et al. N, P and N, S dual doped carbon replicas of SBA-15 template for high performance symmetric supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage. 85, 111087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.111087 (2024).

Ponghiransmith, C., Lin, J. Y., Kobsiriphat, W., Limthongkul, P. & Hasin, P. High-performance asymmetric supercapacitor achieved by CoS2 nanoparticles decorated polyaniline functionalized SBA-15-derived mesoporous nitrogen-doped carbon with rod-like architectures. J. Alloys Compd. 898, 162773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.162773 (2022).

Subramani, K. et al. Dual heteroatoms doped SBA-15 templated porous carbon for symmetric supercapacitor in dual redox additive electrolyte. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08.002 (2022).

Hashemikia, S., Hemmatinejad, N., Ahmadi, E. & Montazer, M. A novel cotton fabric with anti-bacterial and drug delivery properties using SBA-15-NH2/polysiloxane hybrid containing tetracycline. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 59, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2015.09.092 (2016).

Hashami, Z., Taheri, A. & Alikarami, M. Synthesis of a magnetic SBA-15-NH2@Dual-Template imprinted polymer for solid phase extraction and determination of Pb and cd in vegetables; Box Behnken design. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1204, 339262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2021.339262 (2022).

Rajkumar, S., Christy Ezhilarasi, J., Saranya, P., Princy, J. & Merlin Fabrication of CoWO4/PANI composite as electrode material for energy storage applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 162, 110500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110500 (2022).

Srinivasan, R., Elaiyappillai, E., Anandaraj, S., kumar Duvaragan, B. & Johnson, P. M. Study on the electrochemical behavior of BiVO4/PANI composite as a high performance supercapacitor material with excellent cyclic stability. J. Electroanal. Chem. 861, 113972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.113972 (2020).

Rajkumar, S., Gowri, S., Dhineshkumar, S., Merlin, J. P. & Sathiyan, A. Investigation on NiWO4/PANI composite as an electrode material for energy storage devices. New. J. Chem. 45, 20612–20623. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NJ03831A (2021).

Rajkumar, S., Elanthamilan, E., Princy Merlin, J. & Sathiyan, A. Enhanced electrochemical behaviour of FeCo2O4/PANI electrode material for supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 874, 159876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.159876 (2021).

Rajkumar, S., Elanthamilan, E., Merlin, J. P., Daisy Priscillal, I. J. & Lydia, I. S. Fabrication of a CuCo2O4/PANI nanocomposite as an advanced electrode for high performance supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 4, 5313–5326. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0SE00913J (2020).

Rajasekaran, S. et al. Sm-MOF/rGO/PANI composite as an electrode material for supercapacitor applications. Electrochim. Acta. 467, 143031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2023.143031 (2023).

Gopi, R. et al. Synthesis and investigation of charge storage characteristics in Ni-MOF/PANI composite as an active electrode material for supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta. 507, 145130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2024.145130 (2024).

Le, Q. B. et al. Electrochemical performance of composite electrodes based on rGO, Mn/Cu metal–organic frameworks, and PANI. Sci. Rep. 12, 664. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04409-y (2022).

Qin, D., Zhou, B., Li, Z. & Yang, C. Construction of controllable multicomponent ZnO–ZnCo/MOF-PANI composites for supercapacitor applications. J. Mol. Struct. 1309, 138140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138140 (2024).

Sun, P. P., Zhang, Y. H., Shi, H. & Shi, F. N. Controllable one step electrochemical synthesis of PANI encapsulating 3d-4f bimetal MOFs heterostructures as electrode materials for high-performance supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 130836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130836 (2022).

Gharajedaghi, S. et al. Ethylene trimerization using half-sandwich titanium‐based catalysts supported on mesoporous silica modified with ionic liquids. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 38, e7431. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.7431 (2024).

Ahmadi, E. et al. Phillips catalysts synthesized over various silica supports: characterization and their catalytic evaluation in ethylene polymerization. Polyolefins J. https://doi.org/10.22063/poj.2016.1268 (2016).

Ghasemnejad, M., Ahmadi, E., Mohamadnia, Z., Doustgani, A. & Hashemikia, S. Functionalized silica nanoparticles as a carrier for betamethasone sodium phosphate: Drug release study and statistical optimization of drug loading by response surface method. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 56, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2015.06.012 (2015).

Ahmadi, E., Mohamadnia, Z., Mashhadi-Malekzadeh, A., Hamdi, Z. & Saghatchi, F. Preparation, characterization, and polymerization of chromium complexes‐grafted Al/SBA‐15 and Ti/SBA‐15 nanosupports. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 128, 4245–4252. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38353 (2013).

Ahmadi, E., Haghighi, M. N., Mohamadnia, Z. & Ramazani, A. Preparation of shish-kebab and nanofiber polyethylene with chromium/Santa Barbara amorphous silica‐15 catalysts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 118, 3658–3665. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.32583 (2010).

Mohamadnia, Z., Ahmadi, E., Nekoomanesh, M., Ramazani, A. & Mobarakeh, H. S. Effect of support structure on the activity of Cr/nanosilica catalysts and the morphology of prepared polyethylene. Polym. Int. 59, 945–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.2811 (2010).

Wang, C., Shang, F., Yu, X., Guan, J. & Kan, Q. Synthesis of bifunctional catalysts Al-SBA-15-NH2 with high aluminum content and the catalytic application for different one-pot reactions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 6846–6852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.03.117 (2012).

Dalvand, S., Omidvar, M., Asghari, A., Mohammadi, N. & Yazdanfar, N. Designing and fabricating high-performance supercapacitor based on defective mesoporous carbon as electrode and disperse blue 6 as novel redox additive electrolyte. J. Porous Mater. 30, 2069–2078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10934-023-01483-7 (2023).

Zheng, L., Yang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhu, T. & Wang, X. Functionalization of SBA-15 mesoporous silica with bis-schiff base for the selective removal of Pb(II) from water. J. Solid State Chem. 301, 122320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2021.122320 (2021).

Liou, T. H., Chen, G. W. & Yang, S. Preparation of amino-functionalized mesoporous SBA-15 nanoparticles and the improved adsorption of Tannic acid in wastewater. Nanomaterials 12, 791 https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12050791 (2022).

Bouider, B. et al. MOF-5/Graphene oxide composite photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic activity of methylene blue degradation under solar light. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 33, 4001–4011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-023-02668-y (2023).

Foroozandeh, A., Pourmadadi, M., SalarAmoli, H. & Abdouss, M. Aptamer-enabled electrochemical bioplatform utilizing surface-modified g-C3N4/MoS2/PANI nanocomposite for detection of CA125 biomarker, Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 45, 100669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbsr.2024.100669 (2024).

Foroozandeh, A., Abdouss, M., SalarAmoli, H., Pourmadadi, M. & Yazdian, F. An electrochemical aptasensor based on g-C3N4/Fe3O4/PANI nanocomposite applying cancer antigen_125 biomarkers detection. Process. Biochem. 127, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2023.02.004 (2023).

Shahriarinour, M., Divsar, F. & Nazari Shad, Z. Grape seed extract loaded amino functionalized SBA-15 mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system: Antibacterial activity and release kinetics studies. Biotechnol. J. Environ. Microbiol. 1, 142–154. https://doi.org/10.30495/bioem.2022.705272 (2022).

Liu, H., Ding, W., Lei, S., Tian, X. & Zhou, F. Selective adsorption of CH4/N2 on Ni-based MOF/SBA-15 composite materials. Nanomater (Basel Switzerland) 9, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9020149 (2019).

Shen, J. et al. Synthesis of magnetic short-channel mesoporous silica SBA-15 modified with a polypyrrole/polyaniline copolymer for the removal of mercury ions from aqueous solution. ACS Omega. 6, 25791–25806. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c04249 (2021).

Hu, Z. et al. High specific capacitance of polyaniline/mesoporous manganese dioxide composite using KI-H2SO4 electrolyte. Polym. (Basel). 7, 1939–1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym7101491 (2015).

Foroozandeh, A., SalarAmoli, H., Abdouss, M. & Pourmadadi, M. Development of a labeled-free and labeled electrochemical aptasensor for the detection of cancer antigen 125 by using magnetic g-C3N4/MoS2 nanocomposite. Sens. Actuat. Rep. 7, 100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snr.2024.100195 (2024).

Xu, Y., Wang, C., Zhou, G., Wu, Y. & Chen, J. Improving the controlled release of water-insoluble emodin from amino-functionalized mesoporous silica. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 6366–6372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.03.041 (2012).

Lv, D. et al. Efficient mechanochemical synthesis of MOF-5 for linear alkanes adsorption. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 62, 2030–2036. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jced.7b00049 (2017).

Aghajani, K. & Tayebi, H. A. Synthesis of SBA-15/PAni mesoporous composite for adsorption of reactive dye from aqueous media: RBF and MLP networks predicting models. Fibers Polym. 18, 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-017-6610-4 (2017).

Yang, H., Li, J., Zhang, H., Lv, Y. & Gao, S. Facile synthesis of POM@MOF embedded in SBA-15 as a steady catalyst for the hydroxylation of benzene. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 195, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.04.023 (2014).

khorshidi, M., Asadpour, S., Sarmast, N., Aramesh-Boroujeni, Z. & Sadegh, N. Enhanced adsorption performance of tetracycline in aqueous solutions using Mg-Al-LDH/AC nanocomposite. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 105301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105301 (2023).

Hamedani, H., Ghasemi, A. K., Kafshgari, M. S., Zolfaghari, Y. & Kafshgari, L. A. Electrochemical performance of 3D porous PANI/Gr/MIL-100(Fe) nanocomposite as a novel smart supercapacitor electrode material. Synth. Met. 298, 117428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2023.117428 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Kinetics-favorable heterojunctional CNTs@CuCo-LDH/BPQD electrode with boosted charge storage capability for supercapacitor. Appl. Surf. Sci. 609, 155287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155287 (2023).

Vanaraj, R., Daniel, S., Haldhar, R., Asrafali, S. P. & Kim, S. C. Direct growth of TiO2–MoO2/MnO2–MoO2 on plasma-treated carbon-cloth surface for high-performance supercapacitor and oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta. 440, 141705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2022.141705 (2023).

Talluri, B., Aparna, M. L., Sreenivasulu, N., Bhattacharya, S. S. & Thomas, T. High entropy spinel metal oxide (CoCrFeMnNi)3O4 nanoparticles as a high-performance supercapacitor electrode material. J. Energy Storage. 42, 103004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.103004 (2021).

Quoc Bao, L. et al. Electrochemical performance of composites made of rGO with Zn-MOF and PANI as electrodes for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta. 367, 137563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2020.137563 (2021).

Zhu, C. et al. ZnO@MOF@PANI core-shell nanoarrays on carbon cloth for high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. J. Energy Chem. 35, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2018.11.006 (2019).

Iqbal, M. Z., Faisal, M. M., Ali, S. R., Farid, S. & Afzal, A. M. Co-MOF/polyaniline-based electrode material for high performance supercapattery devices. Electrochim. Acta. 346, 136039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136039 (2020).

Zhang, X., Li, D., Dong, C., Shi, J. & Xu, Y. The synergistic supercapacitive performance of Mo-MOF/PANI and its electrochemical impedance spectroscopy investigation. Mater. Today Commun. 21, 100711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2019.100711 (2019).

Khuyen, N. Q., Kiefer, R. & Le, Q. B. rGO/Ni-MOF composite modified with PANI applied as electrode materials for supercapacitor. Chem. Lett. 52, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.220436 (2023).

Han, J. J., Yan, Q., Chen, Z., Wang, Z. & Chen, C. Application of Cr-metal organic framework (MOF) modified polyaniline/graphene oxide materials in supercapacitors. Ionics (Kiel). 28, 2349–2362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-022-04443-4 (2022).

Srinivasan, R., Elaiyappillai, E., Nixon, E. J., Sharmila Lydia, I. & Johnson, P. M. Enhanced electrochemical behaviour of Co-MOF/PANI composite electrode for supercapacitors. Inorganica Chim. Acta. 502, 119393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2019.119393 (2020).

Shao, L. et al. A high-capacitance flexible solid-state supercapacitor based on polyaniline and metal-organic framework (UiO-66) composites. J. Power Sources. 379, 350–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.01.028 (2018).

Marwat, M. A. et al. Enhancing supercapacitor performance of Ni–Co–Mn metal–organic frameworks by compositing it with polyaniline and reduced graphene oxide. RSC Adv. 14, 2102–2115 (2024).

Savić, M. et al. Carbonization of MOF-5/polyaniline composites to N,O-doped carbon/ZnO/ZnS and N,O-doped carbon/ZnO composites with high specific capacitance, specific surface area and electrical conductivity. Mater. (Basel). 16, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031018 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions statement Alireza Alizadeh carried out the experiments, prepared the supercapacitor, and provided all characterizations. Alireza Alizadeh and Ebrahim Ahmadi analyzed and interpreted the data, discussed the results and contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript. Ebrahim Ahmadi conceived and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alizadeh, A., Ahmadi, E. Polyaniline and MOF5 functionalized mesoporous silica composite as electrode for high performance symmetric supercapacitor. Sci Rep 15, 40233 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24044-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24044-1