Abstract

The surface roughness of precast elements significantly impacts the shear performance of the bonding surface (BS). To enhance roughness while minimizing environmental impact, this study introduces a frustum multikey block rough surface created via a mold. To assess the shear performance of this key block BS, push-off tests were conducted on 48 specimens. The study focused on key factors such as the types of BS, key block sizes, defect rates, confining stress levels, and concrete strength classes. The results revealed that the key block BS exhibited the highest shear capacity (Vu) among all BS types. Vu increased with increasing key block size and confining stress and concrete strength but decreased as the defect rate increased. Additionally, finite element simulations and prediction formulas for Vu were developed, and the results closely aligned with the test data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assembled monolithic concrete structures (AMCSs) combine precast and cast-in-place elements, making them a popular choice for high-rise and ultrahigh-rise buildings in densely populated areas of China1,2. In AMCSs, precast elements are connected via reinforcement and cast-in-place concrete, resulting in numerous bonding surfaces (BSs) at the joints. These BSs are essential for transferring compressive and shear stresses within the structure. However, they also introduce discontinuities that are more prone to damage than the surrounding concrete, potentially compromising structural safet 3. Therefore, careful design of BSs is vital to ensure the overall integrity and performance of the structure.

Although the presence of BS introduces structural discontinuities, a reliable interface roughening treatment can enhance shear performance, preventing BS failure under excessive stress and ensuring structural safety. Conventional treatments such as sandblasting, chipping with jackhammers (CJs), water jets (W), and as-cast-by-patterned steel plates (PSPs) are widely used for interface treatment4. Typically, interfaces subjected to different treatments have different roughness, which results in inconsistent bond strengths between the interfaces. The use of CJ can cause damage to precast elements under impact, resulting in microcracks and thus a weak BS5. Among the currently used methods, the W method is likely the best type of treatment for interface roughness6. This is because this approach not only results in a high roughness of the treated interface but also has high efficiency when treating large areas. The wastewater produced by the W method contains a large amount of retarder, which can lead to environmental pollution if not properly treated. Sandblasting is also considered to be an efficient treatment, but Talbot et al.7 noted that this produces a polishing effect, which leads to poor bond strength between the interfaces. The depth of the groove on the surface of the steel plate in the PSP method is usually set very shallow for easy demolding. However, this also leads to poor interfacial bond strength. In China, the PSP method is often combined with the W method, which is widely used in the interface treatment of precast concrete shear walls. There is a lack of research on the bond strength between the interfaces formed by the PSP and W methods. Notably, the same treatment may also result in different. For example, operator skill, time of operation and age of the concrete affect roughness. Among them, the influence of human factors on the interface roughness is uncontrollable and may lead to a low bond strength between the interfaces. On the basis of safety considerations, the size of the roughness at the interface of precast concrete elements is specified in JGJ1-20148. Notably, conventional rough surfaces have random interface geometries, which can waste much labor and time when performing roughness inspections. In conclusion, traditional rough surface treatment methods are heavily influenced by human factors, often resulting in irregularly shaped rough surfaces that compromise the strength and ductility of the joint. Furthermore, the need for secondary treatment introduces added complexity, reduces construction efficiency, and increases labor costs. These methods also contribute to water wastage and dust pollution, creating environmental burdens. As a result, there is a clear need for an alternative treatment process that is cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and capable of producing uniformly controlled roughness.

The shear transfer between BSs was first described on the basis of the shear friction theory proposed by Birkeland9. The theory mainly assumes that the interface shear force is provided by friction. To this end, scholars have added the contribution of cohesion and the role of dowel action in internal connection reinforcement10. The cohesion consists of both bonding and aggregate occlusion. For unconnected reinforcement BS (URBS), the shear performance is related mainly to cohesion and friction. The URBS exhibited typical brittle damage due to the absence of dowel action of the connecting reinforcement. The cohesive bonding action originates from physical and chemical bonding, and aggregate occlusion can be improved by roughness treatment11,12. The magnitude of cohesion is also influenced by factors such as concrete strength and stiffness, curing conditions, aggregates, and age. Santos and Júlio13 reported that the bond strength of specimens under laboratory curing conditions was greater than that under outdoor curing conditions. Moreover, the older the concrete layers, the stronger the interfacial bond strength. Li et al.14 reported that the bond strength is related to the particle size of the interfacial aggregate, and the optimum aggregate size was 20 mm. Increasing the strength class of the concrete between the interfaces improves the bond strength of the interfaces15,16,17. The application of lightweight aggregate concrete and recycled aggregate concrete negatively affects the interface shear strength18. The crushing and fragmentation of aggregates reduce the contribution of interfacial aggregate occlusion to the shear strength. Xiao et al.19 suggested that the replacement of recycled aggregate should not exceed 30%. The friction of BS is related to the externally applied pressure in addition to the roughness. The shear friction characteristics and limits between the initially uncracked and initially cracked interfaces were derived by Haskett et al.20. Compared with static loading, the shear strength between interfaces decreases significantly under dynamic cyclic loading. Moreover, the friction coefficient and effective damping decrease with increasing loading rate21. The shear strength between BS is also influenced by the roughness size, shape, and spatial distribution of the interface22,23. Choi et al.24 pointed out that the shear strength of interfaces without keys is 65.3% lower than those with keys. To improve bearing capacity, Zhang et al.25 recommended that the key angle be less than 45°. Kwon et al.26, based on direct shear tests, demonstrated that joints with different roughness sizes fail progressively in the order of roughness size, and significant variations in the same interface roughness size lead to a substantial reduction in strength and ductility. Feng et al.27 highlighted that changes in joint geometry affect the shear behavior, with an increase in joint width causing rotational effects that weaken joint performance. Yuan et al.28 noted that the shear strength of the interface improves with increased key depth and decreased key spacing.

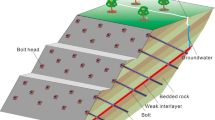

To address the limitations of traditional forming methods, this study proposes a more economical and environmentally friendly approach that meets practical engineering requirements while achieving a uniform roughness distribution. The method employs a processing technique known as the multi-key block rough surface (as shown in Fig. 1). Specifically, a prefabricated rough surface mold is securely installed within the formwork of the precast concrete component, enabling the concrete to form a rough surface that is a mirror image of the mold after curing.

Building on existing research regarding the influence of roughness shape, angle, and spacing on interface shear capacity (Vu), the mold in this study is designed with uniformly distributed frustum-shaped key blocks and micro-protrusions29. To maximize the shear resistance of these key blocks, their dimensions have been optimized to accommodate the maximum coarse aggregate particle sizes specified by ASTM C3330 and GB/T 14,684 − 201131 (5 ~ 25 mm and 5 ~ 31.5 mm, respectively). In particular, the incircle diameter at the base of the key blocks is set to 32 mm, ensuring that aggregates within the specified size range can completely fill the spaces between the key blocks. This design is expected to enhance the aggregate interlock effect at the joint, thereby improving the Vu32.

As mentioned earlier, extensive research has been conducted on shear transfer and the shear performance of interfaces. However, most of these studies have focused on interfaces treated with conventional methods, which typically result in irregular roughness. Research on the shear performance of prefabricated interfaces with uniform roughness is limited, especially regarding how different roughness shapes and sizes affect interface performance. Consequently, further investigation into the shear performance of the multi-keyed interface proposed in this study is necessary to clarify its performance differences compared to traditional interfaces.

Currently, the push-off test using Z-shaped specimens is widely employed to evaluate interface shear performance33. Accordingly, this study designed 48 Z-shaped URBS (Uniform Roughness Bond Surface) specimens, which were tested under static push-off loading. The effects of interface type, key block size, confining pressure level, and concrete strength on shear performance were comparatively analyzed. Based on the experimental results, a formula for calculating the Vu of URBS was derived. Additionally, a finite element model was developed to accurately simulate the shear behavior between the interfaces.

Research significance

This study introduces a novel multi-key block rough surface technology for precast concrete components, with clear engineering significance. By securely embedding reusable molds in the formwork, the rough surface is formed directly during curing as a mirror image of the mold34,35, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Compared with traditional methods, this approach simplifies construction operations, reduces labor costs, and improves efficiency. The use of recyclable molds also mitigates water waste and dust pollution, offering notable environmental benefits. Furthermore, by eliminating impact-based surface treatments, the risk of interface microcracks is reduced, thereby enhancing structural safety and durability. Overall, this technology provides both methodological innovation and practical value for precast interface evaluation in engineering practice.

Test program

Test variables and test specimens

This study focused on key variables such as the bond surface (BS) type, confining stress level, frustum size, and concrete strength. The BS types evaluated included mold key blocks (M), triangle grooves (T), chipping with jackhammers (CJ), water jets (W), and as-cast by patterned steel plate (PSP) forms. Additionally, a monolithic cast specimen was created for comparison with the BS specimens. In the M-type BS, the key blocks consist of aggregate and mortar. Considering the particle size of commonly used aggregates in engineering and to clarify the impact of different key block dimensions, the specifications of the key blocks were determined. The key blocks are available in three specifications, with internal circle diameters of 14 mm, 24 mm, and 32 mm at the base, and are labeled Mold 1 (M1), Mold 2 (M2), and Mold 3 (M3), respectively. To assess potential damage, the BS of M2 was deliberately modified by chiseling one-third of a single key block diagonally, creating a defective key block. This study evaluates the effect of key block defect rates on interface shear performance based solely on macroscopic patterns. A defect rate of 50% was used as the baseline, with one parameter selected for comparison both below and above this threshold. Ultimately, the key block defect rates were categorized into three groups: 20, 50, and 70%.

Five levels of confining stress—0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 MPa—were applied to the BS. Three concrete strength classes, C30, C40, and C50, were selected, resulting in the fabrication of 48 specimens. In this study, the concrete strength classes C30, C40, and C50 follow the Chinese standard GB 50,010 − 2010 [36], where “C” denotes the cube compressive strength (30, 40, and 50 MPa, respectively). For reference, these approximately correspond to cylinder strengths of 24, 32, and 40 MPa in international standards. To ensure the experimental results have broad applicability and reference value, the selected concrete strength grades are based on commonly used standards in practical engineering. No innovations were made in material properties. The average concrete strength of the substrate and overlay layers was used as the BS strength. In some cases, the measured concrete strength did not match the design values, leading to the inclusion of additional strength classes, C20 and C60. This study examined the effect of the concrete strength on the shear performance on the basis of the measured BS strength. The specimen parameters are detailed in Table 1. To conserve space in the article, the characteristic load and displacement data from Chap. 3 have been consolidated into Table 1. The rough surfaces from different treatments are illustrated in Fig. 3, and the detailed dimensions of the key block molds are shown in Fig. 4.

Z-shaped specimens were used for push-off tests. The geometry of the shear specimen was 700 × 390 × 200 mm, and the BS was located in the middle of the specimen and measured 200 × 320 mm. No connecting reinforcement was provided at the BS. The detailed dimensions of the specimens are shown in Fig. 5.

Test setup and instrumentation

Z-shaped specimens were tested under monotonically increasing loads. Two 150 × 200 × 10 mm loading plates were arranged at the center of the top and bottom of the specimen. A vertical static load was applied at the loading point via a hydraulic jack and a steel plate. A vertical static load was applied at the loading point via a hydraulic jack and a steel plate. The center of the steel plate, the BS and the loading point were located in the same plane perpendicular to the ground. For specimens without confining stress, a force-controlled loading procedure was adopted, in which the load was increased in increments of 10 kN until failure occurred. The relative displacement of the bonded interface was monitored in real time throughout the loading process. For specimens with confining stress, force-controlled loading was applied before reaching the peak load, also in 10 kN increments. After the peak load was reached, the loading mode was switched to displacement-controlled loading with increments of 2 mm. The test was terminated when the relative displacement of the bonded interface reached 30 mm.

A custom-designed lateral loading device was used to apply confining stress to the specimens. The device consisted of two steel plates positioned on both sides of the specimen, connected by four threaded rods and bolts. Each bolt was connected in series with a load cell, enabling real-time measurement of the applied force. The target confining stress was achieved by gradually tightening each bolt using a torque wrench until the desired force, calculated based on the required lateral pressure and specimen dimensions, was reached and equally distributed among the four bolts. A group of disc springs with lower stiffness was installed to accommodate the relative horizontal displacement after interface failure, thereby maintaining approximately constant confining stress during the test. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) plates were placed between the steel plates and the concrete surfaces to minimize friction and ensure the accuracy of confining stress application. The test setup for both unconfined and confined specimens is shown in Fig. 6.

Two linear variable displacement transducers (LVDTs) were arranged at the upper and lower ends of the backside of the specimen and at the top surface of the specimen to monitor the vertical relative displacement of the BS. One LVDT was set at the front or back of the specimen to monitor the horizontal relative displacement of the BS. In addition, the displacements and strains on the specimen surfaces were measured via digital image correlation (DIC) for some of the specimens. The acquisition equipment and LVDT arrangement are shown in Fig. 7.

Test setup. (a) Schematic diagram of the tested specimen, (The image was generated using SketchUp, version 2018, https://www.sketchup.com/), (b) Photograph of the tested specimen.

LVDT arrangement and DIC measurement equipment. (a) LVDT arrangement, (The image was generated using SketchUp, version 2018, https://www.sketchup.com/), (b) DIC measurement equipment.

Material properties

The specimen substrate and overlay concrete were poured at 7-day intervals. Roughening of the substrate for the W and CJ specimens during the intervals between pours. The concrete cubic compressive strength fcu was determined from 11 batches of cubic samples with side lengths of 150 mm. The average axial compressive strength (fc) was evaluated by assuming that fc = 0.76 fcu36. In accordance with GB/T 228.1–202137, tensile tests were conducted for different diameters of reinforcements to obtain the yield strength, ultimate strength and elongation at break of the reinforcements. The results of the concrete material property tests of the substrate and overlay after 28 days are shown in Table 2. The mechanical properties of the reinforcement are shown in Table 3.

Test results and discussion

Failure mode

Crack distribution

All specimens exhibited distinct brittle failure characteristics. Since this study focused on shear tests of the BS, the failure processes were generally consistent across different conditions. This section primarily describes the failure process of a representative specimen, supplemented by specific cases under varying conditions. The final failure patterns of specimens with different interface types are presented in Fig. 8, while the main experimental results for each specimen are summarized in Table 1.

For the specimens subjected to confining stress, slight cracking might have occurred on the ends of the surfaces before any cracks appeared in the BS. These cracks did not propagate further after the BS cracked, and the crack widths remained under 0.2 mm by the end of the test. The presence of these cracks is related to the ultimate strength of the BS. When the BS strength is low, the first shear-induced crack quickly develops along the BS interface, leading to specimen failure. Conversely, when the BS strength is high, localized compression cracks and tensile cracks may form at the ends before the shear force reaches the failure strength. The dense cracking at the ends of the monolithic cast specimen (MC-B-50) supports this observation.

To focus on the shear performance of the BS, this section primarily describes the damage phenomena observed at the BS. Generally, the first crack observed was the main crack that penetrated the BS, indicating the complete separation of the substrate from the overlay. The formation of this main crack indicated that the specimen had reached its ultimate load (Vexp), which was often accompanied by a loud sound. The load at which the BS first cracks is termed the cracking load (Vcr). For most specimens, Vcr was equal to Vexp, although in some cases, particularly those subjected to confining stress, Vcr was slightly less than Vexp. The width of the first crack in these specimens was typically approximately 0.02 mm, with Vcr/Vexp ratios ranging from 0.77 to 1 and Dexp/Dcr ratios ranging from 1 to 1.71. Here, Dcr and Dexp refer to the relative displacements corresponding to Vcr and Vexp, respectively. The Dexp of the bonded interface portions was generally within 1 mm, although in some of the W and M specimens, it exceeded 1 mm, reaching a maximum of 1.2 mm. Testing was concluded once the unconfined stress specimens reached their Vexp, with the highest Vexp recorded at 198 kN for specimen M3-30. For the specimens subjected to confined stress, the vertical relative displacement increased sharply, whereas the load-carrying capacity decreased rapidly after reaching Vexp. Despite this, there was still a residual load due to interfacial friction under the confining stress, as indicated by the sound of aggregate grinding between the interfaces during loading. This residual load remained fairly constant even as the relative displacement increased. Notably, the failure modes were consistent across specimens, regardless of BS type, with all the failures initiated by fractures along the BS.

In summary, the failure modes across specimens with different BS types were generally consistent. When the BS exhibited strong shear resistance, the first crack typically appeared at the end of the specimen. This phenomenon was more common in M-type and W-type BSs but was not observed in PSP BSs. This observation partly reflects the differences in shear performance among the various BS types. Regardless of the location of the initial crack, ultimate failure occurred due to the propagation of a main crack along the BS. Once the main crack formed, specimens without confining pressure completely separated at the BS, terminating the test. In contrast, specimens with confining pressure were able to sustain load until reaching a critical displacement. In these specimens, higher confining pressure led to increased cracking and damage at the ends, accompanied by more pronounced sounds from aggregate interlock friction during loading. The influence of concrete strength on failure mode was minimal, although specimens with higher concrete strength produced a more noticeable sound upon the formation of the main crack. Consequently, the failure modes of all specimens were consistent, characterized by sudden and short-duration failures, indicating typical brittle failure behavior.

Interfacial damage of BS

The roughness (Rt) of the interfaces with different treatments, measured via the sand spreading method, is presented in Table 4. Photos of the Rt measurements are shown in Fig. 9. Among all the treatments, the M3 rough surface presented the highest Rt, followed by W, M2, T, M1, CJ, and PSP. Notably, during the lifting and transportation of the specimens, interface fractures occurred in the PSP specimens, which had the lowest Rt.

The BS damage of the confined stress specimens is illustrated in Fig. 10. According to Fig. 10, all the key blocks between the interfaces of the M specimens were sheared off at the root, and a damage pattern was also observed in the unconfined stress specimens. This specific interfacial damage pattern in the M specimens was not observed for the other interface types. In the T specimens, interfacial damage was limited to the tips of the projections, with no shearing at the roots. The likely reason for this is that the long axis of the bottom surface of the projection aligns with the direction of the applied force, making it unlikely for the root to be sheared off under the applied shear force. However, this alignment does not fully utilize the load‒carrying capacity of the projections. Additionally, no significant damage was observed in the projections at the PSP interface. This is likely because the projections are small in height and offer minimal resistance to shear. Consequently, when the specimen’s Rt is low, the bond strength breakdown is more pronounced, and the contribution of aggregate interlocking is minimal.

During the loading process of the W specimen with confining stresses, a distinct grinding sound of aggregate phases could be heard after the interface fractured. According to the damage diagram of the BS for the W specimen, the aggregates at the interface were crushed against each other under vertical and horizontal loads, leading to aggregate crushing. The CJ specimens also experienced interaggregate galling and crushing at the interfaces. However, since the Rt of the CJ specimens was less than that of the W specimens, the interfacial damage was less severe. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 10, the shearing of aggregates at the interface of the monolithic cast specimen was more pronounced than that in the W specimen.

The analysis of post-failure damage at the interface indicates that the size and orientation of key blocks play a critical role in shear behavior. When the key blocks are small, their contribution to shear resistance at failure is limited. Moreover, when the long axis of the protrusion base aligns with the direction of the applied force, the root of the protrusion is less likely to be sheared off, potentially leading to underutilization of its strength. Additionally, increased roughness and higher confining pressure enhance aggregate interlock wear at the interface, thereby improving shear resistance.

Specimen surface displacement and strain

Taking the M3-B-20 specimen as an example, the strain and displacement fields on the surface of the specimen can be described as follows. As shown in Fig. 11, the displacement field on the surface is essentially symmetrically distributed. Specifically, the transverse (X) displacement on the specimen surface decreases progressively from the upper portion to the lower portion. The vertical (Y) displacement of the loaded side of the BS was greater than that of the restrained side. Owing to the bonding action of the concrete, the restrained portion experiences both lateral and vertical displacements along with the loaded portion. Consequently, the total displacement of the specimen surface decreases from the loaded portion to the restrained portion.

Figures 11d,e display the average displacement change along the stage lines during loading, as indicated in (Fig. 11a). Before the BS fractures, the restrained portion deforms in tandem with the loaded displacements. After the BS fractures, the deformation of the restrained portion decreases, although some plastic deformation remains. This means that the higher the bond strength, the greater the deformation of the restrained portion. Additionally, this deformation of the restrained portion can lead to cracking of the concrete on the side of the specimen.

Figure 12 shows the strain field just before the BS fractures. The transverse strain field clearly differs significantly from the main strain field, whereas the tangential and longitudinal strain fields closely align with the main strain field. This comparison reveals that the specimens primarily deform along the longitudinal and tangential directions. Furthermore, the principal strains decrease progressively from the BS toward the ends of the specimens, suggesting that shear forces are predominantly transmitted along the BS.

Load vs. relative displacement curve at the BS

Effect of the BS type

Unconfined stress specimens

The results of the experiment are summarized in Table 1. To eliminate the bias present in the concrete strength, the shear stress of each specimen was normalized by the compressive strength of the concrete. The normalized shear stress (τu1) is defined as \({{\tau _{u} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\tau _{u} } {\sqrt {f_{{\text{c}}} } }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\sqrt {f_{{\text{c}}} } }}\), where τu represents the shear strength at the BS and fc is the axial compressive strength of the concrete at the BS.

Figure 13 shows the τu1-relative displacement relationship for the unconfined stress specimen. After each specimen reached τu1, the BS completely lost its load-carrying capacity and exhibited brittle failure. Among the BS types, the maximum relative displacement at the point at which τu1 was reached was only 0.4 mm. The PSP specimen with the smallest BS Rt had the smallest τu1. Compared with those of PSP-30, the τu1 values of the M3-30, W-30, M2-30, CJ-30 and T-60 specimens increased by 181.8%, 159.1%, 104.5, 72.4 and 4.5%, respectively.

Confining stress specimens

Figure 14a shows the τu1-relative displacement relationship for the specimens subjected to a 1 MPa confining stress. Unlike the unconfined stress specimens, the BS in the specimens with 1 MPa confining stress began to crack before reaching τu1. This cracking at the interface indicated a reduction in bond strength. The ratio of cracking load to ultimate load Vcr/Vexp for each specimen at 1 MPa ranged from 0.81 to 1.

As vertical loading continued, the shear stress curve increased with decreasing slope until it reached τu1. Significant degradation in strength and stiffness was observed after reaching τu1, indicating complete failure of the bond strength between the interfaces. For the M specimen, key blocks were fully crushed from the root upon reaching τu1. Post-τu1, the shear stress of the confined stress specimens dropped sharply decreased, whereas the relative displacement between the BSs markedly increased. The specimens subsequently retained some residual strength due to friction. This behavior was consistent across all the confined stress specimens. The ductility index, defined as the ratio of Dexp to Dcr, ranged from 1 to 1.71 for all specimens.

Among all BS specimens, the M3 specimen had the highest τu1 value. Compared with those of the other treatments, the τu1 values of the M3 specimens increased by 3.9% to 81.4%. The W specimen had a τu1 slightly lower than that of M3, followed by the M2, T, M1, CJ, and PSP specimens, which aligns with the Rt magnitude measured at the interface in Sect. 3.1.2. Specifically, the τu1 values for the M2 and M1 specimens decreased by 16.8% and 37.4%, respectively, compared with those of the M3 specimen. This finding indicates that τu1 for the M specimens improved with increasing key block size. Conversely, for the M specimens with defect rates of 20%, 50%, and 70%, τu1 decreased by 13.5% to 18% as the defect rate increased. However, the τu1 of the 70% defect rate specimen remained higher than that of the T, M1, CJ, and PSP specimens. The post τu1 curves of the specimens reflected the friction between the BSs, with normalized residual loads for the specimens under a 1 MPa confining stress ranging from 61.5 to 78 kN.

The τu1-relative displacement relationships of the specimens under 0.5 MPa and 1.5 MPa confining stresses are summarized in (Fig. 14b,c). The τu1 values of different BS specimens under 0.5 MPa and 1.5 MPa exhibited the same trend as those observed under 1 MPa of confining stress. The best results were achieved for the τu1 of the M3 specimen. In addition, at 0.5 MPa of confining stress, τu1 decreased by 18.5%, 24.7%, and 35.8% for M3, M2, and M1, respectively, compared with that of the MC specimens. The τu1 values of W, T, and CJ decreased by 22.2, 34.6, 35.8, and 43.2%, respectively. Therefore, the best results were achieved for τu1 for the M specimens among all BS types.

Effect of the confining stress

Figure 15 summarizes the τu1-relative displacement relationship for the same BS specimens under various confining stresses. As the confining stress increased, the τu1 of the M2 specimens improved by 17.8% to 124.4%, and their residual strength increased by 100% to 316.7%. This trend was also observed in the specimens subjected to the other treatments, indicating that both τu1 and the residual strength improved with increasing confining stress. This enhancement is attributed to increased friction between the interfaces. However, the W and CJ specimens exhibited the opposite trend. For the CJ specimens, an increase in the confining stress from 0 MPa to 0.25 MPa resulted in only a 3.72% increase in τu1, which was considerably less than that observed in the other specimens. For the W specimens, τu1 actually decreased by 8.43% when the confining stress increased from 0.25 MPa to 0.5 MPa. This discrepancy is likely due to factors influencing the treatment effectiveness of the W and CJ methods, such as water pressure and interface delay time for the W method and operator skill and equipment for the CJ method. Consequently, the interface Rt achieved with these methods may not fully comply with regulations.

According to Table 1, the ratios Vcr/Vexp and Dexp/Dcr were both equal to 1 for most specimens, indicating that the confining stress had a minimal impact on ductility. In all the treatments, specimens with mold defects generally exhibited a ductility index greater than 1, with better ductility observed in the specimens subjected to higher confining stresses. This improved ductility is due to the compromised bottom surface of some key blocks in the defective M specimens. These defective blocks are more prone to shear failure than intact blocks. Consequently, the uneven force distribution among key blocks results in the initial crack forming on the BS, leading to the shear of all key blocks and the specimen reaching its τu.

The sliding friction coefficients for the interfaces with different treatments were calculated on the basis of the residual strength of the specimens. These coefficients decreased gradually with increasing confining stress due to the polishing effect. Table 5 summarizes the average dynamic friction coefficients (µd) for the interfaces under various confining stresses. Among all the treatments, the M3 and W specimens exhibited the highest friction coefficients, with values of 1.28 and 1.27, respectively.

Effect of the concrete strength

Figure 16 compares the τu values of the same BS specimen across different concrete strength classes. The average τu of the BS specimens increased by 6.5, 19.9, and 28.1% as the concrete strength class increased by 10 MPa, 20 MPa, and 30 MPa, respectively, indicating that τu increases with increasing concrete strength. This improvement is primarily attributed to the enhanced bond at the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the cement paste and the coarse aggregate in higher-strength concrete, which reduces the likelihood of interface debonding and microcracking in the paste. Previous studies have also shown that cracking in concrete typically initiates in the ITZ or the cement paste rather than propagating directly through the aggregate itself38. Therefore, ensuring both a dense ITZ and adequate aggregate quality is essential for maintaining the shear performance of bonding surfaces in high-strength concrete applications.

The sensitivity analysis and statistical validation

The sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis is conducted to assess the impact of three parameters—BS type, confining stress, and concrete strength—on the experimental shear carrying capacity (Vexp). Among these, BS type mainly differs in interface roughness, aside from variations in construction methods. Therefore, the BS type is represented by the roughness value for analysis, as shown in Table 4.

The steps for parameter sensitivity analysis include: First, a multiple linear regression model was used to calculate the regression coefficients (β) of each influencing parameter, and the model’s effectiveness was evaluated based on the coefficient of determination (R²) and p-values. Based on the regression results, the standard errors, t-statistics, and p-values of each independent variable were computed to determine their statistical significance (with p < 0.05 considered significant). Furthermore, standardized regression coefficients (β1) were calculated to directly compare the relative influence of each parameter on the dependent variable. Finally, the key parameters with the greatest influence on the dependent variable are identified through p-values, β1, and t-statistics. After fitting, the overall model shows a high goodness of fit, with an R² value of 0.91, indicating statistical significance (Fig. 17). Table 6 summarizes the regression coefficients, standard errors, t-statistics, and p-values for the three influencing parameters. Here, a p-value less than 0.05 indicates that the corresponding variable has a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable at the 95% confidence level.

The normal probability plot (Q-Q plot) of the residuals is shown in (Fig. 18). The Q–Q plot provides a graphical method to evaluate whether the residuals deviate from a normal distribution; when the points align with the reference line, the regression assumption of normality is considered valid. The residuals closely follow the reference line, suggesting approximate normality. This is confirmed by the Jarque-Bera test, which yields a p-value of 0.5. Since this p-value is much greater than 0.05, the null hypothesis that the residuals are normally distributed cannot be rejected, supporting the validity of the regression assumptions. Table 6 summarizes the specific analysis data for the three influencing parameters.

Based on Table 6, all three parameters individually show statistical significance (p < 0.05). However, a comparison of the β1 reveals substantial differences in their relative contributions. The roughness has a β of 34.2 (t = 8.57, p < 0.0001) with a β1 of 32.8. Concrete strength, while significant (β = 1.06, t = 2.95, p = 0.0051), has the smallest β1 of 0.09. In contrast, confining stress exhibits a significantly higher β of 144.1 (t = 18.1, p < 0.0001) and the largest β1 of 273.8.

These results clearly indicate that among the parameters studied, confining stress has the greatest impact on Vexp, followed by interface roughness (BS type) and concrete strength. While controlling confining stress is crucial for optimizing the shear carrying capacity of BS, in practice, interface pressure is determined by building use and structural type, making it difficult to control confining stress in structural engineering. In contrast, interface roughness is a controllable factor, making it particularly important to improve roughness compared to the other two factors.

Statistical validation

Table 6 also summarizes the confidence interval (CI) and coefficient of variation (CV) values. Based on Table 6; Fig. 19 presents the standardized regression coefficients (β₁) for each parameter along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (error bars), with p-values annotated to indicate statistical significance. The horizontal axis represents the values of β₁, while the horizontal error bars denote the CI, reflecting the uncertainty of the estimates. The p-values displayed on the right indicate the significance level of each parameter’s influence on Vexp.

The confidence interval analysis shows that the CI range for confining stress is [128.1, 160.1], with a width of 32, which is the widest among the three variables. However, considering its largest β, this width accounts for only 22.2% of the β, indicating high statistical significance. In contrast, the CI interval width for concrete strength is 141.5% of its β, indicating greater estimation uncertainty. This is further confirmed by the lower t-statistic (2.95) and higher p-value (0.0051) for concrete strength, suggesting weaker statistical significance. The CI for roughness ranges from [26.2, 42.3], with a width of 16.1, accounting for 47% of the β, indicating that its estimation precision falls between that of confining stress and concrete strength.

The CV analysis shows that the CV value for confining stress is the lowest (0.06), indicating that its contribution to the dependent variable is the most stable. The CV value for roughness is 0.12, indicating relatively low variability. In contrast, the CV value for concrete strength is the highest (0.34), suggesting that its effect is more susceptible to sample variation and model assumptions.

Overall, the analysis indicates that confining stress has the most stable and significant impact on the response variable, with roughness (BS type) also playing an important role at a moderate uncertainty level. However, the relatively high CV value and wider CI range for concrete strength suggest that further investigation is needed to confirm its impact on shear performance.

Calculation of the shear capacity (V u)

Equation fitting

Based on the results and analysis presented in Sect. 4, it is evident that during the initial loading stage, the interfaces of the specimens exhibited negligible relative displacement, with cracks appearing only at the specimen ends. Upon reaching the ultimate shear stress (τu), a sudden propagation of the main crack occurred at the interface, accompanied by an audible sound indicating interface failure. In the subsequent loading phase, specimens subjected to confining pressure exhibited a gradual increase in relative displacement, accompanied by the sound of aggregate interlock friction at the interface. These observations suggest that before reaching τu, cohesion at the interface played a dominant role in shear resistance. The moment τu was reached marked the complete loss of cohesion, with no remaining bonding effect at the interface. Beyond this point, shear resistance was primarily governed by aggregate interlock and friction. The load-displacement curves further indicate that while shear force could stabilize in the later stages due to friction, a decline in load-bearing capacity might occur as aggregate wear progressively reduced the interlock effect. An equation for calculating the interfacial τu of unconnected reinforcement BS (URBS) specimens was presented in Eq. 1 by Mohamad et al.39.

where c is the coefficient of cohesion of the concrete, fct is the axial tensile strength of the concrete, µs represents the coefficient of static friction between the interfaces, and σn is the normal stress between the interfaces.

The coefficients c and µs in Eq. 1 depend on the surface texture of the BS. These values were qualitatively evaluated by MC 2010 [11] and are presented in Table 7. The code classifies interfaces into four categories on the basis of the interface Rt, with critical Rt thresholds set at 3 mm for very rough surfaces and 1.5 mm for rough surfaces.

In this study, Rt was also used as a criterion for classifying interface types on the basis of the measured Rt results from Sect. 3.1.2. The selected Rt thresholds were 4 mm and 3 mm, leading to the classification of the interface types into three categories: (1) M3 and W interfaces with Rt greater than 4 mm were categorized as very rough. (2) M2, T, and M1 interfaces with Rt between 3 mm and 4 mm were categorized as rough. (3) CJ and PSP interfaces with Rt less than 3 mm were categorized as smooth.

According to Eq. 1, the values of c and µs for the different interface categories in this study were derived (see Table 8). The M3 and W BSs presented the highest coefficients, with c at 2.32 and µs at 0.97. In contrast, the gouge and indentation BSs had the lowest coefficients of friction and cohesion, with c at 1.8 and µs at 0.54. The values of c and µs used in this study are higher than those recommended by MC 2010, as the coefficients provided in the code tend to be conservative. Since the maximum Rt measured in this study exceeded the values specified in the code, the coefficients for M3 and the W BS, after thorough washing, were significantly higher than the code values.

Equation validation and comparison

The shear mechanisms are not uniformly addressed across different codes, leading to variations in the prediction equations. The equations provided in the codes (see Table 9) were used to estimate the shear capacity (Vu). The mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (COV) of the ratio of the calculated shear capacity (Vcal) to the experimental shear capacity (Vexp) are summarized in Table 10.

Among the codes listed in Table 9, JGJ 18, NZS310140, and ACI 318 − 1141 consider only the friction between the BSs. In contrast, other codes account for both bond strength and aggregate occlusion at the BS, with these factors incorporated into coefficient c. Notably, the ACI 318 − 11 code considers only reinforcement shear friction effects, making it unsuitable for predicting the shear capacity of URBS. NZS3101, built on ACI 318 − 11, includes the effects of confining stresses.

As shown in Table 10, the prediction results for JGJ 1 and NZS3101 are similar, with both yielding a COV of 53%. These codes provide the least accurate predictions, indicating that relying solely on friction leads to significant deviations between the Vcal and Vexp values. In contrast, MC 2010, BS EN 1992-1-142, and CSA A23.3-0443 incorporate cohesion between the BS in addition to friction. The mean values and COVs for Vcal/Vexp of these equations are 0.57, 0.53, and 0.21, with COVs of 23%, 31%, and 23%, respectively. Although these equations offer improved predictions, they remain conservative. The equation proposed in this study provides the best prediction results, with a mean value of Vcal/Vexp of 1.02 and a COV of 15%. This equation can be effectively used to calculate the Vu of URBS.

Finite element analysis

Finite element model

The specimens were modeled via ABAQUS. A truss element of T3D2 and a solid element of C3D8R were used to divide the reinforcement and concrete, respectively. The grid size of the reinforcement was 35 mm, and the grid size of the BS concrete was 20 × 20 × 19.5 mm. The boundary conditions and loading of the finite element models (FEMs) were consistent with those adopted in the test, as shown in (Fig. 20). The reinforcement was modeled via an ideal elastic‒plastic model36. The constitutive behavior of concrete was modeled using the concrete damaged plasticity (CDP) model in ABAQUS, which considers both compressive and tensile damage. Key parameters such as dilation angle, flow potential eccentricity, strength ratios, and viscosity were determined from the literature and calibrated against experimental results. Similar applications of the CDP model can be found in related study44.

The test results indicated that the failure modes of the specimens with different BS types were generally similar. The primary damage occurred due to the fracture of the BS, whereas the remaining concrete largely remained undamaged. To simulate the shear behavior and complete fracture between BSs, specific interactions were defined. The cohesion model was applied in both the tangential and normal directions. Additionally, penalized friction and hard contact were incorporated for the tangential and normal directions, respectively.

The cohesive principal constitutive curves are presented in Fig. 21. The values for the friction coefficients and tangential cohesion principal constitutive coefficients for various categories of BSs are summarized in Table 11, as detailed in Chaps. 3 and 4 of this study. The normal cohesion principal constitutive coefficients are based on reference45. According to reference45, the normal initial stiffness (kn) is set at 104 MPa/mm. The peak bond stress (tn0) normal to the interface and the normal fracture energy (Gcn) between the BSs are calculated via Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively. The maximum stress criterion was chosen as the damage initiation criterion for the cohesion model (see Eq. 4). It should be noted that the tangential peak stress values (ts0, tt0) in Table 11 are not fixed constants but are expressed as constitutive relations, depending on the average tensile strength of the interface concrete (ft), the confining stress (σ), and the static friction coefficient (µs). Since µs is governed by the roughness of the bonding surface, the interfaces were classified into three categories of roughness in this study, and corresponding formulas for ts0 were established. The main difference among these formulas lies in the value of µs, and the specific coefficients for each roughness type are listed in Table 11.

where tn0 is the peak bond stress normal to the interface, Rt is the interface roughness, and fcu is the cubic compressive strength of the concrete.

where Gcn is the energy absorbed during tensile failure of the interface and where fc is the axial compressive strength of the concrete.

where tn is the normal stress between the BS, tn0 is the normal peak bond stress, ts and tt are the tangential stresses between the BS, and ts0 and tt0 are the corresponding tangential peak stresses.

Validation of the finite element model

Load vs. relative displacement curve for BS

Figure 22 compares the test results with those from finite element analysis (FEA) for three categories of specimens, each subjected to identical confining stresses and having comparable concrete strength. The load‒relative displacement curves indicate that the FEA results closely align with the test data. However, the initial stiffness predicted by the FEA was slightly lower than that observed in the tests. This discrepancy arises because the initial stiffness in the FEA is based on the average stiffness derived from the secant at the peak of the test curve.

Table 12 Presents a comparison of the characteristic load values between the test results and FEA results. The deviation between the ultimate loads from the tests and FEA was within 24%. For specimens of the same category, the deviation in the average ultimate load was within 19%. These deviations confirm the reliability of the FEA results.

Stress fields

The failure modes of the specimens and the FEM were essentially the same. The failure mode of category 1, analyzed via the FEM, is shown in Fig. 23. The stresses were significantly greater at the top and sides of the FEM than in the other regions, which corresponded well with the distribution of tensile cracks that emerged on the top and sides of the specimens during loading.

The contact shear stresses along the Y direction on the BS are shown in Fig. 24. Before the shear stress reached τu, the shear stresses on the BS gradually decreased from the upper and lower ends toward the center as the relative displacement increased. With increasing load, the BS fractured when the shear stress reached τu. After fracture, with increasing relative displacement, the BS shear stress exhibited the same trend as before fracture. In addition, the stresses at the left and right edges of the BS showed a step change. The FEM stress distribution had the same trend as the crack distribution of the specimen throughout the test. Thus, the FEM can accurately simulate the failure mode of the URBS.

Given that the mechanical behavior of the Z-shaped shear specimen is predominantly controlled by the bonded interface, and that most of the influential factors are already reflected in the parameters of the proposed contact model, a broader parametric analysis was not pursued. This study focuses on evaluating the accuracy and applicability of the proposed interface model, providing a reliable simulation method for interface behavior in practical precast structures.

The FEA model adopted in this study is effective for simulating the macroscopic shear behavior of bonding surfaces; however, it cannot fully capture the fracture process and detailed failure patterns. These aspects can be more accurately represented by microscale models, as demonstrated in recent studies46,47.

The positive stress of category 1 (The image was generated using ABAQUS, version 2019, https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/). (a) X-direction positive stress of the FEM, (b) Y-direction positive stress of the FEM.

Y-direction shear stress variation of category 1 BS (The image was generated using ABAQUS, version 2019, https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/).

Conclusions

In this study, a novel frustum key block rough surface formed using a prefabricated mold was proposed to improve the shear performance of bonded interfaces (BSs) in precast concrete structures. The research aimed to address the limitations of traditional roughening methods by providing a standardized and efficient surface treatment technique. A series of quasi-static push-off tests were conducted to evaluate the shear performance of BSs with different surface types, confining stress levels, concrete strengths, key block sizes, and defect rates. Furthermore, a shear capacity prediction formula and a finite element simulation method were developed to support engineering applications. The major conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Failure characteristics: All specimens exhibited brittle failure. Specimens without confining stress experienced a sharp drop in load-carrying capacity after reaching the peak shear capacity (Vu), while those with confining stress retained residual strength due to friction along the interface.

-

(2)

Effect of surface type: The shear performance varied significantly among different BS types, reflecting the influence of interface roughness. The descending order of Vu was: M3 > W > M2 > T > M1 > CJ > PSP. The M3 specimen, with the largest frustum key blocks, exhibited the highest shear strength and reliability.

-

(3)

Influence of confining stress and concrete strength: Vu increased with both confining stress and concrete strength. Among M-type specimens, Vu improved with larger key block sizes and decreased with higher defect rates. Remarkably, even at a 70% defect rate, the M2 specimen outperformed the T, M1, CJ, and PSP specimens.

-

(4)

Quantitative trends: With increasing confining stress, Vu improved by 3.7 to 298.2%, while increasing concrete strength led to Vu improvements of 6.5 to 28.1%. For M specimens, increasing key block size enhanced Vu by 19.2 to 59.7%, whereas defect rates of 30 to 70% reduced Vu by 13.5 to 18.0%.

-

(5)

Verification and predictive modeling: The proposed finite element model accurately simulated the shear behavior of the BSs, validating the applicability of the interface constitutive model. The empirical formula developed in this study also provided reliable predictions of Vu for unreinforced bonded surfaces.

Overall, this study addressed the practical problem of interface preparation in precast structures by proposing a mold-based roughening method and verifying its mechanical effectiveness. The results contribute to a better understanding of shear performance mechanisms at bonded interfaces and provide analytical tools for structural design and simulation. This study still has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the finite element analysis cannot fully capture the fracture behavior and failure patterns of bonding surfaces, which could be more accurately represented using microscale models. Second, this study focused on bonding surfaces without connecting reinforcement, whereas the presence of interface reinforcement is expected to significantly alter the shear behavior of rough surfaces. These aspects should be further investigated in future work to provide a more comprehensive understanding of precast concrete bonding surface performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, H., Xu, C. & Du, X. Seismic response analysis of assembled monolithic subway station in the transverse direction. Eng. Struct. 219, 110970 (2020).

Englekirk, R. E. Design-construction of the Paramount-A 39-story precast prestressed concrete apartment Building. PCI J. 47 (4), 56–71 (2002).

Wu, E., Ayinde, O. O. & Zhou, G. Interface shear behaviour between precast and new concrete in composite concrete members: effect of grooved surface roughness. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 26 (6), 2799–2812 (2022).

Santos, P. M., D & Júlio E N B A state-of-the-art review on roughness quantification methods for concrete surfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 38, 912–923 (2013).

Hindo, K. R. In-place bond testing and surface Preparation of concrete. Concr. Int. 12 (4), 46–48 (1990).

Becker, M. E. Investigation of bond in unreinforced concrete interfaces for partial depth repairs and new construction. Univ. Tex. Austin. https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/14474 (2020).

Talbot, C. et al. Influence of surface Preparation on long-term bonding of shotcrete. Mater. J. 91 (6), 560–566 (1995).

JGJ1-2014. Technical Specification for Precast Concrete Structures (China Building Industry, 2014). (in Chinese).

Birkeland, P. W. & Birkeland, H. W. Connections in precast concrete construction. J. Proc. 63 (3), 345–368. (1966).

Mattock, A. H. & Hawkins, N. M. Shear transfer in reinforced concrete-Recent research. PCI J. 17 (2), 55–75 (1972).

MC. Model code for concrete structures 2010. Berlin: Ernst & Sohn, 2013. (2010).

Garbacz, A., Górka, M. & Courard, L. Effect of concrete surface treatment on adhesion in repair systems. Magazine Concrete Res. 57 (1), 49–60 (2005).

Santos, P. M. D. & Júlio E N B Factors affecting bond between new and old concrete. ACI Mater. J. 108 (4), 449 (2011).

Li, P. et al. Effect of concrete heterogeneity on interfacial bond behavior of externally bonded FRP-to-concrete joints. Constr. Build. Mater. 359, 129483 (2022).

Hofbeck, J. A., Ibrahim, I. O. & Mattock, A. H. Shear transfer in reinforced concrete. J. Proc. 66 (2), 119–128. (1969).

Hwang, S. J. & Lee, H. J. Analytical model for predicting shear strengths of exterior reinforced concrete beam-column joints for seismic resistance. ACI Struct. J. 96, 846–857 (1999).

Nabil, W. et al. Experimental and analytical study on the shear transfer in composite post tensioned precast concrete girders. Int. J. Civil Eng. 22 (1), 19–35 (2024).

Ceia, F. et al. Shear strength of recycled aggregate concrete to natural aggregate concrete interfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 109, 139–145 (2016).

Xiao, J., Xie, H. & Yang, Z. Shear transfer across a crack in recycled aggregate concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 42 (5), 700–709 (2012).

Haskett, M. et al. Evaluating the shear-friction resistance across sliding planes in concrete. Eng. Struct. 33 (4), 1357–1364 (2011).

Tassios, T. P. & Vintzēleou, E. N. Concrete-to-concrete friction. J. Struct. Eng. 113 (4), 832–849 (1987).

Wang, P., Ren, F. & Cai, M. Influence of joint geometry and roughness on the multiscale shear behaviour of fractured rock mass using particle flow code. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 1–14 (2020).

Kim, J., LaFave, J. M. & Song, J. Joint shear behaviour of reinforced concrete beam–column connections. Magazine Concrete Res. 61 (2), 119–132 (2009).

Choi, J. S. et al. Horizontal shear behavior of self-compacting lightweight concrete composite beams with dry joints and unbonded reinforcements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 152, 105687 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Full-scale Experimental Study on Shear Behavior of multiple-keyed Epoxy Joints in Precast Concrete Segmental bridges//Structures Vol. 45, 437–447 (Elsevier, 2022).

Kwon, T. H., Hong, E. S. & Cho, G. C. Shear behavior of rectangular-shaped asperities in rock joints. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 14, 323–332 (2010).

Feng, J. et al. Effect of joint width on shear behaviour of wet joints using reactive powder concrete with confining stress. Eng. Struct. 293, 116566 (2023).

Yuan, A. et al. Shear behavior of epoxy resin joints in precast concrete segmental bridges. J. Bridge Eng. 24 (4), 04019009 (2019).

Ayinde, O. O. et al. Influence of interface roughness geometrical parameters on the shear behaviour of old and new concrete interface. Asian J. Civil Eng. 23, 229–247 (2022).

ASTM C33/C33M-18. Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates (ASTM International, 2018).

14684 – 2011, G. B. T. Sand for Construction (China Standards, 2011). (in Chinese).

Yuan, A., Zhao, X. & Lu, R. Experimental investigation on shear performance of fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete dry joints. Eng. Struct. 223, 111159 (2020).

Mattock, A. H., Li, W. K. & Wang, T. C. Shear transfer in lightweight reinforced concrete. PCI J. 21 (1), 20–39 (1976).

DB 3401/T 254–. Technical specification for joint surface of monolithic precast concrete structure. Hefei market supervision and Administration Bureau. (in Chinese). https://std.samr.gov.cn/db/search/stdDBDetailed?id=ED7D8DFF04B4CDF4E05397BE0A0AE11B (2022).

Jiang, Q. et al. Rough bonding surface of precast concrete components. (2022).

GB 50010 – 2010. Code for Design of Concrete Structures (China Building Industry, 2015). (in Chinese).

GB/T 228.1–2021. Metallic materials—tensile Testing—part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature (China Standards, 2021). (in Chinese).

Zhu, Y. et al. Regularized density-driven damage mechanics model for failure analysis of cementitious composites. J. Eng. Mech. 150 (9), 04024064 (2024).

Mohamad, M. E. et al. Friction and cohesion coefficients of composite concrete-to-concrete bond. Cem. Concr. Compos. 56, 1–14 (2015).

NZS 3101 – 2006. Concrete Structures Standard (Standards New Zealand, 2006).

ACI 318 – 11. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary (American Concrete Institute, 2011).

BS EN Eurocode 2: design of concrete structures - part 1–1: general rules and rules for buildings. (London: BSI Standards Limited, 2004).

CSA A23.3-04. Design of Concrete Structures (CSA Group, 2004).

Zhu, Y. et al. Experimental and numerical study on the nonlinear performance of single-box multi-cell composite box-girder with corrugated steel webs under pure torsion. J. Constr. Steel Res. 168, 106005 (2020).

Zhou, J. Study on the Application Technology of Shear Walls with Precast Concrete Hollow Moulds (Tsinghua University, 2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. Coupled lattice discrete particle model for the simulation of water and chloride transport in cracked concrete members. Computer-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 40 (8), 982–1003 (2025).

Zhu, Y. et al. Multiscale lattice discrete particle modeling of steel-concrete composite column bases under pull-out and cyclic loading conditions Comput. Struct. 310, 107705 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The research in this paper was financially supported by the Xinjiang Key Laboratory of Hydraulic Engineering Security and Water Disasters Prevention (No. ZDSYS-YJS-2022-11), the Central Government-Guided Funds for Regional Science and Technology Development (No. ZYYD2024CG20), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52178472), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. JZ2023HGTB0257). Their support is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Y. wrote the main manuscript text, Q.J. oversaw the implementation of the research project, X.C. offered critical revisions and editing, Lk.Z. contributed to the literature review, Jq.H. performed statistical analysis, Yl.F. provided technical support. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, F., Jiang, Q., Chong, X. et al. Investigation of the shear performance of multi-key block bonding surfaces without connecting reinforcement for precast elements. Sci Rep 15, 40274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24057-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24057-w